Dornac's "At Home" Photographs, Relics of French History[*]

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

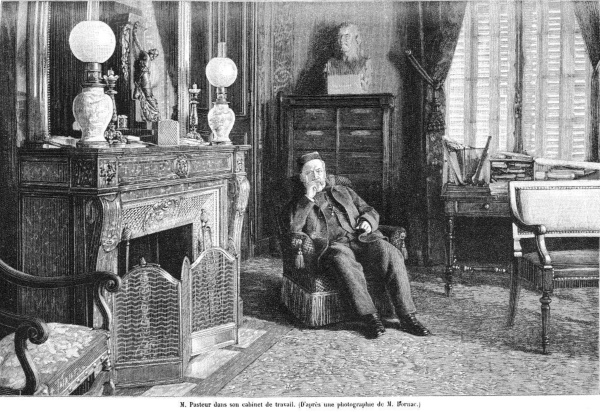

In 1892 the French periodical La Nature began publishing lithographs based on photographs of well-known scientists at home in their studies or at work in their laboratories. Photographs of famous people in their homes or workplaces are commonplace today, but in the 1890s the technique of moving the camera into the home for commercial purposes was innovative, both for its technology (the use of the portable camera) and for its concept. Although photographers themselves took pictures at home, the commercial genre known as "at home" photography was pioneered in France by Dornac (pseudonym of Paul Cardon). Dornac's series, Nos Contemporains chez eux (Our Contemporaries at Home; c. 1887 to 1917), chronicles roughly two hundred leading public figures, among them Sarah Bernhardt, Alexandre Dumas fils, Gustave Eiffel, Gabriel Fauré, President Sadi Carnot, and Louis Pasteur (see Figure 1).[1] Individual photos (measuring 18x15 cm) were on sale through merchants specializing in celebrity photos, while larger and more sumptuous prints (26x20 cm) could be purchased in album form. The innovative series was also republished by the weekly Le Monde Illustré, with accompanying commentary by G. Lenotre (pseudonym of Théodore Gosselin). Lithographs were also reproduced widely in other major illustrated periodicals of the time, including L'Illustration, La Revue encyclopédique, Le Soleil du dimanche, and Les Annales politiques et littéraires. Dornac's invention is credited with having lent its name to the technique of photographing human subjects "chez eux," a movement Alison and Helmut Gernsheim have called "at home" photography.[2]

This essay examines Dornac's "at home" photographs and their implications for the fin-de-siècle cult of celebrity. As the camera began to chronicle the private life of public figures and as editors published these images in the flourishing periodical industry, viewers became aware of the milieu surrounding famous figures.[3] No longer mysterious and untouchable, grands hommes ("great men," though well-known women were also occasionally included under this rubric) began to be treated like scientific specimens on display in their native "habitats." Photography was thus partly responsible for facilitating a shift from interest in grands hommes as revered national heroes, worthy of public monuments, to more intimate and obsessive celebrity cults housed in private rooms, apartments, and museums.

It is not surprising that Dornac's photographs of scientists such as Pasteur (Figure 1) were published in La Nature, a periodical specializing in sciences and their applications for arts and industry, as its subtitle suggests: "Revue des sciences et de leurs applications aux arts et à l'industrie." Yet the four Dornac images that appeared in La Nature (of Pasteur, Marcellin Berthelot, Alphonse Milne-Edwards, and Jules Janssen) served less to elucidate the work of their subjects than to chronicle the importance of the Nos Contemporains chez eux series. Gaston Tissandier, renowned pioneer of hot air balloons, editor of the journal, the author of books about photography, and himself a figure in the Nos Contemporains series, paired the photographs with accompanying texts in which he qualified Dornac's goals as eminently "scientific."[4] Criticizing both the painted and photographic portraits of his time, Tissandier praised the Dornac photographs for their attention to milieu:

