Toward a More Just Library: Participatory Design with Native American Students

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article provides a brief history of participatory design and an overview of its principles, followed by a discussion of participatory design as an apt methodology for building a more justice-oriented library. To illustrate the practice of participatory design, the article includes an in-depth description of a participatory design case study in which Native American students and a librarian co-created a new community outreach tool for a library at mid-sized public research university. The article concludes with recommendations for library practitioners who wish to implement participatory design practices with Indigenous communities.

This paper was refereed by Weave's peer reviewers.

Introduction

Participatory design is a socially-active, politically-conscious, values-driven approach to co-creation. The need for participation recognizes that imbalances of knowledge and power exist among different people and groups within an organization (Kensing & Greenbaum, 2013). Participation in design is about seeing the imbalance of knowledge and power where it exists, and working toward a more just balance.

To accomplish this goal, participatory design aims to establish a creative space for users and designers where principles such as power sharing, knowledge exchange, and self-representation can be realized and put into practice. Through participation in design, the users of a service are given equal voice in the design of that service. Pragmatically, participatory design can lead to better user experiences and better services, since those who will use and experience a service are able to provide essential direction in its design. Politically, it calls for an attunement to existing power dynamics within an organization, and seeks to rebalance power with a view toward the traditionally marginalized, underrepresented, and oppressed. As an approach that seeks to interrogate prevailing power structures, challenge dominant narratives, and address existing social inequalities, participatory design can serve a mission of decolonization. When a project includes Indigenous peoples who are understood, respected, and empowered as self-determining storytellers throughout the design process, participatory design can function as an indigenizing process that ultimately improves the lives of all participants.

In this article, we provide a brief history of this approach and an overview of its principles, followed by a discussion of participatory design as a methodology for building a library that is more empathetic, just, and inclusive—a library that deserves Indigenous students. The centerpiece of the article is an in-depth description of a participatory case study in which Native American students and a librarian co-created a new community outreach tool for a library at mid-sized public research university. Through this participatory design approach, the voices of Indigenous students were integrated into decision-making processes of the library. We conclude with recommendations for library practitioners who wish to implement participatory design practices with Indigenous communities.

Concept Overview

Origins and Principles of Participatory Design

Participatory design traces its origins to 1970s Scandinavia, where democratic values merged with labor movements and systems design in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (Robertson & Simonsen, 2013). Early projects involved trade union workers (Nygaard & Bergo, 1975), newspaper employees (Ehn, 1993), and nurses (Bjerknes & Bratteteig, 1987; Kensing & Greenbaum, 2013). In addressing labor relations and workplace power dynamics, participatory design demonstrated and pioneered the involvement of the user in the design process, and established itself as a socially-active, politically-conscious, values-based design discipline. These early projects emphasized that the skills of users and designers are equally valuable, and that participation in design is fundamentally a learning process in which designers and users learn from each other and grow together. This co-creative process leads not only to a superior product, but also contributes to a more just and democratic culture.

Participatory design coheres around a set of principles that provide a direction for the approach (Iversen, Halskov, & Leong, 2012; Frauenberger, Good, Fitzpatrick, & Iversen 2015). The values of the approach represent characteristics of the type of world that participatory design seeks to create, and helps guide the discipline's social activism and political consciousness. In this section, we briefly describe eight leading principles of participatory design: participation and representation, shared power, equal expertise, mutual learning, co-creation and co-determination, democracy, justice and social activism, tools and techniques.

Participation and Representation

Participatory design begins with participation, where the researched transcend to a position of trusted and legitimate participant in the research and design process. This is more than one-way input to be analyzed later in a process ultimately controlled by the designer or the researcher. Evidence and decisions are generated in sincere collaboration, where the researched have genuine representation during the full duration of the process (Kensing & Blomberg, 1998; Bratteteig & Wagner, 2014a; Bratteteig & Wagner, 2016a; Collins, Cook, & Choukier 2017).

Shared Power

Shared power means using our privileged position to empower those who may be invisible or weaker in societal and organizational power structures, with the goal of co-creative social transformation (Eubanks, 2009; Bratteteig & Wagner, 2014a).

Equal Expertise

When expertise is accepted as equal, we can involve the skills of both users and designers (Ehn, 1993). We acknowledge community members as experts in their own situations (Bannon and Ehn, 2013).

Mutual Learning

Mutual learning happens when participants share perspectives and grow knowledge together. When expertise and viewpoints are exchanged and combined, social barriers are broken down, and new insights are able to emerge toward productive, culturally-appropriate ends (MacTavish et al., 2012; Kapuire, Winschiers-Theophilus, & Blake, 2015).

Co-creation and Co-determination

Through this process, community members and designers create the design product together, and work collaboratively to shape a shared future (Moll, 2010; Bannon & Ehn, 2013).

Democracy

Participatory design is strongly guided by a political sense of democracy. This means the right to have a voice, and the right to have your voice matter, especially from voices traditionally unheard (Bjerknes & Bratteteig, 1995; Bødker & Zander, 2015).

Justice and Social Activism

Participatory design is politically conscious, justice oriented, and socially active, working to address and reconfigure structures that perpetuate inequality among social groups and oppression of marginalized peoples (Holmlid, 2009; Choudry, 2013; Wallerstein et al., 2017).

Tools and Techniques

To put these principles into practice, participatory design draws from a toolbox that includes a variety of flexible, collaborative tools to elicit creative and critical thinking: scenarios, mock-ups, workshops, design games, and prototyping (Brandt, Binder, & Sanders, 2013). These tools and techniques help participants express their current needs and future visions (Kensing & Greenbaum, 2013).

Participation as an Approach for Building a Justice-oriented, Inclusive Library

Participation and Power

The main approach in participatory design has been about paying attention to power relations within an organization, and providing resources with a view to the empowerment of traditionally marginalized groups (Bannon & Ehn, 2013; Rodil & Winschiers-Theophilus, 2015). The approach has strong connections with human-centered design (IDEO, 2015), participatory action research (Giesbrecht, Miller, Mitchell, & Woodgate, 2015; Bocci, 2016; Rowell & Hong, 2017), and community-based participatory research (Banks et al., 2013; Kia-Keating, Santacrose, Liu, & Adams, 2017), disciplines which also focus on user needs, activism, justice, and community impact via participation in design. In seeing the world through a lens of justice, the Scandinavian tradition of participatory design shares a common purpose with decolonization and indigenization. Decolonization and indigenization are complex, multifaceted concepts that challenge Western people to look inward and backward in a process of critical self-reflection, and then to look forward and actively work to build a future where Indigenous people are understood and respected.

Decolonization

Decolonization seeks to critically interrogate and dismantle oppressive and exclusionary structures of colonization that continue to harm Indigenous communities today. Decolonization seeks ultimately to improve the social and material conditions of Indigenous peoples. In response to centuries of inequality, decolonization works to create space in everyday life, research, academia, and society for Indigenous perspectives and peoples to flourish. (Kovach, 2009, p. 83). Within the contexts of research and design, decolonization can be advanced when the researched participate in the research process, and when researchers become activists dedicated to social transformation (Chilisa, 2012, p. 227). The intentional act of decolonization in research and design therefore calls for greater and more meaningful power sharing and participation with traditional oppressed Indigenous peoples, with outcomes that serve Indigenous communities both practically and politically.

Indigenization

Indigenization happens when Indigenous ways, perspectives, and worldviews have the space to be influential and to thrive. Within the context of research and design, it requires a sensitivity to Indigenous cultures and an active promotion of Indigenous participation and ownership of the research and design process (Chilisa, 2012, p. 101). Indigenization can be advanced by incorporating Indigenous inquiries and knowledges into Western practices and institutions, such as the design of a library.

Seeking Justice through Participatory Design

To properly frame the connection between participatory design and Indigenous methodologies, one must first acknowledge that any understanding of Indigenous approaches alongside Western-constructed research processes calls to mind the long history of oppression and mistreatment of Indigenous communities by the hands of Western researchers (Kovach, 2009, p. 28). Given the extractive, exploitive history of research within Indigenous communities, non-Native researchers today must start from a place of respect and thoughtfulness for Indigenous cultures and knowledges, and work to mitigate power differentials in all aspects of research, with results encompassing both practical and political considerations (Kovach, 2009, p. 122). The focus on practical and political outcomes represents a fulcrum point between participatory design and Indigenous methodologies, as participatory design also posits dual outcomes that are practical and political. The pragmatic rationale for participatory design argues that users and designers need to learn together to find the most desirable and feasible solutions; the political rationale takes an ethical stance that the voices of marginalized communities need to be heard and heeded in decision-making processes that will affect them (Robertson & Simonsen, 2013; Barratt and Maddox, 2016).

For participatory designers and Indigenous researchers alike, the practical and the political objectives are united around the common theme of empowerment through participation. Within a participatory design paradigm, power is realized when the participant possesses the ability to create choice and determine decisions (Bratteteig and Wagner, 2014a). Within an Indigenous paradigm, power is also framed around participation, and is realized when the participant becomes a storyteller (Kovach, 2009, p. 121). Through a self-determined, interpretive tradition, Indigenous story offers knowledge relevant to one’s own life in a personal, particular way. The act of self-determination is central to Indigenous research approaches (Smith, 2012, p. 121, p. 144). The self-determining Indigenous storyteller is therefore essential for any participatory Indigenous inquiry. When we empower the Indigenous storyteller as a self-determining research participant who possesses the ability to create choice and determine decisions that ultimately improve their lives, we are in some measure decolonizing and indigenizing our research processes and our practice areas. The challenges of achieving broad change in thought and action are daunting. But on a small scale and within our own organizations, we can create and model a more just, participatory world that understands, respects, and includes Indigenous peoples.

Service Design, Participatory Design, and Social Justice in Libraries

Participatory design represents an extension and deepening of more established design disciplines within libraries, such as service design. The approach shares many tools and techniques with service design, such as journey mapping, expectation maps, prototyping, and journaling (Marquez & Downey, 2015; Marquez & Downey, 2017). As a design discipline concerned with the subjective experiences of users, service design also shares a number of values with participatory design, such as empathy, a focus on user needs, open-mindedness, and co-creation (Marquez & Downey, 2016, pp. 13–32). In sharing these tools and values, the two approaches can be complementary (Steen, Manschot, & de Koning, 2011; Johnson, 2015; Trischler, Pervan, Kelly, & Scott, 2017). Participatory design differs in that it is a political process as much as a design process, focusing equally on creating better designs and better social conditions for the participants. The emphasis on political outcomes has traditionally distinguished participatory design from the more pragmatic service design. More recently, however, service design projects have taken on a greater political consciousness (Holmlid, 2009; Dietrich, Trischler, Schuster, & Rundle-Thiele, 2017; Sundström, Karlsson, & Camén, 2017).

As a practice of its own, participatory design has seen expression in libraries (Costantino et al., 2014; Watkins & Kuglitsch, 2015; Ippoliti, Nykolaiszyn, & German, 2017). A report on participatory design in libraries from the Council on Library and Information Resources (2012, p. 2) notes that it can be challenging for faculty members, university staff, undergraduates, and graduate students to contribute their specialized knowledge to the process of building library spaces, services, and tools. Through a series of project overviews, the report presents the case that participatory design makes it possible for diverse stakeholder groups to communicate and co-create productively in a library environment. Wood & Kompare (2017) similarly applied this approach to develop shared vision with users, enhance communication across stakeholder groups, and increase user advocacy. Many of these examples of participatory design in libraries focus on practical outcomes for users in the library; few place an equal focus on the social and political outcomes for participants in the larger world.

Our field is now ready to deepen existing service design and participatory design practices by awakening our political consciousness and committing to social justice. As Bech-Petersen, Mærkedahl, & Krogbæk (2016) say, “We believe the time is ripe to think beyond user involvement and also reflect on citizens and civic engagement at deeper levels of co-creation.” Indeed, participatory design makes it possible not only for multiple stakeholders to communicate, but also for multiple stakeholders to share knowledge and power with the justice-oriented mindset of social activism.

