3 On the Path: POD as a Multicultural Organization

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Since 1993, the Professional and Organizational Development Network (POD) has made an increasingly stronger commitment to becoming a multicultural organization. Poised at the entrance to a new century, it seems useful to examine the current standing of this goal in the context of the overall growth and development of POD. In this article the authors take stock of the organization’s history related to multiculturalism, discuss POD’s current organizational strengths and challenges related to models of multicultural organizational development, and offer suggestions for further progress on the path to becoming a multicultural organization.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, linkages between diversity and teaching development efforts in the field of instructional development have centered on initiatives designed to raise individual student and faculty awareness levels and on the development and dissemination of models of inclusive classroom-based teaching practices. We need look no further than past issues of To Improve the Academy to trace a rich and ongoing dialogue within our field on models, strategies, and resources useful in fusing the best practices in multiculturalism and teaching development. Over time, these efforts have clustered along a continuum from initiatives for encouraging individual growth (Collett & Serrano, 1992; Cooper & Chattergy, 1993; Knoedler & Shea, 1992) to those directed more broadly, such as campus-wide interdisciplinary teaching development seminars (Ouellett & Sorcinelli, 1995, 1998; Schmitz, Paul, & Greenberg, 1992).

A concurrent theme in this same body of literature is that of educational developers as organizational change facilitators (Chism, 1998; Evans & Chauvin, 1993; Patrick & Fletcher, 1998). For some time now, POD members have been sensitive to the need for increased emphasis on the “O” (organizational) in POD Network activities. In particular, there is the call for a more systemic perspective on how we, as educational developers, address diversity-related issues of individual and institutional growth and development (Border & Chism, 1992; Cook & Sorcinelli, 1999; Wunsch & Chattergy, 1991). Chism (1998) offers a model for considering our role in organizational change that eloquently reminds us of our collective talents for conceptualizing, articulating, and implementing assessment and improvement efforts and the contribution of such assistance to long-term organizational health. More recently, we have been asked to strengthen our critique of classroom diversity-related experiences of students and faculty by analyzing more directly the systemic impacts of institutional context and campus climate (Chesler, 1998; Ferren & Geller, 1993). These streams of literature point to the role that multiculturalism and diversity have played in our emerging understanding of the nature of individual and institutional change in higher education.

Based upon public and private dialogues at the most recent annual POD Network conference, we found a merging of these themes. As a result of a series of conference events, we were reminded that POD offers members a natural context within which to explore, learn, and practice new perspectives and behaviors related to the changing nature of our organization. For many, the conference propelled us both to contemplate the distance we have traveled together and to speculate on the distance to the horizon still ahead of us. We came away from this annual gathering wondering how to renew our commitment to POD as a multicultural organization and what organizational “muscles” we need to strengthen to attain our goal of POD becoming an authentically multicultural organization.

Chesler (1994) defines a multicultural organization as one that articulates “an approach to organizational change that is frankly antiracist and antisexist . . . not simply an acceptance of differences, nor a celebrative affirmation of the value of differences, but a reduction in the patterns of racial and gender oppression (racism and sexism) that predominate in most US institutions and organizations” (pp. 243-244). A multicultural organization values and reflects the contributions of all its members. Specifically, it constantly re-examines current organizational structures, practices, and policies and readjusts efforts constantly to better manifest a diverse and socially just organization. The process of achieving a multicultural organization is evolutionary and occurs in stages. We would like to explore, within the context of POD and our home institutions, the nature of multicultural organizational development and how our role as faculty developers is integral to organizational, institutional, and individual change. First, we will look at the organization’s history with respect to these issues. Our examination will include exploring how we can advocate change, offering a model for conceptualizing a multicultural organization, and finally, inviting your call to action as we walk this path together in the future.