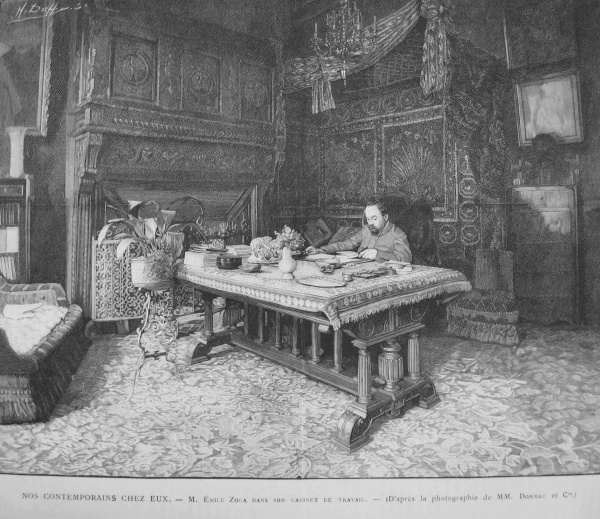

In paintings such as Édouard Manet's well-known Portrait d'Émile Zola, the items surrounding subjects are largely symbolic; they generally do not reflect the reality of the subject's home.[6] Similarly, commercial photographers such as Félix Nadar, Pierre Petit, or Étienne Carjat used props to portray home-like backgrounds. If one looks carefully at Figure 2, a portrait of Zola by Nadar, for example, the canvas roll of the backdrop is visible on the floor and the table reappears in other contemporary Nadar portraits like that of Zola's friend, Edmond de Goncourt. In contrast, Dornac's photographs (reproduced by lithography in Figures 1 and 3) were remarkable for capturing details of his subjects' surroundings, objects Tissandier considered the "witnesses of their thoughts and works":

Viewers today are more savvy about the subjectivity latent in photography, but Tissandier, like many of his peers, overlooked its artifice to represent it is an objective scientific tool. He noted, for example, that Dornac used only natural light, which required a thirty-second pose time, yet did not emphasize the fact that this meant that photographs were necessarily staged.[9] Nor did he comment on the fact that, by reproducing lithographs of these photographs, La Nature's engravers took liberties in copying originals. Instead of mentioning that subjects could have arranged the scene to suit their purposes, he chose to focus on the realism of the items portrayed, interpreting each image in terms of its subject's "familiar attitude" and "milieu." Most surprisingly, given his emphasis on science, Tissandier alluded to Dornac's photographs as relics ("des reliques de l'histoire").[10]

His emphasis on photographs as relics is curious because of the religious register it interjects into his discussion of a development he presents as so solidly scientific, suggesting photography as a new manifestation of the medieval practice of collecting relics—reliquae or remainders—of venerated figures. Yet it is also clear that, while he admired the grands hommes who sat for these photographs, he was less interested in the subjects themselves than in seeing them in a new light, as products of a particular milieu. These images, he believed, would preserve valuable data for the future: "our descendants will surely consult them . . . as relics of history." Tissandier's emphasis on the importance of Dornac's work reveals that he recognized the profound impact visual culture would exert on subsequent generations. Prefiguring Roland Barthes, who describes photography as a "living image of a dead thing," Tissandier's choice of the word "relic" posited photography as a new kind of monument (from monere or reminder) capable of transmitting his present to the future.[11] But before exploring the implications of photographs as monuments, it is important to understand why Tissandier found Dornac's photographs so notable that he devoted four articles to them.

First, Dornac was able to gain access to what had previously been considered the nearly sacrosanct space of the home. Littré, in his dictionary (1863–1872), insisted that private life "should be lived behind walls" and that no one should be able to "peer into a private home or to reveal what goes on inside."[12] Indeed, before the arrival of Dornac's photographs, details about celebrity interiors had been gleaned largely from oral or written sources, through the genre known as the "visite au grand homme,"[13] through memoirs, or later (1880s) through the interview. The studio and carte de visite photographs in wide distribution since the 1850s reproduced likenesses, but they were staged in studios, objects and clothing often borrowed from stock collections. Such celebrity portraits were lucrative since photographers offered free photographs to their subjects in exchange for the ability to sell copies to the public. These copies proliferated around the world.[14] Dornac's large format photos continued this commercial tradition, but instead of reproducing simply a likeness, he represented subjects at home, surrounded by objects and furniture. Perhaps most importantly, using a wide angle lens shifted emphasis from the subject, who filled the frame in carte de visite photographs, to the milieu (Figures 1 and 3). Bringing the journalist and the camera into the living room to "capture reality" allowed the public voyeuristic access to celebrities, thus opening natural environments to viewers in an extraordinarily detailed fashion. Sold in the streets of Paris and reproduced in illustrated periodicals, these photographs became collectors' items.

