Private Sphere and Public Sphere, Economic Issues and the Judicial Arena: Women and Adultery in Marseilles during the Eighteenth Century

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Criminal Ordinance of 1670 pays particular attention to crimes against morality.[1] Long passages are dedicated to these crimes, some of which identify the crimes in question, while others detail the penalties to be imposed. The principal objective of the Criminal Ordinance was to regulate the behavior of the subjects of the King of France in order to maintain law and order in the land and to define appropriate punishments.

In the list of crimes against morality, jurists and criminologists gave adultery special treatment; they all dedicated long dissertations to the various forms of adultery and related moral and social issues.[2] Citing adultery as a crime was a male privilege: Men alone had the right to bring a case against their spouses.[3] Thus, the law was unfair and unfavorable to women. Yet the provisions in the Criminal Ordinance, as drafted, also contained safe conducts and other alternatives that gave women more protection than might be expected. Indeed, the Ordinance gave judges considerable leeway in exercising their authority. The rigidity with which the law was applied was not due to the Ordinance itself, but rather to the way that judges interpreted it.

Under the Old Regime, marriage was a sacrament and thus indissoluble. However, the law permitted couples in certain circumstances to separate on grounds of discord, but separation did not annul the sacred vows. Hence cases for adultery are of particular interest because they give us an opportunity to understand how couples approached the courts in order to obtain separation and/or a financial settlement. At the time, adultery was considered a crime that offended several fundamental aspects of the social order: morality, sexuality, sociability, and spirituality.[4] It was up to the judges, therefore, to decide how much weight should be give to each of these elements in the cases brought before them. Women were the focal point because they symbolized, to a certain extent, the site where morality, family, and social order converged and because society placed the responsibility for upholding these values more heavily on their shoulders than on those of their husbands. This article reviews documents relating to prosecutions against adulterous women from the criminal archives for the Sénéchaussée (Bailiwick) of Marseilles, an intermediate tribunal between the lower courts of justice and the parlements. It was before this tribunal that the more common cases were brought. The Sénéchaussée's criminal archives cover the period 1750–1789 and contain thirty cases of adultery, twenty of which will be studied here.[5]

Quite apart from the moral questions it raised, adultery was often linked to other more practical questions, whether material or economic. The objective here is to understand the impact that public knowledge of the crime had on both the private and the public spheres and the process by which it arrived before the court. My analysis seeks, therefore, to answer the following question: What were the private and public issues involved in cases of adultery in Marseilles during the late eighteenth century? In my attempt to find answers for this complex question, I will first discuss how adultery was seen in eighteenth century society and then concentrate on an analysis of the unspoken causes of this crime, often referred to as a source of "family disruption"[6] and scandals.

Adultery during the Old Regime: A Female Crime Par Excellence?

Adultery during the Old Regime was defined as "the crime that is committed by the husband or the wife as a violation of the conjugal oath."[7] Although jurists might make fairly subtle distinctions between different forms of adultery (simple or double, for example), they all justified their decision to place adultery in whatever form and its penalties squarely within the jurisdiction of criminal justice by referring to custom and tradition.

As with all moral crimes, the rigor and attention applied to adultery was intended to ensure that royal law and order in the public sphere was maintained.[9] The Criminal Ordinance of 1670 contains a long series of provisions governing evidence for adultery, since "obtaining proof for this type of crime" was particularly difficult.[10] Only the act in flagrante delicto was considered to need no further evidence, but these cases were rare. It is mentioned in only three of the cases studied here. If there was no evidence of in flagrante delicto, how could it be proved that adultery had taken place? Given that, during the Old Regime, people did not differentiate between the "home" as a private sphere and the "world" as a public sphere, the Criminal Ordinance suggested that intimacy could be inferred if the wife was known to walk often with men in isolated public places, if she was seen receiving gifts from men other than her husband, or if she was seen entering a room with a man and kissing him. If these provisions put forward by the judges seem arguable, they nonetheless reflected the reality of social relations during the Old Regime: They existed exclusively in the public sphere, where there was no room for personal privacy.

