Tracking POD's Engagement with Diversity: A Content Analysis of To Improve the Academy and POD Network Conference Programs From 1977 to 2011

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This study examines the degree to which sessions from the annual Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network Conference and articles from To Improve the Academy engage questions of diversity. The titles and abstracts of 3,946 conference sessions and 560 journal articles were coded for presence and type of diversity. A significant variation in inclusion of diversity over time was found for the conference sessions (p < .001) but not the journal articles. Overall, the findings suggest that the organization has been inconsistent in its scholarly engagement with diversity and should work to encourage more regular engagement with diversity by its members.

Keywords: Diversity, POD Network, Multicultural Organization, To Improve the Academy

This project emerges from a simple question: Has the Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network been engaging less with diversity in recent years? It was a question raised repeatedly during my six year tenure (2006–2012) on the executive board of POD's Diversity Committee, often by long time POD members who were concerned that the organization was becoming less intentional in its commitments to diversity. Leafing through the annual conference program and scanning the titles in To Improve the Academy, these individuals saw fewer presentations and articles explicitly addressing diversity than they expected. However, without the data to verify those perceptions, it was sometimes difficult to make the case that a problem actually existed.

Although a simple question, it is one that points to a larger, and much more complex, project: the intent to shape POD into what Jackson and Holvino (1988 term a multicultural organization, one that practices genuine inclusion of all its members and acts to “eradicate social oppression in all forms” (Ouellett & Stanley, 2004). Stanley & Ouellett (2000) argue that POD is uniquely positioned as a potential training ground for educational developers interested in becoming diversity change agents on their own campuses. They assert that through the work of identifying and building those “organizational ‘muscles’” necessary for POD to become a truly multicultural organization, POD members also strengthen the skills they need to foster organizational growth around diversity in their home institutions (p. 39). The representation of diversity in POD's conferences and publications thus becomes an important marker of how well the organization is attending to this larger project of not merely attracting a diverse membership but also supporting its members in challenging structural inequalities within higher education.

In this study, I seek to determine (a) the extent to which POD has attended to questions of diversity in its conference sessions and journal articles, (b) whether there has been any variation in the percentage of diverse content over time, and (c) the degree to which particular identity groups are discussed in POD scholarship. In doing so, I hope to “operationalize” this aspect of POD's diversity mission and to set a baseline for future assessments of whether POD's conferences and journals sufficiently reflect and support the organization's commitment to diversity (Jacobson, Borgford Parnell, Frank, Peck, & Reddick, 2001).

Defining Diversity

Before proceeding, it is important to note that diversity is a slippery term. Taken literally, it is a reference to multiplicity—to the presence of variety within a sample or group. However, in recent decades in the United States, diversity has also come to stand in as a less threatening shorthand for historically underrepresented populations, with the connotation typically suggesting minoritized racial and ethnic groups. So when POD members speak of a desire to “increase diversity” within their membership or to a “lack of diversity” in a conference program, they are most likely referring to an absence of perspectives from people of color—though they may also be referring to women, LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning) individuals, people with disabilities, etc.—and to a broader social justice imperative to address the structural inequalities faced by such groups. For the sake of simplicity, in this study I follow the precedent of using the terms diversity and cultural diversity interchangeably when referring generally to historically underrepresented groups or to those systems of social inequality that privilege some groups and disadvantage others (Kamphoff, Gill, Araki, & Hammond, 2010; Morrow, Burris Kitchen, & Der Karabetian, 2000; Price et al., 2005).

POD's History of Valuing Diversity

Histories of the educational development movement often tie its origins to the social and political movements of the late 1950s and 1960s (Gillespie, 2000; Rice, 2007; Sorcinelli, Austin, Eddy & Beach, 2006). Ouellett (2010) writes that as students began to demand greater agency over their own educations, faculty began to question whether a reward system based solely on research productivity sufficiently reflected the importance of their contributions in the classroom. It is not surprising, then, that POD—emerging as it did out of this call for more holistic understandings of faculty work and greater respect for the humanity of our students—founded itself as an organization dedicated to valuing individuals and individual growth. That dedication is echoed today in the near constant refrain that POD seeks to be the most “welcoming” professional organization in higher education as well as in the organization's long history of prioritizing diversity as a value, even if those efforts have been met with varying degrees of success.

