Good for Business: Applying the ACRL Framework Threshold Concepts to Teach a Learner-Centered Business Research Course

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article discusses a librarian-designed and facilitated credit-bearing course, which utilizes the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy Threshold Concepts and transforms from Bloom’s Taxonomy to a learner-centered course redesign with Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning. Assessment results reveal a panel of data over the 2015-2016 academic year offering perspectives at the beginning and end of each semester and over the course of the entire academic year’s trajectory of learning. In an effort to imbue more affective learning outcomes, and based on answers received from fall assessments, the author altered the spring assessment to query student confidence levels and the value of the library. This article provides lesson plans that highlight each of the six Information Literacy Threshold Concepts in a business context and offers a trajectory toward significant and lifelong learning.

Keywords: Assessment; Information Literacy Instruction; Threshold Concepts; ACRL Framework; Learner-Centered; Instruction Design; Business Research; Fink’s Taxonomy; Bloom’s Taxonomy

Introduction

Since the official release of the Association of College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Framework Threshold Concepts for Information Literacy for Higher Education in February 2015, the professional literature lacks discipline-specific instruction design or lesson plan examples. Gibson and Jacobson (2014), co-Chairs of the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education Task Force asked in an editorial for Colleges and Research Libraries: “Are the threshold concepts in the framework applicable to all disciplines?” I argue that they indeed are applicable to all disciplines, especially business. I will illustrate how I have adopted them in an accelerated credit-bearing business research course for business honors students over the 2015-2016 academic year. I will demonstrate how the course was designed to imbue library instruction with significant learning by sharing the assessment results as gathered during both semesters of the 2015-2016 academic year.

While much of the professional information literacy literature has been connected to Bloom’s Taxonomy, as of this writing, there has not yet been any published literature that has made the connections between the Threshold Concepts in the ACRL Framework and Fink’s Taxonomy for Significant Learning, such as those outlined in this article. As the business subject librarian, I created and taught a business research course for two semesters, in which students were administered a pre- and post-assessment questionnaire. As evidenced by the assessment described, the Threshold Concepts in the Framework worked well in the business discipline. Students became oriented with library and online resources and skillsets needed to execute search tasks. Students demonstrated the ability to utilize the foundational skillset they learned in this course in other classes and in the field. From initial inquiry and through exploration, the value of seeking information of contextual quality has offered transformative learning experiences for students to become more responsible leaders and participants in the business community.

Literature Review

The role of the academic librarian has expanded beyond bibliographic instruction and into the realm of pedagogical praxis. Librarians, especially subject specialists, are expanding their professional identity to the role of instructional designers and professors. Walter (2008) examined the increasing amount of job posts for academic librarians that require experience in instruction. In Walter’s examination of the teaching identity of librarians, the author cites the challenges of librarians and administrators to integrate library services into the broader university mission while keeping up with the “changes in scholarly communication, advances in information technology, and new modes for professional staffing of academic libraries” (Walter, 2008, p. 51). Librarians are positioned to instruct the information content that other teaching faculty are not fully trained to do.

Library instruction training is often available as an elective course offered in Master of Library and Information Science programs. Thus, most instruction librarians learn how to teach while on the job. Instruction librarians learn to: “organize and structure ideas logically; deliver lecture, vary pace and tone, use eye contact, use appropriate gestures; provide clear, logical instructions; determine a reasonable amount and level of information to be presented in a lesson plan; verbalize a search strategy; and understand student assignments and the role of the library in completing those assignments” (Walter, 2008, p. 57-58). Walter found, through his qualitative research on instruction librarians’ professional identity that “learning theory, instructional design, pedagogical skills, and an understanding of faculty culture” are of greatest importance (Walter, 2008, p. 58).

