1 Evaluating Teaching: A New Approach to an Old Problem

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The approach to evaluating the quality of teaching described in this chapter starts by developing a Model of Good Teaching. This model is then used to create a set of evaluation procedures based on four key dimensions of teaching: design of learning experiences, quality of teacher/student interactions, extent and quality of student learning, and teacher’s effort to improve over time. The challenges and benefits of using these procedures are discussed.

American higher education badly needs to find a better way to evaluate teaching. Like any organization, colleges and universities need good procedures for knowing how well the people responsible for accomplishing the primary purposes of the organization are succeeding. For the educational portion of their mission, universities need to know how well their faculty members are succeeding in their role as professional educators—that is, in their assigned responsibilities for teaching tuition-paying students.

As with any organizational feedback procedure, this process needs to be done in a way that supports two important organizational needs. The individuals who teach need feedback that both motivates and enables them to know how well they are doing but also to know how to get better—that is, how to engage in continuous professional development. In addition, organizational leaders (chairs, deans, and provosts) need reliable information about who are and who are not performing well in their roles as professional educators. They need to know who are not performing well so they can encourage them to make a stronger effort to improve, and they need to know who are performing well so they can reward them and encourage them to share their performance insights with others.

Current procedures for evaluating teaching in American higher education are failing miserably on both counts. In a survey of 600 liberal arts colleges, Peter Seldin found that almost 90% use student questionnaires (Seldin & Associates, 1999), and many institutions reduce their assessment of the complex task of teaching to data from one or two questions to rank order faculty members as teachers. In an effort to determine how research universities evaluate teaching, Larry Loeher surveyed 62 Association of American Universities. He found that 98% of them used student questionnaires as “the primary method of evaluating teaching,” and that only 77% of the institutions required faculty to evaluate all courses every term (Loeher, 2006).

These practices are clearly not driving any widespread faculty effort to improve teaching. What they are doing is creating widespread cynicism about teaching evaluations. Many faculty view student ratings as popularity contests, and more than one eyebrow has been raised about the recipients of teaching awards when these are based primarily or solely on student evaluations.

What can be done about this situation? What we do not need is another technical fix—that is, a new technique or procedure that is added to student ratings. This will be rejected as simply adding to the work of evaluating teaching without adding any sense of the need and reason for doing it right. Instead, we need to rethink what teaching is and what teachers should be doing to be “good teachers.” Then we need to develop a set of procedures for evaluating teaching based on this Model of Good Teaching.

In the process of developing a Model of Good Teaching, one has to be careful not to focus on specific ways of teaching or specific teaching strategies. There are different specific ways of being “good.” The model should strive to identify the general principles that cut across and transcend different ways of being successful as a teacher. An analogy would be the challenge of identifying success in sports. In basketball, for example, some teams use a fast “run and gun” type offense; others use a slower, more deliberate style of offense. On defense, some teams use a few basic types of defense well while others deliberately mix up their defensive schemes to keep the other team off balance. Whatever the different specifics, teams can be evaluated in terms of how successful their offense and defense are, and in terms of their ultimate success: Do they score more points than they allow their opponents to score? Similarly, in teaching there are some common tasks that can be assessed and we can look for the ultimate measure of success: Does the teacher succeed in promoting high-quality learning in a high percentage of students?

In this chapter, I will lay out a description of the basic tasks involved in teaching and, based on this, propose an enlarged Model of Good Teaching. Although professors have disparate and sometimes conflicting views about teaching, this model has the potential to gain widespread acceptance because it focuses on general teaching practices rather than on specific activities or specific ways of teaching. Then I will describe procedures for evaluating teaching based on this enlarged Model of Good Teaching. Finally, I will present a case study from a university that used procedures very close to what is proposed here. This case illustrates important points about what good evaluation procedures can accomplish and what else is needed for them to fulfill the organizational needs mentioned earlier—that is, promoting faculty efforts to improve their teaching and giving organizational leaders reliable information about institutional success in its educational mission.

