14 An Electronic Advice Column to Foster Teaching Culture Change

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

First-year engineering students receive most of their teaching from instructors outside of engineering. As a result, these instructors are typically not a teaching community with a shared commitment to engineering student learning. Retention of engineering students is strongly tied to the quality of teaching, thus addressing collective teaching quality is important. This chapter describes the development of a carefully crafted, electronically distributed advice column on teaching developed by an interdisciplinary editorial team, written under the pseudonym Jonas Chalk. Surveys of Chalk Talk readers indicate that this is an effective means to promote teaching culture change.

Introduction

First year engineering students (FYES) face a variety of challenges as they adapt to college life. Perhaps the most problematic involves the first-year curriculum in which the majority of their coursework is outside of engineering, primarily in chemistry, math, and physics. These courses provide the necessary knowledge base that every engineer needs but are taught primarily by math and science faculty. Thus, the community of instructors who teach these students at this initial, critical point in their engineering curriculum are typically drawn from different departments, each with its own level of emphasis on teaching (versus scholarship and research activities) as a component of its identity. Faculty from math and the sciences often view teaching engineering students as more of a service activity and feel that their teaching energies need to be devoted to students in their own majors. In other words, the instructors of our FYES are too often not a community of instructors at all, lacking a shared sense of purpose, mission, and commitment to prepare engineering students for succeeding courses.

This issue of a shared teaching mission by instructors of FYES is important when one considers the number of engineering students who leave engineering after the freshman year. The well-known study by Seymour and Hewitt (1997) examined concerns among two groups of undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) students: those who changed majors away from science, math, and engineering (“switchers”), and those who remained to complete their respective degrees (“non-switchers”). Poor teaching by science, math, and engineering faculty was cited as a concern by 93% of all students, including 98% of switchers and 86% of non-switchers.

To complement the Seymour and Hewitt (1997) data, Besterfield-Sacre, Atman, and Shuman (1997) developed an attrition model based on student attitudes, particularly their initial attitudes about engineering and their abilities to succeed. They surveyed engineering students at the end of the freshman year using both open-ended and numerical scale items. One item is particularly noteworthy. Using a rating scale of 1 (“does not strongly hold this belief or preference”) to 5 (“strongly holds this belief or preference”), students were asked to rate “Preference for math and science courses over liberal arts courses.” The non-switchers rated this at 4.19 while switchers gave this statement a 3.40. While this result could indicate attitudes developed prior to the first-year experience, it may also reflect the quality and culture of teaching during the first year, when so many of the required courses are in math and science.

Seymour (2002) also noted that there is a change in the STEM classroom activities from the traditional focus on teaching to a new focus on learning. Among a number of implications of this shift, she cited the rethinking of professional relationships among STEM faculty and the restructuring of professional development activities related to teaching, including training for new faculty and “reeducation” of mid-career faculty. Further, a report by the National Research Council (2003) noted the increased level of concern among senior faculty and administrators about improving undergraduate STEM education.

As part of a project to address these issues to promote an improved learning environment for FYES at Northeastern University (NU), methods were needed to build a community of reflective practitioners (Schön, 1983; Wenger, 1998); that is, teachers of FYES who discussed with each other, evolved, and adapted their teaching strategies to meet the needs of this particular group of students. By creating this community of practitioners and a climate of change in teaching practices, we hoped to improve the quality of the learning experience among our FYES. This chapter describes the development of a mechanism to achieve these objectives that took the form of an advice column, much like “Dear Abby.” An editorial team was formed consisting of faculty from chemistry, math, physics, and engineering; members of Northeastern University’s Center for Effective University Teaching (CEUT); and an educational technology specialist. Critical topic areas around the issue of teaching freshman engineering students were identified, and questions on those topics were formulated by the editorial team (as if “readers” had asked the questions). The experiences of the editorial team, as well as the teaching and learning literature, were integrated to compose “responses” to these questions, written under the pen name of Jonas Chalk. The development of the Chalk Talk column provided a means to form the teaching community and disseminate specialized teaching practices for a target population.

