5 Faculty Learning Communities: Change Agents for Transforming Institutions into Learning Organizations

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In my 20 years of faculty development, I have found faculty learning communities to be the most effective programs for achieving faculty learning and development. In addition, these communities build communication across disciplines, increase faculty interest in teaching and learning, initiate excursions into the scholarship of teaching, and foster civic responsibility. They provide a multifaceted, flexible, and holistic approach to faculty development. They change individuals, and, over time, they change institutional culture. Faculty learning communities and their “graduates” are change agents who can enable an institution to become a learning organization. In this article I introduce faculty learning communities and discuss ways that they can transform our colleges and universities.

In higher education, this is a time of increasing interest in learning communities. Palmer (1998) searches for “an image of teaching that has challenged me for years, one that has an essential but seldom-named form of community at its core: to teach is to create a space in which the community of truth is practiced” (p. 90). Cross (1998) addresses the question, “Why Learning Communities? Why Now?” She gives three reasons: “philosophical (because learning communities fit into a changing philosophy of knowledge), research based (because learning communities fit with what research tells us about learning), and pragmatic (because learning communities work)” (p. 4). Learning communities also play an important role in helping individuals and institutions experience a structure that is part of the learning paradigm (Barr & Tagg, 1995; Barr, 1998). Furthermore, Shapiro and Levine (1999) observe that “When campuses begin to implement learning communities, whether they know it or not they are embarking on a road that leads to a profound change in culture” (front cover).

Students who have participated in learning communities develop an educational citizenship, “an understanding of the nature and importance of mutual interdependence in shared learning endeavors” (Tinto, 1995, p. 12). Tinto also reports that students “learned more, found academic and social support for their learning among their peers, and they became actively involved in their learning” (p. 12). Learning communities give students a sense of belonging; thus, they persist rather than retreat. These students “made a significant and unusual leap in intellectual development during their learning community experience” (Gabelnick, MacGregor, Matthews, & Smith, 1990, p. 66). According to Perry (1970), “once students embrace complexity and begin to build the habits and skills of making meaning within that complexity, there is no turning back” (pp. 107-108, as quoted in Gablenick et al., 1990, p. 71).

Although the above comments are about student learning communities, they are also true for faculty learning communities. Faculty are students when they are members of a faculty learning community—an active, collaborative, year-long learning environment. Fulton and Licklider (1998) claim that “New visions of professional development suggest that the practices needed to support faculty learning are analogous to those needed to support student learning” (p. 55). It is no surprise, then, that learning and development outcomes for faculty in learning communities are similar to those for students who are members of student learning communities.

Thus, faculty who are graduates of faculty learning communities have a perspective that goes beyond their disciplines and includes a broader view of their institution and higher education. With respect to intellectual development in this arena, participants may move through multiplicity, interested in and trying many new approaches to teaching, to relativity (Perry, 1970), assessing various approaches against their learning objectives, and applying the scholarship of teaching. They, too, embrace and make meaning within the complexity of teaching and learning beyond their disciplines. They are likely to take responsibility for involvement in setting institutional goals, pursuing difficult campus issues, and contributing to the common good. And they persist in their efforts because they belong to a community of support.

LEARNING COMMUNITIES

Student Learning Communities

In the 1920s and ’30s, Alexander Meiklejohn and John Dewey developed the concept of a student learning community in higher education. Increasing specialization and fragmentation caused Meiklejohn (1932) to call for a community of study and a unity and coherence of curriculum across disciplines. Dewey (1933) advocated learning that was active, student centered, and involved shared inquiry. A combination of these approaches generated a few promising but short-lived programs, for example, at the University of California, Berkeley (Tussman, 1969). However, after success with student learning communities at The Evergreen State College in the 1970s (Jones, 1981), several institutions initiated learning communities that have produced a pedagogy and structure that has led, among other things, to students’ increased grade point averages and retention (Gabelnick et al., 1990). Learning community models include linked courses, clusters, freshman interest groups, federated learning communities, and coordinated studies. These structures vary in complexity from linked courses, in which a cohort of students enrolls in two courses and the degree of faculty cooperation varies, to coordinated studies, in which a cohort of students and faculty participate in a multidisciplinary program taught in block mode around a central theme (Gabelnick et al., 1990). The term learning community traditionally has been applied to programs that involve first- and second-year undergraduates, along with faculty who design the curriculum and teach the courses. I call these student learning communities, although “The modeling, mentoring, and learning in this situation are invaluable in faculty development” (Gabelnick et al., 1990, p. 80).

Faculty Learning Communities

I define a faculty learning community to be a cross-disciplinary faculty group of eight to 14 members engaged in a year-long program with a curriculum about enhancing teaching and learning and with frequent seminars and activities that provide learning, development, and community building. In the literature about student learning communities, the word student usually can be replaced by faculty and still make the same point; for example, “As students develop ownership of ‘their’ learning community, a sort of civic pride arises and students want to do well” (Gabelnick et al., 1990, p. 59). I have found that faculty develop a similar civic pride, for example, as each faculty community prepares and delivers its annual campus-wide seminar on participants’ individual and joint innovations in teaching and learning (Cox, 1999b).

The term faculty learning community is new, although a few such faculty development programs have been around since the mid-1970s, for example, the Lilly Endowment’s Post-Doctoral Teaching Fellows Program that enabled small communities of junior faculty to include a focus on teaching during one of their pretenure years (Austin, 1992). However, faculty learning communities have been overlooked as an effective avenue for faculty development. For example, Kurfiss and Boice (1990) surveyed members of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education (POD) to determine existing and desired faculty development practices. The faculty learning community approach was not included in the 26 practices reported, although 18 of the 26 are involved in faculty learning community activities. Wright and O’Neil (1995) surveyed key instructional role players at institutions in the US, Canada, the UK, and Australia to determine the potential of 36 faculty development practices that could improve teaching on their campuses. Again, faculty learning communities or their equivalent are not included on this list, although 30 of the 36 practices take place in, or are connected to, communities. This data suggests the absence of a holistic, connected approach to faculty development.

