Participatory Approaches to Building and Improving Learning Ecosystems: The Case Study of the Library for Food Sovereignty

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This paper explores participatory processes for bringing diverse user groups into the design and development of learning ecosystems. It draws on the case study of the Library for Food Sovereignty, a project working to create a local knowledge commons for smallholder farmers in East Africa. Using participatory technology development methodologies as a framework to build upon, I discuss opportunities for integrating the critical perspectives of user groups into the design process. This development methodology is primarily used in agricultural extension, but its principles are increasingly valued across fields. Central to the approach is the belief that we can improve the health of the whole system by working with the uniqueness of places and the people that inhabit them. Crucially this includes valuing and leveraging the perspectives and unique attributes of communities. Libraries that are starting to explore processes and approaches to improving the information ecosystem—especially libraries with diverse patron groups—can learn a lot from the Library for Food Sovereignty case study. The processes explored in this paper can help create library information ecosystems that are not only meeting the unique needs of diverse patrons but are also transforming the learning process.

This paper was refereed by Weave's peer reviewers.

Opening Synthesis

Typically, an author might open up the case study analysis by describing the aim of the project and what the intended objectives and outcomes were. However, part of what makes participatory technology development work as an approach to development and learning is the principle of co-discovering the needs of the community and conceptualizing the services to meet those needs. So, I start this case study with a mystery: how can we support and accelerate the peer-to-peer learning process of smallholder farmers in East Africa so that they can create a healthier and more just food system? What does this look like? What qualities does it have? Who manages it? At the start of this project I didn’t know, and so you, dear reader, won’t know right away either! As I discuss our case study, it will reveal important insights that helped shape our final product; a product that is being co-created with the community to help stimulate a larger transformation beyond the service itself. This mirrors a key part of participatory technology development and the case study as an approach: the process exists to help determine what it is you need to build and to improve the learning ecosystem as a whole.

Participatory Technology Development & Service Design

Participatory Technology Development

Participatory technology development is an approach to learning and innovation used in sustainable agricultural development that became popular in the 1970s. At its core, it is a process by which researchers and farmers work together to test and analyze alternative farming practices and technologies. One of the main goals of this interactive approach is to understand the dynamics of farming systems and to identify priority opportunities and ways to align macro-level efforts with the local needs of farmers. It is as much about developing the capacities of farmers as it is about finding solutions. For example, practitioners prioritize fostering self-confidence and innovation in farmers by letting the farmer initiate and then lead research efforts. This allows the farmer or farming community to assess current practices, local conditions, and community way of life and then identify the best steps for improvement. Oftentimes men and women have variant lifestyles and roles in traditional farming communities, and these variations create distinct barriers to development and access to resources. In the Global South, for example, there is a major gender gap between the resources available to male farmers and those available to female farmers. Women, who make up to 70 percent of the agricultural workforce in developing countries and produce 60 to 80 percent of the food, have significantly less access to a range of resources including land, credit, education, and technology (Hawken, 2017, p. 76). The participatory process therefore allows some of those considerations to surface before moving forward with a development plan (Veldhuizem, Water-Bayer, & de Zeeuw, 1997, pp. 4-6).

Service Design

A useful portal into understanding and being able to transfer the participatory technology development approach in a library context is service design, a user-centered design approach to creating or improving a service. Service design also centers around processes, innovation, and understanding the dynamics of a system. It is helpful to examine how these two processes are synergistic, but also to be aware of their differences.

Marquez and Downey (2015) have applied service design to libraries, where the library is considered as a whole, viewing all its various systems as a service ecology. In “Designing for Services,” authors Birgit Mager and Tung-Jung (David) Sung write, “Co-creation is one of the driving forces [in service design], involving users, rather than employees and other actors in order to integrate the expertise of those that are in the heart of the service experience and mobilizing energies for change” (Mager & Sung, 2011, p. 1). This approach rings true to the participatory technology development process, which prioritizes the perspectives and contexts of farmers, including experiences and attitudes that exist before development begins and those that persist long after it is complete. The two approaches are not isolated, one-time methods; they are integrated and holistic practices meant to build on what is already happening in a given context. These methods can also be used to bring out the critical perspectives of library patrons; for example, the experiences and unique information needs of users across diverse economic, cultural, social, religious, or ethnic groups.