TAKING STOCK: DIVERSITY-RELATED INITIATIVES TO DATE

Reflecting on our past goals for organizational growth will better prepare us to assess development as a multicultural organization, to clarify our future aspirations, and to design concrete goals and strategies for fully realizing these commitments. In support of these efforts, POD already benefits from several unique strengths. These include its history of commitment to professional and organizational development; the organizational emphasis on community, collegiality, and networking; and its leadership role in the improvement of teaching and learning in higher education.

Let’s take a look at some of the initiatives and conversations that have taken place since the early years, with an eye toward how they continue to prepare us to become a multicultural organization. The POD Mission Statement, approved by the Executive Core Committee in 1991, has 16 explicitly articulated convictions relating to people and education. More specifically, related to diversity is the conviction that

[a] self-critical stance, self-assessment, and evaluation are important as a condition for both individual and organizational effectiveness and growth. . . . POD should strive at all points to be responsive to human needs. . . . [A]s our members change and as higher education changes, so POD must change.

It is a direct result of self-assessment, critical reflection, and commitment that led POD to respond to its members’ growing desire to shape a multicultural organization. Within a year of the approval of the POD Mission Statement, members helped initiate a number of specific steps to be taken by POD, including the formation of the Diversity Commission and reexamination of the goals of the organization.

The Membership Calls and the Executive Core Responds

In 1992, our annual conference was held at the Saddlebrook Resort in Tampa, Florida. At this conference 24 of our members came together to form a Diversity Interest Group. Their first action was to write a letter to the Executive Core Committee to suggest ways in which POD could encourage a more diverse membership base for the organization. At the heart of the conversations was a realization that we needed to attract a broader membership in our efforts toward becoming a more multicultural organization.

In 1993, under the presidential leadership of Don Wulff, a volunteer group began to explore organizational models for diversity. After looking at efforts within other, related higher education organizations (e.g., American Association for Higher Education), they developed and presented a proposal to the Executive Core Committee. This proposal focused on ways to make diversity a priority within POD and articulated the necessity of making diversity an explicit goal in membership outreach to underrepresented groups and institutions.

The Diversity Commission: A Focus on Recruitment

In 1994, this proposal was presented and accepted, and members who were charged with its implementation were given a budget to begin developing this work for the organization. They formed a Diversity Committee, which was later renamed the Diversity Commission. As members of the Diversity Commission, we first focused our efforts on outreach to institutions and groups that had historically been underrepresented in the organization. We began to network with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Native American tribal colleges, and Hispanic-serving institutions. Between 1994 and 1998, the Commission successfully recruited 31 underrepresented institutions to our annual conference.

Between 1993 and 1997, we were aware that, although the commission was established with a recruitment goal in mind, we were increasingly consulted about other organizational efforts toward diversity, such as conference and program planning, conference site selection, publications, and the like. We welcomed these opportunities to consult across the organization. What began as a general recruitment initiative became a conceptual springboard for broader organizational assessment and changes. We know that recruitment is synergistically tied to retention. We were determined that POD not continue to recruit individuals from underrepresented groups and institutions without also paying attention to what their experiences were like once they arrived in the organization. Efforts toward valuing diversity may begin with recruitment, but not changing the nature of the organization to provide for ongoing retention of our new members is counterproductive. In fact, it sends a clear message to these members that they are invited to assimilate organizational norms and values, but not to influence or change core values and mission.

In 1995, an internship opportunity, the POD faculty/instructional development training grant program, was developed. The purpose of this program is to provide a POD member institution with funding to support an internship for a person of color who wishes to explore professional opportunities in faculty/TA instructional development. The sponsoring unit would then assist the intern in searching for a position in faculty development. To date, three campuses have received funding for this initiative: The University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT), the University of Southern Colorado’s Faculty Center for Professional Development, and the Center for Teaching (CFT) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. While admittedly supporting campus-based initiatives, this program has enabled recipients to provide education and training for faculty and TAs of color considering faculty development as a career. Grants have been used for networking activities, training in teaching consultations and assessment, and attendance at national and regional conferences.