Examples of Faculty Learning Communities

For over 20 years, we have been designing and directing faculty learning communities at Miami University, a state-supported Doctoral I institution with 14,500 undergraduates, 1500 graduate students, and 750 full time faculty on the Oxford campus, plus two regional, urban, commuter campuses, each with 2000 students and 50 faculty. I define two types of faculty learning communities: cohort-focused and issue-focused. I have developed and worked with two or more examples of each type, which are components of Miami’s teaching effectiveness programs. In addition to faculty learning communities, these programs include a wide variety of teaching grants that support the development of teaching innovations by individuals and departments, plus the usual assortment of faculty development activities such as campus workshops, consultations, and new faculty orientation. These programs are funded by contributions from Miami alumni.

Cohort-focused communities. Cohort-focused faculty learning communities address the teaching, learning, and developmental needs of an important cohort of faculty that has been particularly affected by the isolation, fragmentation, or chilly climate in the academy. The curriculum of this year-long community is shaped by the participants to include a broad range of teaching and learning areas and topics of interest to them. Two examples of cohort-focused communities at Miami are the Teaching Scholars Community for junior faculty (Cox, 1995), in place for 22 years, and the Senior Faculty Community for Teaching Excellence for mid-career and senior faculty (Cox & Blaisdell, 1995), in place for 10 years.