Second, the serial nature of the enterprise—thirty photos when Tissandier began describing Nos Contemporains chez eux in 1892—was in itself scientific. It was a venture that would allow future historians to compare the decorating and display practices of a brief period across the bourgeois spectrum. This is largely how modern art historians have interpreted Dornac's series.[15] Tissandier, too, was less interested in the aesthetic components of the photographs than in their importance as scientific documents, as a representation of milieu. In fact, he echoed decorating manuals of the time, which posited interior decoration as a direct reflection of the subjects' personality: "In permanent contact with our selves, our interiors are no longer beholden to public expectations; they are purely personal."[16] Journalists, too, spoke of the interior as "the very frame of a man's intellectual and moral portrait,"[17] echoing Edmond Duranty's trademark belief that the figure depicted in a portrait could not be separated from its context.[18]

"Milieu" had become a catchword by the end of the century thanks to the theories of Hippolyte Taine and their further popularization by writers including Émile Zola and Paul Bourget. For Taine, a milieu consisted of the external forces, including politics, socio-economic conditions, or climate, that surrounded and influenced an individual. From displays at the Musée Grévin wax museum, the Natural History Museum in Paris, and the "human zoos" at the Jardin d'Acclimatation, scientific debate about the impact of environment on behavior—both human and animal—was everywhere.[19] Alphonse Milne-Edwards, for example, himself one of Dornac's subjects, mounted an "exposition zoologique, botanique et géologique de Madagascar" in the summer of 1895 at the Jardin des Plantes. Dornac's Nos Contemporains chez eux series was thus timely; the private spaces represented in these images provided a visual summary of their subjects' milieux. Dornac himself stressed this in an autograph: "This Gallery illustrates Taine's theory of milieux and gives interesting ideas about men" (Catalog for Sotheby sale of 15 November 2008, Lot 173). As such, they became valuable documents for drawing conclusions about elements linking "greatness" and environment.

Tissandier's article about Dornac's photograph of Pasteur (Figure 1) does just this, drawing a direct parallel between the objects surrounding the scientist in the photograph and his status as a "great man." He dedicated an entire page to describing each of the items surrounding the scientist and to chronicling their provenance, from the bronze statuette of Jeunesse over the mantel (a gift celebrating his discovery of the anthrax vaccination), to the bust of J.-B. Dumas, Pasteur's teacher, above him (a gift of the sculptor Guillaume). As Tissandier concluded, everything in this apartment was a souvenir of Pasteur's accomplishments, a reminder of the "universal praise and admiration" for his accomplishments.[20] The environment thus reinforced and reflected his public identity as scientist. Similarly, G. Lenotre, in text accompanying each of Dornac's photos in Le Monde Illustré, linked the "desired and picturesque disorder" of actor Mounet-Sully's study to his acting style, while refraining from making "a deep psychological analysis" about the cave ("antre") of critic Francisque Sarcey's dark study.[21]

Tissandier saw objects as having a direct correlation with personality ("the very frame of a man's intellectual and moral portrait"), but such beliefs would soon make way for a more subversive interpretation of the domestic interior based on psychology. Debora Silverman has shown that la nouvelle psychologie (1890) brought widespread public attention to the nervous processes of the mind. As a result, interior decoration as an easily decipherable "frame" gave way to interiors as unstable spaces exerting an imperceptible influence on fragile human minds.[22] Dornac's photographs of "habitats" thus led to increased scientific scrutiny of the ways in which seemingly innocent objects could exert a nefarious influence over their inhabitants. This was particularly problematic for literary and artistic figures; critics tended to interpret paintings or literary works as reflection of the artist and his or her environment (Sarcey's "cave"), instead of evaluating them as independent artistic constructs. This was clear in books like Max Nordau's 1892 Dégénérescence, published in French in 1894, in which the author drew a direct correlation between the clutter of French writers' homes and their melancholy. His work, as well as numerous psychological studies of the time, called into question long-held beliefs about the innate genius of grands hommes, thus shifting discussion from body to environment.

