2 A Brief History of Educational Development: Implications for Teachers and Developers

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

An historical review of the practice of educational development identified four belief systems about teaching and learning that shape the practice. Each system is characterized by an assumption about the teacher’s role: content expert; performer, who makes learning happen; facilitator, who encourages learning through interaction; and helper, whose relationship with learners is a vehicle for learning. The good news is that even teachers who are limited to only one of these belief systems can be successful. On the other hand, developers must have an appreciation for more than one belief system if they are to be successful at helping teachers.

INTRODUCTION

I was honored by the invitation to give a plenary lecture at the 25th anniversary meeting of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education (POD). A historical paper should be ideal for this occasion but I was concerned about my lack of professional training in history. My biggest worry was the pitfall of historical determinism. I winced at the prospect of my discovering a hierarchy of historical stages in the practice, leading up to the highest form, which just happened to be my perspective. Developmental theorists seem to place themselves at the top of their hierarchies.

I was encouraged when Bill McKeachie, who lived this history, and Karron Lewis (1996), who wrote a history of the field in the United States, confirmed the trends that I had identified. It was also gratifying to reach conclusions that were not hierarchical, at least for teachers. Indeed, my conclusions echoed those of Daniel Pratt (1998), namely that diversity in teaching roles can be celebrated. That felt right. I would not trust a conclusion that blamed the teachers for their limitations. On the other hand, the implications for developers turned out to be provocative, unpleasant, and risky. There appears to be a hierarchy of faculty developers and I am not at the top of it. That felt right too. I am always suspicious of conclusions that do not wound the pride. With that enticement, let me tell the story. I will argue that there are four belief systems about educational development: content mastery, skilled performance, facilitation of learning, and personal engagement, each with its own historical trajectory–a beginning, a peak, and a decline.

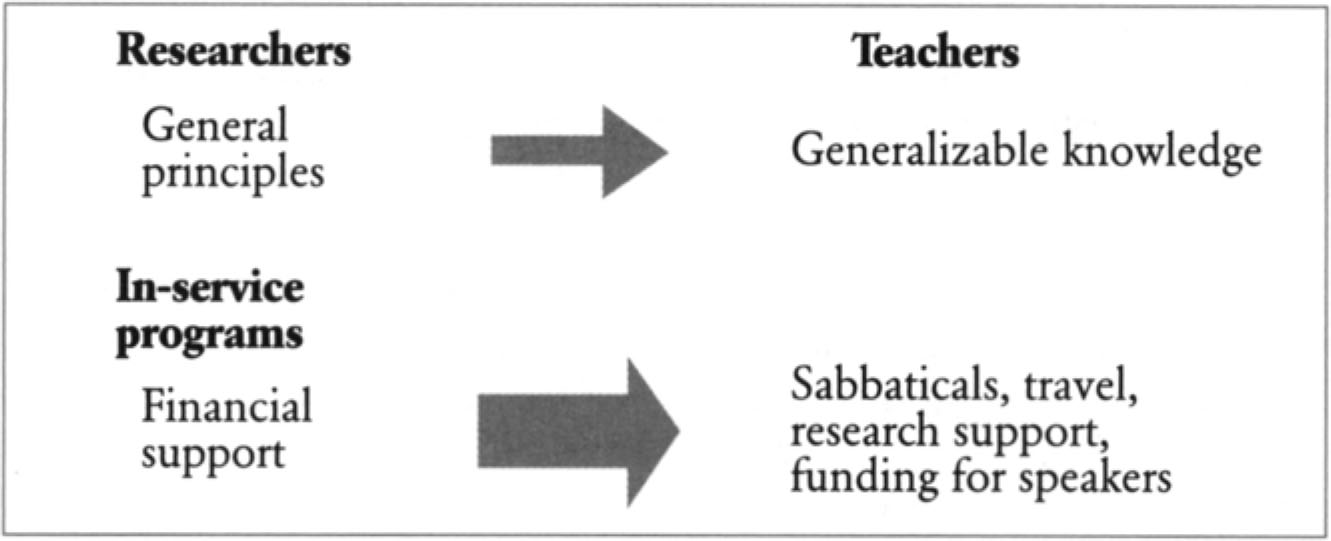

BELIEF SYSTEM I: TEACHING AS CONTENT MASTERY

Imagine that it is the 1950s and you are a university professor who would like to improve your teaching. What would you have found? About half of you would have found some kind of formal in-service program for faculty in your college or university, according to a survey of 1,000, 4-year colleges in the United States. The most active programs were those that helped professors maintain their academic specializations (Many, Ellis, & Abrams, 1969). You might have been given funding for sabbatical leave, travel to professional meetings, research support, or guest speakers. Both the administrators who gave this money and the teachers who received it believed that such funding was an appropriate means of teacher development because they shared a common belief system about the role of teachers, one which I will call “content mastery.” This belief system began before WWII and was the dominant belief system in the 1950s. Although it waned in the 1960s, it is still with us in some forms (Figure 2.1).

The beliefs about the teacher’s role that dominated this period were the traditional academic folklore captured by the following slogans: teachers are born, not made; teaching is an art, not a science; a professor’s classroom is his castle; hire good people and get out of the way (Gaff, 1975). These sayings implied that little could be done to improve the teaching of professors. Teachers were expected to be masters of their specialty and need not be a master of teaching. The teacher-learner relationship was impersonal and formal. The belief system supported the concept of division of labor: “My job is to deliver the lecture and to test the learners. Their job is to learn.”

