Connect, Change, and Conserve: Building a Virtual Center for Teaching Excellence

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

In an era of limited fiscal and human resources, educational developers are seeking innovative ways to connect with their constituents. Developing a “virtual” center for teaching and learning (CTL) is one approach to consolidating development resources and reaching busy full time and adjunct faculty. This article will describe the process used to create and sustain a Virtual Center for Teaching Excellence (vCTE) at a diverse, mid sized university campus. This process required connection between departmental faculty developers and stakeholders, change of the campus mindset, and conservation of resources through shared efforts. Challenges faced and recommendations to overcome those challenges will be presented.

Keywords: faculty development, teaching and learning, online learning, virtual center for teaching and learning

At a time when institutions are challenged to do more with less, educational developers are seeking innovative ways to connect with their constituents. Developing a “virtual” center for teaching and learning (CTL) is one approach to consolidating development resources and reaching busy full time and adjunct faculty. The purpose of this article is to describe how a virtual center was created at Creighton University, a diverse, mid sized university campus with no centralized educational development office and no physical CTL. We will provide readers with a review of the literature on developing a virtual center, a description of the process used to build and sustain a virtual center at Creighton University, and a discussion of challenges and recommendations for those considering a similar endeavor. This process required connection between departmental faculty developers and stakeholders, change of the campus mindset, and conservation of resources through shared efforts. Challenges faced and recommendations to overcome those challenges will be presented.

Background

Educational development is at a critical juncture in its evolution as a discipline. While the field has experienced tremendous growth since the 1960s, today’s increased focus on fiscal responsibility has forced some institutions to scale back on development budgets and, in some cases, eliminate existing CTLs (Frantz, Beebe, Horvath, Canales, & Swee, 2005; Schroeder, 2011).

This decreased availability of resources is occurring simultaneously, with changes in higher education that have created an increased need for educational development. Today’s climate of heightened accountability for student learning outcomes necessitates that faculty use evidence based pedagogical methods coupled with rigorous assessment strategies (Schroeder, 2011). Rapid technological advances and the growth of online learning demand that faculty adapt their pedagogical approach and stay abreast of changes in learning management systems. An increasingly diverse student population requires an understanding of the principles of androgogy and the unique needs of the adult learner (Cercone, 2008). Finally, the growing use of adjunct faculty in brick and mortar as well as online classrooms creates the need for “just in time” programming that can be accessed “anytime, anywhere” (Burns, 2013, p. 16; Shea, Sherer, & Kristensen, 2002, p. 163). This changing landscape calls for the development of new models, a shift in the delivery of educational development programming, and a transformation of the discipline itself (Austin & Sorcinelli, 2013).

While institutions with established CTLs are best positioned to adapt to such changes, universities without a centralized educational development department may struggle to meet the needs of their faculty in the face of so many challenges. This article will describe how Creighton University, a private, Catholic, Jesuit institution in the Midwest, responded to these challenges by creating a “virtual” CTL. Creighton University defines a virtual CTL as a robust website that provides online access to an institution’s educational development resources. These resources may include text documents describing pedagogical strategies, faculty orientation information, video media, and interactive spaces.

Literature Review

Getting Started: Connect

A literature search of the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) database using combinations of the terms teaching and learning, teaching excellence, virtual, online, center(s) and centre(s) reveals a paucity of literature to guide the development of a virtual center. However, even though few publications exist that are specific to the virtual medium, the educational development literature is replete with best practices for developing effective CTLs (Frantz et al., 2005; Hanover Research, 2014; Sorcinelli, 2002). These provide a useful starting point for the planning of a virtual center.

From the outset, it is critical to identify and seek input from key stakeholders. Schumann, Peters, and Olsen (2013) describe a process for “co creating value” in the design of a CTL by establishing a collaborative culture that welcomes input from administrators, faculty, students, staff, and even consumers during the early planning stages for a center. Input from stakeholders can be used to craft a mission statement that aligns well with the mission and needs of the institution (Schumann et al., 2013; Shea et al., 2002).