Since the release of ACRL’s Framework Threshold Concepts for Information Literacy, many instruction librarians have created toolkits and shared pedagogical advice on professional e-mail discussion lists and publications. The biggest shift in library instruction from the ACRL Standards to the new Framework is in the way instruction librarians are challenged to think about why we teach what we teach. We are no longer asked to have students memorize how to recreate a canned search but rather to think about why they make certain choices in their search, and to expose them to the overall information ecosystem. The framework is more centered on the learners becoming empowered to make decisions, no matter what database or website they encounter. Students are empowered by their responsibility to be responsive and productive contributors to the information landscape. The Framework “requires us to introduce concepts that will hold their attention, change their viewpoint and provide revelatory ‘aha’ moments” (Gibson & Jacobson, 2014). The Threshold Concepts bring students toward mastery as they are transformed from lay information consumers into content creators.

Instructional design models can be scaled for one-shot instruction sessions as well as for credit-bearing courses to teach Threshold Concepts. The BEAM model offers analysis on sources that as Christiansen (2015) discusses aligns well with the Framework. BEAM offers structure for students to analyze the Background source, Exhibit source, Argument source, and Method source in their own writing. Christiansen states that “BEAM encourages instructors to change language in order to change student behavior” (2015). Christiansen also discusses the use of ARCS Model in library instruction to teach the Framework. Drawing from motivational design, the ARCS Model encourages instructors to emphasize Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction as measures of a successful instruction session. Using such instructional design models can offer students a deeper and more concrete connection with the content they are learning so they can better absorb and retain the new material.

The Framework expands the possibilities of pedagogical praxis to design more learner-centered reflective instruction sessions. Foasberg (2015) highlights the aspects of the Framework to be more community-oriented and civically engaging, especially as the instruction sessions focus less on the tools being used to consume information and more on the patron as a member of the information ecosystem. It is refreshing that while students are learning about their discipline, they are also encouraged to exercise skepticism of sources, authority, and institutional hierarchy in information distribution. Only then can students understand the social context of the field and culture of the discipline.

Much of the literature applauds the Framework for focusing on students as participants in learning and as creators of information. Students should be considered contributors to their discipline, albeit on another part of the same path as their professors and other experts in the field. Burgess (2015) states that the Framework, being still so new and unfamiliar, allows instructors to be vulnerable—as are students when learning something unfamiliar or troublesome. Burgess optimistically imparts that all are lifelong learners who are on different points of the same path. The Framework provides fodder to “create transformative sessions designed to engage troublesome knowledge, which will result in an integrative and irreversible learning experience for students” (Burgess, 2015, p. 3). Library instructors ought to show students just how messy and non-linear research actually is, and that the only thing a researcher has control over throughout the research process is his or her own behavior. Resilience, curiosity, and persistence are critical traits to successfully accomplish research.

Instructors are encouraged to ask students questions to facilitate discussion, to develop research questions, and to seek multiple perspectives. Bond (2016) shares how inquiry-based instruction drives student learning. Bond describes giving students more agency in their education by having them lead discussions by developing topics and generating questions from course material. Because students were responsible for their own learning and the learning of their fellow classmates, they were motivated to contribute to the creation of that content. As a result of leading discussions and contributing to blog posts, Bond explains: “throughout the course, students developed several metaliteracy skills: leadership, collaboration, speaking and presentation, planning, research and a variety of digital media skills” (p. 5).

Much of the Framework literature highlights the underlying objectives of metaliteracy and metacognition informed through the transformative conceptual process. The pedagogical practices of self-regulation and self-reflection offer students the opportunity to independently examine why they made certain choices in navigating the research process. Self-questioning prompts the student to look at cognitive processes, behavioral actions, and their consequences. By cultivating self-understanding, students learn how they learn, and what to do to improve in the process. As Houtman (2015) states, “what the concept of self-regulated learning allows us to do is pull together all the different elements that put students at the center of their own learning” (p. 8).

Dahlen (2012) explored how adult education can be expanded into information literacy instruction. Since Threshold Concepts force students to crossover into new realms, students are afforded support as they progress through each developmental stage. Dahlen found four major themes in adult education that can be adapted in learner-centered library instruction. Adults seek opportunities for self-motivation, are goal driven, want to connect new knowledge to life experience, and may offer a body of prior knowledge which differs from that of their classmates. Dahlen cautions instructors to “be conscious of the choices that they make in the classroom and the educational justifications of each choice” (Dahlen, 2015, p. 7). The author stresses the importance of clear and transparent learning goals and objectives so that students have the opportunity to take responsibility for their learning.