The Diversity Commission: A Focus on Organizational Development

In 1998, another proposal was developed by the Commission and presented to the Executive Core Committee suggesting ways that the organization could work toward valuing diversity. In this proposal, current initiatives and the mission of the commission were redefined to enable more qualitative outcomes—for example, for us to become more self-reflective about how those in our organization and profession do their work. We realized that in order for us to better respond to efforts to accomplish a broader scope of involvement throughout our work and the membership, we needed to work more closely together with the Executive Core Committee, serving in both advocacy and education roles. This extended our charge to advising the Executive Core Committee on ways to increase and sustain the organization’s efforts toward valuing diversity.

The Executive Core Committee: A Focus on Organizational Commitment

In the spring 1999 Executive Core Committee meeting, under the presidential leadership of Kay Herr Gillespie, leaders articulated 11 goals for the organization. These goals were then prioritized in terms of future direction. Among the important goals listed was for the organization “to enhance the centrality of diversity and multiculturalism within POD’s mission.” In striving to meet this goal, several objectives were shared. These included, but were not limited to, (1) conducting a multicultural values assessment of POD, (2) conducting a multicultural climate assessment of POD, (3) conducting an assessment of possible differences in perceptions between underrepresented and majority group members, and (4) increasing our sensitivity to new members of the organization so that we do not polarize ourselves into an “in-group” and an “out-group.”

When one looks at the history and culture of POD since its founding in 1976, we can see regular efforts made toward valuing diversity. These efforts have been uneven, however, in terms of conference keynotes and themes; programming streams; our literature; the social, cultural, and racial identity makeup of our members; the types of institutions represented in our membership; the leadership makeup of the Core; and the level of commitment among our members. At best, our practices could be considered localized, with organizational initiatives undertaken by colleagues who not only demonstrated a strong personal commitment toward this work, but who often also were driven by compelling forces or needs at their institutions.

We remain encouraged that many of the current values, policies, and practices of POD (only some of which are described here) constitute important institutional strengths in advancing our progress toward the realization of a multicultural organization. For example, POD members value highly the spirit of collegiality and flexibility. Over and over, many first-time conference attendees remark on the generosity of POD members in sharing their ideas, programs, materials, and resources so willingly. We also have a growing historical record of formal organizational support for diversity initiatives. However, more remains to be achieved, especially at the organizational level.

CALIBRATING THE DISTANCE: HOW DO WE GET FROM HERE TO THERE?

Attempts to understand the current context and to explore future directions for change in instructional and organizational development within POD, as well as our home institutions, might benefit from taking a multicultural organizational change perspective. As surveyed above, POD has begun to genuinely engage in creating organizational supports for diversity. We actively support outreach efforts, offer access to funds and internships, and actively nurture networks to mentor members from underrepresented institutions and racial and ethnic groups. However, the dominant values, practices, systems, politics, and guiding principles of POD continue to reflect our historically homogenous (white) character.

The theoretical perspectives and practices of multicultural organizational development provide particularly useful models and strategies as we reflect on where we are now and consider next steps as a multicultural organization. Multicultural organizational development (MCOD) offers systemic organizational change models that directly address social justice and equity issues in terms of the growth and development of organizations (Jackson & Holvino, 1988). These frameworks for addressing social justice issues in organizational development have emerged through the efforts of both practitioners and theorists since the 1970s. The work of Jackson and Holvino (1988) and field practitioners like Cross (1994) continue to directly address issues of equity and social justice in an organizational development context.

Multicultural organizational development theory enhances and extends the field of organizational development by articulating the relatedness of organizations to culture-wide change initiatives and by addressing the impact of cultural, institutional, and individual socialization (Jackson & Holvino, 1988; Katz, 1978). Like the field of organizational development before it, multicultural organizational development takes a systemic perspective and includes every aspect of an organization (mission, resources, processes, product, and people) as equally important components of growth, and it emphasizes change toward social justice.

