8 Tough-Love Consulting

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

WHILE IT is important for faculty developers to build trust in consultation relationships, many of us find ourselves in challenging situations. With what we call the provocative consultation approach, the faculty developer adopts a more direct role and attempts to address perceived challenges in a frank discussion. This chapter uses three case studies-one focusing on a graduate student, one a pretenured faculty member, and one a multidisciplinary course-to discuss how faculty developers can effect change in difficult consultations through use of a more confrontational style.

Conventional wisdom suggests that it is crucial to establish trust and warmth in a consultation relationship between a faculty developer and instructor, creating an environment that fosters growth and focuses on goals and new ideas without defensiveness or threat. Yet as faculty developers, many of us find ourselves in situations in which we need to challenge or push, perhaps even to the point of discomfort. Some faculty members may struggle with issues of social intelligence, as Rosier observes {2011), while others may be apathetic about confronting known problems, and it can be difficult for faculty developers to address these touchy situations. However, the call endures for faculty developers to persist as advocates for change (Fletcher & Patrick, 1998), stepping beyond traditional roles to become change agents through individual consultation (Zahorski, 1993).

This chapter discusses how faculty developers can observe that call to action as we consider the impact of consultation style for initiating pedagogical transformation and the results of employing a more confrontational style. With what we informally call the "tough love" or "provocative" consultation approach, the faculty developer takes on a more direct role and attempts to bring up perceived challenges in a frank discussion. We examine what happens when consultants adopt a consultation method that may be outside their comfort zones to effect change with graduate students, faculty members, or even departments reluctant to recognize negative attitudes, consistently poor student feedback, or problematic communication patterns and social skills.

Resistance to Faculty Development

Both new and experienced faculty developers know that resistance to faculty development is an ongoing obstacle, and the literature verifies this dynamic (Hodges, 2006; Lucas, 2001; Smith & Smith, 2001; Turner & Boice, 1986). Turner and Boice (1986), for instance, observe that faculty often struggle to assimilate suggestions for change, perhaps appearing inflexible and unappreciative; they suggest that resistant faculty sometimes perceive faculty development as implying incompetence or remediation. Hodges (2006) adds that fear-such as fear of loss of control or content, of embarrassment, or of failure-is also a major factor in faculty resistance to development and change.