Differences

By emphasizing some of the key differences between service design and participatory technology development, I will attempt to illuminate how libraries can improve not only services but also learning ecosystems as a whole. Service design, although geared towards users, is fundamentally attempting to improve a particular service and make it more efficient (Heath, 2014). Participatory technology development, on the other hand, is working to cultivate mutually-beneficial relationships that spur learning transformation. So, we can say that service design is about service improvement and the participatory approach is developmental. This is especially relevant as many services typically provided by libraries are increasingly available online; what potentially makes a library irreplaceable therefore is a combination of services, but also a positive and inclusive learning ecosystem. Libraries can integrate the process-oriented aspects of participatory technology development with service design to increase the developmental potential of the library environment.

Co-Creation and Local Perspectives

Agriculture, like information needs and services, is site-specific. What is a valid farming method or technology in one place can be irrelevant or ill-advised in another. Having the community identify their priority needs and opportunities is a great way to begin finding solutions to improving agricultural practices that are right for a particular context or group. Since participatory learning is based around exchanges, this process begins with the farmer. One such example is the story of the farmer-led adaptation of a local water-management innovation in Ethiopia. Abadi Redehay, a family farmer who grows mainly teff and chickpeas in the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia, developed an intricate underground system of draining and harvesting water from waterlogged land. Since each plot of land in the region is different, the innovation cannot be copied exactly nor can other farmers compare treatment and control of the technique. The underlying principles of the water-management method can, however, be shared and applied under different soil and land conditions if interested farmers dig canals that work with the specifics of their slopes (Araya, Tebari, HaileSelassie, & Redehay, 2010, p. 44). Where this local solution thrived, a one-size-fits-all or top-down method would likely have failed. In this case, local development NGOs and researchers played merely a facilitator by supporting Abadi Redehay to travel around and teach neighboring farmers the underlying principles of his technique. Librarians who have a unique user community can take a lot from this simple anecdote. By applying the underlying principles of participatory and bottom-up service assessment, librarians can better tailor resources and services to the specific and often unique needs of their patrons.

The story of the joint experiment to improve local fish-smoking ovens called banda in Niger is a good example of how NGO presence can support innovation processes by first identifying the unique needs and traditions of the community. In this case, a community in the Sahel developed the banda ovens as an improvement from the three-stone open-fire stove still used in many other villages. In the Sahel, fish smoking is typically done by the women, whereas gathering fish is a task the men do together. Both men and women sell the fish at markets and fish is commonly given as a gift to relatives (Magagi, Diop, Toudou, Seini, & Mamane, 2010, p. 35). After some time using the banda, the community identified some limitations, including limited smoking capacity, the need for constant supervision to keep away stray dogs, the inability to use the banda on rainy days, and the poor quality of smoked fish. Due to added costs they were unable to make improvements. This changed when a team of scientists and researchers from the Prolinnova Niger decided to set up a co-funding and joint experimentation project with the community. Together the scientists and community were able to analyze and make adjustments that improved the technology of the stove and also supported the traditional roles of men and women in gathering the fish, cooking it, gift giving it to friends and relatives, and selling it at local markets (Magagi et al., 2010, p. 35). This is a great example of how letting communities take the lead sets the groundwork for developing sustainable and relevant technologies that improve the lives of not just some groups but all. In contrast, when top-down methods or transfer technologies are passed down by agricultural extensionists (usually to men) they rarely meet the dynamic—and sometimes very specific—needs of communities and don’t last long. Libraries that rely mainly on top-down instruction could consider peer-led instruction as a way to draw out some nuanced needs of patrons; furthermore, participatory approaches could even help design such programs together with students.

The importance of co-creation is pivotal, meaning that relationships and other social dynamics cannot be ignored. This is an underlying idea in service design, for example, but it needs to be drawn out further. In Service design: from insight to implementation, the authors emphasize that understanding people and relationships, often via co-designing, can be the difference between a service that fails and one that thrives. Furthermore, context and the unique ways that users interact with services are critical and best incorporated directly in the situations where people use the service—not in a lab (Polaine, Løvlie, & Reason, 2013). This can be expanded by learning from participatory technology development and how the process moves beyond the design of a service to a developmental learning process that has the potential to transform the learning ecosystem altogether.