What Teaching Is: Four Fundamental Tasks

Most professors, given the lack of pre-service study of college teaching in graduate school, view their responsibilities as teachers in a rather simple-minded way: “My job as a teacher is to know my subject well and communicate my knowledge to students in a reasonably clear and organized manner.” In fact, teaching involves much more than that. After 30 years of being a college teacher, working with college teachers as a faculty developer, and reading the literature on college-level teaching, I have come to view all teaching as involving four fundamental tasks (see Figure 1.1).

This is what is involved in each of these tasks:

Knowledge of subject matter. Whenever we teach, we are trying to help someone learn about something. The “something” is the subject of the teaching and learning, and all good teachers have some advanced level of knowledge about the subject.

Designing learning experiences. Teachers also have to make decisions ahead of time about what the learning experience is going to include and how they want it to unfold. For example: What reading material will be used? What kinds of writing activities will they have students do? Will there be field experiences? Will the teacher use small group activities? How will student learning be assessed? Collectively, these decisions represent the teacher’s design or plan for the learning experience.

These first two tasks happen primarily before the course begins but continue to a lesser degree during the course as well. Once the course is under way, the other two components come into play in a major way:

Interacting with students. Throughout a course, the teacher and the students interact in multiple ways. Lecturing, leading whole class or small group discussions, email exchanges, writing comments on student papers, and meeting with students during office hours—these are all different ways of interacting with students.

Course management. A course is a complex set of events that involves specific activities and materials. One of the responsibilities of the teacher is to keep track of and manage all of the information and materials involved. A teacher needs to know who has enrolled in the course and who has dropped it, who has taken a test and who was absent, who got what grade on their homework and exams, and so forth.

These four tasks are involved in all teaching, whether traditional or innovative, excellent or poor. Everyone—for better or worse—invokes his or her own knowledge of the subject, makes decisions about the learning experience, interacts with students, and manages information and materials.

My belief is that there is a direct relationship between how well a teacher performs these four fundamental tasks and the quality of the students’ learning experience. If the teacher does all four well, students will have a good learning experience. To the degree that the teacher does one or more poorly, the quality of the learning experience declines.

After working closely with college teachers for many years, my observation is that we are not equally well prepared for each of these four tasks:

With but few exceptions, college teachers have a reasonably good knowledge of their subject. Graduate school training as well as most hiring and tenure procedures are focused on determining whether the person has an in-depth knowledge of their particular discipline.

Our knowledge about course design, however, is a different matter. The vast majority of college teachers have not had any formal training in instructional design. This is one of the reasons that poor course design is the underlying problem behind many of our teaching problems (Fink, 2003).

Teachers’ ability to interact with students varies widely. As a faculty developer, I have observed a lot of teachers interact with their students. Our teacher-interaction skills range from very bad to incredibly good.

As for course management, the majority of teachers handle this task adequately. However, I have seen a few teachers who were so disorganized (handouts not ready on time, materials not put together properly) that it negatively affected the quality of the students’ learning experience.

Because these fundamental tasks are involved in all instances of teaching, we will need to incorporate them in some way into our procedures for evaluating teaching. But this variation in preparation and performance will affect which ones we include.

However, before we move to constructing better procedures for evaluating teaching, we need to look at two other important processes involved in good teaching.

An Enlarged Model of Good Teaching

What is it that we would like to see all teachers do, that would in a general sense constitute “good teaching”? The proposition put forth here is that teachers are good if they do each of the following three things:

Perform the fundamental tasks of teaching well.

Teach in a way that leads to high-quality student learning.

Work continuously at getting better over time as a teacher.

The basic idea here is that any teacher, to be a good teacher, needs to pay attention to—that is, gather information about and act on—all three factors. In this section, I will elaborate on the meaning of these three factors. The next section will show how this model offers a powerful framework for laying out a new way of evaluating teaching.

Fundamental Tasks of Teaching

It is worth noting that the creator of one of the more comprehensive approaches to evaluating teaching, Raoul Arreola (2000), also identified four “defining roles” of teaching: content, delivery, design, and management. These are essentially identical to the four fundamental tasks described here and shown earlier in Figure 1.1.

This suggests there may be growing consensus about the central tasks involved in all teaching. To the degree that this is true, we need to include them in some way in our evaluation of teaching.

