Impostor Phenomenon in Educational Developers: Consequences and Coping Strategies

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

A recent survey of educational developers revealed that nearly all respondents (96%) had experienced impostor phenomenon (IP) in their professional lives. Here, we use survey data to investigate the consequences of and coping strategies for IP among educational developers. We describe the repercussions of IP for the personal and professional lives of educational developers (including stress, lowered self-esteem, not speaking up, and diminished career trajectories), the ways in which they cope with IP, and the unique ways that they may be positioned to leverage their own experience with IP to work more effectively with instructors.

Keywords: impostor phenomenon, impostor syndrome, educational developers, identity

Introduction

Impostor phenomenon (henceforth IP, often called “impostor syndrome,” although it is not classified medically as such) is the belief, despite evidence to the contrary, that one has fooled others into overestimating one’s abilities and will eventually be exposed as a fraud. It was first described by Clance and Imes in 1978. Later, Harvey and Katz (1985) described its three main signs: (a) believing that one has fooled others into overestimating one’s own abilities; (b) attributing personal success to factors other than one’s ability or intelligence, such as luck or an evaluator’s misjudgment; and (c) fearing exposure as an impostor. According to Young (2011), impostors are masters of explaining away their successes, telling themselves the following: “I got lucky”; “I was just in the right place at the right time or the stars were right”; “it’s because they like me”; “if I can do it, anyone can”; “they must let anybody in”; “someone must have made a terrible mistake”; “I had a lot of help”; “I had connections”; “they’re just being nice”; and “they felt sorry for me” (pp. 18–19).

IP has long been described and studied in higher education, among both faculty (e.g., Bahn, 2014; Gravois, 2007; Kasper, 2013; Keenan, 2016; Rippeyoung, 2012) and graduate students (e.g., Aguilar, 2015). It seems to be particularly pervasive among, though certainly not exclusive to, women (Clance & Imes, 1978; Keenan, 2016) and minorities (Cokley et al., 2013; Dancy & Brown, 2011). A recent study found that educational developers also experience IP. Rudenga and Gravett (2019) described data in which 96% of survey respondents reported experiencing IP at some point in their professional lives, with a majority identifying with each of the three main signs described earlier. Respondents attributed their experience of IP to various intersecting facets of their identities, experiences in graduate school, career shifts, or being early in their careers—all in line with other IP research. They described experiencing IP most strongly during large, new, or highly visible tasks, but for nearly every task educational developers commonly perform in their work, a majority of respondents found the situation to be IP-inducing. In an interesting insight into the field, participants described IP arising particularly from the lack of any “official” credentials available to them in the field of educational development, the perception among colleagues that ours is a “cop-out” field for “failed academics,” and being expected to serve as experts while being treated as inferiors. While this study provided a window into the prevalence and manifestations of IP among educational developers, no one has yet described the consequences of IP in that population, the coping mechanisms that are used most commonly or most effectively, or the unique ways they may be situated to leverage IP experience to support others dealing with similar feelings.

Previous research points to consequences of IP on one’s “self-esteem, professional goal-directedness, locus of control, mood, and relationships” (summarized in Brems et al., 1994), and the literature suggests a wide variety of other possible consequences as well (e.g., in Bahn, 2014; McElwee & Yurak, 2010). Published strategies for combating IP focus on talking to others, coming to grips with imperfection, focusing on strengths, and identifying and revising the ways one talks to oneself (e.g., Kaplan, 2009; Young, 2011). Here, we apply the broader knowledge of consequences and coping strategies for IP to the specific field of educational development, using survey data to describe the repercussions of IP for the personal and professional lives of educational developers, the ways in which they contend with IP, and the unique ways that they may be positioned to leverage their own experience with IP to work more effectively with instructors.

Methods

We distributed an IRB-approved survey to the POD Network Google Group, a listserv for primarily U.S.-based educational developers. We collected ratings and short answers about IP experiences among this group, including the consequences of IP and methods used to cope with it. We share both quantitative and qualitative data below, providing samples of short answer responses to illuminate themes and broader findings.

A total of 156 educational developers responded to the survey, with demographics (76% female, 90% white) resembling that of the POD network. Thirty-four percent of respondents reported involvement with the field for 0 to 4 years; 32% have been involved for more than 10 years. We acknowledge that our sample may be skewed toward those who have experienced IP; however, as we are focused here on describing consequences and coping strategies in those who do experience it, and as we are not performing inferential statistical analyses, we do not think that this detracts from our results.