A complementary example to these participatory anecdotes is a research project conducted by librarians at the University of Rochester, a library known for its innovative and forward-thinking approaches to outreach and service assessment. One of the main goals of this project was to better understand how undergraduate students write research papers using anthropological and ethnographic methods to examine the work process (McCleneghan Smith & Clark, 2007). Focusing on three distinct research inquires—the interplay of the libraries’ services, facilities, and digital presence—the librarians organized participatory design sessions aimed at bringing students directly into the design process of the library’s digital services. The authors explain that typical design approaches bring users in at the end to make comments on the prototype, but participatory design is about bringing them in from the beginning. The workshops allowed students to design their ideal library webpage and offered a glimpse into the way students were using the web services (McCleneghan Smith & Clark, 2007, p.125). Some key findings from this section of the research study concluded that students desired a high level of personalization in the library web services; they wanted to link to their professors, their grades, their courses, and wanted everything centralized in one portal (McCleneghan Smith & Clark, 2007, p. 38). By conducting the participatory design workshops the librarians realized that the library’s web services were designed around the library instead of around the students. These takeaways went into forming the redesign of the library’s website (McCleneghan Smith & Clark, 2007, pp. 38).

The last several examples make it clear why integrating local knowledge and human experience into any development process or service is imperative. Not only are new, critical perspectives introduced and learned from but the solutions become more likely to have long-lasting relevance because they come from within. Libraries looking to more inclusive, long-lasting services can begin with the co-creation approach, viewing it as part of the bigger goal of building a transformational learning ecosystem.

In contrast, when services are designed by departments from pre-determined agendas and then dropped on users for testing it is likely that the results will be short lived. In Roland Bunch’s Two Ears of Corn (1982), he recounts the story of El Naranjo, Columbia, a village on the Cauca River that received a thresher, huller, motor, and tractor to help with rice production. Returning six years later to assess progress, Bunch found a “virtual graveyard of rusting equipment and abandoned hopes” (Bunch, 1982, p. 11). Given the diversity of environmental conditions, cultures, communities, and agricultural production around the world, it is unlikely that transfer technologies—that is, transferring pre-determined technologies or information onto communities for the purpose of development—is an effective approach to making a difference in the lives of farmers. As Bunch (1982) describes at length, these transfer technologies have shown to hamper the ability of people to solve their own problems because they foster a false idea that local challenges are solved through charity. Furthermore, they incite a sense of inadequacy that can lead to chronic interdependence or loss of self-respect—as it can with non-traditional or first-generation college students. What’s clear is that any solution or service must be part of a process, and that process is most effective when initiated and managed to varying extents by users or library patrons—or in this case farming communities. This is because user communities are able to convey a range of experiences that make up a complex environment of interconnected components. When a solution or service is developed and tested outside of that context, in a silo, from the top, or with a pre-determined agenda or policy, those critical perspectives are left out and the service is less effective. For example, when computer time limit policies are created by administrators based on the perception of traditional users, they may not work for homeless users or older patrons with limited computer skills. Further, in addition to creating more inclusive services, libraries must embrace their role in the larger learning ecosystem; viewing themselves as integral, inspiring places where educational—and even social—transformations can take place.

Methods Applied

The Library for Food Sovereignty

Now I’d like to turn our attention to the case study of the Library for Food Sovereignty, tracing the processes that were nurtured to tease out the final product. As stated in the beginning of the paper, I will illuminate the processes and what was learned, and only at the end discuss the final interface. But let us keep in mind the initial question: how can we support and accelerate the peer-to-peer learning process of smallholder farmers in East Africa so that they can create a healthier and more just food system?

Development of the Library of Food Sovereignty began in 2015 and was inspired by the ingenuity of smallholder farmers in the Global South. A Growing Culture, the organization responsible for the project, saw an opportunity to support the work that organizations and groups were doing in participatory innovation development, an approach that evolved from participatory technology development to encompass the socio-organizational arrangements of farmers that extended beyond just technology (Wettasinha, Wongtschowski, & Waters-Bayer, 2008, p. 5). In many ways, this integrated approach includes the socio-cultural dimensions of natural resource management—harmonizing with A Growing Culture’s bottom-up work with farmers. The organization was founded in 2010 and for nearly five years conducted almost exclusively in-field projects aimed at nurturing local solutions to farming challenges. The Library of Food Sovereignty was born from this work and has become a multi-stakeholder and community-led effort to share and celebrate local farming knowledge.

As seen in some of the examples of farmer innovations above, local solutions often address a myriad of challenges specific to a community or geographical context that top-down solutions cannot. What’s more, the conditions and needs of people are constantly changing; so, it makes sense to start with the farmer so we can identify, first hand, primary concerns and priorities from a local perspective before implementing a development agenda. The Library of Food Sovereignty is an attempt to do just that: share and celebrate the potential of local solutions to contribute to solving some of the world’s most complex challenges such as climate change, poverty, gender inequity, and more. It demonstrates that some of the most effective solutions come from the grassroots and hold an important place even in an age of increasingly advanced technologies.

