Start with an Hour a Week: Enhancing Usability at Wayne State University Libraries

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Instead of pursuing traditional testing methods, Discovery and Innovation at Wayne State University Libraries settled on an alternate path to user-centered design when redesigning our library website: running hour-long “guerrilla” usability tests each week for two semesters. The team found immediate successes with this simple, cost-effective method of usability testing, leading to similar redesign projects for other online resources. Emphasizing the importance of iterative design and continuous improvement, this article will detail the authors’ experience conducting short weekly tests, suggestions for institutions looking to begin similar testing programs, and low-stakes testing as a pathway to improved design for the library as a whole.

In spring 2016, the Discovery and Innovation web team at Wayne State University Libraries began a redesign of our main library homepage, making the first major updates to the site since 2013. After launching the initial design, we wanted to improve the new website with feedback from real users, following Jakob Nielsen’s decades-old assertion that redesigning websites based on user feedback “can substantially improve usability” (Nielsen, 1993). Instead of using remote and large-scale testing options, we chose a lean, iterative approach, and committed to two semesters of brief, weekly “guerrilla” usability sessions with student users. Not only did this method produce powerful results, but its attainable, iterative approach ultimately led to an increased user focus beyond the library homepage. If you have an hour a week, a laptop, and at least one other colleague willing to help, you can start usability testing, guerrilla-style.

Though we found success with this method, using such a stripped-down approach wasn’t immediately obvious. At the beginning of this project, we didn’t know a whole lot about conducting user testing, having relied mostly on survey responses, search logs, and Piwik website usage data to inform our initial redesign. Although we ran informal tests during the initial design process, participation was limited to library staff or student workers only. This feedback had been helpful early on, but we suspected that testing only employees may have skewed our findings. When compared to seasoned staff, many users would likely not be as familiar with library resources and website structure.

The web team considered a host of research methods before embracing lean usability. We considered running focus groups, but discovered our budget rules prohibited us offering even small gift cards as compensation, generally requisite for participation in such activities. As we explored focus groups further, we also realized that the amount of preparation needed to run a session would make it hard to get regular feedback on any changes we did end up making. Hiring an expert to run the kind of large-scale user test commonly outlined in literature or outsourcing testing to a website like UserTesting.com were other methods we eliminated. We wanted a way to test users that would allow us to spend less time planning and more time testing so we could get feedback and deliver usability improvements as fast as possible. The remainder of this piece will detail our experience conducting weekly tests, and suggestions for institutions looking to begin similar testing programs,.

Go Guerrilla

We first discovered the concept of lean usability via Jeff Gothelf’s 2013 book Lean UX: Applying Lean Principles to Improve User Experience. According to Gothelf, the concept of “lean UX” relies on two concepts. First, research should be continuous, meaning built into every step of the design process. Second, research should be collaborative, meaning done by the design team, not outsourced to specialists (p. 74). Further exploring research methods used by tech startups, we found “guerrilla” style testing, an incredibly lean, do-it-yourself process. (A similar method is also explored in Steve Krug’s 2010 testing bible Rocket Surgery Made Easy, though he never users the term “guerrilla”.)

Whatever you call it, this type of research aims to identify usability issues and fix them as quickly as possible. It can be successful with minimal planning, minimal staffing, minimal equipment, and minimal time. Just set up a table with devices for testing in a central location where your users are likely to be (instead of recruiting representative users ahead of time for off-site testing, guerrilla testers do it on the fly). Once you find a willing participant, you have them spend five to ten minutes completing a short series of scripted tasks while you observe and record the results. Then, you repeat the same test with four more participants, enough to reveal most of your site’s usability problems.

The results aren’t quantitative, but that’s okay. Informal observation like this is useful for design teams. When we began our guerrilla testing process, we decided to commit to an hour of testing every Thursday, and soon found it to be the most productive hour of our week. Krug puts it best: “It works because watching users makes you a better designer” (p. 17).