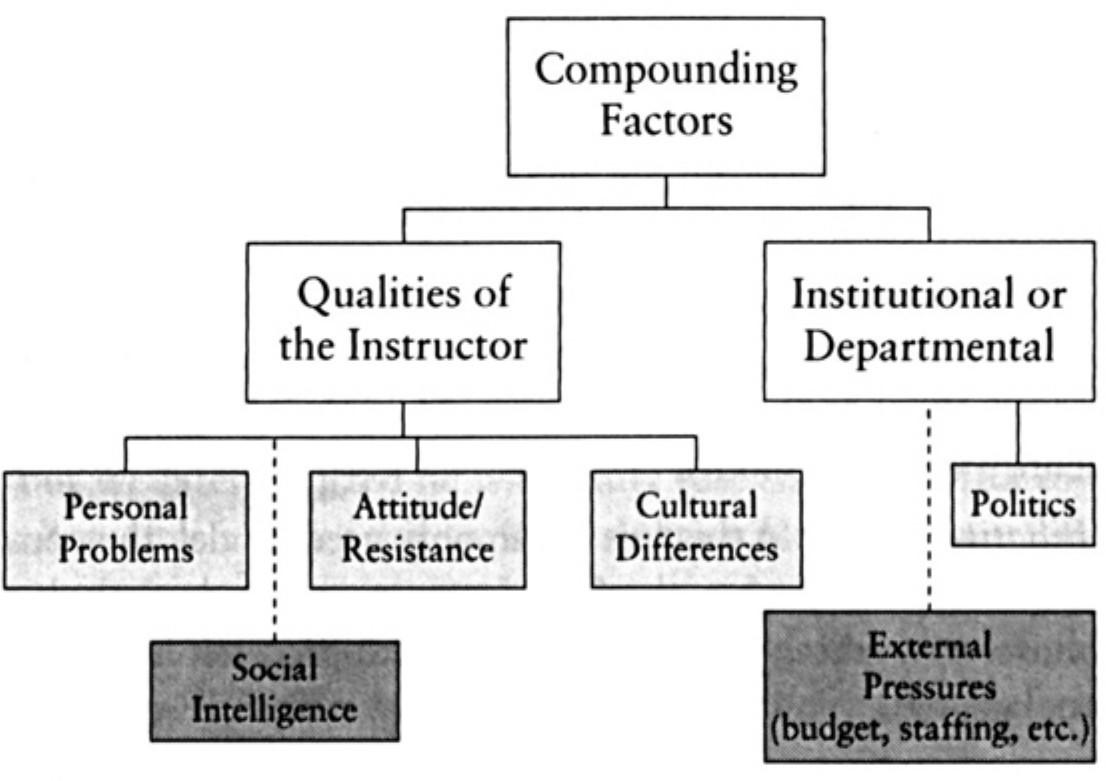

DiPietro and Huston (2009) offer a model of compounding factors that can help or complicate the course of consultations, identifying two main categories: qualities of the instructor and institutional or departmental factors. They identify issues such as personal problems, cultural differences, or a generally resistant attitude on the part of the instructor, and departmental or institutional politics, which can all work in some way to create what they call "entangled consultations," or those that are "layered with complexity" and "extend far beyond pedagogical questions" (p. 8).

Undoubtedly these factors that DiPietro and Huston identified are crucial to recognize when entering into difficult consultations. However, based on our own experiences as faculty developers, we believe that there are additional factors to include on the list, which we address here. Regarding instructor qualities, one important element to consider is lack of social intelligence, which Rosier (2011) describes as the ability to "understand what another person feels and act effectively and appropriately based on that understanding" (p. 75). Whereas she explores it as a factor related to teaching, our experiences also suggest that it can affect the consultation process.

Figure 8.1. Compounding Factors with an Impact on Consultations.Source: Adapted from DiPietro and Huston (2009).

Figure 8.1. Compounding Factors with an Impact on Consultations.Source: Adapted from DiPietro and Huston (2009).Beyond departmental or institutional politics, other pressures external to the instructor can complicate the consultation process. For instance, we have seen how budget or staffing concerns, or even time constraints and burgeoning departmental administrative responsibilities, can affect the ability to enact curricular change or remain open to the consultation process. (See Figure 8.1.) Indeed, many factors that can lead to resistance and impede the progress of a consultation, and multiple philosophies or styles, can inform the consultation approach.

Other Consultation Models

Several scholars have worked to identify consultation models that can help us as faculty developers define our own styles. Building on work from the fields of education, psychology, organizational behavior, and medicine, Brinko (1997) identified five consultation styles or patterns commonly shared by faculty developers:

Product model. The consultant is seen as the expert, and the faculty member, or client, is the seeker of that expertise. The client identifies the problem (for example, students are not reading their assigned materials), and the consultant produces a solution (for example, the instructor can give students formative quizzes at the start of class for accountability).

Prescription model. In this model, often seen in doctor-patient relationships, the consultant serves as the identifier or diagnoser of problems, while the client is the unquestioning receiver.

Collaborative or process model. A partnership is formed with the consultant operating as the "catalyst" or "facilitator of change" and the client as the content expert. Many faculty developers identify with this model.

A{filiative model. In this less commonly used model, the consultant serves in a combined role as instructional and psychological counselor, working with the client toward professional and personal growth.

Confrontational model. The consultant plays the role of challenger, particularly in situations in which he or she realizes that confrontation is necessary before real change can occur.

