Impostor Phenomenon in Educational Developers

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

While impostor syndrome or impostor phenomenon (“IP”) is prevalent in higher education, with known negative effects, no study has yet investigated the experiences of IP among educational developers. After first reviewing prior research on the phenomenon, we use survey data to describe its frequency and manifestations within educational development. We identify factors and experiences that contribute to IP among educational developers, focusing on those that are distinct to the field. We conclude with suggestions for future research and broad recommendations for educational development as a field to tackle this problem.

Keywords: impostor phenomenon, impostor syndrome, educational developers, identity

Introduction

Impostor syndrome or impostor phenomenon (henceforth “IP”) leads its subjects to believe, often despite extensive evidence to the contrary, that they do not deserve the success or position they have achieved—often to deleterious effect. Traditional faculty members have been prolific in sharing their experiences of IP (e.g., Bahn, 2014; Gravois, 2007; Kasper, 2013; Keenan, 2016; Rippeyoung, 2012); graduate students have also written on the topic (e.g., Aguilar, 2015). As McMillan (2016) writes, “Many of the most respected academics in the world wake up every morning convinced that they are not worthy of their position, that they are faking it, and that they will soon be found out.” Yet these academics are not the only ones who experience IP. At a roundtable during the 2015 Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network annual conference about IP in our field, the room was filled with educational developers who related to the topic and who wanted to discuss their experiences with others (Rudenga & Gravett, 2015). A similar POD Network conference session a few years prior was also well attended (Bernhagen, Rohdieck, & Ross, 2012).

Attendance at these sessions suggests that educational developers may also feel like impostors, with emotions and experiences that resonate with previous descriptions, but with causes and manifestations distinct to our field. Yet no publications exist study this phenomenon in educational development—though, of course, articles about educational developer identity, more broadly, abound (e.g., Kinash & Wood, 2013). In this article, we take a step toward better understanding IP in this particular context, by presenting and contextualizing results from a national survey. We first provide an overview of IP and then consider its specific manifestations in the group of educational developers we surveyed. We report on the frequency of IP, its contributing factors, and the situations most likely to induce it among educational developers. We describe characteristics of the profession that may contribute to IP among practitioners and conclude with recommendations for alleviating some of its more systemic causes.

What Is Impostor Phenomenon?

The term “impostor phenomenon” was first introduced by Clance and Imes (1978). While it is colloquially referred to as “impostor syndrome,” it is called a “phenomenon” in more traditional literature because it is not recognized medically as a syndrome (Kaplan, 2009). The three main signs of IP, according to Harvey and Katz (1985), are: believing that one has fooled others into overestimating one’s own abilities; attributing personal success to factors other than one’s ability or intelligence, such as luck or an evaluator’s misjudgment; and fearing exposure as an impostor. As a result, IP can negatively impact an individual’s self esteem, professional goal directedness, locus of control, mood, and relationships with others (Brems, Baldwin, Davis, & Namyniuk, 1994).

Studies show that IP does not affect all groups equally. Many who experience IP share a common background, as described in Kaplan (2009): “Sufferers were often valued for their intelligence, giving rise to self doubts and feelings of fraudulence when excellent grades don’t materialize in graduate school and, later, when a new postdoc or new job isn’t a breeze” (p. 469). Early research (Matthews & Clance, 1985; Topping & Kimmel, 1985) also suggested that certain groups of people (i.e., high achievers, women, members of minority or underrepresented groups) and people in certain positions (i.e., graduate students, early career professionals, as well as those who have recently assumed a new job or a new career) were most susceptible to IP.

Although IP may most likely appear in individuals of particular demographic groups or career stages, it has also been described as “an affective experience that can arise in anyone in response to certain evocative situations” (McElwee & Yurak, 2010). Matthews and Clance (1985) found that many situational factors influenced the emergence of IP, including:

unexpected or unanticipated successes

early promotion

being the youngest person elected to a certain position

being over complimented/receiving indiscriminate praise

pressure to appear more confident than one truly feels

While the definition, symptoms, and contributing factors of IP have been well documented over the past four decades, no work has previously examined IP among educational developers.

Impostor Phenomenon among Educational Developers

Methods and Respondents

To explore IP within the context of educational development, we disseminated an IRB approved survey to the POD Network Google Group, a listserv for educational developers in the U.S. We captured ratings and short answers about IP among educational developers who responded to the survey, which revealed how many identified with IP as traditionally defined and which situations and aspects of identity provoke feelings of IP. We share both basic quantitative and qualitative results below; we provide examples of short answer responses to enrich and illuminate our findings. We have attempted to categorize and discuss recurring themes in respondents’ comments, though we recognize that these themes are, of course, closely intertwined.