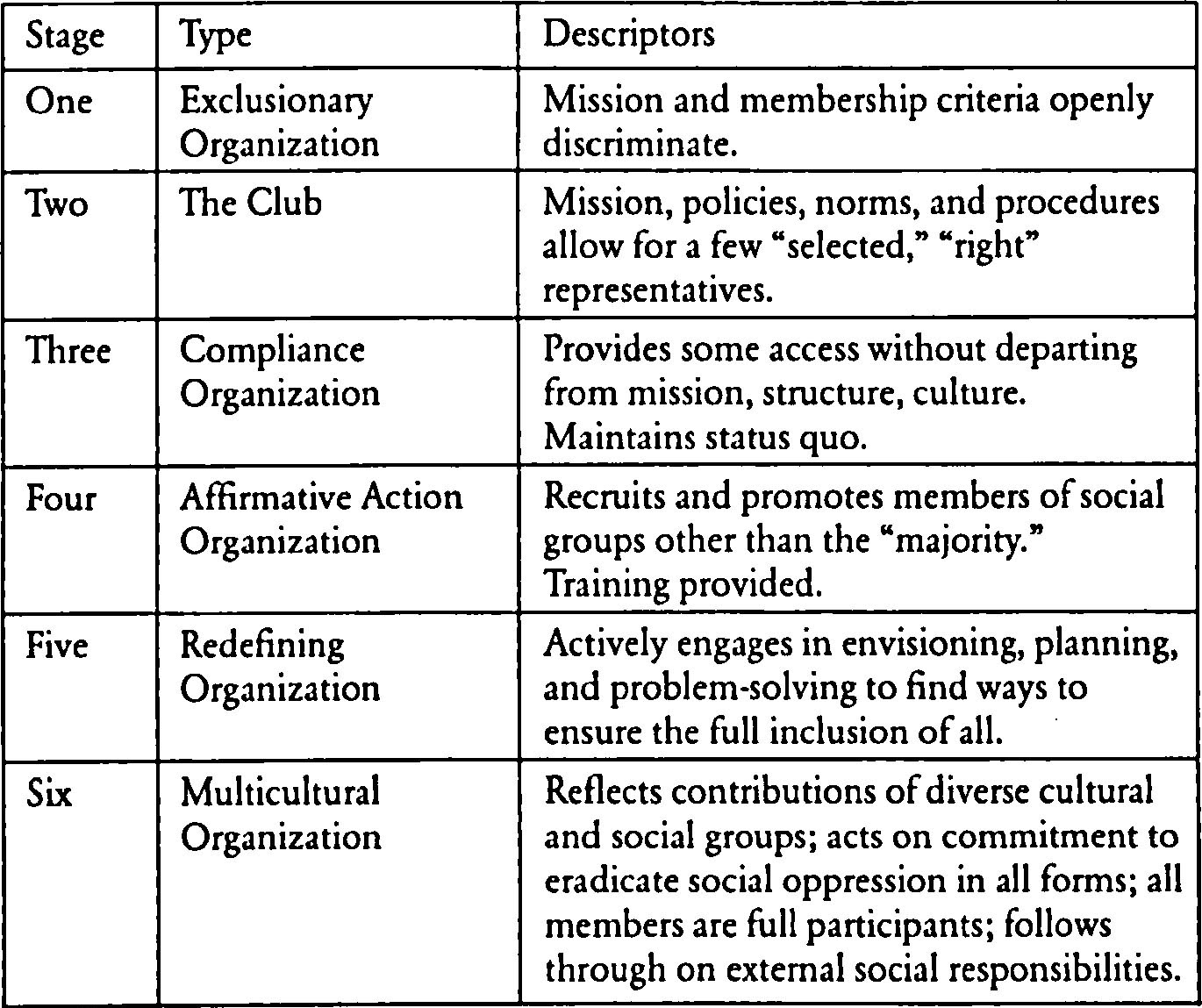

Jackson and Hardiman (1994) have described six developmental stages through which an organization may move from a monocultural to a multicultural organization. These stages include the exclusionary organization, the “club,” the compliance organization, the Affirmative Action organization, a redefining organization, and, finally, the multicultural organization (see Figure 3.1). One of the strengths of this multicultural organizational development model is that it offers multiple points of entry into systems-change and goals for a more socially just organization. For example, MCOD advocates organizational change by comprehensively addressing the organization’s mission, goals, and values; structure and personnel profile; technology; management practices; and awareness and climate (Jackson & Hardiman, 1994). The model ultimately addresses the way our organization interacts with the larger societal environment in achieving our “bottom line” goals. Any one of these organizational elements provides a productive place to begin the work of transforming POD into the multicultural organization many of us envision.