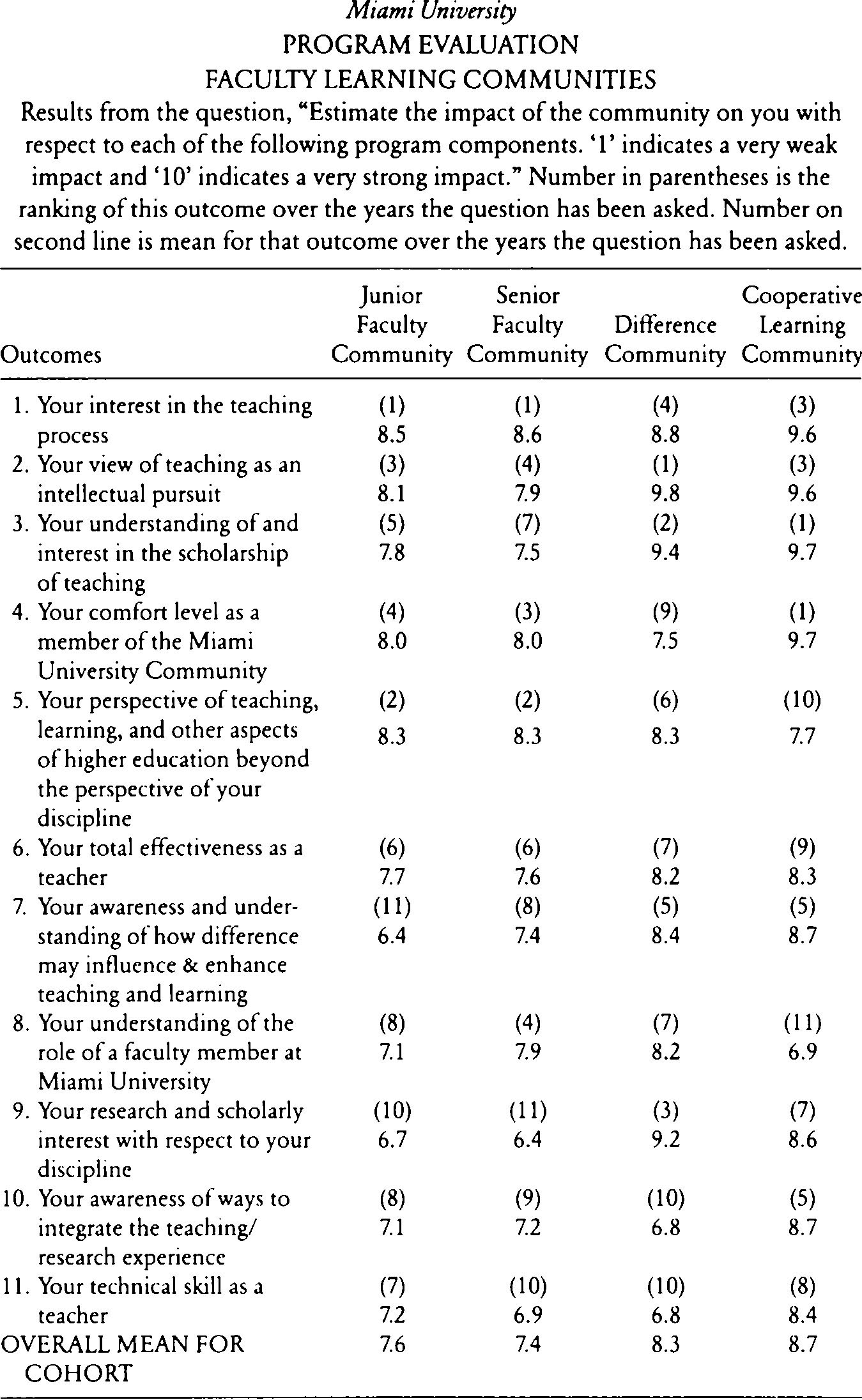

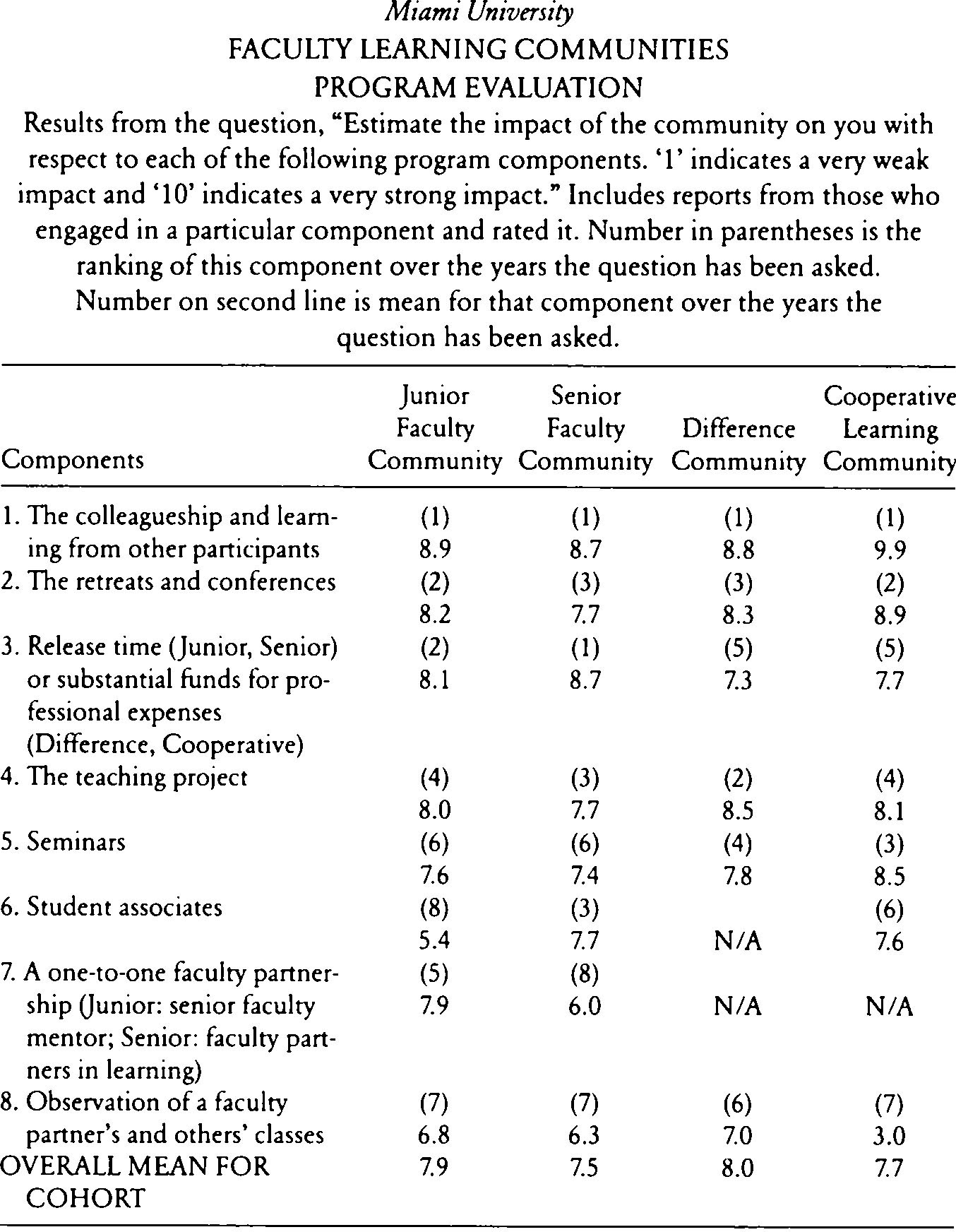

The junior faculty community provides a safe place for pretenure folks in their second through fifth years to meet and work on teaching opportunities with peers from other disciplines. Most participants develop into quick starters (Boice, 1992). The outcomes noted in Figure 5.1 indicate that they also become very interested in the teaching process and gain a perspective of teaching, learning, and higher education beyond their disciplines. They become comfortable in the university community, overcoming the great stress often felt by junior faculty (Sorcinelli, 1992). Figure 5.2 shows that the faculty partner—an experienced faculty mentor—has a strong impact on the development of junior faculty members (Cox, 1997). At Miami, participants are tenured at a significantly higher rate than junior faculty who do not participate in this community (Cox, 1995). Junior faculty communities will make a positive impact on the culture of an institution over the years if given multi-year support (Cox, 1995; List, 1997).

The senior faculty community offers participants time, safety, funds, and colleagueship across different disciplines in order to reflect on past teaching and life experiences and investigate and chart new directions. Figure 5.2 indicates that this community values most the colleagueship and learning from the other participants, the release time of one course for one semester for the year, and the retreats and conferences. Figure 5.1 reports outcomes similar to those for junior faculty community members. The senior community fulfills many of Karpiak’s (1997) recommendations of what the university administration should do for professors at midlife: provide opportunities for them to be members of a team, to help each other grow as intellectuals, to develop support networks, and to counsel each other on career matters. The institution is humanized through the recognition and support of the different contributions that these experienced professors bring.

These two cohort-focused communities provide faculty development that prepares “staff at each stage of their career so they take on new roles and responsibilities” (Brew & Boud, 1996, p. 20).

Figure 5.1 RATINGS OF COMMON PROGRAM OUTCOMESOther items specific to a particular community were also rated; they are available from the author.

Figure 5.1 RATINGS OF COMMON PROGRAM OUTCOMESOther items specific to a particular community were also rated; they are available from the author. Figure 5.2 RATINGS OF COMMON PROGRAM COMPONENTSOther items specific to a particular community were also rated; they are available from the author.

Figure 5.2 RATINGS OF COMMON PROGRAM COMPONENTSOther items specific to a particular community were also rated; they are available from the author.Issue-focused communities. Each issue-focused learning community has a curriculum designed to address a special campus teaching and learning issue, for example, diversity, cooperative learning, or development of teaching portfolios. These communities offer membership to a variety of faculty ranks and cohorts, but with a focus on a particular theme. A particular issue-focused faculty learning community is no longer offered when the campus-wide teaching opportunity or issue of concern has been satisfactorily addressed. Three examples of issue-focused communities at Miami are the Faculty Community Using Difference to Enhance Teaching and Learning, in place for three years (Stevens & Cox, 1999); the Community Using Cooperative Learning to Enhance Teaching and Learning (Cox, 1999a), in place for one year; and the Teaching Portfolio Project (Cox, 1996), in place from 1993-1996.

We created the Faculty Community Using Difference to Enhance Teaching and Learning in order to involve faculty in addressing serious diversity issues on campus. The strategy hinged on the belief that if faculty could connect diversity issues with ways to increase the learning of their students, instructors would get involved. The safety offered by this faculty learning community has been important in opening a constructive dialogue and fostering risk taking. “Learning communities have features that feminist literature suggests are important, such as cooperation and shared power, development of a personal connection to the material being studied, and emphasis on the affective aspects of learning” (Gabelnick et al., 1990, p. 79). Figure 5.1 notes that members in this community have a level of comfort in the university community below those in other groups. This is a result of concerns raised by their investigations about their campus climate. They rate highly the impact of pedagogical scholarship and their view of teaching as an intellectual pursuit. This is a result of their readings, seminars, and conversations.

