16 The Graphic Syllabus: Shedding a Visual Light on Course Organization

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Students rarely understand how a course is organized from the week-by-week topical listing in traditional syllabi. This chapter explains a teaching tool called a graphic syllabus, which elucidates (and may improve) course design/organization and increases student retention of the material. It may resemble a flow chart or diagram or be designed around a graphic metaphor with another object. Included here are materials, experiences, and graphic syllabi from a workshop conducted several times on how to compose one (involving about 115 faculty and faculty developers). Graphic representations of text-based material appeal to the visual learning preferences of today’s students and complement distance and computer-assisted learning as well as traditional classroom instruction.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes both a tool for enhancing student learning and the faculty workshop conducted to explain and enable faculty to use it. Winner of the Professional and Organizational Development Network’s (POD) 2000 Bright Idea Award, this tool is called a graphic syllabus. In it simplest form, a graphic syllabus is a flow chart, diagram, or graphic organizer of the topical organization of a course. It is typically a one-page document included in a regular text syllabus, preferably right after the week-by-week (or class-by-class) list of course topics and assignments.

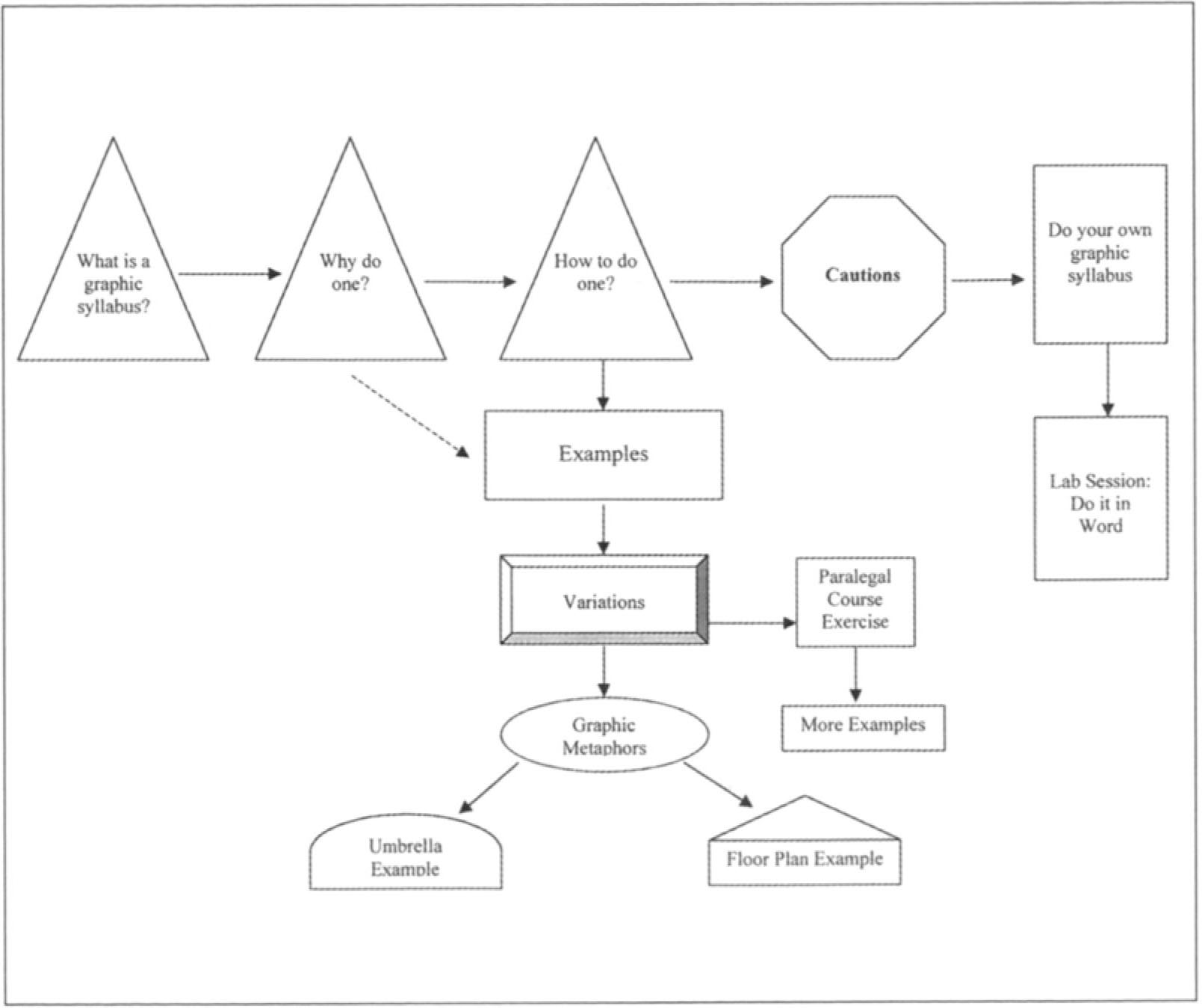

Since the graphic syllabus is a visual tool, it may be best understood inductively, intuitively, and holistically by viewing examples. So the workshop does not open with a definition. After considering some general syllabus advice (a three-page checklist of recommended information to include and some strategies for ensuring students read a syllabus at all), participants review a fairly simple graphic “syllabus” of the workshop itself, shown in Figure 16.1. This first illustration is done in MS Word, which is the software the participants use during the last hour of the three-hour workshop (see Appendix 16.1 for software options).

As participants are examining the figure, they are asked what patterns they detect in the graphics, such as the shape of the enclosures and the overall spatial layout. They quickly notice the relationship between the shapes (the medium) and the text inside them (the message), such as the triangles around questions (What? Why? How?), the stop sign around “Cautions,” and the frame around “Variations.” They also correctly identify the graphic metaphor as a more creative extension that may take on any structure or look. Finally, they see that the bulk of the workshop will be devoted to how to design a graphic syllabus, and that they will design their own.

