A Mandatory Diversity Workshop for Faculty: Does It Work?

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article explores the effectiveness of a mandatory training workshop for faculty. Our center for teaching and learning (CTL) was charged with designing and implementing a diversity training workshop for all full-time faculty. The workshop included an introduction to diversity and inclusion, analysis of microaggressions, discussion of inclusive teaching strategies, and practice responding to difficult situations using realistic classroom scenarios. Data were collected on participants’ familiarity and comfort level with diversity and inclusion concepts and situations via identical pre- and post-assessment. A year later, a follow-up survey was administered, which included the original assessment. Assessment and survey responses indicated positive short-term and long-term gains in awareness and use of inclusive teaching strategies.

Keywords: diversity, training, mandatory, faculty

Most college instructors are aware that their students bring a range of backgrounds and experiences to the classroom, and such diversity is usually valued by college administrators, faculty, and students. Even so, institutions of higher education continue to struggle with inequity, ignorance, and incidents fueled by prejudice and racism, particularly in recent years (Artze-Vega et al., 2014; Carnevale & Strohl, 2013; Lawrence, 1990; Musu et al., 2019). Of concern, most college faculty and administrators have minimal, if any, formal training on how to foster an inclusive classroom environment, leverage student diversity, and effectively manage incidents as they arise (Harper, 2018). With no singular, standard approach to diversity training, many institutions create their own programs, which may be provided by centers for teaching and learning (CTLs), campus diversity offices, or human resources departments (Gillespie, 2010). Most CTL offerings are voluntary in nature, and such diversity-related programs tend to attract “frequent fliers” who have already developed a fairly high level of proficiency with the topic (Artze-Vega et al., 2014; Sweet et al., 2017). Moreover, faculty are consumed by many competing obligations, and they typically have limited time for—and potential interest in—such professional development opportunities, particularly those that require an extended time commitment. Given this overall situation, we ask whether it is possible to achieve change in a single, mandatory training session on diversity and inclusion.

The purpose of this study is to examine the effectiveness of a 75-minute interactive diversity and inclusive teaching workshop that was mandated by our university. There are three factors at play here: (a) topic, that is, diversity and inclusion; (b) duration, that is, a single, relatively short workshop; and (c) the session was required rather than optional. In measuring effectiveness of the workshop, we were not able to isolate any of these three factors; therefore, this article presents an analysis of our overall approach. We investigated how faculty knowledge and attitudes change immediately after participating and whether such changes persist over 1 year later. We also investigated what kinds of lasting impressions the workshop made on participants and whether participants made changes to their teaching as a result of the workshop. Such research can help inform efforts at other universities to improve the learning environment for students, particularly if a university is considering mandatory training for faculty as a step toward achieving this goal.

Background

Student engagement, motivation, and receptivity to learning depend heavily on the learning environment. The transition into college, already challenging to most students, is even more difficult for those who have different experiences, backgrounds, and levels of privilege from the majority of their white middle- and upper-class peers and instructors (Kalsner & Pistole, 2003). A given course’s climate, or the “intellectual, social, emotional, and physical environments in which our students learn,” is influenced by a number of factors, some of which can be adjusted by the instructor (Ambrose et al., 2010). For most instructors, building a positive, supportive classroom climate requires deliberate care and effort. This is because higher education as an institution has traditionally not been as inclusive as it could be, and thus changing the status quo means challenging past approaches. For example, Western perspectives are traditionally prioritized in literature, art, and other disciplines and thus are more heavily represented in the curriculum (Ladson-Billings, 1998; Smith et al., 2019). In many disciplines, the standard information delivery mode is often through a lecture, which has been shown to disadvantage racially minoritized students and first-generation students (Eddy & Hogan, 2014). Many instructors do not receive formal training in teaching and, as a result, emulate their own professor or colleagues.

Institutional programming, specifically around diversity and inclusion, has the potential to improve faculty awareness, attitudes, and skills. For example, Booker et al. (2016) found that a summer diversity institute had positive impacts on faculty’s attitudes and pedagogical choices as well as on students’ experiences regarding their sense of community and conflict resolution skills in the classroom. Artze-Vega et al. (2014) discovered approaching diversity and inclusion programming specifically through the lens of stereotype threat resonated more strongly with faculty than a broader approach. Sometimes participation in lengthier programs and institutes on diversity are accompanied with a stipend or some other form of monetary support (e.g., Booker et al., 2016; Mayo & Larke, 2011). Even so, most offerings are voluntary. Instructors are already stretched thin in terms of their various obligations, and if such efforts are not formally recognized by their departments and upper administration, they may focus on other priorities. Thus, it can be difficult to attract participants to optional professional development related to inclusive teaching.

An alternative to optional training is, of course, mandatory training. There are benefits and drawbacks to mandatory training. When a professional development session is mandatory, other factors can contribute to the success or failure of the session—for example, mandatory training can be viewed positively by participants if its message is consistent with overall organizational attitudes and commitment (Machin & Treloar, 2004; Salas et al., 2012; Tannenbaum & Yukl, 1992). Mandatory diversity training in particular is fraught with complication. Dobbin and Kalev (2016) reported on the adverse effects of required diversity training in corporate contexts, in part because these trainings are framed as remedial or accompanied by an aura of “blaming and shaming.” One’s autonomy seems to have a substantial impact on participant attitudes: Legault et al. (2011) found that interventions that eliminate any opportunity for participants to choose to value diversity end up creating more hostility than no intervention at all. Even so, there are strong reasons for administering mandatory diversity training. First, theoretically, all faculty will be impacted, not just those who already have interest or have attended CTL programming in the past. While some participants are resistant or resentful, there is the potential for those participants to be exposed to valuable relevant input from the workshop facilitators or their colleagues. Second, such a strong measure sends a message to the wider university community, particularly the students, that the institution is committed to spending time and resources on education around diversity and inclusion issues. Mandatory professional development for faculty is quite unusual; therefore, when it does happen, it sends a message that the university is taking the issue seriously.