Others within the library profession have also advanced social justice initiatives, working to increase our critical self-awareness and political consciousness (Morales, Knowles, & Bourge, 2014; Brook, Ellenwood, & Lazzaro, 2015; Baildon et al., 2017; Hathcock, 2015). A variety of subdisciplines are also working to advance justice and decolonization, including critical information literacy (Saunders, 2017; Hathcock, 2017; Tewell, 2017), radical cataloging (Drabinski, 2013; Billey, Drabinski & Roberto, 2014; Dudley, 2017; Farnel et al., 2017), and activist and community-based archives (Caswell, 2017; Drake, 2017; Joseph, Crowe, & Mackey, 2017; Rolan, 2017; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, n.d.), and user experience (Harihareswara, 2015). In addressing questions of racialized power within libraries, Hudson (2017) argues that “to be included in a space is not necessarily to have agency within that space.” To be present is not the same as to participate. Genuine agency, self-determination, and participation is achieved when all those present are understood, respected, and valued as intellectual, creative, and influential contributors—especially from those traditionally excluded. The Design Justice Network (2017), articulates ten action-oriented principles for supporting social justice, including “Define a set of principles by which you will work;” “Design with, not for;” “Shape alternatives futures;” and “Begin by listening.” In sharing goals of justice and social activism, participatory design can complement and amplify related efforts across the field.

The case study presented in the next section is one small contribution to larger activist movements of decolonization and indigenization of research, design, and librarianship. As Smith states (2012, p. 210), “The activist struggle is to defend, protect, enable, and facilitate the self-determination of Indigenous peoples over themselves in the states and in the global arena where they have little power...activism begins at home, locally.” This case study represents a local effort to build a more just library for Indigenous students.

Participatory Design in Action: The User Experience with Underrepresented Populations Project

Project Overview

The User Experience with Underrepresented Populations (UXUP) project started with the idea that the library can better serve our university’s Native American community. The primary goal of the project was to empower Native students in the design of the library that they themselves would use. Through participatory design, the project created a space for Native American students to tell the story of their experiences at the university, to co-determine the design process, and to voice their concerns within the library.

UXUP focused on Native students on campus because this population is important to our state. Montana State University is a land-grant institution, and works to serve all populations of Montana. The land now known as Montana is home to many diverse communities of Indigenous peoples, including the Blackfeet, Chippewa-Cree, Salish and Kootenai, Crow, Assiniboine, A'aninin, Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and the Little Shell Chippewa.[2] Native American students from these Nations and many others around the region are a growing part of our campus’s population, and represents our university’s largest minority group. In 1979, MSU had 52 Native students, and in 2017 we have 712, now representing 4.5 percent of the total student enrollment.[3] MSU has made an institutional priority to engage with and support our Native community. With that in mind, the MSU Office of Provost sponsors an internal grant program called Native American Recruitment and Retention, which annually funds projects that focus on Native American student success. UXUP was developed as a response to this grant call, and was awarded $7,200.

The UXUP project supports Native student success two ways. First, it empowers Native students to be meaningful participants in the design of the library. Second, it presents a participatory methodology for creating socially-active and empathetic library service designs that respond to the real needs and priorities of Native students. Through the participatory design process of mutual learning and co-creation, participants were able to share expertise and grow as a group. In terms of a wider contribution to participatory design as a discipline, UXUP connects the Scandinavian tradition of participatory design with contemporary Indigenous methodologies that focus on Indigenous story and self-determination within a broader context of social justice.

Sustainability and Assessment

In terms of sustaining and measuring outcomes, participatory design focuses on both product and process. Products can include design artifacts and other practical outcomes, along with material and social benefits to the participants. From this product viewpoint, sustainability and assessment can be guided by questions such as, “how do we know that we improved the lives of the participants?” and “how can we ensure that participants enjoy lasting results?” (Iversen & Dindler, 2014). In complement to the products of participatory design, the process itself is also an outcome. From the process viewpoint, the principles of this approach—such as participation, mutual learning, co-creation, and power sharing—are realized through the actual practice of participatory design. A number of formal summative and formative assessment frameworks and guidelines have been designed to answer questions of assessment for participatory design (Bossen, Dindler, & Iversen, 2016). For assessing process and product for Indigenous participants and communities, an attunement to cultural sovereignty is especially relevant (Edmunds et al., 2013). Common methods include interviews, surveys, ethnographies, observations, and workshops, with the assessment focused on community impact, participant gains, patterns and depth of participation, and decision-making.

UXUP ultimately generated outcomes that were both product-oriented and process-oriented. With both product and process in mind, assessment for UXUP was approached through informal self-evaluations and unstructured interviews with participants. In this way, UXUP assessment itself was participatory.

In terms of product, the project produced a seven-part poster series and social media campaign in support of our university’s Native American population. Assessment for the design product itself is ongoing. Early indicators show that the poster series has been received positively. One of our key campus gathering spaces for Native students—the American Indian Center—has displayed our posters in a prominent place. The posters have also been presented at Native Pathways, one of our campus’ Native student orientations. Demonstration of acceptance is an important step in assessing this project. A tool or service such as the one produced by UXUP, which intends to support a specific user community, must first be accepted by the community. Acceptance also supports longer-term sustainability of the new tool. Assessment of the product will next turn to community impact. We hope to have follow-up evaluations once the tool has been in use for some time. This might include community dialogues around the tool or surveys about its perception and impact. A cohort study might also illuminate the tool’s impact. For a cohort study of UXUP, one group of students would take part in orientation programming with the poster series, and another group would not. We would then analyze the different behaviors of the cohorts, controlling for demographic and other factors. Does one group visit the library more often? Feel more confident and at home in the library? Is the tool a significant factor in any differences that emerge? These questions set the groundwork for future in-depth evaluations.

In terms of process, we created a safe design space where participants could share their views and create together. Over the course of the project, student participants reported increased feelings of comfort and capability within the library. The librarian also experienced increased levels of understanding and empathy towards the student participants. Engagement from all participants—both students and librarian—remained steady throughout the process, as measured by attendance and contributions. Self-evaluations and interviews indicated that student participants bonded during the course of the project, felt more empowered as Native students in the library, and indeed now use the library more often. With a view towards the principle of power sharing, the design practice of UXUP demonstrated a more participatory development of library services, with the voices of the student participants in balance with the voice of the librarian. This itself is a key measure of success for a participatory design project. We discuss our process and outcomes in greater depth in the dialogue below.

Dialogue Introduction

The following three sections present the story of UXUP. We discuss our project’s background and goals, the design process, and outcomes and reflections. These sections take the form of a dialogue between Scott Young, a settler and a librarian, and Celina Brownotter, a Hunkpapa Lakota/Diné student from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. Scott was the professional lead on the project, and Celina was the student lead. A dialogue approach allows us to clearly express our individual voices and experiences.

Background and Goals

Scott Young: We started UXUP to support and empower our community of Native students, and to explore participatory approaches to library design. The project recognizes that Native students are underrepresented and can often be marginalized.

Celina Brownotter: As a Native American student, I have at times felt isolated on campus and in the library, because of a lack of representation and sense of belonging.

SY: The UXUP project attempts to respond to those feelings of alienation by modeling a more representative, participatory process for making decisions about the library. By designing for the experiences of Native American library users, we can improve services for the Native community. And by bringing Native voices into the decision-making power structures of the library, we can begin to reshape the library with an activist view towards decolonization and indigenization. In elevating Native students to the position of equal participant in the design process, we can model a more inclusive approach for designing the library.

CB: As a student, I am not typically involved in the decision making process in the library. The politics and the decision-making process of the library are not really visible to me, yet I feel their effects every day because I use the spaces and services of the library.

SY: So the UXUP project aims to model a more just decision-making process by empowering a traditionally marginalized student population to make decisions about the library. In this way, UXUP is driven by two primary motivations. Practically, UXUP aimed to create a new community outreach tool that could help connect the library with the university’s Native population. Politically, UXUP asks critical questions about the library and presents a new way to design services that meaningfully shares power with the people who will use those services. UXUP helps form the foundation for more justice-oriented approach for library design, and will help sustain a longer-term relationship with our campus’ Native community.

Design Process

Our UXUP design approach can be categorized into three main stages (see Table 1).

- Stage 1: Explorative—exploring topics, concepts, and problems related to the experience of participants

- Stage 2: Generative—generating ideas and potential solutions around key topics explored in Stage 1

- Stage 3: Evaluative—evaluating and implementing the most desirable, feasible, and viable ideas generated in Stage 2

Stage | Purpose | Design Exercises[4] |

|---|---|---|

Stage 1: Explorative | In this initial stage, we discussed topics, concepts, and problems related to the life experience and library experience of participants. | Interviews Vision cards Great Pie Mind Map Build Your Vehicle |

Stage 2: Generative | In response to the key topics that emerge in Stage 1, we generated new ideas and potential solutions to the problems identified in the explorative stage. | Predict Next Year’s Headlines Collage Journey Map Value Curve Clockwise |

Stage 3: Evaluative | In the final stage, we evaluated the solutions generated in Stage 2. The ideas that were the most desirable, feasible, and viable were then prepared for implementation. | Club Members Smiley Voting Paper Prototyping Storyboarding Final design creation |

SY: In terms of scaffolding, our general approach for UXUP was to be flexible within a broad structure. The three-stage model presented above represents our broad structure. The individual exercises within each stage were determined through dialogue and consensus within the group (The exercises used during UXUP are described in full via the resources listed in the “Tools and Techniques” section below). As we moved through the exercises and the stages, we remained responsive to the evidence produced along the way. We met for weekly design workshops that took on a two-part structure: we first conducted and completed one or two exercises, then we reflected on and discussed the evidence together as a group. This approach helped create an open environment for participatory storytelling and shared decision-making.

To facilitate the process of selecting the exercises, Celina and I met additionally every week for in-depth analysis of the evidence produced through the exercises. We discussed the most appropriate next steps given what had been generated so far. The exercises in our process were all drawn or adapted from the design resources listed in the “Tools and Techniques” section below. We then presented informal reports to the group that summarized our progress and recommended one or two possibilities for subsequent exercises. I facilitated these conversations among the participants. As the library professional, I was conscious of my power and status in the group. Throughout the process I acknowledged my power vis-à-vis the students, with a view towards the power-sharing and co-creation principles of participatory design. I was careful to create space for the student voices and to meaningfully and equally integrate all of our viewpoints into the decision-making process. In practice, this meant that I had to listen closely to the students and remain attuned and responsive to their wants and needs. When there was disagreement, we continued our discussions until all participants were satisfied with the agreed-upon next step. For example, I had initially assumed that the group would ultimately generate a digital product in support of our Native population, such as a new web application that would reach and engage students. This assumption derived from my professional background and bias as a web-oriented librarian. The students, however, asserted through the design process that a poster campaign would be more effective for reaching the Native population. As we moved from Stage 2 to Stage 3, we examined the evidence together with our personal experiences and viewpoints, and agreed together that the printed posters would be a more effective engagement tool, and so the posters became the focus of our Stage 3 exercises.

Given the particular characteristics of the UXUP participants and population, the specific exercises that were appropriate for the UXUP group might not be suitable for different group of participants. However, the flexible three-stage model is applicable in a variety of contexts, and can be adapted for many different participant groups and user populations.

Stage 1: Topic Exploration

CB: We started with preliminary project meetings, where Scott and I worked on the scope and outcomes of the project.

SY: We met several times to talk through the history and approach of participatory design, and how we could apply this methodology within library and Indigenous contexts.

CB: Some of our early conversations of Indigenous contexts were about how does a Native American student connect to their cultural identity while immersed in a colonized academic environment, where the Indigenous perspective is often overlooked.

SY: To better understand the experiences of Native students on campus, we conducted interviews with Native American students that formed a foundation of understanding and empathy. We discussed goals, attitudes, frustrations, behaviors on and off campus. From these interviews, we identified key themes that helped shape the overall direction of the project.

