Spectacularizing Parisian “Savages” during the Great Flood of 1910: How “les Apaches” Overshadowed the Cult of the Hero in les Quatre Grands

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Great Flood of January 1910 plunged the City of Light into darkness.[1] Every neighborhood had to evacuate some of its members and reckon with encroaching waters from the Seine pushing their way up through subterranean streams and pipes. Policemen and volunteers patrolled the streets in flat-bottom boats to guard vacant homes and businesses against looters. Volunteers from working-class neighborhoods were especially active in saving victims from flooded homes and rickety gangways. When the waters reached the Chamber, the heart of the Third Republic, on January 27, all normal government operations ceased and a martial government oversaw the needs of the city, calling in additional marines and sailors from the provinces.[2] Despite all odds, the flood response coordinated on the spot between the Third Republic, the military, and the majority of Parisians kept the death toll remarkably low for a modern disaster.[3] Yet, this story of resilience and heroism was not the dominant narrative that Parisians and the whole of France would read in the daily press.

By 1910, les quatre grands, or Le Matin, Le Journal, Le Petit Journal, and Le Petit Parisien, reigned at the center of political and cultural life in France. With a collective readership of over four million at a time when the country’s population crested at forty million, les quatre grands benefitted from the Third Republic’s broad educational reforms that raised literacy in France to a nearly universal level, making newspapers accessible to every adult.[4] The daily press maintained high circulations among different classes by keeping prices low and dramatizing everyday news through the language of spectacle.[5] The Great Flood of 1910 exemplifies this trajectory in the press, for the language of spectacle dramatized the disaster and gave both Parisians and the nation a way to understand the flood’s reality experientially.[6]

In the reporting on the flood, the difference between how les quatre grands positioned spectacular stories about “les apaches” and those about heroes shows a shift in the discourse towards the problem of urban crime and away from the cult of the hero. [7] In Belle-Époque France,[8] the term “les apaches” referred to juvenile “gangs” from working-class neighborhoods of Paris like Belleville, Montreuil, and Montmartre rather than the Apache Tribes of the American Southwest and Mexico.[9] Journalists borrowed the name from popular travel books and repurposed it to portray urban “savages” in Paris who rebelled against the factory clock, luxury, and the confines of a bourgeois lifestyle.[10] Since their first press appearance in 1900, the imagined “les apaches” were soon embellished with a brightly colored scarf, a worker’s vest or jacket, pointed toe boots, polished buttons, and a dagger at-the-ready to represent ongoing, violent crime in the city.[11] On the one hand, Le Matin, Le Journal, and Le Petit Parisien spectacularized “les apaches” as “savages” terrorizing the submerged city. On the other hand, Le Petit Journal foregrounded acts of heroism during the flood and forewent the rhetorical usage of “les apaches,” highlighting that “les apaches” were a cultural construction existing only in print. Since heroes of the flood and “les apaches” came from similar working-class backgrounds, this study argues that the rhetorical utility of the working-class functioned better for spectacularizing the “dangerous classes” that produced “les apaches” instead of individual heroes for the Third Republic.

Histories about the Great Flood intersect with the interdisciplinary study of disasters, for disasters and disaster responses are defined by cultural conceptions of society, politics, and nature.[12] As Christof Mauch argues, “it matters where a disaster occurs.”[13] Systematically examining reports on the Great Flood sheds light on how French men and women perceived crime, gender, and class in 1910. In particular, as Vanessa Schwartz argues for Fin-de-Siècle Paris, les quatre grands participated in the pursuit of urban spectacle, and reporting on the Great Flood shows a continuity of the language of spectacle between the Fin-de-Siècle and the Belle-Époque.[14] Yet, in Belle-Époque reporting, ominous depictions of “les apaches” overshadowed the “cult of the hero,” which Venita Datta argues characterized Fin-de-Siècle conceptions of national identify.[15] For this study of the flood, I consider how the emphasis on urban crime by working-class “apaches” shifted the discourse from national to local heroes. The first section examines the construction of “les apaches” in the daily press as threats to the public during the flood. The next section focuses on quantitative and qualitative analysis of reporting in les quatre grands on “les apaches” and “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” (hero/rescuer/rescue), which is followed by a consideration of the public debate about recognizing working-class heroes from the flood.

“Les apaches” were a social phenomenon anchored firmly in mass culture at the intersection of crime and perceptions of the working-class.[16] “Les apaches” first appeared in romans-feuilleton, serial novels published below the fold of the newspaper in the rez-de-chaussée, a section reserved for fictional writings.[17] The romans-feuilleton contributed to the success of les quatre grands by complimenting the dailies’ entertaining and informative articles.[18] For instance, travel journals like Déjà Chateaubriand’s Le voyage en Amérique of 1827 and Lafitau’s Moeurs des sauvages américains of 1845 appeared as romans-feuilleton and depicted the North American tribe of the Apaches as an emblem of inassimilable “savages.”[19] In contrast to the fictional narratives of the romans-feuilleton, the fait-divers sensationalized the ordinary by recounting true-crime stories and daily news on the top half of the newspaper.[20] Yet, the fait-divers and rez-de-chaussée were not ideologically static and borrowed melodramatic plot lines with a ready-made cast of heroes and villains, blurring the line between fact and fiction.[21] In 1900, “les apaches” appeared for the first time in the fait-divers in reference to violent working-class “gangs,” and the usage persisted.

By referring to Parisian “gangs” as “les apaches,” the French press drew on older discourse about barbarism’s resistance to civilization. Spectacularizing criminal stories incorporated everyday lootings, robberies, and violence into a new kind of public, urban life. Considered villains of modernity, “les apaches” resisted the movements of industrialization and urbanization, and represented “the disorganization of the frontier of urban life.”[22] Rather than conform to modern, orderly expectations of the working-class, young men and women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-one formed their own anti-society in “gangs” that preferred gaudy dress, smoking, argot (slang), and tattoos.[23] But this imaginary “apache” rarely existed in real life. Certainly, some young working-class men and women formed their own communities of solidarity as the last vagabonds of Haussmann’s great boulevards, which were designed to push the poor to the city’s margins.[24] Some “gangs” also adopted the term after the press popularized it, all claiming to be the “real” apaches.[25] Even then, groups identifying as “les apaches” never formed what the press represented as a unified, organized criminal network infiltrating the heart of Paris.[26]

In 1910, crime rates and violence declined in Paris, but concerns about crime persisted, populating newspapers with references to “les apaches.”[27] As social historian Gérard Jacquemet demonstrates, data of arrests and imprisonments from Parisian neighborhoods indicates a decrease in violent crime from 1869 to 1910, while the theft of food, wine, and goods purchased on credit increased, reflecting the impact of industrialization on the working-class.[28] This downshift in violent crime also correlated with police reforms under Prefect of Police Louis Lépine, who created the Mobile Brigade to monitor the streets.[29] Additionally, courts issued stricter punishments against violent crimes, such that a crime previously punishable by a couple of years in prison instead condemned people to forced labor by 1910.[30] The intensity of public concern about crime was reflected in how the daily press reported on the flood in Paris.