Little and Palmer (2011) describe a collaborative consultation strategy that combines careful listening, asking thoughtful questions, and encouraging action. In this expanded collaborative framework, consultants help to move instructors from one point to another or act as coaches, perhaps most powerfully by careful consideration of questions. Little and Palmer encourage faculty developers to focus on the difficult task of speaker-focused or deep listening and suggest the use of questions such as, "Which of your values are you honoring in this situation?" and "In what ways are you stuck?" The third component they recommend takes the questioning further by focusing on action. For example, consultants might pose questions such as, "What first steps will you take?" and, "How you will know that you are making progress toward these goals?"

In their article on "entangled consultations," DiPietro and Huston (2009) suggest employing the collaborative approach for tricky situations, and surely the work of Little and Palmer (2011) offers excellent supplementation to the collaborative model with their extended use of thought-provoking questions and careful listening. Our model builds on their identification of these complications in consultations by suggesting further steps to help us reflect on the "Now what?" conundrum we face when dealing with difficult consultations.

Difficult Consultations: Three Case Studies

Using three case studies, we explain and explore our approach and how it has worked for us in consultations. Permission was obtained from all participants, and for purposes of anonymity, the names and identifying details for each case study have been changed.

Our first case involves Dr. Jones, a third-year faculty member who had not involved himself with our teaching and learning center aside from attendance at a few scattered workshops. A large, loud man, he is an intimidating presence in the classroom. He came to our center for consultation, but we later realized he was really just checking off a to-do list given to him after a rocky third-year evaluation from his tenure and promotion committee. Although Dr. Jones’s self-perception is that he is one of the best teachers at the university, it became clear when we observed him that his overbearing ways have worn out their welcome with students and perhaps even his colleagues.

Our second case involves Jessica, a bright, third-year doctoral student. She expresses great interest in teaching and is familiar with some of the best practices and educational literature. However, her teaching evaluations remained low despite her hard work, and she came to us for assistance. As we got to know her, we realized that Jessica struggles with her social awareness and her ability to interpret and stay in tune with others’ feelings and perceptions. These social problems were taking a toll not only on her relationship with her undergraduate students, but also with her department faculty and graduate student colleagues and were also complicating the consultation process.

Our third case involves our work with a large, multidisciplinary course taught in one department in the College of Agriculture but required for students in another, vastly different department (from the College of Human Sciences). Consultants at our center had worked with several graduate student instructors from this course over several years, witnessing the same recurring problems but with little to no improvement or progress. Many of the problems that course instructors faced involved the palpable tension between the two departmental cultures. The course remained in control of the faculty member who designed and continues to oversee the course.

Our Model

We have found that a more direct approach is often called for in certain complicated consultation situations, whether it is an instructor in denial about the success of his class or a teaching assistant (TA) who does not seem to hear the feedback from her students and advisers. In these situations, we have begun implementing what we call the "provocative approach," which at its core involves having direct and assertive conversations. It is a consultation style that is perhaps slightly new and uncomfortable for many faculty developers, but it has foundations in the counseling literature and can be quite effective. The steps a faculty developer might consider in this model can be remembered using the mnemonic phrase, "Don’t Ever Call Sally A Loose Cannon":

Describe

Evidence

Cut in and call them out

Straightforward

Ask questions

Listen, language, like-minded

Compromise

The D in Don’t stands for describe the situation and explain the consequences. A common approach used to initiate discussion in a consultation is to ask the faculty member a series of simple but telling questions such as, "Was this a typical day?" "What usually happens in your classes?" and, perhaps most important, "What did you notice?" This is an opportunity for the faculty member to direct the conversation, and indeed, what he or she shares often reveals his or her comfort levels and openness to the consultation process. For example, when Dr. Jones met with the consultant and reflected on a recent class observation, he noted that he saw nothing of concern and thought it had been a great example of his teaching. Yet the consultant had noticed patterns of verbal dominance on the part of the teacher with minimal participation from students. These potential discrepancies alert the faculty developer and may be the first sign that the consultation could prove to be complicated. Asking simple, reflective questions also helps the faculty developer gain context for understanding the particular challenges facing the instructor and build a frame of reference, particularly if this is the first observation.