The Quality of Student Learning

The quality of student learning occurs in three phases. The desired quality of student learning in each phase can be described in the following way:

During the course: Students are engaged. They attend class regularly, they pay attention, they participate in class discussions, they do the work of learning.

At the end of the course: Student engagement has resulted in significant learning that lasts. Some student learning is not significant and doesn’t last. Good learning is significant and does last.

After the course: That which students learn adds value to their lives. It might do this by enhancing their individual lives (e.g., history, literature), preparing them for the world of work, or preparing them to contribute to the many communities of which we are all a part: family, local community, nation state, global interest groups, and so on.

We want all three of these to occur. But if the teacher finds a way to make the second kind of learning happen—significant learning that has been developed up to and by the end of the course—this greatly increases the likelihood of getting the other two to happen: engaging students during the course and generating learning that adds value to their lives after the course is over. How then might we define “significant learning”?

Elsewhere (Fink, 2003) I have offered a Taxonomy of Significant Learning that builds on the well-known taxonomy of Benjamin Bloom and his associates but tries to incorporate newer kinds of learning that recent writers have advocated. In this taxonomy, like in Bloom’s, there are six categories. But, unlike Bloom’s, these are interactive rather than hierarchical (see Figure 1.2).

Teachers have found that by using good course design, they can get all six kinds of learning to occur in a single course. In such courses, students are able to:

Understand and remember the key concepts, terms, relationships, and the like (foundational knowledge).

Know how to use the content (application).

Relate this subject to other subjects (integration).

Identify the personal and social implications of knowing about this subject (human dimension: self and others).

Value this subject—as well as value further learning about this subject (caring).

Know how to keep on learning about this subject—after the course is over (how to keep on learning).

But the main point here is that, whether they use Bloom’s taxonomy or this taxonomy of significant learning, good teachers strive for many students to achieve high-quality learning—learning that includes but goes well beyond simply learning the content.

Getting Better Over Time

The real goal of any teacher should be more than just striving to be a “good” teacher. The real goal should be to get better at teaching—year after year after year. Teaching is a profession, and all good professionals know they must work continuously to improve their competence in whatever they do.

Professional educators need to recognize that, like everyone else, they have the potential to improve as a teacher. If you ask award-winning teachers whether they can get better, they inevitably say yes. If there is room for improvement in their teaching, there is definitely room for the rest of us to get better as well.