On January 20, while mudslides and rising waters upriver signaled impending trouble, Le Matin had two articles on its front page about “les apaches,” and none about the flooding upriver. In the first article titled “An Alarming Series of Events: Apache Soldiers are Multiplying,” the paper supported Senator Charles Humbert’s proposed legislation in the Chamber to prohibit ex-convicts from serving in the colonial or metropolitan army.[31] At present, the law allowed for ex-convicts to serve under the French flag for three years, after which their record would be cleared.[32] Undersecretary of the War Department M. Albert Sarraut opposed the proposed law and argued that excluding ex-convicts from the army would cripple army recruitment.[33] Yet the press portrayed ex-convicts as violent “apaches,” and articles titled “Apache Soldiers” explicitly made this connection. Moreover, on January 27, the same day that the floodwaters reached the Chamber and plunged the city into martial law, journalist Jacques Dhur echoed Humbert’s concerns in an opinion column on Le Journal’s front page. Dhur argues that “apache” soldiers would have greater access to guns than typical ruffians who purchased their guns from a local seller, and concluded that there must have been a more elegant solution to employing working-class convicts than giving them the means to threaten human lives on the streets in uniform.[34] These articles illuminate a persistent question about disorder in the French military and cities at a time when reforms and police expansion reduced crime.

Underneath Dhur’s article on January 20, Le Matin also published the final part of a series of reports on crime in Paris. An indicative, large illustration of two “apaches,” a male and a female, accompanied the high commissioner’s calls for more severe rulings and better law enforcement. The largest image on the front page, this illustration was meant to attract attention. Dressed in their iconic hats and pointed shoes, “les apaches” smirked over a miniature policeman, and above their heads, an ominous hand dug a knife into the sidewalk along which pedestrians traveled, their long shadows trailing behind them. The caption underneath the illustration read: “The number of apaches increases in Paris; the number of victims also; only that of policemen does not increase.”[35] Regardless of the reality of crime rates, the press reported that the police lacked the resources to curtail crime in the city.

The threat of “les apaches” ruling Paris proved empty during the Great Flood. The police patrolled the streets and saved flood victims so regularly and effectively that some of the trust between the public and military was restored after the divisive Dreyfus Affair.[36] Yet while crime occurred on a remarkably small-scale during the flood, there was a persistent emphasis on crime in the public consciousness. This shared fear was promoted by the way the fait-divers presented crime which, as Edward Berenson notes, was similar to the roman-feuilleton since both “gave readers an exaggerated sense of the prevalence of crime and of its potential danger to them.”[37] Instead of systemic violence, les quatre grands could only report on individual “apaches” or small groups of them as looters, thieves, or disturbers of the peace.[38] As early as January 22, Le Petit Parisien reported on “les apaches” of Saint-Cloud robbing vacant homes.[39] When the City of Light lost power during the flood, reports on “les apaches” grew more ominous. Le Journal commented that, when the electric streetlights failed at Vincennes on January 30, “public security is threatened by this brisk obscurity, because les apaches become masters of the street.”[40] Yet, in the same article, Le Journal clarified that the police and servicemen were surveying the flooded streets regularly and apprehended anyone who attempted entry without surveillance, showing that “les apaches” were not the true “masters of the street.” Rather, the press indiscriminately dubbed any apprehended person as an “apache.” Le Journal also published stories on “apaches” ranging from two men stealing a bag of beans to a store-owner on Riant Street in Saint-Denis who attributed his diminishing stock to “apache” thieves.[41] Consequently, exaggerating petty crimes and unchaperoned persons as examples of organized infiltration by “les apaches” served to undermine effective surveillance by police and servicemen.

In light of the absence of spectacular crimes, stories about “les apaches” read more like fiction with characters artfully assembled in a battle of wills. The French press focused on who “les apaches” were. In each report with one or more “apaches” taken into custody, the press carefully noted names, ages, occupations, or addresses. At the start of the flood, Le Journal reported on “les apaches” of Saint-Cloud and of Suresnes and their attack on two wine merchants and three policemen. The sensational story listed the name and age of each participant: Alexis Aupetit, 20 and head of the band; Tellier, 18 “The Hedgehog of Suresnes”; Gaston Giraudon, 16; François Lennet, 17; Lucien Ruellot, 17; Roger, 18.[42] In reports on another crime, Le Petit Parisien and Le Journal published the names, ages, and occupations of the culprits: a plumber, a painter, and a prostitute living in the same area of Montreuil.[43]

According to reports, these young adults warred against the police as much as against the difficulties of the urban disaster. As Le Journal conveyed, the public and the police perceived “les apaches” as the paragons of iniquity: adulterers, murderers, prevaricators, and parricides, hating the police, the bourgeoisie, and work, in that order.[44] The conflict between the police and “les apaches” added melodrama to daily reports from the martial government about city administration. On January 30, Le Matin’s feature story covered Prime Minister Aristide Briand’s insistence on rigorous surveillance of all evacuated buildings, promising the strictest punishments so that “all apaches attempting to enter these buildings for pillaging will be the targets of a rapid and severe repression.”[45] At Boulogne, Le Petit Parisien reported, the authorities had taken the threat of theft so seriously that “les apaches had better keep an open eye out.”[46] Like previous depictions in Le Matin’s reports on January 20, articles during the flood juxtaposed the police in uniform with criminals presented as “les apaches” in conflict with one another, which directly addressed public concerns about the Parisian police’s ability to control crime in the city.

During the flood, reported encounters between the police and perceived “apaches” were mild and easily resolved, sometimes with the release of “les apaches.” For instance, the police caught Marcel Léonardi, age 16, while robbing a factory and market in Saint-Denis with a group, but released him after he insisted that the group forced him to participate under threat.[47] Similarly, Le Journal claimed that an “apache” was denied access to a gangway built to help pedestrians traverse the flooded street, but was not apprehended.[48] On the same day, Jules Lambert, a twenty-year-old homeless man, interrupted the flow of traffic along a gangway and resisted authorities attempting to move him. Lambert was arrested and taken to the depot. This nondescript, anti-climactic story, however, appeared under the eye-catching title “Apache versus Soldiers.”[49] In these cases, fait-divers article titles like “The Suburbs: Submerged and Famished become the proxy of Apaches,” “Against the Pillaging Apaches,” and “The Apaches are Mingling” were often more interesting than the subject matter.[50] As a fixture of boulevard culture, the fait-divers focused on exceptional events that happened to ordinary people.[51] Therefore, the lack of spectacular crimes speaks to the success of the flood response and shows the lengths the press used to muster a semblance of dramatic danger.