FIGURE 3.1 Stages in the Development of a Multicultural OrganizationFrom Jackson, B. & Holvino, E. (1988). Developing multicultural organizations. Creative Change: The Journal of Religion and the Applied Behavioral Sciences, 9 (2), 14-19. Association for Creative Change.

FIGURE 3.1 Stages in the Development of a Multicultural OrganizationFrom Jackson, B. & Holvino, E. (1988). Developing multicultural organizations. Creative Change: The Journal of Religion and the Applied Behavioral Sciences, 9 (2), 14-19. Association for Creative Change.In moving through different stages in the development of a multicultural organization, Jackson and Hardiman (1994) suggest a four-component process of organization-wide, long-term change strategy. These components include the creation of a multicultural change team, a support building phase, a leadership-development phase, and a self-renewing, multicultural systems-change process. We are absolutely confident that POD counts within both its general membership and the Executive Core leaders the experience, expertise, and commitment to guide our organization successfully through these endeavors.

Multicultural Internal Change Team

Dialogues currently underway within the organization provide a measure for our organization’s state of readiness for further change initiatives. By better assessing how our organization currently functions, defines itself, and understands the need for change, we can develop meaningful interventions and develop practical strategies that more inclusively extend the opportunities and benefits many of us have harvested from our association with POD to others.

The Diversity Commission has played just such a powerful and important role as an internal change team. Its efforts have ranged from helping individual members increase their self-awareness to efforts to influence the organizational environment for all members. As a membership, we must realize that there may be times when we are going to feel “uncomfortable,” but at the same time, we should find ways of dealing with this discomfort by having open and honest dialogues with each other. Recognizing that change is a concept integral to life and that we must continually learn in order to be effective will also help us to value the fundamental reason for becoming a multicultural learning organization.

As educational developers, we can assist our home institutions by helping groups learn of multicultural faculty development models that they can employ in creating climate change on campus. Nowhere is this call for us to be change agents advocated more strongly than by Chism (1998):

As messengers and translators, educational developers need to be able to follow developments under discussion in the current literature and educational meetings and communicate these in a way that will be understood by their faculty and administrators, using the language that is appropriate for the context. . . . As nurturers, partners and coaches, we need to be personally centered, knowing our own capacity and believing in the capacity of our colleagues to recognize the need for change and be brave enough to experiment (p. 146).

Efforts of the Diversity Commission have fostered this kind of coaching for the organization’s members and leadership team.

Support Building

A useful strategy for encouraging support building in an ongoing manner is to engage ourselves in a self-reflective process that continues to clarify our values and the cultural context in which these are embedded (Stanley & Ouellett, 1998). We can begin to open ourselves to change by exploring ideas, models, activities, action plans, and strategies that can be accomplished in the context of our home institutions. Some of these could involve high-risk activities such as multicultural audits, where systematic data are gathered to gain insight into an organization’s life (Chesler, 1998). Equally important is to engage in candid dialogues with peers or students who have traditionally been seated on the “outside aisles” of our institutions. Lower-risk activities could involve expanding our knowledge base (Kardia, 1998) by bringing the scholarship of diversity into conversations or attending a workshop.