Indeed, by the end of the workshop, participants have drafted a design of a graphic syllabus for a course they plan to teach in the near future. (This workshop is offered during summer and semester breaks.) The workshop announcement (posted on the all-faculty email list) asks them to bring a current text syllabus with them and promises that they will leave with at least a tentative graphic syllabus of their course.

WHY DESIGN A GRAPHIC SYLLABUS?

Reveal the Method to the Madness

Instructors spend hours, even days, designing a course, including pouring through different textbooks for the one that most closely mirrors their preferred organization of the material. In a sense, a syllabus is a piece of scholarship, one that brings the scholarship of integration to the scholarship of teaching (Boyer, 1990). It seems well worth the effort to present the organization of a course so that students can understand, appreciate, and follow it.

To begin the topic of “Why Do One?” participants are directed to a sample syllabus which whimsically portrays what a typical listing of course topics looks like to many students (e.g., week one: overview of something I gotta take; week two: the composition of apple peel; week three: introduction to giraffe consciousness, etc.). After all, on the first day of class, they know nothing about the issues a course will address or the organization of the field or subfield. At best, they notice repetition of technical terms and flag words like “continued.” Why even read this part of the syllabus when the topical listing makes no sense? And it makes no sense because the topics bear no clear relationships to each other. Students might as well be reading written directions on how to drive from one unidentified, unconnected place to another, with no destination except the end.

Those who routinely review syllabi for faculty in other disciplines should be familiar with this feeling. It’s like guessing from someone else’s grocery list exactly what major meal he or she plans to prepare. How can students acquire and retain knowledge and abilities without having a valid, overarching structure in which to place them?

The workshop materials include the week-by-week listing of topics and assignments from a Social Stratification course I taught (Figure 16.2). The version in the workshop packet is more complete and true to life, cluttered by typical strings of reading assignments from various books and edited volumes, along with advice to students on how to read them. Participants are asked to explain the “organization” they discern in this sea of gray, and they find about as much as my students used to. Then they hear the story of how a graphic syllabus was conceived.

