First Things First: Exploring Maslow’s Hierarchy as a Service Prioritization Framework

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

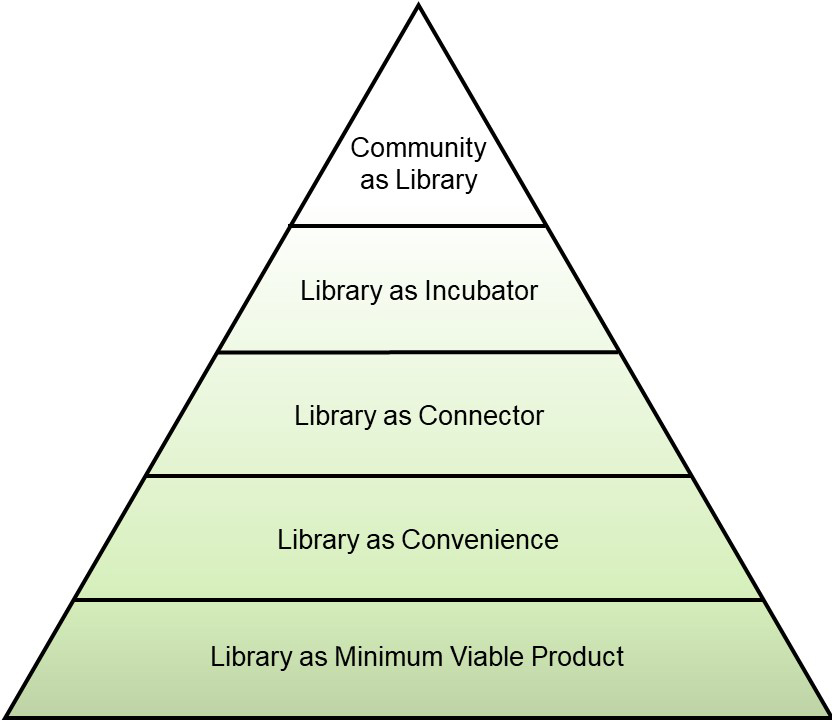

This paper proposes a model for categorizing library services and resources by their importance to users based on the service’s fundamentality to the other resources and services in the library’s offerings, the degree to which the service affects users, and the scope of users that access the service. Adapted from Abraham Maslow’s theory of motivation, we substitute individual human motivations for a community’s motivations for using the library. Maslow’s five tiers—physiological needs, safety needs, love and belongingness needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization—are changed to library-specific tiers: Library as Minimum Viable Product, Library as Convenience, Library as Connector, Library as Incubator, and Community as Library. The Hierarchy of Library User Needs is a theoretical tool for service prioritization with the potential to facilitate discussions between users and libraries. Libraries may wish to (re)evaluate the alignment between the resources they devote to their services and the items that are most likely to be used and appreciated by their users.