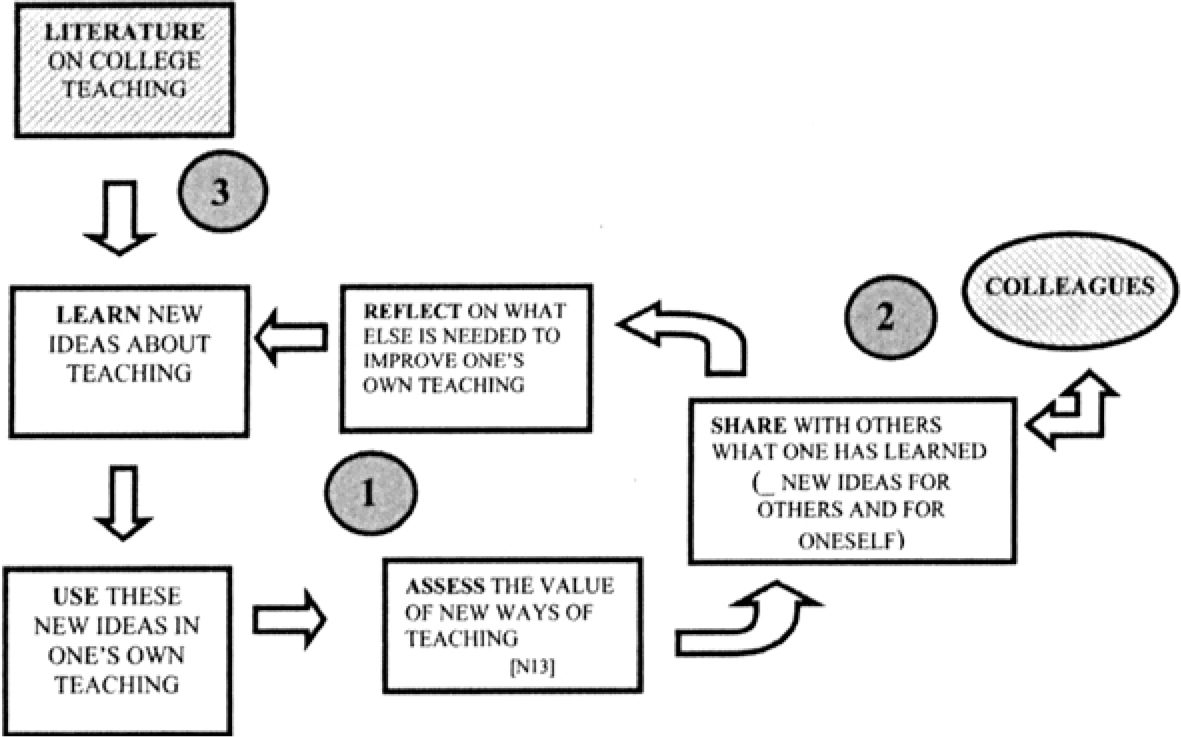

Teachers who do get better over time regularly engage in a set of specific activities that I call “The Cycle for Improving Teaching,” shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 The Cycle for Improving Teaching Note. The numbered circles indicate three ways by which faculty can acquire new ideas about teaching and learning.

Figure 1.3 The Cycle for Improving Teaching Note. The numbered circles indicate three ways by which faculty can acquire new ideas about teaching and learning.The cycle begins when a teacher:

Acquires a new idea about teaching or learning. Professors can and usually do learn from their own experience when they observe and analyze their own teaching (Circle 1). They can also acquire new ideas from talking with colleagues, participating in workshops, and the like (Circle 2). However, there is a rich literature on college teaching that has grown exponentially in the last 15 years. This is what most professors are not accessing but need to (Circle 3). See Fink (2005) for a review of some of this literature, a list of the books and associated ideas that have been especially valuable to me.

Uses that idea by changing something in their teaching. Without changing something, it is not possible to improve.

Assesses the change by collecting and analyzing information from the course. This allows them to know whether the change improved something or not (e.g., the quality of student learning, more engaged students, greater joy in teaching, etc.). Only then can they make a good decision about whether to keep the change or discard it.

Shares by engaging in dialogue with colleagues about teaching. Sharing may take place either informally or formally as in conference presentations or journal articles. Formal sharing constitutes the scholarship of teaching and learning and has the potential to benefit both the presenter and the recipient of the sharing.

Reflects on what else they might learn that could improve their teaching.

Begins another round of the cycle.

Integrating the Three Factors Involved in Good Teaching

The three factors that we have just examined are linked to each other in important ways, as shown in Figure 1.4.

The teacher’s ability to adequately perform the fundamental tasks of teaching affects the quality of students’ learning experiences. And feedback on the quality of both these factors can and should shape the professor’s efforts to improve. The goal is for this cycle to continue—year after year after year.

Now that we have a basic understanding of the Model of Good Teaching, we are ready to use it as a basis for constructing new procedures for evaluating teaching.

Procedures for Evaluating Teaching

The most common way of evaluating teaching at the present time is to use student questionnaires. To be sure, the systematic gathering of information from students is preferable to no evaluation system at all or to letting the department chair base his or her evaluation on one or two random conversations with students. However, student questionnaires have significant limitations as well. First, students only have information about one part of teaching, not the many dimensions identified here. Second, when student questionnaire data are the only data used, they are susceptible to manipulation by teachers who make themselves popular with students by being entertaining, giving easy grades, and so on.

In recent years, more sophisticated procedures for evaluating teaching have been developed and introduced into higher education. One of the best of these is the approach developed by Raoul Arreola (2000). His model calls for academic departments to allocate points to the four role components of teaching that are essentially the same as the four fundamental tasks identified in this chapter. This method is a major improvement over most college questionnaires in two ways: It looks at a broader range of teaching roles and it incorporates information from multiple sources. However, it does not call for information about student learning or about the faculty member’s efforts to improve as a professional educator.