In their “taking stock” of the history of diversity related initiatives within POD, Stanley and Ouellett (2000) write that although POD had made efforts towards valuing diversity ever since its founding in 1975, those efforts had been “uneven … in terms of conference keynotes and themes; programming streams; our literature; the social, cultural, and racial identity makeup of our members; the types of institutions represented in our membership; the leadership makeup of the Core; and the level of commitment among our members” (p. 43). They point to POD's 1991 Mission Statement as a turning point in the institutionalization of that commitment. Stating as a core conviction that “people have value, as individuals and as members of groups” (Gillespie, 2000, p. 29), the 1991 statement also asserts that “POD should strive at all points to be responsive to human needs. … [A]s our members change and as higher education changes, so POD must change” (Stanley & Ouellett, 2000, p. 40).

Not long after, in 1993, a proposal was put forward under the leadership of then president Donald Wulff to establish a Diversity Committee (DC) within POD. Formalized in 1994 (and later termed the Diversity Commission), the DC has since worked to make diversity a priority within POD and to recruit a more diverse membership for the organization (Ouellett & Stanley, 2004). The first POD committee to be given a budget, the DC developed travel grant and internship grant programs to encourage participation from underrepresented groups at the conference and in educational development more broadly, with a particular emphasis on recruiting those from historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The DC went on to expand its mission in 2011 to include not only the recruitment and retention of a diverse membership to POD and to the field of educational development but also to “cultivate greater critical attention to questions of diversity in our work” (“Standing committees,” n.d.).

POD's most recent strategic plan (for 2013–2018)—which includes updated vision and mission statements, as well as a new articulation of the organization's core values—is much more explicit in defining POD's commitment to valuing diversity (“POD Network,” 2012). For example, among the eight core values listed, three speak directly to principles of diversity (“inclusion,” “diverse perspectives,” and “advocacy and social justice”) and two others address diversity indirectly (“collegiality” and “respect/ethnical practices”) (p. 1). The strategic goals for 2013–2018 include a commitment to “acting on [POD's] commitment to inclusion and diversity” (p.1), with specific targets spelled out for continued support of travel and internship grants, ongoing surveying of the POD membership regarding their experiences of diversity and inclusion, greater attention to conference accessibility, and outreach to underrepresented constituents and organizations (p. 3).

With this steady trajectory throughout POD's history of an increasingly visible commitment to diversity among its leadership, the question of how that commitment has been reflected in the scholarly work of its members becomes even more interesting.

Method and Analysis

In order to explore this question, I chose to conduct a content analysis of the titles and abstracts (when available) from all past editions of To Improve the Academy as well as from the available programs of all past POD Network conferences to determine the presence of references to cultural diversity. Journal data was accessed using the POD Network website (”To Improve,” n.d.) which hosts a page listing all journal articles and titles from the first issue published in 1982 through 2011 (excluding 2003 when no volume was published). Conference programs were provided by the POD Network executive director and included all past conferences from 1977 through 2011 (excluding 1978, 1981, and 2001, which were either unavailable or incomplete).

Categories of Analysis

Coding sought to identify for both journal articles and conference sessions: (a) whether the title or abstract (if available) contained references to cultural diversity, (b) the specific category of diversity referenced, and (c) all key words or phrases in the title and abstract related to diversity. Conference sessions were also coded for the type of session (e.g., regular, poster, discussion, plenary, or keynote) and length (in minutes). For this article, only those coded as plenary or keynote are specifically discussed.

Coding categories were defined prior to the analysis (although some definitions were refined during the coding process to reflect nuances in the data). Those categories were age, class, disability, gender, gender identity, indigenous, international, nationality, race/ethnicity, religion, sex, and sexuality. A “general” category was also included for references addressing diversity more broadly (e.g., multiculturalism).