The teaching portfolio project was developed to meet faculty interest in investigating and constructing teaching portfolios. Rather than take a campus-wide approach, we chose to let participating departments design and develop uses and procedures particular to their disciplinary and departmental cultures. The teaching portfolio project involved communities at two levels. First, a learning community team was formed by each participating department, with membership across departmental subdisciplines, ranks, and interests. The learning community at the campus-wide level was made up of the faculty who coordinated the communities in their departments or divisions. This community of team coordinators provided an invaluable support group with which to share ideas, frustrations, and successes (Cox, 1996).

The Faculty Community Using Cooperative Learning to Enhance Teaching and Learning provides a safe place for faculty who wish to try this aspect of active learning. According to Millis (1990), “Faculty developers can speed the dissemination process by helping faculty understand a) the nature of cooperative learning; b) its documented, well-researched impact on student achievement, self-esteem, social skills, and interracial harmony; and c) its liberating effects on college-level teaching and learning” (p. 44). A faculty learning community provides an excellent place to accomplish these goals. This community also rates highly the impact of the scholarship of teaching (Figure 5.1). In sharp contrast to the Difference Community, this group is comfortable in the university community.

New issue-focused faculty communities under consideration for 2000-01 include ones on technology, problem-based learning, servicelearning, team teaching, and student learning communities.

ASPECTS OF FACULTY COMMUNITIES

The following items are common to all of the faculty learning communities described above.

Long-Term Goals

The long-term goals of faculty learning communities for the university are to

build university-wide community through teaching and learning

increase faculty interest in undergraduate teaching and learning

nourish the scholarship of teaching and its application to student learning

broaden the evaluation of teaching and the assessment of learning

increase faculty collaboration across disciplines

encourage reflection about general education and coherence of learning across disciplines

create an awareness of the complexity of teaching and learning increase the rewards for and prestige of excellent teaching

increase financial support for teaching and learning initiatives

investigate and incorporate ways that difference can enhance teaching and learning.

Each faculty learning community has its own additional specific objectives (Cox, 1999a). For example, an objective of the Junior Faculty Community is the development of syllabi that articulate clear learning objectives, and an objective of the Community Using Difference is to increase the use of pedagogies and behaviors that create inclusive classroom cultures.

Activities

According to Fulton and Licklider, “Faculty, like their students, learn by reading, experiencing, reflecting, and collaborating with others” (1998, p. 55). Each year the activities for these communities vary somewhat but are likely to include the following.

Biweekly seminars on teaching and learning. Seminars in a faculty learning community go “beyond the individual ponderings of good teachers to a community of conversation where teachers cannot only express their conceptions of teaching in discussion and reflection with others, but go beyond mere technical elements or classroom practice to the richer dimensions of human understanding” (Harper, 1996, p. 263). Recent topics include assessing student learning, enhancing the teaching/learning experience through awareness of developmental stages (for example, student intellectual development or the inclusiveness of one’s course curriculum), sharing student and faculty views of teaching and learning (the community members and their student associates meet) (Cox & Sorenson, 1999), and having all participants of a community read topics selected from articles or books (See Appendix 5.1). Some seminars are led by guest faculty; others are conducted by the participants themselves. In the second semester, individuals or the group present a seminar to the entire campus. As on other campuses, this reading group facet of a community has contributed to campus organizational and curriculum change (Eckel, Kezar, & Lieberman, 1999), for example, on the Cox campus, the establishment of a liberal education program. Communities of conversation are established in faculty learning communities because these communities are not evaluatory, trust and respect is established, and participants are open to the concerns of the others (Harper, 1996).

National conferences and retreats. Retreats and conferences provide a developmental approach that unfolds chronologically to enable

introduction of new members to the community culture and its expectations

bonding

learning from nationally recognized teacher scholars

learning from the other community members

learning about national issues and polices in higher education beyond one’s discipline

the opportunity to present a paper on teaching and learning

passing the torch to new members

An opening/closing retreat is held in May, with the graduating members of the community sharing information and experiences with the new participants about various aspects of the program, such as helpful seminar topics, faculty partner and student associate selection, teaching projects, and national conferences. In the early fall, a bonding retreat occurs at another campus or national teaching conference; it is also the setting for seminars with faculty from other universities. In late fall, each community participates in the annual Lilly Conference on College Teaching at Miami University, a meeting of nationally known teacher-scholars and faculty from other campuses. During the second semester, each group attends a national conference on higher education, such as Lilly-West or American Association of Colleges and Universities. Members are encouraged to make presentations at the Lilly conferences. Our office pays all travel expenses.

Teaching projects. Members of all communities individually pursue self-designed learning programs, including a teaching project, for which they receive financial support. Past projects have included developing expertise and courseware for computer-assisted instruction, redesigning an ongoing course for distance learning, and investigating, learning, and trying a new teaching method. Most of these projects are shared with the university at a campus-wide seminar.

Faculty partners. Each community member selects a colleague to work with during the year. In the case of junior faculty, the person is an experienced faculty member from outside that community who serves as a mentor. Senior faculty community members pair up with someone inside that community, as in the New Jersey Partners in Learning model (Katz & Henry, 1993).

Student associates. Each participant selects one or two students who provide perspectives for that participant’s teaching and learning project, as well as about seminar topics discussed in that community. Strategies for student selection, engagement, and rewards are provided in Cox and Sorenson (1999).