The E in Ever suggests that we explain the evidence, data, and research. Data and evidence play an important role in our consultation practices. We begin every teaching observation by creating a time line or factual record of the class and take extensive notes on the teaching techniques used, organization of content, student participation, and student behaviors such as attentiveness, note taking, and displays of distraction such as texting. We count the number of student questions, record the wait time, and pay attention to displays of teacher immediacy such as facial expressions and nonverbal communication. This time line often proves to be a significant conversation starter in our consultations as we ask the instructor to review the time line and comment. Often this data conversation opens the door to deeper reflection, particularly when led by the consultant through questions such as, "I noticed that students seemed to get restless after about twenty minutes. What do you think was going on? Did you see it?" Little and Palmer (2011) suggest that finding neutral ways to incorporate data into a consultation and combining this information with careful questions can help instructors hypothesize and reflect on their actions and student behavior.

For instance, when we realized that the graduate student instructors of the third case study were not sharing student feedback with the faculty members in charge, and consequently faced similar problems from year to year, we felt that being more direct with those with authority over the course and presenting them with the actual information on what we saw would make greater strides toward influencing change. Cook (2001) affirms the power of empirical data in reaching consensus and encouraging curricular reform. After receiving the permission of the graduate student instructors, we called a meeting with the course’s faculty adviser and the relevant department chair from the College of Human Sciences to share the prevalent patterns of student feedback collected over the years. Once presented with the data demonstrating the ongoing problems with the course, the faculty members were much readier to consider possible change.

Another hallmark of our consultation practices is to provide feedback steeped in teaching and learning research. We work hard to connect any comments we might make to established literature. We also try to make sure that the instructor leaves us with some kind of resource in hand, perhaps an article from the scholarship of teaching and learning literature or a link to a resource found on a teaching and learning Web site. Calling attention to the rich body of teaching and learning literature gives us credibility, even as we establish roles in collaborative consultations in which the faculty members are seen as experts of their discipline and the faculty developers play the role of facilitator (Brinko, 1997). With some faculty members and instructors, this extra step has built trust that paves the way for more difficult conversations later.

The C in Call encourages faculty developers to cut in and call instructors out when needed. Little and Palmer (2011) remind us that the difficulty and value of deep listening can be easily underestimated. It is all too easy to fall into a passive listening role or focus on our next statement or rebuttal, but we strive to maintain a speaker-focused or deep listening mode. Faculty developers operating in this mode, paying attention to what the speaker is communicating verbally and nonverbally, may find that they occasionally need to interrupt and confront their clients. For example, as the consultant worked in consultation with Jessica, the very bright but somewhat socially challenged graduate student, she realized after some time that she needed to work harder to intervene in the moment and help her identify patterns of behavior. In this case, the consultant’s role during confrontation should be one of puzzlement versus hostility (Hill, 2009). Perhaps the greatest challenge for faculty developers is finding the right strategies and words so that our clients do not feel attacked. Hill suggests that we adopt a quizzical, "What do you think?" attitude as we collaboratively work to talk through and clarify behaviors. During a discussion with Jessica about a frustrating classroom dynamic, the consultant interrupted her and said, "May I stop you for a moment? I noticed that you have been talking a little louder and faster, and your voice is higher. What do you think is going on? What are you feeling right now?" With this collegial confrontation and encouragement to examine herself, perhaps we can persuade her to see a new perspective.

The S in Sally reminds us to be straightforward and communicate directly, even though it is difficult. This element is perhaps the most challenging part of the approach for many faculty developers, especially those more accustomed to the give-and-take style of the favored collaborative approach. Many of us are trained in using qualifiers or softened language in our feedback, and we strive to demonstrate great respect for the vulnerability of the instructors who are seeking consultation. However, in our experience, directness need not undermine that respect and is frequently required in various forms to reach instructors who might be aggressive, inept at reading social cues, or generally resistant or in denial.

