Shared Sacrifice and the Return of the French Deportees in 1945

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In the years following World War II the divisiveness that seemed prevalent in France before and during the war appeared to have dissipated. One factor which helped France unite was a shared understanding of the recent past. Whatever differences existed in France before the war, the French took pride and comfort in remembering their nation's long and united struggle against foreign occupation and the shameful policy of collaboration. This vision of the recent past promoted unity and national pride after the war, but it also came at a cost. Many French citizens who had suffered disproportionately during the war were forced to set aside their grievances and hopes of compensation so as not to fragment this national unity. One group that bore this cost was the two million French citizens who had been held in Germany against their will during the war and who were only able to return home following the collapse of the German Reich in the spring of 1945.

The period of French history from the liberation of Paris until the end of World War II is normally, and correctly, seen as a time of celebration. Historians who study this time period also recognize that it was dominated by severe material shortages. In many ways the economic deprivations suffered by the French during the first months of liberation were actually harsher than during the German occupation.[1] The celebratory atmosphere was also tempered by at least two waves of retributive French-on-French violence during which thousands of summary executions and organized assaults were carried out.[2] France was free again, but it was also economically devastated and temporarily forced to accept a compromised form of legality and order.

In an attempt to minimize disruption and foster national unity the French provisional government and Charles de Gaulle promoted a vision of France united in resistance during World War II which has come to be known as the Gaullist myth. The notion of shared sacrifice was a key element of the Gaullist myth. Shared sacrifice promoted the vision that almost all French people had quickly sided with the forces of resistance and only a small faction of French society had accepted collaboration. This vision defined the true France as the vast majority of the people who remained loyal to their national and republican principles. Opposing this France was a small number of criminals and traitors who hijacked the government and made common cause with the Germans. Vichy was not France; the Resistance was. Because this vision of shared sacrifice defined almost everyone as part of the Resistance, occupied France was not a nation of a few heroes and a few villains but one united in a struggle against foreign occupiers and a small cabal of traitors.

Acting in a manner consistent with this vision of shared sacrifice required the government to prevent large numbers of people from being labeled either heroes or traitors. It required limited definitions of what constituted punishable collaboration and exceptional heroism. The armed Resistance was the only group that the provisional government singled out for elevated honor, and individuals seeking that recognition had to prove that they were an active member of a acknowledged militant resistance movement prior to the Normandy landings.[3]

Shared sacrifice was an agreeable vision to most French citizens as it allowed practically all of them to identify themselves as part of the Resistance, if only in heart and mind rather than through perilous action. Historians have, in fact, demonstrated that French public opinion during the occupation was generally, if passively, pro-Resistance. Shared sacrifice defined resistance broadly and thereby aided the French in identifying themselves as a nation long united in a common undertaking. This liberal definition of resistance left space for those small segments of the population who occupied the opposing extremes to be defined as either heroes or traitors. To broaden the definition of Resistance hero or collaborationist traitor would disrupt the unifying vision. Like so much else in liberation era France, elevated honor and criminal culpability had to be tightly rationed in the service of national revival.

Approximately two million French deportees returned to this setting in April and May 1945. They were not a homogenous group. Roughly half of them were prisoners of war: men who had been captured in 1940 and who had spent the last five years in Germany as forced laborers. The second largest group was that of the labor deportees, most of whom the Vichy government had drafted for obligatory national service in Germany. The final portion was made up of French citizens who had been deported to Germany and placed in either concentration or extermination camps due to their Jewish ancestry or as punishment for suspected resistance activity.[4]

Members of these four groups did not see themselves as unified by their experience of captivity, and each group had representatives who attempted to differentiate their experiences from those of others. Categories of prisoners had been taken to Germany for different reasons, and while in captivity each was treated differently. The prisoners of war had been incarcerated since 1940 while most of the political deportees had been held for less than one year. In almost all cases Jewish deportees were murdered; only three percent of the racial deportees, as the French referred to them, survived the ordeal. The discrepancy between the ninety-seven percent mortality rate suffered by Jewish deportees and the less than two percent mortality rate of the prisoners of war and workers calls into question any simplistic correlation of their experiences.

French citizens distinguished between groups of returning deportees and treated the returnees differently upon their liberation. The political and racial deportees were regarded as national symbols of suffering under Nazi barbarity and extended unconditional compassion. The prisoners of war were warmly welcomed home as victims but very often not as normal veterans. As Megan Koreman has argued, on the local level the return may have been "the most important event of a full and momentous year," but on the national level the government did not enact policies to help the former prisoners quickly reintegrate into national life. One striking example of this discrepancy was the government's refusal to delay municipal elections in April 1945 to allow more returning prisoners and deportees to participate.[5] The French provisional government also encouraged citizens to receive the returning workers as unfortunate victims, but the laborers were often treated with scorn and, in some instances, with the same violence that was directed towards collaborators.