Garnering input from key stakeholders may translate into administrative and faculty support for the endeavor. Sorcinelli (2002) recommends seeking and securing this early on by emphasizing faculty involvement and “listening to all perspectives” (p. 10). Faculty support is critical as faculty are ultimately the consumers of services provided by a center and can serve as future champions of a center (Frantz et al., 2005; Schumann et al., 2013). Administrative support is ultimately necessary for sustainability and future allocation of resources. Schroeder (2011) and Sorcinelli (2002) recommend working with administrators at the highest levels in order to ensure that educational development is embedded within the strategic plan and organizational structure. Frantz et al. (2005) suggest that this can be accomplished by developing goals in collaboration with administrators as well as systematic ways to assess these goals. When an individual is chosen to lead a center, the preferred reporting structure to ensure ongoing administrative support is a direct reporting line to the Provost or Vice President for Academic Affairs (Frantz et al., 2005). Solidifying the center’s position in this manner may prevent educational development and the CTL itself from being pushed to the “margins” or “basement” in terms of institutional priorities (Schroeder, 2011, p. 13; Van Note Chism, 1998, p. 141). Garnering support from key stakeholders can be accomplished by forming advisory boards and surveying faculty, students, and staff regarding the development needs of the institution (Schumann et al., 2013).

Once the support of stakeholders is ensured, feedback from these groups can be used to identify key functions of the CTL. According to Hanover Research (2014, educational development programs generally utilize workshops and seminars, mentoring programs, faculty learning communities, and technology support to meet faculty needs. Specific services provided often include new faculty orientation, classroom observations, grant management, and coordination of teaching awards (Hanover Research, 2012). While such centers generally focus on improving teaching and learning, they may also work with assessment offices, instructional technology departments, and even campus based writing centers (Austin & Sorcinelli, 2013). Additional functions include faculty networking opportunities, individual consultation, and grant writing assistance (Frantz et al., 2005).

Building a Virtual Center: Change

Creating a virtual CTL in the absence of resources for a physical center requires a change in mindset. While the organizational and procedural principles described above still apply, much of the development phase for a virtual center will focus on issues related to technology, access, and development of content rather than staffing, program planning, and location and design of physical space. Benefits of utilizing a “virtual” approach include a short set up time and the ability to utilize the teaching expertise of faculty in a variety of disciplines (Bryan, Cressman, & Diemer, 2010).

Bryan et al. (2010) recommend creating a virtual teaching and learning center in two phases: assessment of resources and building. During the assessment phase, key activities include identifying the target audience, available resources, challenges and resource gaps, and the virtual medium. The building phase consists of identifying content and content experts/authors. It also involves assessing the success of the center and developing plans to sustain it.

The assessment phase as described by Bryan et al. (2010) closely parallels the process described above for identifying stakeholders, seeking input, and positioning the virtual center strategically within the institution. A unique aspect of planning a virtual center, however, is selecting a virtual medium. Because the virtual medium is the sole means of delivering content to users, the process can be equated to developing the blueprints for creating an inviting space and convenient location for a physical teaching center. For this reason, close collaboration with an information technology office and campus libraries is critical to ensure a user friendly experience as well as a design consistent with the University’s branding and existing web presence. Partnering with these entities early in the development process can also increase both the academic and technical resources available to users (Sherer, Shea, & Kristensen, 2003; Shea et al., 2002; Weiss & Enyeart, 2009).

Neal and Peed Neal (2010) recommend designing a “simple, uncluttered and functional” (p. 110) site by avoiding dropdown menus, providing navigation bars with clear paths back to the homepage, and using dark text colors on light backgrounds for easy reading. In order to decrease page downloading time, they recommend limiting PDF files to only those documents meant to be printed by users rather than content intended to be read online. They also suggest avoiding animation, moving images, and complex graphics, which can be distracting and increase loading time. A prominent link on the university’s faculty and staff homepage provides easy navigation and sends a message regarding the importance of educational development importance within the institution’s organizational structure.

All virtual center websites should be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to ensure that the site is fully accessible for all users. This can be accomplished by working closely with a campus Office of Disability Accommodations. Basic accessibility features include compatibility with text to speech software and audio descriptions of images for those with visual impairments. In addition, captions or transcripts should be available for those with hearing impairments, aural processing disabilities, and English language learners. The US Department of Health and Human Services provides accessibility checklists for Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint as well as HTML, multimedia, and Adobe Acrobat files (US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

The building phase, as described by Bryan et al. (2010), can be compared with selecting a physical center’s staff and planning development workshops; however, for a virtual center, most content will be available to users as textual information and videos. The primary activity during this phase is determining the content to be included on the site and identifying authors who can develop and present the content in an engaging manner.