Introduction

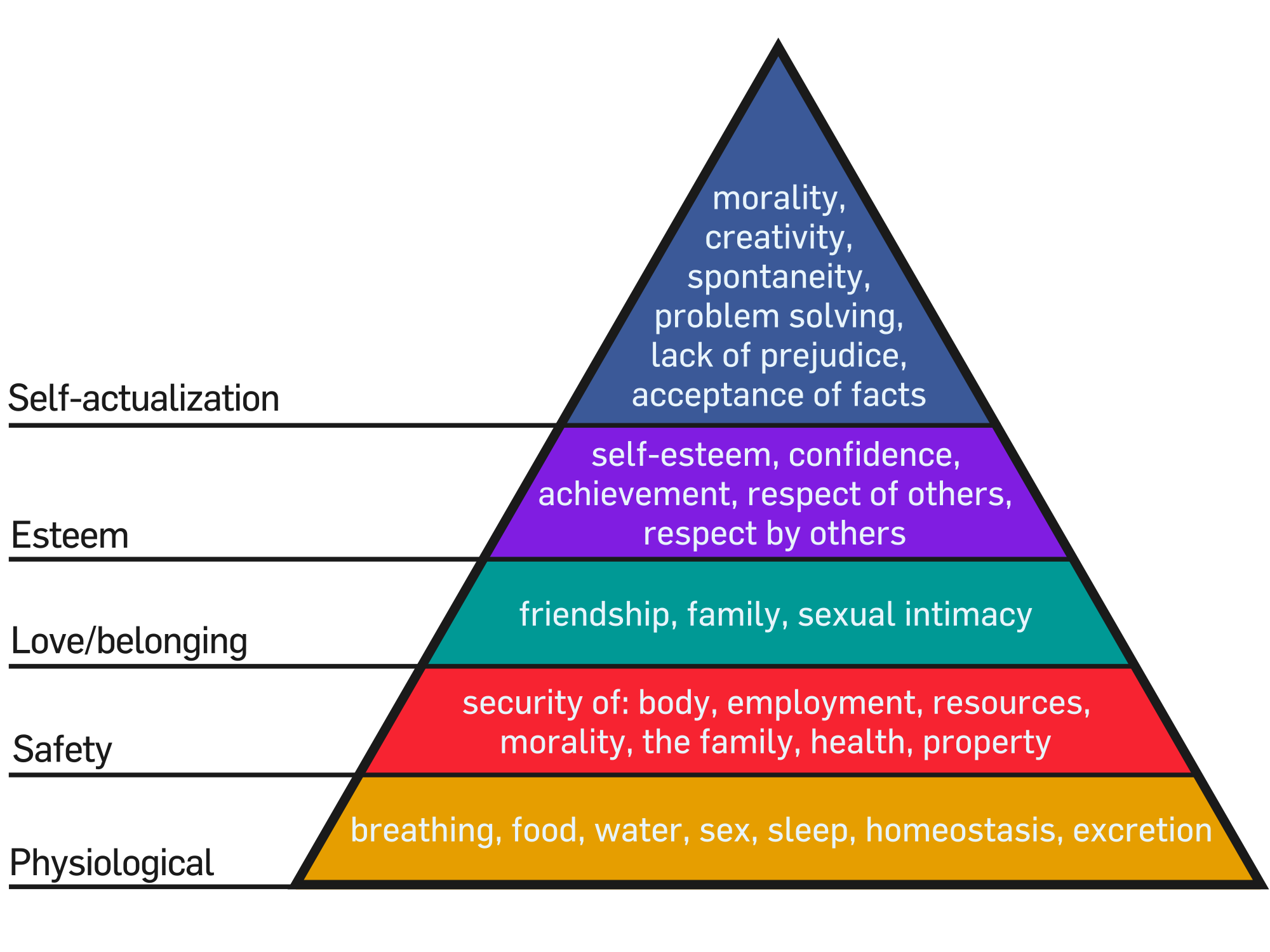

Know Your Meme (Downer, 2017) traces a humorous version of Maslow’s theory of human motivation, commonly called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, to 2014. In this version, someone has drawn another row underneath the pyramid and written “Wi-Fi” in the new space (see fig. 1). This meme uses hyperbole to make light of the perception that wireless internet has become a basic need for many people, though perhaps not quite as basic as food, water, and shelter. The red “Wi-Fi” text appears unprofessional and untidy when contrasted with Maslow’s standard pyramid in typed, black text above it, reminiscent of the way an adolescent might use a sharpie to deface a poster or billboard. This dichotomy suggests that the ways experts interpret motivation may now be different from how everyday people perceive their lived reality. The differential between how institutions and individuals perceive motivation is also at the crux of user experience (UX) work in libraries. Much of the research and user testing we do is designed to surface gaps between what is important to our users and what we deliver them.

Deciding how to allocate resources requires weighing a wide variety of needs against one another making it difficult to satisfy everyone. This is a universal challenge for library administrators, as budgets are finite. Furthermore, libraries exist within funding systems where they are usually “competing” with other worthy organizations or departments for funds. This leaves libraries with the job of ensuring that their services are meeting user needs, while also working to dazzle their funders and show that they are helping them accomplish their wider missions. This can be challenging to get right. If libraries put too many resources into the basics, users will be well served, but funders may perceive libraries as wanting more and more money to maintain an uninspiring status quo. Focusing too much on refining the basics may also cause libraries to miss crucial opportunities to innovate or address emerging user needs. If libraries allocate too many resources to high-level or niche services, this will leave the basics without the care and attention that they need. The basics are the most widely used library services, and failure to invest in them may leave the average user feeling unsatisfied with library services.

This paper proposes a Hierarchy of Library User Needs based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. As applied to library services, Maslow’s five tiers become (1) Library as Minimum Viable Product, (2) Library as Convenience, (3) Library as Connector, (4) Library as Incubator, and (5) Community as Library. We suggest placing library services and resources in each tier according to how fundamental they are, the degree to which users are affected by them, and the scope of users in the community who access them following Maslow’s ordering of needs from most basic to most sophisticated.

This model articulates a UX approach to service prioritization. It is theoretical and has not yet been used in practice. As each library has a unique user community, each library will have different resources and services in each tier. In order to apply the model in a real library setting, it must be used in tandem with user research. UX is founded on the idea that practitioners should not make decisions about what users need without talking to them. We offer this model in hopes that it can be helpful for both UX professionals and library administrators to explore the challenging work of prioritizing user needs within a suite of library services.

Literature Review

A Maslow Refresher

Abraham Maslow’s theory of motivation, commonly called the “Hierarchy of Needs,” will be familiar to many (see fig. 2). It seeks to explain human behavior as deriving from a set of needs that we all share as mortal beings:

- The physiological needs include the need for air, water, food, and anything a human body must have to continue living.

- The safety needs require familiarity, order, and stability. War, violence, natural disasters, and oppression would all threaten the safety needs.

- Humans next seek to satisfy their belongingness and love needs. We need warm, affectionate relationships, both platonic and romantic.

- The esteem needs have us seeking recognition, status, and respect from others.

- Maslow’s definition of self-actualization is somewhat fuzzy: “the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of being” (Maslow, 1943, p. 382). Anything that gives an individual a sense of purpose and fulfillment, of becoming their best selves, would count as self-actualization. Things in this category could include artistic expression, athletic achievement, and social or political activism.

These needs are organized in order of what Maslow calls “prepotency” meaning that “the appearance of one need usually rests on the prior satisfaction of another, more prepotent need” (1943, p. 370). For example, a person in immediate danger of dying may take risks to their safety that would be unacceptable in other circumstances, just as a person in the midst of a natural disaster is unlikely to consider their dating life a priority in that moment. Maslow insists that people are motivated by multiple needs at once (1954). Emotional eating satisfies both the physiological and the belongingness and love needs, just as competing at a high level in your chosen sport may satisfy your need for esteem and for self-actualization.

All needs are always in a state of partial satisfaction. Maslow asserts that as we ascend the “hierarchy of prepotency,” the needs are less satisfied (1954, p. 100). When a lower need is very unsatisfied, then, the higher needs become less motivating to the individual. Imagine attending a meeting if you were hungry. At the beginning of the meeting, your hunger might be minor and not an impediment to paying attention or participating. As the meeting drags on past lunchtime, however, your hunger becomes a more pressing concern that intrudes on your attention span, patience, and contribution effectiveness.

Maslow’s theory remains a theory; it has never been adequately validated. Soper, Milford, and Rosenthal (1995) and Wahba and Bridwell (1976) conducted literature reviews of the empirical evidence and concluded that they were insufficient to justify the theory’s popularity. Others have tried to update the theory. Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg, and Schaller (2010) promised a “renovated” model that accounts for advances in evolutionary biology, anthropology, and psychology with seven overlapping “goal systems”:

- Immediate physiological needs

- Self-protection

- Affiliation

- Status/esteem

- Mate acquisition

- Mate retention

- Parenting

Adaptation to other fields of research is also common. Researchers have applied it to food politics (Lusk, 2018), durable goods (Gabor, 2013), palliative care (Zalensky & Raspa, 2006), and hotel employee management (Conley, 2007) to provide a sampling.

