The Role of Business Librarians in Teaching Data Literacy

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Keywords: Data literacy, Statistical literacy, Business school undergraduates, Business Schools, Business Librarians

The amount of data is projected to grow at a rate that doubles every two years until 2020 (IDC, EMC, 2014). With their routine participation in data creation through Facebook likes, online shopping, and political polling, even non-numerically inclined people are more aware of data.

In this era of big data, the need for data literacy is growing (Lohr, 2012). Data literacy is “understanding what data mean, including how to read charts appropriately, draw correct conclusions from data and recognize when data are being used in misleading or inappropriate ways” (Carlson et al., 2011). The emphasis in this definition is on data consumption and critical assessment (Koltay, 2015).

The rapid growth of data about customers, their behaviors, what they say, and where they shop, has created a demand in business for data scientists and people with deeply analytical skills (i.e. statisticians) (Davenport & Patil, 2012). There is also a need for data savvy managers, people who understand how to use data, who can ask critical questions, propose new studies, and draw insights from data (Harris, 2012). A 2011 study by the McKinsey Global Institute suggested that by 2018, there will be hiring gap of 1.5 million data-literate managers and analysts (Manyika, et al, 2011).

The need for data-literate employees has been confirmed by my own experience in the corporate world. Firsthand examples include employees using mismatched data to make forecasts for product sales, using insufficient data for price changes in foreign countries, and modelling technology adoption with outdated information that fails to account for today’s consumers’ buying habits. Businesses need data -literate employees for everyday business decision making.

Business librarians regularly teach information literacy to business-school students (Cooney, 2005) (Detlor, et al., 2011) and there are librarians teaching data literacy (Hunt, 2004) to non-business majors. However, there is little evidence of business (or other) librarians teaching data literacy to business school students.

Business librarians can step up and fill this gap. Although data literacy may sound new and different, many of the skills relate to scholarly research. Data literacy is more about words than numbers, more about evidence than about formulas (Schield, 2004). Data literacy refers to a small part of the whole data lifecycle, which ranges from data creation through data storage.

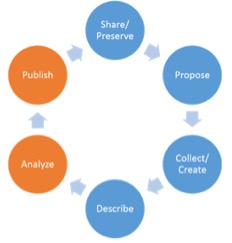

As depicted by the University of California San Diego Library in its data management lifecycle model (see Figure 1), data literacy relates to the “Analyze” and “Publish” phases that involve secondary research (though may also question primary research), critically thinking about authority and appropriately using found data (much like a found quote or argument).

Models of Data Literacy Instruction

Course-integrated instruction

For the undergraduate business major, data literacy could be addressed in any or all of the following courses outlined in the Table 1. While this table is not exhaustive, it is meant to illustrate the potential integration of data literacy skill practice (Prado & Marzal, 2013) into the standard business curriculum. This requires working with faculty to make sure one or more library information and data workshops are part of the course instruction, whether during course time, online, or in an additional sessions.

For example, in a marketing class, students must often understand the target market. In order to ascertain potential customers, they must define a certain demographic. In one Integrated Marketing class at the Eastern Michigan University (EMU) College of Business, the professor created an assignment to target the millennial population who is interested in buying cars. In addition to finding out what kinds of car features millennials prefer—environmental, musical, network compatibility, leasing versus owning, for example. Students must also assess how many millennials are shopping for cars each year, consider millennial salaries and their use of competing offerings like Uber. Students also must understand how targeted marketing material should take into account where millennials live (i.e. cities or suburbs). These examples provide excellent opportunities for a business librarian to talk about market research, specialized industry sources, and demographic as well as population data.

Library Stand Alone Instruction

I am developing a set of online learning modules that are compatible with learning management systems for inclusion in multiple courses or may be used as stand-alone library instruction. The modules are titled: “What is data,” “Discovery and acquisition of data,” “Critical Assessment of data,” and “Synthesize and present data.” (See Table 2).