When we examine the hearing proceedings more closely, we find that adultery was, in the eyes of the judges, a crime essentially committed by women. However, under criminal law during the Old Regime, women were barred from bringing a case against their husbands for adultery. To learn more about adultery, therefore, we must look beyond cases accusing women of adultery. Examining accusations of ill treatment that women brought before the Sénéchaussée, we find references to adultery committed by both husbands and wives and evidence that women did in fact seek to extricate themselves from difficult marriages by denouncing their husbands' behaviour. Loopholes in the Ordinance made it possible for them to circumvent their ineligibility and thus obtain judgment against their husbands. They could lodge a complaint of domestic violence, for example, and then broaden the accusations to include other crimes, such as adultery, which would increase the weight of the initial charges. If women were theoretically legal minors and wards of their husbands, in practice the court did offer them the possibility of lodging a complaint before a judge in circumstances such as serious injury without the husband's consent. In addition, the Great Ordinance placed less importance on female adultery if there was proof of ill treatment or of the husband's adultery.[11] In such a case, the arguments cancelled each other out, and the action could be withdrawn on the grounds of "no case to answer."

Thus, the notion that justice generally served men and discriminated against women has to be qualified. The Criminal Ordinance was flexible and gave judges plenty of latitude to make decisions. To a certain extent, the husband's claims of adultery and the wife's claims of ill treatment were two sides of the same coin. Indeed, the language and form of the complaint for adultery duplicates exactly that for domestic violence: a statement that the disastrous marriage was the source of all difficulties; the list of the husband's virtues placed in opposition to that of the wife's misdeeds; and, finally, a description of the scandal. Thus, the Criminal Ordinance provided women with legal weapons to defend themselves from prosecution by the husband. However, adultery or wife-beating were crimes that did not involve the couple alone, but had an impact on the entire community in which they lived.

Adultery in the Public Sphere

Profiles of contentious couples

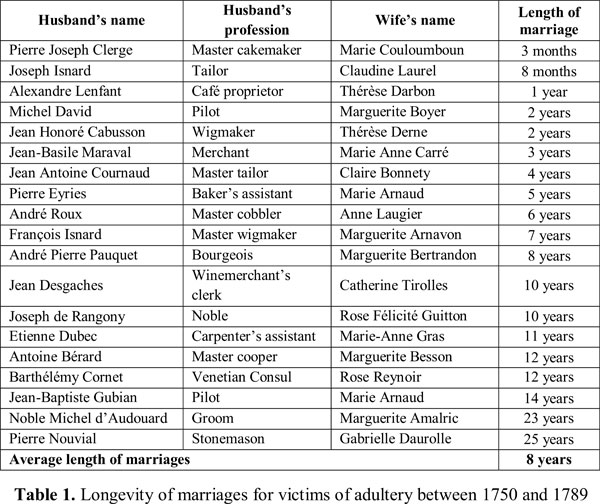

An analysis of the prosecutions and protagonists allows us to discover a number of characteristics about the couples involved in cases of adultery. First, marriage partners were found within the same social circle; generally, people did not marry outside their class.[12] Although most of the cases involved small merchants, the bourgeoisie and provincial nobility were also well represented in cases of adultery found in the criminal archives of the Sénéchaussée of Marseilles. Table 1 provides details about the longevity of the marriages involved.

The average duration of marriages in my study was approximately eight years, and adultery was usually discovered in the first few months or after several years. In most cases, the couples accepted the situation, even though it was common knowledge and publicly acknowledged by the local community. In cases where the age of the protagonists is available, we can see that there was often a large age difference between husbands and wives—usually more than eight, but sometimes as high as twenty years—and relatively no age difference between wives and lovers. This would imply that, where there was unhappiness within the couple, the wife would seek out a lover of her own age in order to find an intimacy that was often absent in arranged marriages.[13]