For faculty developers who struggle with assertive communication, the field of counseling psychology offers some useful strategies. Stephen Cook (2009) advises those attempting to communicate assertively to start with "I feel" statements because others cannot argue with personal emotions. Counseling literature also suggests making those direct statements about thoughts, feelings, and needs in a kind but firm fashion. Wood (2010) writes that "people who are assertive appear to be very confident because of their body language.... They maintain good posture and stand a little straighter ... their voices are relaxed, clear, and loud enough to be understood. And their eyes maintain regular contact with the other person" (p. 141).

For example, we found it to be more effective to communicate directly with Jessica because she was not adept at reading between the lines, and her listening skills were not strong. In stressful situations, her voice often became louder and shrill, and she would interrupt those around her, despite their clear exasperation with her behavior. Instead of letting her dominate group discussions or talk over others attempting to share student feedback with her, we tried pointing out her behavior patterns during consultation, saying things like, "Jessica, I feel that you are not listening when you interrupt and raise your voice." Since Jessica lacked the self-awareness to recognize this behavior, our directness proved to be quite beneficial for her, and she began to work on monitoring her listening behaviors and volume.

The A stands for ask questions about instructors’ assumptions, perceptions, and practices. Brinko (1997) and Little and Palmer (2011) discuss the value in presenting an instructor with questions about his or her assumptions and practices in the classroom, and the counseling literature (Hill, 2009; Wood, 2010) similarly discusses the occasional need to challenge clients by questioning discrepancies in their actions and beliefs. Instructor-focused, thought-provoking questions can help encourage instructors to reflect on their teaching and thereby promote change. Perhaps an instructor does not truly know why he has made certain decisions in the classroom, or perhaps she has not considered the implications or the inconsistencies in her actions. Dr. Jones, for instance, was surprised when asked about his discussions in class regarding current events. He claimed to value student participation and in fact asked many questions of his students to solicit their ideas. However, when the consultant pointed out and literally counted the number of rapid-fire questions he asked, he was surprised to see that students were literally left no time to respond.

Little and Palmer (2011) offer many useful examples of probing or challenging questions that can assist consultants in working with instructors to identify attitudes and point out potential discrepancies. Questions such as, "What do you think is really going on?" "Why does it matter to you?" and "What is another perspective you could have about this?" are simple yet effective in helping an instructor cull out underlying beliefs and potentially faulty assumptions that might be creating conflicts both in and outside of the classroom.

The L in Loose encourages consultants to listen closely and mirror an instructor’s language, as well as exercise empathy and courtesy. While directness and assertiveness are undeniably important, so is using our own social intelligence skills by demonstrating empathy, deep listening, and taking cues from the instructor. Remaining sensitive to the instructor’s needs and staying in tune with his or her individual personality can be especially powerful in difficult consultations. For instance, when working with the aggressive and brisk Dr. Jones, the consultant realized that "speaking his language" and using his own words would have the most impact. Therefore, in the consultation, when he said, "So I just need to shut up," she responded in kind by saying, "Yes, I think you need to shut up." Those words meant something to him, and it was a light bulb moment.

Conversely, when working with Jessica, a more sensitive young woman, we were sure to acknowledge her strong desire to see her students succeed as we tried to help her recognize the disconnect she had with them. We would never say "shut up" to Jessica, because she would never use those words and would find them insulting. We might instead show respect for her efforts and knowledge by saying something like, "You know how important it is to have a good relationship with your students," and then direct her toward the feedback that highlights the disconnect. And similarly, we knew that by offering years of quantitative and qualitative data based on self-generated student feedback, we would be speaking the language of the faculty in charge of the large, science-based, interdisciplinary course.