Another concept that warrants noting is the relationship between faculty development and impact on institutional change. A program might result in first-order change (reversible and working within existing constraints), second-order change (deeper, more impactful, and involving permanent transformation), or no change at all (Barth & Rieckmann, 2012; Boyce, 2003). Research shows that sustained efforts around faculty development are more effective for long-term, institutional change than one-off workshops (Chism et al., 2012; Stes et al., 2010). Unfortunately, given faculty’s limited time and potential interest, the enduring culture of academic freedom and faculty autonomy, and constraints on CTL resources, it is difficult to implement a mandatory diversity training session that extends past a single occurrence. Thus, CTL staff must continually grapple with the question of how to maximize impact while minimizing inputs (e.g., time, money, effort).

Our university is a 4-year, private, urban institution located in the northeast United States. It is primarily a commuter school, with international students making up almost 20% of its approximately 7,000 enrolled student population. In fall 2016, our CTL was asked by administration to design and conduct a mandatory diversity training for all full-time faculty in spring 2017. There were a number of factors that contributed to this request. At the time, the university had convened a diversity task force for purposes of drafting a 2-year diversity strategic plan, and a diversity climate survey was released to faculty, staff, and students in early fall 2016. While data were being collected, a student who felt discriminated against by a faculty member published her feelings of pain and frustration in a blog, and the incident appeared on local and national news. In response, CTL was called upon to implement diversity training in the form of a workshop addressing microaggressions for all full-time faculty. Later, after the diversity climate survey was completed and response data were analyzed, the diversity task force also recommended training for faculty and staff in the realm of diversity and inclusion.

Research Questions

The current study explores the effectiveness of a diversity and inclusion training workshop for university faculty by asking the following research questions:

- Q1: What effect does participating in a mandatory diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ relevant knowledge and attitudes (i.e., comfort handling diversity-related classroom issues and confidence implementing inclusive teaching), short term and long term?

- Q2: After participating in a single diversity training workshop, what do participants recall from the workshop 1 year later?

- Q3: What long-term impact does participating in a diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ perceived use of inclusive teaching practices?

Methods

Workshop Design

To help inform the design of the workshop, in late fall 2016, we met with the deans, who each identified faculty needs and offered suggestions regarding workshop design, which included using case studies, incorporating post-election political conflict in some way, keeping sessions as small and intimate as possible, avoiding framing the workshop around the student blog incident, and running a pilot workshop. The deans also recommended a group of faculty with expertise in diversity- and identity-related issues to act in an advisory capacity, and we met with these faculty to solicit their input on an appropriate and productive approach. We also invited the newly hired Director of the Center for Academic Access and Opportunity to join the CTL in the design and facilitation of the workshops.

Based on the input of the deans and the faculty advisory committee, we designed a 75-minute interactive, mandatory session. We ran the workshop in January 2017 with a pilot audience of faculty and a few staff, mostly made up of the faculty advisory committee. The pilot audience provided verbal and written feedback and questions for consideration. Based on their feedback, we revised the workshop.

The finalized goals of the workshop were that faculty should be able to: (a) define “diversity” and “inclusive teaching”; (b) identify concrete strategies for teaching inclusively; (c) analyze common mistakes that widen the diversity gap; and (d) discuss how to handle realistic classroom-based scenarios pertinent to issues of diversity and equity.

The finalized content of the workshop closely reflected these goals. The main sections of the workshop were the following:

- Framing. The facilitators provided verbal framing for the workshop. We explained that the overall purpose of the session was to help faculty consider possible situations, strategies, and perspectives they may not have considered before. We emphasized the importance of open and respectful conversation among colleagues. We acknowledged the sensitivity of and potential difficulty in discussing these topics, and we invited faculty to share their experiences and expertise.

- Defining diversity and inclusive teaching. Faculty were asked to reflect on what diversity “looks like” in their classrooms. As a group, we collaboratively defined “diversity” and “inclusive teaching.” There was discussion about various types of differences among students and how those differences can fall along a spectrum of visible to invisible. We shared our own working definitions for diversity (“Aspects of difference among students, which include social identity groups [race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, etc.] as well as differences relevant to the student learning experience [academic preparedness, educational background, motivation, etc.]”) and inclusive teaching (“Increasing access to academic participation and achievement for all students”).

- Three strategies for inclusive teaching. Faculty were given three strategies for inclusive teaching: (a) emphasize the importance of diverse approaches and viewpoints, (b) practice universal design for learning, and (c) establish a classroom community and behavioral expectations. In small groups, faculty discussed why the strategies promote an inclusive learning environment and how they could implement the strategies in their courses. We also shared our own definition of universal design for learning (“An approach to teaching that aims to optimize learning for all people, regardless of their range of characteristics”).

