16 Developing and Renewing Department Chair Leadership

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Most faculty development centers offer limited resources for leadership development, and most existing programs focus on training the new chair. The key questions we address are: What role do teaching centers play in administrative professional development? How can we develop programs that assist new chairs with their immediate questions, while also promoting continued growth in institutional leadership? We present one model at the University of Michigan, initiated by the provost and organized by the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, which involves an extensive needs assessment process, a developmentally oriented leadership training program, and an evaluation.

Department chairs play a key role in faculty development. They are well-positioned to help individual faculty develop their teaching, research, and service capacities; facilitate departmental effectiveness; and work with upper-level administrators to carry out the university’s mission (Cuban, 1999; Feldman & Paulsen, 1999; Hecht, 2000; Hecht, Higgerson, Gmelch, & Tucker, 1999; Lucas, 1990; Rice & Austin, 1990; Sorcinelli, Austin, Eddy, & Beach, 2006; Walvoord et al., 2000). The benefits are also reciprocal: department heads who feel that they are effective faculty developers are more likely to stay longer in the position (Seagren, Creswell, & Wheeler, 1993).

However, many challenges exist for chairs in their roles as faculty developers. Given the intensity of the workload and frequently the short tenure of the position, many chairs often just do not have time to focus on pedagogical issues. Many of them report that in spite of their intention to improve the quality of teaching in a department or build a “culture of teaching,” they are unsuccessful at doing so (Lucas, 1989; Wright, 2008). Therefore they often perceive themselves as being more supportive of faculty than do the faculty themselves (Whitt, 1991). Clearly, institutions need to ensure that this key administrative role is functioning most effectively.

In 1986, Lucas documented that little chair training was taking place in higher education, with a few notable exceptions (for instance, American Council on Education, University of Tennessee, Michigan State University, and Kansas State University). Unfortunately, both our benchmarking (described later) and the literature confirm that little has changed (Lucas, 2002). Furthermore, existing programs focus primarily on new chair audiences, especially on managerial skills to help academic leaders with the immediate faculty-chair role transition.

The paucity of ongoing chair training raises several questions. First, is there an unmet need for programming inclusive of more experienced chairs? If so, are there key differences in the training needs of new and experienced department heads? How can instructional developers encourage continued growth and leadership potential in chairs? Finally, what are effective and efficient ways of organizing this programming, and who should be facilitating it?

In this chapter, we present a model for a developmentally oriented chair training program organized by the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT) at the University of Michigan. The University of Michigan is a large research university, with nineteen schools and colleges. Every year, approximately thirty faculty become new chairs, and because of these recurring transitions the provost invited CRLT to design a new program. Its success stems not only from the design we describe here but also from her support and participation.

Because faculty developers have not prioritized training for department leaders (Sorcinelli et al., 2006), we begin with a discussion about how teaching centers can facilitate (and benefit from) such initiatives. We then present a model for development of a leadership program, beginning with a needs assessment that identifies the difference in perspective among new and experienced chairs, faculty, and deans. Drawing on our needs assessment findings, we describe a model for a developmental program that not only assists new chairs with their immediate (“hit the ground running”) questions but also promotes their continued growth in institutional leadership skills. Finally, we describe the evaluation process and findings that CRLT used to judge the effectiveness of the program. This three-part model focuses on how faculty developers can facilitate the transition from faculty to chair, as well as ongoing administrative leadership skill development.

The Role of Teaching Centers in Chair Training

As with any university program, the first question we had to address was, Who will initiate the program? The Offices of the Provost and Human Resources (HR) are the most common locations for chair training programs. Although the University of Michigan provost’s office initiated the program development process, we felt it was strategic to locate the program in CRLT, the university’s teaching center—a departure from most other chair training programs. (A notable exception is Michigan State University, where the Office of Faculty and Organizational Development, which reports to the head of HR, runs the New Administrator Orientation.) Perhaps faculty development centers have not prioritized training for department leaders because they have not been given the opportunity (Sorcinelli et al., 2006).

Hecht (2000) argues that faculty developers can play a key role in supporting department chairs during their individual development from managers to leaders. Indeed, for other institutions considering an administrative leadership program, we note that this institutional location yields several organizational benefits.

First, teaching centers are usually part of the provost’s office, thereby connected to the administration’s current initiatives and familiar with the key issues facing the university. Because of its organizational location, a center can focus a training program on topics of special interest to the provost, and it can make connections to relevant university speakers.