Background

The College of Engineering at NU was faced with a number of significant obstacles in addressing communication and teaching among STEM faculty. Communication about teaching between the Colleges of Arts and Sciences and Engineering was limited, usually confined to deans, associate deans, and some course coordinators. Instructors’ knowledge about learning theory and educational research was typically nonexistent except for those instructors who had been involved in education grants. Perhaps the biggest challenge is that, in general, change itself is difficult, and changing ingrained teaching practices is even more so. For the most part, many instructors are comfortable with their teaching. This level of comfort often leads to rote classroom practices with little questioning or reflection on teaching methods.

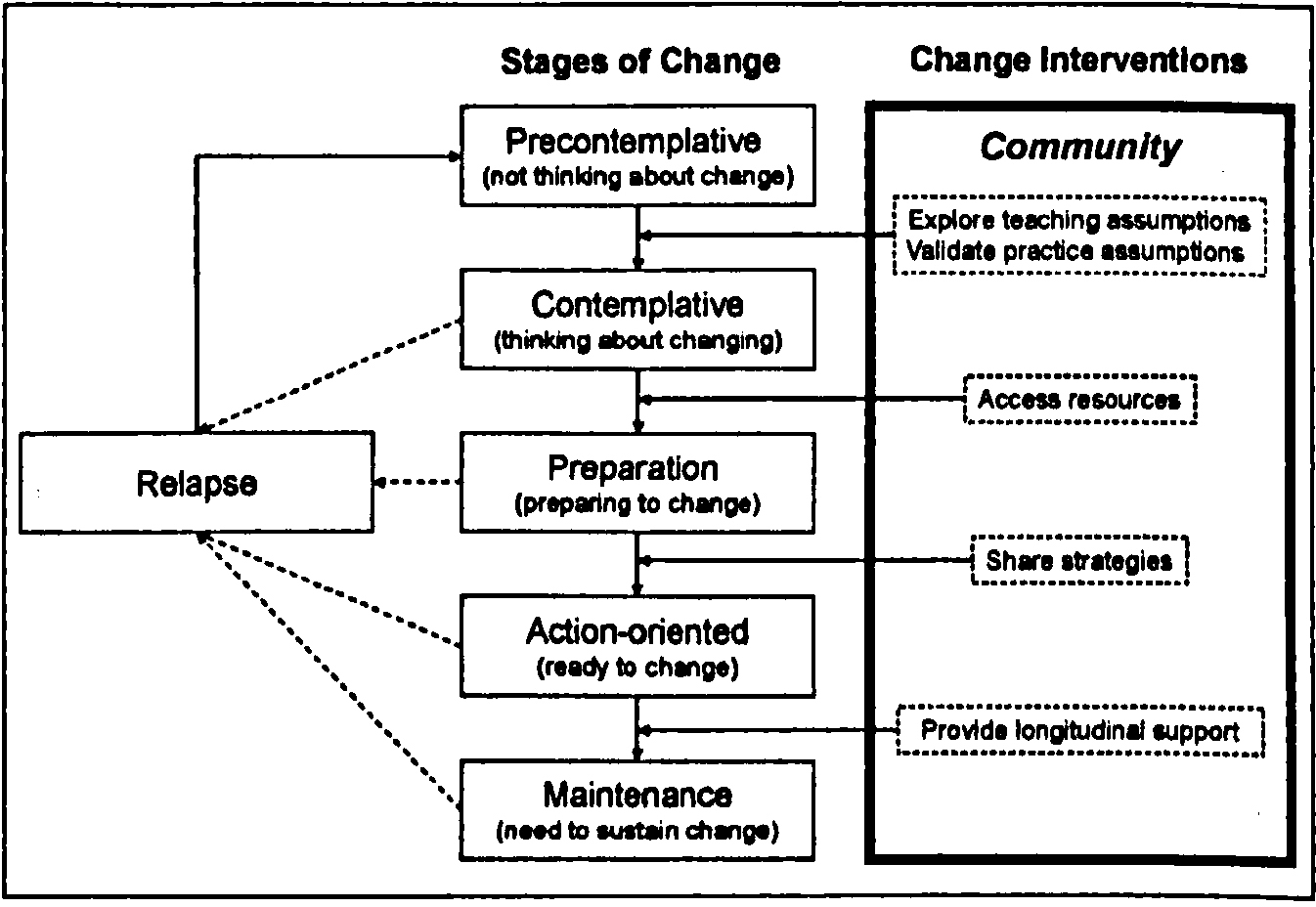

Our task became one of creating an awareness and mechanism for change in teaching practices with our instructors, some of whom were faculty with many years of teaching experience. The literature on change reveals that change often occurs in stages (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Figure 14.1 shows a model of such change adapted to faculty development, where the center set of boxes indicates stages through which an instructor progresses as his or her teaching awareness and approaches evolve. As shown in the right-hand “Community” set of boxes, it is vitally important for the community in which the instructor works to provide necessary support to move through these various stages of change. A final component of this model is shown on the left—that an instructor is prone to so-called relapse at any stage. When this occurs, the instructor may stop pursuing teaching improvement and reflection on his or her practices. This relapse can result in a return to a so-called precontemplative stage, at which point the instructor will need to reinitiate the progression.

Depending on an instructor’s place on the “Stages of Change” continuum shown in Figure 14.1, different interventions will be needed to facilitate further change. Many faculty, especially those who have not been reflective or are not invested in a course or major, fall into the precontemplative stage; that is, they see no reason to change and need mechanisms through which they can begin to explore their assumptions and beliefs around existing practices. Faculty at this stage are not likely to seek help with teaching or try classroom innovations unless they can be convinced otherwise. Precontemplative faculty usually do not come to workshops, brown-bag lunches, or join learning communities; they see no relevance of these activities to their teaching or their other responsibilities such as research and scholarship in their discipline area. Further, math and science instructors may be far less interested in teaching engineering students than their own majors or may not relate to engineering students’ content needs and learning objectives as compared to those of their own students. Convincing precontemplative faculty to move to the contemplative stage necessitates an intervention that attracts their attention and then simultaneously causes them to question and reflect on their teaching practices. This was the goal of the team that developed the Chalk Talk columns.

Figure 14.1 Stages of Change in Teaching Attitude Note. Adapted from Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992.

Figure 14.1 Stages of Change in Teaching Attitude Note. Adapted from Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, 1992.Solution to Create Change