The articles discussed so far feature male “apaches” acting counter to the demands of the disaster, and in contrast, articles about female “apaches” continued to fascinate the public even in the midst of tragedy.[52] As Ann-Louise Shapiro argues in her important work on female criminals of the Belle-Époque, reports on crimes committed by women captivated readers since female criminals countered gender norms, which were at the epicenter of changing law codes in the Third Republic.[53] For instance, on January 25, two women threatened M. Henri Mathieu, a fish merchant, for goods, and when he called for help, they brandished knives from their purses, attacked him, and escaped before help arrived. Although the police knew one of the women’s names as “Blondinette de la Chapelle” (Blonde One of the Chapel), it was unknown if these women truly affiliated with “les apaches.” Regardless, the paper still identified them as such and titled the article “Female Apaches.”[54]

During the flood, les quatre grands each reported on la Grande Marcelle, whose story ran alongside, but independent from, the disaster. Louise Delarue was the mistress of Liabeuf, who had killed a policeman named Deray just before the floodwaters reached Paris. The police brought her into custody and questioned her about Liabeuf’s whereabouts. After Delarue’s release, friends of Liabeuf who the press called “les apaches” of Beaubourg attacked her for potentially betraying Liabeuf.[55]

The series of reports lasted throughout the flood like a sensationalized crime novel of the fait-divers, and Le Journal and Le Petit Parisien included photos on their front pages. Le Journal dedicated its front page to “the Queen of the Apaches of Beaubourg” and had pictures of her sitting with the police and of her tattoos.[56] Le Petit Parisien described the “curious tattoos on her arms” as “a bracelet crossed by two swords and conventional signs that, one believes, serve to identify her with the group.”[57] Female “gang” members typically had tattoos with the names of their lovers or other gang-related symbols, but despite the permanency of a tattoo, allegiances could be brief, which shocked and fascinated bourgeois expectations about women.[58] Le Journal boldly claimed that Delarue was “an apache in all of its expectations,” signifying that her body bore the marks of violence: scabs, stab wounds, revolver scars, etc.[59] Unfortunately, such violence continued for Delarue. By the end of January, she went to the Hôtel-Dieu with knife injuries to her hands and chest, and each major daily reported on the continued violence to her person.[60]

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of reports on “les apaches” and those featuring heroes in les quatre grands further illustrates how members of the working-class were portrayed during the disaster. This study focuses on the number of times that “apache” or “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” appeared in article titles from January 20 to February 8, 1910, which correlate with the beginning of the flood upriver and the final day of the Seine’s slow return to its banks in Paris and Parisian suburbs. Article titles not only introduced the subject of the column and marketed the newspaper’s material to readers, but also shaped expectations about the column’s content. The front page and the Dernière Heure (Breaking News) sections were prime spots for articles that would interest audiences the most during the flood. The quantitative analysis of the four major French dailies accounts for the frequency that these words appeared in article titles and for their location within the paper’s organization. Qualitative analysis of the article titles will overlap with the evaluation of discourse on heroism. This data analysis illuminates how the French press spectacularized “les apaches” and underrepresented individual heroes as key figures in the unfolding disaster.

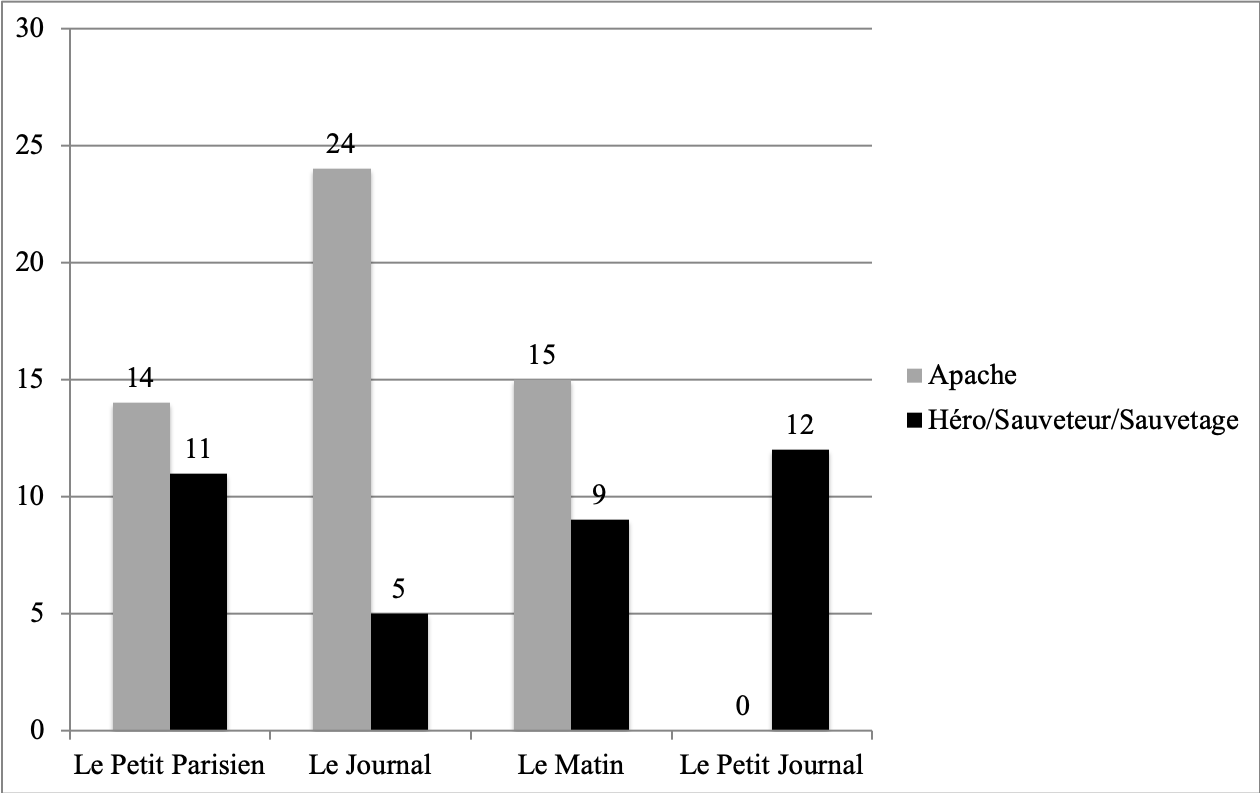

Table 1 illustrates the frequency of article titles with the eye-catching “apache” as compared to article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” for each of the major French dailies. Le Journal had the highest frequency of article titles with “apache,” at twenty-four total, which eclipsed the five article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” by 3.8 times. Le Matin also had a significant difference of 40% between fifteen titles with “apache” and nine titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage.” Le Petit Parisien had a difference of 21% between fourteen titles with “apache” and eleven titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage.” Le Petit Journal provides the foil for this study, because as previously mentioned in this article, Le Petit Journal alone did not use “apache” when describing either crime or the working-class. In consequence, there was a significant difference between the frequency of article titles with “apaches” and those with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” for two of the four major French dailies.