Consequences of IP

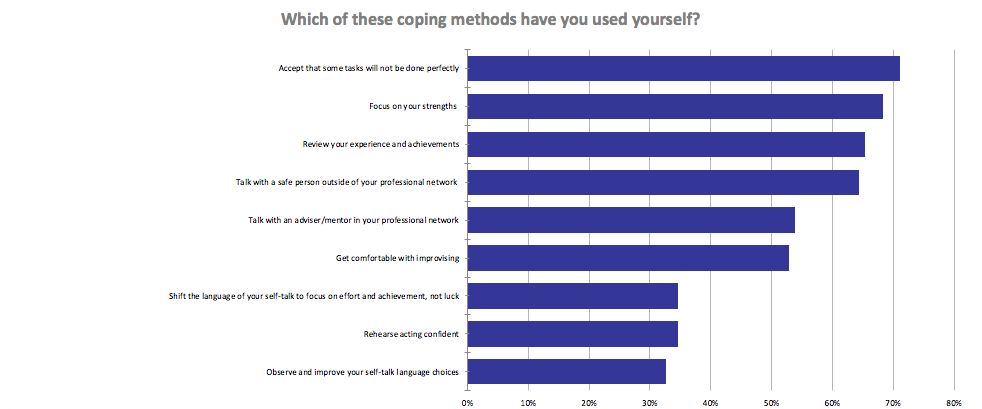

Respondents indicated that the areas of their lives most influenced by IP (based on the list from Brems et al., 1994) were their self-esteem (with 66% of respondents experiencing such consequences somewhat or to a great extent), professional goal-directedness (62%), and mood (61%). Respondents also indicated that IP impacted their locus of control (54%) and relationships (46%). It is striking that, for nearly every consequence listed, over half of respondents found that IP had influenced that area (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Survey respondents identified the extent to which IP has influenced each of the areas that were identified by Brems et al. (1994) as a common consequence of IP.

Figure 1. Survey respondents identified the extent to which IP has influenced each of the areas that were identified by Brems et al. (1994) as a common consequence of IP.Like other academics, educational developers who responded to our survey reported experiencing a wide range of related and additional consequences resulting from IP. Although the survey question explicitly indicated that consequences could be negative, positive, or neutral, qualitative comments were overwhelmingly focused on negative consequences. Nearly all responses (over 90%) included one or more overtly negative consequences; over 60% of the comments in this section of the survey were solely negative. The most striking and frequent consequences that emerged from the comments were the following:

- stress and anxiety

- reduced self-esteem

- not speaking up

- negative impacts on career trajectories

- a tendency to work harder

- lowered quality of work

- an increased growth mindset

- changes to connections with colleagues

While these themes are, of course, tightly interwoven, we explore them individually below.

The most frequently described consequence of IP was stress and anxiety, which respondents described as having ramifications that spread throughout their lives. Respondents revealed that the stress and anxiety resulting from IP did not simply affect their roles as educational developers. Respondents experienced consequences that impacted their health, their personal relationships, and their aspirations. Indeed, 46% of respondents described IP as influencing their relationships with others somewhat or to a great extent; 61% described IP as influencing their mood somewhat or to a great extent. Comments suggested that those influences were closely tied to stress and anxiety:

There is a lot more stress, which does affect my sleep, and to some extent my health.

I’ve had to use a lot of mental and emotional energy to “squash” the IP so that I could perform in the given situation. It takes a lot of energy to “hide” IP.

The amount of stress and anxiety I have in preparing or approaching specific aspects of my life; but also the feeling of not being able to have a healthy work/life balance (and then actually not having a healthy balance, and the negative health impacts).

These kinds of comments indicate that IP, and the pressure to hide it or compensate for it, leads to increased stress and anxiety, which then leads to further damaging consequences to respondents’ health and relationships. The results described included loss of sleep, declining physical health, and damaged connections with personal friends and professional colleagues. All of these accord with earlier research on IP in other populations (e.g., Bahn, 2014; Clance et al., 1995).

Other respondents described lower self-esteem, reflecting the finding that 66% had experienced IP influencing their self-esteem somewhat or to a great extent.

Huge loss of confidence which permeated into my life generally making me unhappy and it seriously affected my marital relationship.

As a result of Imposter Phenomenon, I have lower confidence in my work, especially when communicating with others at the university (especially Assoc Deans, Vice Provosts, etc.). I second guess some of my choices on a daily basis.

It makes me less confident in my abilities and afraid of messing up a particular event. I have a bit of fear of failure so as a result I spend a lot of my free time worrying about and trying to get all the parts in order so I don’t. I feel like I lose out on participating in social events or relaxing when this happens.

Again, we see IP leading to lower self-esteem (though some respondents reflected that it is hard to tell which came first, the IP or the lower esteem), which subsequently leads to negative impacts on the person’s work as well as on their relationships, health, and ability to relax. The pervasive impact of this lowered self-esteem and its effects is striking: they “second guess some of [their] choices on a daily basis,” “spend a lot of [their] free time worrying,” and find it “generally making [them] unhappy.”