Despite its lack of empirical validation and improvements suggested by other researchers, Richter, Wright, Brinkmann, and Gendolla (2017) note that Maslow’s theory endures for its “descriptive value and plausibility” (para. 13). It continues to be widely cited in several applied social science fields. In Web of Science, his seminal 1943 article, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” has over three thousand citations with the most coming from management (450), business (299), education and education research (242), multidisciplinary psychology (220), applied psychology (189), and social psychology (167) (Clarivate, 2018). The numbers of citations appear to be growing, as his collected works received 650 citations in Scopus in 2017, up from 71 in 2003 (Elsevier, 2018).

Maslow in the Library Literature

In the library literature, Maslow’s hierarchy is generally discussed in the context of motivating employees. Ugah and Arua (2011) used it in combination with expectancy theory to urge library administration to motivate original catalogers as individuals rather than the cataloguing department as a whole. James (2011) discussed how paraprofessionals’ needs align with the hierarchy. Al-Aufi and Al-Kalbani (2014) surveyed library employees in Oman about their motivation and found that higher order needs were less likely to be satisfied than lower order needs. Crumpton (2016) joined Maslow and Grumble Theory to suggest that library leaders understand the complaints from staff in their organization as arising from unsatisfied needs. Hosoi (2005) organizes library employees’ workplace needs with the hierarchy in a helpful table that describes “well-being of others,” “accepting self,” and “meaningful work” as self-actualization (p. 44). In a reversal of approach, Walker (1994) applied the hierarchy to supervisors and administrators by encouraging hospital librarians to spend less time on “basic” library functions like cataloguing and selection so that they can devote themselves to higher profile activities like outreach that are more satisfying and motivating to hospital administrators.

However, there is some library-related work applying Maslow’s hierarchy more holistically. Francis (2010) compared information literacy to self-actualization and posited that libraries must care for students’ lower order needs lest we “become obsessed solely with providing information literacy instruction to students” (p. 142). She makes parallels between eating and sleeping in the stacks and physiological needs; library anxiety and safety needs; specialized services like popular fiction collections and belongingness needs; and staff affect and esteem needs. Pateman and Pateman (2017) marry Maslow with Karl Marx’s theories to envision a transformation for public libraries from a traditional, hierarchical and bureaucratic model to a Needs Based Library model where the library is run in a way that helps its workers and the community achieve self-actualization and positive socio-economic change.

Though not in the library field, Elissa Frankle Olinsky has done some excellent thinking about Maslow in museums. Her talk at the 2017 Information Architecture Summit, entitled “All roads lead to the bathroom,” encouraged museums to think about their visitors as whole people, which requires “solving” the lowers levels before progressing. Refreshingly, she stated, “People don’t stop having physical needs just because your content is cool” (Frankle Olinsky, 2017a, slide 16). Frankle Olinsky’s Hierarchy of Visitor Needs (2017a) has six levels:

- Accessibility and safety

- Physiological

- Basic psychological

- Higher psychological

- Highest psychological

- Self-actualization

She adds an additional tier before physiological to acknowledge the factors that may inhibit a person from visiting a museum such as ticket prices, opening hours, and services for visitors with mobility or other impairments (Frankle Olinsky, 2017a). The museum’s content addresses the three highest needs while the museum’s physical structure including entrances, signage, and washrooms address the lower three needs, called the “comfort needs.” Like libraries, museums “are in the content business” (Frankle Olinsky, 2017b, para. 5) but need to ensure that the content is not obscured by difficulties for visitors that arise when their comfort needs are not addressed.

Service Design and Project Prioritization Models

Limited resources and competing priorities are well documented in the library literature, but there is little written on how to allocate resources holistically. Although a user-centered approach is at the core of service design and other models, such as community-led librarianship (Marquez & Downey, 2015; Pateman & Williment, 2013), these methodologies are not designed for decision-making on a system-wide level.

Service design takes a holistic approach to understanding how users experience libraries’ services. Polaine, Løvlie, and Reason (2013) explain that users see “services in totality and base their judgement on how well everything works together to provide them with value” (p. 22). Once the service designer has accepted this approach, they then can focus their attention on the assessment or development of a single service within a service ecosystem. The methodology focuses on improving or developing one service at a time, not prioritizing all services relationally.

Similarly, UX strategy (Levy, 2015) integrates business strategy and UX into a framework for developing new products, while design thinking proposes a human-centered approach to understanding user needs and creating services to meet those needs (IDEO, 2015). Both approaches lend themselves to developing a culture of innovation within organizations, but neither are designed to provide a decision-making matrix in complex, multi-touch point environments, such as libraries.

Digital collections is one area of librarianship that has a well-developed body of literature on project selection and prioritization. Hazen, Horrell, and Merrill-Oldham (1998) discuss the complex nature of selecting collections to digitize, which includes considerations of intellectual value, potential audience, cost of digitization, relationship to other digitization projects, and copyright concerns. Their overall conclusion is that these decisions will factor in practical, measurable concerns but will ultimately be driven by the organization's values and goals. Ooghe and Moreels’ (2009) scan of the literature and frameworks for selecting digitization projects found a gap in transparency and consistency in decision-making and proposed a set of twenty-five criteria which could be used to improve the selection process and cross-institutional communication. Balancing user and institutional needs is a frequent concern in the digital collection literature (Boock & Chau, 2007; Bantin & Agne, 2010; Mills, 2015). Vinopal and McCormick (2013) propose a tiered model for understanding the resource requirements of digital scholarship projects, which allows libraries to make informed decisions on what to prioritize.

Hierarchy of Library User Needs

We propose a model for library resources and services that is similar in spirit to Maslow’s hierarchy, but not a direct translation (see fig. 3). Like the original, the Hierarchy of Library User Needs proposes five categories organized hierarchically:

- Library as Minimum Viable Product

- Library as Convenience

- Library as Connector

- Library as Incubator

- Community as Library

1. Library as Minimum Viable Product

In Maslow’s model, the first category contains the basic physiological functions and appetites that the body needs to stay alive (1943). Within the library context, this tier comprises the building blocks of what makes a library a library. These elements act as the structure of the library upon which the other services and offerings can be built. For example, a reading room must be inside a library building, just as circulation services would be useless without a cataloged collection. If a library were a person, these items would be the elements that it needs to exist. In most traditional libraries, the collection and physical spaces are examples of minimum viable product.