The procedures for evaluating teaching proposed here build on Arreola’s work by adding these two additional aspects of good teaching. As we do this, we will need to pay attention to how we identify:

Multiple dimensions of teaching

Relevant sources of information

Criteria and standards for excellence

Multiple Dimensions of Teaching

Although Arreola used all of the four fundamental tasks of teaching and nothing more, I propose using only two of the fundamental tasks and then adding the other two components in the Model of Good Teaching described earlier.

I suggest dropping “knowledge of the subject matter” and “course management” from the list of fundamental tasks used to evaluate teaching. The reason for this is simply my observation that, for the majority of professors, these two tasks are not the primary bottlenecks to better teaching and better student learning. However, if the leaders in an academic unit believe there are significant variations in these two capabilities that are important enough to affect the teaching and learning process, then they can and should add one or both of these tasks back into the set of evaluation procedures.

I also propose condensing or collapsing the subfactors in the other two major components of this model: “student learning” and “getting better over time.” We can gather information about student learning during and by the end of the course; but getting information about the degree to which that learning “adds value to one’s life after the course;’ while important, is generally beyond the scope of annual evaluations or even evaluations for tenure. Information about the various steps in getting better over time is incorporated into one general report on this aspect of teaching.

Hence, the procedures proposed here call for gathering information about these four dimensions of teaching:

The design of the learning experience

The quality of teacher-student interactions

The learning achieved by students (during and by the end of the course)

The teacher’s efforts to improve over time

Relevant Sources of Information

Before we can start assessing teaching, there must also be a good source of information for each dimension. Because we now have multiple dimensions of teaching, we also need multiple sources of information (Arreola, 2000; Seldin, 1999).

The sources that seem appropriate for each of these four dimensions are shown in Table 1.1.

| Criteria | Primary Source of Information |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Course design materials. Teachers should assemble a variety of materials that reflect how they designed the course. These would include the syllabus as well as examples of assignments and exams. (With the advent of more computer-enhanced teaching, “course materials” will need to include information about the course web site and perhaps reference to off-campus web sites used, such as learning objects from the MERLOT web site.)

Student questionnaires and peer observations. These are in common use now. But if we can develop a more focused rationale for the kinds of teacher-student interactions that are important for promoting high-quality learning, we will be able to formulate questions that give us better information about desirable kinds of interactions. We can also ask peers or faculty developers to observe our classes and provide feedback.

Student learning materials. Teachers should assemble a set of materials produced by students: exams, projects, writing assignments, and so forth. These should include a sampling of A level work, C level work, and F work. We would also want to know what percentage of the students received As, Bs, Cs, Ds, Fs, and Ws.

Teacher self-report and documentation. Teachers should provide a report of their own performance on all four dimensions. A major part of this report should focus on what they did to improve their teaching—what they did to learn new ideas, what they changed in their teaching, how they assessed the impact of those changes—preferably with accompanying documentation.

Criteria and Standards for Excellence

What are needed next are indicators of quality for each of these four dimensions of teaching. This is necessary to answer questions such as: What makes one course design better than another? What makes one set of teacher-student interactions better than another (or better than the same teacher’s interactions at an earlier time)?

Table 1.2 identifies the quality indicators I would suggest for each of these dimensions of teaching. However, individual departments or institutions can modify these or develop their own criteria and standards if they deem it appropriate to do so, still using this conceptual framework.

| Course Design |

|

Interaction with Students (individually and collectively) | Students perceive the teacher as:

|

| Overall Quality of the Student Learning Experience | A high percentage of students:

|

| Improvement Over Time |

|

Developing specific standards. For each dimension and subdimension of teaching, we need to develop specific standards that differentiate higher quality from lower quality teaching. This will be challenging at first because few academics have experience doing this.

The procedures I would recommend for developing these standards are as follows. First, respected members of an academic unit should be selected to do this task, and they should begin by taking time to acquire and develop a shared conceptual framework, one possibility being the framework described here. Second, they should collect materials from their colleagues’ courses as described earlier. Third, they should identify characteristics of the best and worst examples of each criterion. As they do this, they may also want to incorporate ideas from the literature on college teaching that indicate what is “possible” on the high side. This would give even the best teachers something additional to strive for.