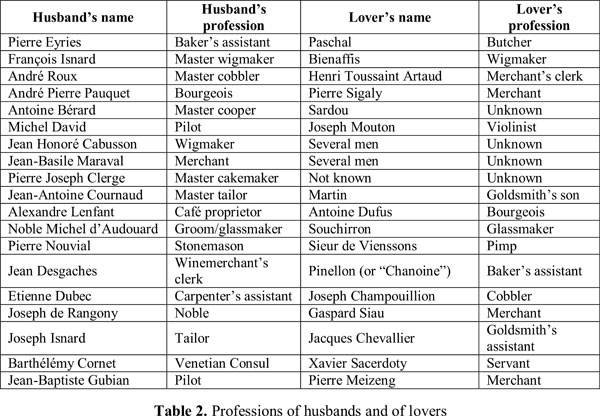

The social profile of lovers was always very close to that of the wives being prosecuted for adultery (see Table 2). Indeed, lovers were often from a similar or the same social circle as the husband, or even the same socio-professional category. While the social rank of the plaintiffs is an important factor in interpreting the testimony, we must look for the underlying reasons why these crimes were denounced by examining the nature of social relations of the period.

Adultery and social relations: neighborhood perception, representation, and condemnation

In order to establish the facts of a case, the courts would call certain witnesses. Although members of the family and servants were usually not allowed to give evidence, the courts often heard testimony from servants in adultery cases. Neighbors were also called as witnesses by husbands to bolster their cases or by the judge to obtain a clearer picture of the facts. It is particularly interesting to note that the majority of witnesses called in the cases described here were women.[14]

Neighbors were particularly attentive and attuned to questions of morality and, especially, of immorality.[15] The neighborhood served as an unofficial and omnipresent agent for controlling social behavior, and nothing escaped its vigilance. Since statements attesting to the existence of criminal liaisons were readily supplied to the judges, we can see how the courts themselves were an extension of the public sphere. In all the cases included in this study, the neighborhood's role was capital. In the first instance, it ensured that rumors spread and that neighbors were informed of social and moral problems among inhabitants who no longer respected the tacit standards governing their community.[16] Also, prosecutions allow us to understand the key role played by the informant as a personification of the neighborhood. The use of expressions such as "public nuisance," "in the district," "it was public knowledge that . . . ," and "being of public notoriety," underscores the fact that living in close proximity with one's neighbors offered many opportunities for watchful eyes to observe and comment on behavior in the street or behind closed doors. Placing the testimony of witnesses in the sphere of "public knowledge" protected them, to a certain extent, from reprisals. Indeed, betrayed husbands often learned from the neighborhood about the exploits of their wives. Joseph de Rangory, for example, said that his wife

The husband and the neighborhood were both scandalized, the former being informed by the latter of the various forms of deviance that could occur and cause disorder in the quarter. In addition to the risk of exposure to public ridicule, the breakdown of social relations and the stain on the husband's honor might prejudice his own standing in the neighborhood.[18] Beyond reporting and denouncing a moral crime, statements by witnesses provide information about an entire social system of relations with third parties. In fact, they betray the witnesses' curiosity about their neighbors and demonstrate the ways in which they pried into the lives of others. In this group of cases, for instance, we can see that physical, as well as personal, proximity encouraged people to take an interest in the lives of others. Servants, whose presence in the household indicated the social rank of the couple involved, lived closest to the protagonists, which often led to their assuming the role of go-between. Thus Anne Audoyer, housekeeper for the Rangory couple, claimed that not only would the lover of her mistress be present when she dressed in her bedroom, but also

A witness in another case stated that, while paying a visit to the wife of François Isnard, he had "been curious enough to look through the keyhole,"[20] and he saw that the wife was at home, contrary to what she had led him to believe. The archives of the Sénéchaussée are rich troves containing a wide variety of terms used by neighbors to report essentially the same situations. In contrast to cases of domestic violence where testimony generally went against the husband, witnesses, including those brought by the wife, usually sided with the husband in prosecutions for adultery. Of the statements provided by 151 witnesses, 94 percent favored the husband. This, of course, can be partly explained by the fact that husbands, not wives, had the sole right to bring a complaint against their spouses for adultery. Witnesses' statements allow us, therefore, to understand the causes of adultery, even if the complaints made by plaintiffs tend to be short on details.