In total, 156 educational developers responded to the survey. In some ways, our demographics resemble the membership of the POD Network (POD Network, 2016), the premiere professional organization for educational developers in the United States. Respondents mostly identified as women (76%, to POD’s 75%) and white (90%, to POD’s 86%). Our sample spans a range of years in the field: 34% of respondents had been involved in the field for 0 to 4 years and 32% for more than 10 years. Our sample may skew slightly toward more experience when compared to the POD Network, where 24% of members have been involved for 10 or more years and 56% for 0 to 5 years, although differences in survey options prevent exact comparison. Yet our sample skews younger than POD’s in age (respondents were mostly in their 30s and 40s, with the highest numbers in the 41 to 45 category, whereas POD members concentrate in their 40s and 50s). Slightly fewer of our respondents (68% to POD’s 76%) indicated that they held a doctorate.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study, which we wish to acknowledge at the outset. First, we sent the survey to only one educational development listserv, the POD Network Google Group, and thus cannot make certain claims about the field of educational development as a whole. Second, while our sample closely resembles POD’s demographics, the Google Group is not limited to the membership of POD, so we cannot make direct claims about IP in the POD Network. Third, our data are likely skewed toward those who have experienced IP, as educational developers who chose to take a survey on this subject may be the ones most likely affected by it. Finally, we note that while we describe data on the frequency of IP among survey respondents, we do not perform any inferential statistical analyses, given the limitations of our sample.

Overview of Results

The survey produced illuminating, and occasionally unsettling, results. Nearly all (96%) of the educational developers who responded to our survey reported experiencing IP at some point in their professional lives. Even if no other individuals experience IP in our field, besides those who responded to the survey, this number is substantial. Likely, however, this number is a floor, not a ceiling. Of the classical, three part definition of IP summarized above (Harvey & Katz, 1985), survey respondents most identified with “believing that one has fooled others into overestimating one’s own abilities,” with 77% reporting that they identify “somewhat” or “to a great extent.” Seventy two percent identify “somewhat” or “to a great extent” with “fearing exposure as an impostor” and 66% identify “somewhat” or “to a great extent” with “attributing personal success to factors other than one’s ability or intelligence.” It is notable that for each aspect of the classical definition, a majority of respondents identified with the experience, suggesting that IP in our field is multifaceted and, potentially, widespread (Figure 1).

Demographics

In accord with previous literature, our respondents indicated that there were a number of different (and, unfortunately, predictable) axes of identity to which they attributed their experiences of IP. Respondents believed their experiences were influenced by the following, with the parentheticals indicating the most commonly cited identity: gender (women), race/ethnicity (historically underrepresented minority), age (young), level of education (not having a Ph.D.), family educational history (first generation student), family class background (working/poor), and discipline (STEM):

I’m younger than most people in this field and my background isn’t in faculty development. It’s hard to tell faculty what they should be doing in the classroom when I don’t look much older than one of their students. Until very recently, I was still regularly mistaken for an undergrad.

I’m a black woman. I don’t know of any black female professional without some form of Impostor Phenomenon. Our credentials are actually called into question on a regular basis anyway. Of course we feel we aren’t qualified!

Personally, coming from a poor/working class background with plenty of family dysfunction and being a first gen college student are both key factors in where I think this phenomenon originates for me.

While some respondents simply attributed IP to general “demographics,” others pinpointed specific identities that contributed to their experiences of IP, such as “younger” or “first gen college student.” Moreover, many respondents listed multiple identities that influenced their experiences of IP, such as “I’m a black woman.” One respondent noted poor/working class background, family dysfunction, and being a first generation college student all as potential contributors to IP, without necessarily disentangling or deciding which was primarily responsible. All were, for that educational developer, “key factors.”

Many of the identities that respondents described—whether individually or in combination—are externally obvious and could easily lend themselves to the public exposure or judgment that those who suffer from IP fear. One respondent noted, for instance, that “I don’t look much older than one of their students” (our emphasis); thus one’s youthful appearance could give rise to questions about ability or intelligence. But other identities, like coming from a family with “plenty of dysfunction,” are invisible. They would not be able to provoke questions of competence or lead anyone to suspect fraudulence. Yet even these facets of identity provoke IP for the educational developers who are acutely aware that they possess them—and perhaps all the more so, as those individuals must work hard to keep these parts of themselves hidden.

The identification of certain demographics as contributors to IP may not be surprising in a field that, for instance, is not known for its racial/ethnic diversity (POD Network, 2016). It might be expected, unfortunately, for a black person to feel like an impostor in a profession that is overwhelmingly white. But the attribution of IP to gender and age is surprising, given that educational development, both nationally (Bernhagen & Gravett, 2017) and internationally (Green & Little, 2015), skews toward younger women early in their careers. That is, our respondents reported experiencing IP because of aspects of their identity that they, in fact, share with the majority of other professionals in our field. This is different than when feelings of IP are provoked for individuals who identify differently than the majority of their colleagues, such as women professors in STEM fields. What is especially notable in these responses is not necessarily the demographic data (as indicated, these attributes have been linked to IP in previous studies), but rather that, even in a field so committed to inclusion, collegiality, and diverse perspectives (POD, 2018), educational developers still attribute IP to specific, often marginalized aspects of their identity.