2. Library as Convenience

Once the minimum requirements of a library are in place, we layer elements that user communities most commonly need. Computer workstations and circulation services are examples of common conveniences. These are the things which make the library a convenient institution to rely on. They are simple needs that users expect to work seamlessly. They are only conveniences if they are actually convenient. These items are in the second category of basic needs because they cannot be implemented without the items in the first category in place.

Here we depart from a direct translation of Maslow’s second tier, the safety needs. None of the library elements in our model contribute to a user’s physical safety exactly, though they do contribute to their comfort and ability to accomplish day-to-day tasks.

3. Library as Connector

Once the user’s everyday needs are satisfied, we can begin to assist with higher order needs. Maslow’s third category, which he calls “the love needs” (1943), are where good relationships start to make a direct impact on a person’s happiness. In this category, a person will “hunger for affectionate relations with people in general, namely, for a place in his group, and he will strive with great intensity to achieve this goal” (p. 381). The library can assist with this goal in three ways: (1) by building relationships directly between the user and library staff, (2) by helping the user meet and bond with their peers, and (3) by helping them to feel like they belong in their peer group.

Previous work applying Maslow’s theory of motivation to library services also ascribes good relationships with library staff at this level (Anderson, 2004). We certainly concur as more of the services we propose in this tier require library staff than any previous tier. Examples might include information services, reference, and teaching. All interactions with staff should communicate that the user is welcome and belongs at the library. For example, outreach and liaison programs are important for building and maintaining warm relationships between the user and the library, but these must be backed up by courtesy and warmth from the library’s public service staff or the liaison/outreach efforts will be undermined.

Libraries’ status as a “third place” in the community means that it is a popular place for community members to gather. This happens in both structured and unstructured ways. In a public library, parents with young children love storytime programs while teens appreciate the safe and free space to be with their friends away from the direct supervision of their parents and teachers.

We also see a broader application of the “love needs” to libraries. Library services and resources can help a user develop skills for success in their academic, professional, or personal lives, depending on the library’s mission and community. These skills can help a person to feel secure in their place in the community. For example, a workshop or reference interaction can help a student complete an assignment successfully thereby maintaining good (academic) standing amongst their peers.

4. Library as Incubator

Maslow’s fourth level has to do with feelings of prestige and self-esteem which he defines as “that which is soundly based upon real capacity, achievement, and respect from others” (1943, p. 382). In this, the parallel to library services is quite direct. These are the things we can do to help users achieve prestige and success in their chosen fields. Here we imagine services and resources meant to address more advanced user needs, like audio-visual content creation or mapping software.

These services and resources require mastery from both the user and library staff. They require significant time and energy and are therefore likely to be accessed only by motivated or more sophisticated users. It follows that these services will be accessed less frequently than those discussed in the previous tiers. The specialized services in this tier often require significant funding to create and maintain. For example, a small, underfunded public library system may struggle more than a large, urban system to be able to afford a fully appointed makerspace.

5. Community as Library

Maslow’s highest tier describes the drive to reach self-actualization, which he explains “as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming” (1943, p. 382). This level has been criticized as being ill-defined (Daniels, 1982), but we will take him to mean realizing one’s highest potential. Within a library context, this will depend on the community served, but fundamentally it will involve community-led practices and projects. In this tier, the library seeks to remove the divide between service provider and user. This category also includes areas in which libraries can use their expertise to advocate for the central ideals and values of our profession.

It is at this tier that the barrier between library and community becomes permeable. Initiatives such as community-sourced metadata, services co-created with community partners, and collaborative design projects all require libraries to invite people not employed by the library to contribute in significant ways. The libraries provide the structure, space, or resources and invite the community to build it up. In this tier, libraries may also move outside the realm of service provider to become advocates for causes that are central to our values. The results of these efforts may be intangible, hard to measure, require a longer period for results to become clear, or fail entirely.

Community as Library will look different depending on the type of library and its mission. We imagine that the actions in this tier will be guided by the community’s needs. Libraries may not spend significant resources in this area, but they will frequently be high-profile projects that may involve collaborations that leverage the resources of multiple libraries or library organizations.

Applying the Model in Theory

To illustrate this conceptual model, we present three examples of how it might look if applied. We have provided a brief sampling of what might fit into each tier for three very different fictional libraries and their communities. The example libraries below are meant to demonstrate how variable service prioritization can look, not to provide an authoritative representation.

Both Maslow’s hierarchy and the Hierarchy of Library User Needs have fixed tiers. Maslow’s hierarchy has also defined what falls into each tier, whereas the Hierarchy of Library User Needs is a bit looser, allowing the arrangement of services within each category to vary depending on the library’s unique mission and community. The goal is to provide a frame for libraries to use to organize their understanding of their user communities. Any library wanting to apply this model will have to validate it with data and input from users at their own institutions and consider local mission, needs, services, and contexts.

Example 1: Academic Library

This academic library serves a mid-sized, centralized, publicly funded, doctoral granting, urban university. This is the only library on campus. The student population is mostly commuter.

Library as Minimum Viable Product

Sample Services:

- A cataloged collection with access points such as a catalogue

- Wireless internet and computer workstations

- Safe and accessible physical space

Rationale:

For an academic library, the collection and access to it is the main reason for being. Access to the internet is important as a large portion of the collection is online. The commuting nature of this user community means that the library is an important on-campus hub; it must be a pleasant and useful place to be.

Implications:

The bulk of this library’s budget is directed to its collections, both physical and digital. A significant portion of library staff time is dedicated to ensuring that the collection’s access points, including the catalog and link resolver are working properly. User research and projects that improve these services are ongoing.

Library as Convenience

Sample Services:

- Independent study spaces so users can view the collection or work

- Printers and scanners

- Technology and technology accessory loans such as laptops, dongles, or phone chargers

Rationale:

Since this library serves a commuter campus, having space to spend time between classes is a big concern to students. Printers and scanners are not readily available in other campus locations, so they are convenient. Likewise, loanable technology allows students to spend the whole day on campus without having to worry that their phone or laptop will die.