In distinguishing between gender, gender identity, and sex, I defined gender as those socially constructed roles traditionally defined as “masculine” and “feminine” within a particular culture, gender identity as the alignment between gender and biological sex (e.g., cisgender or transgender), and sex as one's biological status. The categories international and nationality were established to distinguish between those references that implied the crossing of national boundaries (e.g., international graduate students teaching in the United States) from those about distinct national or regional identities (e.g., Korean, Middle Eastern). The full list of diversity categories and their definitions can be found in Table 1.

| Category of Analysis | Definition |

|---|---|

| Age | References age groups that have traditionally been underrepresented as well as stigmatized within U.S. higher education or to inequalities tied to age (e.g., nontraditionally aged students, ageism) |

| Class | References socioeconomic status and/or identity for those groups traditionally underrepresented in U.S. higher education as well as inequalities tied to class (e.g., working class, poor, first generation) |

| Disability | References those with physical, emotional, cognitive, and/or social disabilities as well as inequalities tied to ability (e.g., learning disability, autism, deaf, visually impaired, wheelchair user, anxiety, ableism, ADA) |

| Gender | References women as well as inequalities tied to gender (e.g., woman, female, gender bias, sexist, feminist) |

| Gender identity | References those whose gender does not align in traditional ways with their biological sex as well as inequalities tied to gender identity (e.g., transgender, transsexual, LGBTQ [only if there's explicit reference to the “T” of the acronym]) |

| General | References the existence of cultural diversity more generally as well as inequalities tied to identity (e.g., multicultural, culture, diversity, difference, intersectionality, stereotyping, stereotype threat, chilly climate, inclusive classrooms, difficult dialogues) |

| Indigenous | References groups that identify as indigenous to their regions as well as inequalities tied to indigenous status (e.g., Native American, Maori) |

| International | References that reflect interactions across nations when at least one country lies outside the U.S. context as well as inequalities tied to international status (e.g., international, transnational, global, study abroad, English language learners) |

| Nationality | References discrete national, regional, or “continent” identities outside the U.S. context as well as inequalities tied to nationality (e.g., British, East Asian, African, Kenyan, Middle Eastern) |

| Race/Ethnicity | References U.S. racial or ethnic groups that have traditionally been underrepresented or stigmatized within U.S. higher education as well as inequalities tied to race or ethnicity (e.g., African American, Black, Latina, Asian American, racism, White privilege) |

| Religion | References religious traditions historically underrepresented or stigmatized within the U.S.—and interactions across religious traditions—as well as inequalities tied to religious identity (e.g., Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, atheist, interfaith dialogue) |

| Sex | References those whose biological sex seems to fall outside the typical binary definition of male or female as well as inequalities tied to biological sex (e.g., intersex, disorders of sexual development) |

| Sexuality | References groups whose self defined direction of sexual interest has traditionally been underrepresented or stigmatized within U.S. higher education as well as inequalities tied to sexuality (e.g., gay, queer, bisexual, asexual, pansexual, lesbian, LGBQ, heteronormative) |

Reliability and Analysis

Initial coding was conducted by a trained research assistant after she and I achieved 95% reliability in our initial coding of approximately 100 journal articles. We also consulted when questions arose throughout the coding process and so further refined our common understanding of operational definitions. Furthermore, the coding protocol included transcription of key words and phrases, which allowed me to conduct a final review of the entire set of records coded as focusing on diversity to double check their categorization. During this final review, I made changes in fewer than 1% of all records.

Once coding was complete, a series of chi square analyses were used to assess differences in cultural diversity references over time. Because of the relatively small sample size in each year's data set—and the great variation evident year to year—I chose to group the data into five year intervals. The journal articles were divided into six time periods (1982–1986, 1987–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001, 2002–2006, and 2007–2011) and conference articles were divided into seven periods (1977–1981, 1982–1986, 1987–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001, 2002–2006, and 2007–2011). The level of significance was set at p = .05 for all analyses.