Although educational development was predominantly something administrators did for teachers, educational researchers and developers did exist. Research on college-level teaching during this period used the methods of experimental psychology, mainly tightly controlled experiments, to yield behavioristic principles. Their expectation was that their research would yield a body of general principles that would flow to teachers where it would be applied to their practices. The product of this research was available to teachers but not very accessible. In my experience few teachers read it. There was a radical separation between teachers and researchers during this period.

Indeed, the early 1960s marked the decline of this period and introduced the first faculty development units, beginning with the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching in Michigan in 1962.

During this time, research was published in journals that live on Donald Schön’s (1995) high ground where manageable problems lend themselves to solution through the use of research-based theory and technique. Sociology, psychology, and education journals by specialists topped the list, for example, The Sociology of Education, The Journal of Higher Education, The Journal of General Education, College Teaching, and The Bulletin of the Association of American Colleges.

Toward the end of this period books on university teaching were beginning to appear. These books went beyond providing generalized principles of learning. They addressed specific skills, including sensitivity, relationship enhancement, and small group learning. The following list includes some of the more popular ones: Teaching Tips: A Guidebook for the Beginning College Teacher (Wilbert McKeachie, 1951); College Teaching: A Psychologist’s View (Claude Buxton, 1956); Two Ends of the Log: Learning and Teaching in Today’s College (Russell Cooper, 1958); Learning to Work in Groups: A Program Guide for Educational Leaders (Matthew Miles, 1959); Handbook of Research on Teaching (Nate Gage, 1963); Teaching Methods in Australian Universities (Australian Vice Chancellors Committee Report, 1963).

Finally, in those early days, a small number of people were engaged directly in the improvement of teaching and learning. They were mostly psychologists who attempted to apply basic research to the teaching and learning process. We did not call ourselves “developers” and our clients were often disappointed. Upon entering the seminar room to attend a typical session that I presented to teachers, you would have seen on the black board the inverted “U” relationship between performance and arousal (from my work in the lab of the motivation psychologist Dan Berlyne). An exuberant young man with jet-black hair would have explained, “You see, students who have too high or too low an arousal level will not learn as well or perform as well as students who have an intermediate arousal level!” The silence that followed I interpreted as thoughtful interest until one teacher asked how he could detect where his students were on the arousal curve and what could he do about it, anyway? My response was to explain that we know the rats’ arousal level because we starve them. Eventually I came to realize, along with the rest of the field, that faculty need more than general principles. They need specific skills, contextually grounded.

Although content mastery has become less popular, it is still present.

Dr. Kontent (not her real name) is the only physician in a geographic area with expertise in child psychiatry. She asked the university department not to send residents to her since she was not interested in teaching. Residents waste her time and she does not get paid for it. Since Dr. Kontent was the only child psychiatrist in town, the residency coordinator sent residents to her site anyway. Residents joined the team at which clinical issues were discussed, interacted among themselves, asked questions, and observed. They learned something in the setting although Dr. Kontent did almost nothing to accommodate them.

Now imagine that it is 1970 and you are a university professor who would like to improve your teaching. In the 1950s you would have been unlikely to find an educational development office or program at your institution, but by 1975 you would have been very likely to find one due to an explosion in faculty development programs in the early 1970s. Although there were fewer than 50 faculty development programs in the United States at the end of the 1960s (Sullivan, 1983), by 1975, 41% of all four-year institutions had faculty development programs (Centra, 1976).

This growth was driven by the campus unrest of the 1960s, an influx of challenging students (older, ethnically diverse), the stagnation in new hiring, and new discoveries about learning and memory by cognitive science. You probably would not have found funding to upgrade your competence in a subject area, but you would likely have found people eager to help you acquire a wide range of competencies, including knowledge, attitudes, values, motivations, skills, and sensitivities. A transformation had taken place in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the normative beliefs about the role of teaching. According to Gerry Gaff (1975), this transformation was characterized by the emergence of a new set of assumptions about the role of teacher: The belief that instructional competencies are learned; that these competencies include a complex set of knowledge, attitudes, values, motivations, skills, and sensitivities; and that teachers had a responsibility to learn the competencies.

The new developers tended to fall into one of two camps identified by their dominant beliefs about the role of the teacher and by the kinds of skills that were the focus of their efforts. Both of these belief systems had been developing in the 1950s and 1960s and would peak in the 1970s and 1980s. One group tended to see teachers as performers who made learning happen and the other tended to see teachers as facilitators who encouraged learning. I will trace each of these belief systems separately.

