Chapter 3 Maturation of Organizational Development in Higher Education

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Organizational development (OD) is fundamentally about increasing institutional capacity for change. Organizational culture is a pivotal variable mediating the success of institutional change initiatives. Faculty and OD professionals are poised to address the need for increased understanding of organizational culture and change in higher education institutions. This chapter presents a conceptual guide to theories of change and cultural analysis that inform OD practice. Distinctions between content and process theories of change, as well as normative and idiomatic approaches to cultural analysis, are reviewed with respect to their utility for facilitating change in the academy. Implications for the maturation of OD in higher education are discussed.

Organizational development (OD) is fundamentally about increasing institutional capacity for effecting change—change in individuals, in organizational units, and in institutional strategic direction (Bennis, 1969; Warzynski, 2005). The need for effective leadership of organizational change has become a preoccupation of academic administrators throughout the higher education community (Astin & Astin, 2000; Gayle, Tewarie, & White, 2003; Kellogg Commission, 2006). Increasingly, academic support units working to promote faculty development within the academy are being called on to respond to the need for internal facilitators of organizational change (Blackwell & Blackmore, 2003; Chism, 1998; Diamond, 2005; Ruben, 2005). Understanding and managing organizational culture has emerged as a pivotal issue in ensuring the success of these organizational change efforts (Eckel & Kezar, 2003; Kezar & Eckel, 2002; Latta, 2006). Mastering the skills and techniques of assessing organizational culture and managing change have become essential components of the knowledge base for individuals responding to the demand for assistance planning and facilitating OD in academic institutions.

New Roles for Faculty Developers

The need to increase institutional capacity for effecting successful organizational change is helping define new roles for individuals working in academic support units to foster faculty development in the academy (Blackwell & Blackmore, 2003; Chism, 1998; Diamond, 2005; Frantz et al., 2005; Patrick & Fletcher, 1998; Warzynki, 2005). Traditionally focused on enhancing individual skills for teaching and learning, these units are being called on to expand the scope of their services to encompass all areas of institutional mission in support of broader strategic goals (Chism, 1998; Ruben, 2005). Individual faculty development efforts are giving way to opportunities for working with intact academic units (Dwyer, 2005; Latta & Myers, 2005), targeted administrative groups such as department chairs (Austin, 1994; Yen, Lang, Denton, & Riskin, 2004), leadership development initiatives (Turnbull & Edwards, 2005), and senior planning teams (McLean, 2005; Warzynski, 2005). The intent of these efforts extends beyond attention to immediate results, to address the strategic goals of developing future leadership capacity and supporting long-term institutional objectives (Chesler, 1998; Gardiner, 2005; Patrick & Fletcher, 1998).

The expansion of traditional roles for academic support units and faculty developers in the academy requires a new orientation toward developing human resources and enhancing organizational capacity for change (Chism, 1998; Gilley, Eggland, & Gilley, 2002). Faculty developers are being challenged to extend their knowledge base beyond training and development efforts to incorporate other areas of practice in human resource development. This shift toward a focus on planned, organization-wide development within the academy represents a trend toward maturation of OD practice in higher education (Baron, 2006; Diamond, 2005; Torraco & Hoover, 2005).

Facilitating organizational change is a core component of OD and human resource practice in all types of organizations (Gilley, Eggland, & Gilley, 2002; Swanson & Holton, 2001). Increasingly, individuals responsible for supporting the development of faculty and academic units in the academy are being called on to enhance organizational capacity for effecting positive institutional change (Diamond, 2005; Ruben, 2005; Turnbull & Edwards, 2005). Understanding organizational culture has emerged as an essential component of managing planned change (Bate, 1990; Eckel & Kezar, 2003; Pondy, 1983; Schein, 1996; Tierney, 1990; Trice & Beyer, 1991). Demand for internal consultants with the insight and technical expertise to apprehend and interpret elements of organizational culture will increase in academic institutions, as the internal and external demands on these communities continue to mount (Chesler, 1998). Faculty developers who invest in mastering the cognitive tasks of cultural analysis will be poised to respond to this demand (Diamond, 2005). As Patrick and Fletcher (1998) observe, “since faculty developers come from the ranks of the faculty, they are well positioned to serve a mediating role between the faculty and administration” (p. 164).

Organizational development requires the presence of human resource facilitators at every stage of diagnosis, planning, and implementation (Gardiner, 2005; Rothwell, Sullivan, & McLean, 1995; Smith, 1998). Academic professionals working in OD, including faculty developers, have not always had the opportunity to contribute throughout the full range of the planning cycle (Baron, 2006; Middendorf, 1998). Responding to these shifting institutional demands requires that individuals acquire new skills in organizational assessment, intervention, and change management (Diamond, 2005). Two essential components of this expanded knowledge base for academic professionals working in OD include being familiar with change management and understanding organizational culture.

Change Management

Two types of knowledge inform OD with respect to orchestrating change: 1) content knowledge and 2) process knowledge. Content knowledge of change refers to the substance of a change initiative; it defines what and who is expected to change and to what degree. Process knowledge of change outlines the procedural stages involved in implementing specific change initiatives. Process models describe the steps in planning and implementing change and identify the factors that must be managed throughout implementation (Burke, 2002).

Content Theories of Organizational Change

Content theories of change concern two dimensions of human performance affected by organizational change: behavior and cognition. Behavioral change addresses specific human resource outcomes targeted by an OD intervention. Cognitive change involves the thought processes, attitudes, beliefs, and tacit unconscious mechanisms that mediate behavioral change.

Behavioral Change. Behavioral change is implicit in any change initiative. However, the challenges of specifying and measuring the behavioral outcomes of organizational change have plagued OD researchers and practitioners alike. Determining exactly who, what, and how much change will occur is complicated by the recognition that organizations function as loosely coupled systems, making it difficult to specify the impact of change in one part of the organization on other dimensions (Birnbaum, 1988). The consequences of loose coupling are manifest at both the individual and organizational levels (Weick, 1969). At the individual level, the consequences of loose coupling are evident in the lack of correspondence between learning and performance outcomes (Fenwick, 2006), as well as in the disconnect between attitudes and behavioral change (Gladwell, 2005). At the organizational level, the challenges of identifying and overcoming barriers to transfer of training in organizations is continuing evidence of the difficulty of linking planned change interventions to behavioral change (Bunch, 2007; Hatala & Fleming, 2007).

In an attempt to develop more precise methods of assessing the behavioral impact of organizational change, Golembiewski, Billingsley, and Yeager (1976) conceptualized three types of change, termed alpha, beta, and gamma change. Although Golembiewski’s theory is generally understood as a designation of the degree of behavioral change resulting from a change intervention, it is more accurately described as a theory of measurement respecting the behavioral outcomes of OD. This perspective reflects the fact that change interventions not only modify behavior but simultaneously alter the ways in which behavior is perceived.

Alpha change represents incremental change that can be measured using existing tools of subjective assessment. Beta change is accompanied by the extension of the subjective instruments of assessment that members of an organization use to monitor and evaluate their own and others’ behavior. Gamma change occurs when the behavioral change effected is so great that it requires the adoption of new outcome measures of accomplishment. The subjective changes associated with alpha, beta, and gamma change are not required to produce the behavioral change itself but rather occur as a collateral result. Thus, although not technically a measure of the magnitude of behavioral change, Golembiewski’s theory serves as a conceptual framework for specifying the impact of change on how organizational behavior and outcomes are subjectively assessed.

Cognitive Change. In addition to behavioral change, OD interventions are concerned with effecting cognitive change. Cognitive theories of change invoke the notion of “schemata” (Bartunek & Moch, 1987) or “theories-in-use” (Argyris, 1976) as mediating the impact of change. These mental constructs serve to focus attention, interpret experience, and assign meaning to events. In the context of organizational change, schemata “affect how change agents understand and engage in planned change” (Bartunek & Moch, 1987).

Argyris (1976, 1982) conceptualized cognitive change in organizations as occurring within a system of single- or double-loop learning (Argyris, 1982). Single-loop learning occurs whenever individuals adapt to change without altering their cognitive frameworks. Double-loop learning occurs when organizational problems are approached in a way that allows decision makers to achieve new levels of insight to inform thinking, reasoning, and decision making (Argyris, 1976, 1982). Double-loop learning requires suspending familiar theories-in-use that tacitly govern behavior, in favor of a conscious exploration of the typically unexamined assumptions underlying one’s own and others’ actions (Argyris, 1976). Because double-loop learning requires relinquishing existing cognitive frames that “represent a source of confidence that one has in functioning effectively in one’s world” (Argyris, 1976, p. 370), it involves increased risk and requires leaders who exhibit reduced defensiveness and greater willingness to share power. In this regard, effecting double-loop learning in organizations depends on individuals who have themselves achieved higher levels of cognitive development (Kegan, 1982, 1994).