CB: Some of the key themes that emerged from the interviews was a desire to return back to their tribal communities to help the people reclaim cultural identity and restore health. However, there was also a struggle that occurred during the first year when stepping foot into an academic environment that was overwhelming, intimidating, or unwelcome (see Table 2).

Interview Excerpt | Interview Excerpt | Interview Excerpt | |

|---|---|---|---|

Theme: Indigenous Identity and Community Contributions | Wants to go back home and restore health and reclaim cultural identity. | Wants to go back home and become the tribe’s attorney general. | Wants to go back home and become an educator on the reservation. |

Theme: Intimidation of Library Spaces and Services | First year, needed a friend as a guide to the library. Would not have approached the space themselves. | Felt out of place and uncomfortable in the library. Intimidated by the amount of people. | Students should be helped from the beginning. |

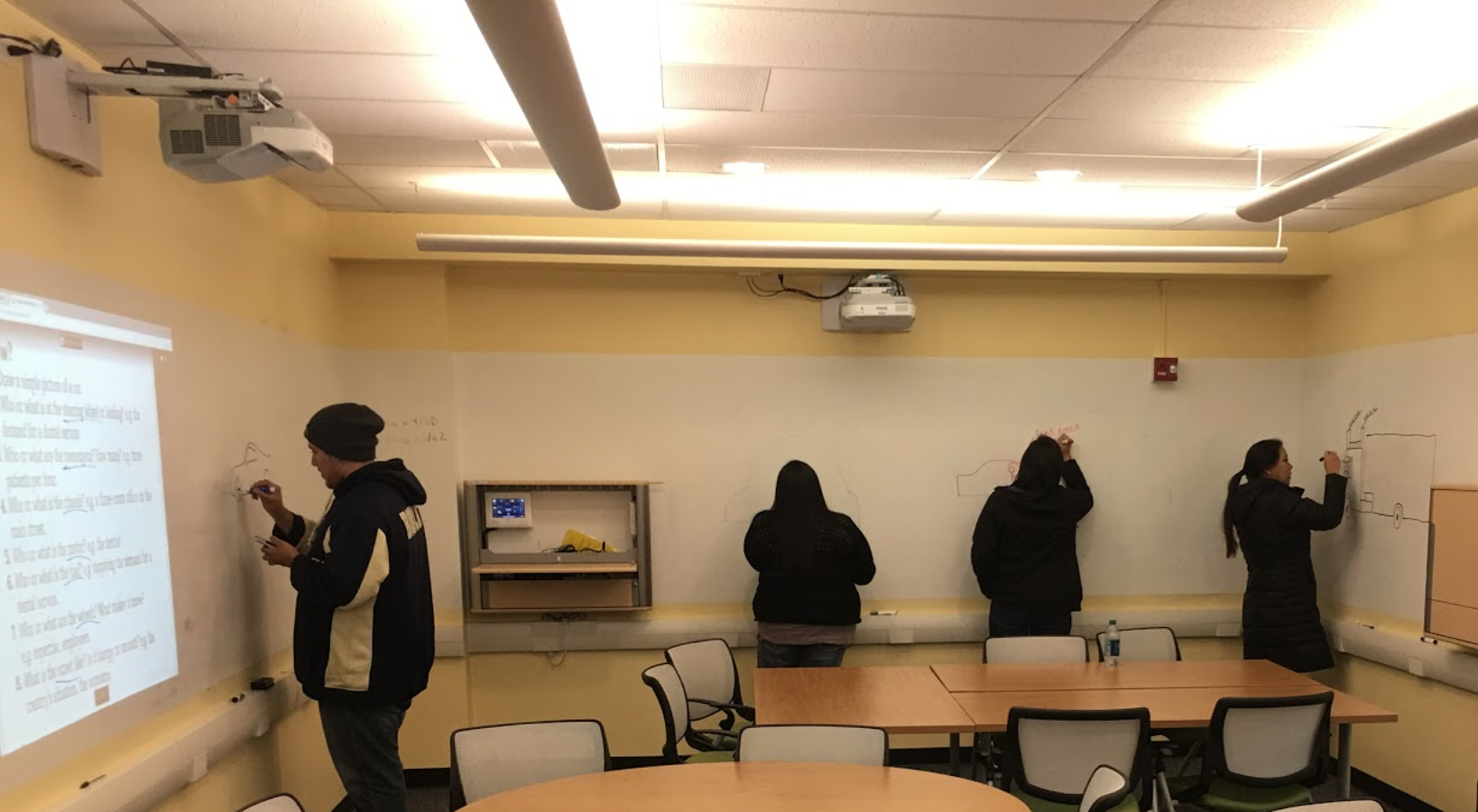

SY: To provide a structure for further exploring and addressing these issues, we then formed a “Participatory Design Group” comprised of four Native American undergraduate students, all of whom had completed interviews (fig. 1). At our first meeting, we discussed the interview results with the participants.

CB: A critical aspect of participatory design is to make the design space comfortable for everyone to contribute, which leads to a strong final product. The physical and mental design space that we created was supportive, open, and encouraging, so that it could be comfortable for everyone to contribute.

SY: We started with once-a-month meetings, but quickly learned that we needed more frequent meetings, so we adapted to a twice-a-week schedule. We met for a total of twenty hours over the course of the spring semester in 2017.

CB: We were able to have near perfect attendance throughout the semester. One reason for this is because students were paid a generous wage from the grant.

SY: It was important that the students be recognized and compensated for the essential labor and creativity that they contributed to the project.

CB: Our early workshops focused on introducing participants to the design process with exercises based around general life experiences and situations. We wanted to ease into the design process and explore general topics, and get to know our various backgrounds and experiences. Stage 1 exercises helped us illustrate the elements of our daily life to see where and how we spent our time. The goal was to see how we each saw the relationships and connections between services and resources of the library. Essentially, what was within each of our field of vision?

SY: For the first design stage, we applied four exercises that built on the interviews: Vision Cards, Mind Map, Time Machine, and Build Your Vehicle. For the sake of this discussion, we’ll highlight and describe key exercises that demonstrate our design process. One key exercise was the Time Machine, (fig. 2) which prompted us to mark the important elements of the journey that led to our arrival at MSU.

Figure 2. The Time Machine exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing key life events leading up to enrollment at Montana State University.

Figure 2. The Time Machine exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing key life events leading up to enrollment at Montana State University.CB: One student came to MSU directly from high school, but initially felt overwhelmed in an environment that was much larger than their rural home. This student left MSU in their first year and returned to their tribal college to earn an associate's degree, then returned to MSU to finish their bachelor's degree. For a Native student, it can be difficult coming from an area where your family is everywhere to being alone in a large academic environment. Within this environment, there is often minimal awareness of the services provided on campus, thus leading to an overwhelming feeling and fear of not having the support to succeed.