While most universities may be able to identify multiple pedagogical content experts to build the site, a major challenge in this area is the issue of time constraints and multiple demands on potential faculty authors. As the site is being built, temporary links to external resources, such as The Teaching Professor publications, Merlot, the TLT group, and other CTLs that authorize sharing of content, can be provided to users (MacDonald, 2009; Neal & Peed Neal, 2010).

Macdonald (2009) suggests utilizing faculty as content experts to share pedagogical information on the site and mentor others through online user groups. This approach can help increase buy in by creating a feeling of ownership in the site and fostering the development of a “community of practice” model. According to Sherer et al. (2003), well designed educational development portals can provide “internet enhanced” (p. 188) communities of practice that offer both synchronous and asynchronous access to library resources, best practices in teaching, and access to the expertise of colleagues both inside and outside the institution. Linking to a variety of campus resources, such as a writing center, information technology department, or a library, is a way to build partnerships with stakeholders and establish the virtual center as a portal to the university’s development resources (Neal & Peed Neal, 2010; Weiss & Enyeart, 2009).

Content placed on a virtual center should provide users with examples of use of evidence based, online pedagogical principles. As such, content delivery should not be limited to passive methods such as text and video. Interactive, learner centered instruction and resources that help build an online learning community should be integrated into the virtual center’s design. Burns (2013) suggests that the future of professional development lies in harnessing the power of social networking to create “personal learning networks” (p. 17) where teachers can join chat groups, collaborate, blog, and share resources. A virtual CTL provides a rich opportunity to create such a network.

Sustainability: Conserve

Finally, plans for marketing and sustainability in the building phase call for long term thinking and conservation of resources. Low cost marketing can be accomplished via mass emails with links to the virtual center, limited print brochures, and the use of announcements through university faculty publications and faculty meetings (Weiss & Enyeart, 2009). Sustainability efforts should include developing a network of stakeholders willing to periodically review the site and develop content. Sustainability should also include an assessment plan based on analysis of website traffic. A variety of low cost and free web analytical tools exist, which allow tracking of keywords, landing pages, new and return visitor data, and page views. Sophisticated analytics programs can provide detailed mapping of user movement on a site, including where users point and click their mouse (Jantsch, 2012); however, these features increase cost.

Development of the Virtual Center for Teaching Excellence at Creighton University

Creighton University is a private, Catholic, Jesuit university in the Midwest. Creighton is unique in that it provides undergraduate programs in the arts and sciences, business, and nursing; graduate programs at both the master’s and doctoral level; and professional programs in dentistry, medicine, pharmacy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and law. In spite of the diversity of learning experiences available, no physical CTL exists on Creighton’s campus, even though teaching is central to the University’s mission. Instead, educational development is distributed across a variety of units.

At the department level, the title “faculty development coordinator” or “director” is generally used. These individuals are either hired or appointed by the Dean. At the University level, a Center for Academic Innovation provides professional development for faculty teaching online and blended courses as well as for using technology for on ground teaching; a Division of Information Technology provides software training to faculty and staff; and an Office of Academic Excellence and Assessment leads campus wide assessment efforts. Both the Center for Academic Innovation and the Office of Academic Excellence and Assessment utilize a faculty fellowship model that provides a stipend to faculty in exchange for developing and conducting educational programming. Coordination of educational development activities occurs through collaboration between faculty and staff in these areas. This structure has been referred to as a “boutique model” of educational development (Brown, 2009).

Development of the virtual center at Creighton University began at a campus wide meeting of faculty developers from individual departments. It was determined that a “virtual” Center for Teaching Excellence (vCTE) could provide a way for the campus community to share resources. It could also provide a “one stop shop” for full time and adjunct faculty looking for development opportunities. A virtual medium was selected in the absence of a budget or centralized department to organize the effort. Using an adapted version of Bryan et al.’s (2010) framework, the plan was collapsed into two phases: Development and Sustainability (see Figure 1).