One consequence closely interwoven with lowered self-esteem but which arose with surprising frequency as its own specific effect, is not speaking up:

I discount myself or do not speak up despite knowledge and what could be relevant contributions.

I lose my voice in meetings, consults, and collaborations.

When interacting with most of the faculty in the department where I will be receiving my PhD, I am hesitant to be an expert.

I am sometimes very timid and reluctant to offer suggestions with any kind of authority (like, who am I, to suggest this to this person?). I think my recommendations often come across as very tentative.

If IP causes an individual to “lose [their] voice,” then that is troubling both for the individual and for their colleagues, as the individual may refrain from contributing or sharing knowledge for fear of being found out. This becomes even more troubling, however, in light of the finding that those from marginalized groups may be most likely to experience IP (Clance & Imes, 1978; Cokley et al., 2013; see also Parkman, 2016). If IP disproportionately causes individuals from underrepresented or oppressed groups to not speak up, then it is systematically minimizing the contributions of those from already marginalized groups to our institutions and our field. This underscores the importance of working at a structural level (e.g., within the POD Network) to understand and mitigate the consequences of IP.

In addition to internal psychological difficulty and lost contributions due to IP, the decrease in confidence respondents describe related to their IP has concrete negative consequences for their career trajectories. With 63% reporting IP as influencing their professional goal-directedness somewhat or to a great extent and 54% reporting it influencing their locus of control somewhat or to a great extent, respondents shared comments such as:

I have given up part way through applying for some very promising positions (both educational development and tenure-track faculty) and I have chosen not to apply and/or reapply to some because they just seemed too intimidating.

I have not gone up for promotion already, which my Dean and colleagues think I should have.

I haven’t taken myself or my career path as seriously, deliberately, or confidently as I otherwise might have.

I don’t seek out more ambitious things, like writing a book, which seem beyond what I think of as what I can do well.

Most responses along this theme referred to applying to new positions or going up for promotion. Others described more specifically the hesitance to take on particular projects or pursue research that wasn’t squarely within their area of training. Over time, this can lead to a significant loss of earnings and recognition, which again becomes even more troubling when considering the groups of people who may be most likely to experience IP, as such a pattern may reinforce existing structural inequities.

Finally, as a result of the feelings of inadequacy and fear of exposure, as detailed above, many of the respondents also expressed that they push themselves and work harder. In particular, many reported working especially hard at preparation (sometimes to the point of self-identified “over-preparation”) to ensure they would not feel like an impostor in an intimidating situation.

I think it’s pushed me to work twice as hard and to be twice as good.

I put in many extra hours prepping for workshops and things because I want to be perceived as knowledgeable.

We find this consequence troubling on both an individual and a structural level. We are concerned that for those feeling undeserving and fraudulent, the mere addition of more work may not result in a dissipation of IP. Huston (2009) described the tendency to overwork to mask insecurities as a hallmark of faculty who were “strained and anxious” in their teaching. Furthermore, the same groups (notably women and/or underrepresented minorities) that may be most susceptible to IP (Clance & Imes, 1978; Cokley et al., 2017; Dancy & Brown, 2011) have also historically been expected to take on extra work—for example, in academia, through teaching, advising, and service (e.g., O’Meara et al., 2008), or at home, with “the second shift” (Hochschild, 1989). Thus, the implied recommendation that these already overburdened individuals simply must work harder in order to reduce or eradicate IP is highly problematic, even if some respondents described this push as a positive.

Positive Consequences of Impostor Phenomenon?

Of course, as one respondent rightly noted, “there is a fine line between negative and positive experiences.” Another wrote that “there may also be benefits and positive outcomes.” Indeed, nearly a third (29%) of the comments on the consequences of IP reflected respondents’ awareness that there could be both negative and positive effects of IP (though less than 8% listed solely positive consequences, without any negative accompaniments).

A primary theme of the positive consequences responses was that IP pushed respondents to adopt a growth mindset:

That there is room for growth, that improvement is possible, that we can learn from failures.

IP isn’t just about feeling not good enough, it’s about understanding that it is always possible to improve.