Social work literature provides some examples of leads for empathic responses that we can use in the consultation process. Rohdieck (2007) sug- gests starting with questions such as, "Could it be that you are feeling ... ," "What I’m hearing is ... ," or "To me, it’s almost like you’re saying ... " It is important to have a rich vocabulary and consider the power of words that we use. In all three of the case stories, the use of empathy and like-mindedness softened the potential awkwardness and directness of the other questions we were asking and the issues_ we were raising.

Finally, the C in Cannon reminds us to be willing to compromise and negotiate as needed, even asking the instructor for alternative solutions when necessary. The counseling literature similarly advises "turning the tables" and turning the problem over to the instructor or "client" (Linehan, 1993). If the instructor is struggling with the idea of making changes, it can be beneficial to be flexible and ask, "How do you think it would be best to approach this problem?" As Hodges (2006) suggests, perhaps fear is an issue, and finding answers or solutions that are simple, minimally intrusive, or "doable on a small scale with a good chance of success," especially those solutions an instructor devises, can offer greater chance for openness to change (p. 131 ).

In the multidisciplinary course, for example, we worked with the faculty members to devise just a few simple changes as a beginning. Rather than suggesting wide-scale curricular revision, we started with suggesting smaller classes that divided the majors and nonmajors and offering a section of the course on campus that was physically more accessible to the nonmajors. These solutions were not threatening and emanated from the instructors themselves, and while they were perhaps not going to solve all of the problems of the course, they were a reasonable starting point and more easily implemented.

Evaluating Effectiveness

Development and progress take time. When developers adopt a more direct consultation style, one might wonder what happens to the trajectory of the consultation relationship. The outcomes of the three case studies highlighted here provide insight into the merit of this provocative consultation approach.

In the case of Dr. Jones, we realize that we have just begun a relationship with him. He is certainly intimidating, but our institution invested in him by bringing him in as a new faculty member, and everyone loses when the tenure process goes awry. We want to see him connect with students and with his colleagues, and after following up with him about his experiences with our consultation services, he said:

After talking to you I started paying more attention to what I was doing in class and started to make conscious decisions to get more from the students. I found the think-pair-share, and the reframing of my questions in class (going from "Any questions" to "What questions do you think my prior class asked about this") has increased class participation [person3l communication, October 12, 2011].

Although Dr. Jones’s comments could be easily dismissed, we interpret them as small steps and movement in a positive direction. In fact, Dr. Jones invited us back into his classroom to continue our observations and interview his students about their learning. Clearly the direct approach did not impede our relationship with him and helped him begin to make some important realizations about his teaching.

Jessica also experienced positive growth as a result of this provocative consultation approach. One of her faculty advisers communicated to us that the increased directness with Jessica "helped them get along" and worked to improve their relationship (personal communication, October 18, 2011). Another of Jessica’s advisers noted that our work With her "took a huge weight off of her shoulders" because she was "at a loss" about how to communicate with her (personal communication, October 18, 2011). Both mentors felt confident guiding her in discipline-specific matters but struggled with knowing how to approach her egocentrism, awkward discussion patterns, and misunderstanding of social cues (Rosier, 2011). Jessica had an "aha" moment midway through our work with her during a painful conversation about her social intelligence; she revealed that although others had pointed out her awkwardness, they never explained that awkwardness directly or helped her devise tangible strategies for more effective communication and interpreting social cues. Perhaps Jessica’s most important strength, and one that might make her unique among others struggling with social intelligence, was her eventual recognition of her problem and desire to change.

Our direct approach also seemed to be the key in making a difference with the interdisciplinary course. After a meeting with key faculty from both departments and a review of the data, these faculty members grew excited and even began looking into potential new classrooms on campus for the following semester. Unfortunately, departmental compounding factors (DiPietro & Huston, 2009) got in the way during a difficult year. The course adviser became department chair and faced an overwhelming number of new responsibilities. The economy also went sour, and budgets were cut, leaving no room to pay a second instructor to teach the course or to pay one instructor to teach a second section. Both departments still communicate interest in implementing those basic changes, but it is clear that it will take some time (personal communication, September 21, 2011). Ultimately our direct approach instigated conversations about the course that we hope will continue.