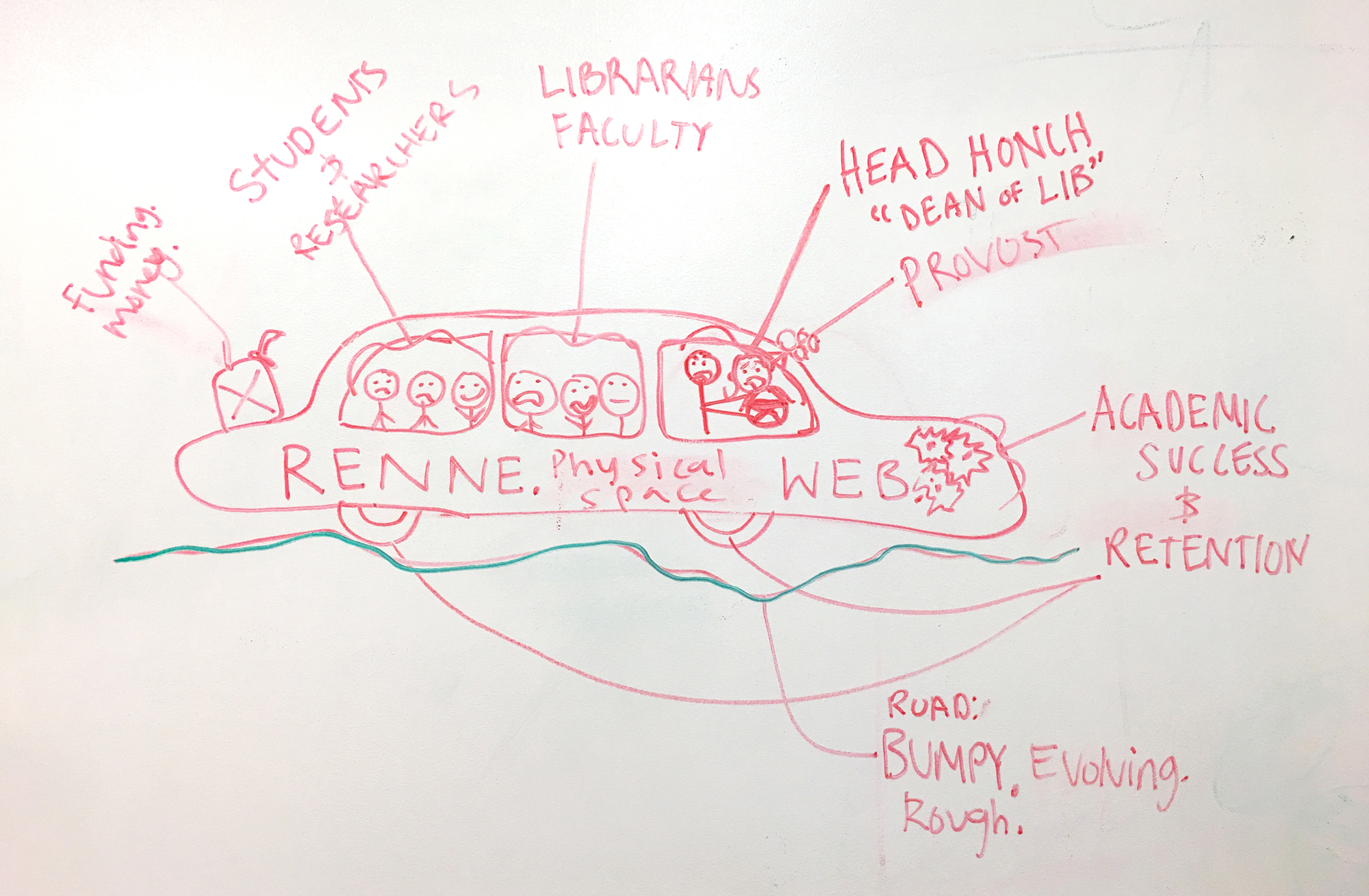

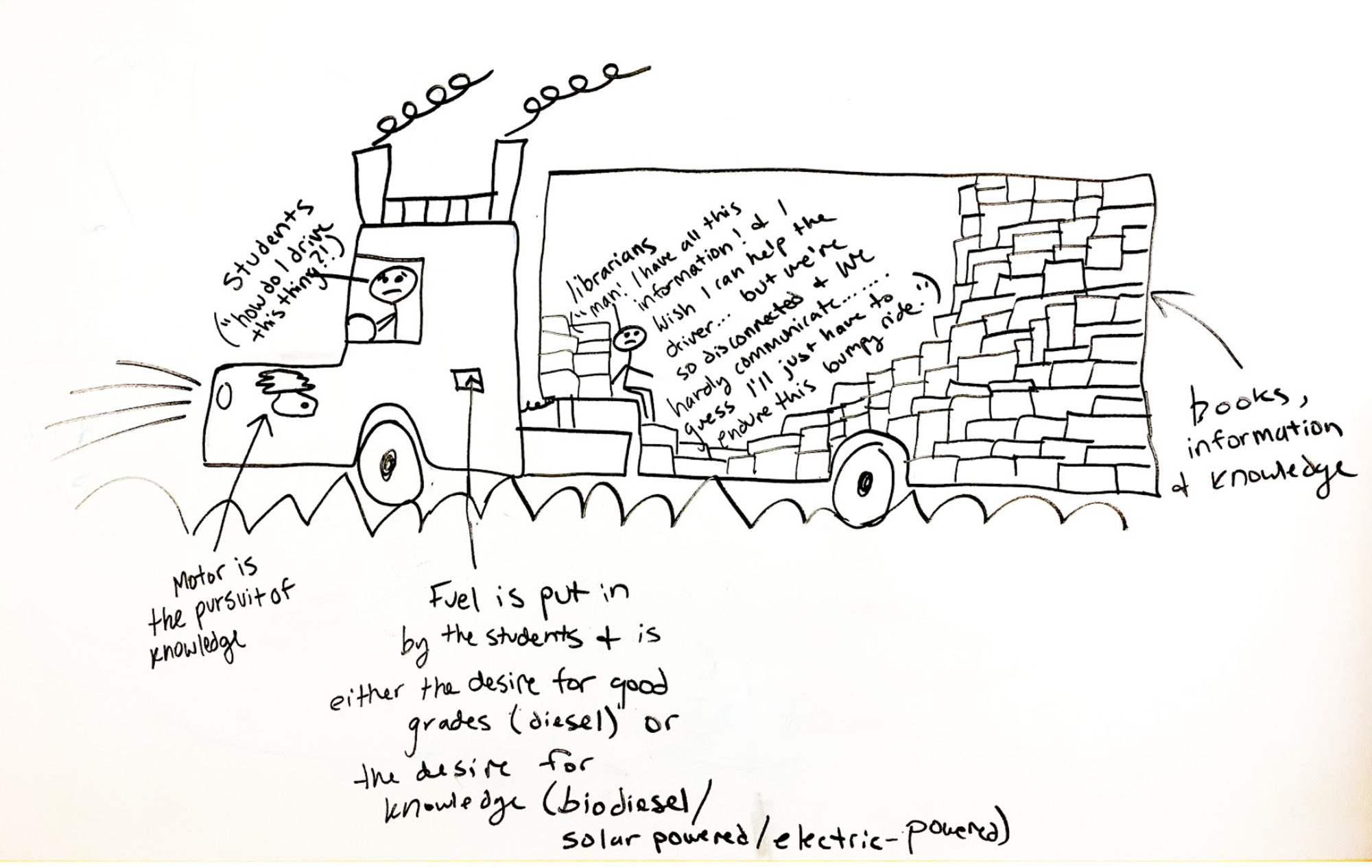

SY: Another key exercise was Build Your Vehicle (figs. 3 and 4). In this exercise, we each drew a car that represented our understanding of the library, with the component parts of the library mapped to the component parts of the car. In this metaphorical construction, we asked: What is the steering wheel? Who is driving? What does the road look like?

Figure 3. The Build Your Vehicle exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing the difficulty that students encounter when navigating the library’s digital and physical spaces.

Figure 3. The Build Your Vehicle exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing the difficulty that students encounter when navigating the library’s digital and physical spaces. Figure 4. The Build Your Vehicle exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing the disconnect between students and librarians.

Figure 4. The Build Your Vehicle exercise completed by one UXUP participant, showing the disconnect between students and librarians.CB: Build Your Vehicle showed the frustrations and barriers we encountered as students. By observing everyone’s drawings of vehicles we noticed that there was one commonality—everyone had a bumpy road! We each had our own vehicles, but we’re on the same road.

SY: This started to shape the idea that we wanted to further investigate the bumpy road as a main issue.

CB: These early exercises surfaced problems and issues we had with using the library and being on a bumpy road: that the campus environment could be overwhelming and that the library space and services could be intimidating. During Stage 1, we acknowledged each other's views and perspectives, which led to us learning more about each other and the library.

SY: And for me, I learned more about the backgrounds and life experiences of the student group, and which aspects of the library the students cared about, and which helpful services were invisible. In sum, the Stage 1 exercises allowed us to build comfort and confidence in each other and the design process early on, and to build trust and find connections points in each other. The interviews, the Time Machine, and Build Your vehicle all provided us with the conversational space to build empathy, understanding, and insight. The exercises helped raise important questions about students experiences on campus, and where the library fits into or didn’t fit into the lives of the participants. Through these exercises we began to see the role of the library in relation to the needs and priorities of the participants. With the bumpy road as our key insight and main problem, our next step was then to create ideas for how to respond to this main problem. Do we build a special web app? Modify our physical space? Develop a new outreach approach? These questions set up Stage 2, where we worked to generate ideas for responding to key issues surfaced in Stage 1.

Stage 2: Idea Generation

CB: The exercises within Stage 2 were used to generate ideas for solving the main issue of the bumpy road. These exercises included: Predict Next Year’s Headlines, Collage, Journey Map, Value Curve, and Clockwise.

SY: Stage 2 was designed to focus our direction, as informed by the evidence produced through the Stage 1 exercises. At the end of this design process, how will we have smoothed out the bumpy road? As a metaphor for the experience of the library, the road was effected by any number of factors that surfaced in Stage 1: university as overwhelming; library as intimidating: space, people, stuff, know-how; keeping connections to home; building friend networks; library building aesthetics; website usability; students’ lack of knowledge about relevant library services. Celina and I met to discuss the exercises that would be most suitable for addressing these challenges. Predict Next Year’s Headlines, for example, asks participants to think into the future and imagine the best possible outcomes for the project, so Celina and I agreed that this exercise is perfect for providing direction and momentum towards our end goal. The other exercises were similarly selected due to their potential for generating evidence that could help identify possible solutions to our main problem of the bumpy road.

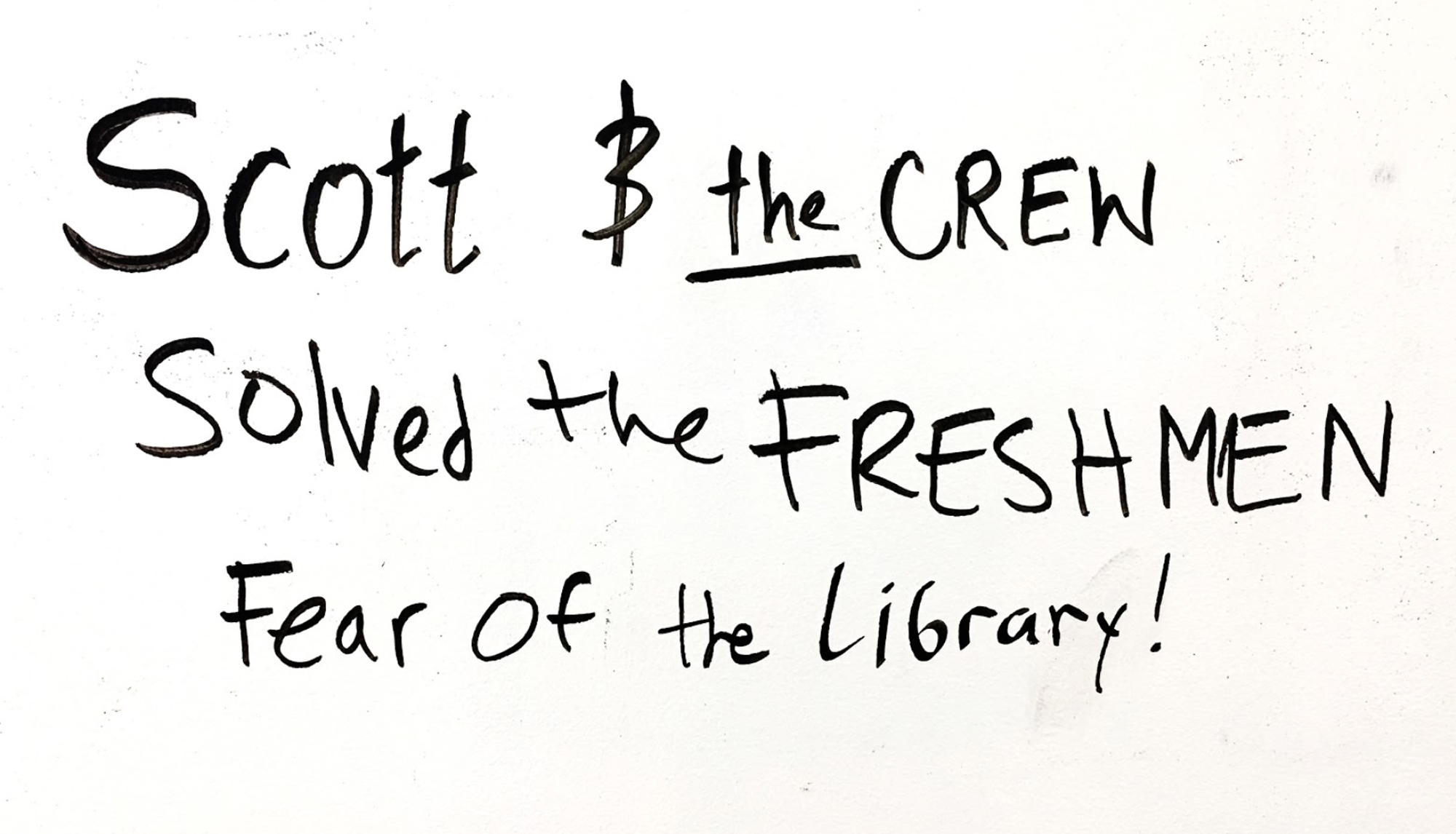

CB: To help focus our design inquiry, we initially began with Predict Next Year’s Headlines, where we imagined a newspaper was reporting on the outcomes of our project—what will the headline be announcing? (fig. 5). This was a critical exercise that helped create the base of the outcome of our project. We were then able to clarify our priorities for the project. This exercise led to a reflective dialogue about what we want our library to be, and what we wanted this project to accomplish.

Figure 5. The Predict Next Year’s Headlines exercises completed by one UXUP participant, showing the desired outcome of the project.

Figure 5. The Predict Next Year’s Headlines exercises completed by one UXUP participant, showing the desired outcome of the project. SY: To then open this inquiry up with a more visual approach, we constructed collages that responded to the following prompt: “How do you want the library to make you feel?” The goal with this exercise was to highlight emotional responses to the idea of the library.

CB: In one example (fig. 6), we see that the library should create an environment where one is happy, inspired, confident, and comfortable. Where one would feel part of a community, and is building strong relationships while on a journey working towards a goal.