Past Experiences

In addition to various aspects of identity, we also know from the literature that an individual’s past experiences can contribute to IP. Our survey respondents mentioned non career related past experiences, such as bullying in youth, verbal abuse in a marriage, and parenting struggles, as contributors to IP on the job. Others wrote, in particular, about difficult experiences they had in graduate school:

I had a dissertation defense that DAMAGED MY SOUL. I’m not sure I’ve ever gotten over it.

For me, the feelings of being an imposter were magnified and entrenched through graduate school and I have carried this burden since.

Our results confirm that graduate school can evoke intense feelings of IP, as the abundance of advice columns for helping grad students cope (e.g., Hermann, 2016) also suggests. It may be that people who find success throughout their education with relative ease, but then encounter challenges in graduate school, are more prone to experience IP at that time (e.g., Kaplan, 2009). Yet respondent comments such as “I’m not sure I’ve ever gotten over it” or “I have carried this burden since” demonstrate that experiences of IP during graduate school do not necessarily resolve or disappear upon graduation, but may persist or become a struggle after transitioning into a full time career, even in educational development. These past experiences can become “entrenched” and difficult for the individual to move beyond. The use of ALL CAPS by one respondent, especially, underscores just how damaging this particular past experience can be.

Career Stage

Respondents’ impressions of the impact of their career stage on IP also supported previous findings. Many described training, early career, or transitional phases as times when they experienced IP most strongly, including being in graduate school, applying for new jobs, being new or early on in an educational development career, or being new to a particular job, therefore having a perceived lack of experience compared to those around them.

I think it is particularly prevalent when you are in a new position especially one where you have not done all the activities you would be responsible for. I have few feelings of imposter syndrome related to my work as a teaching consultant (I’ve done that before) by [sic] some of my other responsibilities are new and that is a challenge.

Mostly it arose early in my faculty development career when I was unsure how faculty from other disciplines would accept me. Now, it only happens when I am dealing with a group of resistant faculty from a particular discipline.

I’m new to being an educational developer full time…. I’m also new to the current institution I’m working in, and haven’t taught here. Finally, before coming to this new institution I consulted solely with graduate students, and am still learning to be comfortable working with faculty.

My identity as a graduate student who is near to graduating has had the biggest impact on my experience of Impostor Phenomenon even though I have been working full time in the Center.

It is well documented that IP is prevalent in early careers and during career transitions (Matthews & Clance, 1985; Topping & Kimmel, 1985), which our results support. We suspect that, because there are many routes into educational development, the career stages most vulnerable to IP may not be as clear cut as in traditional academic careers: while some developers who entered the field during or immediately following graduate school may experience IP due to their lack of tenure track experience or lack of teaching appointments, others who entered the field after years as a disciplinary faculty member may experience IP because they are venturing into a new field after decades focused on a different one.

Respondents also wrote about the complications of being in graduate school while working full time in their university’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) or of working in a CTL where they had previously worked or sought help as graduate students. As has previously been described (Kaplan, 2009; Matthews & Clance, 1985), graduate school is a common time for IP to run rampant, so it is unsurprising that remaining in the environment where one attended graduate school, or overlapping that experience with the early years of a new career, would lead to IP.

An additional theme that arose was that some educational developers were quite comfortable and did not experience IP while working with graduate students, but that transitioning to working with faculty brought on feelings of IP. Since a subset of educational developers do work with graduate students (whether as graduate students themselves or in their first full time job), it is worth noting that such a career transition may well resurface IP.

Finally, we wish to highlight here the differences between IP and a healthy awareness of the areas in which one still has much to learn. Certainly it is reasonable and even beneficial to be aware that, as a newcomer, one may have less knowledge of a field than someone with years of experience. Moreover, routine self examination paired with a growth mindset (Dweck, 2007) can foster professional growth, new opportunities, and fresh connections. If, however, that newcomer feels that she has fooled a hiring committee or been hired merely out of luck and fears exposure as an unqualified fraud, then such feelings would be described as IP. Many respondents described the latter, experiencing insecurities seemingly out of proportion with their achievements and past record.

