Stressful experiences are associated with greater PTSD and depression symptoms

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

There has been extensive research conducted on how stressful events and traumas are associated with depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. However, very little research has investigated the association between exposure to stressful events/traumas and depressive and post-traumatic symptoms in a healthy, nonclinical population of adults. Our study examined relationships between exposure to stressful events/traumas, posttraumatic stress, and depression symptoms in a healthy, nonclinical sample of adults. While participants did not meet diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, our results suggest a positive relationship between the number of different lifetime stressful events/traumas reported and both depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms. These findings suggest that people who experience a greater variety of different stressful events/traumas during their lives report greater depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms in response to those events.

Introduction

Stress exists as a range or continuum, with positive stress on one end, and trauma on the other end.[1] Stress can be associated with positive emotion when it motivates us beyond our normal limits to accomplish goals, but it can also be associated with negative emotion in the form of activating the fight or flight response to perceived threats that are not life-threatening.[2] Trauma is defined as an experience involving perceived or actual threat of violence or death, witnessing or learning of a traumatic event happening to a close family member or friend, or repeated exposure to details of the event.[3] Stress and trauma during childhood can lead to the development of several psychiatric conditions, including behavioral conduct disorders, anxiety and depressive disorders, and greater stress reactivity later in life.[4][5] Repetti et al. found that children who grew up in families lacking support and warmth, or who experienced repeated stressful and threatening family encounters, were more vulnerable to mood and anxiety disorders, behavioral conduct disorders, and a general inability to constructively handle stress.[5] Repeated exposure to traumatic and highly stressful events can have many different effects on an individual, these experiences may result in the formation of symptoms or the disorder of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTSD consists of four symptom clusters, including avoidance of reminders of the trauma(s); intrusive thoughts, memories, nightmares or flashbacks of the trauma; negative affect; and hyperarousal, which can manifest as hypervigilance and irritability.[3] While the majority of people who experience trauma will not develop PTSD, approximately 6.8% of the population reports PTSD in their lifetime with a higher rate (15.9%) reported among children and adolescents following exposure to trauma.[6][7][8] Rates of PTSD prevalence for adults who are employed in high stress or high danger contexts range from 0-32%, with 0-8% observed in police officers, 4-17% for combat veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, and 8-32% for emergency first responders.[9][10][11]

Exposure to stressful events/traumas, especially during childhood, has been positively correlated with the development of disorders of depression, such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).[5][12][13][14]. MDD affects 16.6% of the population and is described as a loss of pleasure in activities, increased fatigue, depressed mood or attitude, changes in sleep, feeling guilt or remorse, increased difficulty making decisions, and/or recurring thoughts of death or suicide.[3][7] A large longitudinal study reported odds ratios to quantify the likelihood that a person experiencing a traumatic or stressful event will develop depression.[12] They found that when an individual experienced a stressful life event, he/she had an odds ratio ranging between 2.3 to 25.4 of developing depression, in the month after the stressful event, compared to someone who didn’t experience a stressful event. On average, someone who experienced a stressful event was 5 times more likely to report depression onset in that month, compared with someone who did not experience a stressful event. A review by Mazure examined case control studies to determine if bouts of depression were preceded by stressors and determined that depressed patients were 2.5 times more likely to have experienced a stressful event than none-depressed controls.[13] Thus, cumulative risk exposure and exposure to stressful life events is associated with PTSD symptoms as well as other disorders like depression.

To further examine links between stressful event exposure and psychiatric symptoms, the current study aimed to examine relationships between stressful event exposure and the presence of MDD and PTSD symptoms in a healthy adult sample. The first aim was to examine the relationship between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas and self-report PTSD symptoms associated with those events. We predicted that there would be a positive correlation between experiencing a greater variety of stressful events/traumas and presence of PTSD symptoms. Our second aim was to examine the relationship between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas and self-report depression symptoms related to those events. We predicted that there would be a positive correlation between the number of different types of stressful events/traumas experienced and depression symptoms.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 58 healthy adults, ranging in age from 19 to 43 years (M = 26.71). Fifteen (25.9%) were males and 43 (74.1%) were females. Participants were recruited via the University of Michigan research website. To be involved in the study, participants could not have self-reported any mental health conditions or be taking any medications for psychiatric illness, not have any serious medical conditions or be taking any medications that could affect physiological responsivity or cognition, not be currently pregnant or trying to get pregnant, able to undergo an MRI scan, not be dependent on drugs or alcohol, be right handed, be able to give informed consent, be a fluent English speaker and be between the ages of 18 and 45 years old.