It is interesting that IP and the growth mindset—a belief that one can grow and change with effort (Dweck, 2007)—are linked in the minds of many of our respondents. The rich, complex web of affective elements of professional life is difficult to disentangle, to be sure. However, we posit that the perception of IP as being “about understanding that it is always possible to improve,” which multiple respondents expressed, may conflate research on the growth mindset with IP in a way that strays from the original definition of IP. While there is great value in creating positive outcomes from a difficult experience like IP and adopting a growth mindset, it is worth recalling that the root of IP is the belief, despite evidence to the contrary, that one is an impostor who does not deserve one’s success. This is distinct from a healthy awareness of one’s own shortcomings and from knowing that, as a newcomer to the field, for instance, you have room to learn and grow. In the latter cases, certainly, a healthy dose of growth mindset and hard work is an appropriate and important antidote. However, by definition, IP consists of fraudulent feelings, regardless of qualification, preparation, or success. It is admirable that individual respondents have found motivation and creative routes to improvement, but this version of understanding IP departs from what Clance and Imes (1978) and others have described. This understanding becomes particularly risky when it leads an individual to suggest a hard-work-based growth mindset as a broader solution to IP, potentially belittling the experiences of those struggling with IP and reinforcing the structural inequities described above.

The other theme that emerged within “positive consequences” is deeper connections with colleagues:

I also have been able to help others when I mentor, however, by revealing that I feel imposter syndrome.

Having open conversations about IP has brought a unity and closeness with colleagues.

Several respondents echoed experiences of increased unity, closeness, and ability to help as a result of IP. It is worth noting the key mediator here: these positive consequences only emerge after “revealing” or “having open conversations about” IP. This stands in stark contrast to the responses described above, which described IP as highly isolating, when respondents felt they had to “hide” or “squash” their IP. While there may be risks involved in revealing impostor feelings, depending on one’s positionality and community, such vulnerability seems to make the difference between IP being a disconnecting experience and being a connecting one.

Finally, IP can become a valuable experience of personal vulnerability that allows you to connect more meaningfully with the instructors you serve.

Having feelings of being an imposter has helped me in working with faculty to redesign their courses. They are experts in their fields but feel very uncomfortable when we discuss design principles and technology that they are not familiar with. It is an uncomfortable feeling for them. I believe that they often have that same imposter syndrome and don’t want to feel “exposed,” so I make a conscious effort to make them feel comfortable and safe.

They tend to see me as very together and accomplished and seem to feel better that I’ve felt imposter syndrome, too.

As mentioned above, academics are known to experience IP (Young, 2011), and it is a safe bet that a large fraction of your colleagues have either experienced IP in the past or are currently experiencing it. Just as your own classroom experience can help you identify with the day-to-day challenges of instructors, your own experience of IP can help you identify with the internal challenges they face. This may happen implicitly, as in the above effort to “make them feel comfortable and safe,” which is based in the respondents’ own IP but does not name it as such, or explicitly, as in the case of the respondent who specifically shared their own IP experience and helped their consultees feel better.

Of course, to capitalize on this potential benefit of IP requires vulnerability on the part of the educational developer. Such vulnerability—provided that it remains appropriate and within the comfort zone of the educational developer—is both immediately useful to instructors and sets a good example for classroom application. Just as Felder (1988) advised engineering instructors to mention IP in classes and to suggest that students talk to one another about their experiences with it, we propose that discussing IP in workshops or consultations is an excellent step toward helping our colleagues identify and begin to cope with it. Normalizing the feelings associated with the phenomenon and offering a few suggestions for dealing with it can go a long way toward helping educators cope with it in a positive way. Educational developers may also find this to be an important way to turn their own difficulties into a valuable asset in building connections.

Coping with Impostor Phenomenon

Suggestions for Coping with Impostor Phenomenon as an Educational Developer

Despite some positive consequences, respondents overwhelmingly indicated the presence of IP as a stressor in their lives, with wide-ranging professional and personal repercussions suffered as a result. Given those risks and repercussions, it was important to also find out from respondents how they themselves coped with IP.

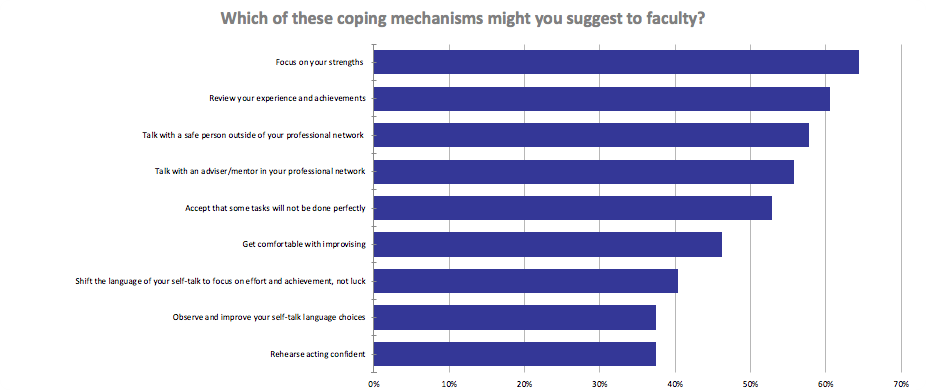

From a list supplied on the survey, which was based on the work of Kaplan (2009), the coping mechanisms most frequently utilized by the educational developers who responded were accepting that some tasks will not be done perfectly (74%), focusing on your strengths (71%), reviewing your experience and achievements (68%), talking with a safe person outside of your professional network (67%), talking with an adviser/mentor in your professional network (56%), and getting comfortable with improvising (55%). See Figure 2.