Results

Overall Diversity Content in Journal Articles

Of the 560 journal articles coded, 12.7% (n = 71) mentioned cultural diversity in some way in the title or abstract. A chi square analysis revealed no difference over time in inclusion of cultural diversity, X2 (5, N = 560) = 3.35, p = .65. Although not statistically significant, there has been some increase over time in the percentage of articles addressing diversity, moving from 7.5% in the 1982–1986 period to 16.7% in 2002–2006 (see Figure 1). The most recent period analyzed (2007–2011) dips back to 12.4%; although the final two years of that period, 2010 and 2011, swing back up to 19.0% and 18.2% respectively (see Table 2).

Figure 1. Percentage of Journal Articles per Five Year Interval That Reference Diversity in the Title or Abstract (1982–2011)

Figure 1. Percentage of Journal Articles per Five Year Interval That Reference Diversity in the Title or Abstract (1982–2011)| Year | Diversity Referenced | Total Articles | Percentage of Annual Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 2 | 21 | 9.5% |

| 1983 | 1 | 17 | 5.9% |

| 1984 | 0 | 18 | 0.0% |

| 1985 | 3 | 19 | 15.8% |

| 1986 | 1 | 18 | 5.6% |

| 1987 | 2 | 15 | 13.3% |

| 1988 | 0 | 19 | 0.0% |

| 1989 | 2 | 16 | 12.5% |

| 1990 | 3 | 19 | 15.8% |

| 1991 | 4 | 22 | 18.2% |

| 1992 | 4 | 27 | 14.8% |

| 1993 | 3 | 18 | 16.7% |

| 1994 | 4 | 24 | 16.7% |

| 1995 | 1 | 15 | 6.7% |

| 1996 | 1 | 17 | 5.9% |

| 1997 | 4 | 19 | 21.1% |

| 1998 | 4 | 18 | 22.2% |

| 1999 | 3 | 17 | 17.6% |

| 2000 | 1 | 20 | 5.0% |

| 2001 | 2 | 18 | 11.1% |

| 2002 | 3 | 18 | 16.7% |

| 2004 | 4 | 20 | 20.0% |

| 2005 | 2 | 20 | 10.0% |

| 2006 | 4 | 20 | 20.0% |

| 2007 | 2 | 21 | 9.5% |

| 2008 | 3 | 20 | 15.0% |

| 2009 | 0 | 21 | 0.0% |

| 2010 | 4 | 21 | 19.0% |

| 2011 | 4 | 22 | 18.2% |

The annual data shows the period from 1989 to 1994 as engaging the most consistently with questions of diversity, with those six consecutive volumes including greater than 12% diverse content each (and ranging from 12.5% to 18.2%). The 2001–2006 period also shows more consistent engagement, with five years of volumes with at least 10% diverse content (ranging from 10.0% to 20.0%). The years 1997 and 1998 mark the highest percentage of diversity related articles in the journal's history, with 21.1% and 22.2%, respectively. See Table 2.

Diversity Focus of Journal Articles

When coding articles for diversity focus, we marked all categories that applied to a single article (to accommodate those that engaged with more than one kind of diversity). Of those articles focusing on cultural diversity, five areas were addressed most frequently: general diversity, gender, race/ethnicity, nationality, and international concerns. Socioeconomic class, disability, and sexuality were addressed in fewer than 1% of articles coded. And age, indigenous status, religion, and gender identity were not addressed at all. See Table 3.

| Category | Diversity Referenced | Percentage of Total (N = 560) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0 | 0.0% |

| Class | 1 | 0.2% |

| Disability | 3 | 0.5% |

| Gender | 17 | 3.0% |

| Gender Identity | 0 | 0.0% |

| General | 29 | 5.2% |

| International | 8 | 1.4% |

| Indigenous | 0 | 0.0% |

| Nationality | 9 | 1.6% |

| Race/Ethnicity | 10 | 1.8% |

| Religion | 0 | 0.0% |

| Sexuality | 1 | 0.2% |

Chi square analyses of the five most frequent categories showed no significant variation in their inclusion over time; however, general diversity was close to significance with X2 (5, N = 560) = 10.42, p = .06. Despite this lack of significance, I find it worth noting the slight shifts in these areas of focus over time (see Figure 2). For example, general diversity was addressed most frequently in the 1992–1996 time period (8.9%), with 2002–2006 following close behind (7.7%). Gender was discussed most heavily in the 1980s (4.3% in 1982–1986 and 5.5% in 1987–1991) but then not at all in 2002–2006. The greater focus on nationality in 1992–1996 (2.0%) and 1997–2001 (4.3%) falls to 0% in 2002–2006 and 2007–2011. It is in that time frame, though, when international issues become more prevalent (3.8% in 2002–2006 and 1.9% in 2007–2011). Race is given the most attention in 1997–2001 (3.3%) and 2002–2006 (2.6%).