Though these titles named “apaches,” the articles themselves did not always report on “apache gangs” and their actions during the disaster, for in addition to reports on the flood, reports on Senator Charles Humbert’s proposed legislation continued but moved from the front-page to deeper within the daily papers. This legislation to prohibit ex-convicts from enlisting in the French army at home or abroad particularly mattered to Parisians since Paris’ police force was and is a branch of the military, and existing fears about a weak police force in Paris combined with worries about who the policemen could be. Consequently, a portion of the article titles with “apaches” in Le Petit Parisien, Le Journal, and Le Matin introduced reports on the legislation’s development in late January. For Le Petit Parisien, six of the fourteen articles with “apaches” in the title focused on the legislation, and of the six, four had the main heading of “Apaches in the Army.”[61] For Le Journal, nine of the twenty-four article titles with “apaches” relayed updates about the legislation.[62] Le Matin had twelve articles about the legislation with “apaches” in the title, and the remaining three articles with “apaches” in the title focused on crime before and during the flood.[63] The discrepancy between the

frequency of article titles with “apaches” that reported on legislative reform instead of the flood shows the political significance of the imagined social threat, and the rhetorical utility of casting ex-convicts as members of organized crime networks.

In contrast, article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” during these twenty days of reporting introduced content about rescues during the flood, the arrival or departure of additional help from the provinces, or the debate about how to recognize heroes of the flood. Out of its nine articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title, Le Matin had two articles about how to honor the heroes after the flood.[64] Le Journal published one article with “sauveteur” in the title about honoring heroes.[65] Le Petit Parisien had a higher frequency with four articles with “sauveteur” in the title addressing how to honor the rescuers.[66] Le Petit Journal had the highest frequency with six out of twelve articles with “sauveteur” or “sauvetage” in the title about the ways to honor rescuers.[67] Thus, among les quatre grands, 35% of all the articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title focused on how to honor the heroes nationally and locally.

Each of les quatre grands evidence a different rhetorical tendency when publishing article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” or “apache.” One way of identifying this tendency is by tracing the placement of these articles within each paper, which ranged from six to eight pages in length. The turning points of where articles would appear reflect developments in the disaster. Reports on the flood in Paris correlated with the Seine’s rising on January 23, and fears about public safety were heightened when the Third Republic was out of session from January 27-31 because of extreme flooding. Lastly, the discussion of hero commemorations continued until the Seine completely receded to its banks on February 8. Keeping these signposts in mind, the following section will consider each of les quatre grands in turn.

From January 20-23, Le Matin featured five stories about “les apaches” in the army on its front-page and its second page, with full columns of content.[68] By January 23, when the Seine began to rise considerably in Paris, reports about the flood began appearing on the front page of the paper, and the first story about a rescue appeared on January 25 when evacuations began.[69] Following this initial publication on the second page, seven articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title then appeared on either the first or second page. Only one of the nine articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title appeared on the third page, which was Le Matin’s Dernière Heure section for the most up-to-date news.[70] In consequence, articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title always appeared in the first sections of Le Matin. As the flood progressed, stories with “apache” in the title appeared less frequently on the cover page and none appeared on the second. Of the ten articles with “apache” in the title published after January 23, two appeared on the cover page: one warned of “apache” robberies while another gave an update on the ex-convict legislation.[71] Four articles with “apache” in the title appeared in Dernière Heure with updates about the ex-convict legislation and la Grande Marcelle. The remaining four articles appeared on the fifth and six pages alongside shorter articles about life in the city. For Le Matin, there was a clear shift to featuring reports on “héro” in the title, but articles with “apache” in the title returned to the front page and Dernière Heure when connected with the flood’s progression and threats to public safety.

In Le Petit Parisien, from January 20-25, articles with “apache” in the title appeared four out of eight times on the cover page, three of which focused on “apache” crimes.[72] Reports on the flooding began to appear on the cover page on January 23, and the first article with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title about the flood appeared on the second page on January 26.[73] The remaining articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title frequented the cover page three times,[74] the second page three times with other continued series from the cover,[75] the third page Dernière Heures twice,[76] and the fourth page once alongside shorter articles and stock market reports.[77] In contrast, after January 25, articles with “apache” in the title did not appear again on the cover page. Instead, an article with “apache” in the title appeared once on the second page about a conflict between an “apache” and a solider,[78] and the remaining three articles with “apache” in the title appeared on the fourth page.[79] Only one article with “apache” in the title appeared in Dernière Heure about an arrest of an “apache” solider.[80] Like Le Matin, Le Petit Parisien foregrounded articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title as articles with “apaches” in the title only reappearing if related to a social threat during the disaster. Both presses made this shift when the Seine’s flooding surpassed its annual water mark.

Le Journal problematizes this trend to shift articles with “apache” in the title to the back pages and move those with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” to the more prominent sections. The first article with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title appeared on January 29, and it is the only one to appear on the front page. Including the first, from January 29-February 1, at the height of the disaster, Le Journal published all of its five articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title: one on the cover page,[81] two on the second page that continued stories from the cover,[82] and two on the fourth page as the Dernière Heure.[83] Thus, Le Journal published stories about rescues at the most intense political moment when a martial government administered aid and security from January 27-31. On the other hand, articles with “apache” in the title appeared sixteen days out of this study of twenty days of reporting. The following lists the breakdown of the twenty-four articles with “apache” in the title: two appeared on the cover page;[84] one on the second page that continued stories from the cover;[85] eight on the third page alongside advertisements;[86] five on the fourth page Dernière Heure;[87] six on the fifth page;[88] one on the sixth page with shorter articles and Nouvelles Diverses;[89] and one on the seventh page with shorter articles and stock market reports.[90] The articles with “sauveteur” in the title appeared in Le Journal on four consecutive days, and in the same issues, those with “apaches” in the title appeared in the similar prominent locations. For instance, on January 29, the first article with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title appeared on the cover while, in the Dernière Heure section, an article with “apache” in the title filled two columns covering “apache” lootings.[91] While Le Matin and Le Petit Parisien placed articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title in the first portions of the paper, Le Journal privileged articles with “apache” in the title, which illustrates the stronger rhetorical utility of “apache” for this daily press.

Le Petit Journal reported on the flooding upriver as soon as January 20, and in the twenty days of daily reporting on the flood’s progression and effects, Le Petit Journal used the term “apache” only once. Buried in the text of an article and not in its title, the term “apache” was used to compare ex-convicts’ desire to remain near their hometowns to an “apache” who preferred to marry within her or his own social network.[92] The first article with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title appeared on January 25 on the cover page.[93] Of the remaining eleven articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title, only one appeared beyond the third page of Dernières Nouvelles.[94] The greatest concentration of articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title appeared from February 6-7, and these six articles celebrated the efforts of the rescuers, their departures, and local commemorations.[95] Of les quatre grands, Le Petit Journal featured the most articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title on the cover page with enough regularity to span the flood’s duration of extreme flooding from January 25-30 until its certain decline on February 6.[96]

In contrast to the other presses, since Le Petit Journal did not publish articles with “apache” in the title, its reporting of crime in the city situated looting and robberies into their particular contexts and thereby untied them from a coalescing theme of universal urban crime. When Le Petit Journal reported on la Grande Marcelle and her lover Liabeuf, they were not named as “apaches.”[97] When Le Petit Journal referred to the legislation for army recruits, their reporters referred to “Les condamnés de droit commun” (convicts of common law) rather than “les apaches.”[98] Reports exclusively referred to “thieves” rather than attributing all robberies to “apache gangs.”[99] This reporting style suggested that crime and violence during the flood were not a part of organized crime.