The Scholarship of Teaching

Each community engages in a sequence of activities designed to introduce its members to a discipline that is new to most of them: the scholarship of teaching. Our faculty development office has an extensive library and subscribes to the few newsletters and multidisciplinary journals that publish the scholarship of teaching. Seminars early in the program address topics from the community’s focus book (Appendix 5.1) or articles that provide introductions to key topics such as student intellectual development (Thomas, 1992; Kloss, 1994). As members begin their teaching project, they are expected to place it in context (Richlin, in press). We encourage projects that are relatively straightforward, perhaps involving classroom assessment techniques (Angelo & Cross, 1993) and classroom research (Cross & Steadman, 1996). This requires reading the appropriate scholarship of teaching. Participants share their project development with each other during the first semester. In the latter part of the second semester, they present their projects to the campus, including handouts with references. At first some feel uncomfortable with this. They react with surprise to the possibility of becoming an expert in a new discipline so quickly—after all, it took them years to master their disciplines. However, except for junior faculty, these are seasoned practitioners of teaching. Once the participants—even the junior faculty—become familiar with the scholarship of teaching needed for their projects, gain support from their community, and experience the helpful perspectives of the multidisciplinary audience to whom they present, they become interested partners in the scholarship of teaching.

Compensation and Rewards

Participation in a faculty learning community takes a lot of time and work: attendance at weekend retreats, national conferences, and biweekly seminars; interaction with a student associate and a faculty partner; reading the new literature of the scholarship of teaching; development of and work on a teaching project; and preparation of a seminar presentation for the campus and, perhaps, a national conference.

We have two ways of compensating faculty participants. First, and best, is to provide release time from one course for one semester. This is done at the rate for adjuncts. If a department chair can create the release time in another manner, then the department receives the funds and usually allocates them to the faculty member, for example, to purchase technology or international travel. This compensation is available only in the cohort-focused communities. Also, each member receives funds to enable his or her learning plan or teaching project. Junior faculty participants each have $125 available, and senior faculty have $500.

Unfortunately, we do not have the budget to provide release time for members of the issue-focused communities. There, each participant receives an honorarium to use for professional expenses. Members of the Community Using Difference each receive $1500, and members of the Cooperative Learning Community receive $1000. In the teaching portfolio project, each participating department received $5000.

Each community coordinator receives one course release time for both semesters plus the honorarium available for his or her particular community. Service as a coordinator must be approved by his or her department chair.

Applications for Community Membership

Before applying for membership in a faculty learning community, faculty must obtain approval from their chair, dean, and, if applicable, their regional campus executive director. Chairs are encouraged to write a letter of support. Applications for participation in the next year’s community are due in late March.

Requests for information that are common to the application forms for each community are as follows:

Briefly describe the nature of your current teaching responsibilities. Include the learning objectives from one of your courses as stated in your syllabus.

Describe innovative teaching activities in which you have been involved (efforts to improve teaching, development of curricular materials, etc.).

Indicate two or three of your most pressing needs regarding teaching and learning.

Describe your reasons for wanting to participate in this community.

Part of this program is an individual teaching project pursued by each participant. At this time, what area of interest do you wish to pursue? Of course, this may change as you engage your community.

This community involves working with a faculty partner and student associate of your choice. Although you need not have particular persons in mind at this time, in what ways would you take advantage of this opportunity, and how do you see this aspect of the program as being helpful to you?

What do you think you can contribute to this community (for example, particular teaching experience)?

Briefly state your philosophy of teaching.

Selection Procedure and Criteria

Different subcommittees of Miami’s Committee for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching (CELT) select the membership of each community. Each subcommittee is chaired by the coordinator of that community, and members include former community participants, a student associate, and a member of CELT who has not been a part of the community. Selections for the new year are recommended to the provost. New participants are announced in mid-April.

The selection criteria used to evaluate applications are commitment to quality teaching, level of interest in the community, need, openness to new ideas, potential for contributions to the community, and plans for use of the award year. Participants are chosen to create a diverse group representing a variety of disciplines, experiences, and needs.

Assessment

Participants of all communities agree to prepare mid-year and final reports indicating the impact of the community on outcomes related to program goals and objectives (Figure 5.1) and the impact of the various components of the community on their teaching and learning (Figure 5.2). The results of this assessment relative to the objectives particular to a certain community and not common to all communities are reported elsewhere in the literature (for junior faculty, in Cox, 1995, for senior faculty, in Cox & Blaisdell, 1995, and for the Community Using Difference, in Stevens & Cox, 1999). In an open-ended section of the report, each participant also details the results and status of his or her teaching project and interaction with faculty partner and student associate.

The selection subcommittee for a community reviews the mid-year and final reports and serves in an advisory role to the coordinator of the community.

Leadership

As we form new communities, we select as coordinators former faculty participants who have been exemplary members in one or more of the communities. They are usually successful seminar presenters or members of past junior faculty groups who have later served as mentors. Some have led effectively as committee chairs of CELT. All exhibit a talent for and interest in faculty development and have experience in the topic of the community they lead. Among faculty, they are positive opinion leaders (Middendorf, 1999). However, contrary to Middendorf’s recommendations, we do not involve them sparingly. Instead, these coordinators make generous commitments of time and effort to their communities. They also share the results of their communities locally and nationally; all have presented at national faculty development or teaching conferences. Thus, each community coordinator makes a civic contribution to the common good of students, faculty, the university, and teaching and learning.

Recommendations for Start-Up

An overview of the aspects of and recommendations for initiating and continuing faculty learning communities is in Cox (1999). Materials for practice in each community are in Cox, Cottell, & Stevens (1999). I recommend that developers begin with just one community in order to gain experience, fit the community approach into their campus culture, and build support by providing assessment results. When administrators are given choices, they tend to invest first in faculty development for junior faculty and in diversity or technology issues; these may be the best places to start on the campus. For more detailed recommendations for starting a junior faculty community, see Cox (1995, 1997).

Overcoming Obstacles

Some obstacles must be addressed in order to start and continue faculty learning communities. One obstacle is the length of time needed for an institution to show a cultural change as a result of the community approach—at least five years. Other obstacles include cost, participants’ time commitment, and the isolated nature of faculty life—the group structure of the community experience is not for everyone. These obstacles are similar to some of those that challenge student learning communities, as Barr (1998) observes: “Faculty experimenting with learning communities are finding themselves hard-pressed to keep them going” (p. 22).

The annual cost for each community of eight to ten members plus coordinator varies from $20,000 to $30,000. The top expense items are release time (or honorarium) and travel. However, providing first-class treatment for participants earns their generous time commitment, appreciation, and support.