Like so many inventions, the idea was a response to frustration. With no good text available for this course, I developed my course organization from scratch. However, the organization seemed to be invisible to everyone but me. After teaching the course several times, I drew a flow chart of its substantive organization, shown in Figure 16.3, and handed it out to students. While there were no significant results, such as improvements in exam performance, students really studied the document, and some referred to it throughout the term as we moved from topic to topic. A few students in this very large class even commented that they liked it or better understood the course because of it, so I continued using it. At the time, it was very rare to assess a new teaching tool in any systematic way or to share it with colleagues.

Extending the two analogies above, a graphic syllabus is like a well-labeled map to supplement written driving directions or a cookbook picture of the complete planned meal, ordered from salad through dessert. Without word-laden explanations, it reveals exactly how and implicitly why a course is organized in a particular way. It makes the course’s structure evident and shows the big picture: how the trees are arranged to create a forest.

Dual Code the Course Organization

Paivio (1971) forwarded the cognitive psychological theory that we have two long-term memories for the same information, the semantic (verbal) and the episodic (visual), the latter of which most people consider to be their better memory. This cognitive psychological theory has powerful implications for teaching and learning, yet it has received little mention in the college teaching literature (e.g., Tigner, 2000). One obvious implication is the wisdom of dual coding: that material received and processed in both verbal and visual ways is likely to be retained better and longer than material received and processed in only one way. A standard syllabus engages only the semantic memory, if it engages any memory at all. A graphic syllabus ensures coding onto the episodic as well.

Students do not need to learn and remember a course syllabus in itself, but it is important that they retain the organization of the knowledge they acquired. Structure is the glue that holds knowledge in the mind. Without it, knowledge quickly falls away like so many irrelevant factoids.

Reach “Left Out” Learning Styles

At the moment, there are over a dozen different learning-style models in academic currency based on sensory modalities, information processing, multiple intelligences, personality/psychological types, cognitive styles, experiential preferences, and orientations to learning (Theall, 1997). Most of them posit at least one type or style that processes visually presented material more readily than the same material presented in another medium. These types/styles include visual, visual-kinesthetic, concrete, visual-spatial, global, holistic, artistic, intuitive-feeling, and diverger. As a rule, higher education is pitched to the more verbal, digital, rational, logical, abstract, sequential, and analytic types and styles, and so is the standard text syllabus. Adding a graphic syllabus levels the playing field, making the course design and scaffolding visible to those who need to see the plan before they can learn the pieces.

Teach a Learning Tool

Using the graphic syllabus as an illustration, instructors can quickly teach their classes the learning/study technique of mind-mapping, one quite likely to help the more visually-oriented students. (Concept maps and graphic organizers are based on the same idea.) This is assuming, of course, that the overall design is of the flow chart, diagram, or web/spider variety. Developed by Buzan (1991) and popularized by Ellis (2000), mind-mapping has proven useful to many students in outlining papers, taking class and reading notes, and organizing and summarizing material for tests. In-class activities where students fill in or develop concept maps and graphic organizers also make good classroom assessment techniques and test preparation exercises for both individual students and cooperative learning groups (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

For Oneself: Be Creative and Self-Critical

Faculty explore new venues during the graphic syllabus workshops. Some of the most seemingly reserved individuals release a surprising flood of metaphorical creativity and artistic flair. Before designing their own graphic syllabus for a real course, they try their hand at a fictitious one for Introduction to Law for the Paralegal, a real course at certain other universities but an area these participants know nothing about. Working with two or three colleagues, they manually draw their products on large newsprint paper using different colored markers. The different groups develop markedly disparate topical organizations and graphic designs, some using legal icons and metaphors (e.g., scales of justice, courthouse facades). While the graphic syllabi that individual faculty draft for their own real course show more restraint, they still display the participants’ impressive abilities to recast abstract, verbal concepts and relationships in visual-spatial arrangements.

Faculty also report that, in the course of composing a graphic syllabus, they identify problems in their course organization and often decide to rearrange the topics. A few have even deleted units that, when viewed visually, actually lie outside the course flow.

HOW TO CREATE A GRAPHIC SYLLABUS

Workshop participants learn how to create a graphic syllabus first by viewing several examples. In addition to Figures 16.1 and 16.3, they examine those developed by other faculty, most of them from previous workshops (Figures 16.4 and 16.5). What these illustrations show is the tremendous potential for variation and creativity.