Although “accept that some tasks will not be done perfectly” was the top response to the above question, when asked which of the above coping mechanisms were most helpful and why, respondents focused their qualitative comments predominantly on talking with others.

Getting an outside perspective as a reality check is very useful, since IS [impostor syndrome] is based on uncertainty about one’s competency. Outside mentors who know you can tell you where you actually have to improve.

Talking with other professional developers and with mentors has been the greatest help, as has talking with other peers as described above. To realize one is not alone is to realize one is not really an impostor.

Most helpful has been talking with trusted mentors who affirm the contributions I have made and the work I have done to be where I am today.

Discussing these feelings with “safe” people has helped me to realize that I am not the only person feeling this way. Knowing this has helped me tremendously. These safe people will reiterate my accomplishments and indicate their confidence in my abilities, which also helps me refocus.

They specified others from both within and outside of professional networks: mentors, peers, family, partners, friends, and therapists. Talking with others can, as one respondent noted, be “wonderfully encouraging and affirming.” Respondents indicated that such supportive others could serve as a reminder that they are not alone, affirm their contributions, and remind them of their successes—suggesting that supportive conversation partners can reinforce other coping mechanisms.

It is interesting that 67% of respondents reported talking with a safe person from outside their professional network, and just 56% reported talking with an adviser/mentor in their professional network, making these the fourth and fifth most commonly used strategies—yet these are overwhelmingly the most commonly cited “most helpful” strategies. We suggest that, since talking to a trusted other is “most helpful” for so many people, yet nearly a third of sufferers never employ that strategy, the veil of secrecy that can surround IP can actively damage sufferers’ ability to combat IP by creating a barrier to a highly effective coping strategy.

Many respondents also commented on the value of reviewing their accomplishments or focusing on their strengths.

Reviewing accomplishments. It always surprises me how much I’ve really done.

Focusing on my strengths has helped me identify the unique contributions I can make, even when others in the room might have greater experience or knowledge than I do.

Reviewing experiences and achievements—most useful because they are real—they happened.

While many people may find a self-esteem boost in reviewing accomplishments or focusing on strengths, it is a telling hallmark of IP that respondents refer specifically to shock at “how much I’ve really done” or remembering that achievements “are real—they happened.” Respondents also referred to how easily this knowledge can be forgotten, citing a need to remind themselves frequently, especially before major events or in moments of heightened IP.

Other respondents listed learning to improvise as a key coping mechanism:

The nature of being an educational developer is to be put into a number of different situations where you are answering questions and/or making suggestions on the fly. I was horrible at improvising before this position, but through sheer necessity, I have become better, though not perfect. The more I can improvise and still sound coherent, the more confident I become in those situations.

Getting comfortable with improvising—which would include seeking additional information in the moment is probably the most important coping mechanism I have used. I find it works best if I acknowledge that I can learn best if I am honest about what I don’t know, rather than trying to maintain a facade of knowing everything.

A lot of teaching is improvising, so I’m familiar with that strategy. When I prove that I can handle an unplanned situation well just by improvising, it tells me maybe I’m more competent than I thought because I’m having to rely on previous knowledge I didn’t know I had.

Many referred to the connections between improvising as an instructor and their need to do so as an educational developer as well as its importance in a profession that requires broad knowledge and interaction with those from a wide variety of fields. Many pointed to improvisation as a skill that is learned and improved with time. We note that this “growth mindset” orientation toward improvisation may be an important idea for developers experiencing IP to espouse.

In addition to those coping mechanisms that we supplied on the survey (such as talking with people in your networks), respondents wrote about a host of other coping mechanisms they have used themselves. Exercise, meditation, relaxation breathing, yoga, and, more broadly, “self-care” were frequently mentioned. Some respondents indicated that they turn to prayer.

Self-care (exercise, hot baths, hobbies), family time, reminding myself that I can overcome challenges and succeed, recognizing the emotions and thoughts early on, and refraining from projecting out have all been helpful. A great therapist has been invaluable.

Exercise helps. It raises endorphins and gets my mind away from the fears.

