Women and Gender in the Croix de Feu and the Parti Social Français: Creating a Nationalist Youth Culture, 1927–1939

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

By 1939, the Croix de Feu (1927–1936), and its successor, the Parti Social Français (PSF, 1936–1940), reported a membership of 1.2 million, including some 200,000 to 300,000 women.[1] Both figures remain unprecedented in the history of French political movements.[2] The Croix de Feu/PSF featured a program that sought to remake French society in their own image: politically authoritarian and culturally ultranationalistic. Socially, the movement posited an organic unity among all French women and men based on an ethno-religious conception of French national Catholic identity. Most of the movement's members believed that national unity was necessary to fend off divisive forces that threatened the cohesion of French society, namely communism, socialism, and feminism. While historians have vigorously debated whether the Croix de Feu and PSF were fascist, Michel Dobry, Kevin Passmore, and Sean Kennedy have suggested that scholars move beyond interpretative issues of classification and ask a "fuller range of questions" about the Croix de Feu and PSF.[3] Moreover, despite women's central role in the shift of the Croix de Feu/PSF from a small veterans' league to a mass movement, the scholarly literature on both women and gender in the organization remains underdeveloped.[4] It is in this vein that this essay will show that women's sheer numbers and the scope of their activities are primary reasons for the movement's unparalleled growth during the 1930s.

The influx of women into the Croix de Feu beginning in 1934 fundamentally transformed the movement's recruitment strategies, propaganda activities, and ideological outlook. From 1934 to 1939, women designed the organization's social programs that mostly comprised social service provisions and youth development, both of which ultimately served hundreds of thousands. Women's abilities to attract and create a cadre of ultranationalistic young women and men and to attract youth living in so-called "red" neighborhoods were crucial components of this growth. Working with youth served as an entrée for politically reactionary women to join the Croix de Feu/PSF. As women increasingly became the public face of the movement's grassroots activities, their nominally charitable social services sought to provide a veneer of moderation to counter its violent reputation, eventually making the organization palatable to the French populace.

The limited activities permitted to women and youth in the hyper-masculine, paramilitary Croix de Feu from 1927 to 1934 paled in comparison with the sophisticated programs that PSF women developed in the late 1930s. While the Croix de Feu created its first auxiliary group in 1931 for sons and daughters of Croix de Feu members (the Fils et Filles des Croix de Feu, or FFCF), adult women and non-veteran men had to wait until 1933 to have their own group. The FFCF was for both sons and daughters, although league leaders devoted most resources to sons, advising them that they would be the future leaders of France. In contrast, the male leadership told daughters that if they wanted to become proper women, they must be agreeable and non-confrontational. In this way, girls could achieve their dream of eventually maintaining a home and teaching their own children to "love their country."[5] From 1927 to 1934, the Croix de Feu espoused an unoriginal and limited familialist ideology that restricted women's activities and ensured that its social and youth services remained relatively small in scope. The league did not yet have a social program, and the only activities that women (primarily wives of Croix de Feu members) organized for children were field trips to culturally significant sites and participation in Croix de Feu parades. The women who volunteered their time to work with Croix de Feu youth did not operate within a formalized structure, and it was left to individual initiative to coordinate youth activities.

The development of the Croix de Feu's social program was accelerated by the massive street riots of 6 February 1934 that brought down the French government and nearly toppled the Third Republic. The nationalist and veterans' groups who initiated the riots generally believed that France's inept parliamentary government encouraged corrupt and selfish politicians to look out for their own self-interest and shirk their national duties. Robert Paxton contends that the riots and their aftermath initiated a "virtual French civil war" between nationalist and leftist groups in the mid-1930s.[6] These political tensions, combined with the economic depression and the growing strength of the Communist party, led most members of the Croix de Feu to believe that their movement served as a crucial force for national reconciliation. The riots created a greater sense of urgency among Croix de Feu leaders to seek solutions to France's social problems by molding a new cadre of disciplined, nationalistic young men and women who would provide stability to French society. These leaders believed that reforming politics was only part of the solution, and that wide-ranging social reform was a prerequisite for political change.