Start Testing

Identify User Needs

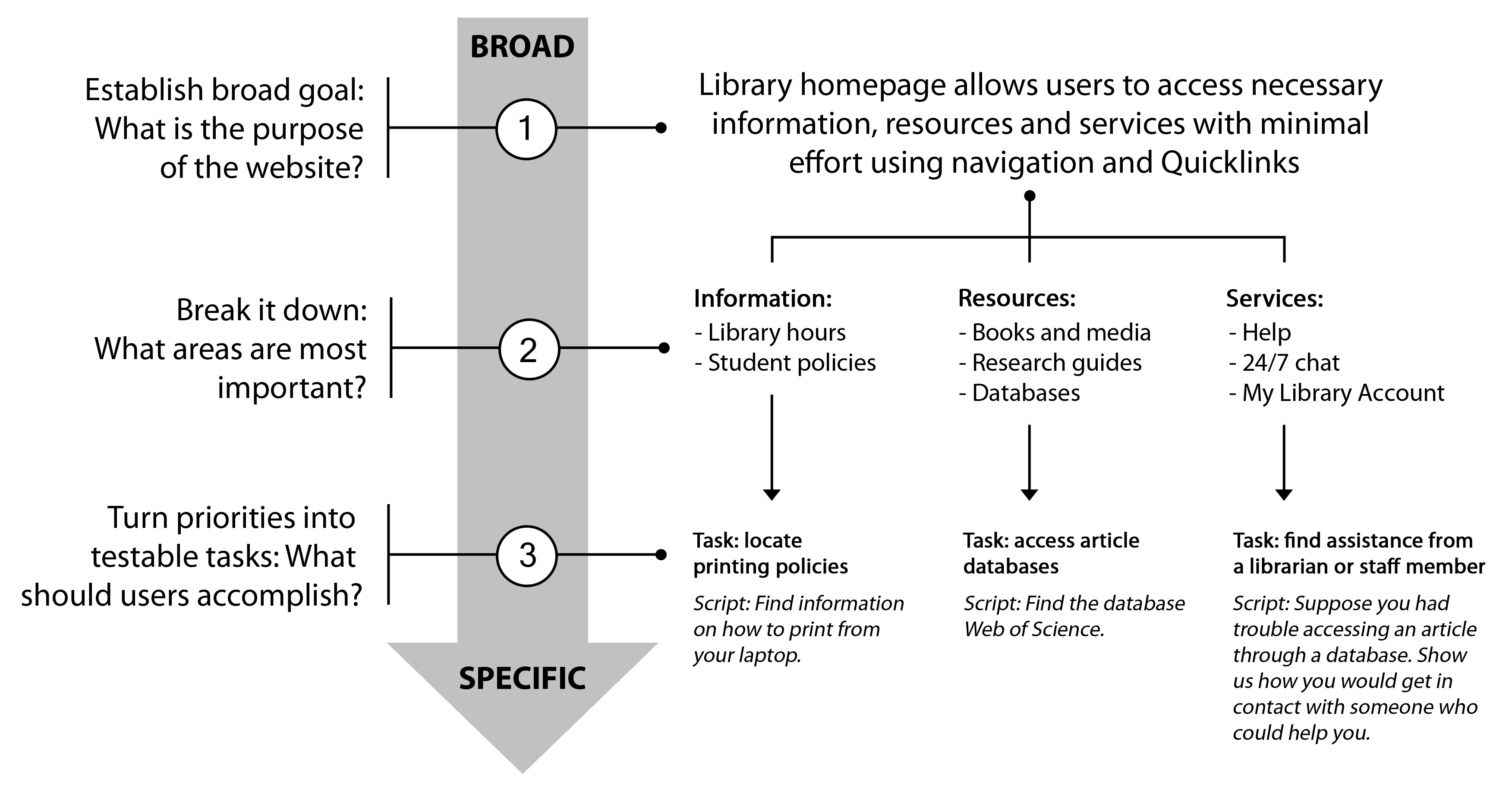

We identified broad goals, by first considering our user’s needs. What should they be able to accomplish? What type of experience should the interface offer? We dug into our usage data to find the most heavily-used portions of our site. This led to our initial goal to provide users intuitive access to information, resources, and services with minimal effort using both navigation and search. Then, we expanded our broad goal by exploring the details. Specifically, we wanted to support users in locating information about the libraries, like hours and student printing policies. We wanted them to be able to find and use resources like books, article databases, and research guides. We also wanted users to be able to find help if needed. These translated into measurable tasks for our initial tests, such as“ have user locate the database Web of Science,” or “have user contact a reference librarian.”

Though we first turned to our collected usage data to understand user needs, we also collaborated with other library staff members during the task creation process. By receiving input from circulation, reference, and liaison staff that regularly interacted with students, we were able to test user tasks may have been overlooked. Don’t worry about figuring everything out at once, and keep in mind that tasks are flexible. The more you test, the more tasks will change. We generally make an informal list of areas we want to test the week before, and consult it as we write the tasks.

Devise the Script

Once you’ve identified user tasks, it’s time to turn them into testable questions for your script. When constructing these questions, make sure to word them in a way that avoids leading the user to your desired action. Rather than asking our participants to locate the 24/7 chat service, we’ll propose a scenario instead. For example, “Suppose you had trouble accessing an article through a database. Show us how you would get in contact with someone who could help you.” Because we want it to take no more than five to ten minutes, we generally stick to six to eight questions per test.