Problem Presentation: The Industrial Food Paradigm

Industrialized systems of producing food are ruining the environment and devastating local agricultural communities. Corporate agriculture produces at least one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions and depletes Earth’s precious resources at an unprecedented rate (Alexandre, 2015). The damage is immeasurable: depleted water supplies, eroded soils, poisonous chemical fertilizer runoff, loss of biodiversity, worsening of climate change, and ongoing hunger. What’s more, these one-size-fits-all methods lock farmers into relationships of interdependence because they are forced into monocropping, buying proprietary seeds year after year, and chemical inputs to keep this process going. Local innovation, a centuries-old farming tradition, is stifled.

And yet 70 percent of the world’s food still comes from small-scale producers primarily located in the Global South (Altieri, Funes-Monzote, & Peterson, 2011, p. 3). These resource-poor farmers are some of greatest stewards of biodiversity because they save and pass down seeds (ETC Group, 2017), and their diversified techniques regenerate soils, increase carbon sequestration, promote good relationships between men and women, and nurture local traditions. Even while the cards are stacked against them, they continue to regenerate ecosystems and enhance the wellbeing of communities and the life web. The Library of Food Sovereignty is a community working to support and accelerate the potential of local farming communities around the world, to “tip the balance” in their favor.

Peer-to-Peer Relationships

The story of the Library of Food Sovereignty is rooted in participatory technology development traditions that prioritize co-creation and peer-to-peer relationships between farmers, researchers, and development workers. A Growing Culture focused strongly on community building activities and personal relationships from the beginning. Starting in 2015, we began to mobilize diverse agrarian grassroots groups that worked in or around these traditions. These groups included farmer-led organizations and agricultural networks (often working through informal, non-binding alliances and interest groups) such as Prolinnova (PROmoting Local INNOVAtion in ecologically oriented agriculture and natural resource management), Pelum Africa, the Arid Lands Information Network, Africa Rural University, and the Farmer-Led Innovators Association of Kenya among many others.

These relationships often began with Skype calls and expanded into friendships and deeper professional alliances. These communities are now in the process of coming together to form a community of practice around the project. Members join because they care about participatory approaches and because they see an incentive to share and build upon the work they do in innovation development. Peer-to-peer relationships were a key aspect of our ability to form a strong-knit community; crucially, we had to make a conscious and systematic effort to create opportunities for including some of the marginalized groups we engaged. In some cases, this meant bringing a translator in so that we could have more meaningful conversations with certain farmers. In other cases, it meant exploring alternative media for communications such as radio and photographs.

This same kind of peer-to-peer relationship building can happen in traditional libraries in a variety of ways. Library human resources departments can make a conscious effort to hire staff from surrounding communities so that patrons see themselves reflected in the institution; library staff can be trained on how to appropriately get user feedback in creative ways; or libraries can engage community members around specific event planning or roundtables.

At A Growing Culture, we ultimately determined that the most effective way to kick-start the development of the Library for Food Sovereignty was to bring the community together, in person, at a stakeholder meeting to design and launch the project as a group.

On-Site Engagement

In September of 2016, we organized an international stakeholder gathering in the rural Ugandan village of Kasejjere in Kikandwa sub-county. Forty-five diverse delegates from seven countries attended. We brought together diverse groups of farmers to ensure multiple perspectives and inputs would be included in the planning and feedback (fig. 1). These included women farmers, indigenous farmers from Uganda, Burundi and Kenya, men and women delegates from farmer-led organizations, various types of food producers including livestock, vegetable, grain, forest keepers, beekeepers, and young and old farmers from both arid and more fertile geographies (A Growing Culture, 2016).

Figure 1. Group photo of farmers and delegates in Kasejjere, Uganda, in September 2016 for the Library for Food Sovereignty International Stakeholder Gathering. Not all delegates were present for the photo.

Figure 1. Group photo of farmers and delegates in Kasejjere, Uganda, in September 2016 for the Library for Food Sovereignty International Stakeholder Gathering. Not all delegates were present for the photo.A participatory workshop was designed with input and leadership from delegates and farmers at every step. This process was successful even though the participants had very little experience in libraries and many did not have regular access to the internet or computers. The location was decided upon based on the importance of on-site collaboration with stakeholders. This proved to be incredibly effective. Not only were participants surrounded by the innovative farmers of Kasejjere, but everyone got to know each other and form a strong community around the project. In contrast, most international conferences are held in hotels located in or around urban centers in Africa. While this might be easier from a logistical standpoint, it is a missed opportunity to strengthen community bonds and leverage diverse perspectives. The intimate, on-site setting of the Uganda summit allowed for a truly bottom-up approach to design, creation, and sustainable growth. This example builds upon the importance of community and human relationships in integrated service assessment and service design in libraries. If patrons feel they are more than just users of a service—they are active members of the library community helping to shape its culture—there is evidence as shown in this case study that overall functionality will improve.