- Common microaggressions. We presented examples of well-intended but problematic statements (e.g., “Some of my best friends are Black”) and analyzed the speaker’s likely intent and the possible negative impact of the statement on the listener. Faculty were asked to think of additional examples of well-intended but problematic statements.

- Scenario vignettes. In small groups, faculty discussed one of three scenarios: (a) instructor hears students making racist comments; (b) instructor notices that women and Asian students rarely speak in class, negatively impacting their participation grade; and (c) during class, instructor voices their political opinions regarding the 2016 presidential election. Faculty considered the issues presented in the scenario and how it might be better handled by the instructor. The scenarios were debriefed via whole-group discussion.

See the appendix for additional details on workshop design and content.

Workshop Assessment: Design and Measures

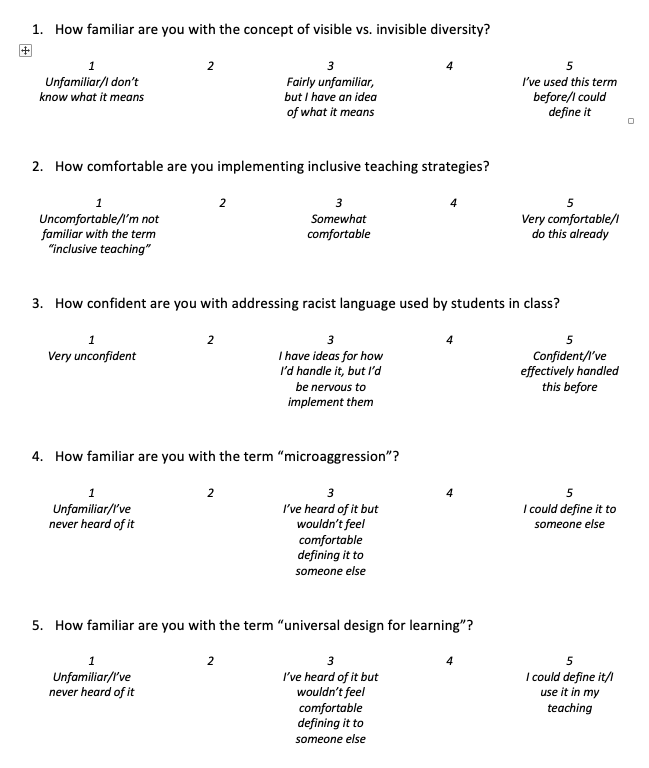

In an effort to measure the short-term effectiveness of the workshop, we developed a pre- and post-assessment to be completed by workshop participants. The pre- and post-assessment was composed of the same five Likert-type questions, for which participants were asked to indicate their response on a scale of 1–5 (see Figure 1).

In spring 2018, we developed a follow-up survey to assess longer-term impact of the workshop. The follow-up survey was distributed online in summer 2018 to all workshop participants and was composed of three prompts:

- Please recall anything you can regarding the content of the diversity workshop for faculty implemented in spring 2017.

- Please complete five Likert-type questions (identical to the pre- and post-assessment questions).

- Did you make any changes in your teaching as a result of attending the diversity workshop implemented in spring 2017? If so, please describe.

All assessments were anonymous. Collection of these data was approved by our university’s institutional review board (IRB).

Participants

Our university is composed of three schools: the college of arts and sciences, a business school, and a law school. Participants in the workshop were full-time faculty in all three schools, tenured and non-tenured, tenure-track and non-tenure track (i.e., lecturers). Department chairs were invited to attend. Because of logistical and resource constraints, adjunct faculty were not required to attend. The total number of full-time faculty invited was 358, with 294 attending a scheduled session.

Workshop Implementation

Each department was consulted to determine the best time for faculty to attend the workshops, which were offered during the university’s activities period, a time slot when no classes are offered. Individual departments were scheduled on Tuesdays throughout the spring 2017 semester. For each workshop, typically two departments were in attendance, with an average of 19 participants in the room.

Participants were served lunch and were seated in groups at round tables. Immediately before the start of the workshop, participants were asked to complete the five-question pre-assessment. The facilitators then led the participants through the interactive workshop, guiding activities and fielding questions along the way. At the end of the workshop, participants were asked to complete the five-question post-assessment as well as a feedback form. We also notified participants of upcoming relevant diversity programming across campus. Though the workshop was described as mandatory, we did not report on individual faculty’s attendance to department chairs or deans.

Within 2 weeks of each workshop, a follow-up email was sent to all of that day’s participants. The follow-up email identified common themes in feedback form responses, provided resources in response to the feedback as appropriate, and invited participants to get in touch if they would like to discuss anything further. The purpose of the follow-up email was to communicate that participant feedback had been heard, to answer lingering questions, and to continue the conversation on diversity and inclusion so that the workshop did not exist in isolation.

In summer 2018, participants were invited to complete a follow-up survey using the online survey software Qualtrics. Participants received an explanation that the purpose of the follow-up survey was to measure the long-term impact of the diversity workshop that had been offered in spring 2017.

Results

Assessment Completion

Of the 358 full-time faculty who attended the workshops, 189 participants completed the entire pre- and post-assessment; an additional 16 participants responded to part of the pre- and post-assessment, and 35 participants responded to at least part of the follow-up survey.

Research question 1: What short- and long-term effects does participating in a diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ relevant attitudes and knowledge?