Overall, while the rhetorical utility of “apache” was to spectacularize articles about alleged crimes during the flood or legislation about army recruitment, articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” appeared with greater frequency in the most prominent sections of the paper after the Seine eclipsed its usual winter flood mark. Le Journal is the exception since it continued privileging articles with “apache” in the title throughout the disaster. After the flood’s conclusion, article titles with “apache” resumed their placements in Le Matin, Le Petit Parisien, and Le Journal, and Le Petit Journal continued forgoing this rhetorical usage and rather reported on crime in specific contexts.

Though les quatre grands resumed prior rhetorical usage after the flood, reporting on the Great Flood suspended the discourse of heroism and the spectacularization of “les apaches” in tandem, shedding light on evolving attitudes towards the urban working-class as potential heroes for the nation. In contrast to the specificity and fanfare dedicated to perceived “apaches” like la Grande Marcelle, article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” rarely even supplied the name of the hero. Out of eleven articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title, Le Petit Journal named only two specific heroes.[100] Le Matin had two out of nine article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” about specific rescuers.[101] Le Journal had one out of five article titles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” about a specific rescuer,[102] and Le Petit Parisien named two heroes in two out of eleven articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title.[103] Among les quatre grands, the remaining thirty articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title grouped rescuers together as a faceless collective, without names or ages. In an article titled “Braves Gens!” (Brave Men!), street-reporter Paul Lagardée uniquely listed the names and occupations of thirty-six heroes in Le Petit Parisien on February 6. From grocers who maintained operations to volunteers who guided barges, from day laborers who constructed gangways to soldiers who plunged into the icy waters and carried hundreds of people to safety, Lagardée precisely and thoroughly identified individuals who gave of themselves to help others during the disaster.[104] Lagardée’s reporting demonstrates that it was possible to identify many heroes of the flood, but the overriding majority of reporting in articles with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title focused more on heroic actions rather than the actors.

By focusing on heroic actions, les quatre grands folded the individual into conceptions of the nation, which blurred the fact that heroes and “apaches” came from similar working-class backgrounds. Marines and soldiers figured prominently in les quatre grands as heroes of the flood as seen in reports on how to honor their service to the public and Lagardée’s list of heroes.[105] But since marines and soldiers operated as a branch of the Third Republic, les quatre grands cloaked individual heroic acts in a rhetoric of duty. As Le Matin published on February 6, “All Paris valiantly did their part. One cannot cite the names of modest heroes, who during the common plight, gave their all: there are too many. One must credit them as one, by corporation.”[106] Consequently, unlike “les apaches,” heroes were primarily recognized in corporation even when there was opportunity to single out individuals for acts of courage.

When the press recognized an individual hero from the flood, then the story focused on the man’s modesty and nationalism rather than his individuality and motivation.[107] This rhetorical trend is best exemplified in Le Matin’s published interview with Emile Courboin, a soldier who oversaw the management of the Marne, a tributary of the Seine. Courboin raised the first alarm that the Seine’s tributaries were quickly becoming dangerous. Night and day, he monitored the progression of the river’s rise and often worked in the freezing water for hours to help. He remained at his post and kept the telegraph and telephone lines operable. When the reporter called him a hero for these actions, Courboin reportedly declined the title with a smirk and said he was no more than “a conscientious government worker;” when the paper asked if they could take his portrait for the paper, he agreed only reluctantly and added, “If you would like to publish the portrait of all those who did their duty and even more, the pages of your journal will not hold all of them.” This story’s parallel structure read like literature. The question “A hero?” opened each paragraph to emphasize that, although Courboin would not claim the title, he fulfilled every requirement for it.[108] In this sense, the press promoted a view of a hero who declined the title in lieu of his duty to the nation.

While only Le Matin published Courboin’s words, les quatre grands all portrayed the tragic death of Corporal Tripier as a sacrifice for the nation.[109] Corporal Tripier of the 7th company of the 5th infantry regiment drowned at the Quai Debilly on January 28 while helping a flood victim board a barge with another soldier. In a moment of confusion, the barge tipped, plunging all three into the water. Tripier was the only one to drown in the swirling currents, and reportedly the only rescuer to die during the flood. When his body was recovered, Prefect of Police Lépine requested that the city pay for the burial to honor his untimely death.[110] Tripier’s story appeared on the front page of Le Journal and Le Petit Journal with his portrait and that of the other soldier. Other than the occasional portrait, no details about Tripier’s life accompanied his story; family, hometown, place of residence, age, and any personal details were excluded. While the press celebrated Tripier’s sacrifice, he was not awarded any medal for courage or virtue posthumously, and his fame only lasted as long as the flood. Instead, the press essentialized him as a servant to the nation, which supported national narratives of duty and solidarity. Consequently, Tripier’s story was absorbed into a larger, unequivocal expectation of duty to the nation.

In contrast to the articles that spectacularized legislation to address the threat of “les apaches” in the army, each of les quatre grands reported on legislation for the rescuers by echoing the Third Republic’s rhetoric of duty and publicizing efforts in Paris to honor local instead of national heroes.[111] On January 31, at the beginning of the Chamber’s reopening session, Deputy of Paris M. Maurice Binder proposed extending a special promotion of the Legion of Honor to the military and civil rescuers whose courage particularly distinguished their labors during the flood.[112] The dossier for the Legion of Honor typically required a year to compile and process, but the new legislation would expedite the process and create a permanent promotion to the Legion of Honor for acts of courage and devotion during a natural disaster. President of the Council M. Briand, however, undercut this legislative change with a firm resolution that “there is no need for a stimulant of this nature to encourage citizens to do their duty.”[113] The matter was resolved with financial restitution and eight days of leave to recuperate. Consequently, in 1910, there were only two instances of national medals of honor given to those who participated in the flood response in conjunction with records of previous service.[114] The Third Republic folded individual heroes into its rhetoric of nationalism and duty, which effectively excluded the working-class from national awards for honor.

Yet Le Journal and Le Petit Journal published opinion pieces that countered the Third Republic’s decision and proposed honoring heroes as a way of reducing the focus on “les apaches” and crime in Paris. Le Journal’s Échos section specifically recorded the thoughts and impressions of the public, and on February 6, Échos reported that many of Le Journal’s readers found the government’s financial restitution insufficient for the policemen and soldiers who demonstrated such valor during the disaster, asking:

And why would one not prepare a celebration in their honor, a celebration not overly joyful but ample and dignified, like the military banquets for the Grand Army that Emperor Napoléon and the City of Paris organized at the Palais-Royal? Is it not fitting to celebrate a victory, a harsh and difficult victory over an enemy multiple and terrible, insatiable and furiously resurgent?[115]

Jean Lecoq, an opinion writer for the Le Petit Journal who wrote 256 articles in 1910, made a similar proposition. He proposed creating announcement boards in each neighborhood to list the virtuous and courageous acts of the neighborhood’s residents, thereby providing examples for emulation and a moral recompense for the heroes. Even if their names could not be identified, Lecoq argued that heroic acts should be publicly recognized and honored so as to reduce the public’s focus on crime, for as he wrote, “crime preoccupies us too much... way too much; in any case, much more than virtue.” Lecoq added that criminal reports so preoccupied the papers and the government that one would believe there were more “apaches” in France than virtuous citizens. Lecoq proposed a systemic change that would foreground brave acts of rescuers and heroes of the flood, no matter their class or origin.[116]