Forms of adultery

Adultery took several forms, but most cases fell into one of two categories. Either the husbands accused their wives of having a lover (70 percent of my cases) and cited a number of other crimes such as cohabitation, debauchery, or illegitimate pregnancies. If they could not identify their wives' lovers, they accused their spouses of prostitution and other crimes such as brothel-keeping, scandalous lifestyle, or public disorder. All the cases in this study fall into one or the other of these categories and contain references to "causing a public scandal" by both the plaintiffs and the witnesses.

To illustrate these points, let us examine the prosecution instigated by the navigator Michel David, aged thirty-two, which is an apt example of the discovery and denunciation of adultery. After boarding his ship in Toulon and passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, his ship met with a violent storm and ran aground on the coast of Portugal. The crew set out for Cadiz and then Malaga where Michel David took ship for Toulon. On his arrival, he hurried to Marseilles without informing his wife. David's testimony continues:

In my collection of cases, there are only two involving in flagrante delicto, that is, where the husband found the lover hidden under the bed or actually in bed with her. Once again, we see that the presence of neighbors in the couple's private sphere was perfectly acceptable. Indeed, private life was above all a public affair, openly exposed to the social group to which the protagonists belonged.

From the Public to the Private Sphere: Analyzing the Motives for Adultery

Even though the concept of private and public spheres is more usually found in discussions of French society in the nineteenth century, it appears that such a distinction was already emerging in the eighteenth century. Here the expression "private sphere" refers not to the household's intimate space, but to certain aspects of personal appearance or behavior that disclosed the individual's lifestyle to public scrutiny: physical signs of venereal disease, slovenliness, or blatant conduct that implied a dissolute life. By drawing attention to him or herself in this way, his or her behavior became part of the "public sphere" since it exposed the individual to public scrutiny. When the behavior occurred outside what the marital bond permitted, it was interpreted as scandalous by the neighbors and could be interpreted as proof that social standards, and hence social order, had been transgressed. The "public sphere," therefore, was solidly rooted in social interaction and social behavior during this period.[22] Street rumors and information provided by neighbors, themselves a source of public debate and rumor, ensured that there was a continuous interplay between the private and the public sphere.

Official reasons for adultery

Public dishonor, violation of the sacred bonds of marriage, and public scandal were the arguments usually put forward in complaints denouncing adultery. Regardless of the crime invoked in the official complaint, the rhetoric of the complaints was filled with pathos. Neighbors noticed the disorderly and irregular lives of others. As in wives' complaints about domestic violence, men did not hesitate to denounce the violent acts they suffered at the hands of their wives. For example, Pierre Eyries, a baker's assistant, complained that his wife had stabbed him several times with a knife.[23] The birth and acknowledgement of illegitimate children, quite apart from the dishonor they implied, could have a serious impact on such practical matters as inheritances.[24] Thus, Etienne Dubec was upset that "the said Grasse [his wife] did not blush to incite her children to call the said Champoullion their father, which she did publicly, and, when the time came to baptize them, she used the plaintiff's name and told the parish priest that the plaintiff was away from home."[25] Thus, the wife could be accused of several moral crimes at once and consequently receive a heavier sentence than usual. Witnesses' statements were filled with a wide range of phases implying dishonor, such as "infamy," "disgrace," "shame," and "scandalous disorder." The situation became even more serious when the plaintiff's very flesh was tainted by venereal disease passed on by his unfaithful wife. Such physical evidence proved the defendant's guilt and increased the social visibility of the crime to such an extent that it was important to punish the guilty party in order to silence scandal-mongering by the neighbors. Five cases out of twenty mention syphilis. Suspecting his wife of having a liaison, Jean Antoine Cournaud claimed that "from this commerce, the said wife transferred a venereal disease to the plaintiff and at this time the plaintiff could no longer harbor any doubt about his wife's debauchery." Surgeons treating these diseases were called to give evidence and confirm the grievance.[26]