Day to Day Tasks

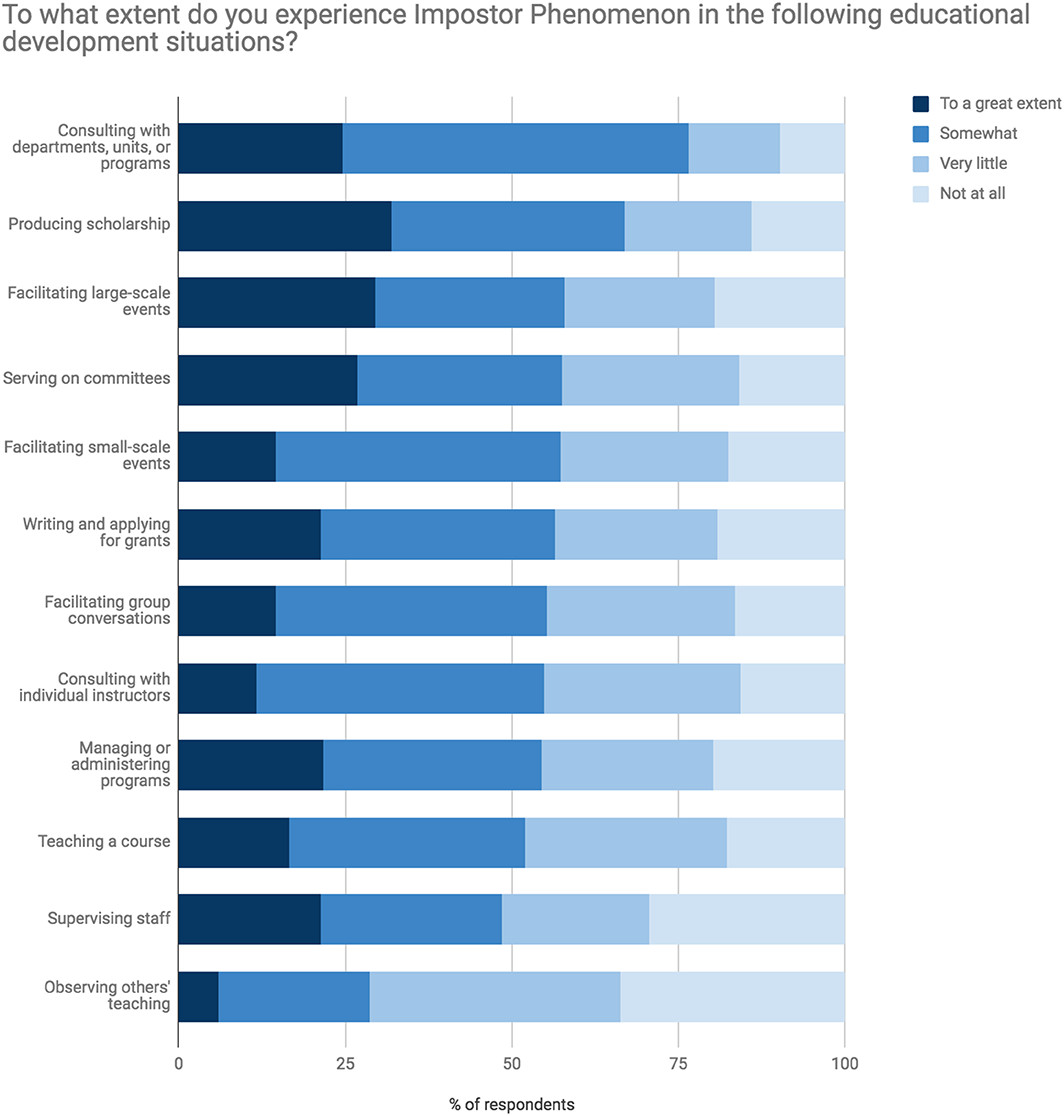

While career stage is clearly an important variable in IP experience, we also sought to understand the relevance and impact of different day to day tasks. When responding to a list of common daily activities for educational developers (some of which overlap with duties of other academics), respondents most frequently reported experiencing IP “somewhat” or “to a great extent” when consulting with departments, units, or programs (76%) and producing scholarship (67%). Respondents also report experiencing IP “somewhat” or “to a great extent” when serving on committees (57%), writing grants (57%), facilitating large scale events such as full day orientations or institutes (58%), facilitating group conversations (55%), consulting with individuals (55%), managing or administering programs (54%), teaching (52%), and supervising staff (48%; though many of our respondents may not supervise staff in their current roles). The least IP inducing situation was observing others teaching, though 29% still experienced IP then. We suspect that observing others teaching is less IP inducing than other situations because the educational developer is typically not being judged in that scenario. In sum, for most of the daily job duties common in our field, over 50% of respondents report experiencing IP. These results emphasize that the experience of IP is not limited to large events or significant milestones, but can be pervasive throughout the daily life of an educational developer.

When the data are broken down further, the common activities in which respondents most frequently reported experiencing IP “to a great extent” were producing scholarship (32%) and facilitating large scale events for faculty (29%). Qualitative data from other portions of the survey suggest that large scale events may induce IP so strongly because they involve a large audience of people who are potentially judging the facilitator’s competence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impostor Phenomenon in Common Educational Development SituationsLegend: 156 Educational developers reported the extent to which they experience impostor phenomenon in several common educational development situations.