Despite the obvious differences between the groups of returnees and the evidence that the French people were separating the returnees into different groups, the provisional government enacted a policy of providing all services for the returnees through one newly created office, the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees, and Refugees (MPDR). The repatriation plan that the ministry developed and enacted consciously treated all returnees in essentially the same manner and orchestrated a public information campaign encouraging the public to see them as a homogeneous group.

The MPDR repatriation plan called for all returnees to be processed in a similar fashion. Both in its public pronouncements and internal correspondence the MPDR treated the returnees as unfortunate victims deserving of compassion but not as individuals due special recognition or long-term government benefits. A December 1944 release that the MPDR prepared for Temps Présent expressed this policy, stressing that the ministry was working to provide aide to all deportees still in Germany. So far, however, "[o]nly the prisoners have benefited from effective state aid. The workers are roughing it out; the political internees have been abandoned by all but the French Red Cross. It is necessary to guarantee all deportees equal aid from the government in the future."[6]

The MPDR calculated that in most cases the returnees would require roughly seventy minutes of individual attention during which time they would be processed and given a superficial health check-up.[7] After this screening the returnees were provided with, or in some cases allowed to retain, a modest amount of money. They were given a coach class train ticket to their home and an address for a local Maison du prisonnier. These maisons were group homes where returnees could rest and eat for a few days at state expense before returning to their own homes. The unrealistic nature of this repatriation plan was immediately apparent when the MPDR welcome stations were overrun by deportees arriving on their own schedule, not in the more orderly fashion the plan had envisioned. The welcome stations and maisons informed the MPDR as early as March 1945 that a higher percentage of the returnees were suffering from physical and mental health problems than they were equipped to address. While some reports described the returnees as in satisfactory health, others described their state as "very disturbing," noting that many suffered from a "certain depression" and were in need of immediate additional financial assistance.[8] A visible symbol of the plan's shortcomings that newspapers found easy to dramatize was the fact that in most cases the returning deportees were not even provided with a fresh set of clothes before being placed on a homebound train. Somehow the MPDR had overlooked the humiliation returning deportees would feel as they spent their first few days of freedom traveling across France wearing the tattered remains of their striped prison uniforms.[9]

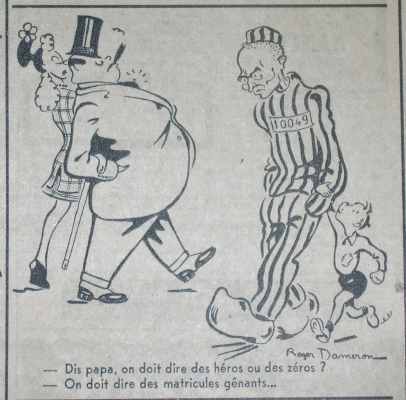

This June 1945 editorial cartoon speaks not only to the national shame of not properly providing for returning deportees but also to the frustration felt by many regarding disparity in levels of wartime sacrifice. The son asks the father, "Dad, how can you tell the difference between 'heroes' and 'zeroes'?" as both words sound similar. The father replies that one could look for the serial numbers, referring to the tattered uniform he still is wearing. Source: La France au Combat, 28 June 1945, 6

This June 1945 editorial cartoon speaks not only to the national shame of not properly providing for returning deportees but also to the frustration felt by many regarding disparity in levels of wartime sacrifice. The son asks the father, "Dad, how can you tell the difference between 'heroes' and 'zeroes'?" as both words sound similar. The father replies that one could look for the serial numbers, referring to the tattered uniform he still is wearing. Source: La France au Combat, 28 June 1945, 6Many returnees, perhaps most, found the homecoming experience disappointing. It did not live up to their long cherished dreams, and it did not rise to a level commensurate with the sacrifice they believed they had made. The liberated prisoners perhaps felt this initial disappointment most strongly. The POWs had spent five years envisioning their homecoming as a time of national celebration. Vichy government propaganda had assured them throughout the first years of their captivity that upon their return they would assume a prominent place in the national rebuilding effort: they would be a purified vanguard that would lead the French people in the revitalization of their nation.[10] Instead, the prisoners generally found themselves warmly welcomed home by their families and local communities but not deferred to on the national level. The prisoners were not objects of national pride or honor; members of the resistance movements had filled that role. Most prisoners were less familiar than their countrymen with these resistance fighters, as their captivity had isolated them from the internal struggle. Perhaps the most unwelcome surprise for the prisoners was the provisional government's decision to demobilize them immediately upon their liberation and not to recognize them as combat veterans. Not only did this denial of their military status strip the liberated prisoners of a position of high honor in French society, something they undoubtedly had assumed as their right, it also deprived them of extensive social and financial benefits. Stripped of an identity and support system they had believed to be theirs by right, the ex-prisoners of war found themselves thrust into a radically transformed nation deeply mired in economic depression. Clearly this was far from an ideal setting for these men to reconstruct their lives and regain their physical and mental health.