BELIEF SYSTEM II: TEACHING AS A PERFORMANCE AIMED AT MAKING LEARNING HAPPEN

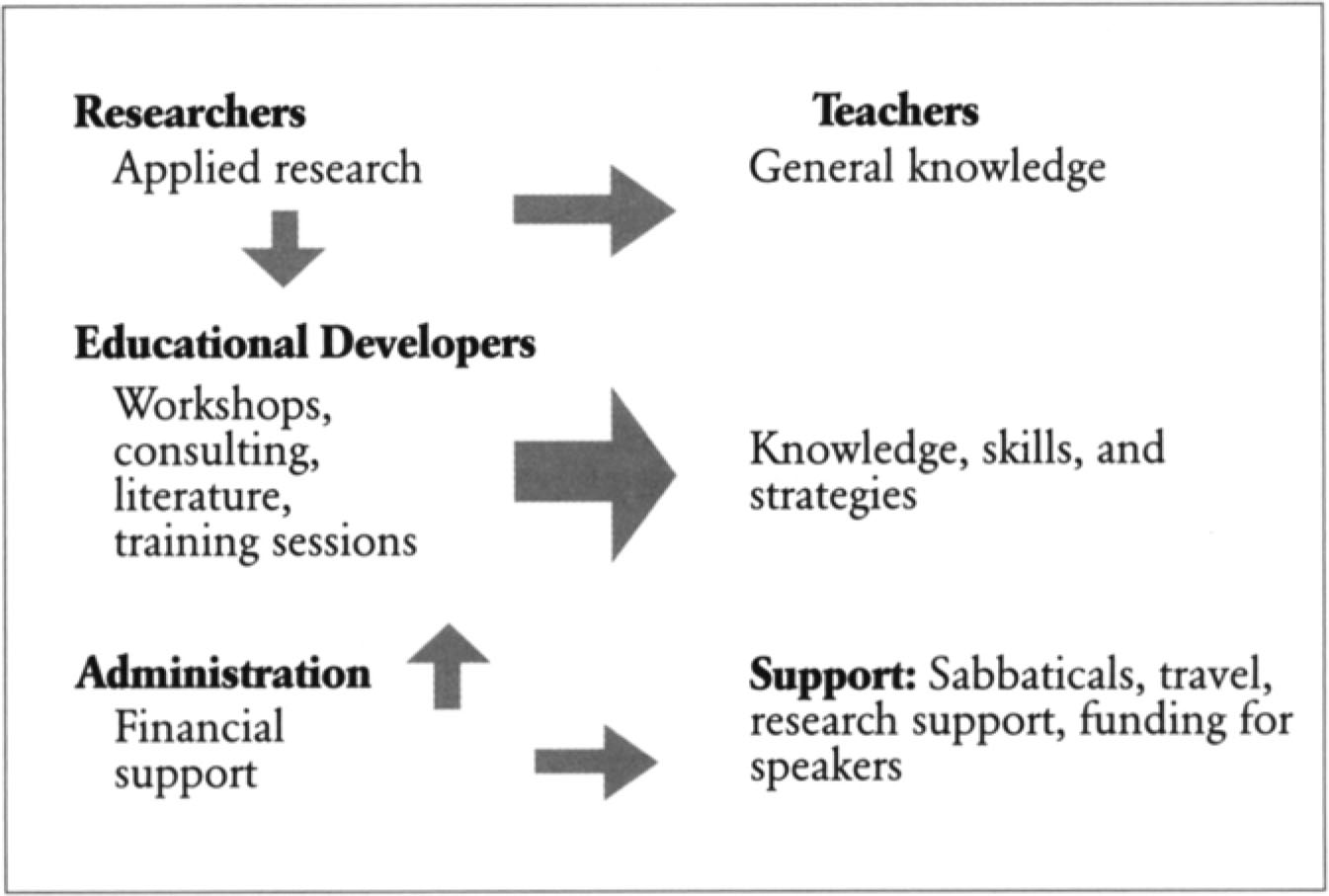

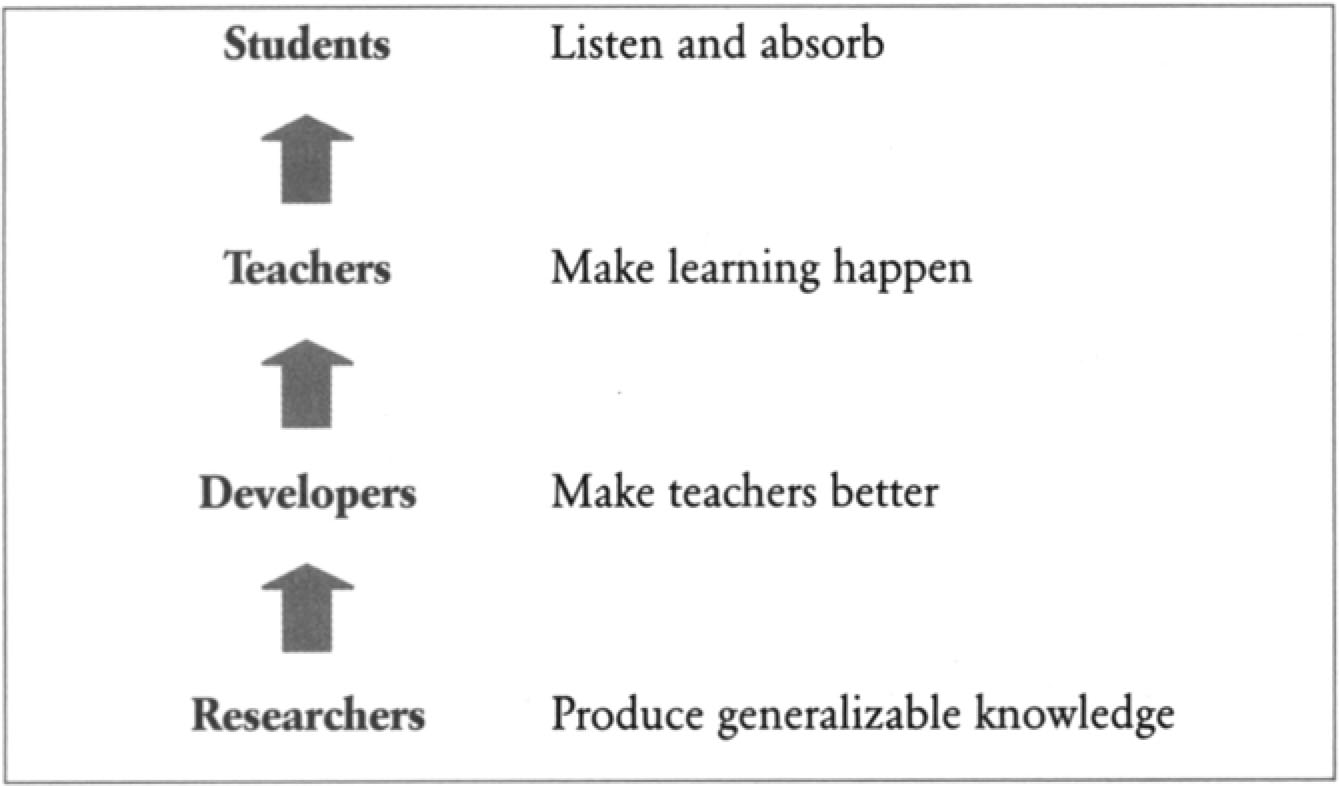

There were precursors to the performance belief system in the late 1950s and early 1960s epitomized by the programmed learning movement. Proponents of programmed learning believed that the modern science of teaching could be captured in the program (Figure 2.2). It would then be “teacher free.”