Measures

Life events checklist 5. The life events checklist 5 (LEC- 5) is a seventeen item self-report questionnaire that asks each participant to report if they experienced a variety of different types of traumatic or stressful events throughout their lifetime.[15] There are seventeen different types of events, ranging from sexual assault and murder, to natural disasters or accidents of a variety of sorts. There is also an open response free-form item for events falling under an ‘other’ designation. There are four different ways in which the event could have been experienced, including “happened to you personally,” “you witnessed it happen to someone else,” “you learned about it happening to a close family member or close friend,” and “you were exposed to it as part of your job.” This measure did not allow us to quantify the total number of absolute events experienced, as it specifically assessed the number of different types of events a participant experienced.

Clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is a 30 question semi-structured clinical interview that can be used to make a current (past month) or lifetime diagnosis of PTSD.[15] To use this assessment tool the interviewer asked the participant to identify the most traumatic or stressful experience they experienced based on their responses on the LEC-5. The CAPS-5 consists of a series of questions to assess PTSD symptoms in response to the event. For this study, all participants were asked to answer the questions about their experience during the “worst month” following the event. Each question is scored on a scale from 0 (participant denies experiencing a symptom) to 4 (participant indicates extreme symptoms that are pervasive, unmanageable and overwhelming), with total scores ranging from 0 to 120. We utilized this measure to determine the severity of PTSD symptoms, based on the frequency and intensity of symptoms reported as a sum across all questions, during the worst month following exposure to the stressful event. The entire interview takes between 45-60 minutes to complete.

Beck depression inventory 2. The Beck Depression Inventory 2 (BDI-2) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire.[16] Each question is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 63. This questionnaire measures the severity of a participant’s depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Higher total scores are indicative of endorsement of a larger number of, and/or more intense depressive symptoms. We utilized this measure to determine the severity of current depression symptoms for each participant. This questionnaire takes approximately five minutes to complete.

Procedures

After expressing interest, potential participants completed a telephone screen to determine whether they met eligibility criteria. Participants that met the eligibility criteria were scheduled for a diagnostic interview with a master’s level clinician under supervision of a fully-licensed psychologist. During the interview, the participant completed the BDI-2, LEC-5, and CAPS-5. Upon successful completion of the clinical interview, a subset of participants completed memory tasks during MRI scanning.

Data Analysis. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (Version 24). Mean, standard deviation, and range were reported for each measure (LEC-5, CAPS-5, and BDI-2) to characterize the number of different types of stressful events, PTSD symptom severity during the worst month following the worst event, and current depression symptoms across our sample. Two-tailed Pearson correlations were utilized to examine relationships between the total number of different types of stressful events endorsed on the LEC-5 and both PTSD and depression symptoms. This method of using Pearson correlation to examine the relationship between two continuous variables is consistent with recommendations for statistical analyses in the social sciences.[17] Specifically, to examine the relationship between a number of different types of stressful events experienced and PTSD symptom severity, we conducted a correlation between scores on the LEC-5 and the CAPS-5. To examine the relationship between the total number of different types of stressful events endorsed and depression symptom severity, we conducted a correlation between scores on the LEC-5 and the BDI-2.