Methodology

Over the course of the 2015-2016 academic year, in the fall and spring semesters, a pre- and post-assessment questionnaire was administered to students enrolled in the business research methods course. All pre-assessment questionnaires were administered via Survey Monkey before the first class meeting and communicated through the class e-mail list from the course management system. The post-assessment questionnaire was administered after the last class meeting when all final assignments had been handed in. Students knew that the assessments were voluntary, anonymous, and were unconnected to their course grade

Limitations of this study

The data indicate a correlation between student achievement and this curriculum, rather than causation. Additionally, because the questionnaire responses were anonymous, tracking students within the same semester was impossible in order to prove an individual’s growth or academic improvement. Student outcomes are described as a percentage change because the respondents may differ from each time the questionnaire was administered. While the student learning outcomes look promising, future research is needed.

Results and Discussion

Assessment results reveal a panel of data over the 2015-2016 academic year offering perspectives at the beginning and end of each semester and over the course of the entire academic year’s trajectory of learning. I used each semester’s pre-assessment to measure learning over the course of the semester and to better understand what students already knew at the beginning of the class session. An example question: “When doing business research, you use: (A) A search engine like Google; (B) Library databases; (C) Business press or business blog; (D) Government documents or government website; or (E) Other (Please specify)”. Another example question used to gauge what students know about the business field is: “What are the names of some professional associations that publish in your major field (i.e., accounting, economics, finance, management, marketing, information systems, etc.)?”

Students were also asked why they enrolled in the research course and what they hoped to learn. The pre-assessment data informed planning of the course.

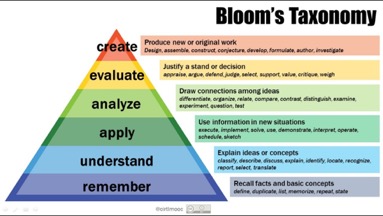

To best explain the results, I will use Bloom’s taxonomy, which consists of a pyramid of six tiers of cognitive domain. The base of the pyramid is considered the lowest order and gradually culminates in the highest order of learning at the tip of the pyramid. The lowest tier of the pyramid is remembering, built upon by understanding, followed by application, then analysis, then evaluation and finally creation (See Figure 1).

Since the class is listed as a sophomore (200) level course valued at one-credit unit, and graded on a credit/no-credit basis, there were limits on how much students could be expected to produce. The purpose for this course was simply to expose students to the resources they may want to consider for future research; be able to remember the resources at the appropriate time; understand the capacity of each source; and to be empowered to conduct independent research by their senior year capstone project. These objectives were determined appropriate, based on prior knowledge of what students have been exposed to in their business education.

The course embodies all of Bloom’s taxonomy components, but it intentionally focuses on the lower-mid portion of the model by targeting understanding and application. The purpose of the course is to prepare students for the deeper critical thinking and develop evaluation skills needed for higher-level work.

Most students enrolled were seniors, followed by the next largest enrolled group, of juniors. Sophomores comprised 8% of enrolled students in the fall class and increased to 23% of enrolled students in the spring class (see Table 1). Regardless of class standing, all the students had little prior knowledge of the content and started out with a minimal skillset to accomplish the analysis and evaluation I attempted to extract from their self-reflections and elevate in the assignments.

| Fall 2015 | Spring 2016 | |

|---|---|---|

| Freshman | 0% | 7.69% |

| Sophomore | 8.33% | 23.08% |

| Junior | 30.56% | 50% |

| Senior | 61.11% | 19.23% |

Fall 2015 assessment results

While there were 36 students enrolled in the class who also took the pre-assessment questionnaire, only 24 of those students also took the post-assessment.

In the pre-assessment, 81% of respondents indicated they enrolled in the class because they desired to learn a skill they could apply to their academic and professional work. Nineteen percent of respondents indicated they sought to gain an understanding and awareness of resources within the field. When asked in the post-assessment what they actually learned in the class, 30% of participants named concepts they understood, and 70% of participants were able to name skills they had gained and could now apply in their academic and professional work.