The results of research about genius were published in specialized journals like La Revue philosophique, the Annales médico-psychologiques, or Progrès médical, but they often reappeared in more popular outlets, such as the literary supplement to Le Figaro, Le Temps, or La Revue Illustrée. Readers could thus learn about Émile Zola's sexual fantasies or Alphonse Daudet's dreams and link them to the decor of their homes.[23] Such pseudo-scientific research went even further as scientific techniques applied to criminals were also applied to respected social figures and documented by photography in an attempt to gauge empirically the nature of genius.[24] The most famous of these was Zola's willingness to collaborate with Doctor Édouard Toulouse in 1895 on a barrage of studies to refute alleged correlations between genius and neurosis.[25]

By the late 1890s, thanks largely to the expansion of the periodical press and advances in lithography that made it easier and less costly to print images, the same publications that featured portraits and autographs by leading celebrities—Le Monde Illustré, La Revue encyclopédique, La Revue Illustrée, among others—also published articles about sciences related to the interpretation of such images, the study of facial characteristics (physiognomy), the analysis of handwriting (graphology), the reading of palms (chiromancy), or the analysis of bodily measurements (anthropometry), for example. Although such scientific observation was most often applied to the growing field of criminology, articles in the periodical press also scrutinized leading public figures. As a result, readers could become armchair scientists, applying their "scientific knowledge" to their favorite celebrities, whose images, autographs, palms, and fingerprints could be broken down in order to discover the "real" personality underlying the public persona. Both living and dead, celebrities were objectified: images of their bodies and graphs of their bodily processes were reproduced and published in widespread circulation; they were subjected to all manners of pseudo-scientific analysis.

If Tissandier was captivated by Dornac's "at home" photographs, it was above all because they arrived at a moment of visually based scientific exploration where grands hommes became less interesting to the public for their accepted greatness—their works—than for the elements understood to have contributed to that greatness—their spirit, influenced by their environment. By opening celebrity lives to public scrutiny in ways that memoirs, interviews, and studio photographs had not, Dornac provided the kinds of visual data about the milieu of the celebrities that scientists and the public had been seeking. While Tissandier clearly respected the grands hommes he discussed in the early 1890s, by the end of the decade their social status had changed markedly. With the multiplication of images in circulation after the explosion of the illustrated periodical press in 1881, their private lives were no longer considered off limits. Henri Coupin pointed this out in 1897:

Images of celebrity bodies and homes were increasingly available for consumption—their photographs and autographs collected or used to sell a variety of products from chocolate to wine to cigars (with or without their permission)—and for "dissection"—their possessions, fingerprints, measurements, and palms analyzed at will. Perversely, Dornac's Nos Contemporains chez eux—the very series that sought to reinforce celebrity by commemorating it ––transformed the grands hommes of the fin- de-siècle into naturalistic specimens of humanity, their "habitats" open to public analysis.

Yet while these photographs contributed to turning grands hommes into scientific subjects, they also helped commemorate their achievements. The work of writers such as Edmond de Goncourt, who presented interior decoration as a creative act in his 1881 La maison d'un artiste, is confirmed by Dornac's photographs. After his death, Goncourt's extensive collections were sold at auction to finance the Prix Goncourt. Though the collections no longer exist today, they do live on in the text of La maison d'un artiste and in numerous photographs, Dornac's shots of Edmond in his study and "Grenier" among them. Both Goncourt and Dornac took part in a wave of interest in the aesthetic potential of the domestic interior that swept the 1880s and 1890s. Symbolist poets and artists advocated "subjectifying the objective," understanding interior decorating as an extension of their art, or they experimented with designing interiors to express character.[27] Yet others, such as Gustave Moreau and Ferdinand Khnopff, so considered their homes extensions of their creative work that they preserved them for posterity. All of these movements gave further impetus to the French public's appreciation of the interior as a projection of their identity.