To measure the short-term impact of the workshop, paired sample t tests were used on the pre- and post-assessment data to determine whether there had been significant improvement in reported attitudes and knowledge for each of the five questions. All five questions showed a statistically significant improvement.

We measured the long-term (i.e., 1 year later) impact of the workshop by comparing pre- and post-assessment data to responses received for the same five Likert scale questions in the follow-up survey. Because the pre- and post-assessment and the follow-up survey were completed anonymously by the 35 participants, we were not able to pair the data, so independent samples t tests were conducted. Of greatest interest was the comparison between pre-assessment data and follow-up survey data, because the results of this comparison would indicate any change in one’s knowledge and attitudes from before they participated in the workshop to over a year later. All five questions showed statistically significant improvement.

We also conducted a comparison between post-assessment data and follow-up survey data to measure whether the gain participants experienced in perceived knowledge and attitudes was further amplified, maintained, or lost over the course of the following year. Of the five questions, two showed significant differences between the post-assessment and 1-year follow-up, and three showed no significant differences.

The sample sizes for the pre- and post-assessment were much larger than the follow-up survey, so we conducted additional weighted independent samples t tests. The weighted tests confirmed the results obtained through the non-weighted t tests. See Table 1 for a summary of results.

| Pre-assessment | Post-assessment | Follow-up | Sample mean difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Pre- to post-assessment | Pre-assessment to follow-up | Post-assessment to follow-up |

| How familiar are you with the concept of visible vs. invisible diversity? | 2.88 | 1.30 | 4.33 | 0.87 | 3.74 | 1.17 | -1.45* | -0.88* | 0.58* |

| How comfortable are you implementing inclusive teaching strategies? | 3.37 | 1.18 | 4.04 | 0.88 | 4.14 | 0.94 | -0.67* | -0.78* | -0.10 |

| How confident are you with addressing racist language used by students in class? | 3.50 | 1.09 | 3.91 | 0.88 | 4.35 | 0.60 | -0.41* | -0.86* | -0.45* |

| How familiar are you with the term “microaggression”? | 3.46 | 1.31 | 4.22 | 1.03 | 4.54 | 0.74 | -0.75* | -1.08* | -0.33 |

| How familiar are you with the term “universal design for learning”? | 2.35 | 1.39 | 4.02 | 1.08 | 3.57 | 1.29 | -1.67* | -1.23* | 0.46 |

Research question 2: After participating in a single diversity training workshop, what do participants recall from the workshop 1 year later?

To determine whether, after a year had passed, participants remembered anything from the workshop, we asked participants to recall anything they could regarding the content of the workshop. This was the first question of the follow-up survey, which ensured that other questions regarding specific diversity-related concepts and situations did not influence their responses. Thirty-two participants responded to the question. We categorized the responses by theme, with some responses spanning more than one theme, and we describe the more major themes below.

Nine responses included recollection of discussions regarding microaggressions and biases and how to exercise strategies to specifically mitigate those phenomena. For example, one participant said that the workshop addressed “how to avoid issues so common in academia today where ideas can be taken as disrespect of others, particularly of students by faculty and staff.” Another remembered “discussions of…being aware of the potential for unconscious bias in the classroom.” Another succinctly articulated their recollection as “Watch what you say.” These recollections aligned with goal 3 of the workshop (“Faculty should be able to analyze common mistakes that widen the diversity gap”).

Seven responses noted the inclusion of relevant classroom-based cases and discussion on how to handle specific situations. One participant remembered that the “training went from fairly clear cases of problematic behaviors into greyer areas”; another recalled “sharing best practices about dealing with problem situations including student comments.” These responses aligned with goal 4 of the workshop (“Faculty should be able to discuss how to handle realistic classroom-based scenarios pertinent to issues of diversity and equity”).

Seven responses recalled memories about the basic format and logistical details of the workshop. Five responses acknowledged discussion around diversity-related concepts, such as “the meaning…of diversity in an academic setting” and “general discussions about what diversity is.” These responses aligned with goal 1 of the workshop (“Faculty should be able to define ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusive teaching’”).

Five responses recalled conversations about general inclusion and inclusive teaching strategies: for example, “how to create a more inclusive environment for students to feel comfortable contributing” and “ways of communication when a diverse group of students are involved.” These responses aligned with goal 2 of the workshop (“Faculty should be able to identify concrete strategies for teaching inclusively”).

Five responses mentioned not remembering much or not remembering anything.

Though unprompted, some responses reflected positive (e.g., “lively,” “valuable,” “good”) or negative (e.g., “leading,” “disorganized,” “rushed”) perceptions of the workshop. Interestingly, a couple responses expressed concern over instances of bias and marginalization demonstrated by their peers during the workshop itself. One participant remembered someone at their table making “a joke about Republicans, and everyone laughed, as though it was assumed everyone at the table was a Democrat.” Another recalled “faculty members discussing character traits associated with foreign students as what I might consider to be gross generalizations.”

Research question 3: What long-term impact does participating in a diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ perceived use of inclusive teaching practices?

In the 1-year follow-up survey, participants were asked whether they made changes in their teaching as a result of attending the diversity workshop. Out of 35 people who responded, 13 (37%) indicated that they did. Of those that did, 12 participants described the changes they made, major themes of which are indicated below.