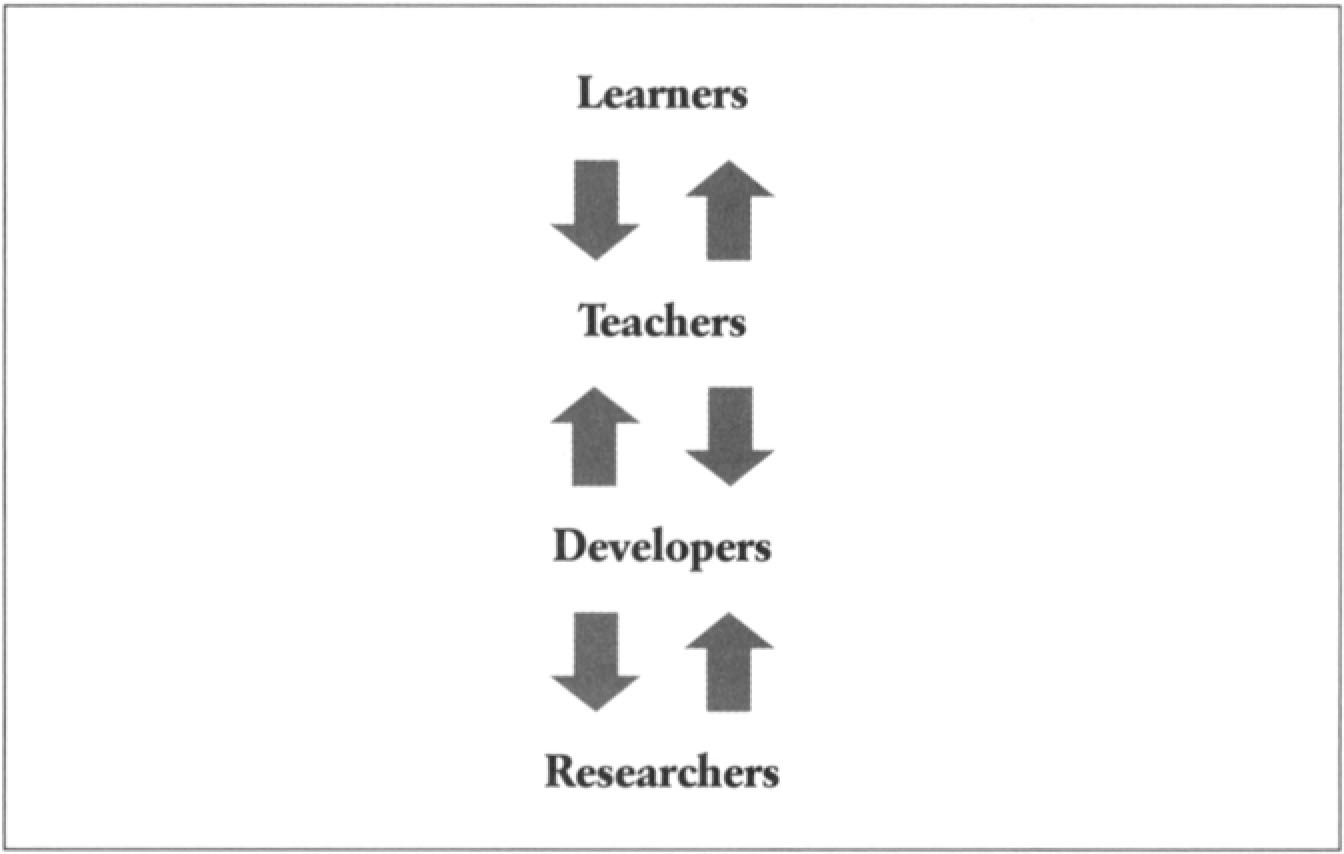

Administrators not only assumed direct responsibility for financial support, but also heavily supported educational development units as well. The units were increasingly staffed by a new group of researchers and practitioners who could translate research for teachers. We called ourselves “developers.” Research was still dominated by the discipline of psychology with its experimental methodology, but researchers who viewed teaching as a skilled performance became more focused on knowledge and skills of teaching rather than on the general principles of teaching. Under the performer belief system, teachers could make learning happen by the application of teaching skills to students. Developers could make professors teach better by training them in the skilled performances. And researchers could suggest and evaluate teaching methods that could be taught as specific skills (Figure 2.3).

This belief system held the teacher responsible, not only for mastery of the field, but also for mastery of the skills of teaching. The teacher could make learning happen (Orme, 1977). The teacher’s relationship with learners was characterized by the metaphors transfer, shaping, and molding. Learners were vessels to be filled, or clay to be molded into shape. Teachers produced an engineer or medical doctor or provided students with principles of biochemistry. Teachers who were guided by these metaphors were likely to blame failure on flaws in the material, for example, or inert or intractable students. If “the container is not very full, the explanation tends to be in terms of leaky containers” (Fox, 1983, p. 152).