The early nineteenth-century ideal of a "monument in stone," an authorized image of the "great man" erected in a public space to commemorate his cultural importance, thus gave way, as we have seen, to much more fragmented and complex images, often disseminated by photographs, by which the public sought to understand famous figures more fully.[28] Leo Braudy has pointed out that celebrity photographs were particularly successful because "the silence of the photography allowed a combination of distance and intimacy . . . By turning human beings into objects of silent contemplation by themselves and others, it embodied the possibility that spiritual virtue might be made visible if properly posed and properly perceived."[29] Dornac's "at home" photographs went a step further, creating the illusion of even greater intimacy by providing access to the environment in which grands hommes lived and worked. By shifting emphasis from physical appearance to milieu, his series allowed viewers to vest the objects surrounding his famous subjects with near-magical powers: as "relics," they seemed to retain some of the spirit of those who had touched them.

Such value accorded to celebrity interiors led to the development of one of the twentieth century's most popular commemorative activities: the establishment of celebrity house museums. Immediately following a celebrity's death or even years later, objects and furnishings (including photographs) were gathered in a central repository, often a former home, in an attempt to provide a much more complex understanding of the subject than would a mere tombstone or statue. The first official house museums in France—the Musée Gustave Moreau and la Maison Victor Hugo—both opened in 1903.[30] Public reception of Hugo's former home on the Place des Vosges was overwhelming, and journalists waxed lyrical about this unique opportunity to commune with the author's spirit and works. Indeed, visitors such as Jules Claretie placed the house in direct opposition to his mortuary monument: "[In the house] he is more present in the intimacy of his life than in his coffin, under the vault where he lies . . . here . . . his heart beats and his immortality shines forth."[31]

Though statues continued to be erected well into the twentieth century, it was photographs and particularly "at home" photographs that, while fragmenting identity during celebrities' lifetimes, took on a more intimate commemorative function after death. Dornac's photographs have continued to play a specific role in this movement: "relics of history," as Tissandier called them, the photographs of Nos Contemporains chez eux have allowed curators to shape authentic or imagined domestic interiors. Although Dornac is barely known by name today (it is rare to find his name among lists of active nineteenth-century photographers), Tissandier was correct in anticipating the documentary value of his series: they are among the most recognizable photographs of fin-de-siècle notables and figure prominently in anthologies and textbooks, and on the Internet today. Dornac's emphasis on documenting milieu has allowed each new generation to construct living monuments that perpetuate the spirit of the grands hommes of the past through proximity to their familiar objects and surroundings, the "witnesses of their thoughts and words."

- *

Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

For more information about the series and a wealth of reproductions, see the 2008 catalog compiled by Piasa before the 16 May 2008 auction of Paul Cardon's personal prints. Marie Mallard lists many of the copies housed in French archives in her MA thesis, "Étude de la série de Dornac: nos contemporains chez eux, 1887–1917: personnalités et espaces en représentation" (Paris IV, 1999).

Gaston Tissandier identified him as the creator of this genre in articles for La Nature as did an anonymous reporter in an 18 December 1897 article for L'Illustration (510-11). For more about "at home" photography in England and France, see Gernsheim, A Concise History, 129-39; on commercial photography in the nineteenth century, see Elizabeth Anne McCauley, Industrial Madness: Commercial Photographs in Paris, 1848–1871 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), Donald E. English, Political Uses of Photography in the Third French Republic 1871–1914 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Publications in Photography, 1984), and Michel Frizot, ed., A New History of Photography (Köln: Könemann, 1998).

By "milieu," I refer both to the dictionary sense of environment, but also to the more scientific sense attributed to the word by Hippolyte Taine and Émile Zola. For Taine's most comprehensive discussion of "milieu," see Histoire de la littérature anglaise, 3 vols. (Paris, 1863).

The four articles in which Tissandier discussed Dornac's series are: "Nos savants chez eux: M. Pasteur" (1892), 168-70; "Photographies de nos contemporains chez eux" (1894), 280-82; "Photographies de nos contemporains chez eux: M. A. Milne-Edwards" (1895), 40-42 ; and "Photographies de nos contemporains chez eux: M. Janssen" (1895), 329-31. At first, these articles dwell primarily on Dornac, but they progressively illustrate Tissandier's points about accomplishments and milieu, as in the case of Janssen.