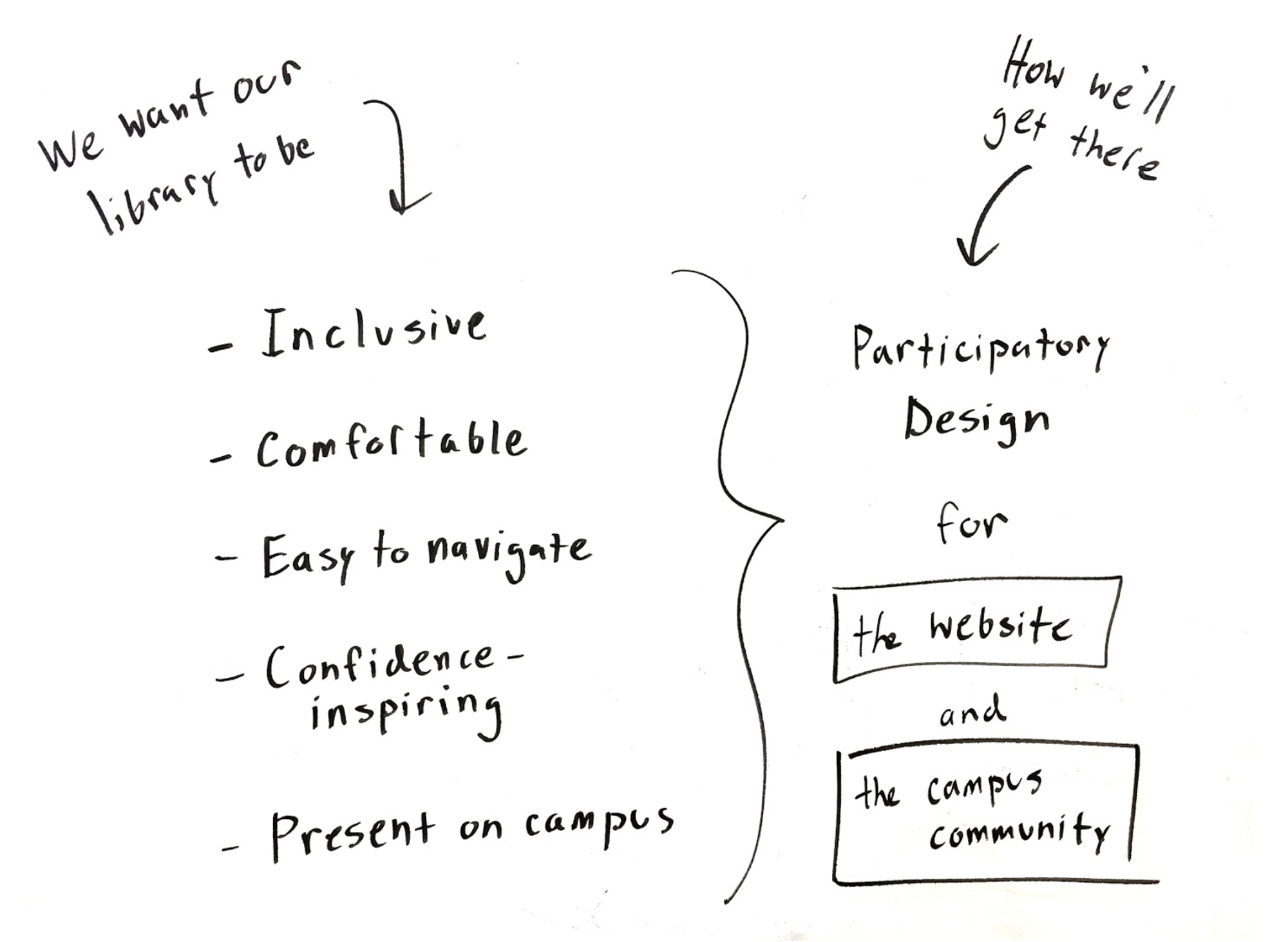

SY: Following the headlines and the collages, we set time aside in our meetings to reflect on, talk through, and analyze our progress so far. We decided as a group that we wanted a library that was inclusive, comfortable, easy to navigate, confidence-inspiring, and present on campus (fig. 7).

Figure 7. Design notes that reflect a shared vision of the UXUP participants. During the design process, it was important to dedicate time to reflect on the design process, analyze and interpret the evidence together, and collaboratively determine next steps.

Figure 7. Design notes that reflect a shared vision of the UXUP participants. During the design process, it was important to dedicate time to reflect on the design process, analyze and interpret the evidence together, and collaboratively determine next steps.CB: By having this conversation, two main design outcomes emerged as feasible and desirable for addressing the issues we were seeing—web usability or community outreach.

SY: In my daily work, I focus on the library’s website and have a bias towards technology solutions, so I thought that the website could be an impact area for the students.

CB: But the students thought, “Why would we use the library website if we didn’t know what services the library provided?” This led us to think beyond the website and to more basic needs and priorities of students that could be addressed with a community-building outreach tool.

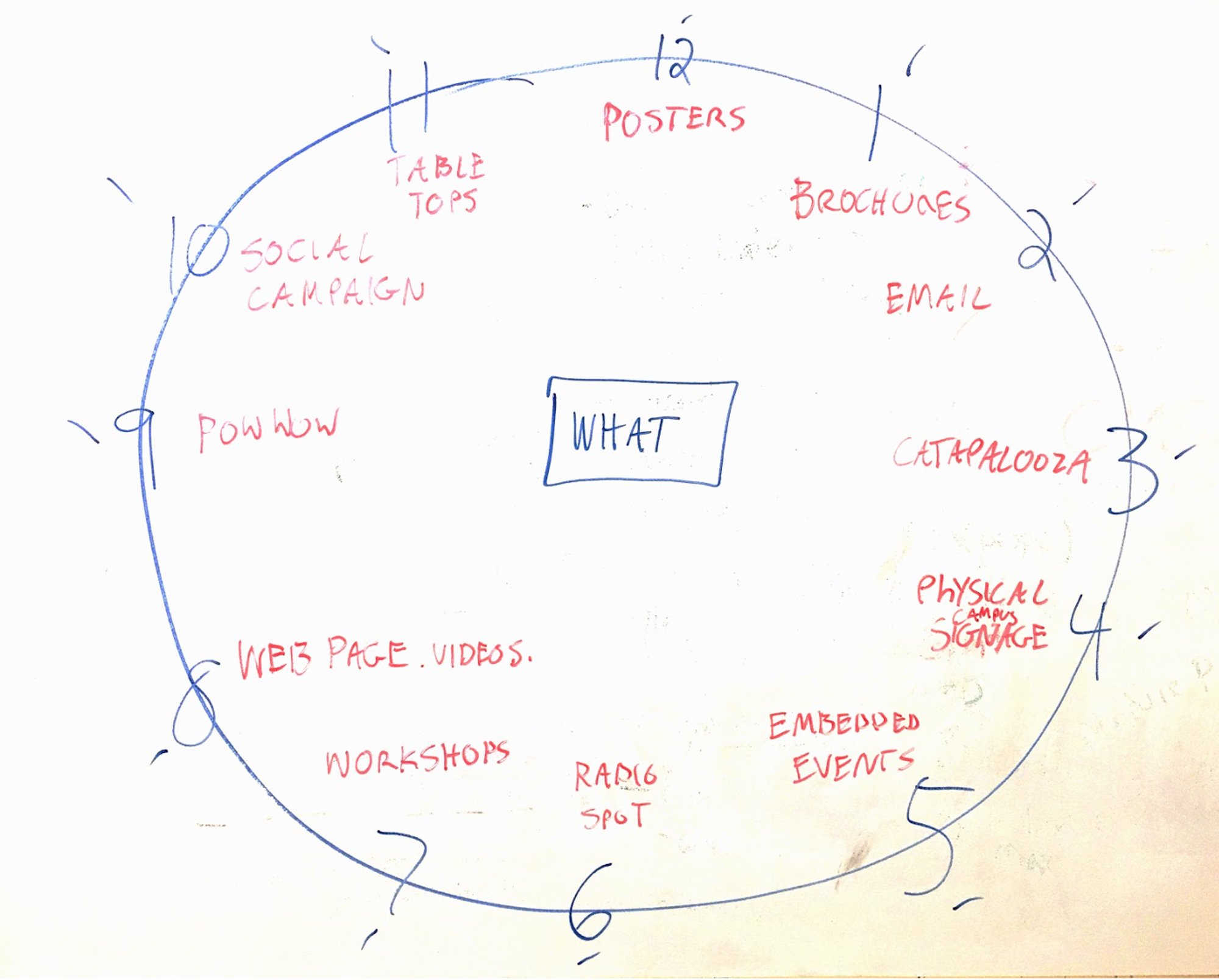

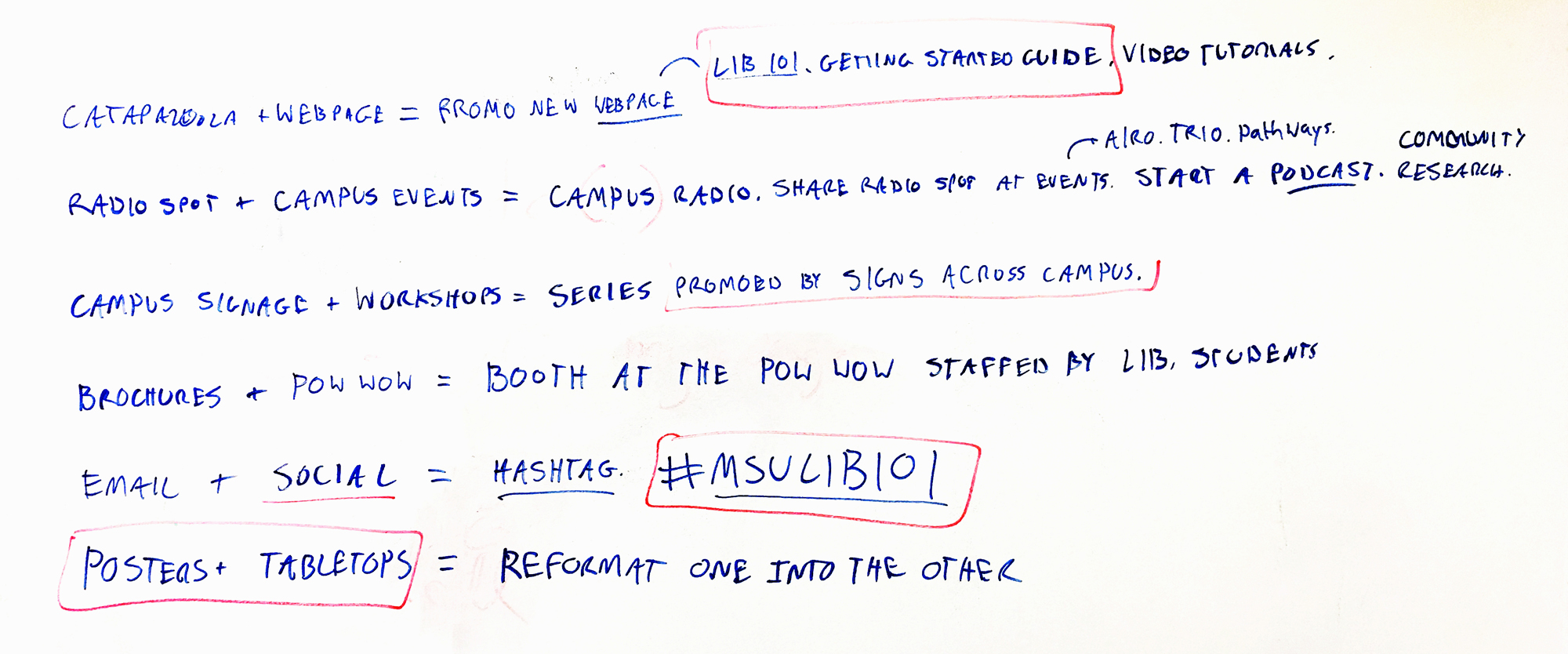

SY: To help us generate ideas for community outreach, we then played the game Clockwise (figs. 8 and 9). Combine different ideas to create a new better idea. Goal: create ideas for responding to the main problem.

Figure 8. Part 1 of the Clockwise exercise completed by the UXUP group, showing a variety of possible approaches for community outreach and engagement.