Results

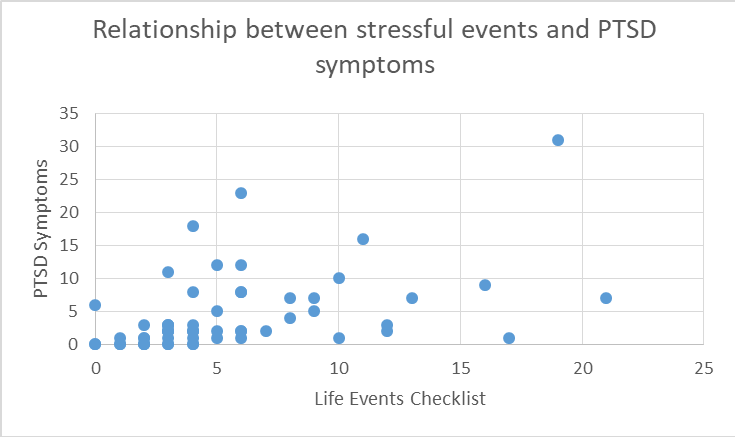

On average, participants reported experiencing multiple stressful events based on the LEC-5 (M = 5.66, SD = 4.65, range = 21). Participants reported low levels of PTSD symptoms (subclinical range) based on the CAPS-5 interview (M = 4.57, SD = 6.0, range = 31), and low levels of depressive symptoms (minimal range) based on the BDI-2 (M = 2.14, SD = 3.39, range = 13). Figure 1 below shows how correlation analysis revealed that there was a positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas endorsed on the LEC-5 and PTSD symptoms during the worst month following the most stressful event on the CAPS-5, r =.455, p = .001.

Figure 1: Relationship between stressful events and PTSD symptoms. Positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas from the LEC-5 and the endorsement of symptoms of PTSD from the CAPS-5 interview.

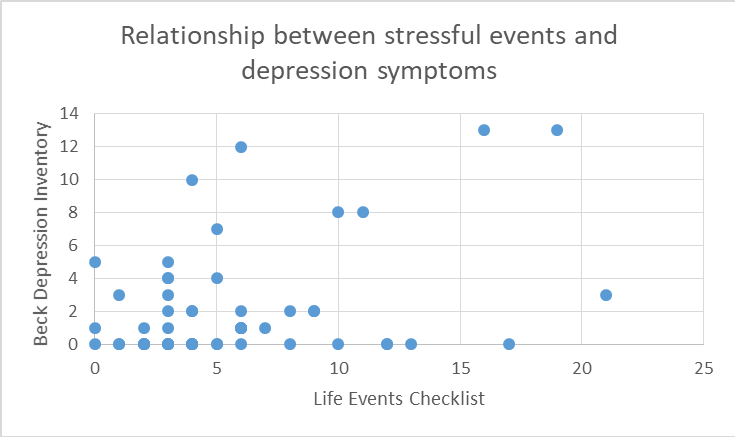

Figure 1: Relationship between stressful events and PTSD symptoms. Positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas from the LEC-5 and the endorsement of symptoms of PTSD from the CAPS-5 interview.Figure 2 below shows how correlation analysis also revealed that there was a positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas endorsed on the LEC-5 and current self-reported depression symptoms on the BDI-2, r = .362, p = .005.

Figure 2: Relationship between stressful events and depression symptoms. Positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas from the LEC-5 and the endorsement of symptoms of depression from the BDI-2.

Figure 2: Relationship between stressful events and depression symptoms. Positive correlation between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas from the LEC-5 and the endorsement of symptoms of depression from the BDI-2.Discussion

The aims of this study were to examine the relationship between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas, current self-reported depression symptoms and PTSD symptoms during the worst month following the most stressful event in a healthy adult sample. Our findings demonstrate that people who experienced a greater variety of different types of traumatic or stressful events endorsed more PTSD and depressive symptoms. We also found that as the number of different types of events/traumas experienced increased, the number of endorsed depressive symptoms increased as well.

Our finding that there was a positive relationship between a greater number of different types of stressful events/traumas experienced and the number of endorsed depressive symptoms is consistent with previous findings reporting that people who experienced stressful events/traumas were more susceptible to developing depression symptoms and depressive disorders.[5][13][14] Our finding that there was a positive relationship between a greater variety of different types of stressful events/traumas experienced and the number of endorsed PTSD symptoms is consistent with previous findings reporting that people who experienced stressful events/traumas were more susceptible to difficulties managing stress and may be more likely to develop PTSD.[5] Our findings are an extension of prior studies, since prior studies focused on clinical populations, while our study examined these patterns in a healthy, nonclinical sample of adults.