Phase 1: Development

Preliminary planning for the vCTE began with establishing a development team. The team, which was comprised of a faculty development coordinator from the College of Nursing, a representative from the Division of Information Technology, a representative from one of the campus libraries, and leaders from the Office of Academic Excellence and Assessment and the Center for Academic Innovation, began meeting regularly in order to craft a mission statement, identify available resources on campus, build a “wireframe” of the website for future content, and select the virtual medium for the site.

Working with University web designers, the library representative was able to begin building the website wireframe using the University’s content management system and website development tool. This ensured that the vCTE had a navigation pattern similar to the rest of the University web pages, consistent branding, and ADA compliant features, such as audio descriptions of images and compatibility with text to speech software.

The team also reviewed the web pages of several exemplary CTLs, such as North Carolina Chapel Hill, Vanderbilt, the University of Minnesota, the University of Wisconsin, and Ohio University, as well as the handful of virtual CTLs already in existence. For example, the University of Wisconsin Colleges system has created a virtual center to provide educational development across 13 campuses. Armstrong Atlantic State University’s virtual center provides faculty with teaching resources and opportunities for online collaboration.

After reviewing external sites and internal resources, the team determined that the site should be divided into five separate content areas or “tabs”: Preparing to Teach, which would contain information for new faculty; Teaching and Learning, a repository of information on pedagogical strategies; Teaching at a Distance, a collection of links to the University’s online teaching resources and standards; Teaching with Technology, a portal for academic technology support services; and Using Library Resources, a collection of links to the campus libraries, books, and journals on the scholarship of teaching and learning and links to external pedagogical resources.

In order to gain buy in from stakeholders and create interest in the site, it was determined that content posted on the vCTE should be written by faculty experts from as many academic areas as possible. Faculty developers from each academic area were asked to attend a meeting to identify potential content ideas and faculty authors. In order to generate as many creative ideas as possible in a short time frame, this meeting was conducted using a modified version of the PechaKucha format. PechaKucha is a fast paced meeting format in which presentations are limited to roughly six and a half minutes, or 20 slides at 20 seconds each (Klein & Dytham, 2014). This meeting was well attended and resulted in several suggestions for content and potential authors as well as volunteers to write weekly teaching tips and a blog for the site. Following the meeting, letters were sent via email to potential authors explaining the purpose of the vCTE and asking them to write a short piece on their area of expertise. Authors were provided with a submission deadline and a template. The template included guidelines for text size and font as well as suggestions to provide submitter contact information, references, and links to external resources.

The process of contacting authors, collecting, formatting, and posting the materials lasted approximately eight months and was performed on a voluntary basis by the development team. The final materials represented on the vCTE were submitted by 13 authors from 10 different departments. In addition to the content pages identified above, a calendar for upcoming development events on campus, a weekly “Teaching Tip,” and a monthly blog about teaching online were also added to the vCTE homepage. Figures 2,3 and 4 depict the vCTE home page, the Teaching and Learning page, and the Teaching at a Distance page.

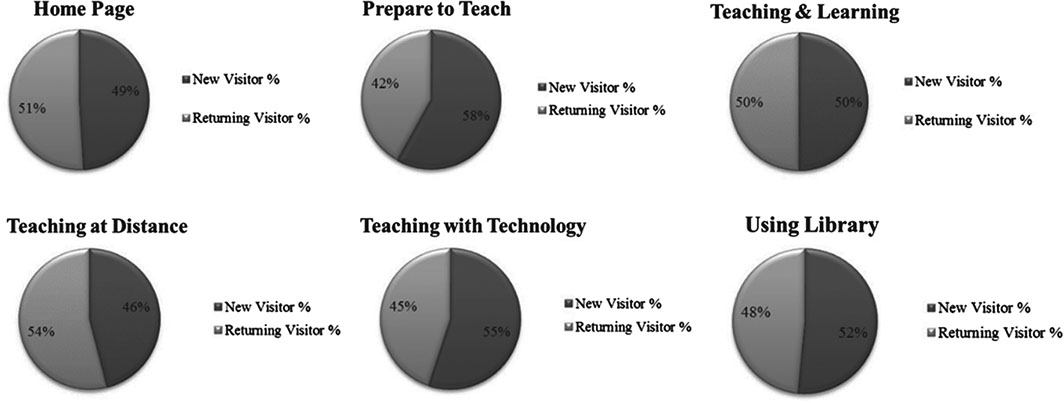

Figure 5. Approximate Average of Monthly New and Return Visitors for Each Page on the Site**Due to changes in the analytical system, number is approximate due to missing data for some pages.