Bartunek and Moch’s (1987) orders-of-change theory adds another dimension to the cognitive model of change. The degree of cognitive change required by an organizational intervention is conceptualized in this model as first-order, second-order, and third-order change. These orders capture both the magnitude and character of the cognitive modifications required of individuals affected by a change initiative. First- and second-order changes are roughly similar to Argyris’s single- and double-loop learning but described from the perspective of the OD practitioner. Thus, first-order change involves “tacit reinforcement of present understandings,” whereas second-order change effects “the conscious modification of present schemata in a particular direction” (Bartunek & Moch, 1987, p. 486). Third-order change requires “the training of organizational members to be aware of their present schemata and thereby more able to change those schemata as they see fit” (Bartunek & Moch, 1987, p. 486). In each case, the order of magnitude is determined by the nature of the change initiative.

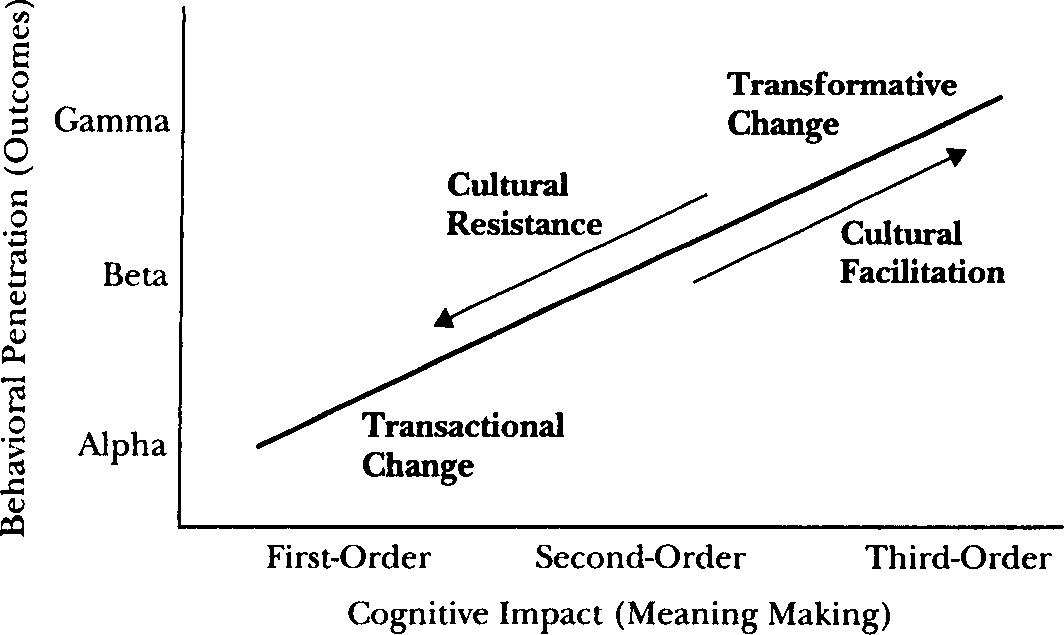

Integration of Behavioral and Cognitive Change. Behavioral and cognitive aspects of human experience underlying the implementation of change have heretofore been conceptualized as independent dimensions of organizational change. Figure 3.1 offers a theoretical framework for illustrating the combined impact of change initiatives on behavioral and cognitive aspects of organizational life. The degree of transformative change is determined by plotting behavioral change (alpha, beta, and gamma change) against cognitive change (first-, second-, and third-order change) on a two-dimensional graph. The former represents the extent of behavioral penetration affected by the change initiative, whereas the latter characterizes the magnitude of cognitive impact required to effect the change. The slope of the line connecting the degree of change on each of these dimensions represents the magnitude of change involved. Every change initiative can be characterized by its placement along this penetration-impact gradient.

Figure 3.1. Integration of Behavioral and Cognitive Theories of Change Illustrating the Impact of Organizational Culture

Figure 3.1. Integration of Behavioral and Cognitive Theories of Change Illustrating the Impact of Organizational CultureSome OD initiatives require limited cognitive change but significant behavioral change, while others require little change of behavior but dramatically new ways of thinking. Initiatives that require minimal modification of behavior and cognitive schemata are characterized as continuous or transactional. The greater the behavioral and cognitive change required, the more transformative (discontinuous) the change initiative (cf. Burke, 2002; Eckel & Kezar, 2003). Understanding the interplay of the behavioral and cognitive demands required to implement a change initiative affords leaders a means of assessing the magnitude of change required to implement strategic objectives. OD practitioners can use these theoretical frameworks to help members of an organization anticipate the impact of strategic organizational objectives and plan effective intervention strategies.

Impact of Organizational Culture on Change. The integrated theoretical content model of change proposed here provides a means of conceptualizing the impact of organizational culture on efforts to implement specific change initiatives. Cultural elements in organizations mediate the implementation of change in a way that either facilitates or inhibits the institutionalization of change, altering the slope and magnitude of the change trajectory (see Figure 3.1). The influence of organizational culture on the content of change can thus be conceptualized as either facilitating or creating resistance to change along the penetration-impact gradient. Understanding the tacit processes of sense making that underlie organizational culture can afford change agents insight into the factors influencing the successful behavioral and cognitive modifications necessary to implement strategic initiatives.

To illustrate the orders-of-change magnitude and the impact of organizational culture, consider the behavioral and cognitive implications of two initiatives currently being implemented at many institutions of higher education: 1) integrating instructional technologies and 2) introducing interdisciplinary curricular reform. The former certainly requires the acquisition of new technical skill, as well as adoption of alternative conceptual approaches to curricular design, requiring both behavioral and cognitive change. But although mastery of these techniques may lead to the adoption of new instructional strategies, it does not necessarily require a redefinition of disciplinary content or instructional goals, or the adoption of new outcome measures of success. In terms of change magnitude, these reforms occur closer to the transactional end of the penetration-impact gradient. Integrating interdisciplinary perspectives into the curriculum, on the other hand, requires a far more penetrating level of change, both in terms of redefining behavioral outcomes of learning (penetration) and with respect to the nature of the cognitive frames required to embrace new interdisciplinary perspectives (impact). This represents a far more transformative change that is therefore more vulnerable to the facilitative or resistant dimensions of organizational culture.

Process Models of Organizational Change

Process models of organizational change designate the sequence of events required to effect organizational change. These models reflect differing levels of granularity with respect to the process of effecting organizational change, but each recognizes distinctive stages of change implementation (Burke, 2002; Hurley, 1990; Lueddeke, 1999; Neumann, 1995). A generic process model of organizational change delineates a sequential progression through six stages: 1) assessing readiness for change, 2) creating a vision for change, 3) specifying intervention initiatives, 4) developing implementation strategies, 5) institutionalizing the effect of change, and 6) assessing the impact of change.

Process models of organizational change increasingly incorporate elements of organizational culture and the inherent processes of meaning making that it embodies as one of many component factors affecting change implementation. Some of these models acknowledge the influence of tacit dimensions of organizational life at one or more stages of the change process, without explicitly identifying organizational culture. The influence of these forces is implicit in Lewin’s (1947) classic “unfreeze-change-refreeze” theory of change, as well as in subsequently popularized “vision” models, such as Kotter’s (1996) eight-step strategy for leading change, Senge’s “fifth discipline” (1990), and Kouzes and Posner’s (2002) “leadership challenge.”

Integrated process models of organizational change (Burke & Litwin, 1992; Kanter, Stein, & Jick, 1992; Tichy, 1983), including some specific to institutions of higher education (Baker, 1998; Eckel & Kezar, 2003; Hurley, 1990; Latta, 2006; Lueddeke, 1999; Shults, 2006), have been developed to inform OD practitioners’ understanding of the impact of cultural dimensions on processes of implementing organizational change. These models vary with respect to whether behavior or cognitive change is expected to occur first (Burke, 2002). Other theorists have developed “culturally sensitive” process models that locate organizational culture as the target of change initiatives (Bate, 1990; Bate, Kahn, & Pye, 2000; Wilkins & Dyer, 1988). Still others suggest that cultural considerations may be more important in effecting some types of change than others (Beer & Nohria, 2000; Kezar, 2001).

