User Personas as a Shared Lens for Library UX

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

This paper was refereed by Weave's peer reviewers.

Introduction

Libraries interested in user-centered design are faced with a number of options for measuring and improving their library user experience—usability tests, contextual interviews, and direct observation being a few popular user research methods. While experts often encourage the use of multiple techniques for a fuller understanding of users and their needs (Pruitt & Grudin, 2003; Rohrer, 2014), this can be difficult for libraries with fewer resources or time for dedicated user research, making it important to consider practical tools to assess library UX and spur user-centered thinking.

User personas are one such tool, helping both communicate UX findings and knowledge of users, and helping guide the design process by ensuring that the right questions are being asked and users remain the central focus in decision making. The power of personas lies in their ability to distill knowledge of a target user group into relatable characters that are easy to remember and empathize with (Harley, 2015). This can help address a common problem among product design teams known as the “elastic user,” where a team’s definition of users will shift at different stages of the design process, and will often be different for each team member, reflecting their own personal biases and preferences (Cooper, 1999). By creating a concrete and shared definition of target product users, personas are a first step in creating a common, consistent vocabulary for user-centered design, helping facilitate discussions and encouraging a shared vision for product UX.

At Utah State University Libraries, personas provide an imperfect, but compelling lens for understanding library users, helping us assess and improve granular details of design like copy and layout, while also serving as a reminder to keep users at the center of the design process from start to finish. In the past, decisions and priorities for website development were primarily influenced by internal needs and preferences. Discussions of users were not central to the design process, and largely revolved around anecdotes and assumptions about library users, with little agreement on how to valuate or prioritize their assumed characteristics. Personas have helped address these problems by providing librarians, designers, and development staff with a common understanding of library users that is both concrete and evidence-based. For example, instead of starting with a list of features or goals as dictated by internal stakeholders, personas force us to consider the users’ expectations, needs, and goals to determine design features and specifications. As a project progresses, usability testing can help validate and refine our design, but returning to well-made personas also provides a practical way to keep our process on track and ensure our design is still reflecting users’ goals.

Like many libraries, we have sought out budget-friendly ways to incorporate UX into our everyday library practices. For example, we employ a lightweight usability model that allows us to quickly gather feedback without formal test procedures, and recently adopted a continuous design model that allows us to quickly respond to problems and make improvements as we learn more about our users’ needs. As a complement to this agile, budget-friendly approach, this article will propose a similarly lightweight method of persona creation that allows personas to be developed quickly and improved iteratively as they are put into practice.

What are Personas?

Personas are profiles of imaginary people that describe the behaviors, motivations, frustrations, and end goals of target users for a product or service. First proposed by Alan Cooper as a way to focus the design process (1999), personas typically include a portrait, background information, and other fictional details to help make the persona feel like a real person. As a stand-in for large groups of potential users, personas help to illustrate common behaviors and tasks that are shared among otherwise diverse groups of people, helping designers imagine how users might interact with a product and what features they need most to achieve their goals (Goodwin, 2008).

In concept, personas are similar to a list of product requirements that would traditionally be gathered from internal discussions or surveys of users. However, instead of listing out all potential features, personas focus the design process on only those features that support users’ tasks and end goals, helping to filter out non-critical items and exclude internal assumptions and preferences (Fox, 2014). As a UX tool, personas provide a memorable way to distill and synthesize user research, using fictional characters to describe findings in a more relatable, human way. Compared to an abstract list of design requirements, this more realistic, character-focused presentation also helps encourage empathy and investment in user success (Guenther, 2006). In theory, design teams and other stakeholders will come to know personas by name, intuiting their needs and preferences, and use the personas as a common language for discussing users and making choices during the design process.

These qualities made personas a good choice to address problems in the way we at Utah State University Libraries were managing and designing our website, helping us better understanding users’ needs, and by extension, helping identify the core features our website needed to include in order to better meet those needs. Previously, the library had no common or consistent understanding of library users, and as a result, web design was essentially haphazard, with no clear goals or vision. The term “user” meant something different to each staff member, and was strongly influenced by personal experience, preferences, and assumptions. For example, due to their regular exposure in the classroom, an instruction librarian might have a traditional undergraduate student in mind when thinking of users, whereas staff in resource sharing traditionally work with graduate students and faculty, shading their understanding of common user needs. These differences would often lead to project goals being unfocused based on different stakeholders’ perceptions of the target audience. For a user-centered process to be successful at our library, we clearly needed to move away from fluid definitions of users, and instead determine exactly whom we were designing for and what attributes should be the focus of decision making.

How Personas are Made

To accurately reflect users and encourage personas to be taken seriously by internal stakeholders, a data-driven approach is often recommended for persona creation, using either primary or secondary information about users (Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). Primary data is often collected through direct observation or interviews with target users where they openly discuss their thought processes or feelings about using a product. Firsthand observations of users, especially within the environment or context where a product will actually be used, provide the most accurate data from which to create personas (Goodwin, 2002). Secondary data, by contrast, isn’t gathered directly from users, but is instead filtered through some third-party source. For example, while it can be extremely valuable to elicit insight from staff who frequently interact with users, this information is considered secondary because it is a step removed from actual users.

While data-driven personas are ideal, there are advantages to drawing from experience and assumptions to inform persona creation. Assumption personas are quick and easy to create, and encourage reflection in the design process. For example, Donald Norman reported success using assumption-based personas to help designers get a fresh perspective and develop empathy with their target audience, which ultimately led to more thoughtful designs (Norman, 2004). The process of gathering assumptions can also be useful, exposing tacit knowledge and suspect or contradictory ideas about users, indicating where more research may be needed (Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). For example, we assumed the core audience for the library’s discovery layer was inexperienced undergraduate students, not graduate students and faculty. However, after reviewing survey feedback, it became clear that a wider group was using the discovery layer for known-item and other quick searches, significantly changing how we managed this tool.

No matter what type of data you use to inform persona creation, data collection does not have to be a time-consuming process, as Pruitt and Grudin (2003) showed in their use of existing market research. Both primary and secondary data can be drawn from previous research efforts, conducted internally or from an external source, allowing for quick analysis and “draft” personas to be made. Such personas can then be refined by additional primary research in order to create more valid representations of users, as we will describe in this article. One significant benefit to this iterative approach is that personas will continue to grow and improve as new data and research are incorporated.

After data are collected about users, there are a number of ways to go about forming personas to represent those users. When evaluating a large amount of data, Pruitt and Grudin (2003) recommend divvying up data sources among the team members who will be participating in persona creation. Next, methods such as affinity diagramming can be used to compare and find relationships between the data sets, helping form the foundation of unique user personas. In affinity diagramming, interesting facts, trends or other pieces of data are pulled out and written on cards or sticky notes, which are then arranged as part of a group exercise. This quick method of persona analysis is useful because it works well for diverse data source types and is highly collaborative (Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). The behaviors and personality types that emerge from these kinds of exercises are then enhanced by adding a persona name and other fictional biographical details to make the persona feel realistic. Because personas are meant to aid the design process by reflecting common behaviors and goals, Guenther (2006) recommends limiting the number of personas to a small set of characters representing broad user patterns.

Drawbacks of Personas

There are some limitations and drawbacks to using personas that should be kept in mind. As Cooper (1999) notes, designing for one well-understood person is far more successful than trying to design for each and every potential user. But by distilling diverse people into a handful of characters, personas can potentially obscure important differences among individuals in favor of characteristics that support broad-based design. Thus, it is important to recognize that personas are a form of stereotyping, whether positive or negative, which have the potential to legitimize and exacerbate the effect of personal biases in the design process (Turner & Turner, 2011). Persona creators can limit this risk by ensuring that solid research is used to inform persona characteristics, rather than relying on potentially faulty assumptions.