One student even commented on being able to analyze and think more critically about the resources. (See Table 2.)

| Pre-Assessment | Post-Assessment | |

|---|---|---|

| Learn to apply a new skill | 81% desire to learn new skill | 70% identify new skills |

| Gain new understanding of key information/research concepts | 19% desire to understand key information concepts | 30% identify key concepts understood |

One goal of the course was to teach authoritative sources in the business discipline by having students research professional associations that publish work in the field. In the pre-assessment questionnaire, when asked to name a professional association in their field, students were only able to name an average of less than one association per student. In the post-assessment, each student named an average of almost two relevant professional associations.

When students were asked what remained confusing to them, some indicated confusion about which database to use and when to use it. In response, I created a concept map using the open source software, Spicy Nodes, to illustrate recommended databases for the various fields of business research (see http://goo.gl/8MLSAF)

The fall assessment questionnaires also asked students where they look for information and what types of sources they use. There was a decrease of 16.67 percentage points in using Google (from 91.67% in the pre-assessment questionnaire to 75% in post- assessment questionnaire) and an increase of 29.16 percentage points in using government websites or documents (from 41.67% to 70.83%) over the duration of the course. There was an 18.81 percentage point increase in utilizing images or maps (from 22.86% to 41.67%) from the beginning of the semester. There was similarly, a 17.86 percentage point increase in utilizing interviews (from 57.14% to 75%) for research as well as a 14.17 percentage point increase (from 40% to 54.17%) in using speeches in research over the course. Student also specified using trade journals and archives after completing the course. There was no significant percentage change in students using library databases, which remained steady at 75%. One possible meaning to this is students are already being exposed to library databases, but not the other resources. See Table 3 for the percentage point change of sources used by students for business research over the course.

| Selected sources | Fall 2015 Pre-Assessment | Fall 2015 Post-Assessment | Percentage point change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 91.67% | 75% | -16.67 pp | |

| Library Databases | 75% | 75% | 0 pp |

| Government websites | 41.67% | 70.83% | +29.16 pp |

| Images/Maps | 22.86% | 41.67% | +18.81 pp |

| Interviews | 57.14% | 75% | +17.86 pp |

| Speeches | 40% | 54.17% | +14.17 pp |

Spring 2016 assessment results

Based on the answers received from the fall assessments, the author changed the questionnaire to focus more heavily in the post-assessment questionnaire on confidence level and library’s value. For example, the spring questionnaires did inquire about what sources students currently used before the course, but was more interested in students’ confidence levels in using a variety of sources after the course rather than if they use specific types of sources or resources such as search engines, government websites, or library databases themselves. Therefore, there is no similar chart like Table 2 for spring 2016. Instead, there were new qualitative questions that specifically asked about students’ value for the library and if their values have changed after taking this course. Those results will be discussed later in this section.

The pre-assessment questionnaire had 26 respondents while the post-assessment questionnaire had 15 respondents. When asked why students enrolled in the research methods class in the pre-assessment, half the respondents indicated a desire to understand the resources, while the other half explicitly indicated a desire to gain a skill to apply to their academic or professional career. However, when explicitly asked if they learned what they hoped to in the post-assessment questionnaire, two thirds of respondents indicated they gained at least an understanding of research and resources, while one third indicated an increased skillset. Moreover, when explicitly asked what they learned in the course, 71 % of respondents named skills they gained and have already applied to other coursework or professional work and 29% of respondents named what they now understand about research. (See Table 4.)

In the post-assessment, there were some students who indicated continuing a confusion about how to use government websites like the Census Bureau. In response to this, the author has hosted the local Census Bureau Data Dissemination Specialist in leading workshops for finding and using census data specifically for business and economic data. The workshop is open to all faculty and students.

Again students were asked to name professional associations that publish in their major field of study. In the pre-assessment questionnaire, when asked to name a professional association in their field, students were only able to name an average of less than one association per student. In the post assessment, however, each student was able to name an average of almost two professional associations that publish in their specific field.