Implications:

The services in this tier are largely self- service and do not require much ongoing financial or staff commitment beyond maintenance. This library has dedicated a fund to replace or refurbish equipment as needed. In the longer term, they are working with university advancement to fundraise for a renovation to improve study spaces.

Library as Connector

Sample Services:

- Space to gather including group study spaces

- Education and support services like workshops and reference

Rationale:

The library helps students connect with one another which is especially important for commuters who may feel isolated living far from campus. Workshops and research services help students achieve their academic goals.

Implications:

Most librarians at this library dedicate a portion of their time each week to working with users both one-on-one and in workshop settings. Periodically, the library reviews how the space is used to ensure that they are achieving the right balance of quiet and group study spaces.

Library as Incubator

Sample Services:

- Special equipment and software such as 3D printers, data visualization spaces, and licensed software for GIS, data manipulation, and design

- In-depth research support for labor-intensive methodologies such as systematic reviews, text mining, or web archiving projects

Rationale:

The library supports its advanced researchers by providing in-depth expertise and costly software, which would most likely be out of reach for the individual user if not provided by the library.

Implications:

The decision to provide these advanced services and equipment were carefully tailored to the needs of the user community as informed by extensive user research and implemented strategically to ensure that they would be worth the financial and time investment. Services at this level are reviewed periodically to ensure that they continue to be relevant to users. Those that are found to no longer be relevant are discontinued.

Community as Library

Sample Services:

- Partnerships with other student support offices on campus to create mental health support programming

Rationale:

Partnering with other campus offices to increase student wellbeing is a way the library can participate in community building outside the confines of traditional library services.

Implications:

Administrators at this library are active in both the university and the broader community. After discussion with potential partners, they looked for projects that would maximize the skillsets of both groups while addressing the shared values of both partner-organizations.

Example 2: Public Library

This library system is comprised of three small branches in a rural area that has few job opportunities. There is a large population of retirees, and the system is underfunded by its municipality. Internet quality and coverage in the region is low.

Library as Minimum Viable Product

Sample Services:

- A cataloged print collection strong in both leisure reading and practical non-fiction topics

- Safe and accessible physical space

- Computer workstations and strong wireless internet throughout each branch

Rationale:

With poor internet in the area, users can usually only access this library’s services and collections in person. The library is often the only way that many members of the community can access the internet, so providing it is a basic need.

Implications:

Like most libraries, the collection takes up a significant portion of the library’s budget. This library has prioritized the best available internet, both wireless and wired, to ensure that users can depend on the library for internet access.

Library as Convenience

Sample Services:

- Circulation services

- Circulating home internet hot spots

Rationale:

Circulating physical library resources is a major convenience as it allows the community to use the collection outside of a library branch, which may be far from their homes. Likewise, it is more convenient for users to be able to take the library’s internet home with them.

Implications:

Last year this library implemented self-checkout machines, freeing staff time for higher level tasks. The home internet hot spot pilot was grant funded and addresses long standing demand within the community.

Library as Connector

Sample Services:

- A bookable meeting room for groups in the community to gather

- Open educational and social programming for adults such as book or gardening clubs

Rationale:

Social isolation is common among seniors and is statistically associated with poorer health outcomes (Tomaka, Thompson, & Palacios, 2006). This library provides space for already-connected seniors to gather and opportunities for isolated seniors to make new social connections.

Implications:

Librarians at this library spend a portion of their time working on programming because user research and feedback has consistently showed that it is both popular and valued by the community. This is also why a dedicated meeting space in each of the three branches has been maintained despite the relatively small size of two of the branches.

Library as Incubator

Sample Services:

- Workshops focusing on resume writing, entrepreneurship, and common technologies like Excel

Rationale:

The library helps its users achieve reliable employment by bringing in experts to teach practical job skills.

Implications:

The library has partnered with local businesses and governmental bodies to find experts to teach these classes. Though there is sometimes a fee associated, the library maintains a small fund in the budget and often negotiates non-profit discounts.

Community as Library

Sample Services:

- Co-designing a new branch

Rationale:

This library recently received funding for a new branch. Instead of merely consulting with community groups, the library is embedding community members in the design process and making an effort to reach out to underrepresented groups to ensure that no one’s needs are overlooked.

Implications:

The funding for the new branch was the result of years of advocacy and awareness raising with local government and constituents. Embedding users in the design process was a promise of the campaign and, though it has not yet been attempted in the region before, local government is keen to see (and approve) the results. If successful in engaging a broad cross-section of community, it is more likely that their varied community will be able to see themselves reflected and included in the new space possibly increasing usage.

Example 3: Online-Only Medical Library

This library is embedded in a teaching hospital, but not responsible for patient service or education. Researchers and clinicians work on multiple physical sites in several clinical disciplines and access library resources and services online. There is no physical library location, only office space for library staff.

Library as Minimum Viable Product

Sample Services:

- A cataloged collection of online medical journals and digital resources like UpToDate

- A usable website including a catalog of the collection and medical databases

Rationale:

Since this library serves practitioners across several locations, a collection strong in the medical disciplines of the institution and an easy way to access them remotely is the minimum viable product.

Implications:

Since physical space is less of a concern for this library, a higher proportion of the budget is dedicated to online resources, which can be quite expensive. This library also has high proportion of technical staff members to ensure that access to the e-resources is seamless.

Library as Convenience

Sample Services:

- Interlibrary loan

Rationale:

This library has limited funds and some important publications, like Nature, are simply too expensive. An interlibrary loan service gives users a convenient way to access publications the library does not subscribe to.

Implications:

This library participates in a consortium of university and medical libraries. The costs are absorbed by the library, not passed to the user.

Library as Connector

Sample Services:

- Email and chat reference

Rationale:

When this library’s users need to connect with library staff to resolve issues, they need to be able to do so quickly and remotely.

Implications:

There are few librarians in this library, so they dedicate a large portion of their time to assisting users remotely.

Library as Incubator

Sample Services:

- Impact metrics services

Rationale:

To support pre-tenure and research-active users, this library offers an impact metrics service so users can present the most accurate picture of their work and its reception in the field.