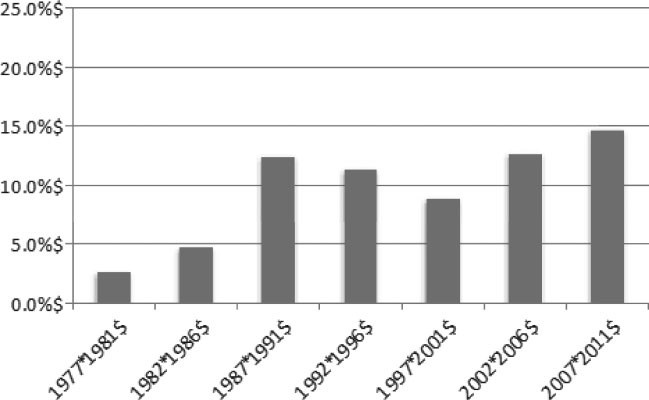

Overall Diversity Content in Conference Sessions

Of the 3,946 conference sessions coded, 11.5% (n = 453) mentioned some aspect of cultural diversity in the title or abstract. A chi square analysis revealed a significant difference over time in inclusion of diversity, X2 (6, N = 3,946) = 39.12, p < .001. This significance does not reflect a steady upward trend over the 35 years represented (see Figure 3). Rather, there seem to be two peaks: from the late 1980s to the mid 1990s (with 12.4% in 1987–1991 and 11.3% in 1992–1996) and then again in the 2000s (with 12.7% in 2002–2006 and 14.7% in 2007–2011). It is worth noting, however, that the high percentage for 2007–2011 is largely due to the 2011 conference, which was held jointly with the Historically Black Colleges & Universities Faculty Development Network and featured diversity in 23.4% of sessions (see Table 4). Removing 2011 as an outlier reveals only 12.1% of the 2007–2010 conference sessions with a diverse focus, a slight dip from the 12.7% in the previous five years.

Figure 3. Percentage of Conference Sessions per Five Year Interval That Reference Diversity in the Title or Abstract (1977–2011)

Figure 3. Percentage of Conference Sessions per Five Year Interval That Reference Diversity in the Title or Abstract (1977–2011)| Year | Diversity Referenced | Total Sessions | Percentage of Annual Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | 1 | 47 | 2.1% |

| 1979 | 2 | 50 | 4.0% |

| 1980 | 1 | 58 | 1.7% |

| 1982 | 0 | 45 | 0.0% |

| 1983 | 2 | 59 | 3.4% |

| 1984 | 4 | 53 | 7.5% |

| 1985 | 8 | 92 | 8.7% |

| 1986 | 1 | 71 | 1.4% |

| 1987 | 2 | 70 | 2.9% |

| 1988 | 7 | 84 | 8.3% |

| 1989 | 17 | 82 | 20.7% |

| 1990 | 9 | 70 | 12.9% |

| 1991 | 10 | 57 | 17.5% |

| 1992 | 16 | 87 | 18.4% |

| 1994 | 14 | 107 | 13.1% |

| 1995 | 5 | 96 | 5.2% |

| 1996 | 12 | 126 | 9.5% |

| 1997 | 12 | 139 | 8.6% |

| 1998 | 12 | 117 | 10.3% |

| 1999 | 10 | 165 | 6.1% |

| 2000 | 18 | 169 | 10.7% |

| 2002 | 25 | 161 | 15.5% |

| 2003 | 10 | 118 | 8.5% |

| 2004 | 19 | 199 | 9.5% |

| 2005 | 26 | 226 | 11.5% |

| 2006 | 36 | 212 | 17.0% |

| 2007 | 29 | 249 | 11.6% |

| 2008 | 37 | 271 | 13.7% |

| 2009 | 23 | 198 | 11.6% |

| 2010 | 21 | 194 | 10.8% |

| 2011 | 64 | 274 | 23.4% |

Similar to the journal findings, the annual data for the conferences also shows the period from 1989 to 1994 as engaging consistently with questions of diversity, each year including greater than 12% diversity focused sessions (ranging from 12.9% to 20.7%). The 2005–2011 period shows the longest engagement: seven consecutive conferences with at least 10% diverse content (ranging from 10.8% to 23.4%). See Table 4.