Conclusion

The practice of consulting with faculty is undoubtedly complicated, especially when individual personalities and issues beyond the classroom come into play. It would be nice if consultations always went smoothly, or if we could use the same approach with everyone, but that is not the case. It is important to note that the provocative approach might be inappropriate for sensitive or timid instructors, or those who might be facing a mountain of other difficult circumstances. Furthermore, consultants could modify this approach to meet individual needs or even change consultation methods, adopting a more or less direct approach as a relationship develops and layers are revealed.

We do not claim to have all the answers for dealing with every difficult situation, but we think that this practice of occasionally stepping out of our comfort zones and adopting a more direct style when needed might at least fill in another piece of the puzzle. This might mean pointing out inappropriate behaviors, presenting convincing data, or simply asking thought-provoking, frank questions. Faculty developers know that one size does not fit all when it comes to consultations. The provocative approach can offer one more option for advancing the consulting relationship.

References

- Brinko, K. (1997). The interactions of teaching improvement. In K. Brinko & R. Menges (Eds.), Practically speaking (pp. 3-8). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Cook, C. (2001). The role of a teaching center in curricular reform. In D. Lieberman & C. Wehlburg (Eds.), To improve the academy: Resources for faculty, imtructional, and organizational development, Vol. 19 (pp. 217-230). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Cook, S. W. (2009). Communicating assertively. Lubbock: Texas Tech University, Department of Psychology.

- DiPietro, M., & Huston, T. (2009). A theory and framework for navigating entangled consultations: Using case studies to find common ground. Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, 1, 7-37.

- Fletcher,J., & Patrick, S. (1998). Not just workshops anymore: The role of faculty development in reframing academic priorities. International Journal for Academic Development, J(l), 39-46.

- Hill, C. E. (2009). Helping skills: Facilitating exploration, insight, and action (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Hodges, L. (2006). Preparing faculty for pedagogical change: Helping faculty deal with fear. In S. Chadwick-Blossey & D. R. Robertson (Eds.), Tt, improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional,and organizational development, Vol. 24 (pp. 121-134). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Linehan, M. (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Little, D., & Palmer, M. S. (2011). A coaching-based framework for individual consultations. In J. Miller & J. Groccia (Eds.), Tt, improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development, Vol. 29 (pp. 102-115), San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Lucas, A. F. (2001). Reaching the unreachable: Improving the teaching of poor teachers. In K. H. Gillespie, L. R. Hilsen, & E. C. Wadsworth (Eds.), A guide to faculty development: Practical advice, examples, and resources (pp. 167-179). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Rohdieck, S. (2007). Using the helping process to strengthen our consultation skills. Paper presented at the 31st annual meeting of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, Portland, OR.

- Rosier, T. (2011). There was something missing: A case study of a faculty member’s social intelligence development. In J. Miller & J. Groccia (Eds.), Ti, improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development, Vol. 29 (pp. 74-88). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/ Anker.

- Smith,J., & Smith, S. L. (2001). Promoting active learning in preparing future faculty. In K. Lewis & J.P. Lunde (Eds.), Face to face: A sourcebook of individual consultation techniques for faculty/instructional developers (pp. 313-329). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Turner, J., & Boice, R. (1986). Coping with resistance to faculty development. In M. Svinicki, J. Kurfiss, & J. Stone (Eds.), Ti, improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development, Vol. S (pp. 26-36). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Wood, J.C. (2010). The cognitive behavioral therapy workbook for personality disorders. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Zahorski, K. (1993). Taking the lead: Faculty development as institutional change agent. In D. Wright & J. Lunde (Eds.), Ti, improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development, Vol. 12 (pp. 227-245). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.