Six participants described adjusting their teaching to be more inclusive in some way, such as being more conscious of universal design or adding an inclusivity statement to the syllabus. For example, one participant said that they are “trying to think more empathetically with their students, considering their starting point and constraints.” Another described a specific change they had made to teaching course content, moving away from “concepts involving physical, cultural, racial, or gender ‘difference’” and “lean[ing] more toward including examples of cultural celebration” and “things like national culture as defined by Hofstede and others…universal versus more relativistic ways that one could look at culture.” A third reported adjusting cases to be “more inclusive,” sharing examples that “touched upon points about diversity in the workplace.”

An additional two participants provided specific examples of how they now demonstrate value for diverse perspectives in the classroom, which was one of the inclusive teaching strategies presented in the workshop (“Emphasize the importance of diverse approaches and viewpoints”). One participant said they “significantly altered [their] list of reading assignments to include visibly diverse authors.” Another said they make an effort to “find a way to discuss differing perceptions of class topics.”

Three participants described having gained greater sensitivity to language and potentially marginalizing situations. One participant explained, “I am more aware of less visible forms of prejudice or value-laden words and actions in my teaching and exercise greater creating a classroom setting that avoids such prejudice.” Another participant provided an example that incorporated the use of students’ university ID photos:

I used to put up a PowerPoint presentation on the first day of classes. Each slide was a photo of the student, and I’d fill in where they were from and something unique about them as they introduced themselves. After this workshop, I thought I shouldn’t do that in case someone has changed since that freshman photo (I was thinking mostly of changing their gender identity) and didn’t want anyone to see it. I’m more sensitive to that now.

One participant articulated that they gained ideas for how to better handle challenging classroom situations.

Discussion

Research question 1: What short- and long-term effects does participating in a diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ relevant attitudes and knowledge?

All five Likert questions showed significant increase in participants’ perceived knowledge, comfort, and confidence regarding diversity and inclusion. Questions regarding knowledge of specific terminology showed the greatest improvement. Out of all the questions, the question about familiarity with the term universal design for learning had the lowest overall pre-assessment score and showed the most gain—perhaps because universal design for learning is a technical pedagogical term. We suspect these results are explained by the fact that most participants do not encounter diversity- and inclusion-related terminology in their daily lives; therefore, they may have had more room for growth in their knowledge regarding such terminology. Moreover, being able to define a term is an easier skill to gain quickly, as opposed to being able to handle tricky classroom situations or effectively implement inclusive teaching strategies for one’s specific context, which are both more complex and require time and practice.

The question that showed the least increase was about participants’ confidence addressing a student’s racist language, and this result makes sense because the question presents such a difficult, contentious situation. Again, major confidence gains are more likely to come from practice than a single workshop; however, spending a short time discussing strategies with colleagues could help. That said, out of all five questions on the pre-assessment, faculty reported the highest score for confidence addressing racist language, which could be explained by the possibility that instructors had encountered similar situations in the past.

We were not able to pair the data for the comparisons made to determine long-term impact, and the follow-up survey response rate was less than 20%, so it is impossible to know whether the 35 follow-up survey participants are representative of the 189 participants who completed the workshop pre- and post-assessment. After over a year had passed, those participants who completed the follow-up survey showed significant improvement compared to the pre-workshop assessment responses to all five questions. Given the caveats listed above, it is possible that the workshop had a long-term impact in improving the follow-up survey participants’ perceptions of their knowledge, comfort, and confidence regarding diversity and inclusion in a teaching context. The following is discussed with these limitations in mind.

Similar to the short-term impacts, the questions that showed the highest improvement were those related to terminology. Since those terminology-related questions specifically addressed participants’ familiarity with terms, it is reasonable to expect that once the participants had that initial exposure to the terms, they didn’t lose the familiarity they had gained because now they had at least seen the term before. Also, to some extent, the terms lend themselves to being defined intuitively (e.g., visible diversity refers to differences that one can more easily see), so perhaps once the participants had that exposure, it was not difficult for them to retain knowledge of the definitions. That said, the questions about comfort implementing inclusive teaching and confidence addressing racist language actually showed higher mean scores for the 1-year follow-up than did the questions about familiarity with visible/invisible diversity and universal design for learning. This indicates that even though faculty reported substantial improvement regarding terminology, they actually felt greater proficiency with classroom-based contexts—possibly explained by the fact that the participants encounter classroom-based contexts regularly, unlike diversity-related terminology.

The comparison between the post-workshop assessment responses and the 1-year follow-up responses allowed us to determine the extent to which any perceived proficiency gains seen immediately following the workshop were maintained after over a year. There were three questions for which the gain seemed to be maintained, with no significant increase or decrease: comfort implementing inclusive teaching strategies, familiarity with the term microaggression, and familiarity with the term universal design for learning. Participants lost some of the gains they made on familiarity with invisible/visible diversity (about half a point on the 5-point Likert scale), perhaps because they hadn’t considered the term before taking the workshop and unlike, say, universal design for learning, the term is not directly related to teaching, so they may not have thought about it much since. Microaggression, on the other hand, is a term that crops up relatively frequently in and out of academia. The most interesting post-assessment to 1-year follow-up comparison result was the significant additional improvement reported regarding comfort addressing racist language used by a student. Though we are not certain why this would be the case, it is possible that the participants were further exposed to this concept after the workshop occurred. In summer 2017, the Unite the Right rally occurred in Charlottesville, VA, and in response, a series of grassroots forums, programs, and events at our university were launched in fall 2017, including the CTL’s workshop on “preparing for difficult classroom conversations.” The CTL released a newsletter with a teaching tip about responding to challenging classroom moments, and relevant articles were published in The Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed. Such reminders and lasting exposure to topics related to diversity and inclusion could have encouraged participants to continue considering their own teaching strategies and gain further confidence in handling relevant challenging situations.