Figure 2. Impostor Phenomenon in Common Educational Development SituationsLegend: 156 Educational developers reported the extent to which they experience impostor phenomenon in several common educational development situations.Many respondents emphasized in their comments that they experienced IP in scholarly endeavors, ranging from writing and submitting papers to presenting at conferences:

I feel uneasy when I and/or others are talking about “the literature on teaching and learning,” and/or the “learning sciences.” What contributes to this is that I haven’t had the time, or made the time, to develop much of my own research practice, or even to stay very current on reading what others have done.

The fact that most of us are essentially switching disciplines when we move into this field. And, for many of us, we aren’t given the requisite time to gain the level of expertise in SoTL that we have in our home discipline. So we’re acutely aware that we aren’t experts in the same way. I think that those who didn’t get a PhD may be less bothered by the sort of informal expertise one gains by doing the work. But those of us with PhDs know what it means to be an expert in the literature, so we’re aware of our shortcomings.

While other academics may also find that scholarship contributes to IP, we suggest that these situations can especially induce IP in educational developers because an active scholarly agenda may be outside of or an add on to their job description, and/or because the scholarship of educational development or the scholarship of teaching and learning research methods and genres may fall far afield from the discipline in which they were originally trained. Comments revealed that many educational developers expect themselves to have the same depth and breadth of familiarity with the SoTL (both disciplinary and general) and educational development literature as they have with the literature in their original discipline. While some familiarity with research in the field is certainly foundational to working as an educational developer, survey responses suggest a mismatch between some educational developers’ expectations of themselves and the level of knowledge needed for providing support for instructors.

Other themes that emerged from respondents’ descriptions of IP inducing work situations aligned with previously published data on IP, emphasizing the impact of visibility, novelty, and competition. Respondents reported experiencing IP when doing highly visible organizational development work on campus (for example, serving on major task forces or leading strategic initiatives) and work visible beyond campus (for example, being interviewed by the media or creating online content) or when interacting with those in positions of power such as deans or provosts. Respondents also listed trying something new for the first time (for example, planning a major event, developing an orientation, or writing an assessment plan) as a time of increased IP.

Educational Development as a Field

A major goal of this study was to extend previous research on IP to the educational development field and to understand ways in which it manifests distinctly from other areas of academe. We found that the field is perceived as inclusive and welcoming, but that interactions with colleagues can nonetheless provoke IP. We go on to describe the impact of the lack of official educational development credentials, the perception of ours as a “cop out field,” the poor treatment of educational developers in the institutional hierarchy, and the frequent introduction or positioning of educational developers as experts. Here, we describe these elements of the field, which emerged from respondents’ comments and seem to especially exacerbate their experience of IP.

Despite the high level of IP among educational developers reported here, some respondents posited that the inclusive, welcoming nature of the educational development field might make it a less likely place to develop IP vs. traditional academic careers, or reported that they themselves have experienced less IP since switching out of their original field and into educational development.

I think that educational developers are largely an inclusive and welcoming group who are more likely to recognize each other’s skills and accomplishments than to highlight others’ weaknesses.

They genuinely care about helping people teach better, and they act as a “guide on the side” so their ego is not at the forefront of the issue. It is okay for them to be genuine and not have to inflate themselves.

At least, we all laugh about our IP together at particular times (like a bizarre department consultation request or committee presentation) and this normalizes slight anxiety and discomfort. It’s a part of the job.

Respondents described experiencing in educational development a freedom to be authentic or “genuine,” without having to constantly present falsely inflated or aggrandized versions of themselves. Colleagues in the field are perceived to be inclusive, focused on accomplishments and successes, versus weaknesses, likely due to the field’s commitment to growth. And there is a strong sense that we are all, inevitably, experiencing IP together, which can reduce its shame or sting.

However, many respondents described situations when they interacted with other educational developers, such as at the annual POD Network conference, as likely to induce IP:

I often experience this at conferences. Everyone seems so intelligent. Even the grad students seem to know more about the field than I do!

When I am with other educational developers with significant experience and strong academic pedigree, I feel like I don’t belong and have nothing to contribute.

When I was around colleagues who were clearly more competent than I am. It didn’t matter that they had 20 years in the field to my 2, logic has little influence in fear. Don’t get me wrong, they were wonderfully kind and accepting, but I was clearly sitting at the adult table when I belonged at the kiddie table.

It is worth noting that most of the respondents describing IP at educational development conferences did so because they felt awed by smart and accomplished colleagues, rather than because they felt patronized, belittled, or dismissed. Despite this distinction, and despite the fact that many respondents elsewhere described educational development as a welcoming, open environment less cutthroat than traditional academia, this finding reminds us that we as a field are not immune from inadvertently inducing IP in our colleagues.

Many respondents described the lack of available training and credentials for becoming an educational developer.