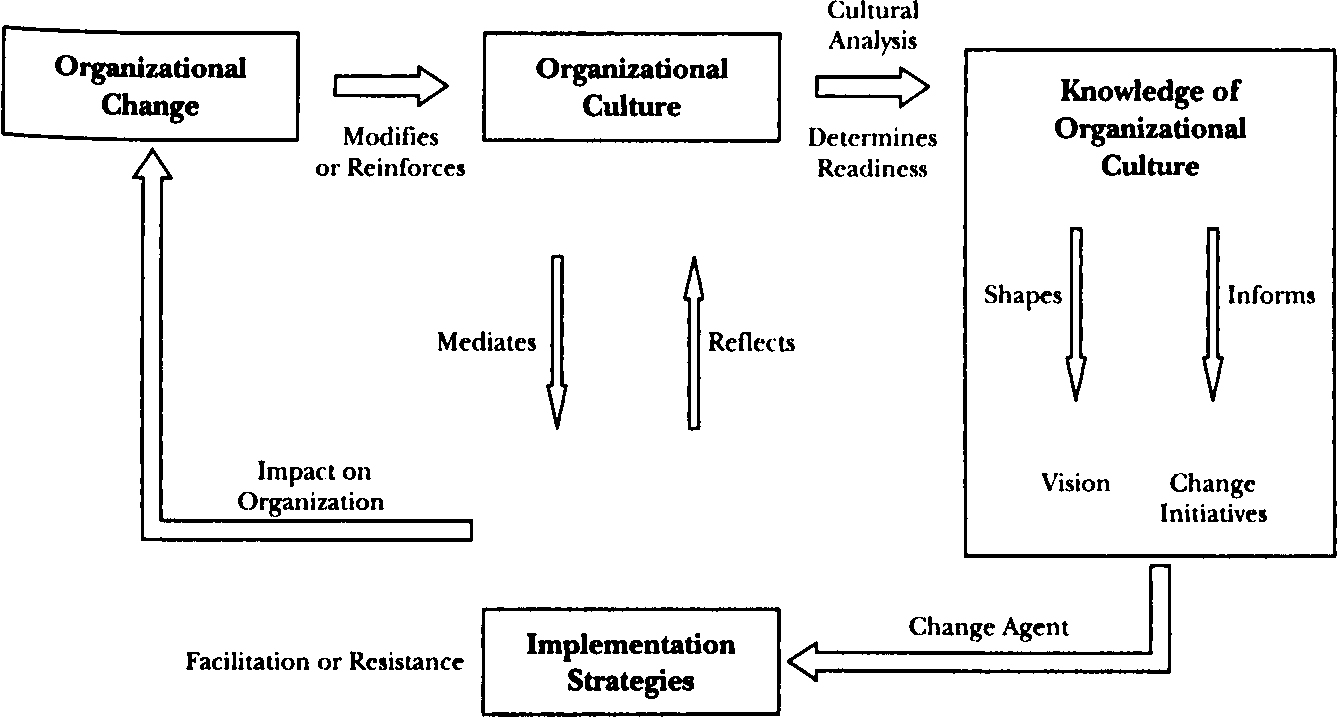

Organizational culture has consistently emerged as a crucial ingredient in the success of efforts to implement institutional change (Curry, 1992; Fullan & Miles, 1992; Heracleous, 2001; Johnson, 1987; Pascale, Milleman, & Gioja, 1997). Latta (2006) has recently developed a process model of organizational change in cultural context (OC3 Model) that takes into consideration the mediating influence of organizational culture at every stage of change implementation (see Figure 3.2). This model applies whether culture is the target of change or not. A central assumption of this model is that cultural knowledge is a prerequisite for leading effective change. Although space does not permit full elaboration of the OC3 Model (see Latta, 2006), it is reproduced here to illustrate visually the integral link between organizational culture and change.

Figure 3.2. OC3 Model of Organizational Change in Cultural Context: The Critical Role of Understanding Organizational cultureSource: Adapted from Latta (2006).

Figure 3.2. OC3 Model of Organizational Change in Cultural Context: The Critical Role of Understanding Organizational cultureSource: Adapted from Latta (2006).Understanding organizational culture emerges as a crucial component of effecting organizational change from the perspective of both content and process models of change. These models predict that creating profiles of organizational culture and documenting variations among subcultures within the academy constitute critical contributions to the success of efforts to effect lasting institutional change. Because cultural knowledge is largely tacit, it often requires the mediation of an outside facilitator to elicit (Heracleous, 2001; Schein, 1999, 2004). Internal facilitators, familiar with the techniques of cultural analysis, can also be effective in conducting a cultural self-assessment or audit (Austin, 1990; Fetterman, 1990; Kuh & Whitt, 1988).

Faculty working in academic support units are well poised to respond to the need for internal facilitators to help academic units understand the cultural norms that mediate the implementation of change (Diamond, 2005). Creating integrated cultural profiles can also provide academic administrators insight into the meaning making norms embedded in the culture of the institutions they lead (Birnbaum, 1989; Neumann & Bensimon, 1990). By revealing the underlying thought processes, decision making, and behavioral norms of an institution, cultural analysis can provide academic leaders the knowledge they need to serve as effective agents of change (Baird, 1990; Bensimon, 1990; Neumann, 1995).

The Nature and Functions of Organizational Culture

Culture is fundamentally about meaning making. Common to all definitions of culture in organizations is the assertion that culture is a socially constructed reality rooted in cognitive processes of meaning making (Alvesson, 2002; Heracleous, 2001; Martin, 2002; Neumann, 1995; Schultz, 1995). Scholars in many disciplines operate from the epistemological position that human beings are innately disposed to impose meaning on their experiences (Schultz, 1995). Bolman and Deal (1991) assert that the human need for meaning is more basic than any others identified in Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs. Culture embodies the systems of shared meaning embedded in organizations (Peterson & Smith, 2000). These systems of meaning are jointly created and collectively preserved by individuals working together toward common goals (Schulz, 1995).

The processes of meaning making that culture sustains afford regularity and familiarity to everyday life. However, cultural knowledge differs from many other subjective realities that define human experience in being largely tacit (Trice & Beyer, 1991). Thus, unlike emotion, attitudes, and reason, which constitute the primary substance of conscious awareness, cultural knowledge operates primarily at a subconscious level (Rousseau, 1990). Although it informs decision making and actions, cultural knowledge does not routinely constitute the focus of introspective rumination. Consequently, most people find it difficult to articulate the cultural norms, values, and basic beliefs that inform their own actions, beyond those embodied in institutional mission statements or declarations of organizational values.

Challenges of Studying Organizational Culture

The challenges of studying organizational culture derive largely from its tacit character. Because of its implicit nature, organizational culture is transmitted indirectly through inductive means (Schein, 2004). The behavior of new members of any culture-sharing group is shaped through successive approximations of assimilation—a process made easier when existing norms are consistent with prior experience. This inductive method of transmission renders cultural knowledge difficult to articulate, requiring elaborate techniques to elicit. As Schein (1999) notes,

What really drives the culture—its essence—is the learned, shared, tacit assumptions on which people base their daily behavior. It results in what is popularly thought of as “the way we do things around here,” but even the employees in the organization cannot without help reconstruct the assumptions on which daily behavior rests. (p. 24)

This latter assumption that most individuals require assistance articulating cultural knowledge has given rise to a host of techniques for eliciting the cultural tenets that govern meaning making and behavior in organizations.

Two intellectual skills are required for conducting cultural analysis in organizations: 1) the ability to discern and document elements of culture extant within the academic community and 2) familiarity with the conceptual frameworks for deciphering the cultural forms that emerge from such an analysis and interpreting the meaning systems embedded in these cultural forms. The remainder of this chapter provides a conceptual guide for mastering these skills and representing the results of cultural analysis in a usable format.