Leadership Development

Leadership is key to change initiatives; without it most change fails (Chaffee & Tierney, 1988; Kouzes & Posner, 1990). POD has had and will continue to have a history of strong leadership in both formal (Executive Core Committee) and informal (member-based initiatives) structures. We have had a lineage of leaders who have been instrumental in creating and responding effectively to changes within higher education in general and within POD specifically. Organizational leaders have been especially effective in creating a shared responsibility for the values and mission among the membership. Becoming a multicultural organization begins with visionary leadership for the future. We have to become more self-reflective leaders and practitioners, as we discuss successes, challenges, and intentions. It is not a static event, but rather a continuous process (Cook & Sorcinelli, 1999). It is part of being a learning community. It is part of becoming organizational change agents.

Self-Renewing Multicultural Systems-Change Process

Change is complex, nonlinear, and healthy. As we look at POD as an example, change, on one level, can be viewed in terms of increased membership, while on another, it can be seen as the way we envision our work as a national organization. At an organizational level, two modes of inquiry may be useful: One is to clarify our organizational values (what they mean to us individually and collectively), and the other is to clarify and reiterate how we express our commitment to these values (policies, procedures, resources, access). We have to continue to ask ourselves more guiding questions as we work toward this endeavor. Some might be: What do we really mean by diversity? Is it cultural diversity? Is it social diversity? Is it institutional diversity? What does the choice of conference site location or programming say to our members who are socially and culturally diverse (e.g., people of color, gays and lesbians, people with disabilities, etc.)?

As authors, our perception of POD is offered as one way to begin a discussion. A determination of POD’s stage of multicultural organization development, identification of goals, and development of interventions to move us to the next stage of development require the participation of many more and diverse perspectives. What messages do we send when members of the Diversity Commission are the ones leading the charge for these issues? What are some ways that we can engage other POD committees in building diversity in their own activities? Why is it important for POD to diversify its membership to reflect faculty development efforts nationally?

In our dialogues, we cannot lose sight of the big picture. A multicultural organization allows everyone a voice to express their concerns and different perspectives about the reasons for change and the desired outcomes. Disagreement will be inevitable and should be welcomed. In developing a structure for change, leadership at all levels is important (Morey, 1997).

For example, the Professional Development Committee could develop ideas for opening the pipeline to faculty developers of color, or it could work with POD institutions who have been recipients of the diversity internship grants to involve interns in the Institute for New Faculty Developers. The Grants Committee could seek out and call for proposals that have a diversity strand. The Publications Committee could, in its guidelines, seek out and call for papers that have a focus on diversity. Similarly, the Long Range Conference and Conference Planning Committees could take into account factors that contribute to the climate of a successful conference. All committees, in their reports, budgets, and timelines for accomplishing proposed activities, could be asked to report on how goals are met with respect to valuing diversity.

A CALL TO ACTION

As we lay the foundation for becoming a multicultural organization, we can work toward self-awareness by stretching beyond our own “comfort zone” (Stanley & Ouellett, 1998) and by utilizing the experiences we share in POD to create a vital, flexible learning community. As we look toward the new century, let us not forget this goal, but rather embrace it with purpose, so that together we can build a compelling and dynamic vision for the future. As educational change agents, we can work together to develop effective communication networks and strategies in the continual search for ideas as we assess our successes and failures and decide on next steps. Jackson (1994) underscores that

to create a vision of a multicultural system, a diversity of perspectives must be represented in a group of people who are engaged in a dialogical process such as that put forth by Paulo Freire as Praxis. . . . The people involved in this process are as important as the process itself (p. 116).

Based on our experiences and research, we would like to invite you to continue this dialogue. As we collectively shape our goal of becoming a multicultural organization, we leave you with some concrete suggestions for where to begin.

1) Ask Questions. We can only improve on what we have accomplished and gather information for future directions by asking questions. Talk to each other. Talk to colleagues who work at institutions that are different from your own. Talk to colleagues who are from a different social, racial, or cultural group. Articulate a vision for the future of the organization.

2) Take More Risks. Be an effective educational ally for change. Effective allies are supportive of, and advocates for, change. Allies have worked to develop an understanding of the personal and institutional experiences of target group members (e.g., people of color; gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals; people with disabilities; women; etc.). Effective allies choose to align themselves publicly and privately with members of targeted groups. Often, retooled skills and reexamined perspectives are part and parcel of genuine commitment to new initiatives.