Implications:

This service was developed after user research indicated that the community was struggling with this task. Only one librarian has been assigned to this service, but requests have so far been manageable and the librarian has been successful in training the faculty’s research assistants in the procedures.

Community as Library

Sample Services

- Systematic review co-authoring

Rationale:

Many medical librarians participate as co-researchers in systematic reviews and other forms of knowledge synthesis. This uses their research skills in creating new knowledge and improves the quality of the final review.

Implications:

Though this service does not require any additional financial investment, it is time consuming. Consequently, the librarians on staff accept invitations to join research teams, but are carefully documenting the impact of their efforts in hopes of being able to hire a dedicated librarian since this activity has such potential to improve the knowledge produced at the institution.

What Goes Where?

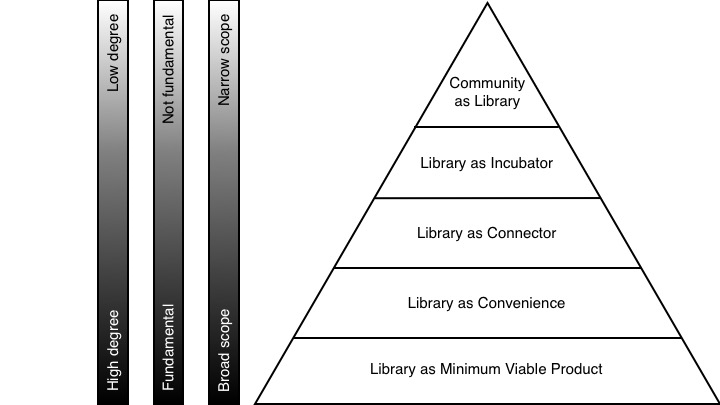

As Maslow was talking about an individual, relating his theory of motivation to an organization that serves individuals requires careful thought. To help us organize library services into the five tiers, we consider three concepts (see fig. 4):

Degree

Key question: How important is an element to those who use it?

The absence of lower tier items will have a stronger negative effect on users than the absence of those in the higher tiers. For example, an accessible entrance is essential to using the physical library for those who require mobility accommodations. This feature may only be needed by a small percentage of the user community, but those who need it would be greatly affected if it were not there.

We think of this concept in terms of value proposition design (Osterwalder, Pigneur, Bernarda, Smith, & Papadakos, 2014). The services in the lower categories tend to be “pain relievers” that remove obstacles to achieving users’ goals while the upper categories are more likely “gain creators” that add unexpected value to users’ lives. Circulation relieves the pain of having to access the collection in person at the library, whereas an experienced reference librarian can help create gains for researchers embarking on a difficult project.

More than the other concepts, determining the degree of an element requires user research. In order to fully understand which services are important to users and the role that service plays in their lives, library staff must get the users’ perspectives or risk making erroneous assumptions. Degree should not be determined by library staff alone.

Fundamentality

Key question: Which elements depend on which?

The more fundamental an element is, the more other elements depend on it to function. For example, a reference desk is impossible without a library building and a research guide is impossible without a website. An element with few or no other elements depending on it is less fundamental than one with many depending on it.

Service design tools are well suited to help determine fundamentality as they help make explicit “how different touchpoints work together to form a complete experience” (Polaine et al., 2013, p. 45). By understanding the interconnectivity of services from a user perspective, libraries will be better able to determine fundamentality.

Scope

Key question: What proportion of the user population accesses each element frequently?

Some elements may affect everyone while others affect very few. Elements that are higher up in the hierarchy will be directly beneficial to fewer users. For example, more users will benefit from the library’s free Wi-Fi than its music librarian’s expertise. Items in the fifth category, Community as Library, have a narrow scope because fewer users are involved or benefit directly even though the indirect benefits may be strong indeed. Advocacy work with government, for example, has a narrow scope because few users are involved, but the effects of successful efforts could have a very broad indirect scope.

In general, the more fundamental, the higher degree, and the broader scope, the lower the service or resource should appear in the Hierarchy of Library User Needs. As we ascend, the services and resources become less fundamental with a weaker degree of impact, and a narrower scope.

There are library resources and services that may be high in one area, but low in the others. Gender-neutral washrooms, baby changing stations, and accessibility accommodations are examples of services with high degree but low scope and fundamentality. Following the Seven Principles of Universal Design (National Disability Authority, 2012), we weigh degree more heavily as “Provisions for privacy, security, and safety should be equally available to all users” (1.c.). Additionally, although these services may be developed to ensure accessibility and usability for specific user groups, universal design benefits all users.

When applying this model, consider that a library unit’s activities may fit in multiple tiers, depending on the context. For example, a map library within the context of a library system could fall into the fourth tier, Library as Incubator. Within that library, however, the space and collection would be considered the first tier, Library as Minimum Viable Product. When placing services within the model, context is important. This could help units prioritize their activities for smaller-scale planning within a broader strategic context. It might be useful for units to know where the bulk of their activities fall within the broader organization’s tiers, just as it could be for administrators to be reminded of each unit’s contributions to each tier. It works as both a macrocosm and a microcosm, in this way.

Discussion

Using the Model for Decision-Making

We offer this model as a possible strategic planning tool for libraries. We especially hope that it may be used to assess (or reassess) staff and budgetary allocations. The most time and money should go to the bottom tier of the model and decrease as the tiers rise. We have not included benchmarks for each tier—though a library could certainly aim to devote 5 percent to Community as Library activities, 10 percent to Library as Incubator initiatives, and so on. Instead, we hope it will stimulate conversations within a library, especially at administrative levels. Any tier could be over- or under-invested in; the model is there to help libraries identify and correct imbalances.

One common position we have seen is an overinvestment or overemphasis in the fourth tier, which we call Library as Incubator and entails specialized facilities, services, and staff to serve a minority of advanced users. These services are very exciting and allow the library to address emerging needs that may become more standard in the future. 3D printing, for example, was once a fringe interest but is now becoming commonplace in many occupations and even taught in elementary schools (Trust & Maloy, 2017). Many special, academic, and public libraries are rushing to implement 3D printing services and facilities for their communities. These facilities certainly benefit the patrons who use them, but we fear that they are sometimes adopted at the expense of more quotidian community needs. We hope that under the model we propose, libraries evaluate whether the efforts they pour into such a service are in proportion with the other tiers. Have the low tiers been satisfactorily addressed? User experience work should be able to answer this question if it is not already apparent from the number of complaints (or lack thereof) from your users. If the answer is no, it may be best to scale back your 3D-printing plans until the basic needs are addressed. Put another way: don’t buy a 3D printer until your regular, paper printers are reliable and easy to use.