Most historians studying the return of prisoners to France have addressed the shortcomings of the repatriation as an example of either callous indifference or incompetent planning. They have focused on the administration of the ministry and, in particular, on its head, Henri Freney.[11] Freney provided an easy target due to his inflexible and authoritarian manner as well as his emotional and defensive reaction to any criticism. Aiming a critique of the repatriation at Frenay and the MPDR does highlight some of the administration's obvious shortcomings. However, historians should place the repatriation plan within its larger context, the national dialogue of shared sacrifice. In this context, the repatriation appears as a sad by-product of the reconstruction, not simply as a bungled effort. The return of prisoners was orchestrated to promote compassion, unity, and an efficient transfer of the deportees out of the public sphere and back into civilian life. Its administrators discouraged the returnees from expecting any public aid after the initial few days and labeled their attempts to work for group recognition as divisive and selfish.

The postwar government attempted to offer uniform treatment to the different groups of returnees and put all categories of prisoner under one ministry as part of its effort to unify and rebuild France. As unfortunate French citizens suffering from a long ordeal, returning prisoners all deserved compassion and short term assistance – but no more. The repatriation plan welcomed home the two million returning deportees but discouraged them from asserting greater claims on national honor because such deportees' claims could splinter the carefully fostered unity of shared sacrifice.

Perhaps the decision to treat all deportees identically also had a more immediate and concrete motive: the scarcity of resources available to the French government in 1945. Uniform treatment in reality meant treating all the deportees as unfortunate refugees. When the repatriation plans were drafted in 1943 and 1944, dealing with the deportees as refugees may have seemed reasonable in regard to the workers and, before the nature of the German camp system was understood, also for the political and racial deportees. After all, there was no historical precedent for untangling massive deportations on the scale that the Holocaust and the German slave labor system produced. Given what was known at the time, the decision to treat racial and political deportees in the same manner as forced labor deportees is understandable. Treating prisoners of war in the same manner as civilian deportees is harder to understand. Historical and cultural precedent in France dictated that veterans were a group entitled to honor and attention. The decision to treat all groups the same effectively stripped the prisoners of war of an elevated status. Why would the government pursue this course? Two motives quickly come to mind: judgment and resources. The government had judged the prisoners and found that they did not deserve the same honorary status as other veterans. This was a convenient decision because, quite simply, the state was starved for resources and could ill afford to take on a million more young men as dependents.

Stripped of benefits, pensions, and the honor of being recognized as veterans, returning prisoners of war saw shared sacrifice as more accurately meaning continued sacrifice. Almost immediately groups of ex-prisoners challenged their treatment. These challenges took the form of public questioning of the MPDR's competence and of street protests, the first of which occurred in Paris on 18 May 1945. Several hundred ex-prisoners protested against what they described as an ineffective and unresponsive ministry which was negligent in its responsibility to ensure that the prisoners were receiving proper health care.[12]

Several factors allowed the prisoners of war to mobilize a rapid political challenge to their treatment while other groups remained less outspoken. The most important of these factors was that, unlike the other groups, the prisoners could channel their challenge through pre-existing organizations. They did not need to organize upon arrival; they simply needed to join already established ex-prisoner of war groups. The most active of these was the Mouvement National des Prisonniers de Guerre et Déportés (the MNPGD), which had been formed during the war by merging the two largest ex-prisoner of war resistance groups. The MNPGD also provided the prisoners with a very capable and effective spokesman, himself a young and handsome ex-prisoner of war, François Mitterand. Few will be surprised to learn that Mitterrand harbored political ambitions in 1945. He saw the returning prisoners as a constituency which he could transform into a political movement, and he began to define his political identity by championing their cause against the political breakwater that was Frenay.[13] Finally, the prisoners of war could also tap into the French tradition of respect for veterans. Few nations had institutionalized the practical veneration of veterans as much as the French, and this culture of honoring veterans was perhaps at its peak during the interwar and Vichy years. By mobilizing these factors – organization, leadership, and public support – the prisoners of war were slowly able to make inroads into repatriation era policies. While the ex-prisoners of war never gained full equality with other veterans, by 1954 they had won enough concessions from the government that their situations were nearly equal.[14]