Differing from the fall semester’s post-assessment questionnaire, the spring post assessment questionnaire asked students about their confidence level and value of the library. One-third of respondents felt fairly confident in their research abilities as a result of this class, while as many as two-thirds felt very confident in their abilities to conduct business research. When asked about the library’s value, each respondent indicated an increased awareness and appreciation for what the library offers. While all comments were positive, one response indicated a discomfort with using archives because they had not previously been exposed to them. As with each new exposure, students were encouraged to independently visit the library’s Special Collections and Archives department after the in-class demonstration and presentation.

| Pre-Assessment | Post-Assessment | |

|---|---|---|

| Learn to apply a new skill | 50% desire to learn new skill | 71% identified new skills |

| Gain new understanding of key information/research concepts | 50% desire to understand key concepts | 29% identified key concepts understood |

Academic year assessment results

Both fall and spring semester assessment results indicated that most students (70% for fall and 71% for spring) learned an applied skill they could execute, and all students at least gained an understanding and increased awareness of business resources available through the library and online.

One student remarked, “I finally learned how to do proper research! This class taught me how to search for more credible research using [library] databases. I even used the knowledge that I learned in this class to find research for a big marketing paper that I had to do.” Another student commented, “I learned more than I expected to. There were a lot of resources available that I never thought to use, and now can’t imagine not using them. I’ve already used the Census information for another class this semester.”

Furthermore, when asked if he or she had learned something from the course, a graduating senior commented retrospectively, “Yes, I wish that I had the opportunity to take this class in my freshman or sophomore year, it would have helped me a lot in my senior year projects, particularly the business honors mentorship and the Business Capstone class”.

All student’s comments have been positive. Students have recognized the skills gained in this course ought to be available to all business students at least in time for junior and senior level work. Students benefit from this type of an instructional model wherein they can effectively rise toward the analysis, evaluation and creative abilities expected to achieve and demonstrate upon completion of major curriculum.

Instructional design

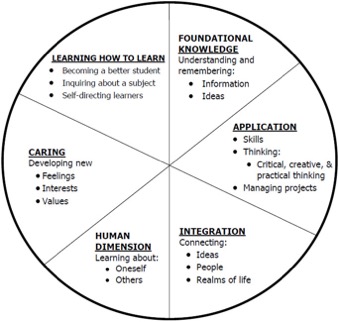

In the spring 2016 semester, I had the opportunity to participate in a faculty learning community which focused on redesigning courses to become more learner-centered. In this community, there was a literature study on effective pedagogy for reflective and significant learning including the work of L.Dee Fink, especially the Taxonomy of Significant Learning (See Figure 2). This work directly influenced the course redesigned assessments and activities.

Fink’s taxonomy differs from that of Bloom’s in that learning is represented cyclically rather than hierarchically. Where Bloom’s taxonomy separates cognitive and affective domains, Fink incorporates both cognitive and affective together to impart transference between domains and cross pollinates among taxons. (See Figure 2.)

For learning to be significant, there must be elements of humanity where students have opportunities to develop new values. Fink (2013) said, “For learning to occur, there has to be some kind of change in the learner. No change, no learning. Significant learning requires that there be some kind of lasting change that is important in terms of the learner’s life” (p. 34).

The cyclical nature of Fink’s taxonomy infuses cognitive learning with affective learning simultaneously, whereas Bloom’s taxonomy separates these stages of learning. While gaining foundational knowledge and applying new skills, learners are learning how they learn best to integrate their learning in to their human experience and value set. Fink’s “caring” and “human dimension” taxons promote new possibilities for learning ethics, communication skills, and leadership and interpersonal skills which build character and the ability to adapt to change One purpose of this course was to increase the library’s value. Fink’s taxonomy of Significant Learning has become the pedagogical undercurrent for the redesigned business course utilizing the ACRL Framework Threshold Concepts. The new learning outcomes for this course can be adapted for any discipline.