Diversity Focus of Conference Sessions

The most common areas of focus for conference sessions are the same as those for journal articles: general diversity, race/ethnicity, gender, international concerns, and nationality. Socioeconomic class, disability, sexuality, age, indigenous status, religion, and gender identity were addressed in fewer than 1% of articles coded. No category went completely unaddressed in the conference sessions. Gender identity was discussed the least frequently (in only 0.1% of sessions). See Table 5.

| Category | Diversity Referenced | Percentage of Total (N = 3,946) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 11 | 0.3% |

| Class | 15 | 0.4% |

| Disability | 31 | 0.8% |

| Gender | 86 | 2.2% |

| Gender Identity | 3 | 0.1% |

| General | 211 | 5.3% |

| International | 80 | 2.0% |

| Indigenous | 10 | 0.3% |

| Nationality | 59 | 1.5% |

| Race/Ethnicity | 113 | 2.9% |

| Religion | 7 | 0.2% |

| Sexuality | 19 | 0.5% |

| Five Year Interval | Diversity Referenced | Total Plenary Sessions | Percentage of Five Year Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977–1981 | 0 | 6 | 0.0% |

| 1982–1986 | 1 | 12 | 8.3% |

| 1987–1991 | 1 | 17 | 5.9% |

| 1992–1996 | 1 | 9 | 11.1% |

| 1997–2001 | 4 | 17 | 23.5% |

| 2002–2006 | 2 | 13 | 15.4% |

| 2007–2011 | 3 | 13 | 23.1% |

Chi square analyses of the five most frequent categories showed significant variation for each in their inclusion over time. For general diversity issues, X2 (6, N = 3946) = 23.27, p < .001, the 1992–1996 time period showed the highest percentage of diversity related sessions (7.7%) with a second peak in 2002–2006 (7.0%). Race was discussed most frequently in 2007–2011 (4.6%), X2 (6, N = 3946) = 28.85, p < .001, and had previously seen a peak in 1987–1991 (3.9%). Gender was discussed with the most frequency in 1987–1991 (6.1%), X2 (6, N = 3946) = 30.35, p < .001, but didn't raise above 2.2% in any other time period. International concerns slowly increased their visibility from the early 1990s (moving from 0.5% in 1992–1996 to 3.7% in 2007–2011), X2 (6, N = 3946) = 37.97, p < .001. And nationality has also seen a more recent increase (from 1.2% in 1997–2001 to 2.8% in 2007–2011), X2 (6, N = 3946) = 26.26, p < .001. See Figure 4.

Diversity Content of Featured Sessions

Since plenary sessions and keynotes are chosen to reflect the organization's sense of those issues most pressing to its membership, tracking the representation of diversity in these addresses can be particularly informative. Of the 87 sessions coded as either a plenary or keynote, 12 (13.8%) included some reference to diversity in the title or abstract. A chi square analysis of this subset revealed a nonsignificant difference in inclusion of cultural diversity over time, X2 (6, N = 87) = 3.91, p = .69. Despite this lack of statistical significance, it is worth noting that only three plenary or keynote sessions addressed diversity in the first 20 years of the conference, while there were nine in the 15 years leading up to 2011. Race was the most frequently mentioned category of diversity at keynote and plenary sessions (present in the titles or abstracts of six sessions); general diversity was the next most frequent (present in four sessions); and gender and nationality were each present in two sessions.