Personas, if not properly designed, also pose a risk of being viewed as unnecessary and may be quickly abandoned by an organization. Long, unfocused persona biographies discourage team members from reading and remembering the persona (McKay, 2011). This can lead to personas being viewed as “fake” and irrelevant to the design process. To keep personas relevant, McKay recommends creating simple documents that focus on traits and behaviors that are important to the design process, while limiting personal back story. Incorporating user research into persona documents, especially observational research that elicits the user’s voice, can also encourage team members to trust and actively use personas in the design process (Edeker & Moorman, 2013).

Finally, personas are most successful when combined with other user-centered research and design practices, and customized to fit a specific context or user community. A set of personas developed for a specific aspect of the library user experience may not necessarily transfer to other applications or areas of library use. As a best practice, libraries should encourage different units and service areas to pick and choose the individual personas that are most relevant to their area, expanding on those personas or creating new ones as needed, and initiating their own research projects to learn about different target audiences.

How Libraries Have Applied Personas

While library & information science authors have been advocating for the use of personas for many years (Cunningham, 2005; Phillips, 2012; Schmidt, 2012), they don’t appear to be in widespread use among libraries, especially public libraries. However, as interest in user-centered design grows, libraries continue to experiment with personas as a way to introduce user-centered approaches into library practice. Fox refers to personas as a “proxy stakeholder and an advocate for their proxied constituents,” (Fox, 2014, p. 70) and notes that the process of creating personas can be as useful as the personas themselves. Most commonly, personas are used by libraries to improve the web design process (Ballard & Teague-Rector, 2011; Cunningham, 2005), but have also been used to inform web and overall library strategy (Koltay & Tancheva, 2010). Personas have been applied in order to better understand users in a number of unique library contexts, including medical library users (Brigham, 2013), users of an institutional repository (Maness, Miaskiewicz, & Summer, 2008), humanities scholars (Khaled Al-Shboul & Abrizah, 2014), and adult distance education students (Lewis & Contrino, 2016).

Many different approaches and data sources have been used to develop library personas, including surveys and other user assessments (Cunningham, 2005), text analysis of user interviews (Maness, et al. 2008), software analysis of chat reference transcripts (Tempelman-Kluit & Pearce, 2014), and a mix of ethnographic techniques using undergraduate students as data collectors (Zaugg & Rackham, 2016). Although personas have been applied in a variety of settings, many have argued for a more simplified approach to persona development (Fox, 2014; Guenther, 2006; Koltay & Tancheva, 2010), which could allow for more libraries to create and adapt personas. This article is intended to address this need by proposing a practical model for quickly creating and putting personas into practice. Additionally, our approach advocates for iterative personas that change and improve over time, keeping personas relevant and reflective of the user community, while supplementing ongoing design and UX work.

Our Approach to Persona Creation at Utah State University Libraries

In 2014, the library’s new web services librarian created a working group to explore ways to improve the current web design process by incorporating more user-centered methods. This group would serve as the “core team” described by Pruitt and Adlin (2010) as a key part of the “persona family planning” phase of persona development. During this stage, a diverse team is assembled and engages in a kind of “organizational introspection” to expose underlying needs and identify potential persona types that will be needed to meet those needs. To better leverage the experience of librarians, particularly those that worked closely with students and faculty, our team included several members of our reference department, as well as programmers from our systems department. Based on discussions with the working group and other staff who had been involved in website planning throughout the years, the group identified several problems with how the website was being designed and managed:

- Website improvements were generally made as part of a major redesign, which were time-consuming and infrequent, making it difficult to make necessary UX improvements or incorporate insights from user research.

- Web design and development was largely driven by internal preferences and assumptions about what users needed, not a firm understanding of actual user needs.

- Our understanding of users and their needs varied significantly due to the diverse backgrounds and experiences of library staff members, making it difficult to collaborate and form consensus around web development matters.

- The knowledge and experience of front line staff and others with a strong understanding of user needs wasn’t being heavily incorporated in the design and development process.

To address these problems, the group decided to adopt an iterative, continuous approach to website design. In contrast to a major website redesign, continuous design allows for high-priority problems to be addressed immediately and introduces major changes incrementally over time, creating less disruption for users and reducing staff-level conflict resulting from large-scale redesigns (Schmidt, 2011). In addition, personas were identified as a useful way to re-orient our process away from a staff-centered focus, and toward more broad user-centered goals. To achieve this, we wanted our personas to represent all important user populations within our community, including undergraduate and graduate students, faculty members, and community/public patrons, showing where users’ needs both overlapped and deviated from each other. This would help us satisfy broad user needs in cases like the website homepage, while in other cases helping us keep in mind more unique, narrower needs, such as for pages geared for interlibrary loan or other faculty-oriented services. To create the personas, we chose a lightweight approach that would complement our web development process and allow us to put personas into practice sooner rather than later. The goal was to establish a basic definition of our target users using data that could be gathered quickly and easily. In addition, we wanted to incorporate the collective knowledge and experience of our library staff as a way to foster collaboration and include a broader range of voices in our web development process. Although it was important to take any assumptions with a grain of salt, we considered frontline staff and others who commonly interacted with patrons as user “informants,” who could provide particularly valuable information about users’ common needs and frustrations.

We also hoped personas could help us better reflect and meet the needs of less visible users. With 12,459 distance learners for the 2015–2016 semester, USU Libraries are increasingly serving patrons who have minimal direct interaction with library staff. Personas could also help formalize our understanding of this diverse patron group, as well as undergraduates in general, who we often think of as a single, homogenous bloc. Knowing that personas are in essence a form of stereotyping, it was important that our process drew from evidence to illustrate underlying needs and motivations, and not simply use academic status or other demographic details to distinguish different types of personas. However, we recognize that some assumptions had to be made where we lacked extensive data for certain groups, such as university faculty. We plan to address these flaws by incorporating future research to more accurately better reflect these and other less visible users.

To help personas remain accurate and reflective of the target audience, Pruitt and Grudin (2003) encourage user research to be collected and incorporated into personas as an ongoing practice. With this in mind, our team decided to separate persona development into two distinct phases, relying first on previous assessment and usage data to create basic personas, followed by usability tests and interviews with students, and the incorporation of feedback from librarians and other staff to validate and further refine the personas. In addition to several phases of data collection and refinement, we plan to regularly review persona documents to ensure they continue to reflect our changing user population and technological landscape. This iterative and adaptive approach provides a good middle ground between highly data-driven and purely assumption-based persona methods, allowing libraries to create basic personas that can evolve over time and work in concert with continuous design and agile development methods.

Persona Development Phase One

Before creating personas, Pruitt and Adlin (2010) recommend assembling data from a wide variety of sources, both primary and secondary, showing some insight about users and their behaviors. To begin, we drew heavily from previous assessment and usage data, including reference desk transaction summaries, transcripts of reference chat transactions, user comments from the 2013 LibQUAL+® survey, and results from a 2014 usability study conducted by our former assessment librarian. These sources were selected because they were convenient and readily accessible, and provided the following:

- A broad range of users’ library needs, frustrations, and behaviors.

- The resource/service requests, reference questions, or requests for assistance that were asked for most often.

- Users’ thoughts and feelings about library services, including desires for improvement, provided in their own words.