Prototyping Process

Before the gathering, we conducted touchpoint calls with attending delegates to help set the meeting’s agenda and begin expanding or establishing new relationships with stakeholders. While it took extra time, and not all attendees were available for calls, it set the groundwork for a participatory and inclusive gathering in Uganda. Our staff got to know some of the delegates and farmers attending and we had a chance to get a preliminary idea of the needs and priorities of the community. The information gained from the “needs assessment” went into designing a participatory agenda for the summit. The benefits were twofold: we were able to kick-start the relationship building and also get insights into how we could most effectively use the time in person.

While together with the community in Uganda we ran some initial user mapping. We designed this process based around theater roleplay where farmers and delegates acted out how they might access, contribute to, and interact with the Library for Food Sovereignty (A Growing Culture & CauseLabs, 2016, slides 8-11). Farmers and delegates broke into groups and were asked to create a short skit that explored these three processes. Everyone enjoyed this exercise and took it seriously. The farmers and delegates illustrated a variety of challenges and opportunities relating to how they might discover that the library existed, how they would learn to use it, and what the incentives to contributing might be (fig. 2).

Some of the indigenous farmers imagined that they would learn about it from the Chief who had heard that such a platform could bring benefits to his community. One farmer illustrated learning about it from his children who had cell phones and were more connected to cities. The organization delegates acted out some challenges of presenting the technology in a respectful way and not imposing a new product or tool on a farmer in a condescending manner. Many insights were gained from this exercise that touched on the diverse and unique needs of stakeholder group. For A Growing Culture this exercise was invaluable: we gained a deeper understanding of some of the practical challenges to access and cultural and ageism barriers still very much a reality of the majority of our community.

Key Takeaways from Uganda Summit

Access Challenges

During the theater roleplay exercise, all groups indicated that access was likely the biggest challenge to being able to effectively use the Library for Food Sovereignty. Access to the internet and a computer was an issue, but so was getting access or obtaining equipment for photographing or recording their innovations and stories (A Growing Culture, 2016). All the farmers determined that they would most likely be able to use the library through a third-party mediator, such as a local organization. This revelation significantly influenced the design of the library platform. In the West, we don’t usually think about access as a challenge, especially in academic libraries, and yet it is. Bringing the library community together to discuss these issues could help illuminate the challenges of specific patrons, such as homeless and elderly users. Not all of the specifics will necessarily surface in a gathering; but the conditions can be nurtured for open dialogue and trustful relationships.

Not All Innovations are Technical

One big takeaway was that many innovations were addressing not only technical challenges but also socio-cultural dynamics of farming (A Growing Culture, 2016). These struggles—whether it was to overcome age barriers between generations as in one case or to address gender disparities between men and women in rural Uganda in another—illustrated the diversity of issues that smallholder farmers face.

These innovations, specifically the ones that affronted ways for resolving socio-cultural challenges, often took the form of inspiring stories. These stories had the potential to stimulate the innovation process and in that sense, were a key part of the project’s ability to support farmers to create a healthier and just food system. This takeaway also had a big influence on how the library interface was structured moving forward (fig. 3).

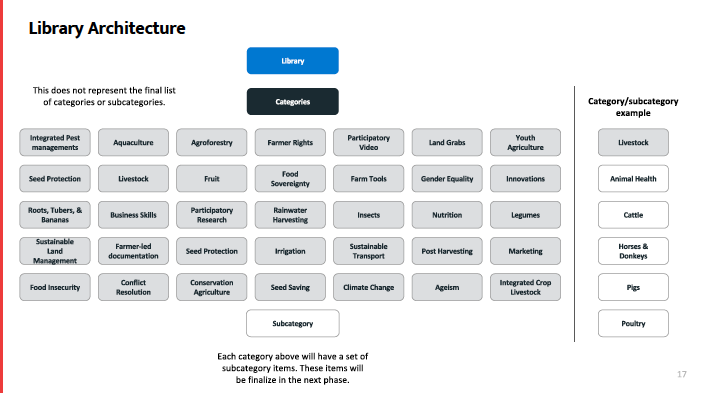

Figure 3. The library’s architecture. Categories include socio-cultural subjects like “ageism” and “gender equality.”