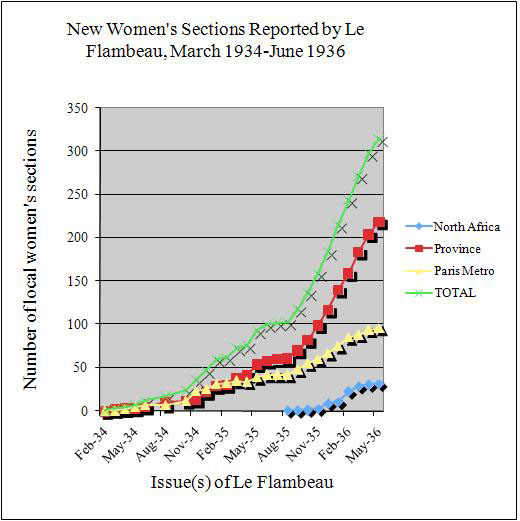

Only a month after the February riots, several Croix de Feu women, led by Antoinette de Préval, created a Women's Section to mobilize on a mass scale women who could develop a comprehensive social program to remedy the political and social shortcomings that precipitated the riots. Immediately, Croix de Feu women began grassroots recruiting to entice their friends, neighbors, family, and business associates to join the new Women's Section.[7] The clear leadership structure and street-by-street recruiting efforts by women led to a dramatic increase in local women's sections from 1934–1936, as shown in Figure 1.[8]

Figure 1.

Over a twenty-six month period, the movement's newspaper, Le Flambeau, reported the creation of approximately 315 new local women's sections: 96 were in the Paris metro region, while 219 were located in the provinces, including at least 32 in the North African colonies.[9] Significantly, the local women's sections became the primary instrument to instill Croix de Feu ideology among French youth. By November 1934, local sections comprised a minimum of fifty members, and each neighborhood section was led by an appointed First Delegate who doled out seven leadership positions, three of which were youth oriented.[10] As the women's sections grew, so too did the scope of the movement's youth initiatives. By October 1935, five thousand young people reportedly joined new Croix de Feu youth groups in Paris, and fifteen thousand had joined provincial groups.[11]

A primary reason for the massive influx of women into the Croix de Feu was that, as members, they had substantive and consequential opportunities to create a nationalistic youth culture that served to counter Communist youth programs. Once organized, the Women's Section created three new youth groups based on age, two of which were divided by sex. The primary goal for all three groups, "to develop in children a national spirit," underscored the league's ultranationalistic ideology.[12] In practice, this meant that the delegates in charge of the three groups took youth to museums, important historical sites, and national parks. Touring battlefields was a crucial component of socializing young men and women to understand the significance of the sacrifices that veterans made for the French patrie. Youth in all three groups enrolled in age-specific Croix de Feu courses that focused on the positive aspects of a glorified French history, the "great" French writers who constructed the canon of French literature, and the civilizing mission of the French Empire.[13]

All Croix de Feu youth were entitled to a "patriotic education," although the membership of the three groups necessitated age- and gender-specific pedagological objectives. The youngest Croix de Feu children were part of a gender-neutral "Group A," which comprised boys and girls from seven to thirteen years of age. In an effort to get not only children but their parents excited about the Croix de Feu, the Women's Section wanted Group A children to associate Croix de Feu activities with fun. In addition to field trips and courses, the Women's Section supervised the children in after-school activities that included games, study time, and work in arts and crafts studios. They also organized a multitude of nationalistic celebrations. The annual Christmas party was particularly significant, because, in the eyes of Women's Section leaders, the celebration of Christmas was an opportunity to remind children of France's Christian roots. These celebrations drew large numbers; for instance, police reported that the Women's Section restricted parents from attending a Christmas party in Paris at the 3,600-seat Cirque d'Hiver because the location was not big enough to hold both the children and their parents.[14] A Women's Section report from the end of 1935 claimed that Group A was active in all the Parisian women's sections and seventy-five percent of suburban sections. This same report noted impressive growth from October to December of 1935, when the national membership of Group A increased from four thousand to twelve thousand.[15]