While redesigning the instruction for this course, I serendipitously became aware of the six of Fink’s taxons and six Threshold Concepts in the Framework, which I found were very well suited for each other. While much of the professional information literacy literature has connected Bloom’s taxonomy to the ACRL Standards, as of this writing, there has not been any published literature that has made such connections between the ACRL Framework Threshold Concepts and Fink’s Taxonomy for Significant Learning. The following pairings detail the lesson plans for the threshold concepts and their corresponding link to Fink.

Threshold concepts learning outcomes for significant learning

Authority is Contextual – Foundational Knowledge

- I understand... my responsibility to seek out authoritative information.

- I can... determine what makes an authoritative source in my discipline.

- I value... important ideas and facts in my discipline.

Searching as Strategic Exploration– Application

- I understand... information systems are organized.

- I can... determine when sufficient information has been gathered.

- I value... developing skills to seek and locate useful information.

Information Creation is a Process – Integration

- I understand... how individuals create and disseminate information in my field.

- I can... identify different types of sources.

- I value... being connected to the manifestation of ideas.

Research as Inquiry – Learning How to Learn

- I understand... how to frame useful questions in academic research.

- I can... combine findings to identify questions for future research.

- I value... my persistence and flexibility in transferring knowledge.

Information has Value – Caring

- I understand... implications of intellectual property and open access in my work.

- I can... make informed choices when sharing information.

- I value... reputable resources as contributing to my academic success.

Scholarship as Conversation – Human Dimension

- I understand... all information sources display a perspective.

- I can... identify influential works which demonstrate contributions to my field.

- I value... my ability to critically reflect & sensitively respond in the conversation.

Lesson plans for teaching the ACRL framework threshold concepts

Authority is constructed and contextual. To give context to constructed and contextual authority, students are prompted to reflect on someone who has authority in their own life. They are given the opportunity to share with a partner about that person. The instructor explains to students that, like that person in their life, there are authoritative bodies in their field that govern and produce standards for operating. These entities are often associations that have members who are a part of that profession. These associations publish a variety of research that construct and give context to the field. Students are prompted to learn about the major publishing professional associations in their field by going to resources in the library and online.

- Link to Fink: Knowledge of the standards in practice and regulations in the field are Foundational Knowledge.

Searching as strategic exploration. The class is divided into working groups of approximately seven students per group. Students are given the opportunity to become entrepreneurs to collectively plan a business. The group develops a search strategy. Each group member selects type of source. Each student takes a screen shot of source selected and posts it to the group’s Padlet page. Students must justify their choice and teach the search strategy they used to locate the source to their working group.

- Link to Fink: Strategic and exploratory searching is refined through the practical application of critical and creative thinking.

Information creation as a process. In this lesson, students are learning about the research cycle and primary sources. Students are exposed, often for the first time to the library’s special collections and archives. In collaboration with the library’s Head of Special Collections and Archives, the students are given a hands-on demonstration where they can explore regional labor union documents, rare books and hand-written artifacts. After the in-person session, students are encouraged to examine current primary source data about a chosen company by searching social media. Students are asked to consider what information they are not seeing and for whom the information is intended.

- Link to Fink: By integrating primary sources, from archival and contemporary sources, students have a foundation for the process of information creation.

Research as inquiry. Discussion is prompted by asking students what research they already do, although we may not call it by that name. Students are then prompted to teach something they already know well to a partner. Their partner asks them a question about it. The instructor asks students to reflect on where they go for information if they want to know more. Students learn that the perfect source may not exist, but multiple sources need to be consulted and multiple questions may need to be asked to get the best answers. The students are reminded that most important learning dispositions are curiosity, persistence, and flexibility.

- Link to Fink: Students learn how to learn by asking curious questions.

Information has value. Students are prompted to reflect and discuss as a class: how we get information; what information should look like; and what information should be able to do. Students are also given the opportunity share a time they needed information and how having that information added value to their personal experience. The instructor reminds the students of their privilege in accessing information through the library and online. The instructor begins to explain implications of intellectual property, copyright, open access and fair use in the business profession.