Figure 3. The library’s architecture. Categories include socio-cultural subjects like “ageism” and “gender equality.”This revelation is very relevant in traditional libraries where service designers tend to focus on technical challenges. Libraries might find when they explore some of these participatory approaches that relationship or power dynamics between patrons and library staff surface.

Open Access Complexities

Many of the indigenous farmers expressed distrust and reluctance to openly sharing their knowledge and innovations. Open access, which promotes information that is online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions, has largely come to be considered a public good in the West. But the idea of open access was not accepted as a positive to all Library for Food Sovereignty communities.

Distrust of open access generally comes from decades of knowledge misappropriation and misuse tangled in long histories of social injustice and colonialism (Bowrey & Anderson, 2009, pp. 480–481). While open access provides an unprecedented opportunity for sharing ecological farming methods it is also a challenge. A Growing Culture is a strong supporter of the open access movement; in fact, we routinely promote open sharing as not only an effective way to stimulate innovation but also as a potential approach to resisting top-down development and industrial agriculture. After the revelations that large parts of our user community felt uncomfortable with open access, we decided to re-evaluate this aspect of the project. We also realized that the on-the-ground learning was just as important as ever, and that those groups had to be included in creative or alternative ways in the library.

Soon after the gathering we drafted a working list of reasons to share and reasons not to share and started passing it around to our partner communities for feedback. This process was helpful as it started a dialogue around these tensions and allowed new ideas to surface. These revelations might not have surfaced had we not brought users into the design process from the beginning. In fact, we could have further marginalized an entire community from the project.

Library Interface

Now I will discuss how the information gathered using the participatory approaches went into forming the library interface. In its most basic form, the Library for Food Sovereignty is an online knowledge commons of local farming knowledge. But as you have read, the community is both online and offline. A Growing Culture, while developing the online platform for digital users, continues to nurture the on-the-ground peer learning aspects of innovation development. Many participants at the Uganda Summit praised the proposed name “Library for Food Sovereignty” as a library is generally seen as being a physical place welcome to all.