Second, teaching centers routinely plan programs for various groups of faculty, so they are adept at interacting well with faculty and handling logistics. Instructional consultants know how to plan engaging programs that incorporate active learning strategies. They also know how to conduct programming that brings together faculty from many units to discuss interdisciplinary topics.

Third, and especially important for a developmentally oriented administrative leadership program, center staff members often play an interstitial role themselves. They work closely with individual faculty by providing new faculty orientations, consulting with them about their pedagogy and course design, serving their needs in center programs and workshops, and reviewing their grant applications. They also collaborate with decanal offices by helping to design curricular reform, facilitating retreats and meetings, and strategizing ways to evaluate and reward good teaching.

The advantages extend to the center as well. As Lucas (2002) notes, “Staff in faculty development centers can significantly increase their effectiveness in higher education by gaining access to academic departments and teaching chairs to promote faculty development” (pp. 158–159). Department chairs are often the missing link in the outreach and work of a center. The training serves to connect chairs with the center; chairs meet center staff and are therefore more likely to call on them for their own programming or curricular evaluation and redesign in the future. Likewise, through informal discussions during the programs, center staff members can learn about departmental needs and offer services responsively. They may also be able to weave some teaching and learning topics into the programs for administrators.

Needs Assessment Design and Findings

Other research has documented key elements of chair training programs (for example, Lucas, 1986), but a thorough needs assessment was the key to understanding what University of Michigan chairs and deans sought in a local initiative. The needs assessment was especially important because two previous attempts to establish a chair training program had proven to be unsuccessful and were discontinued after only one year. Our assessment had three stages: (1) a benchmarking study of peer institutions, (2) interviews with successful chairs, and (3) a focused survey of new chairs, experienced chairs, faculty and deans, which asked them to rank topics for a program. (This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.)

Benchmarking

CRLT began by researching what the university’s peer institutions were doing for chair or leadership development. A Web search, performed in 2006 and again in 2008, for “department chair training or orientation programs” discovered several training programs at community colleges across the nation, as well as a host of programs not affiliated with educational associations (for example, the Department Leadership Programs offered by the American Council on Education and the Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology leadership training). However, we found very few department chair preparation programs at large universities.

Because in many cases internal programs such as chair training may not be advertised on the Web, we also surveyed colleagues at peer universities via email to determine if their institutions offered chair training programs. This informal survey of eighteen Big Ten and Ivy League Universities confirmed that most institutions had no centralized training program for new chairs. Notable exceptions are Cornell, Michigan State, Minnesota, Ohio State, Penn State, the University of Chicago, and Wisconsin. However, all of these programs focused primarily on new administrators.

According to our Web search and informal survey, most Big Ten and Ivy Plus institutions offer some form of support for new chairs, though this support often takes the form of written resources only (for instance, extensive resource websites for chairs at Princeton University), or it is restricted to certain units. Although more localized programs do have some advantages, a universitywide program would best encourage networking across departments and between new and experienced administrators.

Interviews with Experienced Chairs

Next, one of the authors conducted interviews with fifteen experienced chairs to identify the issues of particular concern to them and to obtain advice about an orientation and training for new chairs. The interviewees, six women and five faculty of color, represented the humanities, social sciences, sciences, quantitatively oriented fields, and professional schools. They were recommended by University of Michigan associate deans as effective departmental heads.

The new chairs universally responded with enthusiasm for a program. They talked about how the absence of an orientation had led them to seek advice from books and articles before assuming their administrative roles. However, even experienced administrators saw benefits to a training program. They endorsed the opportunity to network with their peers across disciplinary boundaries, as well as to share ways to address common issues and challenges.

In addition, chairs reacted to a list of potential topics drawn from the literature on department chair tasks, such as responsibilities related to departmental governance, faculty, budgeting, office management, curriculum, student issues, facilities management, data management, and communication with external constituencies (Hecht et al., 1999; Lucas, 1986). Out of this list, they recommended integrating several topics into the training: working with the department’s key administrator, setting a vision and developing a strategic plan, working with the dean, and understanding the university. However, beyond these instrumental tasks, chairs also advised that the program prioritize collegial interaction, or topics such as effective communications, department climate, mentoring faculty, tenure and promotion, and conflict resolution. For example, one head noted that when he started his new role he thought it was about managing the budget, but he quickly learned that the job was about managing people.