- Link to Fink: By reflecting on their value of knowledge, students realize they care about accessing reliable information to make better decisions.

Scholarship as conversation. The instructor explains the importance of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and separately, the U.S. Census Bureau in regards to business information and implications for further research. Students are tasked to choose a U.S. public company and find its annual report and industry statistics using these SEC and Census websites. Students are also asked to examine the content of an annual report by comparing what is popular in business news media.

- Link to Fink: By learning about human dimensions, which foster the business community, students can understand how information can contribute to sustainable environments, organizations, or economies.

It is important to note that the Threshold Concepts have no prescribed order for instruction. In fact, the way I have presented them here were not the order in which they were taught in this course. These are only in cyclical order to the image of Fink’s Taxonomy shown in Figure 2. Instructors are encouraged to reorder as appropriate.

There were various types of assessments in this course. Aside from the formative assessment data, there were also summative assessments and what Nilson (2010) calls “forward looking assessment.” The summative assessments included tutorials embedded in the course management system and an annotated bibliography and literature review that was due by the end of the semester from each student. The forward-looking assessment offered a low-stakes assignment, on which immediate instructor feedback is provided. Students were assigned a project prospectus to guide their research toward what would become the annotated bibliography and literature review, which ultimately determined satisfactory completion of the course.

Actions

As I work on developing more self-reflective and self-regulated learning, I aim to incorporate additional opportunities for students to post in an online forum, to give more feedback, and to monitor progress throughout the research process. As Bond (2016) was able to successfully employ students to maintain blogs because they had a vested interest in being accountable to their fellow classmates, I will explore such motivations for my students. Students will be encouraged to write about their “aha” moments or even the muddiest points during exploration along their research pathways.

However, I am still learning how to encourage students to participate in the course discussion and independent activities. If I do not assign a grade to a task, only those students who are intrinsically motivated will do the work while the remaining students will opt out of participation. I am seeking ways to tap into the cultural and community values of business students. I want students to be self-motivated because they inherently care about their own learning and will, therefore, willfully participate in class discussions both in-person and online.

Conclusions

Since the publication of the ACRL Framework, librarians are better equipped to teach essential skills for lifelong learning that will sustain beyond the college experience. Through learning the Threshold Concepts, students are better equipped with skills to become more proficient in information related activities in their field as they continue in their academic and professional careers.

The results of this qualitative study provide insights into how the Threshold Concepts bode well in a credit-bearing information literacy instruction model for business students. Additional research is necessary to make conclusive statements, but things look promising for the Threshold Concepts in the Framework to work well in the business discipline. Through this business research course, students became oriented with library and online resources and skillsets they will need to execute search tasks. Students will be able to utilize the foundational skillset they learned in other classes and in the field. From initial inquiry and through exploration, the value of seeking information of contextual quality has transformed these students to be more responsible leaders and community participants.

Comparable to their peers, students from this course have the research skills to access and utilize to the resources to get a head start from anywhere on their own knowledge path. Anecdotally, a former student told me that his colleagues, who were not students of this course, asked him where he learned how to do the research needed for their senior capstone project. He told them they should have taken this business research course!

References

- Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Blumberg, P. (2009). Developing learner-centered teaching: a practical guide for faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Barkley, E. (2010). Student engagement techniques: a handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bloom, B.S, et, al. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Co., Inc.

- Bond, P. (2016). Addressing information literacy through student-centered learning. Education for Information, 32, 3-9. DOI 10.3233/EFI-150961.

- Bravender, P., McClure, H. A., & Schaub, G. (2015). Teaching information literacy threshold concepts: lesson plans for librarians. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

- Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (1998). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education. Buckingham; Philadelphia, PA: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Burgess, C. (2015). Teaching students, not standards: yhe new ACRL information literacy framework and threshold crossings for instructors. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(1).

- Christensen, M.K. (2015). Designing one-shot sessions around threshold concepts. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 20(4), 97-104. DOI: 10.1080/10875301.2015.1109573

- Dahlen, S. (2012). Seeing college students as adults: Learner-centered strategies for information literacy instruction. Endnotes: The Journal of the New Members Roundtable, 3(1).