| Data literacy assignments | Data literacy skill practices | |

|---|---|---|

| Microeconomics | Create a pricing structure using foreign exchange rates plus CPI |

|

| Macroeconomics | Develop indices using GDP to determine market growth rate |

|

| Statistics | Question surveys, Does the tool match the need Does the tool match the need What is the sample size Is it US or global When was it done? |

|

| Finance | Prepare projections for new product development costs and sales |

|

| Accounting | Understand the balance sheet, income statement, cash flows and explain what they reveal about a company |

|

| Marketing | Assess market size and market share |

|

| Management | Prepare charts and graphs and develop narratives |

|

| Module: “What is data?” | |

|---|---|

| Skills | Identify data Identify data types |

| Knowledge | Understand how data type influences its analysis |

| Examples | Quantitative data Qualitative data Categorical data Discrete data Continuous data |

| Module: “Discovery and acquisition of data” | |

| Skills | Create a search statement Select keywords Select data sources |

| Knowledge | Recognize when data can solve a problem, answer a question, strengthen an argument Credible vs non-credible sources Correct citation form Research-related data vs more generalized data |

| Examples | Qualitative data can explain why consumers make certain choices; quantitative data can show how much or when they buy Data from a consumer survey vs general population data from US government |

| Module: “Critical assessment of data” | |

| Skills | Assess data Read charts and graphs |

| Knowledge | Frequency of data Age of data Geographic range of data Data is part of a set or stand alone |

| Examples | Are the people who responded to the poll random samples, or are they millennials who responded to an online survey via Twitter |

| Module: “Synthesize and present data” | |

| Skills | Incorporate found charts and graphs into a research assignment Create tables, charts, graphs, infographics Create models to forecast |

| Knowledge | Presentation should fit the audience and the data Understand that graphics may not represent all data from a given study or survey A model is an approximation |

| Examples | A bar graph is used when multiple variables are tested and are distinct (responses to questions when multiple groups are measured), i.e., millennials vs baby boomers If there is one group, a pie chart can indicate percentage of responses Check models by triangulating data Check which industries move with economy (i.e. travel) and which move with other variables (i.e. education) like population and competition |

Conclusion

The amount of data is only going to increase in the future (Lohr, 2012). While improvements to software tools may make data interpretation clearer and more straightforward, students still need to master critical thinking skills related to data. Some of the skills that librarians can teach are the finding, assessment and citation of data. The more practice students get with these skills, and the more contexts in which they are applied, the more data literate they will become.

The International Association for Social Science Information Services & Technology (IASSIST) has begun to compile data information literacy (which spans the entire data lifecycle from creation through to storage, and metadata) teaching case studies (IASSIST, 2015). I suggest that business librarians create a repository of business-related data literacy instruction. We could support each other as we extend our instructional reach into data literacy. I plan to create such a repository here at EMU. Please send an email to me to contribute or to continue this important discussion.

References

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework#exploration

- Carlson, J., Fossmire, M., Miller, C. C., & Nelson, M.S. (2011). Determining data information literacy needs: A study of students and research faculty. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(2), 629-657. doi:10.1353/pla.2011.0022

- Cooney, M. (2005). Business information literacy instruction: A survey and progress report. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 11(1), 3-25. doi:10.1300/J109v11n01_02

- Detlor, B., Julien, H., Serenko, A., Willson, R. & Lavallee, M. (2011). Learning outcomes of information literacy instruction at business schools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(3), 572-585. doi:10.1002/asi.21474

- Harris, J. (2012, September). Data is useless without the skills to analyze it. Harvard Business Review Blog. Retrieved from http://hbr.org/2012/09/data-is-useless-without-the-skills

- Hunt, K. (2004). The challenges of integrating data literacy intro the curriculum in an undergraduate institution. IASSIST conference, Madison, WI. Retrieved from http://www.iassistdata.org/downloads/iqvol282_3hunt.pdf

- IASSIST (2015). The Data Information Literacy (DIL) Case Studies Directory. Retrieved from http://www.iassistdata.org/resources/data-information-literacy-dil-case-studies-directory

- Koltay, T. (2015). Data literacy: In search of a name and identity. Journal of Documentation, 71(2), 401-415. doi:10.1108/JD-02-2014-0026

- Lohr, S. (2012, February 12). The age of big data. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/12/sunday-review/big-datas-impact-in-the-world.html?_r=0

- Prado, J. C. & Marzal, M. A. (2013). Incorporating data literacy into information literacy programs: Core competencies and contents. Libri: International Journal of Libraries & Information Services, 63(2), 123-134. doi:10.1515/libri-2013-0010

- School of Data. (2016). Data fundamentals: Courses. Retrieved from http://schoolofdata.org/

- Schield, M. (2004). Information literacy, statistical literacy and data literacy. IASSIST Quarterly, 28(2/3), 6-11. Retrieved from http://www.iassistdata.org/sites/default/files/iq/iqvol282_3shields.pdf

- Stephenson, E. & Caravello, P. S. (2009). Incorporating data literacy into undergraduate information literacy programs in the social sciences. Reference Services Review, 35(4), 525-540. doi:10.1108/00907320710838354

Meryl Brodsky is a business librarian at Eastern Michigan University, [email protected].