Other reasons for adultery

The public aspects of adultery only represent some of the reasons why this moral crime would be brought before the courts. Financial questions were raised in 25 percent of the cases as the principal reason for making a complaint of adultery. In fact, some husbands who had not lived with their wives for several years suddenly remembered that their honor had been flouted and decided to take their revenge. Money matters were just as important for the elite as for the working classes in Marseilles. Let us look at the case of François Isnard who, in 1760, left for Spain to make his fortune. On his return, he learned "by public rumor" that his wife was living with another man. As proof of his wife's guilt, he attached to his statement the letter that his wife had sent him shortly before he returned to Marseilles. It reads: "Shameful and miserable man, you are very bold to write and tell me that you will come and greet me after New Year's Day, is your soul so low that after you caused me sorrow and made me lose my honor and reputation and possessions, your privilege is sold, Mr Vasseur denuded you and ruined me."[27] The rest of the letter is full of messages and warnings. Thanks to the testimony of witnesses, we learn that Isnard's wife had sold his goods in order to give money to her lover. In another case, André Pierre Pauquet, a bourgeois, lodged a complaint about the way he had been manipulated and forced into a marriage contract with Marguerite Bertrandon, who was five years his senior—an uncommon occurrence. The victim stated that his goods and assets had excited his wife's greed and that she had used them for her family and her lover. An accusation of adultery could also give an unscrupulous husband an opportunity to take control of part of his wife's assets, particularly her dowry.[28]

Separation of the couple and the division of assets were perfectly legal procedures during the Old Regime. A woman's assets could be returned to her if it could be proved that the husband had been negligent in managing or selling his wife's property. Thus, the wife could pursue her husband before the courts in her own name in order to maintain control of her property. Separation could be authorized in cases of ill treatment, for example, or the husband's irresponsible acts toward the family. Thus, the wife could bring an action before the courts requiring the division of assets in order to gain judicial protection from her husband's misdeeds. In such situations, if the court decided in her favor, it could also issue an order preventing the husband from entering the family home. On the other hand, if the husband could prove that his wife was guilty of a moral crime, he could ask the court to dispossess her of her dowry.[29]

Immoral behavior implied that the woman was incapable of managing her property, necessitating the transfer of the control of her assets to the husband. In fact, "it is ordained that she shall be deprived of her dowry, her right of primogeniture, and of any monies to which she had legal claim under the terms of her marriage contract, and that her dowry shall be transferred to her husband, who in turn will pay her an allowance as determined in the judgment."[30] However, the wife could not be stripped of her inalienable property—even when convicted for adultery. In the cases studied, the dowry was a key issue: Either one had not been paid despite the marriage, or it consisted of money and other belongings that the wife took with her during her flight, thus stealing her husband's rights to her dowry.[31] A contract signed before the notary gave details of the assets provided by the wife in her dowry—"clothes, jewels, furniture, linen, utensils"—in short, all the usual objects found in a bride's chest.[32] All the household linen was marked in order to distinguish which pieces belonged to whom. One of the witnesses, Jeanne-Marie Derudier, stated that she had seen the wife of a plaintiff change "the mark on the sheets which were in the name of her husband in order to replace it with her own."[33] In one of the sentences pronounced against Marguerite Arnavon on 9 July 1764, the wife of François Isnard was condemned in absentia to imprisonment in the Convent of the Refuge for two years as a lay sister.[34] The husband was given two years to decide whether to accept her back. If, at the end of this period, her husband decided against releasing her, "the said Marguerite Arnavon shall have her head shaved and veiled until the end of her days and shall be deprived of her dowry, her marital rights and advantages which shall be acquired and confiscated as a fine and as compensation to the said Isnard, her husband."[35] Imprisonment at the Refuge was not free of charge, however, and a husband wishing to leave his wife there had to pay her living expenses. In all the prosecutions studied for this article, there were three sentences in absentia for imprisonment at the Refuge, and one internment in a convent was actually carried out.[36] Some of these women managed to flee, but, in doing so, they left the usufruct of their dowry to their husbands. However, if the husband did not have the necessary resources, he could send his wife to the hospital for the rest of her life.[37] In another case, involving a Venetian consul, Barthélémy Cornet, and his wife whom he accused of adultery, there were significant financial issues to be resolved because the wife's dowry was worth more than fifty thousand pounds. We can easily understand why the husband was so keen to have his wife found guilty! But behind these domestic disputes over money, there were signs of other recriminations that do not necessarily appear in the court's proceedings.