The possible variations include

type size, face, and features (e.g., bolding, underlining, italics, software “art” options)

connecting-line direction, length, thickness, color, and pattern (e.g., solid, broken, dotted)

enclosure size, shape (e.g., square, rectangle, triangle, circle, oval, diamond, hexagon, parallelogram, star), shading, color, and borders

general design and shape

For instance, though it is not evident in black-and-white print, Dr. Jan Williams Murdoch’s graphic syllabus (Figure 16.4) reinforces her course’s parallel coverage of “Professional Relationships” and “Relationships with Clients” with different colored boxes, as well as with their parallel spatial arrangement. Dr. Darlene Panvini’s overall branching design suggests the ecological focus of her course, and she highlights her major assignments in shaded boxes (Figure 16.5). Both figures were done in MS Word.

After viewing these examples, participants study Figure 16.6, which shows a wide variety of design motifs for expressing a simple relationship among several concepts, a relationship stated verbally as “When properly implemented, the case method, problem-based learning (PBL), service learning (SL), and simulations all teach students how to apply course material.” Cyrs and Conway (1997) formalized the idea of “constructing word pictures” of sentences and used these and other motifs as illustrations.

AN EXTENSION: THE GRAPHIC METAPHOR

A graphic metaphor is a type of graphic syllabus in which the design is based on an object or set of objects. The metaphorical object(s) may or may not be related to the course subject matter, but the metaphor is especially memorable when a relationship exists. (Recall how Dr. Panvini’s graphic syllabus design “looks” somewhat biological or ecological, and as such it approaches a graphic metaphor.) Either way, however, the metaphor supplies a symbol, a kind of cognitive shorthand, of the course organization that should reinforce students’ recall of the course material.

Compared to a standard graphic syllabus, a graphic metaphor has a distinct downside. As it is more of a drawing than a flow chart or diagram, only those familiar with sophisticated drawing or design software will be able to produce it on computer. For most faculty, the most realistic tools for composing most or all of a graphic metaphor will be the lowest-tech alternatives, such as pens, pencils, markers, crayons, rulers, triangles, T-squares, compasses, cut-outs, and tracing paper. If an electronic version is needed, the hand-drawn creation can always be scanned. A digital sender can even email it as an attachment.

Figures 16.7 and 16.8 show two graphic metaphors of the same course, Free Will and Determinism, a crossdisciplinary freshman seminar I have taught. Both metaphors are “overlaid” on the same visual arrangement of course topics and organizational dimensions (historical time from top to bottom and a philosophical continuum from left to right). They are worth showing here because both metaphors are flexible and adaptable to a variety of courses, whatever the discipline or subject matter. They also allow for plenty of variation in type, color, and many other enclosure features.

Figure 16.9 “Corporate Site” Graphic Metaphor for Budgeting and Executive Control CourseReprinted with permission.

Figure 16.9 “Corporate Site” Graphic Metaphor for Budgeting and Executive Control CourseReprinted with permission.The first metaphor (Figure 16.7) relies on the umbrella as its key object to illustrate how major topics and the various readings are related. Though crossdisciplinary, the entire course falls under the broadest umbrella, the field of philosophy, which also provides most of the early readings. Under philosophy are the major schools of thought involved in the determinism and free-will debate, which indeed has four sides rather than two. These schools, in turn, justify their own smaller umbrellas, with related readings falling under each one. Since occurrences defy explanation under fatalism, it has not inspired scientific study, utopian extrapolations, or clinical approaches, so it has no readings. But it has a popular stepchild, belief in spiritual destiny, which for the most part falls outside of philosophy (and into religion), as shown. Spiritual destiny has spawned many readings, however, including the assigned book. Any course organization built around different approaches, perspectives, or schools of thought may be amenable to the umbrella metaphor.