Clickable Prototype

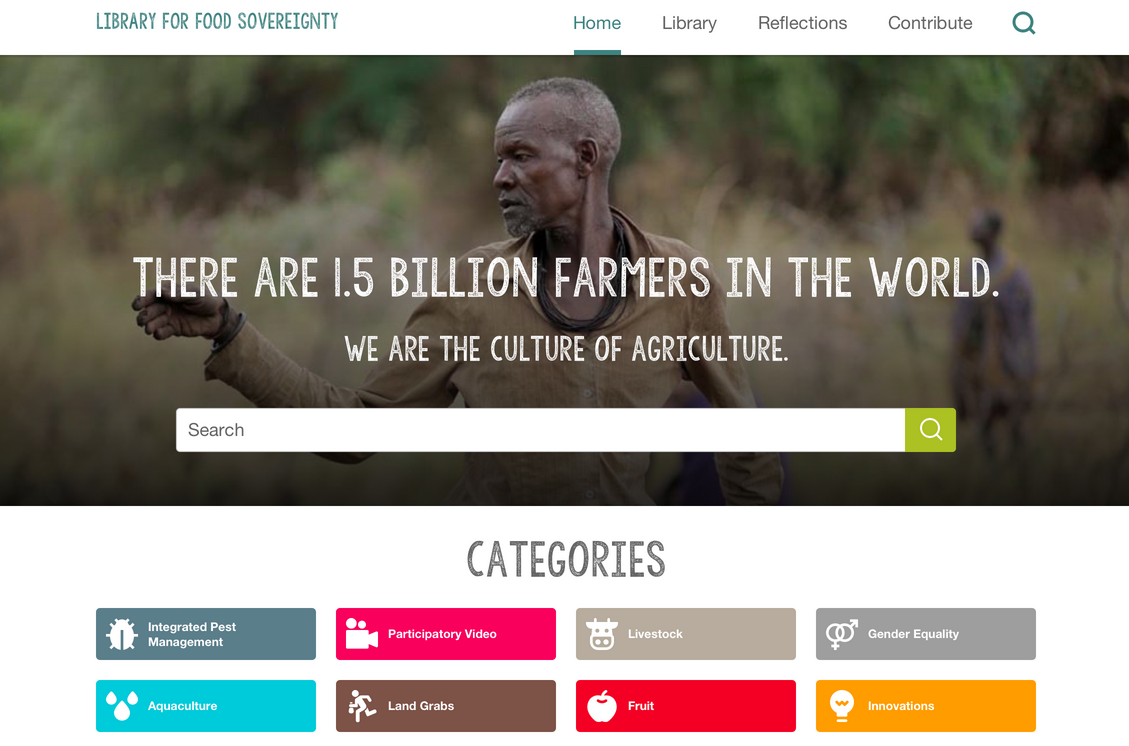

The information we gathered at the stakeholder gathering went into creating a clickable prototype of the library interface (fig. 4). In the months following the Uganda meeting, we continued to engage stakeholders via live feedback sessions on Skype, email, and private conversations. There were several key follow-up meetings to discuss progress on the design and development of the library. Stakeholders got a chance to click through, review the prototype, and leave comments. Most of the stakeholders that gave feedback were from the farmer organizations where they had relatively easy online access.

Figure 4. A snapshot of the top part of the library homepage prototype. Not all categories are represented in the image.

Figure 4. A snapshot of the top part of the library homepage prototype. Not all categories are represented in the image.Access was flagged as a serious challenge for the project. We spent a significant amount of energy reflecting on who was the primary user, or first-step user, of the library. Eventually we concluded that we would focus on creating a first-version of the commons aimed at the farmer organizations that had personal relationships with the rural farmers. From this decision, we designed a template for organizations to use when submitting local innovations from their communities. The template allows organizations to create a profile and upload and edit materials together with a staff member of A Growing Culture before the innovation goes live on the platform. It also allows the organizations to assist individual farmers in setting up profiles of their own. We discussed future possibilities of creating more robust support systems for organizations, such as the possibility of renting out equipment to photograph or video local innovations and stories in the field.

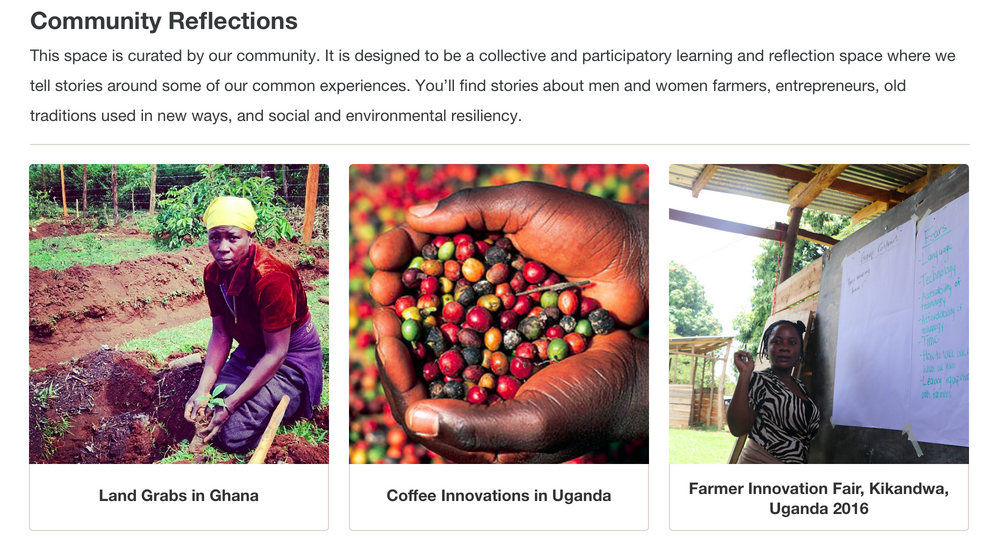

The crucial revelation that not all local innovations addressed technical challenges of farming led us to design a section called “reflections” where communities could share their stories (fig. 5). This section could be curated around themes such as “land rights” or “Indigenous land management” or “food sovereignty.” Additionally, we developed a tagging/naming system where categories and sub-categories were not limited to technical terms such as “beekeeping” or “agroforestry” but also “gender equity” and “young farmers.” We considered this essential because the stories of overcoming hardship oftentimes catalyzed an innovative process in communities and inspired others.

Figure 5. A snapshot from the clickable prototype for the Community Reflections page. This is a collective space where farmers can share their perspectives and stories.

Figure 5. A snapshot from the clickable prototype for the Community Reflections page. This is a collective space where farmers can share their perspectives and stories.The pilot of the Library for Food Sovereignty will be open to all, but the conversation around the sensitivities to open access are not over. A Growing Culture is working closely with indigenous communities to find ways to support knowledge exchange in communities that do not want to share openly online.