Adultery, or How to Achieve Emancipation of the Sexes?

The women brought to trial for the crime of adultery were often wives who had either been abandoned or married against their will as part of marriage strategies that had little to do with love. Many women chose to escape with their lovers in what we might call the "Manon Lescot syndrome," that is, denying one's past life and starting anew with another for no other reason than passionate love. Thus, Marguerite Bertrandon fled with her lover to Cap Français in Haïti in order to devote herself totally and freely to her passion and her love. Other attempts were less successful: In November 1759, Claudine Laurel stole her husband's money and escaped with her lover to the nearby port of La Ciotat, where they were arrested by the husband once he heard about their plans. In another case, a witness gave information that was not always mentioned in the initial complaint: true love. Thus the lover of Marie Ollivier said to the husband after being caught, "I beg your pardon, but I loved your wife before you." The wife confirmed the lover's statement, adding that she had "married him [her husband] . . . against her will."[38]

Prosecutions for adultery brought before the Sénéchaussée of Marseilles provide interesting material for the study of marriages during the Old Regime. They offer very useful insights into the mechanisms for constructing and preserving family interests, which took precedence over emotions. Placing adultery squarely in the public sphere contributes to the reinforcement of the absence of privacy and of the pressure to conform, tacitly provided by the neighborhood as part of daily life in the community. Adultery raised serious moral, social, and economic questions. But documents relating to prosecutions for adultery contain the first signs of a desire for the freedom to love. Scorned husbands (or at least those who claimed to have been scorned) might have perceived such a desire as a violation of social morals. Yet the breaking of marital vows and reciprocal obligations in adultery could be interpreted as an act of liberation from the social rules dictated and applied by the throne and the church. Later this freedom would be confirmed (for a while at least) during the French Revolution when new legislation on divorce was enacted in 1792. Indeed, the Law of 1792 formally stated that, since arranged marriages often gave rise to the principal grievances described in the prosecution documents in my study (dissolution of morals, abandonment of the marital home by a spouse, incompatibility, etc.), people could now marry according to their own desires, rather than respect the dictates of family, crown, or church.

Pierre-François Muyart de Vouglans, Les lois criminelles de France, dans leur ordre naturel, dédiées au roi, 2 vols. (Paris, 1781); Daniel Jousse, Traité de la justice criminelle de France, 4 vols. (Paris, 1771).

La répression de l'adultère en France au XVIe et au XVIIIe siècle, (Brussels: Centre de droit comparé et d'histoire du droit de l'université libre de Bruxelles, Story Scientia, 1990). See also Arnaud Canu, Ingrid Leguedois, David Colin, and Marc Savoye, "La répression de l'adultère du XVIe siècle à nos jours," in Yves Jeanclos, ed., Les délits de nature corporelle et sexuelle en France et en Europe du XVIe siècle à nos jours. Actes des séminaires d'histoire du droit penal (Strasbourg: Université Robert-Schuman, 1997), 157-85.

Encyclopédie méthodique, ou par ordre de matières (Paris, 1782), 179-86.

Agnès Walch, Histoire de l'adultère: XVIe–XIXe siècle (Paris: Perrin, 2009).

Before 1750, there were very few records of criminal cases. According to the Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône in Marseilles, the Sénéchaussée's criminal archives before this date were probably lost or destroyed. After the Revolution in 1789, the Sénéchaussée was replaced by a Revolutionary Tribunal, and justice was not delivered in the same way.

Arlette Farge and Michel Foucault, Le désordre des familles: Lettres de cachet des archives de la Bastille au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Gallimard, 1982).

Encyclopédie méthodique, ou par ordre de matières (Paris, 1782), 179-86.