Each of les quatre grands also reported on local commemorations of the rescuers, for although the Third Republic overlooked the flood’s heroes, the people of Paris honored them locally. Music halls, theaters, and restaurants honored “these modest and unwavering heroes.”[117] Société nationale de sauvetage (National Society of Rescue) organized local members to help in the flood and wrote their names in a golden book.[118] La Société des sauveteurs de la Seine (Society of Rescuers of the Seine) met on January 30 to vote on honoring a rescuer who died.[119] On February 7, La Fédération des sociétés de natation et de sauvetage (Federation of Swimming and Rescue Societies) and La Société nationale d’encouragement à la natation (National Society for the Encouragement of Swimming) met at the Sorbonne’s Grand Amphitheater for their annual celebration of civic courage and extended financial awards to scholarly, military, and private groups connected with the flood relief. [120] But these celebrations had their limits, for the marines and soldiers who many believed deserved the greatest recognition could not attend celebrations in their honor once they returned to their respective stations throughout France.[121] The cult of the hero, therefore, still operated at the local level during the Great Flood despite a lack of avenues to recognize individual, national heroes, and les quatre grands participated in the capacity as the local papers of Paris, the epicenter of France.

Reporting on the Great Flood revealed a new attitude in les quatre grands towards the working-class. First imagined in 1900, “les apaches” symbolized by 1910 the unresolved question of urban crime in Paris, and the term’s rhetorical utility was to spectacularize quotidian crimes and legislation, depicting the city as under threat by organized crime networks. Reporting during the flood demonstrated a tenacity by Le Journal, Le Matin, and Le Petit Parisien to maintain articles with “apache” in the title even as reports on the flood and its heroes crowded the major pages. In all les quatre grands, reporting on heroes marked a turn away from the cult of the hero towards a rhetoric of duty and collective action for the nation, contrasting reports on the local Parisian culture that celebrated the individual. The difference between reporting on heroes and “les apaches” during the Great Flood emphasizes the continuity of urban spectacle and the intentional but contested shift to the corporation of heroes in the years before the Great War.

I would like to thank Margaret Andersen, Jeffrey Jackson, Bethany Keenan, and the anonymous Journal of the Western Society for French History reviewers for helpful comments on this article.

One headline of Le Petit Parisien was: “Une catastrophe sans exemple: La Capitale est envahie: La plupart des services publics sont actuellement suspendus: Le gouvernement militaire de Paris a pris des dispositions pour que l’armée puisse secourir utilement la population en danger,” Le Petit Parisien, January 27, 1910.

While the Third Republic claimed that no one died during the flood, the French press reported on roughly twenty deaths among flood victims and rescuers. Jeffrey Jackson writes that insufficient records of death inhibit an accurate account of how many perished directly or belatedly because of the flood. Jeffrey Jackson, Paris Under Water: How the City of Light Survived the Great Flood of 1910 (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 174-176.

Edward Berenson, The Trial of Madame Caillaux (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992), 209.

As described by Benedict Anderson, newspaper coverage is particularly useful in understanding the formation of the nation. I use Anderson’s definition of the nation as “an imagined political community” that is both limited and sovereign, creating a common sense of identity among people who would never meet. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1991), 5-6, 25-26.

I maintain the French usage of “les apaches” in this article since it refers uniquely to both real and imagined ruffians from the working-class Parisian, criminal underworld. In French, the noun “les peaux-rouges” is used to identify the indigenous peoples, languages, and cultures specific to North America, some of whom identify as “Apache”.

I agree with Eugen Weber that the Belle-Époque had a distinct mode from that of the nineteenth century vis-à-vis nationalism and social anxieties, so I distinguish between the Fin-de-Siècle as the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the Belle-Époque as 1900-1914. Eugen Weber, France: Fin-de-Siècle (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1986), 2.

Gérard Jacquemet, “Belleville ouvrier à la Belle Époque,” Le Mouvement social no. 118 (January-March, 1982): 77.

Michelle Perrot, “Dans le Paris de la Belle Époque, les “Apaches”, premières bandes de jeunes,” La lettre de l’enfance et de l’adolescence no. 67 (2007): 73.

The iconic sketch of an “apache” from Le Petit Journal best illustrates this imagined figure. I thank the anonymous Journal of the Western Society for French History reviewer who contributed to clarifying my description of the “apache” image. “L’Apache est la plaie de Paris,” Le Petit Journal, 20 October 1907.

In one of the few works dedicated solely to the flood, Jeffrey Jackson argues that Parisians’ solidarity against the invading waters served as the linchpin between their unity in the Franco-Prussian War and their resiliency during World War I. Caroline Ford’s chapter “The Torrents of the Nineteenth Century” uses the Great Flood of 1910 as an example of how floods continued to shape France’s national environmental consciousness in the twentieth century. Disaster scholars like Rebecca Solnit and Chistof Mauch postulate that disasters change depending on the culture of a place, its politics, and its social structure, for a disaster or catastrophe is defined in relation to the perception of its impact on humans. Jackson, Paris Under Water, 100-106, 223; Caroline Ford, Natural Interests: The Contest over Environment in Modern France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 89-90; Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster (New York: Penguin Group, 2009), 15; Christof Mauch, “Introduction” in Natural Disasters, Cultural Responses: Case Studies toward a Global Environmental History, ed. Christof Mauch and Christian Pfister (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009), 4-9.

Schwartz shows that the press forcefully constituted a collective and then intended to entertain it through reading chiefly about the urban experience. Vanessa Schwartz, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998), 27.

Datta further elucidates that les quatre grands in the Fin-de-Siècle promoted national solidarity by celebrating French grandeur. Thus “the cult of the hero” framed reporting on disasters like the Bazar de la Charité Fire of 1897. Newspapers fêted working-class heroes and condemned cowardly bourgeois men from the fire according to the press’ moral and political judgments of the disaster. Venita Datta, Heroes and Legends of Fin-de-Siècle France: Gender, Politics, and National Identity (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 1, 35-37, 44-45.

Perrot, “Dans le Paris de la Belle Époque,” 72. For more detailed history of this phenomenon’s development, see Dominique Kalifa, “Archéologie de l’Apachisme. Les représentations des Peaux-Rouges dans la France du XIXe siècle,” Revue d’histoire de l’enfance « irrégulière » no. 4 (2002); Dominique Kalifa, Les bas-fonds : Histoire d’un imaginaire (Paris : Éditions du Seuil, 2013); Dominique Kalifa and Jean-Claude Farcy, Atlas du crime à Paris (Paris : Parigramme, 2015).

Berenson, The Trial of Madame Caillaux, 217; Maria Adamowicz-Hariasz, “From Opinion to Information: The Roman-Feuilleton and the Transformation of the Nineteenth-Century French Press,” in Making the News: Modernity and the Mass Press in Nineteenth-Century France, ed. Dean de la Motte and Jeannene M. Przyblyski (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999),160.