Discussion

By choosing to focus solely on the published conference programs and journals, this study obviously is unable to account for many other potentially useful measures of the POD Network's engagement with diversity. For example, this study does not look at submissions that were not accepted and so cannot ascertain the reason for a particular year's low numbers. Was it the result of too few submissions or of a low acceptance rate of diversity related studies? In addition, the lack of demographic information in these publications also limits the ability to measure the percentage of conference presenters or article authors who identify as coming from an underrepresented group. Being able to measure how various groups are represented within our conferences and publications would certainly add valuable insight into our understanding of how POD operates as a multicultural organization.

If any conclusion can be drawn from the analysis, it is that POD's engagement with diversity—both in its conferences and its journals—has varied greatly over its history, with percentages ranging from 0.0% to 23.4% for conference sessions and from 0.0% to 20.2% for journal articles. This variation does not follow a strictly upward progression but instead marks periods of more intense focus followed by lulls in interest. The period from 1989 to 1994 is noticeable in the consistent engagement with diverse topics that happened in both the journals and conferences from that time. A future study might unpack the historical and organizational contexts of that period to determine what factors might have contributed to that span of heightened attention to diversity.

Closer to our present moment, the journal data continues to be inconsistent (dipping to 0.0% in 2009 and then leaping back up to 19.0% and 18.2% in 2010 and 2011, respectively) and so doesn't give an indication of whether we can expect a peak or lull in the coming years. Recent conference data is more consistent, showing an engagement with diversity in greater than 10% of sessions from 2005 to 2011. This period still falls short of the level of engagement seen in the 1989 to 1994 stretch (16.4% in 1989–1994; 14.5% in 2005–2011) but a hopeful reading would see this current period of more sustained attention serving as a strong foundation for future growth.

A clear trend over both sets of data is that greater diversity is needed within our engagements with diversity. Questions of class, disability, gender identity, religion, indigenous identity, and sexuality all have been underrepresented in both our conference sessions and our journal articles. This, of course, is not to suggest that we are somehow focusing too much on questions of race, nationality, or gender, but that as we seek to further increase our attention to diversity, we must also be intentional in supporting work that expands our understanding of the needs of these populations that go largely unmentioned in the POD scholarship. Expanding our focus in this way not only broadens our understanding of these particular groups but also encourages greater attention to the intersections among these various identity categories (Banks, Iuzzini, & Pliner, 2011).

Returning to the initiating question of whether discussions of diversity have become less prevalent in POD conferences and publications, this study suggests the answer is both yes and no. Looking historically, the current period certainly shows a greater engagement with diversity than in many periods in POD's history (particularly when we look at the recent conference data). However, considering the rapid pace of demographic change among student and faculty populations—and the continued importance placed on diversity by POD and its members’ home institutions—the modest improvements we've seen seem to fall short. The momentum on these questions that seemed to be building in the early 1990s has fallen off, and it is uncertain whether the organization is poised to regain that momentum. If nothing else, this study suggests that POD has not been successful in consistently engaging with diversity year to year and so needs to take steps to build a more sustained attention to diversity among its members. The recommendations below seek to identify some ways POD might work to develop more consistency in this area.

Recommendations

The recommendations that follow are informed by suggestions in the literature as well as by conversations that have occurred in Diversity Committee meetings and POD Sponsored Sessions over many years:

Implement ongoing assessment of POD's diversity scholarship. Now that a baseline has been set, future tracking of conference session and journal article topics can be more meaningfully interpreted to determine if negative or positive trends are developing. Such tracking data can be shared across POD's various committees to inform those working on POD's publications, electronic resources, conference planning, and graduate student development.

Expand strategic goals beyond recruitment and retention. The high level attention to diversity in POD's 2013–2018 strategic plan is commendable; however, its target goals are in large part limited to strategies only meant to diversify the POD membership. Such a narrow focus on recruitment keeps us firmly in the stage Jackson and Holvino (1988) describe as the “affirmative action organization,” rather than moving us along the continuum to becoming a truly self reflective and committed “multicultural organization.” Defining future targets to also focus on sustaining—and expanding—diverse scholarship among POD members could be one positive step toward that goal.