3) Respect and Forgive. In learning together, we will make mistakes. Hopefully, we will learn from our mistakes and our encounters and not use them as excuses for non-action. Many of us, after reflecting on our own behaviors during the last conference, have decided to be more proactive in terms of making multicultural issues more integral to programming streams and overall conference planning.

4) Engage in Sustained Dialogue. A vision for a multicultural organization can grow from multiple sources. We need everyone’s input and perspectives if we are to make a difference.

5) Start in Our Own Backyard. POD offers an opportunity to practice the development of these skills and behaviors in a context that is less risky than what most of us would find at our home institutions. It provides a supportive system of collegiality and a highly expert network of professionals in a setting that values and nurtures educational development.

6) Start Where You Are. There are multiple points of entry into this process and we have to consider what we are ready to do publicly and what we would rather do reflectively.

CONCLUSION

We suggest that multicultural organizational change models, such as those by Jackson and Hardiman, can help us to acknowledge the useful contributions of current diversity initiatives in POD as well as to structure significant innovations. As we roll toward the 21st century, becoming a multicultural organization stands to benefit all of our members. The models and practices offered by multicultural organizational development theorists acknowledge an underlying commonality of forms of oppression and suggest that intervention to interrupt one manifestation (e.g., racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, ableism, or heterosexism) lays groundwork for interventions around others (Jackson & Holvino, 1988). Some POD members currently gain many advantages from the current values, beliefs, and practices of the organizational culture and, therefore, may be less motivated to act to support change. However, there are benefits for all members because participation in this process becomes an opportunity to learn and practice the skills needed in most meaningful future leadership roles both within POD and at most educational institutions.

Our experience has taught us that systemic organizational change is not without its ups and downs. To be sure, since our involvement in POD, we have seen many changes that would not have occurred without all of our efforts. As changes occur, we continue to grow and learn from the knowledge gained and the satisfaction that we have contributed to respecting and valuing human diversity. This is essential to the organizational growth and continued excellence of POD as well as to our professional and personal growth as educational developers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the counsel and perspective of Kay Herr Gillespie, Mary Deane Sorcinelli, and Marilla Svinicki during the development of this article.

REFERENCES

- Border, L. L. B., & Chism, N. V. N. (1992). The future is now: A call for action and list of resources. In L. L. B. Border & N. V. N. Chism (Eds.), Teaching for diversity (pp. 103-115). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 49. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Chaffee, E. E., & Tierney, W. G. (1988). Collegiate culture and leadership strategies. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Chesler, M. A. (1994). Organizational development is not the same as multicultural organizational development. In E. Cross, H. Katz, F. Miller, & E. Seashore (Eds.), The promise of diversity (pp. 240-251). Chicago, IL: Irwin Professional Publishing.

- Chesler, M. A. (1998). Planning multicultural audits in higher education. ToImprove the Academy, 17, 171-192.

- Chism, N. V. N. (1998). The roles of educational developers in institutional change: From the basement office to the front office. To Improve the Academy, 17, 141-153.

- Collett, J., & Serrano, B. (1992). Stirring it up: The inclusive classroom. In L. L. B. Border & N. V. N. Chism (Eds.), Teaching for diversity (pp. 35-48). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 49. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Cook, C. E., & Sorcinelli, M. D. (1999). Building multiculturalism into teaching-development programs. AAHE Bulletin, 51 (7), 3-6.

- Cooper, J., & Chattergy, V. (1993). Developing faculty multicultural awareness: An examination of life roles and their cultural components. To Improve the Academy, 12, 81-95.

- Cross, E. (1994). Truth-or consequences. In E. Cross, H. Katz, F. Miller, & E. Seashore (Eds.), The promise of diversity (pp. 32-35). Chicago, IL: Irwin Professional Publishing.