Surveys

The next step in the needs assessment was to survey new chairs (defined as those who started the chair position in the current calendar year), experienced chairs, faculty of various ranks, and deans. (Key administrators, the senior staff person in academic departments, also received surveys, but these results are not presented here.) We purposively selected survey recipients from university lists of each population to get a broad spectrum of disciplines and perspectives. Table 16.1 displays the response rates. Respondents were asked to select the seven most important orientation and training topics from a list of fourteen: communicating with colleagues and running meetings; evaluating and improving teaching; managing budgets; managing conflict and dysfunctional dynamics; managing the workload; mentoring faculty; understanding the organization of the university; handling searches, hiring, and position requests; setting a vision and developing a strategic plan; space planning; managing tenure and promotion issues; understanding the university’s financial picture; working with the dean; and working with a key administrator.

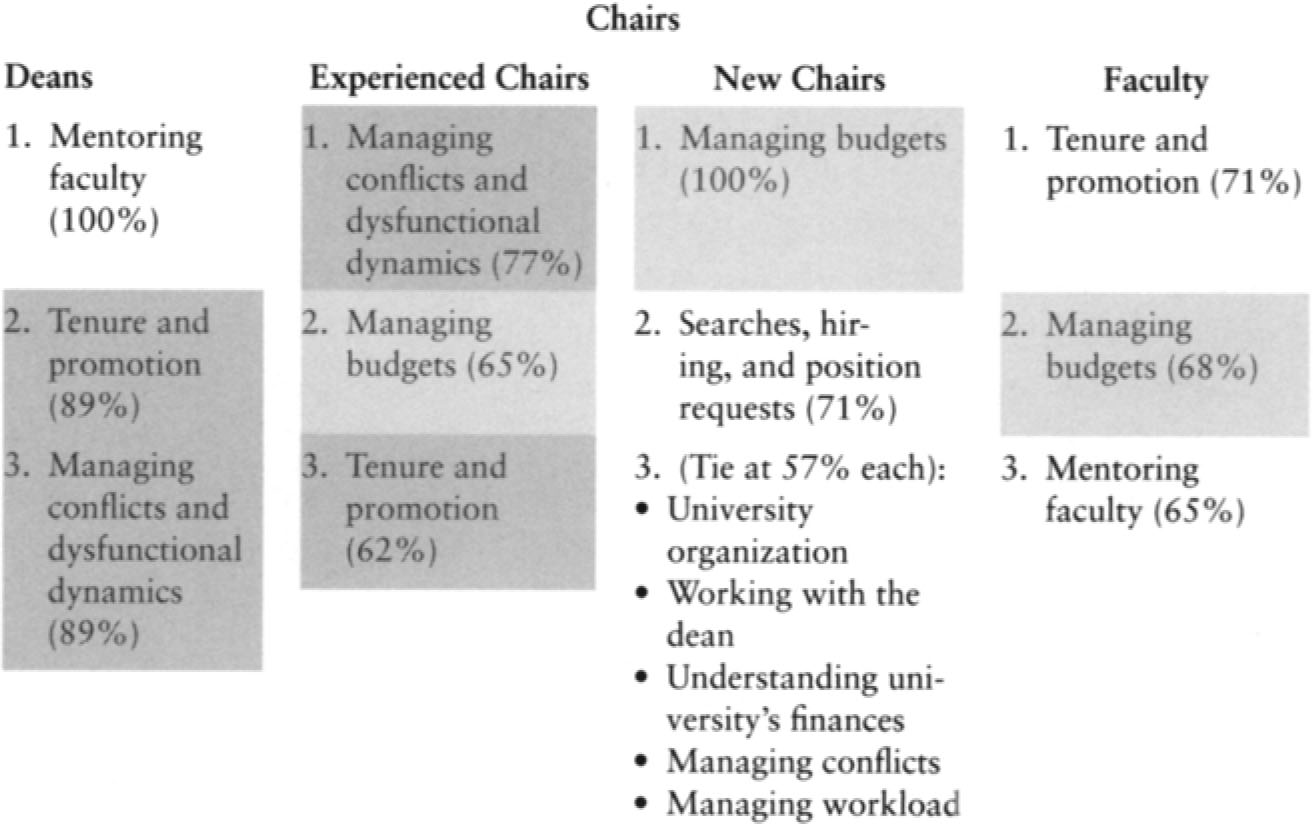

Interestingly, experienced administrators reported needs that differed from those of the new chairs. The new chairs’ requests for programming were primarily instrumental, focusing especially on such organizational issues as managing budgets and academic hiring processes (see Table 16.2).