For the full list of data sources included in phase one, see table 1.

| Data source | Data type | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Reference transaction summaries | Secondary |

|

| Chat transcripts | Primary |

|

| User comments from 2013 LibQUAL+® Survey | Mix |

|

| 2014 usability study results | Mix |

|

Data Analysis

Prior to reviewing our data sources, some assumptions were made about users in order to help with the analysis and organization process. For example, following the recommendations of Pruitt and Adlin (2010), we drew from our knowledge of users to identify important user categories, including undergraduates, graduates, faculty, and distance users that would help group our data and guide the persona development process. Over a period of two weeks, group members reviewed data for outstanding comments, requests, behaviors, and statements that illustrated some aspect of users’ underlying motivation or goals when interacting with library services. Data sources were divvied up, with all members reviewing data from our 2014 usability and 2013 LibQUAL+® studies, several members reviewing reference chat logs, and only one group member reviewing reference summaries. Comments and themes from each data set were collected in a master document in a relatively raw, unstructured format, either using direct quotes from users or summarized by the group member analyzing the data. This allowed each member to review the themes as a whole and refer back to the original source if necessary.

Divvying up the data sources, a method Pruitt and Grudin (2003) also employed, allows for a large amount of data to be reviewed quickly, but may result in a more biased analysis of the data. While this may have undermined the validity of the results, it allowed data to be analyzed more efficiently, our main goal at this stage. Because most of the sources used in this initial phase were primary sources, we considered this a reasonable trade-off, allowing a basic outline of personas to be developed with limited investment. In addition, all of the sources, with the exception of the 2014 usability survey, reflected the needs of highly motivated patrons either requesting help or providing feedback. In both cases, these data may not reflect the broader population of users, who may be less likely to request assistance or report feedback. In phase two, targeted interviews and usability tests allowed for more direct observation of library users to be incorporated into our persona development process.

Reference Transaction Summaries

Summaries of 5,482 reference desk transactions were downloaded from the Springshare LibApps platform for the time period July 22, 2013 – November 2, 2014. From this set, we selected 40 transactions tagged as “faculty/staff” and 30 tagged as “graduate students,” pulling sets of 5 in intervals of 100. We also selected 100 transactions tagged as “undergraduates,” choosing sets of 10 in intervals of 400. This presented us with a broad snapshot of users’ resource and service needs, including what problems and frustrations were commonly encountered, but reduced the amount of time and effort needed to review a large set of data. In addition, all 77 transactions tagged for our regional campus locations or distance users were selected to ensure we were accurately representing this important population.

The transaction summaries were then reviewed in detail by the assigned group member, with information related to the type of request or resource needed, as well as user information and characteristics about the patron recorded by theme (table 2).

| Data group | General theme of question |

|---|---|

Undergraduates (4065 total) 100 reviewed | Room locations; study rooms; course reserves; citing sources; identifying credible sources; finding full text; locating articles on a specific topic; looking for textbooks; looking for a specific book; articles; specific USU-related info; hours of library; scanner; LibGuide; printing |

Faculty/Staff (766 total) 40 reviewed | Finding books/journals; streaming video access; Visiting faculty orientation; access to computers; course reserves; request for library instruction; accessing resources online; citation management software; interlibrary loan; copyright |

Graduate Students (574 total) 30 reviewed | Comprehensiveness of research; looking for a specific book; citation software help; research help for subject specific research; accessing resources online; thesis binding; interlibrary loan |

Regional Campus and Distance Education (77 total) Reviewed all | Accessing resources online; login problems; interlibrary loan; general research questions; thesis binding; locating articles on a specific topic; upper-division research on specific topics; streaming video access; Encore problems; course reserves |

Chat Transaction Logs

Chat transaction logs for two months were downloaded from the LibApps platform for August 25, 2014 – November 3, 2014, totaling 724 transcripts. The group member assigned to review chat transcripts recorded themes and perceived user characteristics that stood out from the transaction data, which were used to develop a coding schema that was applied to the data. Because the chat logs were considered primary data, two other group members independently coded the transcripts to confirm the analysis. The coded transcripts where then compared to find characteristics that seemed to commonly occur together in order to identify trends and relationships that could be used to inform persona outlines. This constituted a kind of mini-affinity mapping exercise, a technique we later applied to our data as a whole to identify related characteristics. Using this method, two distinct approaches to research questions and other requests were apparent, reflecting different levels of comfort or experience with libraries and the research process among the users in our analysis. For instance, a chat user that wanted quick answers also commonly mentioned their assignment requirements, such as needing a certain number of sources or format types for their bibliographies. Their research questions were also less focused and required more elicitation on the part of reference librarians. Similarly, users with more focused research questions were commonly more willing to engage in longer and more in-depth chat sessions, and might also be referred to a subject librarian for more help. These distinctions suggested that highly motivated and engaged users are also more experienced with library research, while less experienced users either have less in-depth research needs, or simply don’t want to spend a lot of time engaging in the reference process. These relationships were important in forming our basic personas, while characteristics from the chat transcripts were used as inspiration for our persona’s representative quotes. Access problems and issues with our Integrated Library System (ILS) seemed to span across both types of users, making this a common frustration featured in our final personas. Table 3 illustrates characteristics that commonly appeared together in our group analysis.

| Research questions | Answer time | Type of request | Willingness to contact | Access issues | ILS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inexperienced | Broad or unfocused research questions | Want quick answers:

| Concerned with assignment requirements:

| Worry about “bothering” librarians | Trouble-shooting access issues from off-campus | ILS issues |

| Experienced | Focused research questions | Willing to take time to work on complicated questions |

| Often (eventually) referred to subject librarians |

LibQUAL+® Survey Questions

In 2014, USU’s assessment librarian conducted a detailed analysis of open-ended comments from a 2013 LibQUAL+® survey and created reports for each major user type, including undergrads, graduates, and faculty members, which summarized each group’s perceptions and expectations of the Libraries, and included representative quotes. This data was selected because it was not only readily available, it also provided a rich source of primary information about users, related in their own words, regarding their thoughts and feelings about library services, including desires for improvement.

Each group member reviewed the assessment librarian’s reports, while several members also reviewed the raw survey data. Each member collected trends and themes from the data, including direct quotes, expressing common perceptions and feelings users expressed about library services, which were organized into our master document by user type. For example, comments from undergraduates, such as “make [the website] less cluttered” and “make things simple,” indicated that navigation and ease-of-use were important areas for improvement. Many undergraduates also felt overwhelmed by the large number of library resources and expressed confusion with starting the research process. Faculty members’ feedback indicated frustration with specific tools, like the catalog or electronic journals, with comments such as “it often retrieves irrelevant items” and “could be more logical and user-friendly,” while praising the value and efficiency of services such as interlibrary loan. Interestingly, many graduate students expressed a desire for more library instruction and research tutorials to help them use library resources more effectively. All patron groups expressed a desire for a more usable website and easier access to the materials they needed most.

User Survey and Usability Tests

Our analysis also included data from two open-ended questions from a 2014 survey of 114 undergraduate students recruited from an introductory English course at our main campus location. The survey occurred before they had received any formal library instruction. The first open-ended question asked, “You have to write a paper for a class. How do you go about getting information and resources for your topic? List everything you can think of.” Google and search engines were mentioned in 78 percent of responses, usually first. Library databases or other e-resources were mentioned almost as often (76 percent), and librarians or other experts were listed in 21 percent of responses. Other information sources included the student’s professor, textbook, the course management system, friends, family members, and peers.

The second open-ended question asked, “How could we improve the library website? Is there anything specific we could do to help you find the information you need for classes?” Common responses included a desire for quick access to commonly used resources and features, greater simplicity, and easier navigation. Negative comments noted that the website had too much information, was cluttered and disorganized, and lacked information for basic questions like how to find books in the stacks. Users also commonly expressed feelings of being overwhelmed and confused by the library, mirroring comments from our LibQUAL+® data. In addition, students expressed a desire to be more effective at using the library without needing help from library staff.

Along with survey questions, formal usability tests with ten undergraduate students were also conducted as part of the library’s 2014 study. Results from these tests provided valuable information about how less-experienced users approached research topics and interacted with library resources. Together with the survey questions, data from this study confirmed many of the trends found throughout our data analysis, providing a strong sense of the needs, behaviors, and preferences of undergraduate students, a key user group for USU Libraries, and an important category that we wanted to reflect in our user personas.