I yell. In the dark. In a closet. (this is [hopefully] both funny and the truth)

Panic breaks. When I’m really freaking out, I put on my favorite song and allow myself to freak out until it’s over. Then I pull it together and do what I need to do.

Comments such as “panic breaks” and “I yell” suggest that acknowledging the strong feelings evoked by IP is important to these respondents as they cope with IP. Others extended such acknowledgment to intentional self-care in several aspects of their lives. Most comments in this category point to a combination of acknowledging the emotions of IP and tending to self-care as one experiences them.

Many specifically wrote, in their qualitative comments, that they over-prepare, over-work, over-achieve, or over-produce as a strategy for coping.

Over-prepare for every public activity.

I tend to over prepare and always have a contingency plan.

I over achieve and over produce. It’s beginning to bother the other chiefs in the company because, they have said, they can’t keep up with the level of production, but because I feel like I am starting in a hole, I have to fill that hole before I can actually get work done. This is not a good coping mechanism but it’s how I’ve done it up to this point.

The latter respondent explicitly indicates that this is “not a good coping mechanism,” which resonates with some of the concerns we noted with working harder as a consequence of IP. Indeed, there is some overlap between consequences and coping strategies. While clearly some experiences are consequences and not coping strategies (such as stress and anxiety), and vice versa, others (such as working harder) are more ambiguous and could easily fall into either category, depending on how the behavior is viewed or used by an individual.

It is helpful to note that Young (2011) distinguished between coping behaviors that alleviate IP and coping behaviors that keep people “safe” from harm by avoiding the shame and humiliation of being unmasked (p. 80). Young argued that working harder falls into the latter category. It does not actually help to make IP go away; rather, it just protects those who engage in that behavior from being discovered, which is the very (erroneous) fear of IP. While we did not ask respondents to categorize or comment on their coping strategies in this way, we encourage readers to focus on those behaviors that would help alleviate or eliminate IP rather than those that simply reiterate or reconfirm the false beliefs that IP is predicated upon.

Suggestions for Educational Developers Helping Others Cope with Impostor Phenomenon

Because of the high number of respondents who reported experiencing IP, and because of the number of academics who suffer from IP more generally, educational developers are in a unique position to leverage the experience of IP to relate to and support instructors. In workshops, consultations, and conversations, we have opportunities to name and normalize impostor feelings and offer suggestions to others for how to cope with them.

After reflection, healing, and vulnerability, an educational developer’s past or present experience with IP can become a great asset in connecting with colleagues or working with instructors who are in the throes of it themselves. Our hope is that a more thorough understanding of one’s own experiences and those of other practitioners will lead to opportunities for authentic connection and growth. To that end, we offer the following suggestions for leveraging one’s own IP experience when working with instructors:

- Bring up the phenomenon frequently and not just in dedicated programs; those who need to hear about it most may be the least aware of it or the least willing to show up at an IP-focused event.

- If you do hold a focused event or support group, choose the title of the program carefully to allow people to attend without fear of revealing their IP to those not attending.

- Spend time reflecting on your own experiences with the phenomenon. Think of a couple of examples or anecdotes from your own life that you feel safe sharing with a consultee or a group of workshop attendees.

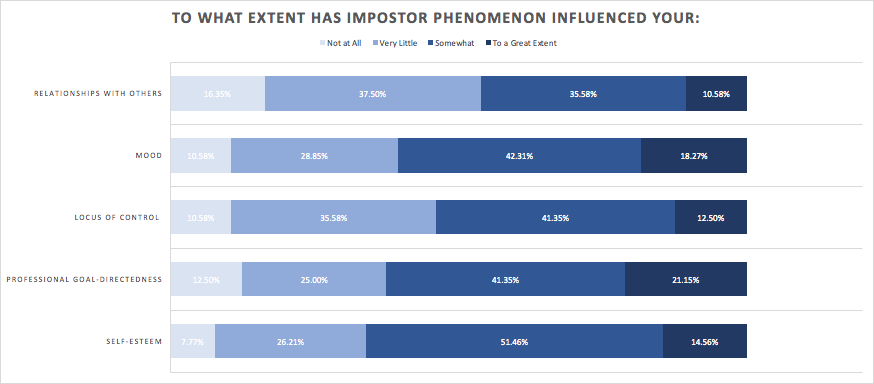

Educational developers report that they would recommend to faculty with whom they work the following coping mechanisms from a list provided on the survey: focusing on your strengths (64%), reviewing your experience and achievements (61%), talking with a safe person outside of your professional network (58%), talking with an adviser/mentor in your professional network (56%), and accepting that some tasks will not be done perfectly (53%). See Figure 3.