Communities do not appeal to everyone. For example, an excellent teacher, who had served successfully as a mentor in our junior faculty community and also followed a colleague’s participation in the senior faculty community, approached me with an enthusiastic suggestion: Perhaps just one meeting of a community at the start of the year would suffice, enabling full concentration on one’s individual teaching project the rest of the year. Another faculty member suggested that we bring in an expert at the start and avoid the amateurish discussions of the group. With this in mind, developers initiating communities should continue other support for individuals: grants, consultations, and “one-time-only” seminars.

Nevertheless, once one successful faculty learning community is up and running, and barring an unexpected university-wide budget shortfall, the positive outcomes for participants and the institution should convince administrators to continue and expand funding. Enthusiastic participants will convince reticent colleagues to join.

If the developers’ campus looks favorably upon the outcomes of student learning communities, then they can argue that faculty learning communities can produce similar outcomes for faculty.

The Role of Faculty Developer

Faculty developers play a key role in managing the operations of faculty learning communities. As part of my role as director of teaching effectiveness programs, I coordinate the junior faculty community and oversee the other three. This consists of working closely with each faculty coordinator. Our office handles room scheduling, meals, travel, publicity, and budget items.

As developers within our institutions, “we need to promote an understanding of the process of faculty development over time, leading to a full integration of the fragments of academic work” (Kreber & Cranton, 1999, p. 225). Providing a variety of faculty learning communities over the years enables faculty to concentrate on specific issues or developmental needs at various times during their careers.

FACULTY LEARNING COMMUNITIES AS CHANGE AGENTS

Including faculty learning communities in your institution’s repertoire of faculty development practices answers the need for more holistic, connected, and flexible approaches to faculty development and thoughtful institutional change. Faculty learning communities answer the question posed by Hubbard, Atkins, & Brinko (1998): “how to address the larger issue of institutional, professional, and personal change as a whole, interrelational and interacting, multifaceted system” (p. 39). Faculty learning communities address the paradigm shift in educational development and institutional change in the manner Chism (1998) encourages, by incorporating faculty study and the redress of “hitches” in the system: “As educational developers, we are also in an ideal situation to create communities of inquiry related to the changes that could be made: for example, a special interest group exploring multicultural teaching or service learning” (p. 143). Issue-focused faculty learning communities are just such an example, providing a way to embrace hitches in order to accomplish change.