Affinity Diagramming

After collecting data from their assigned sources, along with comments from the LibQUAL+® survey and our 2014 usability study, group members reviewed and discussed common trends and attributes that stood out from our master document. Next, the group conducted an affinity diagramming exercise in which each theme, trend, or attribute was written on a sticky note and posted on a large wall. Group members then worked together to arrange similar sticky notes into related clusters. Over several rounds of connecting and combing similar notes, the clusters eventually could not be further condensed and were each given a general label. The following clustered emerged from our exercise:

- Need for speed

- Tech/online

- Overwhelmed/stressed

- Confused

- Library as place

- Feelings

- Personal network

- Outsider/regional campus

- Shy/introvert

- Traditionalist

- Wants personal help

- Open to help

- Novice researcher

- Advanced/proficient researcher

- Busy/convenience

- Independence

- Positive relationship with library

Each cluster represented several interconnected themes or attributes. For example, under the “need for speed” cluster, team members grouped attributes such as “quick search/easy to find,” “wants quick answers,” “impatience,” “only cares about practical info (hours, study rooms).” The tech/online cluster included attributes such as “tech-savvy,” “avid texter,” “loves smart phones,” and “social media.”

After the affinity mapping exercise, the group started to make connections between clusters and formulated rough outlines for initial user personas. For instance, the “need for speed” cluster could be easily connected within the “novice researcher” cluster based on the relationships that emerged from our analysis of chat reference transcripts. Other behaviors and attributes, however, were more difficult to connect. For example, attributes from the “traditionalist” cluster, which included resistance to change and a preference for print formats, weren’t obviously connected to other clusters. Due to the disparate nature of our data, and the fact that it was not based on our own direct observation of users, making connections between our clusters did not lead to distinct outlines for personas. Instead, based on recommendations to keep personas simple and focused on addressing design needs (McKay, 2011), we decided to further organize our affinity clusters into four broader categories that we felt had a strong influence on a user’s overall success in using the library website:

- Research: The user’s level of skill in scholarly information seeking and knowledge of scholarly practices in their field of study.

- Technical: The user’s level of skill with using technology, both in terms of proficiency with computers and web technology, and as specific skill using library systems.

- Emotional: The user’s level of comfort or anxiety when conducting research or using the library, and feelings of being overwhelmed, confused, or frustrated with the library experience.

- Location: The location where the user primarily conducted research or engaged with library resources and services. Due to USU’s large population of distance and regional users, we identified location as having a high impact on their ability to easily access and use library resources and services, as well as the nature of users’ interactions and relationship with the Libraries.

Table 4 illustrates how the attribute clusters mapped to each of these categories.

| Category | Attribute clusters |

|---|---|

| Research | Advanced/proficient researcher; Novice researcher; Personal network; Traditionalist; Wants personal help; Open to help; Independence |

| Technical | Tech/online; Need for speed; Google; Busy/convenience; Traditionalist; Independence; Advanced/proficient researcher; Novice researcher |

| Emotional | Overwhelmed/stressed; Shy/introvert; Confused; Feelings; Positive relationship with library |

| Location | Library as place; Off campus; Outsider/regional campus; Independence |

While user personas weren’t immediately apparent, these categories helped focus persona development around core design needs relevant to the library service experience. Because they could be mapped along a spectrum (e.g. novice researcher, intermediate researcher, advanced researcher) or binary (e.g. near location, far location), attributes from each category could be mixed in varying degrees to develop the skeletons of our personas. This allowed us to form persona types that would include the full breadth of characteristics that seemed necessary for our design needs. In addition, this scheme allowed us to mix attribute clusters across several high-level categories, for example, traditionalist was placed under both research and technical, reflecting the multiple areas where those attributes were observed.

Creating Initial Personas

To get the process started, each group member was assigned to create two personas, drawing attributes from each of our categories to form the basic outline for each personality. Following the “family planning phase” of the personas creation process outlined by Pruitt and Adlin (2010), we already had in mind an initial set of user types that we considered important to represent in our personas. Thus, we decided to create personas matched to our key groups within our user population: undergraduate students, graduate students, faculty and instructors, and our community patrons. The goal was to represent a broad range of users and needs, using a mix of attributes from our affinity diagrams, and later pare the number of personas down to a more manageable and usable set. It was also important to represent our attribute categories at varying degrees across each of our persona types. For example, for each of the persona types we outlined, we created a separate persona to reflect both novice and advanced research skills, and different levels of emotional connection and comfort with library services, using a mix of attributes from each category to illustrate each persona.

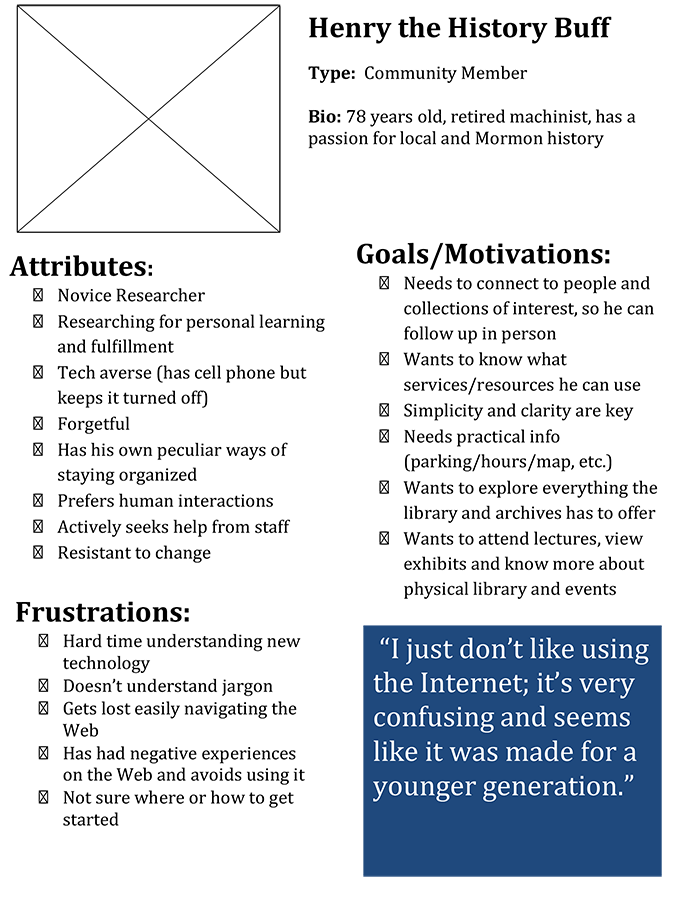

The user attributes from each of our categories were incorporated into the proto-personas under three sections labeled “Attributes,” “Frustrations,” and “Goals/Motivations.” To help flesh out the personas and make them seem like real users, fictional details such as a major/department, and other biographical information were added, along with goals, frustrations, and a representative quote, which were based partly on data, and partly on knowledge and past experiences with users. While biographical details help make personas more relatable, it is important to remember that these are merely examples that are certainly not representative of all the real people who could be affiliated with that persona. Not all undergraduate students, for example, are inexperienced researchers, or education majors for that matter.