We understand that several factors may tempt a library’s administration to put higher-tier activities above those in the lower-tiers. They are more exciting to donors and funding bodies than operations, so it may be possible to obtain funding for these projects over other, less “sexy” (though perhaps more necessary) budget lines. Participating in these advanced or emerging areas of needs also signals that the library system is keeping pace with rapid technological change. These are not trivial concerns. However, these services do not make the strongest impact on the most users. In addition to providing the high-level services, a user-focused library will also value improvement of the more basic elements, as they are aware that they have broader impact. Advanced services should not be implemented in such a way that diverts funding or staff attention from the urgency and primacy of the services and resources discussed in the previous tiers.

Another common situation is an underinvestment in the top tier (“Community as Library”). This tier is easy to forget about because it might not be explicitly included in a library’s mandate—though we encourage libraries to do so. It is also the tier that contains activities that may not benefit users directly or immediately. It can be hard to justify activities that produce intangible results, such as advocacy. Libraries are interested in quantifying their activities in order to demonstrate value. Taking on partnerships or advocacy work often yields increased awareness or improved relationships, which cannot be easily visualized in an annual report. Some libraries have managed to quantify their contributions, however. After the Edmonton Public Library hired outreach workers to engage members of the community at the library’s downtown branch, they produced a social return on investment report estimating that their program saved the city 3.56 million CAD (Berry, 2014). Short term, quantifiable measures such as savings or return on investment are persuasive to a funding body, but longer-term, subtler impact may provide value that is hard to measure. How could a library quantify the extent to which they are acting on their most deeply held values?

Maslow (1943) acknowledged that a person’s basic needs were in a constant state of partial fulfillment. Otherwise, we would not be able to go on a date or to a class lecture if we were at all hungry or cold. As long as we are usually adequately well fed and warm, we can still focus on higher order needs such as love or self-actualization. Similarly, we do not expect a library to be perfect on every level before tackling items on the higher levels, but the lower levels should be more functional and well-resourced than the ones above it.

This model is meant to highlight the unique value each of the library’s services and activities provide to users irrespective of their perceived prestige. Lower tier elements are in no way lesser because they fall lower on the hierarchy. Rather, they are crucial to the operation of the whole organization, and usually touch a far greater number of users. Making improvements to these areas will have a broad impact. Those that fall in the higher tiers are likewise not rarefied extravagances that must be abandoned. On the contrary, these are services that few others are positioned to offer. Libraries can capitalize on their unique role to support users in ways that few other organizations can. We should shine a light on these services to draw attention to our value.

Where Do Users Fit In?

UX research is essential to interpreting this model in a specific library’s context. Taking a user-centered approach to evaluating resource allocation will allow libraries to honestly assess how they are meeting user needs. We anticipate that many libraries already have access to studies like LibQual+, Ithaka S+R Faculty Survey, or Measuring Information Service Outcomes that can help them triangulate where a service or resource should fit in the pyramid. Additionally, institutions could use some of our criterion, especially degree and scope, to place items into tiers by asking users if they use a service and how important it is to them. The authors conducted a pilot study to do just this (Logan & Everall, 2019). The point of this tool is to help libraries allocate resources in proportion to user needs and expectations, but these needs and expectations should be researched and validated using both qualitative and quantitative methods, since we are not our users. Libraries should review and update their understanding of user needs often to ensure that we keep pace with changes. If we are making decisions based on library assumptions about what our users need, or worse yet, based on what we think is best for them, we risk obsolescence.

It is important to be inclusive and broad in identifying users when applying the Hierarchy of Library User Needs. Libraries can easily miss marginalized or non-traditional user populations. Frankle Olinsky’s model includes a sixth tier placed below physiological needs for accessibility and safety to acknowledge that people are free to visit or choose not to visit a museum (2017a). She insists, “We throw out the entire rest of the pyramid if the visitor never enters the building” (slide 20). Libraries are in a somewhat similar situation. We tend to have assigned communities. Public libraries serve municipalities or regions; academic libraries serve their institutions of higher learning; legal libraries serve their law firms. However, we are well aware that our users now have a great deal of choice about how to access resources in our digital age. We cannot complacently assume that our user community is a captive audience. User research, liaison, and Library as Connector activities can help us to connect with, understand, and build relationships with aspects of our community that we may not be as familiar with.

Not all members of the community will access all levels equally. Community members with economic or experience advantages may not access services in the lower tiers, but they may come to the library for those in the higher tiers, the “gain creators” that have lower degree. For example, those that have good internet service at home may not care very much about the library’s free Wi-Fi just as an advanced researcher may not need to come to the library for information literacy instruction. These users have already satisfied the needs that the lower tiers are aimed at addressing elsewhere and do not need the library’s help. Conversely, users whose lower-tier needs have not yet been met may be less likely to access services and resources in the higher tiers. First year undergraduates are more likely to need a quiet place to study than a librarian’s text mining expertise just as a person struggling with underemployment is more likely to attend a job interview preparation workshop than have the time to sit on the library’s board. It is up to the library to understand their user community and address their variety of needs in the most appropriate way; the Hierarchy of Library User Needs is one lens that libraries can use to do this.

Conclusion

We believe Maslow’s hierarchy has the potential to be a helpful mental model for contextualizing and prioritizing library user needs. Since UX and service design experts are few in libraries, they frequently choose to focus their attention on projects with broad reach that can have a positive impact on the most users. Although this is the modus operandi within the UX field, it can be challenging to communicate these values to decision makers. The Hierarchy of Library User Needs might provide a framework that can be used to start those conversations. Libraries can draw upon the vast amount of data and research they generate to start populating the categories. This exercise could not only help staff think honestly about user needs, but also potentially provide a chance to speak openly about the organization’s priorities. This is messy work. The goal of it, though, is to ensure that libraries keep our users’ needs at the very core of our organizations. It can be part of a process of continual discovery and realignment, of questioning and listening without agenda, and of acting in good faith on our discoveries: empathy in action.