| Survey Population | Survey Numbers and Response Rate |

|---|---|

| New chairs | 8 out of 11 responded (73%) |

| Experienced chairs | 25/38 (66%) |

| Faculty | 35/125 (28%) |

| Deans | 10/20 (50%) |

After these top two priorities, these new administrators showed much less consensus. In contrast, experienced chairs prioritized more affectively oriented training: conflict management and interpersonal dynamics, and then tenure and promotion (human capital management). They also agreed with new chairs, though less strongly, on the importance of fiscal management (65 percent compared to 100 percent). In summary, our results confirm Hecht’s comment: “While new chairs are particularly concerned about task mastery, the truth is that the attitudinal adjustments are the ones most important for chairs to make if they are to become effective leaders” (2000, p. 30). She notes that some of these key adjustments include the chair’s thinking about managing human relationships, time, and articulation of purpose.

In addition to surveying new and experienced chairs, we also asked faculty and deans to rank topics. Table 16.3 shows the congruence between rankings of faculty and chairs (highlighted in light gray) and deans and chairs (highlighted in dark gray). The priorities of experienced chairs significantly overlapped with those of both deans and faculty. For example, deans and experienced department heads shared tenure and promotion, as well as conflict management, as top priorities. Likewise, experienced chairs and faculty shared tenure and promotion and budget management as key priorities. This finding suggests that experienced chairs have learned to be effective liaisons between higher-level administration and faculty. The literature has identified this “conduit” role (Lucas, 1986, p. 112)—communication between deans and faculty—as being particularly important for successful chairs (Murray & Stauffacher, 2001; Walvoord et al., 2000).

In contrast, new chairs’ rankings overlapped some of those of faculty (managing budgets) and experienced chairs (managing budgets and conflict management), but there was no alignment with deans’ priorities. In other words, new chairs were not yet able to straddle the perspectives of both faculty and experienced chairs, perhaps because they still had one foot in the faculty role and the other in their new administrative responsibilities (Hecht, 2006).

| Experienced Chairs | New Chairs |

|---|---|

| 1. Managing conflicts and dysfunctional dynamics (77%) | 1. Managing budgets (100%) |

| 2. Managing budgets (65%) | 2. Searches, hiring and position requests (71%) |

| 3. Tenure and promotion (62%) | 3. University organization; working with the dean; understanding university finances; managing conflicts; managing workload (tie at 57% each) |

Table 16.3. Comparison of Ranking of Topics by Deans, New Chairs, Experienced Chairs, and FacultyNote: Overlap of deans’ and chairs’ rankings is highlighted in dark gray, while overlap of faculty and chairs’ rankings is highlighted in light gray.

Table 16.3. Comparison of Ranking of Topics by Deans, New Chairs, Experienced Chairs, and FacultyNote: Overlap of deans’ and chairs’ rankings is highlighted in dark gray, while overlap of faculty and chairs’ rankings is highlighted in light gray.Overall, these rankings indicate the need for a developmentally oriented chair training program. A comparison of new and experienced chairs shows key differences in needs relative to seeking immediate, instrumentally oriented programming, in comparison to development around retention and management of human resources. Also, the survey findings document the progression of training needs, from the faculty-chair role transition to the move through higher administrative ranks.

Program Development and Structure

Given the need for chair professional develo pment, how did the University of Michigan create a developmentally oriented program? In this section, we describe many aspects of the program-development process. The primary objectives of the program meetings were to encourage networking across administrative levels and the university and to engage administrators in topics that they indicated were important to their own professional development.

The needs assessment pointed to two requirements of the new program. First, new chairs had specific immediate training needs, which should be addressed in order to develop self-efficacy in their position. Second, experienced chairs also had training needs, but they sought programming around managing departmental dynamics. Therefore, CRLT developed two programs: an orientation for new chairs and an ongoing Campus Leadership Program for administrators of all experience levels. (An orientation for new associate deans was also developed, but this program is not described here.)

New Chair Orientation

A one-and-a-half-day program at the beginning of the academic year focused on getting new chairs up and running in their position. The first day, an evening program, began with welcoming remarks from the provost and ended with an interactive theater sketch on mentoring faculty.