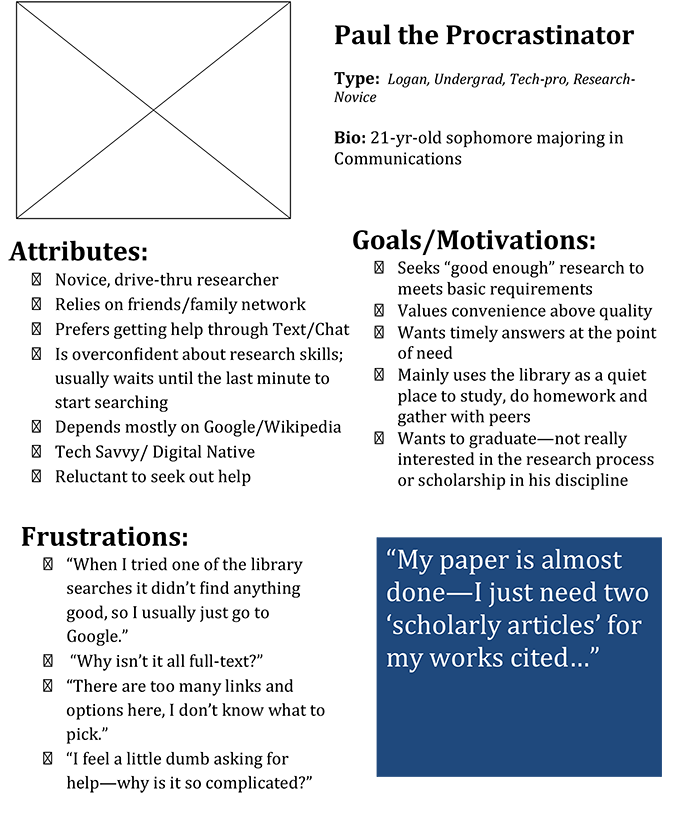

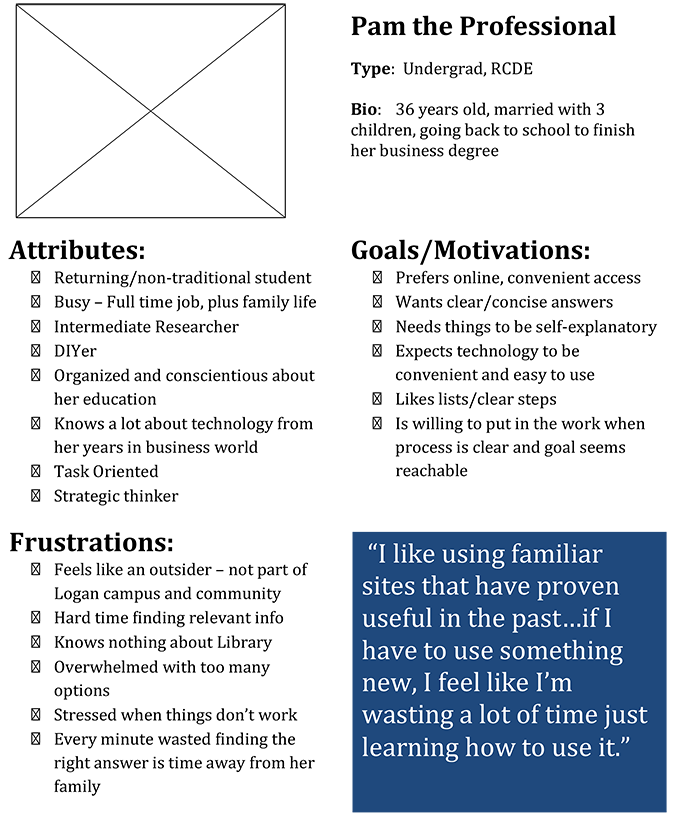

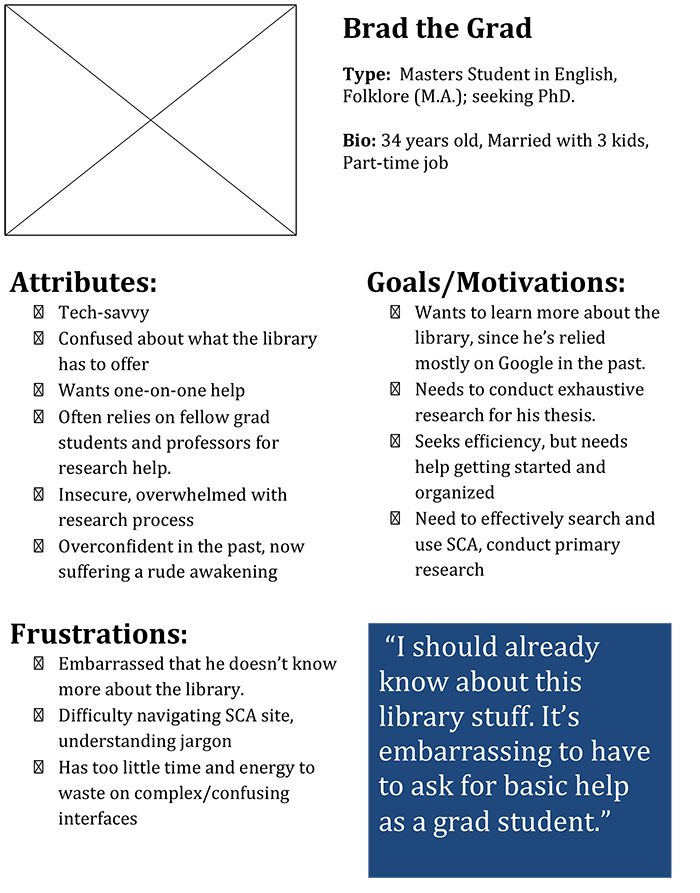

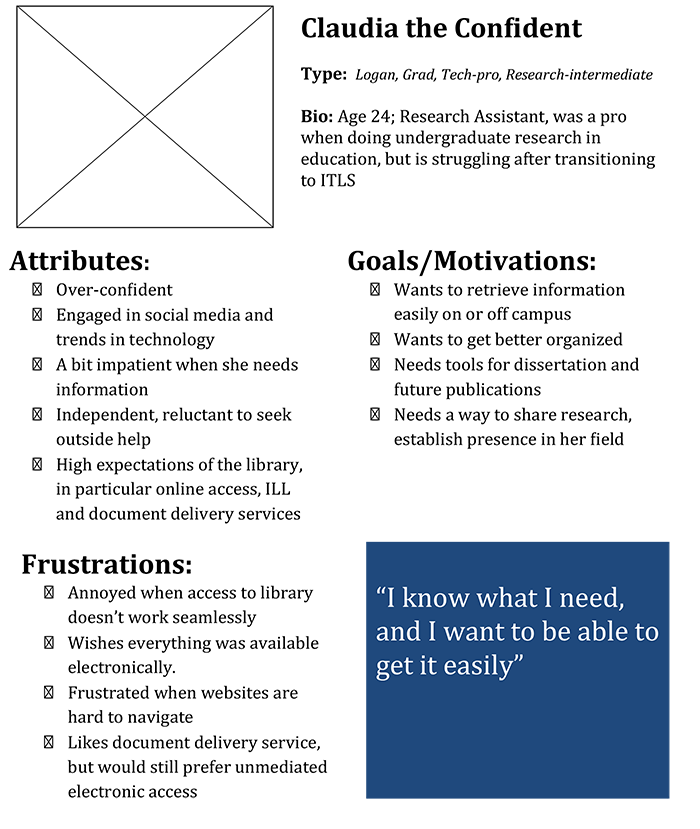

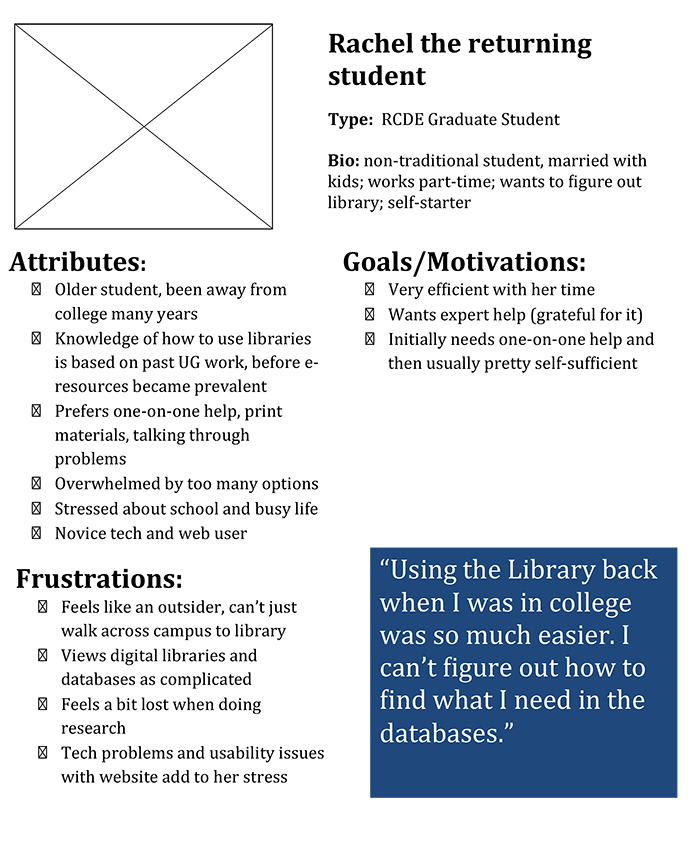

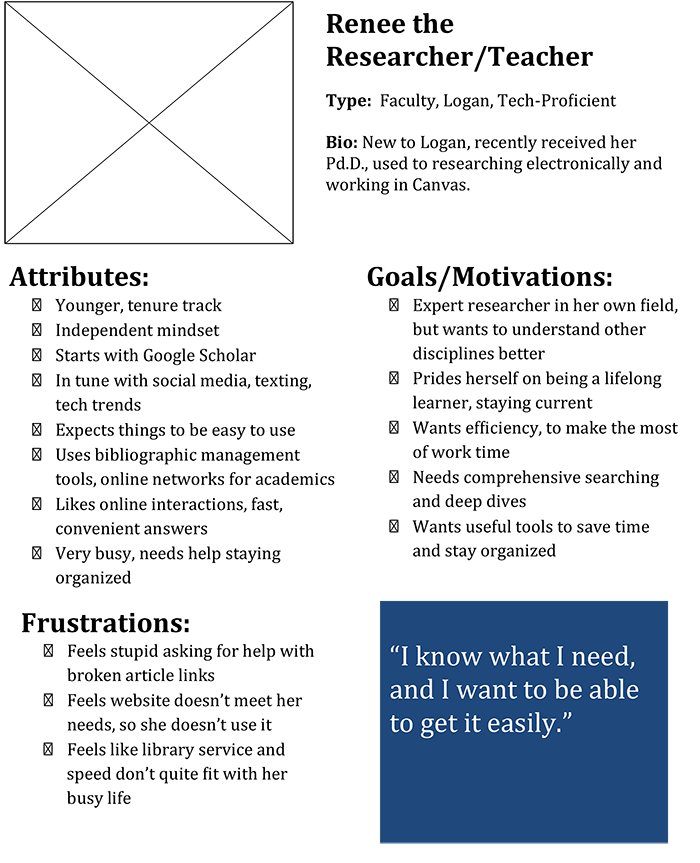

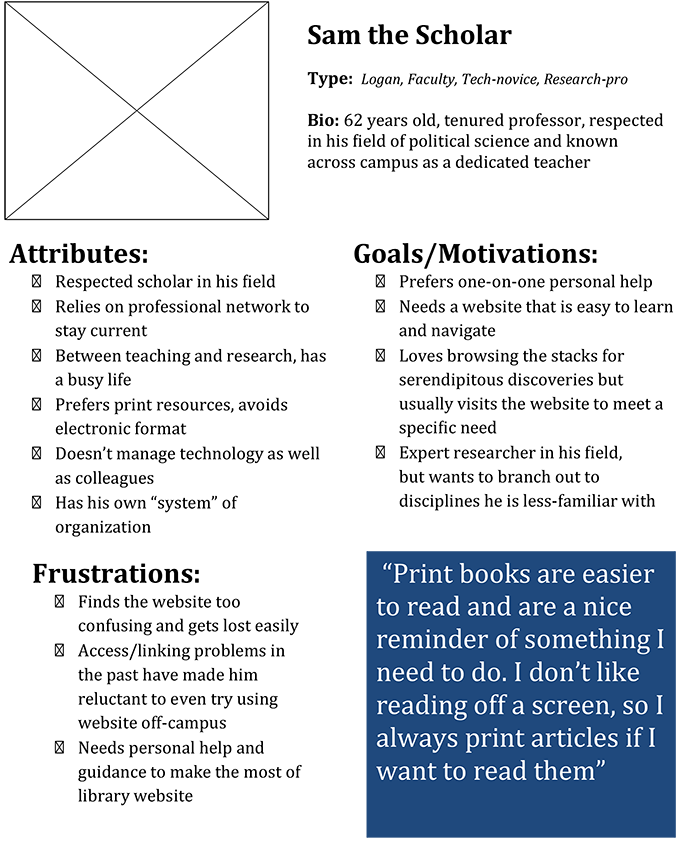

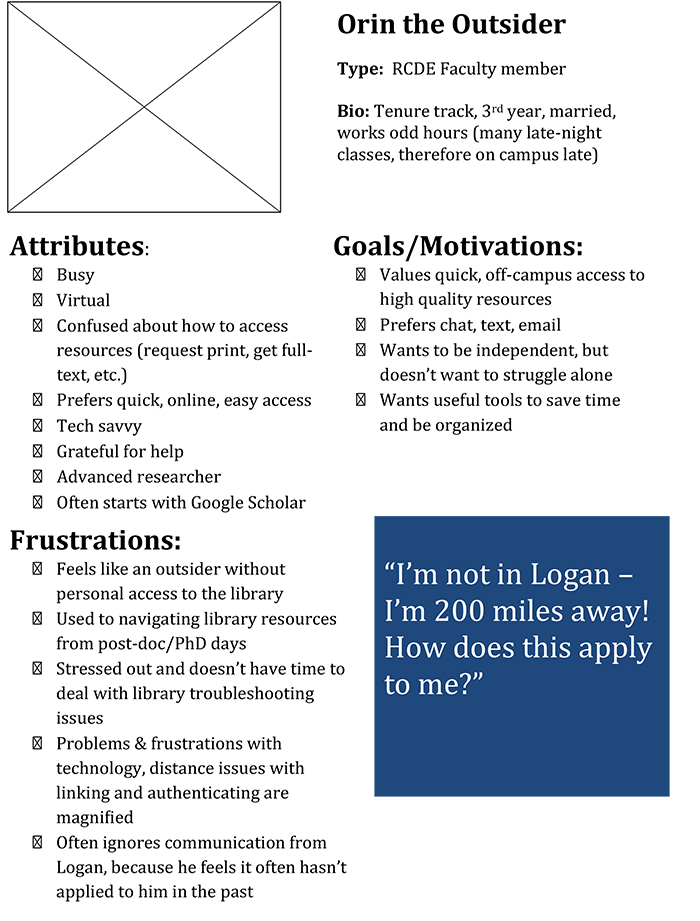

To keep our set of personas small and focused on representing broad user needs, we compared and combined each of the personas created by the group into a final set of nine initial proto-personas. These represented each important user type we identified, as well as different levels of research, technical, emotional and location-related attributes (figs. 1–9). In all, two undergraduates, three graduate students, three faculty members, and one community member were kept in our final selection. Although undergraduates make up the majority of our user population, we felt our graduate student personas could also stand in for more advanced and academically motivated undergraduates, so only two undergraduate personas were kept. The group also felt that only one community member persona was necessary to adequately meet the broad design needs for our main website.