People come to educational development from a variety of fields, none of which are formal training in educational development. When we don’t have formal training in an area, we perhaps never feel like an expert in that area. We recognize that we know more about a different area (our PhD discipline) than we do about educational development.

Working outside of the discipline you have been trained in (for most of us) means that you aren’t an expert in the thing that you are doing (or that you’ve learned on the job) on the one hand, and that you are no longer an expert in your field, often, because of how you spend your time.

I attribute my experiences with the impostor phenomenon to the fact that educational development is not my original field…. Since I am learning on the job, instead of undergoing training in graduate school, I feel like my claim to expertise is thinner than it is in my original field.

There is no direct path to educational development, so often people have a degree in an education field or sometimes a completely unrelated field. I think this affects new EDs [educational developers] the most as they begin to form their identity as an ED.

Educational development is a field made up of practitioners and degree holders from a wide range of disciplines and several disparate career trajectories. There is no single expected or required training program analogous to the disciplinary Ph.D. for professors, and no available, widely respected credential in educational development (Abbot & Gravett, 2018). Such a range of possible entry points adds a rich array of knowledge and backgrounds to our field, but it also means that there are no available means to be officially declared an expert, or even “certified.” Therefore, practitioners cannot, for example, mitigate IP by reminding themselves that they earned an educational development degree with honors. We are not necessarily advocating for the creation of degree programs in educational development, but simply noting that the lack of them may leave practitioners feeling unqualified and prone to IP.

Another notable theme that emerged was a perception of educational development as a “copout field” for those who are not “real academics.”

Many of us worry that faculty assume we have "failed" because we didn’t pursue tenure track positions, left them by choice, or didn’t get tenure.

We are not "real" academics even those of us who have been academically trained.

I was not a full time faculty member before I became an educational developer. I worry about how others view my credibility as a result. My age and career stage have been directly called out in some circumstances, causing me to be more sensitive to them even in situations when they are not called out.

Several respondents report perceiving the belief among the instructors with whom they work that they went into educational development because they could not get or keep a tenure track position. In some cases, this may be true, but even those who pursued educational development as a first choice career are not immune from such perceptions. In any case, the culture of academia clearly sets up tenure track jobs as the gold standard, with alt ac and other career tracks often viewed as consolation prizes for the unsuccessful. Thus, even those who intentionally chose educational development—whether before or after tenure track employment—can feel or be made to feel that they have failed, settled, or taken the easy way out.

Another experience commonly cited among survey respondents was being snubbed or treated poorly in the institutional hierarchy:

Being a staff member can hinder confidence in consulting with faculty members. In the hierarchical structure of academic, it is often the case that faculty look down upon staff as less intelligent.

What brings it back is the faculty that treat me as a second class citizen at the university.

I have a terminal degree in my field but it is not a PhD. This sometimes means that I am concerned in my interactions with PhDs that I will be seen as not good enough to do the work I am doing.

Because my full time work is a staff position in our teaching center, I am treated and seen as staff by faculty. So, being a staff member in this work contributes to my feelings of being an imposter, or at least being seeing [sic] as one. On our campus, our provost publicly, unapologetically, and frequently says, “Faculty are first. We would not be a world class institution without our faculty. Students are second and the reason staff are here is to support our students and faculty. Faculty will say things like, “Well, as a ‘real’ faculty member, I think….” In some circumstances I have to spend time establishing my credibility…. I relish the times when I work with faculty who see my [sic] as an equal partner.”

Many educational developers are hired as staff, straight out of graduate school or without a doctoral degree. They do not always have a teaching appointment or routine teaching duties. Yet these same educational developers may be tasked with assisting full time, tenured, or tenure track faculty members. This situation, some respondents reported, can lead to being doubted or even disdained as “second class” citizens. There is a clear hierarchy on college campuses, from their perspective, and the sometimes low or unclear positions of educational developers—especially when they must be in regular contact with those in seemingly more powerful positions—can provoke feelings of IP, as others look down upon them.

Finally, despite perceptions of joining a “copout” field or of occupying a tenuous position within the institutional hierarchy, educational developers are frequently introduced, positioned, or viewed as experts on teaching, expected to share advice and expertise with instructors.

First, many are classified as staff, which in the hierarchical structure of academia, creates a dynamic that places the developer below the faculty member. This can be a difficult power relationship to navigate, as at the same time you are placed in the position of giving advice, or of being an "expert" in certain pedagogical areas.

Any time I am expected to be the leader and/or “know it all,” such as chairing a committee, facilitating a book group, giving a presentation, etc.

Because we are seen as the “experts” in all things teaching and learning, it’s risky to admit when there is not an easy or set answer to a question. There are also risks when working with faculty from STEM or "professional disciplines" for those of us with backgrounds in humanities and the perception that we are "touchy feely" and have a less rigorous creative process.