The second graphic metaphor (Figure 16.8) overlays a floor plan on the arrangement of topics, and the course follows the arrowed line, moving from one room (topic) to another. In fact, the course flow is the dominant graphic. Compared to the umbrella graphic metaphor, the floor plan more accurately reflects the week-by-week course organization. It clearly shows that the course actually backtracks, first visiting three of the four philosophical schools of thought (determinism, compatibilism, and free-willism), then going into late 20th-century genetics, biochemistry, and sociobiology, which exemplify modern scientific determinism. Then the course returns to the fourth school of thought, fatalism. There are good reasons for this turnaround, having to do with the background knowledge that students need for the first paper assignment and the historical chronology that the readings follow from week six on. The result may be graphically messy, but the students never found it confusing. The floor plan metaphor does restrict the enclosures to room-type shapes with cut-out doors, but it need not follow the standard layout of a house or office building.

In two additional examples, the graphic metaphor is related to the subject matter of the course. The first, for a corporate accounting course (Figure 16.9), is a whimsical hand-drawing of a corporate site, with a production facility on the left and an office building on the right. The main course topics appear as labels on the relationships between the two buildings (linking lines) and on the various icons (garbage heap, people, smoke from the smokestack, moneybag, incoming truck, and the sun). The numbers next to topics refer to the chapters in the text. Obviously the graphic doesn’t “flow” with the course organization as a flow chart would; the course organization and reading assignments are not ordered from left to right or from top to bottom. But the picture shows very clearly how the major topics interrelate in corporate accounting operations.

The final graphic metaphor (Figure 16.10) is for an Engineering Graphics course. It is especially memorable because the metaphorical objects—strikingly drawn in three dimensions using engineering graphics software (AutoCAD)—mirror the subject matter, and their spatial arrangement reflects the relationships among topics. Again, however, the course flow is not easy to follow, as one week’s topic may lie spatially distant from the next weeks.

CAUTIONS

The experience of conducting this workshop five times for over 115 faculty has taught me cautionary lessons. Some participants release so much creative energy and have so much fun while composing a graphic syllabus or metaphor, especially while working with colleagues on the fictitious paralegal course, that they seem to lose sight of the ultimate purpose, which is to clarify the course organization to the students. Participants seem to benefit from the following advice before tackling the real thing for a real course.

Avoid overcomplexity, as in PowerPoint presentations and life in general. The graphics should be clean and simple so students focus on the course topics and flow.

Since a course proceeds in predominantly one direction through the semester, so should a graphic syllabus. Instructors should carefully clarify any recursive relationships and double-arrowed lines to students (since time doesn’t reverse itself).

A graphic syllabus shows the structure of the course—not the field, not its major theoretical model, and not its history. Such graphic representations make superb teaching tools and student-learning aids, but none of them should be called a graphic syllabus. To do so will probably confuse students.

An instructor should refer to a graphic syllabus frequently during the course, as one would to a road map on a trip.

CONCLUSION

Graphic representations of text material, such as the organization of a course, are likely to become more important and even expected components of courses, as distance education and computer-assisted classroom instruction grow more commonplace (Cyrs, 1997). Following the lead of primary and secondary education, higher education is taking on a more visual nature, both because web-based and television technologies foster it and because today’s students are well adapted to it, perhaps better adapted to it than to extensive text. In fact, since graphic representations so concisely show the big picture, they make natural image maps and eye-appealing gateways to course information (readings, assignments, class activities, and details of course topics) and online sources of knowledge.

A graphic syllabus is just the beginning. As mentioned above, the organization of a discipline or a field of study, its history, and its theoretical models are ready candidates for recasting into flow charts, diagrams, and graphic organizers. So are many processes in the biological, physical, and behavioral sciences. The crucial elements of a plot or a case may also lend themselves to graphic representation.

Normally, a good syllabus includes a list of student-learning objectives (outcomes) for a course. In a truly comprehensive list, some of these are ultimate (end-of-semester) objectives while others are meditating—that is, objectives that students must meet by a certain time in the semester before they can meet one or more of the ultimate objectives. For example, in order to speak and write in the past tense of a foreign language, students must be able first to speak and write in the present tense. In order to write a research proposal, students must be able to do a great many other things beforehand, including formulate a viable hypothesis, conduct and write a cogent literature review, select an appropriate methodology, and write in a scholarly style. Students could better understand the structure of the course and their own learning as a cumulative, step-by-step process if an instructor laid out their learning objectives in a flow chart format, one showing earlier objectives as prerequisites linked to later ones.