To get started, it may work best to just generate two descriptions of high and low quality. For example, the standards for high- and low-quality course design could be described as shown in Table 1.3.

| Low | High |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With time and experience, evaluators will see enough examples of good and bad materials that they will be able to expand the number of categories and become skilled enough to write specific, focused descriptions for each category.

One Disadvantage of this Model—and a Solution

Every method for evaluating teaching has its advantages and disadvantages, and this method is no exception. We need to identify possible problems and try to find solutions.

The biggest problem is almost certainly the fact that this approach will require more time, compared to collecting and rank-ordering student questionnaire data. It will require more time by the teacher to collect and organize all of this information, and more time for someone else to analyze and make judgments about those materials. Is there a solution to this problem?

For me, the solution lies in the observation I hear from most department chairs, that the evaluations of a given teacher do not ordinarily change much from year to year. If this is true, then perhaps we do not need an in-depth evaluation of teachers every year. We could ask teachers to do an in-depth evaluation, say, every two to four years. It might be done annually during the pre-tenure years but only every two to four years after that. And it would always be done when someone is being nominated for a promotion or teaching award. In between those times, teaching could be evaluated in a less time-consuming way (e.g., student questionnaires plus a self-report from the teacher) but in a way that also ensures continued serious attention to the quality of teaching.

A Case Study: Important Lessons

In the 2000 edition of his book on evaluating teaching, Arreola included an appendix that described how Frostburg State University adopted a major change in their procedures for evaluating teaching based on his model. However, at that time, Frostburg State had only begun to use it. Therefore, I contacted the person identified in his book as the principal initiator of that effort, Tom Hawk, a professor in the business college, to see what had happened since then.

First, it is important to note that Frostburg State ended up doing more than what Arreola proposed and less than what I have proposed. In addition to collecting information on Arreola’s four defining roles, they included a call for evidence of what the professors did for their own “professional development as an educator, teacher.” However, they did not ask for specific information about what the teachers changed in their teaching nor about the extent and quality of student learning.

In the business college where Professor Hawk was able to exert some influence, this new way of evaluating teaching did result in a discernible increase in faculty activities in professional development as educators. Roughly 90% of the professors in the management division currently attend at least one workshop on teaching and the majority attends two or more. In the business college overall, he estimates that 65% attend at least one workshop on teaching every year (T. Hawk, personal communication, June 2006). But it has not had the hoped-for impact on the rest of the campus. Why?

First, the faculty’s strong belief in professional autonomy as educators apparently overcame any felt need for professional responsibility and accountability. Hence, the evaluators (chairs and members of the evaluation committee) did not hold professors to a high standard and accepted almost anything as sufficient evidence of “professional development.”

Second, there was a lack of any clear and important connection to rewards. If the people doing annual evaluations and making promotion and tenure decisions do not give real and meaningful weight to high-quality teaching, high-quality student learning, and high-quality professional development, faculty will respond accordingly and allocate their time elsewhere.

Third, there was no strong support for faculty development. Because the institution did not have a well-supported faculty development program, it was difficult for low performing faculty to know what to do to improve. There was also limited institutional financial support to attend conferences and seminars.

Lessons To Be Learned

This case provides several important lessons for other institutions. First, having a more systematic and sophisticated evaluation system did improve the faculty behavior that it focused on—where it was properly applied. Faculty in the business college discernibly increased their engagement in professional development activities. Second, it is essential for upper level administrators (provost and deans) to make it clear that they expect good teaching and that means having and using a good system to evaluate teaching. They need to cultivate a culture that values good teaching. In such a culture, the institutional members are automatically encouraged to know when good teaching is occurring and when it is not. Third, the evaluation system will be stronger if it includes the two features that were omitted at this institution: evidence of student learning and specific evidence of how faculty members actually change their teaching. Fourth, if an institution values continuous professional development, it needs to provide support for it. In this situation, this would mean having a well-supported faculty development program where faculty can go to learn about new ideas on teaching and where they can seek answers to individual questions and problems.