Ibid. Please note that punctuation has been modernized for clarity.

"This crime creates trouble and confusion in the social order. It banishes the good morals that sustain it. It weakens the political structure by irritating its members. It renders them guilty of the worst crimes." Ibid.

Ill treatment of the wife by the husband could reduce the penalty for adultery because it could, to a certain extent, be considered the cause of the wife's adulterous act.

Alain Girard, Le choix du conjoint, une enquête psycho-sociologique en France (Paris: PUF, 1981); Pierre Bonte, Épouser au plus proche: Inceste, prohibitions et stratégies matrimoniales autour de la Méditerranée (Paris: Éditions de l'EHESS, 1994). The study of marriage contracts, where available, would give us more knowledge of matrimonial strategies; see Pierre Roussilhe, Traité de la dot, à l'usage du pays de droit écrit et de celui de coutume (Clermont-Ferrand, 1785), 46.

Alain Lottin, La désunion du couple sous l'Ancien Régime: L'exemple du Nord (Paris: Éditions universitaires, 1975). Sabine Melchior-Bonnet and Catherine Salles, Histoire du mariage (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2009).

This is due to the fact that women were more likely to spend their days in the streets than men; see Christophe Regina, "Discours normatif et normativité du discours: Le témoignage sous l'Ancien Régime à Marseille dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle: une affaire de femmes?," in Claudio Povolo, ed., Testimoni e testimonianze del passato / Witnesses and testimonies of the past (Koperr: Acta Histriae, forthcoming).

Christophe Regina, "Voisinage, violence et féminité: Contrôle et régulation des múurs au siècle des Lumières à Marseille," in Judith Rainhorn, ed., Vivre avec son étrange voisin. Altérité, et relation de proximité dans la ville (XVIIIe–XXe siècles) (Rennes: PUR, 2010), 217-35.

François Ploux, De bouche à oreille: Naissance et propagation des rumeurs dans la France du XIXe siècle (Paris: Aubier, 2003); Arlette Farge, Dire et mal dire: L'opinion publique au XVIIIe siècle (Eure: Le Seuil, 1992); Pascal Froissart, La rumeur, histoire et fantasme (Paris: Belin, 2002); Michel-Louis Rouquette, Les rumeurs (Paris: PUF, 1975); Michel-Louis Rouquette, "La rumeur comme résolution d'un problème mal défini," Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie 86 (1989): 117-22.

Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône (AD BDR), Marseilles, 2 B 1712 N° 24, 1787.

Thelma S. Fenster and Daniel Lord Smail, Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003).

Arlette Farge, Vivre dans la rue au XVIIe siècle (Paris: Gallimard, 1979).

Renée Barbarin, La condition juridique du bâtard d'après la jurisprudence du Parlement de Paris du Concile de Trente à la Révolution française (Mayenne: Floch, 1960); Claude Grimmer, La femme et la bâtard (Paris: Presses de la Renaissance, 1983).

Jean-Philippe Agresti, "La demande de séparation de biens en Provence à la fin de l'Ancien Régime: une action protectrice pour la femme mariée," in Patrick Charlot and Éric Gasparini, eds., La femme dans l'histoire du droit et des idées politiques (Dijon: E.U.D, 2008), 61-92.

In comparison, the status of widows and single adult women was more favorable as they were accorded greater independence and the ability to exercise certain powers.

Sarah Hanley, "Social Sites of Political Practice in France: Lawsuits, Civil Rights, and the Separation of Powers in Domestic and State Government, 1500–1800," The American Historical Review 102, no. 1 (1997): 27-52.

Legal term meaning "in the absence of the defendant" (translator's note).

Christophe Regina and Philippe Gardy, Lucifer au couvent. La femme criminelle et l'institution du Refuge au siècle des Lumières (Montpellier: Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2009).

Encyclopédie méthodique 179-86 : "When the adulterous wife is poor, the husband may ask, and the judge may order, that she be sent to the hospital, instead of the convent, and there be treated in conformity with the rules applicable to debauched women."