The final suggestion is for academic departments to apply these principles in examining their curricula for possible revision. Faculty members can begin by asking the question, “What do we want our majors to be able to do by graduation?” Once they define these skills and abilities (and they usually have to for accreditation), they can work their way backwards in flow chart fashion to see how the department’s various courses fit in and interrelate to equip students to meet the ultimate objectives for the major. Do the freshmen courses equip students for the sophomore courses, the sophomore courses for the junior courses, etc? Or are their faults in the flow? Are some basic knowledge and abilities not addressed until junior or senior years? Are juniors expected to know how to do something that most don’t learn until senior year?

Such an exercise is neither for dysfunctional departments nor for faint-of-heart and insecure faculty. Visuals have a way of rendering the complex as simple as it really is, thus revealing the truth about structures and systems. They uncover sequencing problems, missing parts, and pieces that don’t fit or aren’t necessary.

REFERENCES

- Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Buzan, T. (1991). Using both sides of your brain. New York, NY: Dutton.

- Cyrs, T. E. (1997). Teaching at a distance with the merging technologies: An instructional systems approach. Las Cruces, NM: New Mexico State University, Center for Educational Development.

- Cyrs, T. E., & Conway, E. D. (1997). Beyond bullets: Let your students see what you are saying. Session presented at the annual meeting of the Professional and Organization Development Network in Higher Education (POD), Haines City, FL.

- Ellis, D. (2000). Becoming a master student (9th ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

- Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston.

- Theall, M. (1997, May). An overview of different approaches to teaching and learning styles. Paper presented at Teaching and Learning Styles at a Distance, Central Illinois Higher Education Consortium Faculty Development Conference, Springfield, IL.

- Tigner, R. B. (2000). Putting memory research to good use: Hints from cognitive psychology. College Teaching, 48 (1), 149-152.

Contact:

Linda B. Nilson

Director

Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation

445 Brackett Hall

Clemson University Clemson, SC 29634

(864) 656-4542

(864) 656-0750 (Fax)

Email: [email protected]

Linda B. Nilson is founding Director of Clemson University’s Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation and the author of Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors (Anker, 1998). She also conducts teaching workshops for faculty across the country. Previously, she directed teaching centers at Vanderbilt University and the University of California, Riverside and was a sociology professor at UCLA. She has recently held leadership positions in Toastmasters International, Mensa, and the Southern Regional Faculty and Instructional Development Consortium.

APPENDIX 16.1

SOFTWARE FOR COMPOSING A GRAPHIC SYLLABUS

Any graphic syllabus that resembles a flow chart—whatever its flow direction, enclosure shapes, colors, type variations, etc.—can be done in MS Word or PowerPoint. In Word, the graphic options are found on the Drawing Toolbar, which are also accessible by clicking on Insert, then Text Box, Symbols, and Picture. Under Picture, there is a wide array of graphics in AutoShape, ClipArt, and WordArt. (Adjustments can be made by clicking on Draw.) In PowerPoint, the key tool is Org Chart.

Commercial options in concept-mapping/graphic-organizing software are readily available. No software package actually designs a graphic; it is still the instructor’s task either to design it from scratch or to select among templates. For instance, Inspiration, the most popular among academics and K–12 teachers of those listed below, transfers text from an outline to a flow chart, concept map, or web, and offers 35 templates to chose from. The instructor then “draws” the links and adds text to them. Generally, the more flexibility a package allows, the more complex and difficult it is to use. Educational prices vary from about $50 to over $200 (estimates only because some companies don’t specify the educational discount), and most companies give a free, 30-day trial download. However, trial copies may not permit printing or saving. Here are some leading options.

Inspiration: www.inspiration.com

Pacestar: www.pacestar.com

Magin: www.maginsoftware.com

Desktop Brain: www.thebrain.com

Enquire Within: www.EnquireWithin.co.nz/expertma.htm

Decision Explorer: www.banxia.com/index.html

VisiMap and InfoMap (Lite): www.coco.co.uk

CorelDRAW: www.corel.com