Figure 5. Approximate Average of Monthly New and Return Visitors for Each Page on the Site**Due to changes in the analytical system, number is approximate due to missing data for some pages.After the site was finished, a “go live” date was selected to coincide with New Faculty Orientation on campus. This date was selected so the site could be unveiled to incoming faculty. Prior to going live, feedback on the site was collected from stakeholders using an online survey. The survey was circulated to campus faculty developers, a faculty member, and a staff member in order to gain feedback on the site’s content, ease of navigation, and potential use. The 40 question survey required respondents to review each page of the vCTE for content comprehensiveness, content usefulness, and content organization using a 4 point Likert Scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree). Questions regarding content usefulness were subdivided into usefulness for new faculty and usefulness for experienced faculty. For the homepage, additional items were added to assess clarity of the mission statement, ease of reading, and ease of accessing the blog. In addition, respondents were asked if there was anything that might improve each page.

Participants were also asked a series of technical questions requiring a yes/no response. These questions related to ease of navigation, downloading speed of documents, function of external links, and whether the site was uncluttered, functional, and easy to read. Survey participants were given approximately two weeks to respond and were entered into a prize drawing.

Although the survey was circulated to 11 individuals, only three respondents completed the survey. This may have been because it was distributed in late summer, coinciding with vacation time and planning for the fall semester. The two week return window may also have contributed to the low response rate. Although most items were rated highly, open ended comments expressed concern over not having the vCTE housed in a particular campus department with designated personnel to sustain it. Respondents also requested additional content regarding classroom teaching, feeling that the site focused too much on technology. In spite of the low return rate, feedback from the survey was reviewed by the development team, and changes were made prior to launching the site. For example, the team reviewed the Teaching and Learning page to ensure that pages addressed the needs of faculty teaching both in the classroom and online.

In addition to demonstrating the site at New Faculty Orientation, strategies for marketing the site included distributing brochures to each department, publishing announcements in the University’s electronic newsletters, and emailing links about the site to each faculty developer for distribution to their areas. The majority of marketing efforts were conducted online as there was no dedicated budget for marketing. Brochure printing costs were voluntarily covered by the Center for Academic Innovation and kept to a minimum.

Phase 2: Sustainability

At the time of this writing, the vCTE has been “live” for 14 months, and the project has moved into Phase 2. This phase will focus on increasing the use of the site and developing new content for the site. Central to these activities is the formation of an advisory board, a feature commonly utilized by many physical CTLs (Hanover Research, 2012). The chief function of the advisory board is to establish a yearly content review process and schedule. Current members of the advisory board include faculty developers from individual campus departments and members of the original vCTE development team. In addition to meeting yearly to review the site, members of the advisory board also serve as peer reviewers for content submitted to the vCTE. Instituting a peer review process ensures the accuracy and quality of content posted on the site and also incentivizes faculty to contribute to the vCTE as an opportunity for peer reviewed scholarship.

In order to plan for the future, user data is being tracked through a free version of Google analytics. Fourteen months after “go live,” the vCTE is averaging 182 visits per month to the homepage. Table 1 summarizes the average monthly visits to each page, the average number of pages viewed per visit, and the average page duration in minutes. Monthly analytical trends reveal that usage by both new and return visitors generally increases at the beginning of each semester. For example, in August 2013, when the site was first launched, 78% of visitors were new, and 20% were returning. In January 2014, 84% of visitors were new, and 15% were returning. Initially, this may have reflected the fact that faculty were using the vCTE as a new resource to plan courses and select instructional strategies at the beginning of the semester. However, as knowledge of the vCTE became more widespread, the number of return visits increased. For example, by April of 2014, 22% were new visitors, and 78% were returning. In August 2014, 19% were new visitors, and 81% were returning. This shift in the number of returning visitors may reflect repeated faculty use of the site as they prepare for courses. Figure 5 displays the average new and returning visits to each vCTE page over the first 14 months of operation.