As children reached the age of thirteen—and not coincidently entered puberty—the Women's Section separated the girls from the boys, signaling the passage out of childhood. As soon as the children left Group A, the Women's Section socialized Croix de Feu girls and boys to prepare for their future roles both within the movement and in French society. Comprised of boys aged thirteen to sixteen, Group B was intended to strengthen what Women's Section leaders believed were men's innate leadership qualities. Notably, since the female leaders believed that leadership was a natural male characteristic, they restricted women from supervising Group B and appointed a male delegate to oversee its activities.[16] They were convinced that only men could teach boys a uniquely masculine form of morality built on three militaristic ideals: altruism, discipline, and consciousness of duty. These values derived in part from the militarism that pervaded Croix de Feu discourses since its founding as a veterans' league. Moreover, these masculine ideals underpinned the ways in which the league expected young men to serve the patrie. One Women's Section report stated that in Group B, young men would learn that "[t]he important part . . . is, above all, moral order." The Women's Section instructed the Group B delegate that his job was to "create in them [young men] a profound sense of life, develop their altruistic qualities, make them conscious of their responsibilities, and amplify their spiritual, intellectual, and manual possibilities."[17] They added that the Group B delegate was to act as a role model for young men, embodying "perfectly the Croix de Feu spirit and its profound mystique."[18] Female leaders appointed the male supervisor, who worked at youth centers and summer camps to supervise boys in activities ranging from homework to physical education.[19] In this way, the Women's Section sought to ensure that the Croix de Feu retained its dynamism by instructing boys and young men what it meant to be a Croix de Feu man.

Paradoxically, while women could not mentor young men, the female first delegate of each local women's section was not only in charge of appointing male supervisors, but those male supervisors were expected to conform to directives established by the Women's Section.[20] This is a clear case of the complicated gendered hierarchies at work in both the Croix de Feu and later in the PSF. While women were restricted to developing social programs, still they often worked with men on a daily basis in organizing the activities of their local sections. Moreover, as they worked autonomously to direct and run social programs, women leaders often supervised men working with youth. In this case, power did not operate in a top-down manner, but instead was diffused throughout the movement between men and women according to the needs of the league's programs (political or social) and services (election committees or youth services).

Although Women's Section leaders believed that women were inappropriate role models for young men, they did want women to mentor the younger women who comprised "Group C." With members ranging in age from thirteen to twenty-five, the purpose of Group C was to reach "future Mothers, upon whom France's future depends."[21] The Women's Section placed a great deal of responsibility on the shoulders of the Group C delegate, stating: "[T]he duty of the Delegate is as follows: develop in her group the spirit of camaraderie oriented in gaiety and discipline towards intellectual culture; to prepare wise propagandists: to render them worthy of contributing effectively to Croix de Feu social work."[22] Whereas masculine traits, such as bravery and responsibility, centered on action, feminine ideals focused on outward displays of emotion and temperament. The Croix de Feu wanted women who were light-hearted, cheery, agreeable, and non-confrontational. Both men and women were to be wise and disciplined, but to different ends. Public perceptions of Croix de Feu women's temperament had practical implications for recruiting men and women who were politically not inclined to support a league infamous for violence and intimidation. As part of the league's initiative to present itself in a moderate manner, it was vital that Croix de Feu women appeared comforting and reassuring in their daily interactions with non-members. Both league leaders and the Women's Section believed that proselytizing by these joyful recruiters embodied the league's ideological emphasis on unity, which would offer a corrective contrast to the paramilitaristic violence for which the Croix de Feu was notorious.