Approaches to Cultural Analysis in the Academy

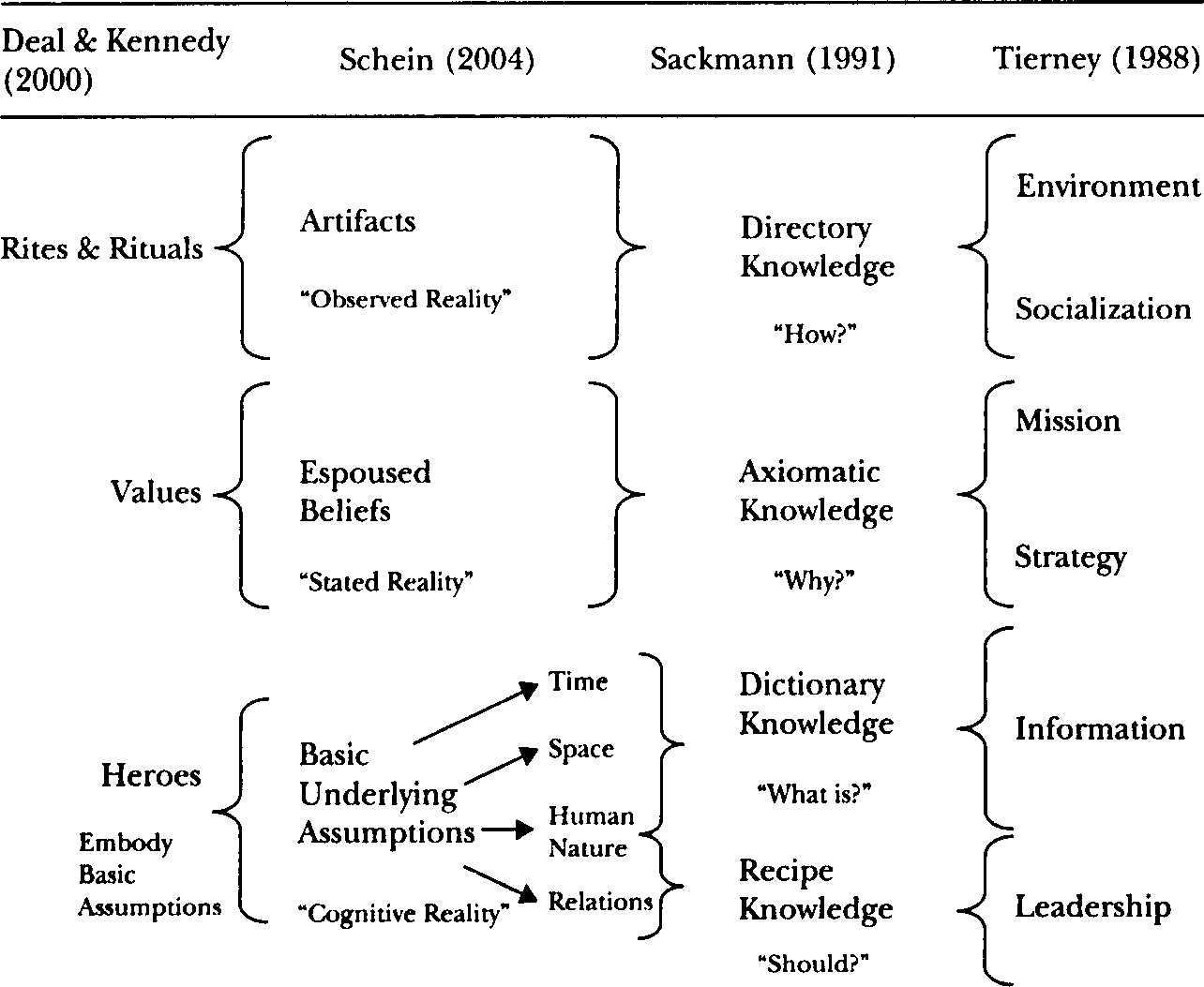

Cultural analysis is not a uniform set of procedures, perspectives, and practices but a diverse assortment of epistemological strategies or “ways of knowing” that can be employed by OD practitioners for understanding patterns of sense making in organizations. Understanding the conceptual variations and distinctions inherent in these different approaches to deciphering organizational culture will enable organization developers to select and use appropriate strategies that align with particular institutional purposes and settings. Many of the interrelationships among the various perspectives on organizational culture discussed in this chapter are portrayed graphically in Figure 3.3.

Elements of Organizational Culture

The study of organizational culture focuses on “the beliefs, values and meanings used by members of an organization to grasp how the organization’s uniqueness originates, evolves, and operates” (Schultz, 1995, p. 5). Driskell and Brenton (2005) catalog many elements of culture that constitute the object of cultural analysis in organizations. Trice and Beyer (1993) make a distinction between ideological and concrete elements of culture. The former refers to beliefs and values, whereas the latter encompasses an extensive array of artifacts, which they call cultural forms. Deal and Kennedy (2000) incorporate this dichotomy into their taxonomy of cultural elements, focusing on rites and rituals (concrete elements) and values (ideological elements), while adding an emphasis on the role of heroes in manifesting concrete human embodiments of ideological dimensions of organizational culture.

Schein (2004) consolidated the basic elements of organizational culture identified by others, classifying them into three broad categories and arranging them into a hierarchical model. The three broad categories of cultural elements in Schein’s hierarchy are 1) artifacts, 2) espoused belief and values, and 3) basic underlying assumptions. These categories correspond to manifestations of observed reality (artifacts), stated reality (espoused beliefs), and cognitive reality (basic assumptions), organized according to increasing levels of conceptual abstraction (see Figure 3.3).

Schein (2004) asserts that organizational culture emerges from the institutional struggle to survive against internal and external threats. He maintains that the core of culture reveals itself through these struggles, in the form of basic assumptions relating to five ontological dimensions of human existence: 1) truth, 2) time, 3) space, 4) human nature, and 5) relationships. All other cultural aspects of organization life are postulated to devolve from shared beliefs concerning these elemental dimensions. Other theorists echo this view that underlying the primary functions of problem solving and sense making in organizations is the fundamental role of culture in defining the nature of reality (Alvesson, 2002; Sackmann, 1991).

Cultural Elements in Higher Education Institutions

Tierney (1988) developed a taxonomy of cultural elements specific to the context of higher education. This framework, “delineating and describing key dimensions of culture,” sought to outline “essential concepts to be studied at a college or university” in conducting ethnographic research (Tierney, 1988, p. 8). Six dimensions of organizational culture emerged as essential to such an analysis: 1) environment, 2) mission, 3) socialization, 4) information, 5) strategy, and 6) leadership. The elements of this framework serve equally well as a guide for OD professionals creating profiles of organizational culture in institutions of higher education.

The six dimensions in Tierney’s (1988) taxonomy can be mapped onto Schein’s (2004) hierarchical model of organizational culture (see Figure 3.3). Institutional norms relating to environment and socialization represent specific types of artifacts. Institutional mission and strategy embody the espoused values and beliefs of an organization. Questions relating to “what constitutes information, who has it, and how [it is] disseminated” (Tierney, 1988, p. 8) correspond to basic assumptions about the nature of reality in Schein’s hierarchy. Finally, Tierney’s attention to institutional leadership, particularly the use of symbolic communication to garner support for aspirational goals, suggests a link to Schein’s basic assumptions about truth.

Cultural Typologies in Higher Education Institutions

Cultural analysis involves more than merely enumerating the cultural elements that characterize a particular organization. Rather, it is the interrelationships among these elements and how they function as an integrative whole that determines the specific cultural forms exhibited (Alvesson, 2002). Cultural forms emerge when elements of culture are interpreted in light of the rules of sense making employed by members of a culture-sharing group (Geertz, 1973; Lévi-Strauss, 1969). Interpreting cultural elements requires an understanding of these rules and how they are used by members of an organization to create meaning from experience in the context of organizational life (Neumann, 1995; Peterson & Spencer, 1990).

Two approaches characterize the application of cultural analysis in organizations: 1) normative and 2) idiomatic. The normative approach seeks to identify cultural forms that span multiple organizations, providing a basis for comparative analysis. Idiomatic cultural forms result in distinct cultural profiles and reflect emergent constructs that operate uniquely in the context of a single institution. The application of cultural analysis techniques to academic organizations has fostered the derivation of a number of useful typologies of normative cultural forms, called archetypes. Distinctions among these normative typologies are detailed in Table 3.1 and will be reviewed before turning to a discussion of the processes involved in deriving idiomatic cultural profiles.