If the teacher’s primary role were to transfer information or to shape the student then teachers could focus on the validity of the learning objectives and on the effectiveness of the transmission process. Rather, less attention needed to be paid to the characteristics of individual learners or to the teacher-learner relationships. The teachers’ expectations of their learners would be that learners should be attentive and malleable listeners. The learners’ expectations of their teachers would be that they should be knowledgeable, set clear goals, and use effective communication methods.

Many books on university teaching appeared during this period, a number of them directed at skills, and more faculty were reading them. Some of the more popular ones included Teaching Tips: A Guidebook for the Beginning College Teacher, 6th and 7th editions (Wilbert McKeachie, 1969 & 1978); Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (Ruth Beard, 1970); The Assessment of University Teaching (Barbara Falk & Kwong Lee Dow, 1971); What’s the Use of Lectures? (Donald Bligh, 1972). A number of new journals and societies appeared that were devoted directly to teaching in higher education, including The Chronicle of Higher Education (1966); Jossey-Bass publishers (1967); ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education (1968); Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning (1969); Higher Education (1971); Instructional Science (1972); Research in Higher Education (1973); The Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education (1975); Studies in Higher Education (1976).

I remember clearly the days when my faculty development efforts consisted of attempts to help teachers acquire skilled performances. At one workshop, I used to advise teachers to use movement because research has shown that movement is associated with the best lecturers. My advice did liven up some presentations, but just as often teachers would blindly apply the prescription, jumping all over the place but not helping students learn. Their movements were distracting because they were not choreographed with the point they were making (for example, when I step forward and remove my glasses to make a personal comment).

It is easy to find teachers, even today, who believe that the primary role of the teacher lies in such performances.

A patient-educator from the local diabetic organization, Ms. Drama (not her real name), delivered information about diabetes to a roomful of newly diagnosed patients. Her delivery was excellent. She was witty, dramatic, organized, and had lots of attractive slides to accompany her talk. And the patients said they learned a lot from her session even though she disappeared before any questions were asked and did nothing to establish a relationship with them.

Now imagine that it is the 1980s and you are a university professor who would like to improve your teaching. You could still find help developing useful techniques for delivering lectures or for conducting small groups, just as you did in 1970. The skilled performance approach to teaching is still alive and well. But in 1980 you would also be likely to find developers who would be eager to engage you in exploring your attitudes, intuitions, feelings, sensitivities, and values. Developers might attend to your interaction with your learners. They might offer to help you listen and receive feedback as well as explain and give feedback. They might talk about matching your teaching strategies to student needs.

BELIEF SYSTEM III: TEACHING AS FACILITATION OF LEARNING

In 1980, facilitation of learning was challenging skilled performance for the dominant belief system about teaching. This movement toward sensitivity to students also had very early roots. It began in the late 1940s and early 1950s with Lewinian group dynamics and Rogerian nondirective therapy. It blossomed in the mid-1960s and early 1970s with the NTL training sessions and group dynamics workshops that proliferated during the explosion of faculty development units in the 1960s. In the late 1970s and 1980s, student- and group-centered teaching became very popular.