Instructors often look to you to provide all the answers or magic “pills” in pedagogy related issues. This places a lot of pressure on me, as I feel like I have to have the “right” answer for everything. But my internal dialogue tells me I actually know nothing about anything. It can be paralyzing because I am constantly questioning what I say as I am saying it…. Participants look to you as an “expert” when I never see myself as an “expert.”

Conflicting messages about credibility and status can be disconcerting and may be exacerbated by all that educational developers are expected to know and the wide range of disciplines that they are asked to navigate. The reality is that educational developers cannot be experts in all things pedagogical. The literature and practice are simply too vast and it is impossible to know everything. Yet, as respondents pointed out, instructors and other stakeholders often expect educational developers to “know it all” or to be able to offer “magic” fixes. These expectations can interact with the aforementioned lack of formal training or credentials available for educational developers, as well as the frequent lack of recent first hand teaching experience, creating dissonance for both the educational developer and the instructors with whom they work.

These scenarios, while new to the IP literature, are in many ways consonant with previous studies about educational development. First, the profession has been acknowledged as “liminal” and “betwixt and between” (e.g., Little & Green, 2012); educational developers have even claimed that they “don’t think that educational/academic development is a field in its own right in a cognitive sense yet” (Harland & Staniforth, 2008, p. 675). This tenuousness may leave many educational developers feeling unsettled and insecure about their positions and the value of the profession writ large. Second, educational developers usually come to the field after training, specializing, and attaining an advanced degree in another field or discipline (Green & Little, 2015). As Harland and Staniforth (2008) conclude, “It seems that all developers must come from ‘somewhere else’” (675). This may make some of us feel never quite at home in the profession we now inhabit. Third, researchers such as Harland and Staniforth (2008) have uncovered “the contested nature of academic developers’ knowledge”: one of their own survey respondents indicated that “we do not have a shared and agreed set of foundational knowledge… we are an interdisciplinary field of practice and there isn’t even a large body of accounts of that practice, let alone theorising or historicising or sociologising of that practice” (675). Without an accepted body of knowledge that we all share, it may be difficult to work from a place of confidence. Finally, we tend to wear many hats and may have to nimbly assume a number of different roles in our educational development work (Bernhagen & Gravett, 2017; Land, 2000), practicing what Carew, Lefoe, Bell, and Armour (2008) term “elastic practice.” This means that we may frequently find ourselves in new situations, trying to do things for the first time. These studies of educational development align very closely with our findings; here we add evidence that one consequence of these aspects of the profession may be a pervasive experience of IP among its practitioners.

Implications for Future Research

The above results describe the prevalence and manifestations of IP among a sample of educational developers, an important step toward understanding and describing this issue. Brems et al.’s (1994) description of IP’s impacts on self esteem, professional goal directedness, locus of control, mood, and relationships with others suggests that its consequences may be many, varied, and severe. Additional research is needed to further document these consequences within educational development. Further studies describing common and effective coping mechanisms for IP would benefit both educational developers and the instructors we serve. Finally, our survey results hinted at the importance of intersectionality in the experience of IP; more focused study would help to fully explore the roles of intersecting identities in IP.

Conclusion

Our survey results both confirm and extend previous findings about IP, which suggest that it is pervasive throughout the academy, to show that it is a common experience among educational developers as well. In a sample of 156 educational developers, over 96% of respondents reported experiencing IP in their professional lives. Respondents provided insights into the demographic factors and career stages that most induced IP, in ways that largely coincided with what was already known about IP. We found that, in nearly every aspect of the day to day work of an educational developer, at least half of respondents reported experiencing IP, with especially strong experiences during large scale or public events and scholarly endeavors. Furthermore, many described conferences and interactions with other educational developers—despite the field’s reputation for inclusion and kindness—as IP inducing. Finally, many respondents described aspects of educational development as a field that present particular risks for IP, including the lack of formal credentials or training, the view of educational development as a copout field, poor perceptions or even poor treatment within the hierarchies of their institutions, and being asked to serve as an expert in areas in which they may have little or no formal training. Taken as a whole, these data paint a vivid picture of the origins and state of IP among educational developers.

Looked at from a broad perspective, the current findings suggest ways that educational development as a field could improve the experience and effectiveness of its professionals by mitigating the effects of IP:

Add a disciplinary teaching component to educational development job descriptions to improve the confidence and credibility of educational developers. Center directors and those in other positions of influence over job descriptions should consider the significant benefits that a small disciplinary teaching load (for example, one class per year) would reap for the educational developer’s own experience, expertise, and mindset as well as for credibility among instructors.

Expand guidance and support for scholarship in educational development venues to demystify and improve the experience of what is for many educational developers the most IP inducing element of their work. We suggest building on the success of POD Network conference workshops on publishing in the field with periodic teleconference workshops offering similar or expanded content to those who may not be able to attend in person (such as those that have been recently offered by the POD Scholarship Committee); with cross institutional online writing groups or in person writing retreats for educational developers pursuing scholarship; and with explicit mentorship for new scholars joining the field, either within a center or across the POD Network.