A significant constraint on the design of our method for promoting change was time and efficiency. An intervention had to be developed that would meet the needs of as many instructors as possible on the “Stages of Change” continuum with relatively little cost on their part in both time and energy. With this in mind, the idea of an electronic advice column emerged, which was named Chalk Talk. The editorial team consisted of an interdisciplinary group from chemistry, math, physics, and engineering, as well as from the Center for Effective University Teaching (CEUT) and the Educational Technology Center. These individuals met to exchange practical ideas and talk about different discipline models of teaching and learning (Donald, 2002). This created a forum for significant reflection and dialogue on teaching among these constituents. Next, the group (collectively calling themselves Jonas Chalk) investigated, read, and utilized the research on teaching and learning provided by the CEUT staff to inform the writing of the columns and combined this information with reflection and discussion on our own successful practices. This process allowed a wider variety of faculty to have access to the latest research on learning and teaching as well as the benefit of peer experience.

The method of delivery was in electronic format via weekly email, and columns were posted and remained available on the Chalk Talk web site (http://gemasterteachers.neu.edu/chalktalk.htm), which allowed easy access for faculty consultation. The titles of the columns were specifically designed to attract the faculty’s attention so that they would open at least a few of them, particularly since the columns addressed very common teaching issues strategically placed at appropriate times in the semester. For example, during midterm exams, Jonas would run a column on cheating on tests or devising multiple-choice exams. These were issues that even the most seasoned practitioners usually struggled with at some point in their own classrooms. The use of an electronic dissemination tool provided the means to address significant faculty development issues while creating an interdisciplinary (albeit virtual) community of teachers. By sustaining this flow of information founded on the experience of the editorial team and current teaching and learning literature, we hoped to promote a culture of teaching excellence for FYES. Part of this process was helping FYES instructors understand the learning style for this student group as well as the needs of each discipline involved in the first-year engineering experience.

It was challenging for the team to “become Jonas,” with a single coherent voice (Master Teaching Team, 2004). Each week, the editorial team met to discuss possible column ideas. A first-draft writer was usually assigned to compose the initial “question” and response that would address the particular issue that had been agreed upon. This initial draft was then passed electronically from one team member to the next, with each member editing by using the tracking function in Microsoft Word. At the end of this process, the draft writer typically sorted through the changes and made final edits. This final draft was discussed in great detail and with great passion at the following week’s meeting. These intense conversations led to the development of another feature that was added to Chalk Talk to increase the likelihood that faculty would try something different. We added a postscript to all columns titled “Quick Tip.” The team wanted to provide a tool/method that an instructor could try immediately at his or her next class, or a reference (usually a web site) that would provide further guidance on a topic. The Quick Tip was a means for Jonas to propel instructors into the action stage of Figure 14.1. A typical column is shown in Figure 14.2.