Becoming a Learning Organization

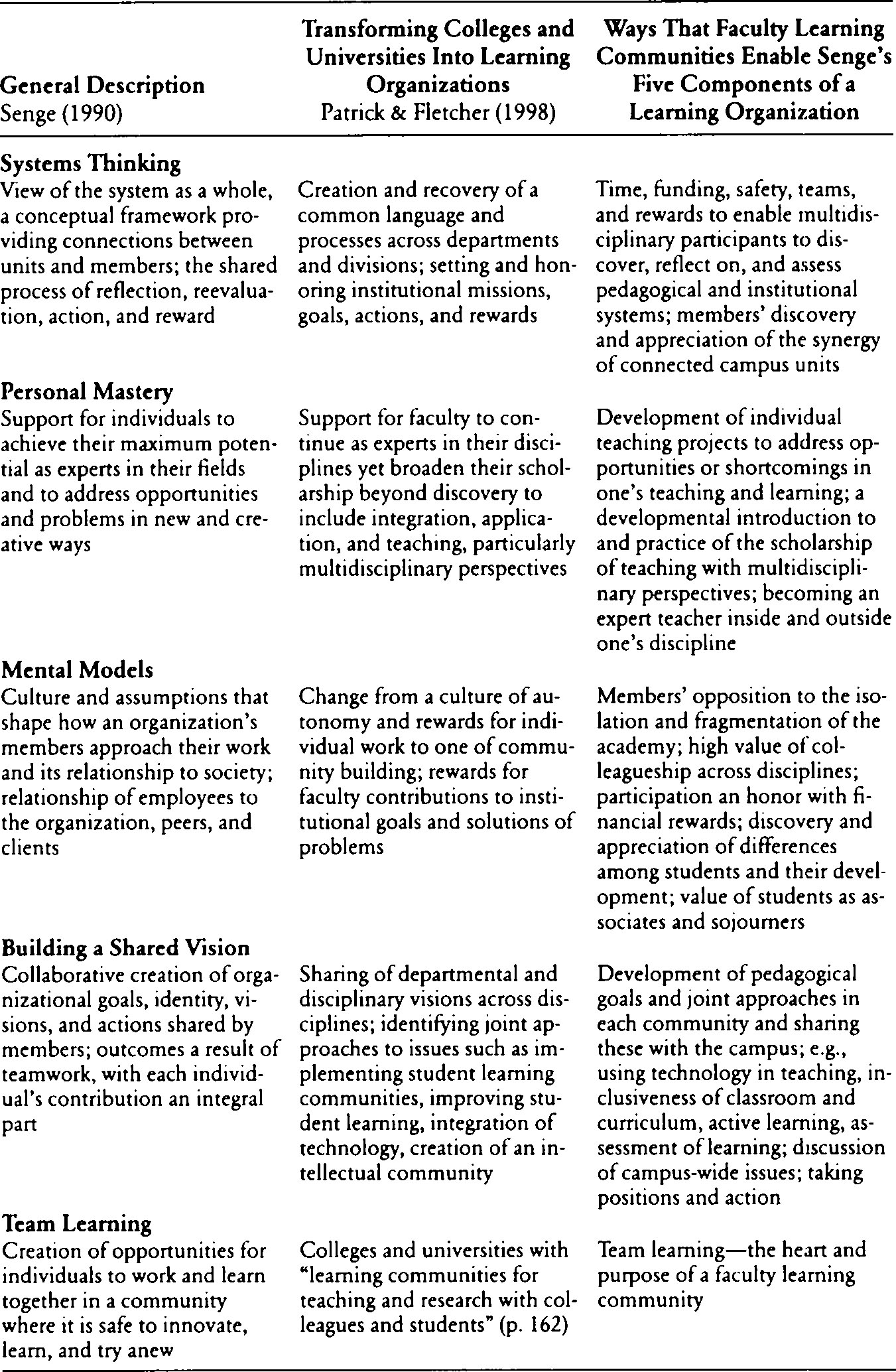

Senge (1990) describes a learning organization as one that connects its members closely to the mission, goals, and challenges of the organization. These close connections are necessary for the organization to meet the demands of rapid change. While faculty often have such connections within their departments and disciplinary organizations, faculty usually do not have the broad interests of their institutions at heart. There are few rewards for doing so—most are department- and discipline-based. Rarely has a turf battle in a university senate meeting (when a quorum could be mustered) been resolved by the opponents offering to consult and consider the university’s and students’ best interests. As a result, faculty remain isolated from colleagues in other disciplines, and the curriculum remains fragmented. Thus, both faculty and students miss out on connections across disciplines. Campus-wide action on issues (except, perhaps, parking and salaries) flounders from lack of interest, involvement, and support.

Senge (1990) describes the five components of a learning organization, components that foster close connections among the people within an institution. Patrick and Fletcher (1998) translate these components into behavior for the academy. Figure 5.3 describes both perspectives and shows how faculty learning communities foster the reflection, learning, and action needed to establish these components in our colleges and universities.

Evidence of Success

Figure 5.2 provides evidence that faculty learning communities produce team learning and community for their members: The program impact of “colleagueship and learning from other participants” is ranked first by those in each community. With respect to outcomes (Figure 5.1), the greatest impact of the cohort communities is on the participants’ interest in the teaching process. The greatest impact of the issue-focused communities is on the participants’ interest in the scholarship of teaching and view of teaching as an intellectual pursuit.

Figure 5.3 Senge’s Five Components of a Learning Organization and Ways That Faculty Learning Communities Enable Them

Figure 5.3 Senge’s Five Components of a Learning Organization and Ways That Faculty Learning Communities Enable ThemAnother measure of success is the support received from administrators. This is evident in that Miami’s provosts have tripled funding over the last 15 years to enable the initiation of new communities.

Evidence that communities foster civic pride is found in participants’ contributions to leadership of the university. Currently two of Miami’s six deans are graduates of faculty learning communities, as well as seven of 44 department chairs. Of the 146 faculty still at Miami who have served as mentors in the junior faculty community, over one-third (50/146) are former learning community participants. Of the 46 faculty members currently on the university senate, 16 (35%) are current or former members of faculty learning communities. Finally, of the 175 Miami faculty who volunteered to be on the 1998-99 faculty teaching resource list, 116 (66%) are former or current members.

Although effective faculty leaning communities alone will not transform an institution into a learning organization, over time they can produce a critical mass of key individuals and leaders plus the network necessary to connect campus units. Gabelnick et al. (1990) implore, “We need to create programs that bring us together structurally in some cases, intellectually and emotionally in others. . . . Learning communities are one way that we may build the commonalties and connections so essential to our education and our society” (p. 92). Harper (1996) contends that “Creating such opportunities for conversation and community among faculty is imperative, not only to the personal and professional growth and reflection of individual faculty, but also for the growth of the higher education community at large” (p. 265).

Learning communities, both faculty and student, can provide individuals, colleges, and universities with a means for achieving success in a rapidly changing world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the Miami faculty members who have coordinated faculty learning communities: Muriel Blaisdell, Interdisciplinary Studies—The Senior Faculty Community for Teaching Excellence; Phillip Cottell, Accountancy—The Faculty Community Using Cooperative Learning to Enhance Teaching and Learning; Mel Cohen, Political Science, and Martha Stevens, Communication—The Faculty Community Using Difference to Enhance Teaching and Learning. All of these colleagues have made terrific contributions to the common good.

REFERENCES

- Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Austin, A. E. (1992). Supporting junior faculty through a teaching fellows program. In M. D. Sorcinelli & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Developing new and junior faculty (pp. 73-86). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 50. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Barr, R. B. (1998, September-October). Obstacles to implementing the learning paradigm. About Campus, 3 (4), 18-25.

- Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995, November/December). From teaching to learning—A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27 (6), 13-25.

- Boice, R. (1992). The new faculty member: Supporting and fostering professional development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Brew, A., & Boud, D. (1996). Preparing for new academic roles. The International Journal for Academic Development, 1 (2), 17-26.

- Chism, N. V. N. (1998). The role of educational developers in institutional change: From basement office to front office. To improve the academy, 17, 141-154. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Cox, M. D. (1995). The development of new and junior faculty. In W. A. Wright & Associates (Eds.), Teaching improvement practices: Successful strategies for higher education (pp. 283-310). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Cox, M. D. (1996). A department-based approach to developing teaching portfolios: Perspectives for faculty developers. To improve the academy, 15, 275-302. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Cox, M. D. (1997). Long-term patterns in a mentoring program for junior faculty: Recommendations for practice. To improve the academy, 16, 225-268. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Cox, M. D. (1999a). Teaching communities, grants, resources, and events, 1999-00. Oxford, OH: Miami University.

- Cox, M. D. (1999b). Peer consultation and faculty learning communities. In

- C. Knapper & S. Piccinin (Eds.), Using consultation to improve teaching (pp. 39-49). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 79. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Cox, M. D., & Blaisdell, M. (1995, October). Teaching development far senior faculty: Searching.for fresh solutions in a salty sea. Paper presented at the 20th annual Conference of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, North Falmouth, MA.

- Cox, M. D., Cottell, P. G., & Stevens, M. P. (1999, October). Developing and coordinating faculty learning communities: Procedures and materials for practice. Workshop presented at the 24th annual conference of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, Lake Harmony, PA.

- Cox, M. D., & Sorenson, D. L. (2000). Student collaboration in faculty development: Connecting directly to the learning revolution. To improve the academy, 18, 97-127. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Cross, K. P. (1998, July-August). Why learning communities? Why now? About Campus, 4-11.

- Cross, K. P., & Steadman, M. H. (1996). Classroom research: Implementing the scholarship of teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Lexington, MA: Heath.

- Eckel, P., Kezar, A., & Lieberman, D. (1999, November). Learning for organizing: Institutional reading groups as a strategy for change. AAHE Bulletin, 52 (3), 6-8.