Conclusion

If an institution can accept the ideas embedded in the model of good teaching described here and use the associated procedures for evaluating teaching, that institution is likely to realize three major benefits:

First benefit. The model would provide professors with the tools and motivation to self-assess and improve their own teaching. The criteria themselves would communicate the expectations of the institution. By regularly collecting data on these criteria and reflecting on them, teachers would already know how well they are doing and what needs to be improved. They would also have an incentive to engage in the ongoing professional development that is necessary for them to become increasingly more competent as educators. Hence, over time it should result in significantly better teaching by the majority of the faculty at a given institution.

Second benefit. The model gives academic units and the institution in-depth knowledge of who is really excelling in their teaching, information that goes well beyond “students like them.” This provides a much stronger foundation for annual evaluations, tenure decisions, and teaching awards decisions. With the proper collecting and tracking of this information, it can provide senior administrators with richer and more specific information to share with important outside constituents (e.g., parents of prospective students, donors, and accrediting agencies) about the quality of teaching that is occurring in the institution and how it is improving over time.

Third benefit. Institutional leaders can use these ideas to strengthen the whole institution. At the present time many institutions fall into the trap of valuing what can be easily measured. That is why we have come to value so strongly some easily measurable characteristics (e.g., admission rates, graduation rates, levels of external funding, the quantity of faculty publications). However, effective organizations find a way of measuring what they value.

If indeed we value good teaching as we all claim to, we must find better ways to measure it. To date, we have not known how to do this in a way that is persuasive, either to ourselves or to outside constituents. This chapter addresses that need by offering a new model for defining what constitutes good teaching and new assessment procedures that give a fuller picture of what faculty members do as professional educators.

References

- Arreola, R. A. (2000). Developing a comprehensive faculty evaluation system: A handbook for college faculty and administrators on designing and operating a comprehensive faculty evaluation system (2nd ed.). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Fink, L. D. (2005). Major new ideas that can empower college teaching. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved May 14, 2007, from www.finkconsulting.info/files/ Fink2006MajorNewldeasToEmpowerCollegeTeaching.doc

- Loeher, L. (2006, October). An examination of research university faculty evaluation policies and practices. Paper presented at the 31st annual meeting of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, Portland, OR.

- Seldin, P., & Associates. (1999). Changing practices in evaluating teaching: A practical guide to improved faculty performance and promotion/tenure decisions. Bolton, MA:Anker.

Resources

- The following is a brief list of additional resources that either comment on the need for better procedures for evaluating teaching or provide ideas that can enhance the quality of teaching and learning in higher education.

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2002). Greater expectations: A new vision for learning as a nation goes to college. Washington, DC: Author.

- AAC&U has laid out a challenge and a general blueprint for a liberal education curriculum that will produce “empowered, informed, and responsible” learners.

- Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Many writers have looked at what good college teachers do, but Bain’s analysis of what he found is unusually clear and meaningful.

- Bok, D. (2006). Our underachieving colleges: A candid look at how much students learn and why they should be learning more. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- With the balance and incisiveness that one might expect from the former president of Harvard University, Bok examines eight major kinds of learning in American higher education and finds we are falling short of where we should be.

- Gardiner, L. F. ( 1994). Redesigning higher education: Producing dramatic gains in student learning (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 7). Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Graduate School of Education and Human Development.

- This book provides a good summary of research and ideas about teaching and learning that would, as the title says, produce a dramatically different result in the quality of student learning—if used.

- Hersh, R. H., & Merrow, J. (Eds.). (2005). Declining by degrees: Higher education at risk. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- The DVD relating to this work (available from PBS) interviews professors and students at four representative colleges in the U.S. and discovers major problems. The book provides an analysis of why this is happening.

- Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J. H., Whitt, E. J., & Associates. (2005). Student success in college: Creating conditions that matter. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Kuh, the director of the National Survey of Student Engagement, summarizes lessons from the universities that have used this instrument to show what some are doing that makes them better than most.

- Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Learning and motivation in the postsecondary classroom. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- An excellent summary and interpretation of the research on learning and motivation in higher education.

- Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Weimer suggests that teachers share decision-making power with students, and she notes how that will change the role of the teacher and of the students as well as the function of the content and of feedback and assessment.