Chalk Talk was launched as a teaching advice column on February 13, 200I. The first column, “Lost Students,” addressed the issue of engineering students who were “lost” in their math and science classes because of varied high school preparation. From this beginning, the Chalk Talk editorial team began producing a column every week for two academic years. These were sent to a freshmen instructor email list, which initially included about 35 instructors in chemistry, engineering, math, and physics. In year three, after two years of producing weekly columns, Jonas decided to run a new column every other week and reprint a relevant archived column on the alternate weeks. This was an effective strategy as Chalk Talk continually attracted new readership in successive years outside of the initial disciplines. These republished columns had a two-fold effect: they allowed new subscribers to read those columns directed toward recurring teaching challenges and, for existing subscribers, the archived columns provided reminders and reinforcement, important deterrents to relapse.

The creation of Chalk Talk provided a venue for regular, face-to-face communication among the chemistry, math, physics, and engineering faculty, many of whom are involved in teaching FYES. Often, problems that arose with teaching or other instructor-student interactions were resolved using the editorial team as a sort of mediation group. Discussions during Chalk Talk editorial meetings allowed teaching and related administrative issues to be addressed in a collaborative setting, often leading to genuine institutional change that benefited FYES. For example, while discussing a column on final exams, it became clear that the existing exam schedule was not acceptable to the teaching faculty in math, science, and engineering. Discussion of the column allowed this issue to surface and led to ongoing talks to create a compromise solution implemented by the registrar the following semester.

The Impact of JONAS

Although attributing any one intervention to improved retention or culture change is difficult, data collected indicate that the freshman-to-sophomore retention for NU engineering students rose from 73% to 79% over the three-year period that the Chalk Talk column has run. We surveyed our targeted readership of faculty, instructors, and teaching assistants from math, science, and engineering after the columns had been published for five academic quarters. The survey, distributed in spring 2002, was intended to find out how many of our email list recipients were aware of Chalk Talk and, more importantly, how many of those were actually reading the column. The survey also asked about the usefulness of the column for changing classroom practices and getting precontemplative faculty to think about changing their practice, the first crucial step in the change continuum. Surveys were sent via email, as part of the Chalk Talk column, and paper versions were handed out at a luncheon to 50 science, math, and engineering instructors who teach FYES. Our survey generated 25 respondents for a 50% return rate from all the disciplines involved in the project. Respondents ranged from lecturers and teaching assistants with only limited classroom time to full professors with more than 20 years of teaching experience.

Of the respondents, 96% were familiar with the column, 92% had actually visited the Chalk Talk web site and found Jonas helpful, and 59% had spoken to another colleague about their teaching because of a Chalk Talk column. Perhaps the most impressive survey result was that 92% of survey takers had thought about their teaching practices and tried at least one new idea. In the portion of the survey where respondents could write comments, 10 faculty members responded. It was clear from their responses that Jonas had prompted these instructors to reflect (or contemplate) on their teaching methods. For example:

“[Jonas] helped me recognize some of the philosophies I hold and the techniques I use.”

“[Jonas] helped me think about things [and] caused me to consider how I do things and possible techniques I can try.”

“[Jonas columns] cause one to reflect on one’s own teaching and what one could do better to improve teaching, how to interact better with students and how to be more effective as a communicator and teacher.”

These comments provided emerging evidence that the columns were prompting teachers of FYES to be contemplative or reflect on the assumptions underlying their teaching practice. For those in the action phase, the columns provided a variety of techniques from different disciplines that instructors could experiment with in their own classes. The action phase was also being reinforced by the Quick Tips provided as a postscript to each column.

There was further on-campus anecdotal evidence that Jonas was gaining some notoriety among the target audience. Teaching practitioners started to ask who Jonas Chalk is (when, in fact, “he” is really a product of 8 to 10 editorial team members). There were also unsolicited responses to columns from the readership, including comments on points of debate in the columns, suggestions about how to address a particular issue, and recommendations for future columns (which were welcome inputs to an editorial team that occasionally struggled with ideas for column topics).