There are some small but interesting differences between Figures 2 and 3: that is, the coping mechanisms that respondents used themselves versus the coping mechanisms they might suggest to others. Most notably, the most commonly selected coping mechanism for themselves was accepting that some tasks will not be done perfectly (74%), whereas that was the fifth most common coping mechanism suggested to faculty (53%). It may be that it is still easier for respondents to focus on strengths in others (the most common coping mechanism suggested to faculty), while focusing more on their own moments of imperfection, perhaps as a result of IP.

When asked to describe any other coping mechanisms they might suggest to faculty, many respondents explicitly wrote that they would recommend the same strategies to colleagues that they themselves use. They reported suggesting the importance of being as prepared as possible (to which we add the caveat to avoid over-preparing, which only further contributes to IP); routinely seeking feedback; making time for reflection; practicing self-care (e.g., meditating, yoga); and finding supportive networks, which can provide reassurance to those afflicted with IP that they are not alone. Notably, respondents felt it was important to encourage a growth mindset around teaching in others (some mentioned Dweck’s [2007] work directly). Taken as a whole, responses in this section tracked closely with those in the previous section.

General Suggestions for Coping With Impostor Phenomenon

Additional strategies to cope with IP can be found in other literature. We include some here that seem relevant to educational developers and the constituents we are charged with supporting:

- Know the source. As Young (2011) suggested, “When you have an ‘impostor moment,’ it’s tremendously helpful to understand the possible reasons behind it. That’s because when you shift away from the personal it allows you to put your responses into perspective more quickly” (p. 27).

- Ignore the problem of other minds, as Revuluri (2018) put it. “You don’t know what other people are thinking about you.” We can make up stories, certainly, about what goes on in other people’s heads, but we can’t really know, and thus we shouldn’t spend too much time worrying about their (inherently inaccurate or incomplete) perceptions or trying to control for them.

- Related, critically examine the truth of the stories we tell ourselves. Katie (2002), for instance, encouraged readers to ask about troublesome thoughts: Is it true? Can you absolutely know it’s true? How do you react, what happens, when you believe that thought? Who would you be without the thought? Conducting fierce internal audits can shed light on mistaken perceptions or worries about exposure.

- Recognize the broader context. There are pernicious and insidious stereotype threats, social inequities, and structural barriers in higher education and beyond (Revuluri, 2018). What these mean, among other deleterious effects, is that you may end up feeling like an impostor due to environmental or situational factors that have nothing to do with you.

- Nevertheless, take deliberate counter-measures. As Jarrett (2017) said, “Soak up the self-doubt and then take the leap anyway. That’s what everyone else is doing.” In other words, heed the name of the popular book Feel the Fear…and Do It Anyway (Jeffers, 2006).

- Finally, practice self-compassion. Neff (2011) has discovered that self-compassion entails three core components: self-kindness, recognition of our common humanity, and mindfulness (p. 41). Cultivating each of these components can go a long way in helping to identify and move beyond IP.

Conclusion

Awareness of the troubling consequences of IP—including stress and anxiety, diminished self-esteem, not speaking up, slowed career trajectories, compulsion to overcompensate, and lowered quality of work—is crucial for the educational development field to grapple with the problem. We hope that the coping strategies presented in this article provide some additional ideas for those experiencing IP to minimize its effects.

We would also do well as a field to consider structural ways to address IP among our practitioners—for the well-being of everyone involved as well as for the good of the field. Rudenga and Gravett (2019) proposed:

Any educational developers can further increase awareness by sharing data and possibly personal experiences of IP with colleagues, being mindful of its prevalence particularly at new or transitional career stages or among certain demographic groups, while also being careful not to assume its existence in any individual. Center directors, in particular, could build regular considerations of IP into developmental opportunities and conversations with staff, ensuring that everyone is aware of its prevalence.

Here we add to that sentiment:

- Directors and leaders in the field would do well to educate themselves on the potential consequences of IP among educational developers, particularly in light of the ways that these consequences may reinforce existing structural inequities, and talk regularly with their staff about consequences as well as coping mechanisms for IP. Specific approaches to managing IP should be tailored to the specific individual staff, unit, and institution.

- Given both the prevalence of IP and the intensity of its negative consequences, a discussion of IP should be built into the annual POD Network conference and other events for new educational developers.

- All educational developers, regardless of their own experiences, should familiarize themselves with the symptoms, consequences, and effective coping mechanisms for IP to better support instructors and colleagues.

We conclude with two hopeful notes. First, several survey respondents noted that IP tends to diminish with time—and the accompanying experience and knowledge gained. One wrote that, in the survey, their “answers were in terms of the past…Since then impostor syndrome has been a distant memory.” This reflection may prove comforting to other educational developers who are in the throes of IP. Second, after reflection, healing, and vulnerability, an educational developer’s past or present experience with IP can become a great asset in connecting with colleagues or working with instructors who are in the midst of it themselves. Our hope is that a more thorough understanding of one’s own experiences and those of other practitioners will lead to opportunities for authentic connection and growth.