We also prepare a handful of scripted answers in case participants tried to ask specific questions. This has been helpful because when we began testing, we often found ourselves thrown off by participant questions after following a script for so long. For instance, in response to a question about what an interface is supposed to do, we’ll reply, “What do you think?” or explain that we can answer any questions once testing is complete. If a participant seems stuck on a question, we will also give them the option to move on to the next one.

In our case, the person who runs the test is the same person who writes the script. However, collaboration and feedback are still essential during this stage. A day or two before our Thursday session, we review our questions as a team to double check content, phrasing, and tone. Once we approve the script, one of us will type the questions into a new Google Forms document, which we’ll use for note taking during the sessions. At this point, it’s also good to script an introduction that you’ll read to each user who participates in your session. We like to explain who we are, the project we’re working on, and the purpose of the test, so the user has an understanding of the end goal. You should also stress to the participant that there are no wrong answers: you are testing the site, not the skill of its users. It’s also important to encourage the participant to think out loud, and express any confusion or notable impressions. We keep this in our Google Forms document as well, so it’s easy to reference during the test and each participant hears the same introduction.

Run the Session

When it’s time to pick a location for the first test, choose a place you know your users will be, like near the entrance to your most visited library at a busy time. Discovery and Innovation finds willing participants by setting up a table with two laptops or devices—one for testing, one for recording results—near the entrance of our busy Undergraduate Library. We’ve tried other places on campus like the Student Center and the Purdy-Kresge graduate library, without as much success. The key for us was to find a place where there's a lot of traffic in and out of the library, during a time of day when students may be free. You want to make sure that it is a time and place that you can repeat regularly. We run our sessions as a group of three: one person recruits participants, one person runs the test, one person observes and records the results. Once we’re set up for the session, our recruiter approaches students with a friendly greeting, asking for five to ten minutes of their time to help test a new website we’re working on. If they seem interested, our moderator explains the test further, and with their permission, starts the session. We always offer a dish of fun-size candy as an incentive, but find that most volunteers are willing to help regardless. Our designated observer takes notes on participant behavior using Google Forms, where we have each script saved for easy access. When we’re done with the test, we make sure to thank users for their time, and remind them to help themselves to a piece of candy.

After a session, we have a quick web team debrief, where we review the results of the test, identify areas for improvement, and propose solutions for bugs or design issues our users uncovered. Over the next few days, we’ll make any necessary changes to the website that we’d like to test, reviewing them at our weekly web team meeting before our next testing session. If possible, don’t go live with untested improvements. We keep a separate test site for implementing changes so that we’re not changing the live site without running more tests. Once our edits are live on the test site, we restart the testing process to make sure our improvements are effective.

The concept of iteration has become the most important factor in our research and redesign. Regular testing lets us make small changes incrementally instead of huge redesigns, eliminating the risk of disorienting website users with abrupt, unexpected changes. One early success concerned the library’s 24-hour chat reference, branded as “Ask A Librarian” and consistently cited by staff members as an important service. Though this service was accessible from the site’s main navigation and a secondary “Ask A Librarian” page, initial tests revealed that many students were unaware of its existence, and also had difficulty finding it with the existing navigation. If students were able to locate it, they weren’t sure how to use it once they were there. After testing several iterations of our navigation, chat interface, and the “Ask A Librarian” page, we identified what worked. Within a month of implementing the final changes, we got word from our reference coordinator that use of the chat service was up by 70 percent. This was an early, measurable achievement that pushed us to continue with our testing plan.

The most major improvement we’ve made since redesigning the homepage involved our Millennium-based library catalog, which had gone untouched since 2006. In the spring of 2017 we began running user tests, revealing several issues with the design we’d had for over a decade, long before any of the current web team members were hired. In addition to upgrading our integrated library system to Sierra, we redesigned the catalog to modernize the look, added user-friendly features like citation and map tools, and tweaked language to be more intuitive for users. These changes wouldn’t have been easy to approach as a single redesign project. The small, iterative changes added up over time.

What makes this type of research easy to repeat is its informal approach. Krug (2010) explains, provided that you’re still getting the answers you need, there’s no problem in testing fewer users, altering tasks, or even skipping a task if a participant is struggling and it’s obvious why. The beauty of guerrilla usability testing is that it’s flexible; the most important thing is that you do it, early and often. Some of the improvements we were able to make revealed further weaknesses within our current workflows. Which brings us to our final point—this commitment to usability, starting with a mere hour of informal testing per week, has had an important effect on our journey toward a library-wide culture of usability.

References

- Gothelf, J. (2013) Lean UX: Applying lean principles to improve user experience. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly.

- Nielsen, J. (1993). Iterative user interface design. IEEE Computer, 26(11), 32–41.

- Krug, S. (2010). Rocket surgery made easy: The do-it-yourself guide to finding and fixing usability problems. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.