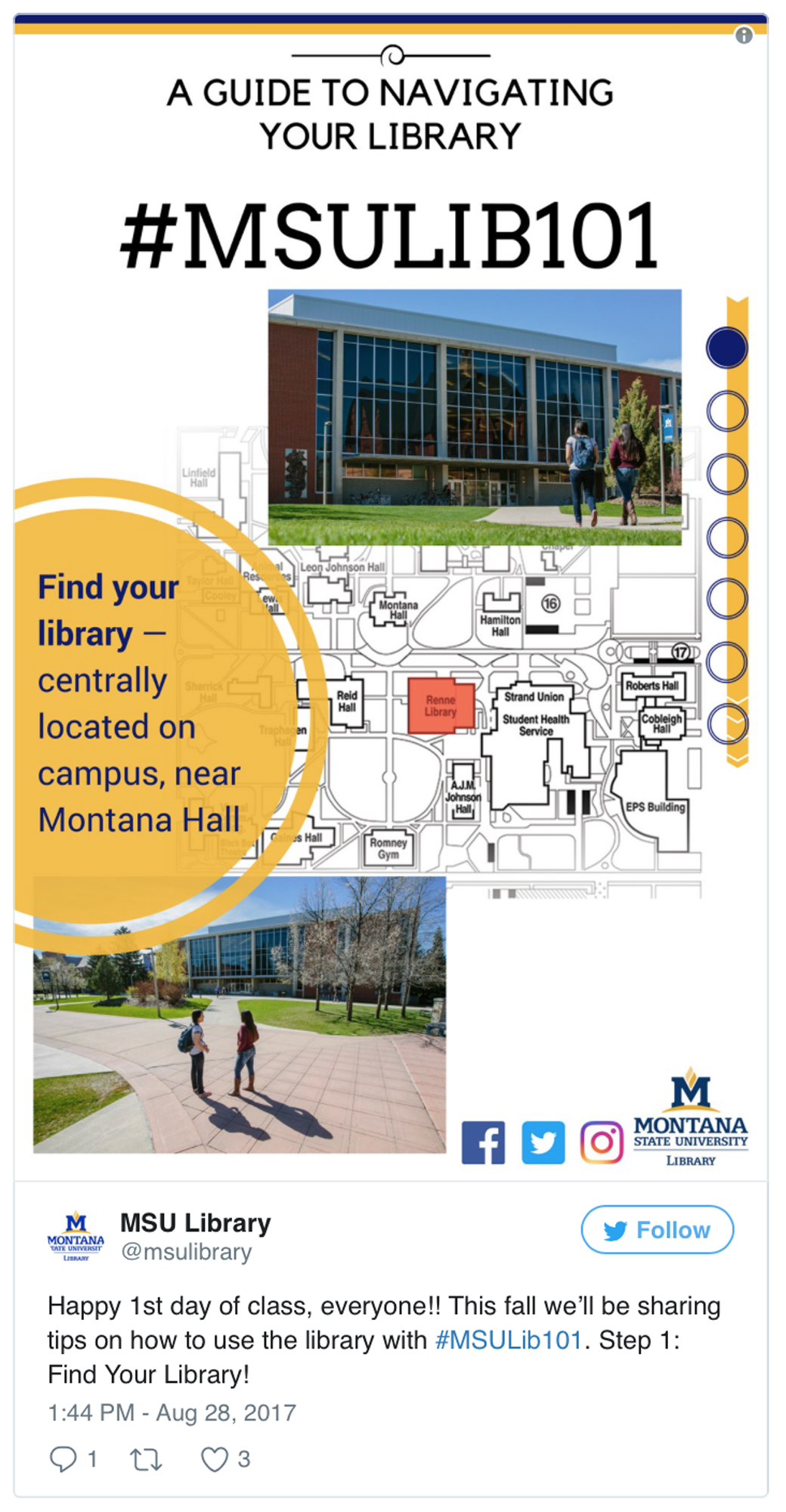

Figure 8. Part 1 of the Clockwise exercise completed by the UXUP group, showing a variety of possible approaches for community outreach and engagement. Figure 9. Part 2 of the Clockwise exercise completed by the UXUP group, showing a variety of possible approaches for community outreach and engagement mixed together. The group discussed which of these approaches were the most promising. Those approaches were then marked in red: a getting started guide called #MSULib101, promoted across campus with posters.

Figure 9. Part 2 of the Clockwise exercise completed by the UXUP group, showing a variety of possible approaches for community outreach and engagement mixed together. The group discussed which of these approaches were the most promising. Those approaches were then marked in red: a getting started guide called #MSULib101, promoted across campus with posters.CB: We pulled out the most desirable, feasible, and viable options, and synthesized them into a single idea: a “getting started” poster series called #MSULib101 that targeted first-time library users with key library activities.

SY: The decision-making process that led to this idea took the form of a facilitated dialogue during one of our design workshops. After completing the Clockwise exercise, I led the group through an analysis of the evidence produced. The students identified the components that they thought would be most effective for reaching the Native population on campus and addressing the key problem of the bumpy road identified during Stage 1. These components are marked by a red box in the figures: LIB101 Getting Started Guide, Signs Across Campus, #MSULIB 101, Posters + Tabletops. The “getting started” poster series was initially suggested by a student participant as a way to synthesize these ideas into a single design product. All participants agreed that an idea of a poster series was the best next step, based on a criteria of desirability, feasibility, and viability that I had introduced to the group. We discussed together each factor. For desirability we asked, “Do students want this?” For feasibility, we asked, “Can we make this?” For viability we asked, “Will this work?” For each question, the answer was yes for each member of the group.

CB: With the idea of a poster series in place, we entered Stage 3, where we evaluated this idea further, and worked towards implementation.

Stage 3: Evaluation and Implementation

SY: Stage 3 exercises allowed us to bring more depth and detail to the final product. Through more games, discussion, and voting, seven key activities for first-year students were identified as important: finding the library, tutoring, writing center, research help, group study rooms, coffee and downtime, and checking out technology.

CB: We sequenced these seven activities into a narrative of library usage so that the posters worked as a group to tell a cohesive story, and also individually to highlight certain activities. The number seven was also has cultural meaning to us students, as members of northern plains tribes.

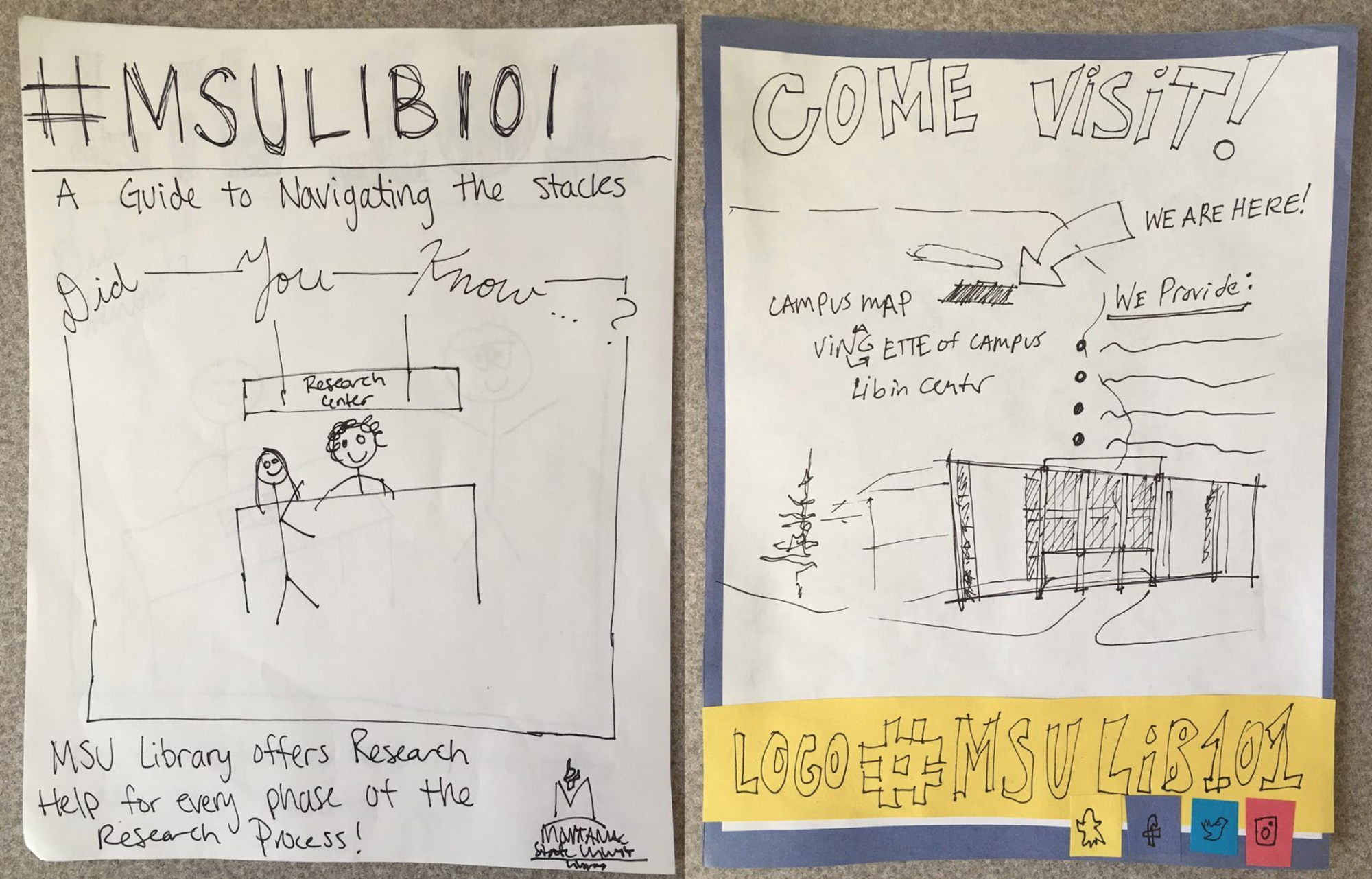

SY: To bring the final poster design more into view, we experimented with content, layouts, and presentation using paper prototyping (fig. 10).

Figure 10. The Paper Prototyping exercise completed by two UXUP participants, showing working drafts for the promotional poster series.