Regardless of why participants responded the way they did, we believe that efforts around diversity and inclusion are more effective when they are infused across multiple programs, events, and university initiatives. A consistent message helps convey the organization’s commitment to diversity and inclusion, making it more likely to reach those who might not otherwise consider the relevance of these topics to their teaching.

Research question 2: After participating in a single diversity training workshop, what do participants recall from the workshop 1 year later?

Given the importance of repeated practice in order to remember something (Brown et al., 2014; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006; Willingham, 2009), we were not particularly optimistic about how much participants remembered from the workshop. And indeed, some participants acknowledged that they didn’t remember much at all. Others recalled details about the workshop’s format rather than the content. However, the majority of participants who responded to the follow-up survey (72%) did remember content from the workshop, particularly content related to the original intent of the workshop, such as microaggressions and biases, though the workshop was not specifically framed around those topics. This might be because discussions around microaggressions and biases can be particularly sensitive, especially if a participant discovers that they had unwittingly committed a microaggression or harbored a bias. At times during the workshop, conversations involved a participant expressing confusion about what is “wrong” with using certain language (e.g., inviting a Chinese student to offer their perspective on a Chinese political issue) and colleagues responding tactfully but honestly.

Participants also noted recollections about classroom-based scenarios, which may have been memorable because they make the workshop concepts concrete and relatable. During the workshop, some participants noted that they had experienced those very situations; others couldn’t imagine ever encountering them. A major goal of the workshop was to impart inclusive teaching strategies, and some participants remembered the discussions around those.

It is notable the degree to which a couple of participants remembered conversations that concerned them—conversations in which a colleague made insensitive remarks or inappropriate assumptions among their peers. Even a year later, the participants could recall the details of these encounters. This illustrates the importance of considering how students might be impacted in the long term by similar encounters with their instructors, made more complex and potentially damaging given the power dynamics inherent in the student-instructor relationship.

Research question 3: What long-term impact does participating in a diversity training workshop have on faculty participants’ perceived use of inclusive teaching practices?

Ultimately, our workshop was designed to have a positive impact on the student experience, since a major impetus for the workshop was in response to a student feeling prejudiced against and invalidated by an instructor. Thus, we hoped that participants would take what they learned from the workshop and begin exercising more inclusive teaching strategies in the classroom. When asked in the 1-year follow-up survey whether they made changes in their teaching as a result of attending the workshop, approximately a third of participants said they had. This result is encouraging: if the follow-up survey participants are representative of the entire population of workshop participants, almost 100 faculty might have adjusted their teaching to be more inclusive. Even without making such a generous assumption, changing the practices of even 10% of faculty would be an achievement, given the fact that the participants were not attending by choice.

The changes that the participants described were in line with what the workshop endorsed. Some were directly relevant to the participant’s course content; others were more general pedagogical strategies. Some changes described were straightforward (e.g., adding an inclusivity statement to the syllabus; altering the reading list to include more diverse author perspectives); others were vaguer (e.g., being “more sensitive to situations that might be perceived as being intolerant of diversity”). Regardless, these changes have the potential to signal to students that the classroom is a place where they can feel supported—in other words, these changes could have an impact on a student’s sense of belonging and affinity for the discipline.

Lessons Learned

In light of any successful results, a few additional notes and lessons learned are worth discussing. We quickly learned that the framing at the beginning of such a workshop can have a critical impact on the willingness of participants to engage openly with the conversations that followed. When we framed the workshop as an open, supportive conversation that allowed faculty to explore situations they perhaps hadn’t considered before, when we recognized that some faculty may already have expertise in diversity and inclusion, and when we acknowledged the sensitivity and difficulty in discussing the topics, the following conversations were more successful. In the first couple iterations of the workshop, this framing was lacking, and participants tended to ask more questions about what had been done by upper administration about the incident and why all faculty needed to attend this workshop. We were also aware of sensitivity around the term microaggression, and rather than use the word to introduce the concept, we facilitated a segment on “well-intended but problematic statements” and defined the term microaggression during the debrief.

Another issue we encountered was that faculty felt that the workshop didn’t reflect a genuine effort on the part of the university to address concerns around diversity and inclusion. Some faculty compared the workshop to “ticking a box” and that diversity and inclusion had only been addressed at a superficial level. These perceptions may have been amplified by the fact that some faculty felt the workshop was a punitive measure and that the incident had not been fairly or transparently addressed.

Mandatory trainings can present problems in the form of resistance. However, even with such resistance, we hypothesize that there is value to conducting such trainings. Broad level, institution-wide cultural changes take time, and initiatives like mandatory training may serve to seed attitudinal changes, if only through exposure. It is possible that some threshold level of participation is needed in order to achieve buy-in and positive change, as with implementing student-centered pedagogies (Shaw et al., 2019).