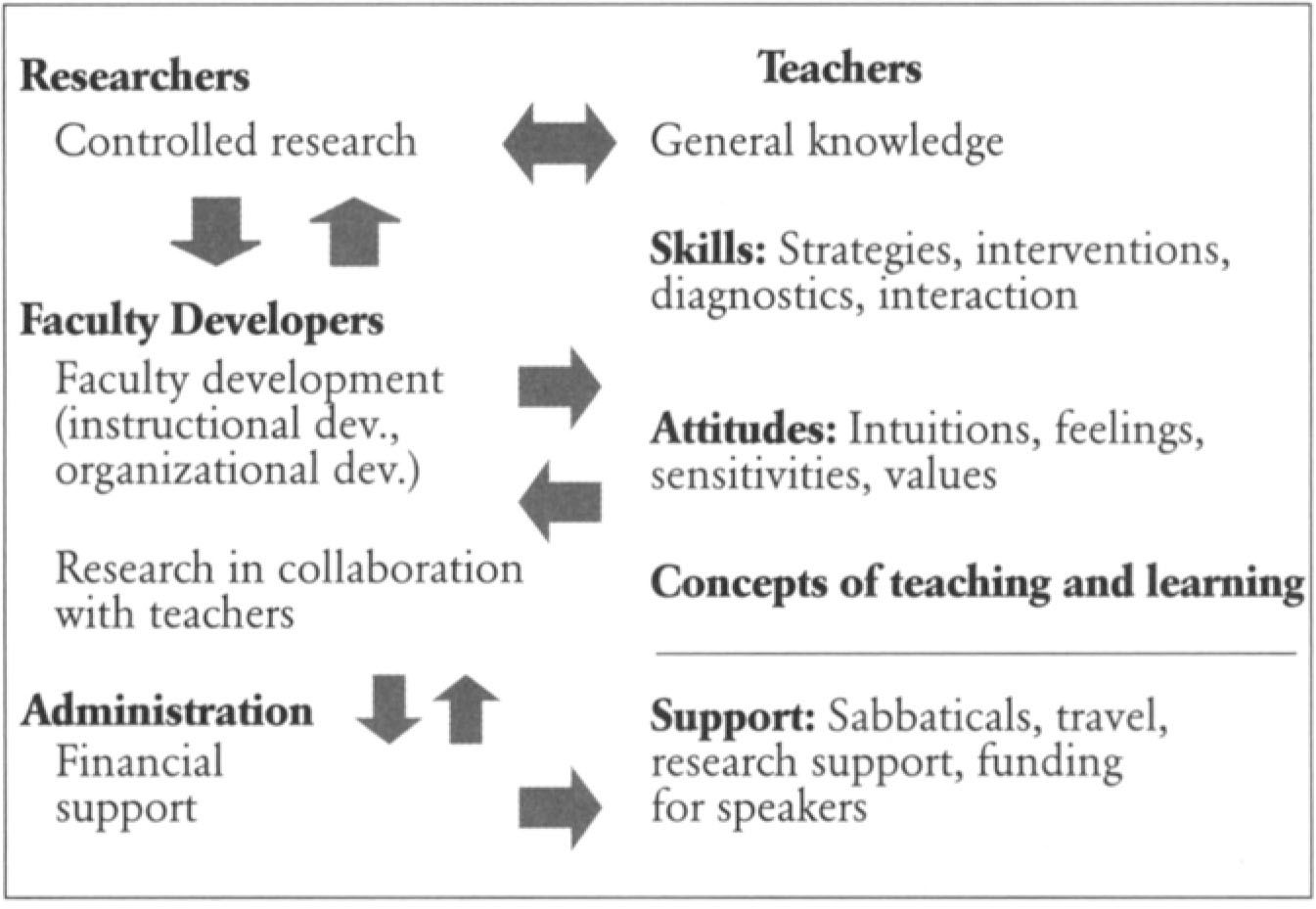

The difference between the two systems can be captured visually by adding two-way arrows to the chart in Figure 2.2. Those who focused on interaction to facilitate learning tended to see their relationships with others as two-way. Developers not only translated research results, they also conducted research and collaborated with researchers. Teachers learned from students too. The teacher was the facilitator of learning whose primary task was to find out about the learner so that interventions could be targeted at specific needs. The teacher needed more than the skills of lecturing, explaining, and providing feedback; the teacher needed the skills of listening, understanding the student, and receiving feedback.

This belief system required a major change in the nature of the teacher’s expertise because it changes the task of teaching from one of static expertise to dynamic expertise. Static tasks require little or no improvisation. A static task involves the performance of a specific set of actions, such as a gymnastics routine, playing a concerto, or surgical knot tying. By contrast, dynamic tasks require the practitioner to decide on appropriate strategies and adapt to various contingencies, such as a hockey game, jazz improvisation, or diagnosing a complicated medical case. Dynamic expertise requires continual feedback and adaptation to new situations. The teacher’s relationship with learners was characterized by interaction and two-way communication (Figures 2.4 & 2.5). Learners, teachers, developers, and researchers all discovered the wisdom of practice–that knowledge can flow two ways and that teachers too can define significant research problems (Schön, 1995).

This third belief system was accelerated by scholarship. The transfer and shaping metaphors of teaching had come under siege. Fox (1983) argued that the growth metaphors (teaching is like gardening) were gradually superceding transfer metaphors (teaching is like filling a mug) as individual teachers developed and the field progressed. Fernstermacher (1986) attacked the assumption that teachers were responsible for student learning. He argued that the teachers’ task is to help students perform the tasks of learning. Indeed, a review of the literature on faculty development concluded that the metaphors of teaching and learning were changing from teaching as transfer of information to teaching and learning as an interaction or conversation (Tiberius, 1986).

Cognitive scientists (e.g., Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Lave, 1988; Vigotsky, 1986) gave us further support for interest in teacher-student interaction. Learning that takes place in the natural setting is more likely to transfer to that setting, including the social setting, the normal interactions between teachers and students.

Constructivism, especially social constructivism, became more popular in this period. Constructivists view learning as a process of enculturation into a community of practice by means of social interaction among learners and between learners and teachers. It follows that the teacher’s role lies in connecting the material to the previous knowledge and experience of the students and to the appropriate social contexts. In order to make these connections, teachers must learn about their learners–their previous experience, motivational orientation, knowledge, and skills. And, since knowledge about learners is gained through interaction, effective teaching is inherently interactive–it is a process of facilitating connections between a subject matter and an active, growing mind. The teacher became “the guide on the side,” not “the sage on the stage.”

My own practice was affected by constructivism. I developed a model of individualized consulting in which the consultant interprets the problem and adjusts the teacher’s methods to the students’ needs. I developed a procedure for improving teaching called “alliances for change.” In this procedure, two teachers act as consultants for one another, each interviews the students of the other teacher and tries to help him or her understand the students better and suggest ways to be more helpful.

It is easy to find contemporary examples of teachers who view their role as one of interacting with students to facilitate learning.

Professor Twoway (not his real name), a teacher of arts and science, engages his students with questions and games. He is knowledgeable, skilled at presenting, and interactive. The students who attended said they learned from him despite what they described as arrogance and condescension. He received no feedback about their view of him.

Finally, let’s assume that you are interested in improving your teaching today. You will still be able to find workshops on teaching performances and on the skills of interaction, but you will also find some new elements. For one, you would be more likely to find help in the area that Karron Lewis (1996) called the personal dimensions of faculty life: career consulting, wellness programs, retirement planning, and stage-of-life. You might also find that developers are interested in your relationship with your students.

BELIEF SYSTEM IV: THE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIP AS A VEHICLE FOR LEARNING

The focus on the relationship had very early roots, in the 1940s with the work of Martin Buber (1947), and is still growing today. In Buber’s educational philosophy, teaching includes a conscious awareness of the teacher-student relationship as a vehicle of teaching. The teachers’ responsibility included helping the learners actualize their potential through personal engagement. Ursula Franklin (1990) argued that focus on relationships is a return to the old apprenticeship system before education became alienated from its social context and became institutionalized. Douglas Robertson (1996) has argued that the need for teachers to learn how to manage the dynamics of helping relationships is particularly important in helping the learner with transformative learning, an intensely emotional kind of learning that requires trust and support.