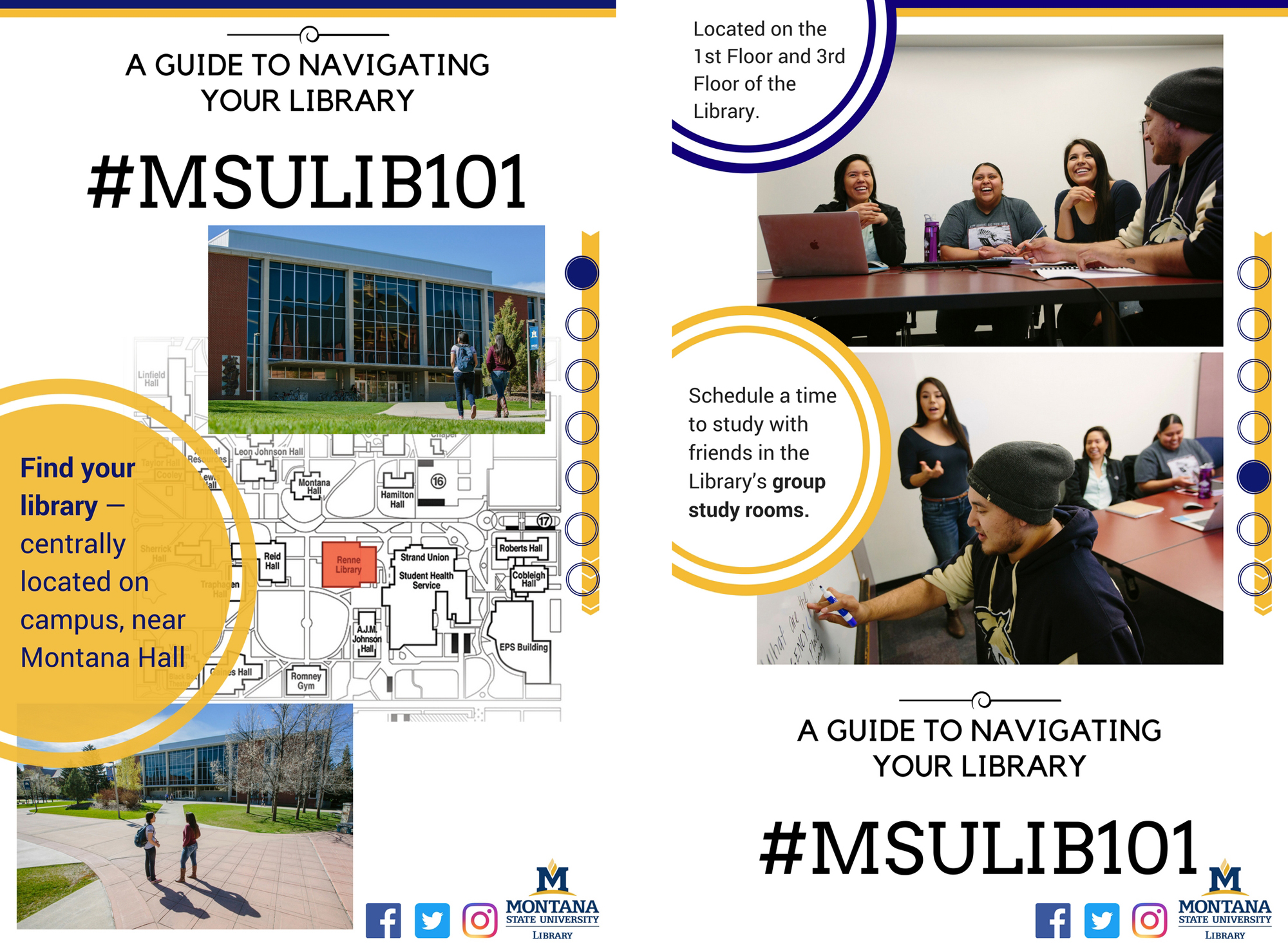

Figure 10. The Paper Prototyping exercise completed by two UXUP participants, showing working drafts for the promotional poster series.CB: For the final design (fig. 11), we wanted a simple, informative poster that can be read in a glance. We used the design exercise Club Members to determine the design requirements of the posters. To complete Club Members, participants create thematic categories—or “clubs”—in order to synthesize ideas. So, we worked together to identify the colors, content, social media icons, layouts, and photographic representations for our posters. Importantly, the members of the design group were represented in the posters. We also discussed where on campus these posters should appear, with a focus on important gathering places for Native students, such as our university’s American Indian Center. With the design requirements in place and discussed as a group, I used the graphic design software Canva to create the final designs.

SY: We also discussed and decided where the posters should appear in physical and online spaces, such as digital signage, social media (fig. 12), tabling events, our campus’ American Indian Center (fig. 13), and in residence halls.

Figure 12. A Twitter post from Montana State University Library, showing the #MSULib101 social media campaign connected to the UXUP poster series.

Figure 12. A Twitter post from Montana State University Library, showing the #MSULib101 social media campaign connected to the UXUP poster series.CB: The promotion of the poster series was coordinated with the fall semester. At the time of this writing, the posters are in spaces all across campus.

Outcomes and Reflections

SY: In reflecting back on the process, we note a number of outcomes and insights that resulted from UXUP. In terms of power and participation, we intentionally worked as a group to share power so that we could create a space for us all to participate and contribute towards the final design product. For me as the librarian participant, this meant that I stepped back from my position of authority and allowed the Indigenous student voice to come forward to be understood, respected, and influential in the design process. Celina and I talked through each stage of the process together with the UXUP group, and decided as a group how to proceed and what to create.

CB: You can follow any type of design exercise, but the approach needs to have a supportive, open, and encouraging environment, where there is space for new perspectives and where the participants feel empowered. Within a design context, space can be interpreted as a physical space, conversational space, and a mental space. These spaces converged in a way that was conducive to creative, open design work.

SY: The designer can maintain power in the design process by imposing more structured methods onto participants (Ryen, 2000). In following an open-ended, participatory approach that responded to participants’ needs and priorities, UXUP gave power to the students to shape the final design product. Such an approach can cultivate decolonized spaces where Indigenous voices can be heard and heeded. Through the exercises, the students were empowered as storytellers of their own experiences. In describing their backgrounds, needs, and priorities, the students provided essential direction for the project.

CB: When using participatory design, it is critical to design with and not for. For the UXUP project, Scott participated in all the design exercises with us. Through sincere collaboration and consensus-building, we were able to model a different way to make decisions within a the spaces of the library with Indigenous students.

SY: This represents the political outcome of participatory design, where democracy, empathy, and shared power help shape a more just world for all people, and especially for those who have been traditionally underrepresented. UXUP created a new conversational and creative space in the library where Indigenous participants took center stage as storytellers of their own experiences. The views of the student participants were essential for determining the direction of the process and ultimately the final product. While UXUP was a small project, it can provide a model and a point of reference for others who wish to replicate or expand this work.

CB: For the student participants, UXUP generated a new sense of community and belonging. As we reflected within the UXUP group, you don’t just walk into someone’s house without being invited. This project served as an invitation for us and other Indigenous students to enter the space of the library, to be welcomed, and to use the services that will help us succeed in a complex academic environment.

SY: In terms of practical outcomes, the project led to the creation of the promotional poster series. It also led to greater levels of expertise for all participants. For me, I have become a more empathetic librarian who can better serve the Native community on campus. Over the six-month course of the project, I became much more culturally attuned to the nuances of Indigenous cultures.

CB: Currently, the other students and I feel more comfortable and confident in the library. We are now aware and use the services that the library provides, such as the technology checkout, group study rooms, and working with librarians on research projects. Fundamentally, the UXUP project introduced us to the library, which in turn had a positive effect in our sense of belonging and academic success here at Montana State University. We now feel more at home on campus. And I and the other student participants became much more knowledgeable and confident about using the library.

SY: The next step for UXUP is to continue theorizing and practicing participation, decolonization, and indigenization. UXUP worked to build a microcosmic world that intentionally strove toward the political ideals of anti-oppression and social justice. Through further socially-active, politically-conscious, values-driven design in libraries, the broader world can become more inclusive, equitable, and just.

Recommendations for Practice

Next Steps for Practitioners

As a model for working co-creatively with diverse participants, UXUP can be adapted in other library contexts. In this section, we outline three key recommendations to help practitioners implement participatory design with underrepresented populations.

Self-Educate and Self-Reflect

For a non-Indigenous person, working with Indigenous peoples begins with self-education and self-reflection on the topics of racism, sexism, colonialism, and other intersecting systems of oppression that have benefited European settlers at the expense of Indigenous peoples of North America for centuries (Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014; Collins & Bilge, 2016). In her essay, “White People: I Don’t Want You To Understand Me Better, I Want You To Understand Yourselves,” critical race theorist Ijeoma Oluo (2017) directly and succinctly addresses this process by saying: “Heal thyself.” A process of healing and growth can come from a reading of critical race theory (Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller, & Thomas, 1996; Kivel, 2017) and critical pedagogy (Grande, 2015), especially from sources written by people of color. Follow-up discussions with other like-minded people will deepen understanding. A process of open, honest, and selfless education and reflection on these challenging topics forms the basis for a decolonizing Indigenous participatory design practice.

With a foundation of education and from a place of reflection, we can pose critical, rhetorical questions that shape and strengthen our research processes and practice areas:

- How can we improve the conditions of marginalized, underrepresented, and oppressed peoples?

- How can we engage with and deconstruct dominant stories and oppressive power structures?

- As researchers, how can we engage more critically with the research process?

- As practitioners, how can we bring Indigenous voices into our areas of practice?

The answers to these questions will depend on specific contexts. The Indigenous participatory design approach expressed through UXUP was informed and guided by these questions.

Tools, Techniques, and Structures

The practice of participatory design relies on a set of tools and the knowledge of their techniques. We can recommend a few resources that have proved invaluable for our practice:

- 75 Tools for Creative Thinking – This set of 75 design exercises provides the structure of co-creative design workshops.

- Gamestorming – This book provides an accessible introduction to workshops based on design games, with many detailed exercises that can be adapted for different purposes.

- Brand Deck – The Brand Deck provides a tool of expression for participants to verbally describe a situation or a problem.

- Intuiti Creative Cards – Similar to the Brand Deck, the Intuiti deck also provides a method of expression based on hand-illustrated visual designs.

Limitations of Participatory Design

While participatory design has great potential as a methodology for creating better user experiences and a more just world, there are real and significant challenges that limit the work.

Organizational Resources and Values

The ability to practice participatory design with underrepresented and marginalized populations depends in large part on the resources available to the practitioner and participants in the form of time and money. A given organization may not immediately value work that moves at a slower pace, or that has uncertain outcomes, or that isn’t motivated by political and social justice concerns. A given organization can be persuaded, however, to support such work. We hope that this paper and its references can help guide librarians in implementing participatory design initiatives at their organizations.

Achieving Genuine Participation

The nature of participation is a central and ongoing question of participatory design (Bowen et al., 2013; Vines, Clarke, Wright, McCarthy, & Oliver, 2013). This question is doubly important when working with Indigenous communities who may have a level of distrust developed from long histories of exploitation from Western researchers. Achieving genuine participation is therefore confronted with a variety of challenges: historical tensions, logistical hurdles, resources limitations, and entrenched power structures. Bratteteig & Wagner (2016b) encourage practitioners to maintain a critical awareness of themselves and their institutions vis-à-via the needs of participants. A designer’s own interests or their organization’s reward structures may conflict with the needs and priorities of participants. In such cases, designers should respect the decisions of participants, despite disagreements. Two guiding and fundamental questions for achieving participation in a participatory design project: “Whose questions are we asking? Who benefits from the answer?” Participants themselves should be at the center of project planning, the design process, and its outcomes.

Entrenched Power and the Limits of Decolonization and Indigenization

Indigenization calls for the researcher or practitioner to invoke and integrate Indigenous knowledge, epistemologies, methodologies, frameworks, and inquiries. Decolonization calls for a critical review of Western-constructed histories and organizational structures with a view towards deconstructing the systems of oppression that continue to harm marginalized communities. These processes, whether approached individually or in tandem, rely on those in power giving up their positions of privilege. Decolonization and indigenization require resources and power to flow in new directions.

For the UXUP project, we modeled a different approach for making decisions and sharing power within the library. But our insights may not in fact lead to sustained inclusion and increased equity for the participants or for our local Native American community. Though we aspired to indigenization through participatory design, such a goal may not be fully achievable with a design process shaped by a non-Indigenous, Scandinavian paradigm. Moreover, some have argued that decolonization and indigenization of libraries and museums is in fact unachievable, given that Western institutions and individuals are so embedded in the history and power structures of colonial oppression (Kassim, 2017). Indigenous Studies scholar Andrea Landry (Anishinaabe) asserts, “The process of decolonizing and indigenizing colonial systems does not, and cannot, work. And they do not, and cannot, work because any process that has to do with decolonization and indigenization within colonial systems must ultimately follow colonial rules and behave fundamentally colonial. Meaning all outcomes will still be primarily, colonial.” (Landry, 2018). Within this broader context of Indigenous justice and the long history of colonization, non-Native librarians must walk a highly fraught and politically-charged path toward Indigenous equity and inclusion in our organizations and in our profession. Many of our libraries reinforce Western values and viewpoints at the expense of Indigenous languages, cultures, and protocols, which produce significant barriers to Indigenous participation (Andrews, 2018).

With the knowledge of these challenges, participatory design offers one approach for participation and power sharing with Indigenous peoples. To deepen this approach in response to Landry and Andrews, the participatory design practitioner should expand their critical understanding and practice around decolonization and indigenization, with greater and more meaningful power sharing and participation with Indigenous peoples through a thoughtful integration of Indigenous research methodologies and participatory design. Decolonization and indigenization may not be fully achievable, but striving towards these goals with the aspiration of a more just library can strengthen our organizations and benefit those we serve.

Conclusion

Participatory design is based on the principle that people have a right to influence their own world. This socially-active, politically-conscious, values-driven approach to co-creation can bring about better services and experiences for users through a process of empowerment and mutual learning. With its focus on shared power and co-creative participation, the tradition of participatory design finds common ground with decolonizing and indigenizing approaches that seek to address historical imbalances of power and participation. In bringing these practices and concepts together, the UXUP project presents a model for building inclusive spaces where Indigenous voices can be heard and heeded in the design of a library. Through a critical practice of participatory design, we can build a library that not only listens to and responds to Indigenous students, but one that deserves to serve Indigenous students.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank their fellow participants on the UXUP project. Special thanks to Mary Anne Hansen and Richard White for their support and guidance throughout the project. We also recognize and appreciate the valuable feedback of the anonymous peer reviewers as well as the editors at Weave. Finally, we are indebted and grateful to all justice-oriented librarians, participatory designers, and Indigenous researchers whose work served to inform and inspire UXUP.