References

- Al-Aufi, A., & Al-Kalbani, K. A. (2014). Assessing work motivation for academic librarians in Oman. Library Management, 35(3), 199–212.

- https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-03-2013-0020Anderson, S. B. (2004). How to dazzle Maslow: Preparing your library, staff, and teens to reach self-actualization. Public Library Quarterly, 23(3–4), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1300/j118v23n03_09

- Bantin, J., & Agne, L. (2010). Digitizing for value: A user-based strategy for university archives. Journal of Archival Organization, 8(3–4), 244–250.https://doi.org/10.1080/15332748.2010.550791

- Berry, J. N. (2014). 2014 Gale/LJ Library of the Year: Edmonton Public Library, Transformed by teamwork. Library Journal, 139(11), 30.

- Boock, M. H., & Chau, M. (2007). The use of value engineering in the evaluation and selection of digitization projects. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 2(3), 76.https://doi.org/10.18438/B8HG6H

- Clarivate. (2018). Web of science [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.webofknowledge.com

- Conley, C. (2007). Peak: How great companies get their mojo from Maslow. John Wiley & Sons.

- Crumpton, M. A. (2016). Understanding the grumbles. Bottom Line: Managing Library Finances, 29(1), 51–55.https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-10-2015-0019Daniels, M. (1982). The development of the concept of self-actualization in the writings of Abraham Maslow. Current Psychological Reviews, 2(1), 61–75.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02684455

- Downer, A. (2017). Hierarchy of needs pyramid parodies. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/hierarchy-of-needs-pyramid-parodies

- Elsevier. (2018). Scopus [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/

- Francis, M. (2010). Fulfillment of a higher order: Placing information literacy within Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. College & Research Libraries News, 71(3), 140–159.https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.71.3.8336Frankle Olinsky, E. (2017a). All roads lead to the bathroom. Presented at the IA Summit 2017. Retrieved fromhttps://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1aAjm54ZennXeFwJOlS0umzgC5JVHYDFWrOvsM4RT0Ps

- Frankle Olinsky, E. (2017b). Maslow in museums [Blog]. Retrieved March 5, 2018, from https://www.museums365.com/maslow-in-museums

- Gabor, M. R. (2013). Endowment with durable goods as welfare indicator. Empirical study regarding post-communist behavior of Romanian consumers. Engineering Economics, 24(3), 244–253.

- Hazen, D., Horrell, J., & Merrill-Oldham, J. (1998). Selecting research collections for digitization. Council on Library and Information Resources. Retrieved fromhttps://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/hazen/pub74/

- Hosoi, M. (2005). Motivating employees in academic libraries in tough times. In Association of College Research Libraries Twelfth National Conference. Minneapolis, MN.

- IDEO. (2015). Design thinking for libraries: A toolkit for patron-centered design. Palo Alto: IDEO. Retrieved fromhttp://designthinkingforlibraries.com/

- James, I. J. (2011). Effective motivation of paraprofessional staff in academic libraries in Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice, 38–46.

- Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 292–314.https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369469Levy, J. (2015). UX strategy: How to devise innovative digital products that people want. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

- Logan, J., & Everall, K. (2019, June). How would users prioritize library services in a Hierarchy of Library Needs? Poster session presented at the Evidence Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP) 10, Glasgow, Scotland. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1807/96449

- Lusk, J. (2018, August 21). Hierarchy, disagreement, and food politics. Retrieved September 4, 2018, fromhttp://jaysonlusk.com/blog/2018/8/15/disagreement-and-food-demandMarquez, J., & Downey, A. (2015). Service design: An introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(2).https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.201

- Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality (1st ed.). New York: Harper.

- Mills, A. (2015). User impact on selection, digitization, and the development of digital special collections. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 21(2), 160–169.https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1042117

- National Disability Authority. (2012). The 7 principles. Retrieved August 28, 2018, fromhttp://universaldesign.ie/What-is-Universal-Design/The-7-Principles/

- Ooghe, B., & Moreels, D. (2009). Analyzing selection for digitization: Current practices and common incentives. D-Lib Magazine, 15(9/10).https://doi.org/10.1045/september2009-ooghe

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., Smith, A., & Papadakos, T. (2014). Value proposition design: How to create products and services customers want. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Pateman, J., & Pateman, J. (2017). Managing cultural change in public libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 36(3), 213–227.https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2017.1318641Pateman, J., & Williment, K. (2013). Developing community-led public libraries: evidence from the UK and Canada. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Polaine, A., Løvlie, L., & Reason, B. (2013). Service design: From insight to implementation. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Rosenfeld Media.

- Richter, M., Wright, R. A., Brinkmann, K., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2017). Motivation - Psychology. In Oxford Bibliographies Online.

- Soper, B., Milford, G. E., & Rosenthal, G. T. (1995). Belief when evidence does not support theory. Psychology & Marketing, 12(5), 415–422.https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120505Tomaka, J., Thompson, S., & Palacios, R. (2006). The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health, 18(3), 359–384.https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305280993

- Trust, T., & Maloy, R. W. (2017). Why 3D Print? The 21st-century skills students develop while engaging in 3D printing projects. Computers in the Schools, 34(4), 253–266.https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2017.1384684Ugah, A., & Arua, U. (2011). Expectancy theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and cataloguing departments. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal). Retrieved fromhttps://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/637Vinopal, J., & McCormick, M. (2013). Supporting digital scholarship in research libraries: Scalability and sustainability. Journal of Library Administration, 53(1), 27–42.https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.756689

- Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(2), 212–240.https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6

- Walker, M. E. (1994). Maslow’s hierarchy and the sad case of the hospital librarian. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 82(3), 320–322.

- Zalenski, R. J., & Raspa, R. (2006). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: A framework for achieving human potential in hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(5), 1120–1127.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1120