As word of Chalk Talk has spread, we have added more than 200 faculty from five different colleges in our university to our email subscriber list. For example, the Bouvé College of Applied Health Sciences at NU, faced with similar issues teaching their first-year students, was so impressed with the results that the Chalk Talk column is now sent to faculty teaching their firstyear students.

With increased readership we decided to send out a second survey in fall 2004 (see Figure 14.3). The purpose of this survey was to track the readership’s progress along the change continuum. Our questions measured awareness and reflection (pre-contemplative to contemplative), implementation of new techniques (action to maintenance), and abandonment of techniques (relapse). We also asked opened-ended questions to see what effect, if any, reading Chalk Talk had on teaching. This survey was sent as an electronic survey embedded in a Jonas column to the 140 faculty then on the Chalk Talk email list. Along with two subsequent weekly columns, a reminder was posted at the beginning of each column prompting faculty to respond to the survey. The following week the survey was again sent electronically to the entire list. Twenty-seven readers responded for a 20% return rate. The respondents included eleven professors, four associate professors, two assistant professors, four academic specialists, one teaching assistant, and five who classified themselves as other. Results from this survey reinforced our intuitive belief that the columns were a useful mechanism to facilitate faculty movement through the stages of change. Table 14.1 shows the responses to the Lickert scale questions. Before reading the columns, faculty varied in their comfort with their current teaching practices (2.85), but identified the lack of knowledge of alternatives (3.35) and the concern over student reaction to change (3.42) as the two most important barriers to trying something new in the classroom. The questions referring to stages of change showed that after reading Chalk Talk respondents were more aware of teaching issues, learned new ideas/methods and techniques, and had tried new approaches. In other words, Chalk Talk appears to be supplying the necessary elements to overcome barriers to change.

| Frequency of responses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | No Opinion | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean |

| Prior to reading Jonas . .. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1) I was comfortable with my teaching practice and didn’t think about changing it. | 4 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 2.89 |

| 2) I thought about trying new ideas/methodologies/techniques, but it/they seemed too time-consuming to actually implement. | 1 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 2.96 |

| 3) I thought about trying new ideas/methodologies/techniques, but was unsure how to implement it/them. | 1 | 7 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 3.37 |

| 4) I thought about trying new ideas/methodologies/techniques, but was concerned/uncertain about how my students would react. | 1 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 4 | 3.44 |

| After reading Jonas . . . | ||||||

| 5) I became more aware of issues in teaching that I had not thought about before. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 11 | 4.22 |

| 6) I learned new ideas/method /techniques to enhance my teaching. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 15 | 4.44 |

| 7) I tried some new approaches because of the Jonas Chalk column. | 0 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 6 | 3.96 |

| 8) I tried one or more teaching approaches and abandoned it/them because it/they didn’t work. | 1 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 2.74 |

| 9) I tried one or more teaching approaches and abandoned it/them even though it/they did work. | 3 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2.44 |

Perhaps more illuminating were the qualitative results. In answering the question regarding the influence of reading Chalk Talk on classroom teaching, analysis of the data using the check code methodology of Miles and Huberman (1994) revealed the following themes. These themes show emerging evidence that Jonas is providing a virtual community of learners for our readers. Respondents told us that Jonas decreased their isolation as teachers and validated their teaching practice, which made them more confident as teachers.

“It is very nice to know that other instructors [are] faced with some of the exact same issues. As I read each issue, I either feel confident about how I have handled situations in the past or need to address in my teaching.”

“[The column helps m]ostly by giving me more confidence. Seeing discussions of various issues that have arisen with other teachers gave me support in my own responses to those issues.”

A second theme that emerged was the increased awareness and reflection that reading Chalk Talk provided for these teachers. Readers told us that reading Chalk Talk provided them with the insight that, as one reader put it, “makes me think about and evaluate the effectiveness of my approach,” or that “it is a constant reminder to assess my teaching.” One reader summed it up this way:

“[Reading Chalk Talk] heightened awareness that one size does not fit all and that effective teachers address the diverse learning styles of their students. I was one of the education reformers who was too quick to label some teaching techniques ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ After a more thoughtful review, it has become clear that there are many approaches to effective teaching. The key is to be constantly examining my practice, trying out new approaches, and fine tuning old ones.”