Biographies

Kristin J. Rudenga is Director of Teaching Excellence at Notre Dame Learning | Kaneb Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Notre Dame, where she also teaches neuroscience as an Associate Teaching Professor. She earned her PhD in Neuroscience from Yale University.

Emily O. Gravett is Assistant Director of the Teaching Area in the Center for Faculty Innovation and Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religion at James Madison University. She earned her BA from Colgate University in English and Religion and her MA and PhD in Religious Studies from the University of Virginia. She loves supporting the growth of her colleagues and feels continually inspired by their commitment to students, pedagogical innovation, and ongoing professional development.

References

- Aguilar, S. J. (2015, April 13). We are not impostors. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2015/04/13/essay-how-graduate-students-can-fight-impostor-syndrome

- Bahn, K. (2014, March 27). Faking it: Women, academia, and impostor syndrome. The Chronicle of Higher Education Community. https://community.chronicle.com/news/412-faking-it-women-academia-and-impostor-syndrome

- Brems, C., Baldwin, M. R., Davis, L., & Namyniuk, L. (1994). The imposter syndrome as related to teaching evaluations and advising relationships of university faculty members. The Journal of Higher Education, 65(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1994.11778489

- Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 15(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

- Clance, P.R., Dingman, D., Reviere, S.L., and Stober, D.R. (1995). Impostor phenomenon in an interpersonal/social context: Origins and treatment. Women & Therapy, 16(4): 79–96.

- Cokley, K., McClain, S., Enciso, A., & Martinez, M. (2013). An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(2), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00029

- Dancy, T. E., & Brown, M. C. (2011). The mentoring and induction of educators of color: Addressing the impostor syndrome in academe. Journal of School Leadership, 21(4), 607–634.

- Dweck, C. S. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine.

- Felder, R.M. (1998). Felder’s filosophy: Impostors everywhere. Chemical Engineering Education: 168–169.

- Gravois, J. (2007, November 9). You’re not fooling anyone. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/youre-not-fooling-anyone/

- Harvey, J. C., & Katz, C. (1985). If I’m so successful, why do I feel like a fake? The impostor phenomenon. St. Martin’s Press.

- Hochschild, A., with Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. Penguin.

- Huston, T. (2009). Teaching what you don’t know. Harvard University Press.

- Jarrett, C. (2017, January 13). How to beat the imposter syndrome feeling. 99U: A Creative Career Resource. https://99u.adobe.com/articles/54774/how-to-beat-the-imposter-syndrome-feeling

- Jeffers, S. (2006). Feel the fear…and do it anyway. Ballantine.

- Kaplan, K. (2009). Unmasking the impostor. Nature, 459: 468–469.

- Kasper, J. (2013, April 2). An academic with impostor syndrome. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/an-academic-with-impostor-syndrome/

- Katie, B., with Mitchell, S. (2002). Loving what is: Four questions that can change your life. Harmony.

- Keenan, C. (2016, October 20). Reclaiming authenticity. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2016/10/20/women-academic-leaders-and-impostor-syndrome-essay

- McElwee, R. O., & Yurak, T. J. (2010). The phenomenology of the impostor phenomenon. Individual Differences Research, 8(3), 184–197.

- Neff, K. (2011). Self-compassion: The proven power of being kind to yourself. HarperCollins.

- O’Meara, K., Terosky, A. L., & Neumann, A. (2008). Faculty careers and work lives: A professional growth perspective (ASHE Higher Education Report).Wiley.

- Parkman, K. (2016). The imposter phenomenon in higher education: Incidence and impact. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 16(1), 51–60.

- Revuluri, S. (2018, October 4). How to overcome impostor syndrome. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-overcome-impostor-syndrome/

- Rippeyoung, P. (2012, December 11). The imposter syndrome, or, as my mother told me: “Just because everyone else is an asshole, it doesn’t make you a fraud.” (A guest post). The Professor Is In. http://theprofessorisin.com/2012/12/11/the-imposter-syndrome-or-as-my-mother-told-me-just-because-everyone-else-is-an-asshole-it-doesnt-make-you-a-fraud-a-guest-post/

- Rudenga, K. J., & Gravett, E. O. (2019). Impostor phenomenon in educational developers. To Improve the Academy, 38(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20092

- Young, V. (2011). The secret thoughts of successful women: Why capable people suffer from the impostor syndrome and how to thrive in spite of it. Crown Business.