| Kuh & Whitt, 1988 “Cultural Tapestry” | Birnbaum, 1988 “Cognitive Frames” | Bergquist, 1992 “Six Cultures” |

|---|---|---|

| Faculty | Collegial | Collegiate |

| Basic assumption: rational | Basic assumption: egalitarianism | Basic assumption: rationality |

| Values: academic freedom, truth seeking, autonomy | Values: consensus, shared power, common aspirations, consultation | Values: autonomy, shared governance, collaboration |

| Characteristics: intellectual scrutiny, collegiality, shared governance | Metaphor: “community of scholars” | Purpose: conduct research and scholarship, encourage student learning and development |

| Purpose: disseminate knowledge, criticize society, foster life of the mind | Characteristics: self-governance, collegiality, institutional loyalty, reciprocity, loose coupling | Artifacts/ceremonials: grants, publication, commencement |

| Subcultures: disciplinary affiliations | Administrative presence: minimal hierarchy, informality, deliberation | |

| Leadership: leader is “first among equals”; expert and referent power | ||

| Administration | Bureaucratic | Managerial |

| Basic assumption: separatism | Basic assumption: efficiency | Basic assumption: efficiency |

| Values: leadership, balance priorities | Values: certainty, predictability, compliance | Values: fiscal responsibility, effective supervision, planning, competence |

| Characteristics: multiple constituencies, stewardship | Metaphor: “rational organization” | Purpose: inculcate in undergraduates the knowledge and skills for vocational success |

| Purpose: manage resources and personnel | Characteristics: division of labor, codification of rules, vertical administrative loops, tight coupling | Artifacts/ ceremonials: enrollments, revenue generation, bureaucracy |

| Subcultures: task-related academic, student affairs, fiscal, campus facilities | Administrative presence: hierarchy determines information access, objectives, rewards merit | |

| Leadership: based on rationality, competence, expertise; legitimate power, delegation of authority | ||

| Developmental | ||

| Basic assumptions: growth/ maturation | ||

| Values: student-centered learning, demographic systems of planning | ||

| Purpose: maximize cognitive, behavioral, and affective potential | ||

| Artifacts/ceremonials: institutional research, faculty/ program development | ||

| Students | Political | Advocacy |

| Basic assumption: peer influence | Basic assumption: negotiation | Basic assumption: egalitarianism |

| Values: hedonism, informality, flexibility, autonomy, support | Values: social exchange, mutual dependence, decentralized power | Values: confrontation, fair bargaining, mediation, academic capital |

| Characteristics: informal, fluid, social experimentation | Metaphor: “shifting kaleidoscope” | Purpose: to progressively substitute liberating social attitudes and structures for repressive ones, service learning |

| Purpose: promote social networking, affiliation, coping, information sharing, personal validation | Characteristics: interest groups and coalitions; emerging issues | Artifacts/ceremonials: policies, benefits, collective bargaining agreements, community involvement |

| Subcultures: affiliations influenced by personal interests, ideology, living arrangements, recreation | Administrative presence: loosely coupled coalitions and negotiation | |

| Leadership: informal, intuitive | ||

| Anarchical | Virtual | |

| Basic assumption: irrationality | Basic assumption: open systems | |

| Values: fluidity, self-interested participation, persistence | Values: responsiveness in the face of fragmentation and ambiguity | |

| Metaphor: “organized anarchy” | Purpose: foster global education, online learning, knowledge dissemination | |

| Characteristics: lack of control or coordination; vague goals, unclear technology, fluid participation | ||

| Administrative presence: individual autonomy, minimal oversight; open participation; loose coupling | ||

| Leadership: bounded rationality; decision making in uncertainty; symbolic over instrumental action | Artifacts/ ceremonials: networks, technological resources, Partnerships | |

| Tangible | ||

| Basic assumption: parochialism | ||

| Values: tradition, standards, ancestry, reputation, identity, work itself | ||

| Purpose: institutional growth, resident education, | ||

| preservation of roots | ||

| Artifacts/ ceremonials: physical campus attributes, historical memorabilia, commencement exercises |

Normative Cultural Forms in Institutions of Higher Education

Kuh and Whitt (1988) focused on the distinct cultural forms represented by three subpopulations within the academy: 1) faculty, 2) students, and 3) administrators. The faculty culture “provides a general identity for all faculty” (p. 76) but is characterized by fragmentation among disciplinary subcultures. The student culture is a heterogeneous cultural form that affords students a “means to cope with the difficulties of college life by providing students with social support and guidelines to live by” (p. 89). It can serve as either a conservative influence or force for change within the institution. Administrative subculture is characterized by a separatism from both faculty and student cultures in the academy, which tends to foster cultural norms not reflective of the values held by the majority of those affected by leadership decisions.

Birnbaum (1988) conceptualized four cultural forms he considered exemplary of the range of institutional types extant within the higher education community: the 1) collegiate, 2) bureaucratic, 3) political, and 4) anarchical cultures. He then proposed a fifth, emerging culture—the cybernetic culture—which he portrayed as an “ideal” type (see Table 3.1). Birnbaum asserted that these cultural archetypes rarely exist in pure form in the academy but that this “purposeful simplification” affords clarity to the salient aspects of each, while highlighting “the essential limitation faced by any administrator or researcher who takes a single frame approach to understanding higher education” (Birnbaum, 1988, p. 84).

Bergquist’s (1992) analysis, which initially yielded four cultures of the academy, has recently been revised to account for the emergence of two additional cultural archetypes (Bergquist, 2006). The six currently extant cultural forms identified by Bergquist (1992, 2006) are the 1) collegiate, 2) managerial, 3) developmental, 4) advocacy (formerly negotiating), 5) virtual, and 6) tangible forms (see Table 3.1). Each of these cultural forms is held to exist to some degree within every academic institution, functioning to sustain a particular set of institutional assumptions relating to identity and mission. Bergquist (2006) has recently developed a diagnostic instrument for detecting the presence of the six cultural forms identified in his research, thus providing a new tool for analysts wishing to use a normative, descriptive approach to cultural analysis.

Considerable overlap exists among all three of these typologies of academic culture, affording convergent validity to these normative cultural forms. Both Birnbaum (1988) and Bergquist (1992) produced extensive narrative descriptions of the cultural forms identified through their research and explored the implications of each for organizational development, change, and leadership in institutions of higher education. Kuh and Whitt (1988) conclude that organizational culture is integral to institutional history, integrity, decision making, and leadership. Although space limitations preclude a comprehensive treatment of these separate cultural forms, the essence of each is summarized in Table 3.1.

Based on their findings, these normative cultural theorists all challenged the assumption of cultural uniformity, asserting that separate cultural forms coexist interdependently and vie for dominance within the academy. Their work is significant in that it draws attention to the existence of distinct subcultures within the academy. Organizational subcultures emerge in relation to structural boundaries (departmental, college affiliations), role identification (administrators, faculty, students), and disciplinary perspectives (humanities, sciences, social sciences, technology), as well as intangible dimensions (philosophical, ideological, political). Describing the interactions and power relations among subcultures in organizations is an essential component of conducting a cultural analysis (Howard-Grenville, 2006; Kuh & Whitt, 1988; Sackmann, 1997; Trice & Beyer, 1993).

The frameworks that have emerged from normative studies of organizational culture have been employed by researchers in higher education (Kezar & Eckel, 2002; Smart & St.John, 1996). Most recently, Kezar and Eckel (2002) used Bergquist’s (1992) cultural archetypes, in conjunction with Tierney’s (1988) elemental framework, to differentiate the cultural profiles derived from their ethnographic study of institutional change strategies at six higher education institutions. They discussed the advantages and disadvantages of these two approaches as tools for organizational development:

When using both frameworks together, they provide a more powerful lens than when using only one in helping to interpret and understand culture. The archetypes provide a ready framework for institutions unfamiliar with cultural analysis; the framework establishes patterns for them to identify. The Tierney lens provides a sophisticated tool for understanding the complexities of unique institutions. Although Tierney’s framework is an important framework, it may be more difficult for practitioners to use readily. (Kezar & Eckel, 2002, p. 440)

This work draws attention to the utility of employing normative cultural frameworks as a means of understanding and interpreting the attitudes, behavior, and assumptions that characterize many academic communities without requiring extensive cultural analysis.

In the context of facilitating OD, awareness of pervasive cultural norms within the academy yields insight into the complexities of implementing organizational change. Normative approaches to cultural analysis provide an effective means of understanding the competing values and underlying assumptions that create sources of facilitation or resistance to change initiatives. Normative approaches to cultural analysis enable facilitators of OD to describe and test certain assumptions about values and expectations as a means of helping faculty and administrators understand differences of perspective and negotiate toward common ground.

Idiomatic Approaches to Cultural Analysis

The normative approach to cultural analysis has yielded many insights and provided a useful platform for understanding the commonalities of organizational culture that characterize institutions of higher education. Despite these common elements, culture in organizations is ultimately unique. Normative approaches to cultural analysis often obscure the idiosyncrasies that give institutions their distinctive character. Researchers adopting an idiomatic approach to cultural analysis strive to overcome this limitation by constructing cultural profiles that uniquely describe particular academic communities.

In Schein’s (2004) view, culture can best be apprehended by starting with the most visible and least abstract elements (artifacts) and progressing to successively more conceptual and abstract dimensions (basic assumptions). He stressed, however, that the interpretation of cultural elements must progress in an inverse manner, from the most abstract underlying assumptions to the behavioral norms and visible artifacts: “In other words, if I understand the pattern of shared basic assumptions of a group, I can decipher its espoused values and its behavioral rituals. But the reverse does not work. One cannot infer the assumptions unless one has done extensive ethnographic research” (Schein, 1991, p. 252).