The young women of Group C were obliged to enroll in a "social service" course created by one of the Women's Section social service leaders, Madame Suzanne Fouché. Fouché mandated that only qualified professionals at Group C's foyer teach the course. The curriculum included classes in home economics (cooking, sewing, household maintenance, hygiene), academic subjects (history, literature, foreign languages), professional training courses (typewriting, stenography), and physical education.[23] The curriculum also had an "artistic" component that involved joining a chorus (to learn regional songs) and learning lace-making and embroidery. The obvious objective of the course was to train girls to run a home and become mothers. However, as Kevin Passmore has pointed out as well, it would be a mistake to reduce the Croix de Feu's vision of ideal femininity to familiast.[24] One of the most important aspects of the movement's ability to mobilize women was its emphasis on creating effective propagandists and recruiters, two activities that went beyond Croix de Feu maternalist notions of femininity that had dominated the league's discourses from 1927 to 1934. In this way, the Women's Section worked to broaden the league's discursive conceptions of ideal femininity. Since Group C objectives mirrored women's duties once they joined the Croix de Feu, their purpose was to prepare girls to make a smooth transition to active and productive membership. The Women's Section deployed gender in a dynamic manner that offered young women in the Croix de Feu a range of participatory options, which included running a household, working with youth, recruiting for neighborhood sections, propagandizing for the movement, and designing and developing social programs.

In order to reinforce gender distinctions, the Women's Section physically segregated girls and boys with separate spaces for them in Croix de Feu youth centers. Groups B and C had their own foyers, although the Women's Section explicitly barred the young women of Group C from entering Group B's library.[25] Since the goal of the centers was to create a sense of discipline and camaraderie among youth, especially male youth, the Women's Section sought to avoid the interaction of boys and girls in learning environments. Women's Section leaders sought to create atmospheres conducive to same-sex interactions in order to reinforce a "spirit of teamwork" and a sense of collectivity which was gender specific.

In 1935, the Women's Section initiated the creation of several new youth centers in Paris and across France for two primary purposes: to attract families in working-class neighborhoods and to provide public space where Croix de Feu members and youth could socialize. The first center, strategically located in the northern Paris suburb of Saint Ouen, a Communist Party stronghold, was organized in 1935 by the most powerful woman in the Croix de Feu, Antoinette de Préval. As the force behind the creation of both the Women's Section and the multitude of Croix de Feu social services, de Préval wanted this center and others like it in so-called "red-districts" to attract neighborhood youth by making the center an enjoyable place to visit.[26] As one Croix de Feu woman put it, "[We want to] infiltrate the families without scaring them away and to persuade them to send their children to the center. [We will] make them understand that we want to help them morally as well as financially."[27] When it first opened, the center's activities encompassed services already provided by local women's sections: after-school day-care, clothing and food distribution, day trips, medical consultations, and social activities.[28] The actual layout of each center varied, but the one at Saint Ouen was 3,970 square meters and included a Group C foyer, classrooms, offices, a clothing depot, and space for physical education programs. One of its most important features was an arts and crafts studio, which included space for tin working, ironworking, woodworking, sheet-metal working, and joint-fitting.[29]

The Women's Section had to live through some growing pains on its way to establishing a functional youth center. While the social services provided by Saint Ouen provided aid to many families, the children's arts and crafts studio struggled when it opened. One report observed that only five children used its tin workshops, noting with rancor that those children were "a gypsy, an Italian, an illiterate, and two half-crazies." Only one child used the woodworking studio, but the report claimed that at least he was a "healthy French boy."[30] Other problems included a director who did not like children and whose anxious temperament made her better suited to work "behind a desk," difficulty in staffing for several courses, and classes that were "too dry." The report also pointed to several external barriers to success, including the local mayor who wanted children to attend municipal classes, poor parents who needed their children to work, and children who preferred to "lounge around" or sell their wares "on the sly."[31] Croix de Feu leaders proposed several solutions to these problems, such as keeping the director away from the children and better publicizing the need for teachers. The staff could turn the studios into a "school for French popular art," where children would fashion tin into boxes for spices, milk, and other goods, and carve wood into airplanes, boats, or figurines. The children could then sell their wares at a Croix de Feu charity bazaar, keeping a percentage of the profits, while funneling the remaining proceeds back into the center. Croix de Feu leaders hoped that such changes would demonstrate to parents that their children were in good hands. As one report put it, the improvement "would thus represent a means . . . of reassuring parents about the boys' immediate future, [while] forming in them [the boys] the spirit of teamwork which will give them more confidence in themselves, and in us."[32]