The second day opened with a Q&A session with the university’s president. Next, the provost spoke about administrative roles in higher education, such as the stewardship responsibility of the chairs and the interface between the central administration and the university’s schools and colleges. Another interactive theater sketch triggered discussions about productive staff relationships. During lunch, very brief presentations addressed an assortment of topics: faculty searches and offers; faculty, staff, and student worklife assistance programs; ways to work with the campus’s lecturer and teaching assistant unions; and legal issues. A panel of deans focusing on what makes for a successful chair led into smallgroup case-study discussions about a faculty member who wants to spend all of his time on research, and faculty dissensus about the rationale for a new hire. The busy day ended with a session on budgeting.

At the event, new chairs were invited to the Campus Leadership Program (to be described), where they could interact with more experienced chairs and administrators. In addition, there was a final lunch, late in the academic year, for the new chairs to check in about their first year in the role.

Campus Leadership Program

All chairs and associate deans were invited to participate in an ongoing leadership development program consisting of six meetings during the academic year. The provost or vice provosts attended most sessions as well. These sessions aimed to encourage horizontal and vertical networking, as well as engage administrators in topics that they indicated were important to their own professional development (see Table 16.4).

Program Evaluation

To refine the program, we included an evaluation in the program development process. We used attendance and participant self-reports of the programs’ utility, as measured through a survey, to assess the New Chair Orientation and the Campus Leadership Program. Our first measure, attendance, identified that the topics resonated with our campus administrators. Most new chairs and associate deans, and a plurality of experienced chairs, attended at least one event (see Table 16.5). A significant proportion of these administrators also attended multiple events.

For individual sessions, attendance data indicate that the role-specific orientation sessions were effectively targeted. A majority (21/30) of new chairs and almost half (28/68) of associate chairs attended the orientation programs geared to their roles (see Table 16.6). The session Dealing with Difficult People was by far the best-attended; it seemed to resonate with administrators at all levels. Sessions on conducting searches and department meetings, as well as a final new-chair gathering, were the least attended, likely because of competing events at the university.

CRLT also surveyed the participants to identify the program’s strengths and to gather suggestions for next year. The survey (two rounds) went to all chairs (new and experienced) and associate deans who attended at least one of the Campus Leadership Programs. Fourteen new chairs (a 56 percent response rate), nineteen experienced chairs (a 37 percent response rate), and eight associate deans (a 19 percent response rate) completed the survey. The questions were: (1) Which event(s) did you find the most useful, and why? (2) Do you have suggestions for changes for next year’s Provost’s Campus Leadership Programs? and (3) The provost initiated these Campus Leadership Programs; is there any message you want us to give her about them?

| Month | Topic |

|---|---|

| October | Assessment of faculty performance |

| November | Conducting searches and running faculty meetings (interactive theater) |

| December | Accreditation |

| January | Dealing with difficult people (workshop by Gunsalus, 2006) |

| February | Methods for evaluating and improving teaching |

| March | Developing and carrying out a vision for the department |

We found the key findings very gratifying. First, certain sessions evoked praise. The new chairs found the fall orientation to be a particularly helpful source of information, and everyone appreciated Dealing with Difficult People. Combined with the attendance data, these findings suggest that these topics should be continued in any future programming. Second, all the chairs and associate deans highly evaluated the orientation and roundtables as important networking resources, enabling them to meet colleagues and share strategies around common challenges. Because this reflected one of CRLTs objectives for these events, we were gratified by the reaction. Third, almost every respondent described the programs as valuable and thanked the provost for offering them. Because chair training was her initiative, she was highly visible at many of the meetings. We hoped to have her take credit for the initiative, and we appreciated that respondents did so.

| Number Attending at Least One Event | Number Attending at Least Two Events | |

|---|---|---|

| New chairs (30 total) | 25 (85% of all new chairs) | 20 (66% |

| Experienced chairs (121) | 51 (42%) | 21 (17%) |

| Associate deans (68) | 43 (63%) | 29 (43%) |

| Topic | Attendance |

|---|---|

| New chair orientation | 21 |

| Assessment of faculty performance | 43 |

| Conducting searches and running faculty meetings (interactive theater) | 14 |

| Accreditation | 28 |

| Dealing with difficult people (Gunsalus, 2006) | 60 |

| Methods for evaluating and improving teaching | 29 |

| Developing and carrying out a vision for the department | 38 |

| Final reception for new chairs | 11 |

| Associate dean orientations | 28 |

The suggestions for improvement helped us with program refinement. First, we found that these busy administrators preferred programs that were specific and practical, in contrast to theoretical and abstract topics. Second, we learned that the associate deans wanted much of the same training as what the chairs received, so in the program’s second year we invited both groups to the same orientation and monthly programs. This format enhanced opportunities for networking, and the chairs were pleased that the associate deans had a chance to hear about the special challenges faced by department chairs.