This initial round of persona creation was by no means a complete picture of our user population. While we had a lot of data related to the needs and approaches taken by undergraduates and graduate students, we had to draw from experience and make assumptions to fill in details for our faculty and community-oriented personas, making these inherently less reliable. As a future step for improving our personas, we plan to collect additional data to help validate our assumptions and improve our understanding of these groups. To avoid leaving the impression that specific user groups could only be associated with certain personas, we replaced our initial persona names based on user type with generic names that would suggest their general background, such as “Pam the Professional.” By downplaying user type and other biographical information that McKay (2011) suggests is unnecessary, we hoped our personas would illustrate how patrons from different disciplines, backgrounds, and educational levels could actually be very similar in terms of research behaviors, library use and needs, and other core characteristics.

Persona Development Phase Two

To improve our basic personas, the group felt we needed to validate the conclusions drawn from our initial data set and incorporate a more complete and consistent voice of library users. We also felt it was important to include more perspectives from our regional campus and distance users, which are key to USU’s land-grant mission, as well as undergraduate students in general, in order to develop more diverse personas. To address this weakness, we decided to conduct in-depth interviews and usability tests with students at one of USU’s regional campuses in the second phase of our persona development process. We also subjected our draft personas to several rounds of review by subject librarians and all library staff members, with subject librarians in particular being asked to validate our assumptions against their knowledge and experience.

Interviews and Usability Testing

Brief interviews and usability tests were conducted with eleven undergraduate students at one of USU’s regional campuses, using questions based on a persona creation project conducted by North Carolina State University, which was specifically focused on library users, and could be easily adapted for our purposes (NCSU Libraries, 2010). Over the course of a thirty-minute interview, students were asked about their online habits, perceptions of the library, the services they used, and what they typically did at different stages of the research process. See the Appendix for the complete interview questionnaire.

Speaking with and hearing from students directly allowed us to develop a better sense of the student voice and perspective, which was difficult to glean from the disparate data in our initial analysis. Quotes from these interviews were adapted into both of our undergraduate-focused personas. Interviews and usability tests also provided insight into students’ academic habits, validating much of what we anecdotally understood about traditional undergraduates, namely that web usage figures heavily into their daily lives, including their academic work and research. We also learned that while some regional campus students had unique needs and approaches, in many ways undergraduate students shared a lot in common, regardless of how or where they took classes. A more important factor was whether a student was traditional college-aged or a more non-traditional, returning student. Compared to the traditional students we interviewed, returning students spent more time planning and actively sought help with research projects in advance. In this way, returning students and other advanced undergrads were very similar to graduate students. This validated our chat transcript and reference desk analysis, confirming that research experience, motivation, and user effort were all-important variables for distinguishing personas types.

Staff Feedback and Validation

As an additional step to help improve our personas, our nine draft personas were given to subject librarians and displayed prominently on large posters in the staff break room for critique and feedback. This area is accessed by nearly everyone who works in the library—faculty, staff, and student workers, and all were invited to contribute to and comment on the personas. While staff are certainly a secondary data source when it comes to understanding library patrons, Pruitt and Grudin (2003) encourage tapping into those that have strong knowledge of and experience working directly with users. Drawing on staff as “user informants” not only provided a rich source of experiential information about users, it was also a great way to introduce personas and encourage buy-in from groups who otherwise might not have been engaged in the process. While this feedback was useful for filling in gaps in our understanding of faculty members, graduate students, and other advanced library users, it cannot replace the role of observational research in truly understanding users from their own perspectives (Edeker & Moorman (2013).

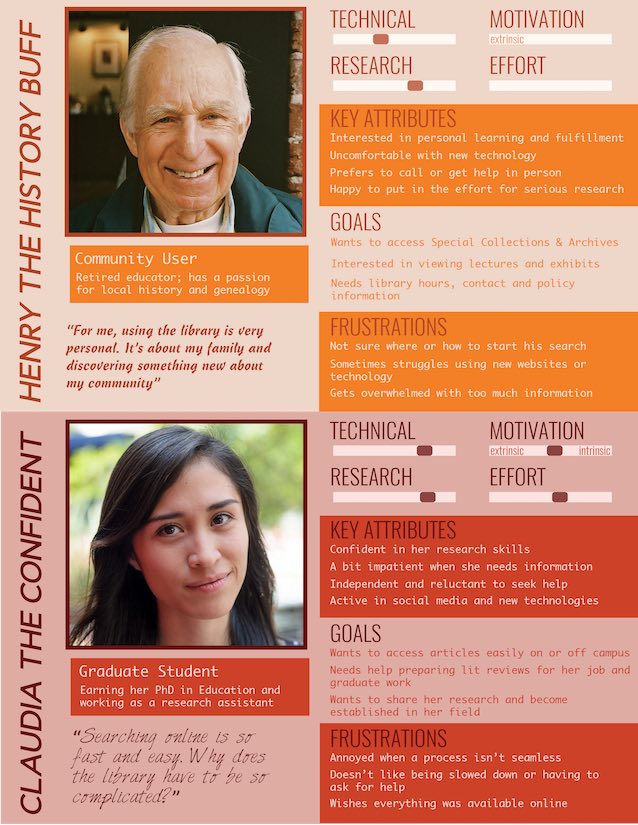

Final Personas

After analyzing feedback from staff, and incorporating more information about undergraduates from our interviews, the group reconvened to finalize our draft personas. It was clear that there was too much overlap between our original personas, and to ensure we had an effective, memorable set, we decided to fold characteristics of our regional and online users into our traditional undergraduate and graduate student personas. The remaining six personas were refined through several rounds of editing and condensed to fit into a smaller, trading card style format (see figs. 10–12). These pocket-sized personas were printed and distributed to every library department and several conference rooms, making them easy to bring to meetings or pin around our desks, and helping encourage staff to actively adopt them. Pruitt and Grudin (2003) reported success using similar strategies, printing personas in a variety of formats to help evangelize persona information and use. We are still assessing whether this format has been successful and what more might be needed to encourage persona adoption.

The front of each persona includes a name, biographical information, a picture to help illustrate the character, and a quote based on real comments from our interviews and assessment data. On the back, persona characteristics are categorized as key attributes, goals, and frustrations, as well as sliding scales representing the persona’s relative level of research skill, technical skill (which we define as including both general technology literacy, and specific literacy with library technology), and personal motivation and effort. These scales are largely assumptive, reflecting a possible range of levels within our user community. In the future, these scales are one area that could be improved with data, for instance, a systematic analysis of reference transactions, similar to the persona project from New York University (Tempelman-Kluit & Pearce 2014).

So far, our personas have proven to be a practical and easy to implement tool for our web design process. Our persona trading cards are a common sight at design meetings, and have been particularly useful during the earlier stages when project needs are being identified and discussed. Personas are used to evaluate everything from copy and content, to layout and visual design of the page. By starting with our personas, stakeholders are forced to analyze the target user audience by prioritizing which users should be the focus of the design, and what information and features are necessary to meet their goals. For example, when planning the design of a landing page for our digitized collections, we identified students, community users and faculty as important users. But after analyzing our personas and considering their unique goals, it became clear that faculty would have very different needs related to scholarly communication and the institutional repository. This clarified the purpose of the design project, illustrating a need for two separate pages, one focused on educating and promoting the repository to faculty, and another where the repository was presented as a distinct collection. In the future, we plan to apply personas more broadly to the entire library user experience, including both digital and in-person interactions and services. For example, journey maps could be created to illustrate different stages where personas interact with the library, showing critical points where users struggle, and helping improve the overall service experience.