The power of ethnographic analysis lies in its potential to yield a unique cultural profile of an organization, reflecting the self-understanding and implicit rules governing behavior, decision making, and meaning making in organizations (Heracleous, 2001; Howard-Grenville, 2006; Neumann, 1995; Neumann & Bensimon, 1990). Such analysis can result in the construction of a cultural profile that more directly mirrors the language and everyday behavior of organization members (Alvesson, 2002; Schultz, 1995).

Ethnographic Analysis. Conducting an ethnographic analysis of organizational culture requires documenting and interpreting organizational behavior from both an emic (insider) and etic (outsider) perspective (Fetterman, 1990, 1998). Documenting these elements requires conducting unobtrusive observation and systematic interviews with key informants (Latta, 2006). These ethnographic interviews involve more than reflective listening; they are actively investigative. Informants must be willing to engage in penetrating dialogue intended to surface the cognitive, motivational, and affective tenets that constitute the bases for individuals’ behavior, attitudes, and decisions, as well as the interpretations and meaning they attribute to organizational experiences and events.

The ethnographic approach to apprehending the tenets of organizational culture is distinguished by three characteristics: 1) researcher reflexivity, 2) reactions of principle members, and 3) iterative hypothesis testing (Heracleous, 2001). The researcher records observations but also keeps track of his or her own reactions. The interviewer continuously formulates and tests hypotheses about the nature of cultural tenets at work in the community by asking questions informed by observations, experiences, and interactions with others. Methodological guides are available to assist in mastering the techniques of conducting ethnographic investigations using observations and interviews with key informants (Alasuutari, 1995; Creswell, 2008; Fetterman, 1990, 1998; Rhoads & Tierney, 1990; Wolcott, 1999).

Constructing Idiomatic Cultural Profiles. Transforming ethnographic observations into idiomatic cultural profiles is an interpretive process (Alasuutari, 1995). Three analytical perspectives inform this approach to cultural analysis: Sackmann’s (1991) cultural knowledge taxonomy, Martin’s (1992, 2002) three-perspective analysis, and Latta’s (2006) cultural profile-matrix approach. These approaches share a dependence on ethnographic analysis but offer alternative means of integrating and rendering cultural insights visible. The conceptual distinctions among these approaches are outlined in Table 3.2.

Sackmann’s (1991) cultural knowledge taxonomy was derived using a “quasi-ethnographic” approach to cultural analysis. The taxonomy consists of a four-dimensional matrix for representing the results of ethnographic analysis in organizations, focusing on four types of information transmitted by culture: 1) dictionary, 2) directory, 3) axiomatic, and 4) recipe knowledge. Dictionary knowledge concerns the nature of reality and answers the question, What is? It relates to organizational purpose, membership, strategy, and design. Directory knowledge relates to cultural norms governing interpersonal relations, learning, adaptation, and change. Axiomatic knowledge reveals insights about underlying organizational purpose and encompasses aspects of culture that correspond to the question, Why? The fourth type of cultural knowledge—recipe knowledge—represents the presence or absence of aspirational or subversive elements in organizational culture, existing in the form of expectations concerning how things “should” be (see Table 3.2). Sackmann (1991) asserts that high-performing organizations with internally consistent cultures will be characterized by smaller amounts of recipe knowledge than those experiencing cultural discord.

| Sackmann, 1991 “Knowledge Taxonomy” | Martin, 2002 “Multiple Perspectives” | Latta, 2006 “Cultural Profile-Matrix” |

|---|---|---|

| Dictionary Knowledge | Integration Perspective | Dominant Cultural Profile |

| What is? | ||

| Purpose | Shared aspects of culture | Unique idiomatic cultural profile |

| Members | Organization-wide consensus | Emergent tenets of organizational culture |

| Design | Internal consistency | Pervasive elements of culture that sustain basic cultural tenets |

| Directory Knowledge | Differentiation Perspective | Matrix of Subcultural Variations |

| How to? | ||

| Accomplish tasks | Subcultural consensus | Variations from dominant cultural profile |

| Manage relations | Organization-wide variations | Divergence and convergence among subcultures |

| Learn | ||

| R.ecipe Knowledge | Fragmentation Perspective | |

| What should be? | ||

No clear consensus Irresolvable inconsistencies | ||

| Axiomatic Knowledge | ||

| Why? |

Sackmann’s (1991) taxonomy provides a bridge between normative and idiomatic methods of cultural analysis. The types of knowledge delineated by Sackmann’s taxonomy can be mapped onto the elements of Schien’s (2004) basic hierarchical model of cultural forms in organizations (see Figure 3.3): directory knowledge is revealed through cultural artifacts; axiomatic knowledge embodies espoused beliefs and values; dictionary knowledge concerns basic assumptions relating to the nature of time, space, relationships, and human nature. The identification of recipe knowledge separates basic assumptions about truth from other fundamental beliefs, adding a dimension of vision regarding what should be and thus also aligns with the role of leaders and heroes in the taxonomies of Tierney (1988) and Deal and Kennedy (2000). Yet the four categories in Sackmann’s (1991) cultural knowledge taxonomy differ from the categories defined in normative approaches to cultural analysis by focusing on the dimensions of meaning embodied in organizational culture, rather than the cultural forms themselves.

Sackmann’s (1991) work further departs from normative approaches to analyzing culture in organizations by drawing attention to the fact that cultural knowledge encompasses dimensions pertaining to both the current and future desired states of an organization. Although Sackmann’s cultural knowledge taxonomy has not been widely used by researchers or practitioners, it holds promise as a tool for facilitating organizational development in the context of change management. The inclusion of aspirational norms (recipe knowledge) affords added utility to employing this model of organizational culture as a means of identifying performance gaps in the context of planned change (Bate, Kahn, & Pye, 2000; Gilley & Maycunich, 1998; Rothwell, 1996).

Martin’s (2002) three-perspective conceptual model of organizational culture represents a more dramatic departure from normative approaches than Sackmann’s. Martin advanced her multidimensional model of cultural analysis as an alternative to the analytical, descriptive approach to isolating separate cultural forms. Martin (1992) championed the notion that culture does not manifest as separate, objective, reified forms in organizations but instead constitutes a multidimensional, subjective reality that should be analyzed simultaneously from three different perspectives. These perspectives reflect the degree of integration, differentiation, and fragmentation that exists within the fabric of the organization’s culture. The analysis resulting from this multipleperspectives approach emphasizes the notion that elements of uniformity, diversity, and discontinuity coexist within the culture of an organization, which obviates the need to develop cultural typologies to account for differences within the organization’s meaning-making systems.

The three dimensions of meaning emphasized by Martin’s approach highlight different aspects of organizational culture (see Table 3.2). The integration perspective highlights those aspects of culture that pervade the organization, cutting across hierarchy, roles, and organizational units. The differentiation perspective, on the other hand, acknowledges the existence of subcultural variations along certain salient dimensions where integration exists only within formally or informally defined groups within the organization. Finally, the fragmentation perspective focuses on “ambiguity as the essence of organizational culture” (Martin, 1992, p. 12), explicitly acknowledging dimensions of the organizational life where no clear consensus exists.

Using Martin’s approach to cultural analysis, it is possible to document that an academic community may share a pervasive cultural commitment to maintaining a prestigious level of research achievement (integration perspective), yet harbor considerable subcultural variation among academic units with respect to the value placed on teaching excellence (differentiation). At the same time, there may be a complete lack of consensus about the role and value of outreach (fragmentation). Martin’s three-perspective approach to cultural analysis is designed to reveal these qualitatively different dimensions of cultural manifestation. Although Martin’s three-perspective approach has been largely ignored by researchers studying culture in the academy, the cultural perspectives defined by Martin’s work have broad applicability in large, complex organizations such as institutions of higher education.

One limitation of Martin’s approach that may account for its underuse is its failure to yield an integrative cultural profile that represents both cultural integration (uniformity) and differentiation (subcultures) along comparable cultural dimensions. The problem of how to treat subcultures in organizations pervades the literature of cultural analysis (Hatch, 1997; Howard-Grenville, 2006; Kuh & Whitt, 1988; Sackmann, 1997) and deserves special attention by those facilitating cultural analysis in the context of organizational change (Bergquist, 1992; Latta, 2006; Sackmann, 1997). Some have explored the presence of subcultures as a potential source of institutional weakness (Deal & Kennedy, 2000; Tierney, 1988; Toma, Dubrow, & Hartley, 2005). Others, however, “caution against building a unified institution that is dominated by one culture . . . and fails to honor the legitimate claims and considerable benefits provided by” other cultural forms (Bergquist, 2006, p. 7).