Increase awareness of the pervasiveness of IP, to normalize the experience and to encourage empathy for our colleagues and the instructors with whom we work. The POD Network’s support of IP focused conference sessions is an important step in this direction. Educational developers can further increase awareness by sharing data and possibly personal experiences of IP with colleagues, being mindful of its prevalence particularly at new or transitional career stages or among certain demographic groups, while also being careful not to assume its existence in any individual. Center directors, in particular, could build regular considerations of IP into developmental opportunities and conversations with staff, ensuring that everyone is aware of its prevalence.

Most importantly, educational developers who experience IP should be reassured that they are far from alone, and remember that others they interact with—despite our profession’s efforts at inclusion—may be silently experiencing the same feelings.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the vulnerability and insights of those who participated in our survey, as well as those who attended the 2015 POD Network conference roundtable on this topic.

References

- Abbot, S., & Gravett, E.O. (2018). Querying the P(hD)ath to educational development in higher education. In C. Bossu, & N. Brown (Eds.), Professional and support staff in higher education. Singapore: Springer.

- Aguilar, S.J. (2015, April 15). We are not impostors. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2015/04/13/essay how graduate students can fight impostor syndrome.

- Bahn, K. (2014, March 27). Faking it: Women, academia, and impostor syndrome. Chronicle Vitae. https://chroniclevitae.com/news/412%C2%ADfaking%C2%ADit%C2%ADwomen%C2%ADacademia%C2%ADand%C2%ADimpostor%C2%ADsyndrome.

- Bernhagen, L., & Gravett, E.O. (2017). Educational development as pink collar labor: Implications and recommendations. To Improve the Academy, 36(1), 9–19.

- Bernhagen, L., Rohdieck, S., & Ross, S.M. (2012). The developing developer: Constructing self images that reflect our competence. In 37th Annual professional and organizational development network in higher education conference. Seattle, WA.

- Brems, C., Baldwin, M.R., Davis, L., & Namyniuk, L. (1994). The imposter syndrome as related to teaching evaluations and advising relationships of university faculty members. The Journal of Higher Education, 65(2), 183–193.

- Carew, A., Lefoe, G. E., Bell, M., & Armour, L. (2008). Elastic practice in academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 13(1), 51–66.

- Clance, P., & Imes, S. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice, 15(3), 1–8.

- Dweck, C. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Ballantine.

- Gravois, J. (2007, November 9). You’re not fooling anyone. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Green, D.A., & Little, D. (2015). Family portrait: A profile of educational developers around the world. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(2), 135–150.

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2008). A family of strangers: The fragmented nature of academic development. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 669–678.

- Harvey, J.C., & Katz, C. (1985). If I’m so successful, why do I feel like a fake? The impostor phenomenon. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Hermann, R. (2016, November 2016). Impostor syndrome is definitely a thing. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Impostor Syndrome Is/238418

- Kaplan, K. (2009). Unmasking the impostor. Nature, 459(21), 468–469.

- Kasper, J. (2013, April 2). An academic with imposter syndrome. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Keenan, C. (2016, October 20). Reclaiming authenticity. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2016/10/20/women academic leaders and impostor syndrome essay#.WAszTDMIINY.mailto.

- Kinash, S., & Wood, K. (2013). Academic developer identity: How we know who we are. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(2), 178–189.

- Land, R. (2000). Orientations to educational development. Educational Developments, 1(2), 18–23.

- Little, D., & Green, D. (2012). Betwixt and between: Academic developers in the margins. International Journal for Academic Development, 17(3), 203–215.

- Matthews, G., & Clance, P.R. (1985). Treatment of the impostor phenomenon in psychotherapy clients. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 3(1), 71–81.

- McElwee, R.O., & Yurak, T.J. (2010). The phenomenology of the impostor phenomenon. Individual Differences Research, 8(3), 184–197.

- McMillan, B. (2016, April 18). Think like an impostor, and you’ll go far in academia. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/think impostor and youll go far academia

- POD (2018). Strategic plan and mission. http://podnetwork.org/about us/mission/.

- POD Network (2016). The 2016 POD network membership survey: Past, present, and future. http://podnetwork.org/2016 membership survey report/.

- Rippeyoung, P. (2012, December 11). The imposter syndrome, or, as my mother told me: “Just because everyone else is an asshole, it doesn’t make you a fraud.” (A guest post). The Professor Is In.

- Rudenga, K., & Gravett, E.O. (2015). Impostor syndrome: Reflecting on our experiences to better serve instructors. In Roundtable conducted at the 2015 POD network conference. San Francisco, CA.

- Topping, M.E.H., & Kimmel, E.B. (1985). The impostor phenomenon: Feeling phony. Academic Psychology Bulletin, 7, 213–226.