Among all the center's initial challenges, poorly disciplined children were most problematic to Women's Section leaders. The militaristic Croix de Feu ideology stressed discipline among its members, from the leadership to the rank and file. Yet, the women at Saint Ouen struggled with unruly children. When the center opened, the staff quickly expressed dissatisfaction with the behavior of the fifty-two children attending. One report noted that "[t]he children [are] very undisciplined and in the majority of cases, true little savage beasts."[33] Blame for this rested squarely on women's shoulders. One report commissioned by the Women's Section recommended that the female leaders "avoid placing women as supervisors [as] boys of this age don't like to obey them."[34] Clearly Croix de Feu women assumed that only men possessed the moral fortitude necessary to effectively discipline unruly boys. The initial challenges faced by the Saint Ouen's arts and crafts studio were emblematic of the broader struggle to entice neighborhood families to participate. Women's Section reports reveal that local families initially were "rather cold, and, even often suspicious" of the center. With time, however, the center's services won over more families, and the children appeared to become open to order and discipline.[35] It is highly unlikely that these strides were the result of keeping Croix de Feu women away from the boys. More effective leadership and better staff training more likely contributed to these improvements. One report, for instance, praised the center's young male and female supervisors for their patience and gentleness with the children.[36]

The Saint Ouen center closed upon the Croix de Feu's dissolution in June 1936, but reopened five months later after the league was reconstituted as the PSF Party. While one scholar has suggested that the dissolution resulted in "women's reduced importance in the movement," in fact, the influx of women and expansion of their activities actually continued in the PSF.[37] Just as in the Croix de Feu, the PSF depended on women's grassroots activities to combat communism at the neighborhood level. The PSF's new and vaguely named Work and Leisure association took over and expanded many Croix de Feu youth programs, particularly the youth centers and summer camps. Led by Antoinette de Préval, Work and Leisure opened new centers in Paris and the provinces, all sharing the same simple goal of getting children and parents to attend. As de Préval repeatedly stated, if nobody came, all their work would be useless.[38] Accordingly, Work and Leisure leadership decided that the best way to entice neighborhood families was to make each center appear apolitical by hiding their PSF affiliation. As one PSF section president put it, they wished to "inculcate the PSF spirit, but without the label."[39]

The attempted subterfuge did not fool Communist Party officials living in the neighborhoods around the new youth centers, as they were well aware that Work and Leisure was associated with the PSF. In Aubervilliers, Communist officials responded to a newly created center with a publicity campaign alerting parents of its PSF affiliation. A Communist bulletin warned that "[t]he goal of this organization [Work and Leisure], which gives itself a philanthropic character, is to exploit the misery or the naivety of people for political ends."[40] Even the police kept PSF social centers under close surveillance. In 1938, an informant reported to them that Saint Ouen was working with a neighborhood iron works company to establish an arms depot. Upon further investigation, the police found no contraband, although PSF arms caches were found elsewhere in France.[41]

While the Saint Ouen center had experienced difficulties when it opened, between 1936 and 1939, it eventually became a model center. Stable and continuous leadership provided by the new director and her five adjutants, coupled with the experience of the staff of thirty-five (mostly women), were primary reasons for the improvements.[42] Work and Leisure reported that by the end of the 1930s, about two thousand children had enrolled in the center, and that over five thousand families had benefited from its social services.[43] The center continued to operate during the war and occupation, providing aid to refugees and deportees, until the Gestapo closed it in 1943 for reportedly engaging in clandestine resistance activity.[44]

By the mid-1930s, the slogan of the Croix de Feu/PSF had become "Social First!," indicating the prominent position social issues played in the movement. The organization depended on the Women's Section at every level to create and execute its comprehensive social and youth development programs: as leaders in the design and implementation of such programs, as mid-level directors of local women's sections, and as foot-soldiers vital to youth recruitment and supervision. Women's high level involvement at youth centers such as Saint Ouen reveals the intersections between the discursive realm of gender ideology embodied in the movement's youth curriculum, and the everyday activities of women who were on the frontlines of neighborhood battles with rival political groups for the allegiance of local families.