The typical approach to addressing internal cultural variations results in the creation of separate subcultural profiles for each extant group within the organization (Bergquist, 1992, 2006; Birnbaum, 1988; Kuh & Whitt, 1988; Martin, 1992; Neumann & Bensimon, 1990; Smart & St. John, 1996). Yet this approach makes it difficult for researchers and institutional leaders to understand subtle variations in sense making that occur between seemingly comparable groups across the institution (that is, departments and colleges or faculty with different disciplinary affiliations). Thus, two academic departments, each exemplars of the collegiate cultural form, may differ significantly in the particulars of how that culture manifests. Employing normative analysis in this instance has the drawback of obscuring the distinctive aspects of institutional culture necessary for understanding nuances that exist within the organization as a whole. Martin’s (2002) three-perspective approach, on the other hand, treats cultural integration as separate from subcultural variations. Latta (2006) developed an integrated approach to idiomatic cultural analysis that overcomes both these limitations.

Latta’s (2006) cultural profile-matrix approach involves first documenting the hierarchical relations among elements of organizational culture as a whole, then delineating variations in the degree to which each dimension of the overall culture is manifest within organizational subcultures (see Table 3.2). The first step results in a profile of the dominant organizational culture, detailing the relationship among basic beliefs (assumptions) and the underlying cultural elements (artifacts, values, behavior norms, and so on) that sustain these beliefs (see Table 3.3). The second step involves creating a matrix detailing the degree to which each subcultural group within the institution conforms or diverges from the tenets of this dominant cultural profile (see Table 3.4).

| Dominant Cultural Tenets | Cultural Elements That Sustain Each Tenet |

|---|---|

| Pervasive paternalism | Dominance of business officers Respect for administrative hierarchy Advisory role of faculty senate |

| Culture of prestige | Aversion to pubic debate of issues Sense of industry and competition Reciprocal institutional loyalty Intolerance for nonconformity |

| Land-grant identity | Balance of teaching and research Dominance of applied disciplines |

| Decentralization of power | Unit level self-determinism College subcultures Differential power among colleges |

The utility of Latta’s (2006) approach is that it permits both the emergence of a unique cultural profile (the goal of idiomatic analysis), while at the same time providing a means of describing subcultures along comparable cultural dimensions (the strength of normative approaches). If the example were extended, the dominant cultural profile would include elements of culture relating to the nature of the organization’s overall commitment to research, teaching, and outreach. Deviation from, or consistency with, these overall cultural commitments would then be documented in a matrix of organizational subcultures. Tables 3.3 and 3.4 provide examples of the types of cultural representations resulting from Latta’s cultural profile-matrix approach to cultural analysis.

| Cultural Elements | Engineering | Science | Technology | Business | Liberal Arts | Agriculture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prestige | very strong | strong | weak | very strong | moderate | moderate |

| Paternalism | strong | strong | strong | strong | strong | strong |

| Aversion to debate | strong | moderate | strong | strong | weak | strong |

| Industriousness | very strong | strong | weak | very strong | moderate | moderate |

| Teaching/Research | moderate | strong | very strong | moderate | very strong | very strong |

| Land grant | strong | weak | strong | moderate | weak | strong |

| Self-determinism | very strong | strong | strong | very strong | strong | strong |

| Loyalty | strong | strong | strong | strong | strong | strong |

Together, the dominant cultural profile and the matrix of subcultural variations provide a visual representation of the organization’s unique cultural makeup, capturing both the substance and internal dynamics moderating the processes of institutional sense making. These tools of cultural analysis supplement the traditional “thick description” narratives characteristic of ethnographic research (Fetterman, 1998; Geertz, 1973). Although illustrating the application of the cultural profile-matrix approach to cultural analysis is beyond the scope of this chapter, Latta’s (2006) research on institutional change at land grant universities provides numerous examples that demonstrate the utility of this form of cultural analysis for identifying the mediating influence of culture at every stage of a planned change process. The approach has particular value as a tool for identifying the sources of cultural facilitation and resistance to change implementation. Although the utility of this approach to cultural analysis has not yet been demonstrated beyond the academic environment, it is expected to have broad applicability in organizations characterized by distinct subcultural factions.

Conclusion

Change management and cultural analysis have become mainstream practices in organizational development outside the academy (Cummings & Worley, 2000; French & Bell, 1999). Both are essential tools for effective leadership in academic institutions as well (Astin & Astin, 2000; Eckel, Hill, Green, & Mallon, 1999). Understanding content and process models of change affords increased awareness of the importance of considering the impact of organizational culture on the success of change initiatives. Emerging models of organizational change in cultural context draw increased attention to the importance of integrating cultural analysis into the practice of facilitating OD in institutions of higher education (Bate, Kahn, & Pye, 2000; Latta, 2006; Wilkins & Dyer, 1988).

Mastering the craft of interpreting elements of organizational culture has thus become an essential tool for leaders of organizational change, enabling them to maximize their potential to effect positive change that will have lasting results (Curry, 1992). Two alternative approaches to cultural analysis—normative and idiomatic—provide options for individuals called upon to support the implementation of change initiatives. Normative approaches provide the advantage of using preexisting cultural typologies, common to many academic institutions, for anticipating and interpreting reactions to institutional change. Normative cultural typologies benefit from a high degree of face validity, without requiring investment in extensive assessment and analysis.

However, normative cultural analysis lacks specificity and fails to capture unique aspects of institutional culture that may be essential for understanding and implementing change. Idiomatic approaches to cultural analysis require a greater investment in assessment but offer the advantage of capturing unique nuances of organizational culture that may be essential to the success of OD initiatives. Idiomatic cultural analysis provides greater insight into differences among institutional subcultures. Understanding unique aspects of organizational culture can help OD professionals interpret the behavior of individuals and organizational units, permitting them to understand motivations and pinpoint the underlying causes of dysfunction or discontent, while anticipating sources of facilitation or resistance that may arise in advancing strategic initiatives (Latta, 2006).

Using cultural analysis techniques to support institutional change initiatives in the academy represents an effective strategy for furthering the maturation of organizational development in institutions of higher education. Faculty developers and other members of the academy working to facilitate organizational development can capitalize on their roles as internal facilitators to help academic leaders understand the implicit rules that govern behavior and meaning attribution within the larger organizational context (Baron, 2006; Chism, 1998; Hurley, 1990). This review of change theories and recent advances in cultural analysis provides a conceptual overview of the variety of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches available for discerning and representing the essence of culture and change in the academy. Further research on the use of these various techniques will further inform the selection of effective tools for particular situations. Mastering the techniques of cultural analysis and applying them within the context of organizational change will spur the maturation of OD in institutions of higher education (Rousseau, 1990).

References

- Alasuutari, P. (1995). Researching culture: Qualitative method and cultural studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding organizational culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Argyris, C. (1976). Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 363–375.

- Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, learning, and action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Astin, A. W., & Astin, H. S. (2000). Leadership reconsidered: Engaging higher education in social change. Washington, DC: Kellogg Foundation.

- Austin, A. E. (1990). Faculty cultures, faculty values. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 61–73). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Austin, A. E. (1994). Understanding and assessing faculty cultures and climates. In M. K. Kinnick (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 84. Providing useful information for deans and department chairs (pp. 47–63). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Baird, L. L. (1990). Campus climate: Using surveys for policy-making and understanding. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 35–45). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Baker, G. A. (1998). Managing change: A model for community college leaders. Washington, DC: Community College Press.

- Baron, L. (2006). The advantages of a reciprocal relationship between faculty development and organizational development in higher education. In S. Chadwick-Blossey & D. R. Robertson (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 24. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 29–43). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Bartunek, J. M., & Moch, M. K. (1987). First-order, second-order, and third-order change and organization development interventions: A cognitive approach. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 23(4), 483–500.

- Bate, P. (1990). Using the culture concept in an organization development setting. Journal of Applied Behavioral Student, 26(1), 83–106.

- Bate, P., Khan, R., & Pye, A (2000). Towards a culturally sensitive approach to organization structuring: Where organization design meets organization development. Organization Student, 11(2), 197–211.

- Beer, M., & Nohria, N. (2002). Breaking the code of change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Bennis, W. G. (1969). Organization development: Its nature, origins, and prospects. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Bensimon, E. M. (1990). The new president and understanding the campus as a culture. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 75–86). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bergquist, W. (1992). The four cultures of the academy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bergquist, W. (2006). The six cultures of the academy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Birnbaum, R. (1988). How colleges work: The cybernetics of academic organization and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Birnbaum, R. (1989). The implicit leadership theories of college and university presidents. Review of Higher Education, 12(2), 125–136.