To ensure that participants had an opportunity for continued engagement beyond the workshop, we collaborated with other units on campus to offer additional relevant sessions in spring and fall 2017, such as an implicit bias workshop, a microaggression scenario discussion, and a presentation by an interactive theatre group involving bias in the classroom. These offerings were not mandatory, and we saw mixed success in terms of attendance. This approach is supported by the idea that multidimensional diversity learning can, over time, alter the behaviors and attitudes of some individuals and ultimately create a ripple effect in which those individuals influence other colleagues’ behaviors and attitudes (Fujimoto & Härtel, 2017). Ultimately, the CTL decided to pursue an infusion model, in which almost all programming offered is considered through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusion: for example, a session on active learning would include discussion around the fact that active learning has been shown to close certain achievement gaps (Eddy & Hogan, 2014). We also incorporated a session similar to the mandatory diversity workshop into the annual new faculty orientation. Since most new full-time faculty attend new faculty orientation, this approach allows us to sustain the goal of ensuring that almost all full-time faculty have undergone training on diversity and inclusion in the classroom. We have noticed that participants in the new faculty orientation version have been more open and engaged than participants in the mandatory session. A benefit to the infusion model is that diversity and inclusion are not simply treated as stand-alone topics; rather, they are relevant to most if not all aspects of teaching and learning, including course design, assessment, group work, classroom management, and more.

Since the time of the workshops, the university has expanded its commitment to diversity and inclusion efforts. The diversity task force has been dissolved, and the former Director of the Center for Academic Access and Opportunity has moved into the position of Vice President for Diversity, Access, and Inclusion.

Limitations and Future Research

Our interpretations of the results should be considered with a caveat. Though our quantitative results indicated improvement both in the short and long term, it is difficult to know whether this improvement is representative of true change in the participants for two reasons. One is that participants’ responses were self-reported measures of their perceived confidence, familiarity, and comfort with challenging classroom situations. Self-reports are indirect measures; we did not directly observe changes in participants’ teaching practices, nor did we ask them to define diversity-related terms. Even the follow-up survey question about changes in practice that resulted from attending the workshop involved self-reports rather than direct measures. Indirect measures are problematic, particularly because people who are less skilled in a given area tend to be unaware of their deficiencies and overestimate their abilities (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Faculty have been shown to rate themselves disproportionately high in terms of teaching ability, such that most feel they are above average (Cross, 1977). In the future, more direct measures of change could be collected: for example, change in teaching artifacts before and after participating or observations of faculty teaching in the classroom before and after participating.

Second, regarding long-term improvement, the follow-up survey sample size was small. We sent the follow-up survey to all the original workshop participants, and because all data was collected anonymously, we could not pair follow-up survey responses with workshop pre-/post- assessments, nor could we assume that all the follow-up participants also completed the original pre- and post-assessment. Completion of the follow-up survey was voluntary; thus, the follow-up survey population may be a non-representative group of participants (e.g., faculty who care deeply about diversity and inclusion, faculty who felt strongly about the original workshop, faculty who regularly open email, etc.).

Finally, the follow-up survey prompted participants to report changes in teaching as a result of attending the workshop but did not address other changes that might have occurred, such as general attitudinal changes around the topics of diversity and inclusion. It is possible that the workshop had an impact in these realms beyond what we measured. Some faculty later shared, unprompted, that they got a lot out of the workshop and that it made a significant difference in the way they view diversity and inclusion. For example, one faculty member said his eyes were opened to the concept of invisible diversity, which had been addressed in the workshop, and the notion that “equal” treatment of all students does not necessarily mean all students will have the same experiences in the classroom (in essence, he recognized the difference between equity and equality). Another faculty member described how the workshop had piqued his interest in engaging scholarly work around diversity and inclusion and that he is now working on a chapter for a book on race and social equity. Conducting focus groups in the future may help capture a broader lens of the workshop’s impact.

Conclusion

The mandate for diversity training afforded the CTL an unusual opportunity to design and conduct a workshop on diversity and inclusion for all full-time faculty at a 4-year private university. During this experience, we encountered challenges, including faculty resistance, and we learned lessons, including the importance of careful framing and maintaining a sustained effort around diversity- and inclusion-related CTL programming. Despite these challenges and lessons, the results of the workshop are encouraging: they indicate long-term positive impact on faculty’s perceptions of familiarity with relevant concepts and adeptness at handling challenging situations and, to a limited extent, resulted in more inclusive teaching practices. Future efforts should include continuing to infuse an inclusive teaching approach in other CTL offerings and conducting more direct measures of impact on faculty participant behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge.

Biographies

Heather Dwyer is currently Assistant Director at Tufts University’s Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching. Prior to joining Tufts, she worked at the Center for Teaching and Scholarly Excellence at Suffolk University, where the article’s scholarly work was conducted. Dr. Dwyer’s professional interests include evidence-based teaching, inclusive teaching, and measuring the impact of CTL efforts. She earned her doctorate in Ecology at University of California, Davis.

Joyya Smith, EdD, is the Vice President of Diversity, Access, and Inclusion at Suffolk University. She supports institutional initiatives that foster the expansion of diverse representation among the campus community while promoting inclusion. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology, a master’s degree in Higher Education Student Services from Georgia Southern University, and a doctorate in Education, with a concentration in educational leadership from Argosy University/Atlanta.

References

- Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

- Artze-Vega, I., Richardson, L., & Traxler, A. (2014). Stereotype threat–based diversity programming: Helping students while empowering and respecting faculty. To Improve the Academy, 33(1), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20003

- Barth, M., & Rieckmann, M. (2012). Academic staff development as a catalyst for curriculum change towards education for sustainable development: An output perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 26, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.12.011

- Booker, K. C., Merriweather, L., & Campbell-Whatley, G. (2016). The effects of diversity training on faculty and students’ classroom experiences. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2016.100103

- Boyce, M. E. (2003). Organizational learning is essential to achieving and sustaining change in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 28(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ihie.0000006287.69207.00

- Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., III, & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Harvard University Press.