| Page Name | Visits | Pages/Visit | Page Duration (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Page | 182 | 6 | 5.8 |

| Prep to Teach | 38.4 | 9.3 | 12.7 |

| Teach & Learn | 44 | 10.7 | 58 |

| Teach at a Distance | 16 | 17 | 20 |

| Teach w/Technology | 20 | 14.2 | 13.8 |

| Using Libraries | 23 | 16.7 | 34 |

In response to the analytical data, current marketing strategies include updates in the Provost’s e newsletter as well as a monthly, University wide email to alert faculty of new blog postings and updates to the site. This email contains a link to the site, encouraging readers to visit the vCTE on a regular basis. A call for vCTE submissions has also been circulated to faculty through the use of campus listserves and daily online campus announcements. The increased number of return visits may indicate that our strategies have worked in some areas.

Challenges and Future Recommendations

Although the vCTE has demonstrated its utility, several challenges remain in sustaining the site. Table 2 outlines these challenges and recommendations for those considering building a similar virtual center.

| Challenges | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Lack of budget, centralization | Pooling resources between departments Email marketing vs. print brochures Creation of faculty fellowship stipend to lead advisory board Website maintenance donated from student work studies or interns Consider grant applications, such as those available from the Professional Organizational and Development (POD) Network Showcase Virtual Center at new faculty orientation |

| Lack of authors | Creation of peer review system, allowing for scholarship opportunities for faculty |

| Analytical data | Investigate multiple analytical options; level of sophistication should meet objectives being measured |

| Lack of RSS feed for subscription | Monthly email to faculty regarding new content/teaching tips/blogs Utilize Facebook and/or Twitter feed to alert campus of new tips and blog posts Link to WordPress version of blog to allow reader comments |

| Need for faculty feedback | Creation of survey before go live Survey response time should be at least one month; distribute survey when the majority of respondents are on campus Ongoing focus groups to determine development needs |

The most obvious challenge during the sustainability phase is maintaining a cadre of volunteers willing to expend the time necessary to maintain the site. The collaborative nature that spawned the development of the vCTE continues through the formation of the advisory board; however, in the absence of a budget or dedicated home department, eventually, a decision regarding leadership of the advisory board was necessary. As a result, a one year fellowship was created by the Center for Academic Innovation to provide one of the development team members with a modest stipend in exchange for coordinating the vCTE site and advisory board. Members of the advisory board continue to volunteer their time for peer review and website maintenance; however, to date, our site has only received one potential submission for publication in spite of multiple calls.

An additional challenge is determining how to best use the analytics data for future planning. For example, initial analytical data indicates that visitors to the Teaching and Learning Page spend a relatively low amount of time on each page. In comparison, Teaching at a Distance visitors view pages for longer periods of time and view more pages per visit. As we worked more with our analytics tool, we learned that when visitors go to an outside page or view a PDF, this is not counted as time on the page. This analytical data may be an important indicator of educational development needs that should be further investigated, perhaps through the use of faculty focus groups and survey tools on each page.

A final challenge is working within the constraints of the University’s web development tools. Limitations with current software have prevented us from implementing interactive features, such as Rich Site Summary (RSS) feeds for the blogs, teaching tips, and calendar. These strategies could “push” the site to users by generating a notification email when a new teaching tip, calendar, or blog entry is posted. In the absence of this technology, we are piloting the use of a vCTE Facebook site. Users can “follow” posts that alert them to new Teaching Tips, blog posts, and development events. They can also message the vCTE staff with questions related to teaching and learning. Due to constraints with the University’s software, we are working to establish a link to a WordPress blog for readers to communicate with our blog’s author. It is our hope that this feature will create interaction among users as they will also be able to post comments to one another. We will continue to examine the use of additional social networking applications, such as Twitter, in the future.

Our web analytical interpretation is complicated by Google’s use of cookies to track new and return users. Because this method tracks devices rather than users, it is possible that some users may be returning to the site on a different device and are thus counted as new visits. In addition, the University’s web site was updated to better attract prospective undergraduate students; this update changed the direct path to the site for internal users. These changes may have an impact on future visits to the vCTE.