- Evans, L., & Chauvin, S. (1993). Faculty developers as change facilitators: The concerns-based adoption model. To Improve the Academy, 12, 165-178.

- Ferren, A., & Geller, W. (1993). Faculty development’s role in promoting an inclusive community: Addressing sexual orientation. To Improve the Academy, 12, 97-108.

- Jackson, B. (1994). Coming to a vision of a multicultural system. In E. Cross, H. Katz, F. Miller, & E. Seashore (Eds.), The promise of diversity (pp. 116-117). Chicago, IL: Irwin Professional Publishing.

- Jackson, B., & Hardiman, R. (1994). Multicultural organizational development. In E. Cross, H. Katz, F. Miller, & E. Seashore (Eds.), The promise of diversity (pp. 231-239). Chicago, IL: Irwin Professional Publishing.

- Jackson, B., & Holvino, E. (1988). Developing multicultural organizations. Creative Change: The journal of Religion and the Applied Behavioral Sciences, 9 (2), 14-19. Association for Creative Change.

- Kardia, D. (1998). Becoming a multicultural faculty developer. To Improve the Academy, 17, 15-33.

- Katz, J. (1978). White awareness: Handbook of anti-racism training. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Knoedler, A., & Shea, M. (1992). Conducting discussions in the diverse classroom. To Improve the Academy, 11, 123-135.

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1990). The leadership challenge: How to get extraordinary things done in organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Morey, A. I. (1997). Organizational change and implementation strategies for multicultural infusion. In A. I. Morey & M. K. Kitano (Eds.), Multicultural course transformation in higher education: A broader truth (pp. 258-277). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Ouellett, M. L., & Sorcinelli, M. D. (1995). Teaching and learning in the diverse classroom: A faculty and TA partnership program. To Improve the Academy, 14, 205-217.

- Ouellett, M. L., & Sorcinelli, M. D. (1998). TA training: Strategies for responding to diversity in the classroom. In M. Marincovich, J. Prostko, & F. Stout (Eds.), The professional development of graduate teaching assistants (pp. 105-120). Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing.

- Patrick, S., & Fletcher, J. (1998). Faculty developers as change agents: Transforming colleges and universities into learning organizations. To Improve the Academy, 17, 155-169.

- Schmitz, B., Paul, S., & Greenberg, J. (1992). Creating multicultural classrooms: An experience-derived faculty development program. In L. L. B. Border & N. V. N. Chism (Eds.), Teaching for diversity (pp. 75-87). New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 49. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Stanley, C. A., & Ouellett, M. L. (1998). Teaching for the diverse classroom. Advocate, 1 (2), 5-8.

- Wadsworth, E. (1992). Inclusive teaching: A workshop on cultural diversity. ToImprove the Academy, 11, 233-240.

- Wunsch, M., & Chattergy, V. (1991). Managing diversity through faculty development. To Improve the Academy, 10, 141-150.

Contacts:

Christine A. Stanley

Office of Faculty and TA Development

The Ohio State University

20 Lord Hall, 124 West 17th Avenue

Columbus, OH 43210-1316

(614) 292-3644

(614) 688-5496 (FAX)

Mathew L. Ouellett

Center for Teaching

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

301 Goodell Building, Box 33245

Amherst, MA 01003-3245

(413) 545-1225

(413) 545-3205 (FAX)

Christine A. Stanley is Associate Director of the Office of Faculty and TA Development and a member of the Adjunct Faculty in the School of Educational Policy & Leadership at The Ohio State University. She has taught courses in College Teaching and General Biology. Her research interests include professional development in higher education, how to deliver effective consultation services to faculty and TAs, and multicultural faculty and organizational development. She is President-Elect of POD.

Mathew L. Ouellett is Associate Director of the Center for Teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He also serves as Adjunct Professor of Social Work at Smith College, where he teaches courses on the implications of racism for clinical social work practice. His research interests include faculty development, multicultural organizational development, and equity in educational organizations. He is Vice Chair of the POD Diversity Commission.