Conclusion

The participatory technology development approaches provided an effective framework for our organization as we developed the Library for Food Sovereignty platform, an online knowledge commons for smallholder farmers to share local innovations. The library is an information resource and digital tool to support smallholder farmers so that they can help shape a more healthy and fair food system. The participatory approaches used during the design process—such as an on-site gathering in rural Uganda, theater roleplay, inclusion of indigenous farmers, and ongoing engagement with the stakeholders—are helping to create an inclusive and functional platform. Beyond inclusivity and functionality, however, the processes explored during the design period transformed the learning ecosystem to one that was developmental on its own. These processes can be explored in traditional libraries as approaches to engaging marginalized patrons, but also to awaken the library as a place of collective learning and relationship building. As libraries consider participatory approaches to engaging users in the design process of services and information tools, they can draw from the findings of the Library for Food Sovereignty case study to improve the learning ecosystem all together.

References

- A Growing Culture. (2016). Library for food sovereignty stakeholder gathering report, September 19-22, 2016. A Growing Culture and Kikandwa Environmental Association.

- A Growing Culture and CauseLabs. (2016). Library for food sovereignty blueprint & roadmap. A Growing Culture and CauseLabs.

- Altieri, M., Funes-Monzote, F.R., & Peterson, P. (2011). Agroecology efficient agriculture systems for smallholder farmers: Contributions to food sovereignty. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 32(1). pp. 1–13.

- Alexandre, N. (2015). The carbon price of agriculture. Environmental Performance Index: The Metric. Retrieved from http://archive.epi.yale.edu/the-metric/carbon-price-agriculture

- Araya, H., Tebari, K., HaileSelassie, L., and Redehay, A. (2010). Farmer-led adaptation of local water-management innovation in Ethiopia. Farmer-led Joint Research: Experiences of Prolinnova Partners. A booklet in the series on Promoting Local Innovation (PROLINNOVA). Silang, Cavite, Philippines: IIRR / Leusden: Prolinnova International Secretariat, ETC EcoCulture. pp. 44–52.

- Bowrey, K., & Anderson, J. (2009). The politics of global information sharing: Whose cultural agendas are being advanced? Social & Legal Studies, 18(4) 479–504. doi: 10.1177/0964663909345095

- Bunch, R. (1982). Two ears of corn: a guide to people-centered agricultural improvement. Oklahoma City: World Neighbors.

- ETC Group. (2017). Who will feed us? The industrial food chain vs the peasant food web. Retrieved from http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/etc-whowillfeedus-english-webshare.pdf

- Hawken, P. (2017). Project drawdown. New York: Penguin Random House.

- Heath, P. J. (2014). Service design for libraries. Presented at the libraries@cambridge Conference 2014: Quality, Cambridge, England. Retrieved from http://libatcam.blogspot.com/2013/01/service-design-for-libraries.html

- Magagi, S., Diop, J. M., Toudou, A., Seini, S., and Mamane, A. (2010). Joint experiment to improve a local fish-smoking oven in Niger. Farmer-led Joint Research: Experiences of Prolinnova Partners. A booklet in the series on Promoting Local Innovation (PROLINNOVA). Silang, Cavite, Philippines: IIRR / Leusden: Prolinnova International Secretariat, ETC EcoCulture. pp. 35-43. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235632902_Trying_out_joint_experimentation_in_poultry_farming_in_Uganda_an_experiment_in_itself

- Mager, B., & Sung, T. J. (2011). Special issue editorial: Designing for services. International Journal of Design, 5(2). pp. 1–3.

- Marquez, J., and Downey, A. (2015). Service design: An introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave Journal of Library User Experience, 1(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.201

- McCleneghan Smith, J., and Clark, K. (2007). Dream catcher: Capturing student-inspired ideas for the libraries’ web site. In N.F. Foster and S. Gibbons (Eds.), Studying students: The undergraduate research project at the University of Rochester. (pp. 30-39). Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1802/7520

- Polaine, A., Løvlie, L., and Reason, B. (2013). Service design: from insight to implementation. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfeld Media.

- Veldhuizem, L, Water-Bayer, A., and de Zeeuw, H. (1997). Developing technology with farmers: A trainer’s guide for participatory learning. New York: ZED Books Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.prolinnova.net/sites/default/files/documents/resources/training-mats/developing_technology_with_farmers.pdf

- Wettasinha, C., Wongtschowski, M., and Waters-Bayer, A. (2008). Recognizing local innovation: Experiences of prolinnova partners. Silang, Cavite, The Philippines: IIRR/Leusden: Prolinnova International Secretariat, ETC EcoCulture. Retrieved from https://www.prolinnova.net/resources/publications/Recognising local innovation