- Fink, L. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Foasberg, N.M. (2015). From standards to frameworks for IL: How the ACRL framework addresses critiques of the standards. Libraries and the Academy, 15(4), 699-717.

- "Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education", American Library Association, February 9, 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

- Gibson, C., & Jacobson, T. (2014). Informing and extending the draft ACRL information literacy framework for higher education: an overview and avenues for research. College & ResearchLibraries, 75(3), 250-254.

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2011). Causality orientations moderate the undermining effect of rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 485-489. DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.10.010

- Houtman, E. (2015). Mind-blowing: fostering self-regulated learning in information literacy instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 9(1), 6-18.

- Huba, M. & Freed, J. (2000). Learner-centered assessment on college campuses: shifting the focus from teaching to learning. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Nilson, L.B. (2010). Teaching at its best: a research based resource for college instructors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- O’Neill, G. & Murphy, F. (2010). Assessment: Guide to taxonomies of learning. University College of D Dublin Teaching and Learning Resources. Retrieved from: http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtla0034.pdf

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Self‐regulation and the problem of human autonomy: does psychology need choice, self‐determination, and will? Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1557-1586.

- Walter, S. (2008). Librarians as teachers: a qualitative inquiry into professional identity. College & Research Libraries, 69(1), 51-71.

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-centered teaching: five key changes to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Appendix: Business Research Methods Survey Questions

Fall 2015 Pre-Assessment Questionnaire

- Please tell me your class level

- Please let me know why you enrolled in this Research Methods course

- When doing business research, you use:

- A search engine like Google

- Library databases

- Business press or business blog

- Government documents or government website

- Other (Please specify)

- Other than books and journals, what other types of information are you familiar with or would use for business research?

- Dissertations/ theses

- Magazines

- Newspapers

- Websites

- Manuscripts

- Images/ pictures/ maps

- Conference proceedings

- Interviews

- Television/ radio

- Videos/ movies

- Speeches

- None of the above

- Other

- Describe your process of finding a business periodical using library resources.

- What associations and organizations are major publishing bodies in your specific field (i.e., accounting, economics, management, etc.)?

Fall 2015 Post-Assessment Questionnaire

- Please tell me your class level

- Please let me know why you enrolled in this Research Methods course

- When doing business research, you use:

- A search engine like Google

- Library databases

- Business press or business blog

- Government documents or government website

- Other (Please specify)

- Other than books and journals, what other types of information are you familiar with or would use for business research?

- Dissertations/ theses

- Magazines

- Newspapers

- Websites

- Manuscripts

- Images/ pictures/ maps

- Conference proceedings

- Interviews

- Television/ radio

- Videos/ movies

- Speeches

- None of the above

- Other

- Describe your process of finding a business periodical using library resources.

- What associations and organizations are major publishing bodies in your specific field (i.e., accounting, economics, management, etc.)?

- What top three things did you learn from this class?

- Of the content presented in class, what areas remain unclear?

Spring 2016 Pre-Assessment Questionnaire

- Please tell me your class level.

- Please let me know why you enrolled in this Research Methods course.

- When doing business research, you use:

- A search engine like Google

- Library databases

- Business press or business blog

- Government documents or government website

- Other (Please specify)

- What are the names of some professional associations that publish in your major field (i.e., accounting, economics, finance, management, marketing, information systems, etc.)?

- How do you feel about the library?

Spring 2016 Post-Assessment Questionnaire

- Please tell me your class level

- Based on your reasons for enrolling in this course, did you learn what you’d hoped to learn?

- Please describe your confidence in using library resources and business resources as a result of this course.

- What are the names of some professional associations that publish in your major field (i.e., accounting, economics, finance, management, marketing, information systems, etc.)?

- How do you feel about the library? Has your value of libraries changed as a result of this course?

- What are the top three things you learned in this class?

- What still remains unclear or confusing?

Charissa Odelia Jefferson is the Business and Data Librarian at California State University, Northridge, [email protected].