- Blackwell, R., & Blackmore, P. (2003). Towards strategic staff development in higher education. London: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1991). Re.framing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bunch, K.J. (2007). Training failure as a consequence of organizational culture. Human Resource Development Review, 6, 142–163.

- Burke, W. W. (2002). Organization change: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Burke, W. W., & Litwin, G. H. (1992). A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of Management, 18(3), 532–545.

- Chesler, M. A. (1998). Planning multicultural audits in higher education. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 17. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 171–201). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Chism, N. V. N. (1998). The role of educational developers in institutional change: From the basement office to the front office. In M. Kaplan (Ed.), To improve the academy: Vol. 17. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organization development (pp. 141–154). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2000). Organization development and change (7th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western College Publishing.

- Curry, B. K. (1992). Instituting enduring innovations: Achieving continuity of change in higher education. (Report No. 7), ASHE-ERIC Higher Education. Washington, DC: George Washington University.

- Deal, T. E., & Kennedy, A. A. (2000). Corporate cultures. New York: Perseus.

- Diamond, R. M. (2002). Faculty, instructional, and organizational development: Options and choices. In K. H. Gillespie (Ed.), A guide to faculty development: Practical advice, examples, and resources (pp. 2–8). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Driskell, G. W., & Brenton, A. L. (2005). Organizational culture in action: A cultural analysis workbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dwyer, P. M. (2005). Leading change: Creating a culture of assessment. In S. Chadwick-Blossey & D. R. Robertson (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 23. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 38–46). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Eckel, P. D., & Kezar, A. (2003). Taking the reins: Institutional transformation in higher education. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Eckel, P. D., Hill, B., Green, M., & Mallon, B. (1999). Reports from the road: Insights on institutional change. On Change, No. 2. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

- Fetterman, D. M. (1990). Ethnographic auditing: A new approach to evaluating management. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 19–34). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Fetterman, D. M. (1998). Ethnography (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Frantz, A. C., Beebe, S. A., Horvath, V. S., Canales, J., & Swee, D. E. (2005). The roles of teaching and learning centers. In S. Chadwick-Blossey & D. R. Robertson (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 23. Resources for faculty, instructional and organizational development (pp. 72–90). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- French, W. L., & Bell, C.H. (1999). Organizational development (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Fullan, M., & Miles, M. (1992, June). Getting reforms first: What works and what doesn’t. Phi Delta Kappan, 745–752.

- Gardiner, L. F. (2005). Transforming the environment for learning: A crisis of quality. In S. Chadwick-Blossey & D.R. Robertson (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 23. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 3–23). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Gayle, D.J., Tewarie, B., & White, A. Q. (2003). Governance in the twenty.first century university: Approaches to effective leadership and strategic management. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Vol. 30, No. 1). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Gilley, J. W., Eggland, S. A., & Gilley, A. M. (2002). Principles of human resource development (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

- Gilley, J. W., & Maycunich, A. (1998). Strategically integrated HRD: Partnering to maximize organizational performance. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: The power of thinking without thinking. New York: Little, Brown.

- Golembiewski, R. T., Billingsley, K. R., & Yeager, S. (1976). Measuring change and persistence in human affairs: Types of change generated by OD designs. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 12, 133–157.

- Hatala, J., & Fleming, P. R. (2007). Making transfer climate visible: Utilizing social network analysis to facilitate the transfer of training. Human Resource Development Review, 6(1), 33–63.

- Hatch, M. J. (1997). Organization theory: Modern, symbolic, and postmodern perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heracleous, L. (2001). An ethnographic study of culture in the context of organizational change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37, 426–446.

- Howard-Grenville, J. A. (2006). Inside the “black box”: How organizational culture and subculture inform interpretations and actions on environmental issues. Organization Environment, 19, 46–73.

- Hurley, J. J. P. (1990). Organizational development in universities. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 5(1), 17–22.

- Johnson, G. (1987). Strategic change and the management process. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities. (2006). Public higher education reform five years after the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities. Washington, DC: National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges.

- Kezar, A. (2001). Understanding and facilitating organizational change in the 21st century: Recent research and conceptualizations. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Vol. 28, No. 4.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kezar, A., & Eckel, P. D. (2002). The effect of institutional culture on change strategies in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 73(4), 435–459.

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). Leadership challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kuh, G. D., & Whitt, E. J. (1988). The invisible tapestry: Culture in American colleges and universities. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Vol. 17, No. 1.) Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Graduate School of Education and Human Development.

- Latta, G. F. (2006). Understanding organizational change in cultural context: Chief academic officers’ acquisition and utilization of cultural knowledge in implementing institutional change. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

- Latta, G. F., & Myers, N. F. (2005). The impact of unexpected leadership changes and budget crisis on change initiatives at a land-grant university. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(3), 351–367.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1969). The elementary structures of kinship. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Lewin, K (1947). Field theory in social science. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Lueddeke, G. R. (1999). Toward a constructivist framework for guiding change and innovation in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 70(3), 235–260.

- Martin, J. (1992). Cultures in organizations: Three perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, J. (2002). Organizational culture: Mapping the terrain. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. In J. M. Shafritz, J. S. Ott, & Y S. Jang (Eds.), Classics of organization theory (pp. 159–173). New York: Wadsworth Press.

- McLean, G. N. (2005). Doing organization development in complex systems: The case at a large U.S. research, land-grant university. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(3), 311–323.

- Middendorf, J. K (1998). A case study in getting faculty to change. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 17. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 203–223). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Neumann, A. (1995). Context, cognition and culture: A case analysis of collegiate leadership and cultural change. American Educational Research Journal, 32(2), 251–279.

- Neumann, A., & Bensimon, E. M. (1990). Constructing the presidency: College presidents’ images of their leadership roles, a comparative study. Journal of Higher Education, 61(6), 678–701.

- Pascale, R., Milleman, M., & Gioja, L. (1997, November/December). Changing the way we change. Harvard Business Review, 75(6), 127–138.

- Patrick, S. K., & Fletcher, J. J. (1998). Faculty developers as change agents: Transforming colleges and universities into learning organizations. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 17. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 155–169). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Peterson, M. F., & Smith, P. B. (2000). Sources of meaning, organizations, and cultures. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. P. M. Wilderon, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of organizational culture and climate (pp. 101–115). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Peterson, M. F., & Spencer, M. G. (1990). Understanding academic culture and climate. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 3–18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Pondy, L. (1983). The role of metaphors and myths in organizations and in the facilitation of change. In L. Pondy, P. Frost, G. Morgan, & T. Dandridge (Eds.), Organizational symbolism (pp. 157–166). Greenwich, London: JAI Press.

- Rhoads, R. A., & Tierney, W. G. (1990). Exploring organizational climates and cultures. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), New directions for institutional research: No. 68. Assessing academic climates and cultures (pp. 87–95). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Rothwell, W. J. (1996). Beyond training and development: State-of-the-art strategies for enhancing human performance. New York: American Management Association.

- Rothwell, W.J., Sullivan, R., & McLean, G. N. (1995). Practicing organizational development: A guide for consultants. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1990). Assessing organizational culture: The case for multiple methods. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 153–192). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ruben, B. D. (2004). Pursuing excellence in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Sackmann, S. A. (1991). Cultural knowledge in organizations: Exploring the collective mind. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Sackmann, S. A. (Ed.). (1997). Cultural complexity: Inherent contrasts and contradictions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Schein, E. H. (1991). What is culture? In P. J. Frost, L. F. Moore, M. R. Louis, C. C. Lundberg, & J. Martin (Eds.), Reframing organizational culture (pp. 243–253). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Schein, E. H. (1996). Culture: The missing concept in organizational studies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 229–240.

- Schein, E. H. (1999). The corporate culture survival guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schulz, M. (1995). On studying organizational cultures: Diagnosis and understanding. New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline. New York: Doubleday.

- Shults, C. (2006, October). Towards organizational culture change in higher education: Introduction of a model. Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Anaheim, CA.

- Smart, J. C., & St. John, E. P. (1996). Organizational culture and effectiveness in higher education: A test of the “culture type” and “strong culture” hypothesis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18(3), 219–241.

- Smith, B. L. (1998). Adopting a strategic approach to managing change in learning and teaching. In M. Kaplan & D. Lieberman (Eds.), To improve the academy: Vol. 18. Resources for faculty, instructional, and organizational development (pp. 225–242). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Swanson, R. A., & Holton, E. F., III. (2001). Foundations of human resource development. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler.

- Tichy, N. M. (1983). Managing strategic change: Technical, political and cultural dynamics. New York: Wiley.