- Carnevale, A. P., & Strohl, J. (2013). Separate and unequal: How higher education reinforces the intergenerational reproduction of white racial privilege. Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/separate-unequal/

- Chism, N. V. N., Holley, M., & Harris, C. J. (2012). Researching the impact of educational development. To Improve the Academy, 31(1), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2012.tb00678.x

- Cross, K. P. (1977). Not can, but will college teaching be improved? New Directions for Higher Education, 1977(17), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.36919771703

- Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2016, July–August). Why diversity programs fail and what works better. Harvard Business Review, 52–60.

- Eddy, S. L., & Hogan, K. A. (2014). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

- Fujimoto, Y., & Härtel, C. E. J. (2017). Organizational diversity learning framework: Going beyond diversity training programs. Personnel Review, 46(6), 1120–1141. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2015-0254

- Gillespie, K. H. (Ed). (2002). A guide to faculty development: Practical advice, examples, and resources. Anker Publishing.

- Harper, S. (2018). Keynote address. Leading for Change Higher Education Diversity Consortium Fall 2018 Summit, Somerville, MA, United States.

- Kalsner, L., & Pistole, M. C. (2003). College adjustment in a multiethnic sample: Attachment, separation-individuation, and ethnic identity. Journal of College Student Development, 44(1), 92–109.

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/095183998236863

- Lawrence, C. R., III. (1990). If he hollers let him go: Regulating racist speech on campus. Duke Law Journal, 1990(3), 431–483. https://doi.org/10.2307/1372554

- Legault, L., Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2011). Ironic effects of antiprejudice messages: How motivational interventions can reduce (but also increase) prejudice. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1472–1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611427918

- Machin, M. A., & Treloar, C. A. (2004, September 29–October 3). Predictors of motivation to learn when training is mandatory. 39th Australian Psychological Society Annual Conference, Psychological Science in Action, Sydney, Australia. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/717/

- Mayo, S., & Larke, P. J. (2011). Multicultural education transformation in higher education: Getting faculty to “buy in.” Journal of Case Studies in Education, 1, 1–9.

- Musu, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. (2019, April). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2018. National Center for Education Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/iscs18.pdf

- Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255.

- Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(2), 74–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612436661

- Shaw, T. J., Yang, S., Nash, T. R., Pigg, R. M., & Grim, J. M. (2019). Knowing is half the battle: Assessments of both student perception and performance are necessary to successfully evaluate curricular transformation. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210030.

- Smith, L. T., Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2019). Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view. Routledge.

- Stes, A., Min-Leliveld, M., Gijbels, D., & Van Petegem, P. (2010). The impact of instructional development in higher education: The state-of-the-art of the research. Educational Research Review, 5(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.07.001

- Sweet, C., Carpenter, R., & Blythe, H. (2017). Reaching those faculty not easily reached: How CTLs can improve participation in faculty programming through faculty innovators and online instruction. Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, 9, 73–83.

- Tannenbaum, S. I., & Yukl, G. (1992). Training and development in work organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 399–441.

- Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Appendix: Workshop Design and Content

5 minutes: Introduction

- Framing

- Participants complete pre-assessment

10 minutes: Defining diversity and inclusive teaching

- Writing prompt: What does diversity look like in your class?

- Show continuum from visible to invisible diversity

- Share the facilitators’ working definitions of diversity and inclusive teaching

15 minutes: Strategies for inclusive teaching

- In small groups, participants discuss how they would apply one (assigned) of three inclusive teaching strategies:

- Emphasize the importance of diverse approaches and viewpoints

- Practice universal design for learning (optimizing learning for all students, regardless of cultural background, academic experience, and ability status)

- Establish a classroom community and behavioral expectations

- Debrief and define “universal design for learning”

15 minutes: Microaggressions: intent vs. impact

- Explain intent vs. impact using an example (“Some of my best friends are [Black, gay, Muslim, Asian, etc.]”)

- In small groups, participants identify intent and impact for the following two examples:

- Asking a student to speak on behalf of their identity group. Example: “So, as we can see, the social structures of India are heavily impacted by its slums. Radhika, you’re Indian—what can you tell us about this?”

- Using the terms illegal immigrant or illegal alien. Example: “Let’s discuss the cost repercussions of illegal aliens on the U.S. economy.”

- Debrief and define the term microaggression

25 minutes: Scenario vignettes

- In small groups, participants discuss one of the following scenarios:

- An instructor overhears students making racist comments during small group discussion. To avoid an uncomfortable confrontation, the instructor says nothing.

- An instructor has allocated 15% of the grade toward class participation. The instructor notices that women and Asian students rarely speak up in class. Based on the grade breakdown, most of these students would receive a lower grade than their classmates because of their lack of verbal participation.

- An instructor is asked by some students during class to voice an opinion on the election. The instructor says, “Things didn’t turn out how we had hoped, but remember, we are the majority and most of us voted not to have that kind of leadership. The next 4 years will be tough, but we need to come together as a nation.”

- As a large group, debrief at least one of the scenarios

5 minutes: Closing

- Share relevant resources and upcoming programming

- Participants complete post-assessment and feedback forms