John Merriman, The Margins of City Life: Explorations on the French Urban Frontier, 1815-1851 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 81.

Dominique Kalifa, “Crime Scenes: Criminal Topography and Social Imaginary in Nineteenth-Century Paris,” French Historical Studies 27, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 191-193.

Social historian Gérard Jacquemet also shows that Belleville–where the first group of “apaches” formed–was not in fact any more violent than other neighborhoods in Paris. Gérard Jacquemet, “Belleville ouvrier à la Belle Époque,” Le Mouvement social no. 118 (January-March, 1982): 77.

Luc de Vos, L’Intermédiaire des Chercheurs et Curieux, Volume 49 (20 March 1904), 449.

Humbert represented the Department of the Meuse and was also an army captain. “Une inquiétante série: les soldats apaches se multiplient,” Le Matin, January 20, 1910.

“Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Petit Parisien, January 29, 1910.

“Les apaches hors de l’armée: ‘Une loi prochaine assainira nos régiments’ nous a déclaré M. Sarraut,” Le Journal, January 23, 1910.

Jacques Dhur, “Le Commerce des Armes doit être réglementé,” Le Journal, January 27, 1910.

“Un haut fonctionnaire de la police explique la recrudescence du crime,” Le Matin, January 20, 1910.

As disaster scholars show, looting after disaster is a controversial matter. It is often assumed as a “natural” consequence of a destabilizing disaster, which E.L. Quarantelli calls the “myth of looting.” E.L. Quarantelli, “The Myth and the Realities: Keeping the ‘Looting’ Myth in Perspective,” Natural Hazards Observer 31, n. 4 (March 2007), 3.

“La terreur à Saint-Cloud: Une bande d’apaches saccage un débit. Le patron et deux agents sont blessés,” Le Petit Parisien, January 22, 1910.

“En banlieue. Les apaches s’en mêlent,” Le Journal, January 30, 1910.

“Toujours les apaches,” Le Journal, January 31, 1910; “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Journal, February 4, 1910; “Le revolver de l’apache,” Le Journal, February 4, 1910; “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Journal, February 5, 1910.

“La terreur en banlieue: Des apaches assomment à Suresnes et à Saint-Cloud deux marchandes de vins et blessent trois agents,” Le Journal, January 22, 1910.

“La Maîtresse de Liabeauf lardée de coups de couteau,” Le Petit Parisien, January 31, 1910; “La Grande Marcelle assaillie à coups de couteau,” Le Journal, January 31, 1910.

“Échos,” Le Journal, February 6, 1910; Perrot, “Dans le Paris de la Belle Époque,” 74.

“La détresse en banlieue. À Boulogne,” Le Petit Parisien, February 1, 1910.

“La banlieue submergée et affamée devient la proie des apaches,” Le Journal, January 29, 1910; “Contre les apaches pillards;” “Les apaches s’en mêlent!” Le Petit Parisien, January 25, 1910.

Perrot, “Dans le Paris de la Belle Époque,” 74; Daniel-Frédéric Lebon, “Béla Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and the Apaches from Paris,” Studia Musicologica 53, no. 1/3 (March 2012): 233, 240

Gay Gullickson also identifies a longer history of this fascination during the Paris Commune when les pétroleuses (female incendiaries) represented a world turned upside down. Ann-Louise Shapiro, ““Stories More Terrifying than the Truth Itself”: Narratives of Female Criminality in Fin-de-Siècle Paris,” in Gender and Crime in Modern Europe, ed. Margaret L. Arnot and Cornelie Usborne (London: University College London press, 1999), 218; Gay Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 12.

“Les amies de Liabeuf. Arrestation de la Grande Marcelle,” Le Journal, January 21, 1910; “La maîtresse de Liabeuf est arrêtée,” Le Matin, January 21, 1910; “Émule de Liabeuf,” Le Petit Journal, January 22, 1910. “L’affaire Liabeuf: La maîtresse du terrible apache a été interrogée, hier par le juge d’instruction. Elle nie lui avoir attaché ses ‘brassards,’” Le Petit Parisien, January 23, 1910.

“L’affaire Liabeuf. La maîtresse du terrible apache a été interrogée, hier, par le juge d’instruction. Elle nie lui avoir attaché ses ‘brassards.’”

“La Grande Marcelle en libérte,” Le Journal, January 30, 1910; “La maîtresse de Liabeuf lardée de coups de couteau;” “La ‘Grande Marcelle’ poignardée,” Le Matin, January 31, 1910; “La “Grande Marcelle,” l’amie de Liabeuf, blessée de quatre coups de couteau,” Le Petit Journal, January 31, 1910.

“Les apaches dans l’armée: Une proposition de loi de M. Charles Humbert,” Le Petit Parisien, January 21, 1910; “Les soldats apaches,” Le Petit Parisien, January 21, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée: Le gouvernement s’émeut,” Le Petit Parisien, January 23, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée: Mesures de protection: Le Rapport de M. Raiberti,” Le Petit Parisien, January 24, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée;” “Le cuirassier apache a été arrêté hier,” Le Petit Parisien, February 8, 1910.

“Les apaches dans l’armée: Une proposition de loi de M. Charles Humbert;” “Les soldats apaches,” Le Journal, January 21, 1910; “Les soldats apaches,” Le Journal, January 22, 1910; “Les apaches hors de l’armée: ‘Une loi prochaine assainira nos régiments’ nous a déclaré M. Sarraut;” “La Commission de l’Armée: Les retraites proportionnelles: Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Journal, January 23, 1910; “Le projet du gouvernement sur les apaches de l’armée,” Le Journal, January 24, 1910; “Les soldats apaches,” Le Journal, January 27, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Journal, January 29, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Journal, February 5, 1910.

“Une inquiétante série: Les soldats apaches se multiplient,” Le Matin, January 20, 1910; “Les soldats apaches,” Le Matin, January 20, 1910; “Cambrioleurs assassins: ‘Les apaches qui déshonorent l’armée les ont pervertis’ dit le président,” Le Matin, January 21, 1910; “La fin des apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 22, 1910; “La fin des apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 23, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 27, 1910; “La vie militaire: Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 29, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 30, 1910; “Le soldat apache,” Le Matin, January 31, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, February 5, 1910; “Soldats apaches,” Le Matin, February 6, 1910; “Cuirassiers apaches,” Le Matin, February 8, 1910.

“La Chambre des deputes rend un homage solennel aux sauveteurs,” Le Matin January 28, 1910; “Des Croix pour les sauveteurs,” Le Matin, January 31, 1910.

“Au Conseil Municipal: On a loué les sauveteurs et envisage les mesures d’hygiène à prendre pour éviter les épidémies,” Le Petit Parisien, January 31, 1910; “Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, January 31, 1910; “Au Palais-Bourbon: Des décorations pour les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, February 1, 1910; “La Fédération des sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, February 7, 1910.

“Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, January 29, 1910; “La revue des sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, February 6, 1910; “Les officiers sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, February 6, 1910; “Hommage aux sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, February 6, 1910; “Éloges aux marins sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, February 7, 1910; “La fête de la natation et du sauvetage à la Sorbonne,” Le Petit Journal, February 7, 1910.