- Fulton, C., & Licklider, B. L. (1998). Supporting faculty development in an era of change. To improve the academy, 19, 51-66. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Gabelnick, F., MacGregor, J., Matthews, R. S., & Smith, B. L. (1990). Learning communities: Creating connections among students, faculty, and disciplines. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 41. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Harper, V. (1996). Establishing a community of conversation: Creating a context for self-reflection among teacher-scholars. To improve the academy, 15, 251-266. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Hubbard, G. T., Atkins, S. S., & Brinko, K. T. (1998). Holistic faculty development: Supporting personal, professional, and organizational well-being. To improve the academy, 17, 35-50. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Jones, R. (1981). Experiment at Evergreen. Cambridge, MA: Shenkman.

- Karpiak, I. E. (1997). University professors at mid-life: Being a part of . . . but feeling apart. To improve the academy, 16, 21-40. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Katz, J., & Henry, M. (1993). Turning professors into teachers: A new approach to faculty development and student learning. Phoenix, AZ,: Oryx.

- Kloss, R. J. (1994). A nudge is best: Helping students through the Perry Scheme of intellectual development. College Teaching, 42 (4), 151-158.

- Kreber, C., & Cranton, P. (2000). Fragmentation versus integration of faculty work. To improve the academy, 18, 217-231. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Kurfiss, J., & Boice, R. (1990). Current and desired faculty development practices among POD members. To improve the academy, 9, 73-82. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- List, K. (1997). A continuing conversation on teaching: An evaluation of a decade-long Lilly Teaching Fellows Program, 1986-1996. To improve the academy, 16, 201-224. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Meiklejohn, A. (1932). The experimental college. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

- Middendorf, J. K. (1999). Finding key faculty to influence change. To improve the academy, 18, 83-93. Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Millis, B. J. (1990). Helping faculty build learning communities through cooperative groups. To improve the academy, 9, 43-58. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape ofa teacher’s life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Patrick, S. K., & Fletcher, J. J. (1998). Faculty developers as change agents: Transforming colleges and universities into learning organizations. To improve the academy, 17, 155-170. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

- Perry, W. J. (1970). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Richlin, L. (in press). Teaching excellence, scholarly teaching, and the scholarship of teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Shapiro, N. S., & Levine, J. H. (1999, November-December). Introducing learning communities to your campus. About Campus, 4 (5), 2-10.

- Sorcinelli, M. D. (1992). New and junior faculty stress: Research and responses. In M. D. Sorcinelli & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Developing new and junior faculty (pp. 27-37). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 50. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Stevens, M. P., & Cox, M. D. (1999, October). Faculty development and the inclusion of diversity in the classroom: A faculty learning community approach. Paper presented at the 24th annual Conference of the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, Lake Harmony, PA.

- Taylor, P. G. (1997). Creating environments which nurture development: Messages from research into academics’ experiences. The International Journal for Academic Development, 2 (2), 42-49.

- Thomas, T. (1992). Connected teaching: An exploration of the classroom enterprise. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 3, 101-119.

- Tinto, V. (1995, March). Learning communities, collaborative learning, and the pedagogy of educational citizenship. AAHE Bulletin, 47 (7), 11-13.

- Tussman, J. (1969). Experiment at Berkeley. London: Oxford University Press.

- Wright, W. A., & O’Neil, M. C. (1995). Teaching improvement practices: International perspectives. In W. A. Wright & Associates (Eds.), Teaching improvement practices: Successful strategies for higher education (pp. 1-57). Bolton, MA: Anker.

Contact:

Milton D. Cox

University Director

Teaching Effectiveness Programs

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

(513) 529-6648

cixmd@muohio

Milton D. Cox is university director for teaching effectiveness programs at Miami University, where he founded and directs the annual Lilly Conference on college teaching. He also is founder and editor-in-chief of the journal on Excellence in College Teaching. He directs the 1994 Hesburg Award–winning teaching scholars’ community for junior faculty and oversees the other faculty learning communities at Miami. For the past 30 years he has taught mathematics, designing, and teaching courses that celebrate and share with students the beauty of mathematics. He incorporates the use of student learning portfolios and Howard Gardner’s concept of multiple intelligences in his mathematics classes. Cox has developed programs to enable the presentation of undergraduate student papers at national profession meetings. In 1988 he received the C. C. MacDuffee award for distinguished service to Pi Mu Epsilon, the national mathematics honorary society.

APPENDIX 5.1

FOCUS BOOKS FOR FACUL1Y LEARNING COMMUNITIES

These books are given to the community members at their opening retreat in May. They read them over the summer, and beginning seminars involve discussion of themes and issues raised in the reading.

Community Using Cooperative Learning to Enhance Teaching and Learning

(99-00) Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1998). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction.

Senior Faculty Community for Teaching Excellence

(99-00) Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

(98-99) Levine, A., & Cureton, J. S. (1998). When hope and fear collide: A portrait of today’s college student. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

(97-98) Schön, D. A. (1988). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

(96-97) Elbow, P. (1986). Embracing contraries: Explorations in teaching and learning. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Junior Faculty Learning Community

(several years) McKeachie, W. J. (1999). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

(several years) Grunert, J. (1997). The course syllabus: A learning-centered approach. Bolton, MA: Anker.

(several years) Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Community Using Difference to Enhance Teaching and Learning

(99-00) Tatum, B. D. (1997). “Why are all the black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?” and other conversations about race. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Miscellaneous Information

“There is a deep hunger among faculty members for more meaningful, collegial relationships and more ‘conversational structures’ in our institutions” (Gabelnick, MacGregor, Matthews, & Smith, 1990, p. 86).

- Engelkemeyer, S. W., & Brown, S. C. (1998, October). Powerful partnerships: A shared responsibility for learning. AAHE Bulletin, 51 (2), 10-12.

- Tosey, P., & Gregory, J. (1998). The peer learning community in higher education: Reflections on practice. Innovations in Education and Training International, 35 (1), 74-81.

- Palmer, P. J. (1997, December). Teaching & learning in community. About Campus, 2 (5), 4-12.