Summary

In summary, Creighton University has created a viable, virtual center for teaching excellence. Through collaborative efforts and shared resources, faculty now have online access to a wealth of educational development resources and campus experts. Future growth and sustainability will be dependent upon data driven planning, continued collaboration, and strong connections. While challenges remain, the lessons learned through Creighton University’s experience provide a framework for institutions considering a similar endeavor.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their assistance and support in the development of the Creighton University Virtual Center for Teaching Excellence as well as the development of this manuscript: Dr. Tracy Chapman, Dr. Mary Ann Danielson, Mary Emmer, Mary Nash, Kathy Craig and Lori Gigliotti.

References

- Austin, A. E., & Sorcinelli, M. D. (2013). The future of faculty development: Where are we going? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2013(133), 85–97. doi:10.1002/tl.20048.

- Brown, B. E. (2009). Moving from a boutique to a concierge model of faculty development: Integrating faculty development to meet individual needs. Adapted from address given at American Association of Colleges and Universities: Shaping Faculty Roles in a Time of Change. April, 2009, San Diego. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCAQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwasc workshop.wikispaces.com%2Ffile%2Fview%2Fboutique conciergeBrown.doc

- Bryan, H. J., Cressman, J., & Diemer, T. (2010 March 16). Collaboration in building a virtual teaching center. Paper presented at the EDUCAUSE Midwest Regional Conference, Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/content.asp?page_id=1022708&Product_Code=MWRC10/SESS19&bhcp=

- Burns, M. (2013). The future of professional learning. Learning and Leading with Technology, June/July, 14–18. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1015164.pdf

- Cercone, K. (2008). Characteristics of adult learners with implications for online learning design. AACE Journal, 16(2), 137–59.

- Frantz, A. C., Beebe, S. A., Horvath, V. S., Canales, J., & Swee, D. (2005). The roles of teaching and learning centers. To Improve the Academy, 23, 72–90.

- Hanover Research (2014). Best practices in faculty development. Washington, DC: Hanover Research.

- Hanover Research (2012). Overview of integrated faculty development centers. Washington, DC: Hanover Research.

- Jantsch, J. (2012). The 10 smartest web analytics tools. Technology, (July 23) Retrieved from https://www.americanexpress.com/us/small-business/openforum/articles/the-10-smartest-web-analytics-tools/.

- Klein, A., & Dytham, M. (2014). PechaKucha 20 images x 20 seconds. Retrieved from http://www.pechakucha.org/faq

- MacDonald, K. (2009). Eight ways to support faculty needs with a virtual teaching and learning center. Faculty Focus, (August 25) Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/faculty development/eight ways to support faculty needs with a virtual teaching learning center/.

- Neal, E., & Peed Neal, I. (2010). Promoting your program and grounding it in the institution. In K. J. Gillespie & D. L. Robertson (Eds.), A guide to faculty development (pp. 99–115). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Schroeder, C. (2011). Coming in from the margins: Faculty development’s emerging organizational development role in institutional change. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Shea, T. P., Sherer, P. D., & Kristensen, E. W. (2002). Harnessing the potential of online faculty development: Challenges and opportunities. To Improve the Academy, 20, 162–79.

- Sherer, P. D., Shea, T. P., & Kristensen, E. W.(2003 March). Online communities of practice: A catalyst for faculty development. Innovative Higher Education, 27(3), 183–194. doi:10.1023/A:1022355226924

- Sorcinelli, M. D. (2002). Ten principles of good practice in creating and sustaining teaching and learning centers. In K. H. Gillespie, L. R. Hilsen & E. C. Wadsworth (Eds.), A guide to faculty development: Practical advice, examples, and resources. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Schumann, D. W., Peters, J., & Olsen, T. (2013). Cocreating value in teaching and learning centers. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 133, 21–32.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). HHS Section 508 Accessibility Checklists. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/web/508/accessiblefiles/checklists.html

- Van Note Chism, N. (1998). The role of educational developer in institutional change: From the basement office to the front office. To Improve the Academy, 17, 141–54.

- Weiss, J., & Enyeart, C. (2009). Designing a faculty development center: Custom research brief. Washington, DC: Education Advisory Board.