Tissandier, "Photographies de nos contemporains chez eux" (1894), 282. Tissandier treats studio photography in "Nos savants chez eux," 168. Unless otherwise indicated all translations from the French are mine.

On Manet's portrait, see Maya Balakirsky Katz, "Photography Versus Caricature: 'Footnotes' on Manet's Zola and Zola's Manet," Nineteenth-Century French Studies 34, no. 3-4 (2006): 323-27.

Tissandier, "Photographies de nos contemporains chez eux" (31 March 1894), 282.

Tissandier, "Nos savants," 170, describes the process thus: "[A]ssisted by a skilled cameraman (opérateur), equipped with a wide-angle lens and a large-format chamber, he takes portraits of our celebrities in their study or sitting room; not by flash photography (à la lumière du magnésium), but in plain daylight, thanks to a long pose of about thirty seconds."

Roland Barthes, La chambre claire (Paris: Seuil, 1980), 123.

Cited by Michelle Perrot, "At Home," in A History of Private Life. From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War, ed. Michelle Perrot, trans. by Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 348-58, 341.

See Olivier Nora, "La Visite au grand écrivain," in Pierre Nora, ed., Les lieux de mémoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), 2:2131-56.

See English, Political Uses, 3-6, and Frizot, "Distinguished personnages," in A New History of Photography, 123.

See, for example, Valerie Mendelson, "A Citadel Behind Walls: The House of the Amateur in Late Nineteenth-Century France" (Ph.D. Thesis, CUNY, 2004) or Marie Mallard, "Étude de la série de Dornac."

Henry Havard, L'art dans la maison (La grammaire de l'ameublement) (Paris, 1884).

Anonymous, La Caricature, 11 March 1882, reprinted from La Vie élégante.

See Robert Nye, Crime, Madness, and Politics in Modern France: The Medical Concept of National Decline (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984) and Pascal Blanchard et al., eds., Human Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age of Empire (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008).

G. Lenotre, "Les Contemporains chez eux: M. Mounet-Sully," Le Monde Illustré 65 (28 December 1889): 395-96; "Les Contemporains chez eux: M. Francique Sarcey," Le Monde Illustré 66 (18 January 1890): 51-52.

Debora Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-siècle France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 75.

See Jacqueline Carroy, "Premières enquêtes psychologiques françaises: L'introspection, l'individu et le nombre," Mil neuf cent 22 (2004): 59-75 and "'Comment fonctionne mon cerveau?' Projets d'introspection scientifique au XIXe siècle," in J.-F. Chiantaretto, ed., Écriture de soi, écriture de l'histoire (Paris: In Press, 1997), 161-79.

Dobelbower, for example, has argued that the enthusiastic international reception accorded Lombroso's Criminal Man stemmed in great part from his exploitation of visual images. Nicholas Dobelbower, "The Arts and Science of Criminal Man in Fin-de-Siècle France," Proceedings of the Western Society for French History 34 (2006): 205-16.

See Jacqueline Carroy, "'Mon cerveau est comme dans un crâne de verre': Émile Zola sujet d'Édouard Toulouse," Revue d'histoire du XIXe siècle, 20/21 (2000). This study led to re-interpretation of the data by others, including Lombroso and Nordau.

Henri Coupin, "Photographie moderne," 511. The English and italics are in the French original.

See Gustave Kahn, "Réponse des symbolistes," L'Événement, 28 September 1886. Sharon Hirsch discusses the importance of interiors for the Symbolist aesthetic in Symbolism and Modern Urban Society (Cambridge University Press, 2004). Heather McPherson explores the tensions between photography and portrait painting in The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Michael Garval traces this movement and revisits the issue of "la statuomanie" in A Dream of Stone: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2004).

The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and its History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 492.

Gustave Moreau's house opened first, but was overshadowed by Hugo's. See Elizabeth Gray Buck's work on Moreau, including "Museum Authority and Performance: The Musée Gustave Moreau," in Della Pollock, ed., Exceptional Spaces: Essays in Performance History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 294-316.

Jules Claretie, La maison de Victor Hugo Place royale (Paris: Éditions d'art Edouard Pelletan, 1904).