Jonas also strongly addressed the lack of knowledge about teaching alternatives as the third theme. The most highly rated sections of Jonas were the Quick Tips and the editorial tone of the columns that emphasize multiple approaches and solutions to the initial question. One faculty member told us:

“[The most helpful part is] multiple techniques, so that I can try a couple of approaches, if one doesn’t work for me or the students.”

A final unexpected and emergent finding was the ability of Chalk Talk to encourage instructors to consider students more consciously in the teaching and learning process. Respondents stated that they were “aware of students’ needs as individuals,” “provided me with a more sympathetic view of my students,” and “I ... more easily put myself in the shoes of my students to try to assess my effectiveness.”

Lastly, Jonas provided inspiration to some and at least renewed faith in their university for others:

“I have learned several classroom management techniques and some participation techniques. It is also inspiring to read the techniques of a master and try to bring the same attitude, if not actual techniques to my classes.”

“I can’t say that Chalk Talk has had much of a direct influence. However, it is very important for me to be at an institution that cares enough about teaching innovation to sponsor something of this sort.”

While the response rate was lower than hoped for, there is evidence that this format has provided the needed mechanism to begin to break down barriers to change and to create an electronic virtual community of teachers to provide the information, support, and confidence needed to change and sustain a new teaching culture.

Conclusion

This chapter describes an electronic dissemination tool for improving teaching practices and changing teaching culture for instructors of first-year engineering students. The tool took the form of an “advice column” for instructors, and each column provides carefully crafted guidance on a particular teaching issue, written by an editorial team of eight to ten faculty and staff. The columns were distributed via email to instructors in chemistry, math, physics, and engineering. The goal was to build a community of reflective practitioners and effect teaching culture change with increased awareness of teaching beliefs and collegial interactions among faculty from different schools. The model for change was based on that of Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross (1992), with the objective to encourage a more action-oriented teaching culture—one in which instructors are inspired to try new methods and reflect on the results.

The results of the column, after three years of dissemination, have been significant. While the results cannot be attributed exclusively to the Chalk Talk initiative, freshman-to-sophomore engineering student retention at NU has increased from 73% prior to the start of the column to 79% in 2003.

The number of faculty enrolled in the email list has increased from about 35 at the column’s inception to 140 in 2004 to 227 in 2005. In the first survey of target instructors, 96% were familiar with the column, and 92% had thought about their teaching practices and tried at least one new idea. The second survey showed strong evidence that readers of the column are supported as they proceed through the stages of change. Most particularly, the column has contributed to raising awareness of practice assumptions, the first critical step in moving from precontemplation to the beginning stages of change.

While Jonas may not have opened the classroom door (i.e., made teaching practices transparent to all [Shulman, 1993]), the Chalk Talk column has created an electronic teaching community among disparate disciplines. It has provided an inspiration to act and reflect on teaching practices and serves as a forum for continuing discussion.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the support of a grant from the General Electric Foundation, “GE Master Teachers for Freshman Engineering Students,” which has partially supported the development and perpetuation of the Chalk Talk column. The efforts and congeniality of the members of the editorial team are also greatly valued. We appreciate the support of Allen L. Soyster and Richard J. Scranton, dean and associate dean of engineering, respectively, and James R. Stellar, dean of arts and sciences, for sustaining this ongoing initiative.

References

- Besterfield-Sacre, M. E., Atman, C. J., & Shuman, L. J. (1997). Characteristics of freshman engineering students: Models for determining student attrition in engineering. Journal of Engineering Education, 86(2), 139–149.

- Donald, J. G. (2002). Learning to think: Disciplinary perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Master Teaching Team. (2004). Becoming Jonas: Reflections from the team. In D. M. Qualters & M. R. Diamond (Eds.), Chalk talk: E-advice from Jonas Chalk, legendary college teacher (pp. 11–20). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- National Research Council. (2003). Evaluating and improving undergraduate teaching in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Seymour, E. (2002). Tracking the processes of change in U.S. undergraduate education in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology, Science Education, 85(6), 79–105.

- Seymour, E., & Hewitt N. M. (1997). Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Shulman, L. S. (1993). Teaching as community property. Change, 25(6), 6–8.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.