Our findings suggest that even in a healthy population, stressful event exposure is associated with depression and PTSD symptoms. This information indicates that healthy people who experience a greater number of different types of stressful/traumatic events may be more at risk for developing depression or PTSD. Knowing that healthy nonclinical individuals are susceptible to depressive and PTSD symptoms following exposure to stressful events could be useful in designing preventative or current stress reduction techniques that assist with not developing a clinical disorder.

There were several limitations to this study. First, our sample was primarily female (74.1%), so the findings reported here may not apply as well to males. Due to a low number of male participants, we were unable to statistically measure gender differences. Future research could look at whether relationships between stressful event exposure and depressive and PTSD symptoms differ between genders. The second limitation was the self-reporting nature of the study. A large portion of our data depended on the ability of participants to accurately report experiences and symptoms. Self-reporting is a good source of information because it allows for the assessment of internal experiences that are not readily observable. However, response or sampling bias, difficulty with being honest, difficulties remembering past experiences, lack of introspective ability, and misinterpretation of the questions may result in inaccurate representations of symptoms and events.[18]

Another limitation is the inability to establish causality due to the design of the study. While our data suggest that a relationship exists between stressful life events and depression and PTSD symptoms, we cannot establish that stressful life events cause depression or PTSD symptoms. Future research could adopt designs to more effectively assess causal influences between stressful event exposure, PTSD, and depression among healthy, nonclinical populations. Instead of looking at how experiencing a variety of different events affects people, future research could look at what the effects are from experiencing specific events or repeated specific events. Future research could also look at the link between the experience of a variety of different stressful events/traumas and the comorbid symptoms of depression and PTSD. Future research could also look at whether marital status or other social factors are associated with symptoms of depression or PTSD following stress exposure.

References

- *

To whom correspondence should be addressed: eduval@umich.edu

Suri, D., & Vaidya, V. A. (2015). The Adaptive and Maladaptive Continuum of Stress Responses – a Hippocampal Perspective. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 26(4). doi:10.1515/revneuro-2014-0083

Turner, M., & Jones, M. (2018). Arousal Control in Sport. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.155

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Evans, G. W., Swain, J. E., King, A. P., Wang, X., Javanbakht, A., Ho, S. S., . . . Liberzon, I. (2015). Childhood Cumulative Risk Exposure and Adult Amygdala Volume and Function. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 94(6), 535-543. doi:10.1002/jnr.23681

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330-366. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.230

Breslau, N. (2002). Epidemiologic Studies of Trauma, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and other Psychiatric Disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(10), 923-929. doi:10.1177/070674370204701003

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., Wesel, F. V., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(05), 335-340. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227

Berger, W., Coutinho, E. S., Figueira, I., Marques-Portella, C., Luz, M. P., Neylan, T. C., . . .Mendlowicz, M. V. (2012). Rescuers at risk: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1001–1011. 10.1007/s00127-011-0408-2

Richardson, L. K., Frueh, B. C., & Acierno, R. (2010). Prevalence Estimates of Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Critical Review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(1), 4-19. doi:10.3109/00048670903393597

Lanza, A., Roysircar, G., & Rodgers, S. (2018). First responder mental healthcare: Evidence-based prevention, postvention, and treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(3), 193-204. doi:10.1037/pro0000192

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M., & Prescott, C. A. (1999). Causal Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and the Onset of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 837-841. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.6.837

Mazure, C. M. (1998). Life Stressors as Risk Factors in Depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 291-313. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00151.x

Shapero, B. G., Black, S. K., Liu, R. T., Klugman, J., Bender, R. E., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2013). Stressful Life Events and Depression Symptoms: The Effect of Childhood Emotional Abuse on Stress Reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 209-223. doi:10.1002/jclp.22011

Weathers, F.W., Blake, D.D., Schnurr, P.P., Kaloupek, D.G., Marx, B.P., & Keane, T.M. (2013). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). Interview available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Field, A.P. (2005). Discovering Statistics using SPSS for Windows. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

Salters-Pedneault, K., & Gans, S. (2018, November 05). The Use of Self-Report Data in Psychology. Retrieved January 26, 2019, from https://www.verywellmind.com/definition-of-self-report-425267