“Une inquiétante série: Les soldats apaches se multiplient;” “Le nombre des apaches augmente à Paris,” Le Matin, January 20, 1910; “Cambrioleurs Assassins;” “La fin des apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 22, 1910; “La fin des apaches dans l’armée,” Le Matin, January 23, 1910.

"Le sans-fil sauveteur: Un steamer appelle au secours," Le Matin, February 5, 1910.

"La banlieue aux apaches," Le Petit Parisien, January 20, 1910; "La terreur à Saint-Cloud;” "Les apaches dans l'armée,” Le Petit Parisien, January 23, 1910; “Les apaches s'en mêlent!”

In this study, the first article that appeared in the sample with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title was on January 20, 1910 in reference to an accident on Rue de l’Ermitage. Thus, the first article with “héro/sauveteur/sauvetage” in the title about the flood was on January 26. “Un héros anonyme,” Le Petit Parisien, January 26, 1910.

“Du Palais-Bourbon à Javel: C’est l’affolement et la misère: Des mères implorent, des enfants pleurent, des sauveteurs exposent leur vie,” Le Petit Parisien, January 29, 1910; “Au Palais-Bourbon: Des décorations pour les sauveteurs;” “Les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, February 6, 1910.

“Héroïsme et misère,” Le Petit Parisien, January 28, 1910; “Au Conseil Municipal;” “Un sauveteur blesse,” February 1, 1910.

“Un hussard sauveteur félicité par son colonel,” Le Petit Parisien, February 5, 1910; “La fédération des sauveteurs.”

“Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Petit Parisien, January 29, 1910; “Deux apaches parisiens arrêtés à Bruxelles,” Le Petit Parisien, February 2, 1910; “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Petit Parisien, February 8, 1910.

“Une digue se rompt: Sauveteur noyé,” Le Journal, January 29, 1910.

“Emouvant sauvetage,” Le Journal, January 31, 1910; “Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Journal, February 1, 1910.

“Arrivée de sauveteurs,” Le Journal, January 30, 1910; “Un sauvetage à Puteaux,” Le Journal, January 31, 1910.

“Les apaches dans l’armée: Une proposition de loi de M. Charles Humbert;” “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Journal, January 23, 1910; “Le projet du gouvernement sur les apaches de l’armée;” “Les soldats apaches,” Le Journal, January 27, 1910; “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Journal, January 29, 1910; “Exploits d’apaches,” Le Journal, February 1, 1910; “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Journal, February 3, 1910; “Le revolver de l’apache,” Le Journal, February 3, 1910.

“Les soldats apaches,” Le Journal, January 22, 1910; “La banlieue submergée et affamée devient la proie des apaches;” “Les apaches s’en mêlent;” “Apaches contre soldats;” “Les apaches dans l’armée,” Le Journal, February 5, 1910.

“Éventre par un apache,” Le Journal, January 21, 1910; “La Commission de l’Armée; “Entre agents et apaches,” Le Journal, January 25, 1910; “Les apaches de Pantia,” Le Journal, January 26, 1910; “Les apaches en banlieue,” Le Journal, February 4, 1910; “Le crime du Boulevard Voltaire: Une femme apache aux assisses,” Le Journal, February 8, 1910.

“Une digue se rompt: Sauveteur noyé;” "La banlieue submergée."

“Les Condamnés de Droit commun dans l’armée. Le projet du gouvernement,” Le Petit Journal, January 23, 1910.

“Un sauvetage en Radeau à Choisy-Le-Roi,” Le Petit Journal, January 25, 1910.

“Le départ de sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, February 6, 1910; “La revue des sauveteurs;” “Les officiers sauveteurs;” “Hommage aux sauveteurs;” “Éloges aux marins sauveteurs;” “La fête de la natation et du sauvetage à la Sorbonne.”

“Un sauvetage en Radeau à Choisy-Le-Roi;” “Les progrès du désastre: Un caporal, employé au sauvetage, s'est noyé quai Debilly,” Le Petit Journal, January 29, 1910; “Ça et là: Un jeune homme entrainé mais sauvé,” Le Petit Journal, January 30, 1910; “Le départ de sauveteurs.”

“Á travers Paris. Émule de Liabeuf,” Le Petit Journal, January 22, 1910.

“En Seine-et-Oise: A. Corbiel, Le sous-préfet sauveteur,” Le Petit Journal, January 27, 1910; “Les progrès du désastre.”

“Le sans-fil sauveteur; “Le héros de Chalifert,” Le Matin, February 6, 1910.

“Un sauveteur blessé;” “Un hussard sauveteur félicité par son colonel.”

Paul Lagardée, “Les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, February 6, 1910.

Paul Lagardée, “Les sauveteurs;” “Échos;” “Sous l'eau: Toute la plaine, en aval de Paris, n'est qu'un immense lac, où les sauveteurs se prodiguent sans réserve,” Le Matin, February 2, 1910; “Les braves soldats,” Le Matin, February 4, 1910; “Le départ de sauveteurs.”

“Une victime de devoir: Comment le caporal Tripier se noya, hier, quai Debilly, en accomplissant son service. Son cadavre n’a pas encore été retrouvé,” Le Petit Parisien, January 29, 1910; “Les progrès du désastre;” “Les nouvelles conquêtes du fleuve,” Le Matin, January 29, 1910; “On retrouve le corps du caporal Tripier,” Le Journal, February 2, 1910.

“Éloge aux sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, January 31, 1910.

“Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, January 31, 1910; “Des Croix pour les sauveteurs;” “À la Chambre: Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Journal, February 1, 1910; “La Chambre: Quelques initiatives,” Le Matin, February 1, 1910; “À la Chambre: Motions relative à une promotion spéciale dans la Légion d’honneur,” Le Petit Journal, February 1, 1910.

The Legion of Honor stood at the pinnacle of national awards for honor and virtue. Established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802, the Legion of Honor was and remains the highest French order of merit for military and civic virtues, and questions quickly arose for a special dispensation to the flood’s heroes.

M. Charles Henri Emile Véraux received the Legion of Honor for his long military career and was the commander of the subdivision of firefighters in Saint-Germain. During the flood, Véraux oversaw his company’s rescue efforts. L'Académie Française awarded the Rigot-Goulet Award of 3,200 francs to L’Abri, société de sources à l’époque du terme, which the Press Union had entrusted with the distribution of 200,000 francs to flood victims in need of shelter. Légion d’Honneur: Collection Léonore at the Archive Nationales de Paris, Dossier LH/2686/24; Discours sur les prix de vertu 1910: Discours de M. Frédéric Masson, Directeur de l’Académie Française, December 8, 1910.

Jean Lecoq, “Propos d’actualité. Pour les sauveteurs,” Le Petit Journal, January 29, 1910.

“Les suites de l’inondation,” Le Petit Journal, February 1, 1910.

“La fête de la natation;” “Les réunions d’hier. La fédération des sauveteurs,” Le Petit Parisien, February 7, 1910.