My colleagues and I are currently providing practice for psychiatry supervisors in relationship skills. We enact a scenario that presents supervisors with a relationship problem and invite the audience to discuss methods of dealing with it. In the “watch scenario,” for example, a staff person expounds on a topic at length while a resident steals a look at her watch. The staff person snaps: “Is there somewhere you’d rather be?” After that brief scenario we invite the audience to speculate as to what is happening and what to do about it.

In my teaching setting there are many examples of clinical teachers who are effective by virtue of their excellent relationships with their students. Yet some of these teachers lack expertise in some areas or the ability to explain clearly.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHERS

My journey into the history of faculty development has convinced me that both teaching and our practice are guided by beliefs about the role of teachers and about the type of relationship between teachers and students. I have identified four belief systems: teacher as content expert, who serves as a resource to the learner, like a book or a picture; teacher as performer, who makes learning happen by transmitting information or shaping students; teacher as facilitator, who encourages learning through interaction with the learner; and teacher as helper, who uses personal engagement and the teacher-learner relationship as a vehicle for learning.

Since these belief systems tend to predispose teachers to particular strategies of teaching, it is tempting to ask whether some belief systems, and thus some strategies, are superior to others in promoting learning. In other words, do these four belief systems form a hierarchy of teacher development? It seems more likely that, under the right conditions, a teacher who holds any of these conceptions of teaching can be effective.

Why is this so? If we accept the assumption that any individual teacher is not the only influence on the learner but is part of a system of influences, then each teacher need only supply a necessary, not a sufficient, ingredient of learning to be considered effective (Bess, 2000). Since the basic ingredients of learning are 1) motivation of some kind, 2) deliberate practice with feedback (or knowledge of results), and 3) options or alternatives, then a successful teacher will supply one or more of these ingredients that are not supplied by other components of the system, such as other teachers, administrators, books, settings, or the learners themselves. A teacher who has the good luck to land in a situation in which he or she is providing just what the learner needs will likely be effective. A teacher who is not so fortunate can improve her or his match with student needs by changing strategies, doing something different. The problem with belief systems is that they tend to reduce flexibility by limiting teachers to particular types of strategies.

Dr. Kontent, the child psychiatry expert who preferred not to teach residents, nevertheless promoted learning because her residents needed the information that she had. The residents also needed feedback but they provided feedback for one another by identifying their own areas of confusion because they were highly motivated, self-directed learners. Residents in this situation also needed help in striking an appropriate relationship with Dr. Kontent. The residency coordinator helped with the following advice: “Observe her and ask questions but do not expect her to clarify your learning needs.”

Ms. Drama, the performer, our patient-educator who delivered information about diabetes but who did not take questions or establish a relationship with her audience, had some content expertise, a highly developed performance, and little appreciation for the interactive and relational roles. Although the patients needed relevant content, Ms. Drama did not interact with the patients to ensure that her content was relevant to the patients. She did not need to. The match was already made by the coordinators of the visit who had previously surveyed and screened the learners, admitting only newly diagnosed diabetics who had a uniform knowledge level. The patients also needed answers to specific questions which Ms. Drama did not provide but the regular ward nurse told the group, prior to her visit: “Jot down any questions that you have and I’ll answer them later. Ms. Drama is a great performer but what she tells you is all she knows. She can’t really answer questions.” The ward nurse also helped create an appropriate relationship with the group by telling the patients: “We are really fortunate to have her coming here.”

Our facilitator, Professor Twoway, engaged his students with questions and games during an interactive lecture, but his extreme anxiety gave him a rigid, haughty appearance in class. In small group interaction with his TAs he established a warm, supportive relationship. The TAs, in turn, helped students to see him in a kinder light.

Our clinical mentors, who are good examples of the fourth role, build alliances–authentic, trusting relationships–with their learners. Such relationships allow mentors to refer their students to colleagues for help in the areas in which they are not expert.

The teachers in these four examples were lucky. Circumstances provided them with a good match between what they offered and what the learner needed. To put it another way, what they could not provide the learner was provided by other components of the system. In contrast, teachers who are ill matched to the learning needs of their students generally get low ratings and need help. One role of the developer may be to arrange the elements of the teaching situation so that such teachers can succeed without changing their belief system. Of course, teachers who possess the conceptual flexibility to move from one belief system to another, to radically change roles not just strategies, as the situation requires, are in a much better position to succeed. Perhaps a second service of the professional developer, then, is helping teachers broaden their conceptions of teaching and learning.

IMPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPERS

Can a developer, who is limited to one of these four belief systems, be effective in helping teachers? Let us take the case of a developer who holds the same belief system about teaching as the client. They are likely to enjoy pleasant interaction that may result in better teaching if they are lucky. Assume that I, as developer, hold a performer model of teaching. Professor Gunnar, the ultimate performer, tells me that he had been sharpening his lecture all weekend. He has a dynamite lecture, targeted perfectly for his students that is going to slay them in the aisles. He asks me, as a teaching consultant, to evaluate his effectiveness. The professor and I can delight in sharing war stories as I reinforce his behavior and arm him with even more powerful techniques for dramatic presentation. If his performances supply what the students need from him, I will succeed in helping him improve his effectiveness.

However, Professor Gunnar’s orientation toward teaching performances may cause him to overlook strategies such as listening to students or building a supportive relationship. And if the latter is the missing ingredient, then I could help him most effectively by finding out what the students think about him and helping him form an alliance with his students, rather than by improving his classroom performance. If I were unable to think beyond the performance role I would be unable to help him.