There’s a lot of room to improve how well our personas reflect knowledge of different users within our community. For instance, by nature of the service points and sources we were analyzing, the data were more focused on undergraduate and graduate student populations. These are certainly not the only important user groups for our library. More data, particularly observational research into faculty members and other less visible user groups, will help ensure our personas reflect greater diversity, while limiting the influence of assumptions in design process. Knowing that our user community is constantly changing, it will also be important to ensure our personas continue to represent growing needs and new patterns of use. As we learn more about our users, drawing regularly from staff feedback and ongoing user research, our personas can be refined in order to stay relevant, both as a reflection of our users, and a practical tool for the design process.

In addition, some technical improvements could be made to make the personas more usable as a design tool. For example, in order to limit the risk of personas being used to stereotype users, the biographical details might be updated to make it clear they are only examples and suggest ways in which a persona could be affiliated with multiple user types. Supplemental and supporting documents, for example instructions explaining the purpose of personas, or showing how to use them during design or assessment work, could also improve the likelihood that personas become a regular part of our practice.

Discussion

By establishing a concrete definition of users and their motivations and goals, personas provide a reminder to think deeply about users and keep them in mind throughout the design process. Instead of a vague, fluid definition of users, personas allow for a shared context and create a common language for user-centered design, making them particularly useful for the collaborative approaches often employed in library web design. Unlike reports and other communication tools, personas are also a highly relatable format for presenting UX research and encouraging staff to empathize with library users. Our low-cost approach to persona development draws heavily from existing user research and internal knowledge, which allowed us to quickly create and put personas into practice. Moreover, by treating personas as “living documents” that will be regularly refined with user research, persona documents can remain a reflective and relevant tool for our organization. In this way, we view personas as an important part of our UX strategy, providing a critical communication tool for ongoing user research and supporting our continuous design philosophy.

After adopting personas, we have already observed improvements in how we communicate and make decisions regarding the design and management of our website. By shifting focus to users as the standard for evaluating website success, we now have a clearer design philosophy, guided by better processes for designing and prioritizing web development projects. We also have a shared vocabulary for understanding users and communicating their needs—one that is meaningful for both programmers and service staff. This helps break down communication barriers and avoid misunderstandings, fostering collaboration and a culture where anecdotes, assumptions, and individual preferences are eschewed in favor of an evidence-based and user-focused approach to design.

Libraries have traditionally valued a user-focused and consensus-driven approach to the development and design of library collections and services. But as library professionals, it can often be challenging to distinguish our own preferences and assumptions from the real trends and needs in our communities, putting these values at risk. Personas, with their user-centered and team-oriented qualities, provide a practical solution to this problem, helping separate real from perceived needs, and offering a sharper lens for design and UX work in libraries.

References

- Ballard, A. & Teague-Rector, S. (2011). Building a library website: Strategies for success. C&RL News, 72, (3). Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/content/72/3/132.full

- Brigham, T. J. (2013). Personas: Stepping into the shoes of the library user. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 32(4), 443–450.

- Cooper, A. (1999). The inmates are running the asylum. Indianapolis: SAMS.

- Cooper, A. (2008). The origin of personas. Retrieved from http://www.cooper.com/journal/2008/5/the_origin_of_personas

- Cunningham, H. (2005). Designing a web site for one imaginary persona that reflects the needs of many. Computers in Libraries, 25(9), 15–19.

- Edeker, K. & Moorman, J. (2013). Love, hate, and empathy: Why we still need personas. Retrieved from http://uxmag.com/articles/love-hate-and-empathy-why-we-still-need-personas

- Fox, R. (2014). Dramatis personae. OCLC Systems & Services, 30(2), 69–73.

- Goodwin, K. (2002). Getting from research to personas: Harnessing the power of data. Retrieved from hhttps://www.cooper.com/journal/2008/05/getting_from_research_to_perso

- Goodwin, K. (2008). Perfecting your personas. Retrieved from http://www.cooper.com/journal/2001/08/perfecting_your_personas

- Guenther, K. (2006). Developing personas to understand user needs. Online, 30(5), 49–51.

- Harley, A. (2015). Personas make user memorable for product team members. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona/

- Khaled Al-Shboul, M. & Abrizah, A. (2014). Information needs: Developing personas of humanities scholars. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(5), 500–509. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.05.016

- Koltay, Z., & Tancheva, K. (2010). Personas and a user-centered visioning process. Performance Measurement & Metrics, 11(2), 172–183.

- Lewis, C., & Contrino, J. (2016). Making the invisible visible: personas and mental models of distance education library users. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 10(1/2), 15–29. doi:10.1080/1533290X.2016.1218813

- Maness, J., Miaskiewicz, T., & Summer, T. (2008). Using personas to understand the needs and goals of institutional repository users. D-Lib Magazine, 14(9). Retrieved from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september08/maness/09maness.html

- McKay, E. (2011). Personas: Dead yet? Retrieved from http://www.uxdesignedge.com/2011/06/personas-dead-yet/

- NCSU Libraries. (2010). Persona interviews for website redesign: User studies. Retrieved from: http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/userstudies/studies/2010personainterviewsredesign. NOTE: NCSU removed the persona project documents from their website, but the report is still available from the Web Archive.

- Norman, D. (2004). Ad-hoc personas & empathetic focus. Retrieved from http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/personas_empath.html

- Phillips, D. (2012). How to develop a user interface that your real users will love. Computers in Libraries, 32(7), 6–15.

- Pruitt, J., & Adlin, T.. (2010). The persona lifecycle: Keeping people in mind throughout product design. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Pruitt, J., & Grudin, J. (2003). Personas: Practice and theory. Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experience. San Francisco, CA.

- Rohrer, C. (2014). When to use which user-experience research methods. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/which-ux-research-methods/

- Schmidt, A (2011). Resist that redesign. Library Journal. 136 (4), 21.

- Schmidt, A. (2012). Persona guidance: The user experience. Library Journal. Retrieved from http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2012/10/opinion/aaron-schmidt/persona-guidance-the-user-experience

- Tempelman-Kluit, N., & Pearce, A. (2014). Invoking the user from data to design. College & Research Libraries, 75(5), 616–40.

- Turner, K., & Turner, S. (2011). Is stereotyping inevitable when designing with personas? Design Studies, 32(1), 30–44.

- Zaugg, H., & Rackham, S. (2016). Identification and development of patron personas for an academic library. Performance Measurement & Metrics, 17(2), 124–133. doi:10.1108/PMM-04-2016-0011

Appendix

Interview Questions (based on questions from NCSU’s persona project) NOTE: NCSU removed the persona project documents from their website, but the report is still available from the Web Archive.

- Background Information

- What is your class status/year in school?

- What is your major? If you haven’t declared a major, what area(s) are you interested in?

- Have you taken ENG 1010 or 2010 or have you ever had a class that visited the library or had a librarian guest lecture?

- Computer/Online Use

- Can you take me through your typical online routine? When you open up a web browser, what sites do you usually check out?

- Do you have any other favorite websites? (i.e. news sites, social media, email, etc?)

- Academic Information

- Describe a typical assignment for a class in your major. How do you approach that task?

- Library Information

- How often do you go to the library?

- How would you describe (your campus) library to a friend who has never been there?

- What frustrates you about using the library?

- How often do you go to the library website?

- What frustrates you about using the library website?

- You’ve been given an assignment to write a term paper on the dangers of sports with at least four sources cited throughout the paper.

- What is the first thing you do?

- How would you look through results to determine the four sources you want to use?

- What is the thing that makes you most nervous about this assignment?

- How would you fit those sources into your paper/argument?

- You have been given two weeks to complete this assignment. When would you typically start?

- When was the last time you talked to a librarian? What was the conversation about?

To create your own personas based on our design, see our persona templates.