Conclusion

This chapter has described a three-step model for teaching centers to construct a developmentally oriented administrative leadership program: (1) a needs assessment, (2) program implementation, and (3) useful evaluation. This model fills a gap in programming for ongoing leadership support. For other institutions that wish to initiate a developmentally oriented leadership program, we have four suggestions.

First, think strategically about how to build a sustainable program that will be attractive to a diverse group of chairs. To develop programs that speak to the realities of your campus and to those in different administrative stages, a thorough needs assessment is essential. Likewise, collect evaluation data during and after the program to demonstrate the value of continuation and glean useful suggestions for improvement.

Second, plan carefully about how to attract attendees, considering the busy lives of academic administrators. It is important to limit the time commitment required for the programs and to get complete buy-in from upper-level administration. Busy department heads will not make time for professional development unless upper-level administration has given its imprimatur. We believe it critical that our provost recommended the programs to the deans (to then recommend to chairs) and was visible at the events.

Third, integrate networking opportunities among administrators, vertically and horizontally. This practice encourages formation of informal support groups that further encourage professional growth across the administrative spectrum.

Finally, consider the important role that your center has to play in organizing a chair training program. A teaching center can facilitate highquality professional development for administrators while also increasing campus receptivity to instructional improvement. Specifically, it can help chairs understand and execute their important role as “faculty developers” in their department, helping faculty balance their teaching with their other university responsibilities.

References

- Cuban, L. (1999). How scholars trumped teachers: Change without reform in university curriculum, teaching, and research, 1890–1990. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Feldman, K. A., & Paulsen, M. B. (1999). Faculty motivation: The role of a supportive teaching culture. In M. Theall (Ed.), New directions for teaching and learning: No. 78. Motivation from within: Approaches for encouraging faculty and students to excel (pp. 71–78). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Gunsalus, T. (2006). The college administrator’s survival guide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hecht, I.W.D. (2000). Transitions and transformations: The making of department chairs. In D. Lieberman & C. M. Wehlburg (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 19. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 17–31). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Hecht, I.W.D. (2006). Becoming a department chair: To be or not to be. Effective Practices for Academic Leaders, 1(3), 1–16.

- Hecht, I.W.D., Higgerson, M. L., Gmelch, W. H., & Tucker, A. (1999). The department chair as academic leader. Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education and Oryx Press.

- Lucas, A. F. (1986). Academic department chair training: The why and how of it. In M. Svinicki (Ed.), To improve the academy: Vol. 5. Resources for student, faculty, and institutional development (pp. 111–119). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Lucas, A. F. (1989). Motivating faculty to improve the quality of teaching. In E. C. Galambos (Ed.), New directions for teaching and learning: No. 37. Improving teacher education (pp. 5–16). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lucas, A. F. (1990). The department chair as change agent. In P. Seldin & Associates, How administrators can improve teaching: Moving from talk to action in higher education (pp. 63–88). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lucas, A. F. (2002). Increase your effectiveness in the organization: Work with department chairs. In K. H. Gillespie, L. R. Hilsen, & E. C. Wadsworth (Eds.), A guide to faculty development: Practical advice, examples, and resources (pp. 157–166). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Murray, J. W., & Stauffacher, K. B. (2001). Departmental chair effectiveness: What skills and behaviors do deans, chairs, and faculty in research universities perceive as important? Arkansas Educational Research and Policy Studies Journal, 1(1 ), 62–75.

- Rice, R. E., & Austin, A. E. (1990). Organizational impacts on faculty morale and motivation to teach. In P. Seldin & Associates, How administrators can improve teaching: Moving from talk to action in higher education (pp. 23–44). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Seagren, A. L., Creswell, J. W., & Wheeler, D. W. (1993). The department chair: New roles, responsibilities and challenges (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1 ). Washington, DC: George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

- Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., Eddy, P. L., & Beach, A. L. (2006). Creating the future of faculty development: Learning from the past, understanding the present. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Walvoord, B. E., Carey, A. K., Smith, H. L., Soled, S. W., Way, P. K., & Zorn, D. (2000). Academic departments: How they work, how they change (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 27[8]). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Whitt, E. J. (1991). Hit the ground running: Experiences of new faculty in a school of education. Review of Higher Education, 14(2), 177–197.

- Wright, M. C. (2008). Always at odds? Creating alignment between administrative and faculty values. Albany: SUNY Press.