Second, let us assume that I hold a different model of teaching from that of my client. If I held the facilitator model my reaction to Gunnar might be quite different: “He wants me to do a body count! His militaristic language and the narrowness of his conception of teaching–which invites no input from the students–offend me. He violates my cherished beliefs about the interactive nature of teaching.” I might judge him; focus on what he fails to do rather than what he is doing, to use Bob Kegan’s (1994) analysis. Not a good beginning for a consultant-teacher relationship.

How much better if I were able to see Professor Gunnar’s approach to teaching as emanating from a legitimate belief system about the role of teaching rather than from a sadistic desire to harm. As a developer, I need to keep from feeling threatened, personally violated, when my definition of teaching is challenged. To do this, I need to mentally step away from my own values and definitions (Kegan, 1994). Kegan’s (1994) research indicates that only at this level of consciousness are people able stand apart from such belief systems as I have outlined here, to see them as “out there,” as “objects,” rather than as part of oneself. Moreover, this ability is not a discrete skill that we developers can learn at a POD workshop. It requires an evolution of consciousness, a gradual developmental process. And only about half the population has reached this level.

I am fairly certain that I have this ability to stand apart from and avoid being completely identified with any one of the four belief systems about teaching. The resulting flexibility enables me to arrange teaching contexts in which teachers can make effective contributions to learning even if their view of teaching is more limited. I confess that thinking about this evokes a warm feeling of professional competence, a rare treat for developers, as if I am living in a three-dimensional world helping flat-landers negotiate their two-dimensional spaces. But what happens when I encounter Professor Post Modern who functions at Kegan’s next level of consciousness? I’ll tell you. Professor P. M. heard my lecture at POD and, although she understood what I meant by these different roles, she saw them as different modes of herself manifested in different contexts. Most of the time, she said, her teaching embodies all of these roles.

How do I help Professor P. M. when my best practice consists of adjusting relatively durable elements of the system so that my client can be an effective contributor? What is my role in helping a teacher who is not a durable element? It’s nuclear, as the surfers say. As I write this I feel the familiar strain that attends growth mixed with anxiety about my role as a developer in a postmodern world. At present I can see postmodernism with peripheral vision only. When I look at it directly it disappears, like a very dim light.

REFERENCES

- Australian Vice Chancellors’ Committee. (1963). Teaching methods in Australian universities (Report). Melbourne, Australia: UNSW Press.

- Beard, R. M. (1970). Teaching and learning in higher education. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin.

- Bess, J., & Associates. (2000). Teaching alone, teaching together: Transforming the structure of teams for teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bligh, D. (1972). What’s the use of lectures? (3rd ed.). Hertfordshire, England: Penguin.

- Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 13, 32-41.

- Buber, M. (1947). Between man and man. London, England: Collins.

- Buxton, C. (1956). College teaching: A psychologist’s view. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace.

- Centra, J. A. (1976). Faculty development practices in U.S. colleges and universities. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

- Cooper, R. (1958). The two ends of the log: Learning and teaching in today’s college. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Falk, B., & Dow, K. L. (1971). The assessment of university teaching. London, England: Society for Research into Higher Education.

- Fernstermacher, G. D. (1986). Philosophy of research on teaching: Three aspects. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed.) (pp. 37-49). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Fox, D. (1983). Personal theories of teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 8 (2), 151-163.

- Franklin, U. (1990). The real world of technology. Toronto, Canada: CBC Enterprises.

- Gaff, J. G. (1975). Toward faculty renewal: Advances in faculty, instructional, and organizational development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Gage, N. L. (Ed.). (1963). Handbook of research on teaching. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

- Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lave, J. (1988). Cognition and practice: Mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, K. G. (1996). Faculty development in the United States: A brief history. The International Journal of Academic Development, 1 (2), 26-33.

- Many, W. A., Ellis, J. R., & Abrams, P. (1969, Spring). In-service education in American senior colleges and universities: A status report. Illinois School Research, 46-51.

- McKeachie, W. J. (1951). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

- McKeachie, W. J. (1969). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher (7th ed.). Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

- McKeachie, W. J. (1978). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher (8th ed.). Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

- Miles, M. B. (1959). Learning to work in groups: A program guide for educational leaders. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Orme, M. (1977). Effective teaching techniques (video). Toronto, Canada: Ryerson TV Studios.

- Pratt, D. D., & Associates. (1998). Five perspectives on teaching in adult and higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

- Robertson, D. L. (1996). Facilitating transformative learning: Attending to the dynamics of the educational helping relationship. Adult Education Quarterly, 47(1), 43-53.

- Schön, D. A. (1995, November/December). The new scholarship requires a new epistemology. Change, 27-34.

- Sullivan, L. L. (1983). Faculty development: A movement on the brink. College Board Review, 127, 20-21, 29-31.

- Tiberius, R. G. (1986). Metaphors underlying the improvement of teaching and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 17 (2), 144-156.

- Vigotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Contact:

Richard Tiberius

University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine

Centre For Research in Education at the University Health Network

200 Elizabeth Street, 1 ES 583

Toronto, Ontario, M5G 2C4, CANADA

(416) 340-4194

(416) 340-3792 (Fax)

Email: r.tiberius@utoronto.ca

or

Department of Psychiatry

University of Toronto

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Clarke Division, 8th floor, Room 826, 250 College Street

Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1R8, CANADA

Richard Tiberius is at the Centre for Research in Education in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto, Canada, and is Professor of Psychiatry. His main roles include collaboration with health science faculty on educational research projects, supervision of resident research, and various faculty development activities. He teaches graduate courses in research methods and educational development at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.