Of the four returnee groups, only the prisoners of war successfully challenged the idea of shared sacrifice during the immediate post-war years. This struggle for recognition and benefits can be seen as a case study of dissention in post-war France and an illustration of one of the key paradoxes of the concept of shared sacrifice. Shared sacrifice promoted unity in France by allowing almost all French citizens to invoke a common sacrifice while at the same time preventing most of those who had borne greater hardship from drawing attention to this fact. Not until the 1970s were the racial deportees, in particular the Jewish deportees, able to break down the repatriation's false assertions of uniformity and call attention to the particularly tragic nature of the Shoah. The Holocaust memorial in Paris is literally a concrete reminder of this late recognition that the deportation targeted certain groups with barbaric severity. Unlike most Holocaust memorials, the French memorial merges the Jewish experience with that of all victims of the deportation, without explaining that while many groups were deported and suffered, not all deportations were the same. More recently still the former labor deportees have organized to tell their story and gain recognition and reparations for their own losses.

The vision of France as united in purpose and sacrifice during the war did help carry the nation quickly through a period of hardship, and perhaps it also helped prevent the chaos that many had feared in 1944 and 1945. However, this unity and order came at a cost, which those French citizens who had lost the most to the war bore disproportionately.

For France's post-Liberation economic difficulties, see Tyler E. Stovall, France since the Second World War (New York: Longman, 2002), 12-3; and Maurice Larkin, France since the Popular Front: Government and People 1936-1986 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 117.

Peter Novick, The Resistance versus Vichy: The Purge of Collaborators in Liberated France (London: Chatto & Windus, 1968), 202-14; and Fabrice Virgili, Shorn Women: Gender and Punishment in Liberation France, trans. John Flower (New York: Berg, 2002), 113-9.

Pieter Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation: Patriotic Memory and National Recovery in Western Europe, 1945-1965 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 38-47.

Ministère des Prisonniers, Déportés et Réfugiés [hereafter MPDR], Bilan d'un effort (Paris, 1945), 5-10; and Annette Wieviorka, Déportation et génocide. Entre la mémoire et l'oubli (Paris: Plon, 1992), 21.

Megan Koreman, "A Hero's Homecoming: The Return of the Deportees to France, 1945," Journal of Contemporary History 32 (1997): 9, 14.

"L'aide matérielle, intellectuelle et morale aux prisonniers de guerre, aux internés politiques et aux travailleurs déportés en Allemagne," 5 Dec. 1944, attributed to Génèral Codechèvre and M. Richard. Archives Nationales, Paris, [hereafter AN] Fond 9, Box 3168, Folder Courrier arrivé Dec. 1944–Dec. 1945.

Henri Frenay, The Night Will End, trans. Dan Hofstadter (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973), 340.

Christophe Lewin, Le Retour des prisonniers de guerre français (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1986), 67-70, 82-7; and AN, Fond 9, Box 3243, Folder Extraits des rapports des directions départementales. This file contains a collection of departmental MPDR director reports which survey of the state of the liberated deportees' health during Mar.–July 1945.

Sarah Fishman, "Grand Delusions: The Unintended Consequences of Vichy France's Prisoner of War Propaganda," Journal of Contemporary History 26 (1991): 229-54.

See Lewin; François Cochet, Les Exclus de la victoire, Histoire des prisonniers de guerre, déportés et S. T. O. (1945-1985) (Paris: S. P. M., 1992); François de Lannoy, Un Million de prisonniers de guerre français, Mai 1945; La libération des camps (Bayeux: Heimdal, 1995); Yves Durand, La Captivité: histoire des prisonniers de guerre français 1939-1945, 2nd ed. (Paris: Fédération Nationale des Combattants Prisonniers de Guerre et Combattants d'Algérie, Tunisie, Maroc, 1981), 511-36; the primary accounts left by Frenay; François Mitterrand, Leçons de choses de la captivité (Paris: Les grandes éditions françaises, 1947); and idem, Les Prisonniers de guerre devant la politique (Paris: Editions du Rond-Point, 1945).

"Manifestations de prisonniers rapatriés," Le Monde, 19 May 1945; and "Le grave problème du rapatriement des prisonniers et déportés," Franc-Tireur, 16 May 1945.

A program Mitterand sketched out in Les Prisonniers de guerre.

Lewin and Cochet both provide good accounts of the long post-war effort by the ex-prisoners to gain veteran benefits.