Establish plenary session guidelines. Plenary and keynote sessions are among the most visible expressions of what POD values. It is not unreasonable to expect that conference organizers aim to have at least 25% of plenary sessions focused explicitly on research related to diversity—and to be conscious of including those areas of diversity less often addressed at POD (class, sexuality, gender identity, etc.). In addition, invitations to all plenary speakers should be explicit in conveying POD's commitment to diversity and should encourage speakers to address the ways that diversity intersects with their presentation topics.

Establish a diversity research award. The Menges Award, established in 2000, is given out at each POD Conference to recognize outstanding original research in educational development. The high visibility of the Menges award—with award winning sessions marked clearly in the conference program and also featured on “awards night” at the conference—sends a clear message that POD values and seeks to encourage rigorous, evidence based research by its members. A similar award developed to recognize outstanding work on diversity could serve to reinforce POD's commitment to diverse scholarship and bring greater visibility to these efforts.

Continue improving conference accessibility. The 2013–2018 strategic plan's focus on improving accessibility at conferences for those with disabilities is an important step, both for encouraging participation by individuals with disabilities and also for raising the visibility of issues of disability within our work. Although this may seem to be an initiative focused solely on building our membership, the related work of educating our members about the roles they play in creating access has the potential to expand their scholarly attention to disability, as well.

Establish an educational development diversity institute. In order to create space for more intentional reflection about educational developers’ roles as diversity change agents, POD could create a diversity institute modeled after the Organizational Development Institutes organized in conjunction with the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U). Partnering with organizations such as the National Conference on Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education (NCORE) or the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) could lead to exciting dialogues about the future of diversity within higher education.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by a grant from the Professional and Organizational Development Network awarded to Stacy Grooters.

My heartfelt thanks goes to Ashley Trebisacci for her tireless work in coding 35 years of conference presentations and journal articles, as well as to Bronwyn Bleakley, Robert Carver, William Ewell, and Hilary Gettman for their invaluable guidance in project design and data analysis.

References

- Banks, C., Iuzzini, J., & Pliner, S. (2011). Intersecting identities and the work of faculty development. In To improve the academy: Vol. 29. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 132–144). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Gillespie, K. H. (2000). The challenge and test of our values: An essay of collective experience. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 18. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 27–37). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Jackson, B. & Holvino, E. (1988). Developing multicultural organizations. Creative Change: The Journal of Religion and Applied Behavioral Sciences, 9(2), 14–19.

- Jacobson, W., Borgford Parnell, J., Frank, K., Peck, M., & Reddick, L. (2001). Operational diversity: Saying what we mean, doing what we say. In D. Lieberman & C. Wehlburg (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 20. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Kamphoff, C. S., Gill, D. L., Araki, K., & Hammond, C. C. (2010). A content analysis of cultural diversity in the association for applied sport psychology's conference programs. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(2), 231–245.

- Morrow, G.P., Burris Kitchen, D., & Der Karabetian, A. (2000). Assessing campus climate of cultural diversity: a focus on focus groups. College Student Journal, 34(4), 589–603.

- Ouellet, M. L. (2010). Overview of faculty development: History and choices. A guide to faculty development (2nd ed.). San Francisco CA: Wiley.

- Ouellett, M. L., & Stanley, C. A. (2004). Fostering diversity in a faculty development organization. In C. M. Wehlburg & S. Chadwick Blossey (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 22. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- POD Network 5 year strategic plan 2013–2018. (2012). Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://podnetwork.org/about us/mission/

- Price, E., Gozu, A., Kern, D., Powe, N., Wand, G., Golden, S., & Cooper, L. (2005). The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(7), 565–571.

- Rice, R. E. (2007). It all started in the sixties: Movements for change across the decades—a personal journey. In D. R. Robertson & L. B. Nilson (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 25. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 3–17). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., Eddy, P. L., & Beach, A. L. (2006). Creating the future of faculty development: Learning from the past, understanding the present. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Standing committees. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://podnetwork.org/about us/pod governance/committees/

- Stanley, C. A. & Ouellett, M. L. (2000). On the path: POD as a multicultural organization. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 18. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 38–54). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- To Improve the Academy index. (n.d.) Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://podnetwork.org/publications/to improve the academy index/