The figure for the movement's membership comes from Jean-Paul Thomas, "Les Effectifs du Parti Social Français," Vingtième Siècle 62 (1999): 61. For women's membership, see Thomas, "Les Droites, Les Femmes et le Mouvement Associatif, 1902–1946," in Claire Andrieu, Gilles Le Béguec, and Danielle Tartakowsky, eds., Associations et champs politique: La loi de 1901 à l'épreuve du siècle (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2001), 524.

Thomas states that the PSF was the only political party in French history to achieve membership of 1.2 million. I would add that if 200,000 to 300,000 women joined the PSF, this rate would also be unmatched for a political movement. The social Catholic Ligue Patriotique des Françaises (LPF), founded in 1902, obtained a membership of over one million by the 1930s. However, since French women would not obtain the franchise until 1944, LPF women operated outside of the electoral system. For a discussion of women's membership in a variety of sociopolitical groups, see Paul Smith, Feminism in the Third Republic: Women's Political and Civil Rights in France, 1918–-1945 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996); Steven Hause, with Anne R. Kenney, Women's Suffrage and the Social Politics in the French Third Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); and Gill Allwood and Khursheed Wadia, Women and Politics in France, 1958–2000 (London: Routledge, 2000).

Quoted in Kevin Passmore, "Planting the Tricolor in the Citadels of Communism: Women's Social Action in the Croix de feu and Parti social français," Journal of Modern History 71 (1999): 815. Sean Kennedy contends scholars must not become "preoccupied with categorization." See Reconciling France Against Democracy: The Croix de Feu and Parti Social Français, 1927-1945 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2007), 10. Michel Dobry was the first to criticize scholars' "classificatory approach," in "Février 1934 et la découverte de l'allergie de la société française à la Révolution fasciste," Revue française de sociologie, 30, no. 3/4 (1989): 511-33.

The two works that explore the intersections of women, gender, and the Croix de Feu/PSF are Passmore, "Planting the Tricolor," 815-51, and Mary Jean Green, "Gender, Fascism and the Croix de Feu: the 'women's pages' of Le Flambeau," French Cultural Studies 8 (1997): 229-39.

Robert Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 245.

Archives de la Préfecture de Police, Paris (hereafter APP), B/a 1901: police report, "Section Féminine du Mouvement Social Français des Croix de Feu," 2 June 1936; Archives Nationales de France, Paris (hereafter AN), F7 12964: police report, 11 March 1936.

The data comprising this chart was collated using women's section reports in Le Flambeau issued monthly from March 1934 to February 1935, then weekly from February 1935 to June 1936.

There were twenty-four sections in Algeria, seven in Morocco, and one in Tunisia. This data comes from Le Centre des Archives d'outre-mer (hereafter CAOM), 30 134: Bulletin des Association Croix de Feu du Departément d'Alger, Bulletin de Liaison du Croix de Feu en Algérie; and 91 F 405-406 (Alger) and 93 B3 707, 522, and 323 (Constantine): police reports.

The seven leadership positions within each women's section comprised the following delegates: sewing room; clothing depot; health visitor; social worker; "boys and girls less than 13" (later called Group A); "girls less than 16"; and a male delegate for "boys less than 16" (later called Group B). These positions are explained in AN, 451AP 87 Document 13: report of fall 1935, "Oeuvres sociales Croix de Feu.

AN, 451AP 87: Dossier 62, report of 26 October 1935, "Congrès Général de la Section Féminine du Mouvement Social Français."