References

- Andrews, N. (2018). Reflections on resistance, decolonization, and the historical trauma of libraries and academia. In K. P. Nicholson & M. Seale (Eds.), The politics of theory and the practice of critical librarianship. Library Juice Press. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MVA35

- Baildon, M., Hamlin, D., Jankowski, C., Kauffman, R., Lanigan, J., Miller, M., ... Willer, A. M. (2017). Creating a social justice mindset: Diversity, inclusion, and social justice in the Collections Directorate of the MIT Libraries (Report). Retrieved from http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/108771

- Bannon, L. J., & Ehn, P. (2013). Design: Design matters in participatory design. In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 37–63). New York: Routledge.

- Banks, S., Armstrong, A., Carter, K., Graham, H., Hayward, P., Henry, A., Holland, T., Holmes, C., Lee, A., McNulty, A., Moore, N., Nayling, N., Stokoe, A., Strachan, A. (2013). Everyday ethics in community-based participatory research. Contemporary Social Science, 8(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2013.769618

- Barratt, M. J., & Maddox, A. (2016). Active engagement with stigmatised communities through digital ethnography. Qualitative Research, 16(6), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116648766

- Bech-Petersen, S., Mærkedahl, L., & Krogbæk, M. (2016). Participatory design and public galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAM) sector. In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Interactive Exhibitions, Workshops - Volume 2 (pp. 115–116). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2948076.2948095

- Billey, A., Drabinski, E., & Roberto, K. R. (2014). What’s gender got to do with it? A critique of RDA Rule 9.7. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.uvm.edu/libfacpub/19

- Bjerknes, G., & Bratteteig, T. (1987). Florence in wonderland: System development with nurses. In Computers and Democracy: A Scandinavian Challenge.

- Bjerknes, G., & Bratteteig, T. (1995). User participation and democracy: A Discussion of Scandinavian research on systems development. Scand. J. Inf. Syst., 7(1), 73–98.

- Bocci, M. C. (2016). (Re)framing service-learning with youth participatory action research: examining students’ critical agency (Text). The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Retrieved from https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/listing.aspx?id=19538

- Bossen, C., Dindler, C., & Iversen, O. S. (2016). Evaluation in participatory design: A literature survey (pp. 151–160). In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Full papers - Volume 1. New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2940299.2940303

- Bowen, S., McSeveny, K., Lockley, E., Wolstenholme, D., Cobb, M., & Dearden, A. (2013). How was it for you? Experiences of participatory design in the UK health service. CoDesign, 9(4), 230–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2013.846384

- Bødker, S., & Zander, P.-O. (2015). Participation in design between public sector and local communities. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Communities and Technologies (pp. 49–58). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2768545.2768546

- Brandt, E., Binder, T., & Sanders, E. B.-N. (2013). Tools and techniques: ways to engage telling, making, and acting. In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 145–181). New York: Routledge.

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2014a). Design decisions and the sharing of power in PD. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Industry Cases, Workshop Descriptions, Doctoral Consortium Papers, and Keynote Abstracts - Volume 2 (pp. 29–32). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2662155.2662192

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2014b). Disentangling participation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06163-4

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2016a). Unpacking the notion of participation in participatory design. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-016-9259-4

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2016b). What is a participatory design result? In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers - Volume 1 (pp. 141–150). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2940299.2940316

- Brook, F., Ellenwood, D., & Lazzaro, A. E. (2015). In pursuit of antiracist social justice: Denaturalizing whiteness in the academic library. Library Trends, 64(2), 246–284.

- Caswell, M. (2017). Teaching to dismantle white supremacy in archives. The Library Quarterly, 87(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1086/692299

- Chilisa B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Washington, DC: SAGE Publications.

- Choudry, A. (2013). Activist research practice: Exploring research and knowledge production for social action. Socialist Studies/Études Socialistes, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.18740/S4G01K

- Collins, K., Cook, M. R., & Choukeir, J. (2017). Designing on the spikes of injustice: Representation and co-design. In D. Sangiorgi (Ed.), Designing for service: Key issues and new directions (pp. 106–116). New York: Bloomsbury.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Costantino, T., LeMay, S., Vizard, L., Moore, H., Renton, D., Gornall, S., & Strang, I. (2014). Participatory design of public library e-services. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Industry Cases, Workshop Descriptions, Doctoral Consortium Papers, and Keynote Abstracts - Volume 2 (pp. 133–136). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2662155.2662232

- Council on Library and Information Resources. (2012). Participatory design in academic libraries: Methods, findings, and implementations (No. 155). Washington, DC.

- Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Thomas, K. (Eds.). (1996). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New York: The New Press.

- Design Justice Network. (2017). 10 Ways Designers can Support Social Justice. In Design Justice Issue 3: Design Justice in Action (pp. 5–12). Oddities Prints.

- Dietrich, T., Trischler, J., Schuster, L., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2017). Co-designing services with vulnerable consumers. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(3), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-02-2016-0036

- Drabinski, E. (2013). Queering the catalog: Queer theory and the politics of correction. The Library Quarterly, 83(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1086/669547

- Drake, J. M. (2017). The urgency and agency of #OccupyNassau: Actively archiving anti-racism at Princeton. In S. W. H. Young & D. Rossmann (Eds.), Using social media to build library communities: A LITA guide (pp. 123–135). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dudley, M. Q. (2017). A library matter of genocide: The Library of Congress and the historiography of the Native American Holocaust. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2).

- Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Edmunds, D. S., Shelby, R., James, A., Steele, L., Baker, M., Perez, Y. V., & TallBear, K. (2013). Tribal housing, codesign, and cultural sovereignty. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 38(6), 801–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913490812

- Ehn, P. (1993). Scandinavian design: On participation and skill. In Participatory design: Principles and practice (pp. 41–77). CRC / Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Eubanks, V. (2009). Double-bound: Putting the power back into participatory research. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 30(1), 107–137. https://doi.org/10.1353/fro.0.0023

- Farnel, S., Shiri, A., Campbell, S., Cockney, C., Rathi, D., & Stobbs, R. (2017). A community-driven metadata framework for describing cultural resources: The Digital Library North Project. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 1–18.

- Frauenberger, C., Good, J., Fitzpatrick, G., & Iversen, O. S. (2015). In pursuit of rigour and accountability in participatory design. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74(Supplement C), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.004

- Giesbrecht, E. M., Miller, W. C., Mitchell, I. M., & Woodgate, R. L. (2014). Development of a wheelchair skills home program for older adults using a participatory action design approach. BioMed Research International, 2014, e172434. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/172434

- Grande, S. (2015). Red pedagogy: Native American social and political thought. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Harihareswara, S. (2015). User experience is a social justice issue. The Code4Lib Journal, (28). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/10482

- Hathcock, A. (2015). White librarianship in blackface: Diversity initiatives in LIS. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/lis-diversity/

- Hathcock, A. M. (2017). Cultivating critical dialogue on Twitter. In S. W. H. Young & D. Rossmann (Eds.), Using social media to build library communities: A LITA guide (pp. 137–150). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Holmlid, S. (2009). Participative; co-operative; emancipatory: From participatory design to service design (pp. 105–118). Presented at the DeThinking Service, ReThinking Design: First Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation, Oslo, Norway. Retrieved from http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp/article.asp?issue=059&volume=&article=009

- Hudson, D. J. (2017). On “diversity” as anti-racism in Library and Information Studies: A critique. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from http://libraryjuicepress.com/journals/index.php/jclis/article/view/6

- IDEO. (2015). The field guide to human-centered design. San Francisco: IDEO.

- Ippoliti, C., Nykolaiszyn, J., & German, J. L. (2017). What if the library... Engaging users to become partners in positive change and improve services in an academic library. Public Services Quarterly, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2016.1250694

- Iversen, O. S., & Dindler, C. (2014). Sustaining participatory design initiatives. CoDesign, 10(3–4), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.963124

- Iversen, O. S., Halskov, K., & Leong, T. W. (2012). Values-led participatory design. CoDesign, 8(2–3), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672575

- Johnson, A. (2015). Using participatory and service design to identify emerging needs and perceptions of library services among science and engineering researchers based at a satellite campus. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, (81). https://doi.org/10.5062/F4H99366

- Joseph, N. M., Crowe, K. M., & Mackey, J. (2017). Interrogating whiteness in college and university archival spaces at predominantly white institutions. In Topographies of Whiteness: Mapping Whiteness in Library and Information Science (pp. 55–78). Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

- Kapuire, G. K., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., & Blake, E. (2015). An insider perspective on community gains: A subjective account of a Namibian rural communities׳ perception of a long-term participatory design project. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74, 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.10.004

- Kassim, S. (2017, November 15). The museum will not be decolonised. Retrieved November 24, 2017, from https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/

- Kensing, F., & Blomberg, J. (1998). Participatory design: Issues and concerns. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 7(3–4), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008689307411

- Kensing, F., & Greenbaum, J. (2013). Heritage: Having a say. In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 21–36). New York: Routledge.

- Kia-Keating, M., Santacrose, D. E., Liu, S. R., & Adams, J. (2017). Using community-based participatory research and human-centered design to address violence-related health disparities among Latino/a youth. Family & Community Health, 40(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000145

- Kivel, P. (2017). Uprooting racism: How white people can work for racial justice. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers.

- Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Landry, A. (2018, January 11). Decolonization and indigenization will not create the change we need. Retrieved May 19, 2018, from https://indigenousmotherhood.wordpress.com/2018/01/11/decolonization-and-indigenization-will-not-create-the-change-we-need/

- MacTavish, T., Marceau, M.-O., Optis, M., Shaw, K., Stephenson, P., & Wild, P. (2012). A participatory process for the design of housing for a First Nations Community. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9253-6.

- Marquez, J. D., & Downey, A. (2015). Service design: An introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.201

- Marquez, J. J., & Downey, A. (2017). Getting started in service design: A how-to-do-it manual for librarians. Chicago: American Library Association.

- Moll, J. (2010). The patient as service co-creator. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference (pp. 163–166). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900466

- Morales, M., Knowles, E. C., & Bourge, C. (2014). Diversity, social justice, and the future of libraries. Portal: Libraries and the academy, 14(3), 439–451.

- Nygaard, K., & Bergo, O. T. (1975). The Trade Unions—New users of research. Personnel Review, 4(2), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb055278

- Oluo, I. (2017, February 7). White people: I want you to understand yourselves better. Retrieved October 29, 2017, from https://theestablishment.co/white-people-i-dont-want-you-to-understand-me-better-i-want-you-to-understand-yourselves-a6fbedd42ddf - .yz8genngk

- Robertson, T., & Simonsen, J. (2013). Participatory design: An introduction. In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 1–17). New York: Routledge.

- Rodil, K., & Winschiers-Theophilus, H. (2015). Indigenous storytelling in Namibia: Sketching concepts for digitization. In 2015 International Conference on Culture and Computing (Culture Computing) (pp. 80–86). https://doi.org/10.1109/Culture.and.Computing.2015.42

- Rolan, G. (2017). Agency in the archive: a model for participatory recordkeeping. Archival Science, 17(3), 195–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-016-9267-7

- Rowell, L. L., & Hong, E. (2017). Knowledge democracy and action research: Pathways for the twenty-first century. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research (pp. 63–83). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40523-4_5

- Ryen, A. (2000). Colonial methodology? Methodological challenges to cross-cultural projects collecting data by structured interviews. In C. Truman, D. Mertens, and B. Humphrey (Eds.), Race and inequality (pp. 220–233). London: UCL Press.

- Saunders, L. (2017). Connecting information literacy and social justice: Why and how. Communications in Information Literacy, 11(1), 55–75.