AN, 451AP 93: Document 38, circular of October 1935, "Groupe 'A' (Mixte, moins de 13 ans)."

AN, 451AP 93: Document 42, circular of October 1935, "Centres d'Éducation Physique avec Foyer Bibliothèque."

APP, B/a 1902: report of 21 December 1935, General Secretary of the Police Prefecture.

AN, 451AP 87: Document 14, n.d. (probably early 1936), "Rapport sur les Groupes 'A,' 'B,' et 'C.'"

AN, 451AP 93: Document 39, circular of October 1935, "Groupe 'B' Garçons, Moins de 16 ans."

AN, 451AP 87: Document 14, n. d. (probably early 1936), "Rapport sur les Groupes 'A,' 'B,' et 'C.'"

AN, 451AP 87: Dossier 62, Report of 26 October 1935, "Congrès Général de la Section Féminine du Mouvement Social Français."

AN, 451AP 93: Document 39, circular of October 1935, "Groupe 'B' Garçons, Moins de 16 ans."

AN, 451AP 87: Document 5, circular of 10 October 1935, "Le groupe C et les cours de social service."

AN, 451AP 93: Document 40, circular of October 1935 "Le Groupe 'C' et le Foyer des Jeunes Filles.,"

AN, 451AP 87: Document 62, report, n.d. (but probably late 1935) "Action Social de CF: Résumé des Oeuvres Sociales de la Section Féminine du Mouvement Social des Croix de Feu."

For Passmore's discussion of this point, see "Planting the Tricolor," 825.

AN, 451AP 93: Document 42, circular of October 1935, "Centres d'Éducation Physique avec Foyer Bibliothèque."

AN, 451AP 162: Document 5, letter of 1 February 1937 from de Préval to Mademoiselle Ducrocq.

AN, 451AP 87: Document 65, anon., "Rapport sur l'activité du centre de Saint-Ouen," October 1935–June 1936.

AN, 451AP 188: Dossier 3, Work and Leisure report on PSF social centers of October 1936.

AN, 451AP 87: Document 65, Jean D'Orsay, "Rapport sur l'activité du centre de bricolage de Saint-Ouen," 4 April 1936.

AN, 451AP 87: Document 65, anon., "Rapport sur l'activité du centre de Saint-Ouen," October 1935–June 1936.

AN, 451AP 87: Document 65, Jean D'Orsay, "Rapport sur l'activité du centre de bricolage de Saint-Ouen," 4 April 1936.

Green, "Gender, Fascism and the Croix de Feu," 239. Green concluded that women's "reduced status . . . must certainly be seen as a reflection of their evident lack of electoral power."

AN, 451AP 188: Document 9, speech of 1938 by Antoinette de Préval, reprinted in a Work and Leisure General Assembly Report.

AN, 451AP 187: Document 1 (Saint Ouen Dossier), "Relations de 'Travail et Loisirs' avec le 'P.S.F.'" (1937-1938); AN, 451AP 187: Dossier 1, letter of 27 October 1937 from Saint Ouen section president Henry Goubier to Paul Iltis to the President of the St. Denis local committee .

AN, 451AP 184: Dossier 10, newspaper clipping "Correspondance de centre Aubervilliers," L'Écho du Monfort: Bulletin Mensuel des Communistes du Quartier, n.d.

APP, B/a 1952: reports of 18 February 1938 and 28 March 1938 from Le Ministère de l'Interieur to Le Directeur Général de la Sûreté Nationale,.

AN, 451 AP 179: Dossier 2, "Centres 'Travail et Loisir' 1937, 1938, 1939"; report of 23 February 1937, "Reunion des directrices"; and 1AP 171 Dossier 4, report on the center at St. Ouen, n.d., "Centres de Travail et Loisir."

AN, 451AP 171: Dossier 4, Travail et Loisir Centres, report, n.d., "Centre Social Kléber, rue Kléber-Saint Ouen."

AN, 451AP 177: Dossier 2, anon., n.d "Tract Travail et Loisirs."