Teaching the Technology of Teaching: A Faculty Development Program for New Faculty

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The primary function of institutions of higher education is to facilitate learning. New faculty are hired yearly with the expectation that they will match student needs with effective learning experiences. But many incoming faculty, although knowledgeable in their fields, enter higher education with limited preparation or experience in teaching. This can reduce the effectiveness of the teaching/learning process. The question is: “How can faculty with limited teaching experience be helped to strengthen their teaching effectiveness?” To examine this question, this article will describe the development, implementation, and qualitative and quantitative assessment of an innovative faculty development program entitled “Teaching the Technology of Teaching” (TTT).

In 1989, a report, entitled “The Business of the Business,” emerged from a series of wide-ranging discussions by college presidents, university deans, professors, and education policy-makers. The report stated that many college teachers have never had any formal training in teaching. Arthur E. Levine, former President of Bradford College and now at Harvard, said that those who prepare college teachers “focus entirely on subject matter and hope that pedagogy will occur by osmosis” (Berger, 1989). Each year new faculty are hired with the expectation that they will match student needs with effective instruction. However, many incoming faculty, although knowledgeable in their field, enter higher education with limited preparation or experience in teaching. This can reduce the effectiveness of the teaching/learning process by accenting the problems of integrating course content and instructional strategies with the needs and learning styles of students.

Just as students need guidance to enhance learning, university faculty need helpful direction to improve their teaching and understand the complexities of the academy. The question is, “How can faculty — with limited preparation or experience in teaching — be helped to strengthen their teaching effectiveness?” To examine this question, this article will describe the (1) development, (2) implementation, and (3) qualitative and quantitative assessment of an innovative faculty development program entitled “Teaching the Technology of Teaching” (TTT).

Development of the TTT Program

In 1987, the Ball State University Foundation funded a pilot faculty development program to reduce the problems often encountered by new faculty and to enhance their teaching effectiveness. The grant was in response to a proposal submitted by the program coordinators (Henak and Shackelford 1987) proceeding from the premise that faculty, with limited backgrounds in teaching, often based their teaching practices upon personal experiences rather than on a sound understanding of the teaching/learning process. In other words, new faculty tend to teach as they were taught. The four program objectives were to help participating faculty:

Enhance their understanding of student characteristics and needs.

Develop and use effective teaching strategies, media, and environments.

Improve their ability to identify, communicate, and implement intended course outcomes, content, and experiences.

Develop an ability to assess and evaluate student understanding, progress, and achievement.

The program name, Teaching the Technology of Teaching, was selected to reflect a common understanding of the term technology — the study of efficient practices. In this case, the efficient practice is reflected in the literature on the characteristics of good teachers and the effective strategies used to enhance teaching and learning.

The development of the TTT program followed a planned sequence of work divided into six major tasks. These included: collecting baseline data, identifying content, determining assessment strategies, designing promotional strategies and materials, developing instructional strategies, and developing support materials.

Collection of Baseline Data and Identification of Program Content

The development of the TTT program was based upon the works of Turner and Boice (1987), Mohan (1975), Kerwin (1987), Chickering and Gamson (1987), and McKeachie (1986) and the results of a needs survey administered by Shackelford and Henak (1987) to 31 newly hired Ball State University faculty. Twenty faculty completed and returned the survey. The survey gathered information about their educational backgrounds; teaching experience; use of instructional strategies, assessment procedures, and media; and perceived teaching strengths and weaknesses. The results of the survey and literature review suggested that newly hired professors could benefit from faculty development activities in the following areas: (a) course organization and management skills, (b) communication skills, (c) presentation techniques, (d) active participation strategies, and (e) student and teaching assessment techniques.

As the needs of faculty with limited teaching preparation or experience became clearer, topics or areas of content were identified. The TTT program was offered as a sequence of twelve integrated seminars (Figure 1). This decision was based upon discussions with other faculty developers at their institutions or selected professional conferences (e.g., the Lilly Conference on College Teaching and the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education conference). To facilitate communication and program promotion, topics were grouped into three major program thrusts — planning, teaching, and professional development (Figure 2). It also should be noted that the TTT seminars are not designed to be presented in a pick and choose fonnat. Faculty apply to participate in the program and make a professional commitment to attend all twelve sessions. During the fall semester of 1988, 6:30 - 8:30 p.m. sessions were offered on Tuesday and Wednesday to accommodate program demand — with a limit of twenty in each session.

Assessment Strategies

The collection of baseline data included the preparation of a teaching assessment instrument using questions from the Instructor and Course Appraisal: Purdue Research Foundation form (1974). This instrument was administered to newly hired faculty with limited teaching experience or preparation (i.e., average of 4 years teaching experience) during the 1987 school year. The purpose of this effort was to establish a control group (non-TTT program participants) to which the performance of TTT participants could be compared. The instrument and the results of this comparison will be discussed later in the section on program assessment.

Program Promotion

When starting a new faculty development program, communication and program promotion can not be overemphasized. Meetings were held with the deans or associate deans of each college to discuss the targeted population, potential values of the program, application procedures, and program format. Following these meetings, promotional materials were prepared and mailed to all incoming new faculty and all university department heads and college deans. Materials for faculty explained the program and its values, and materials for administrators requested that they recommend the program to faculty based on their perceived needs.

Instructional Strategies and Program Materials

Two decisions were made early in the development of the program: the participants would actively use, demonstrate, and share instructional strategies and teaching techniques; and session facilitators would consciously model good teacher characteristics. A series of readings were prepared to support the seminars, one reading for each topic. Support materials, such as visuals and activities, also were developed. Strategies for presenting content included: reflective practices, informal and formal presentations, group discussion, problem-solving, media presentations, self-assessment, presentation and video-taping of mini-lessons, video consultation, preparation of instructional materials using computers, questioning, and individual/small/large group activities and interaction. Guest presenters or facilitators also were used for selected topics.

One of the strengths of the program is the combination of techniques, strategies, and materials used to support content delivery, retention, and application. For example, interaction techniques are presented using questioning, discussion, interviews, etc., and characteristics of good teachers are introduced by asking participants to name and then actively discuss the characteristics of their favorite or best teacher. In many instances, numerous instructional techniques are used (e.g., modeling of a concept, wait time in questioning, cooperative learning, anticipatory sets, etc.) and later expounded upon. Thus, participants often observe or participate in a technique and make judgments about its effectiveness before being informed of the technique’s name (e.g., modeling). In this manner participants are often introduced to and successfully use different techniques without realizing they are planned program content. And, in a conscious effort to create an atmosphere that encourages active participation, facilitators:

actively involve and use the expertise of the participants and other recognized faculty and administrators on campus;

create a relaxed, informal, supportive, and non-judgmental atmosphere;

display enthusiasm about each evening’s topic and activities — as well as their own teaching;

clearly communicate, model, and provide examples to reinforce topics under discussion;

introduce the following week’s topic with some hook, teaser, or question;

come well-prepared and early enough (at least one hour before each session) that one-on-one conversations are possible with participants as they arrive for the session;

strive to provide something in each session that participants can immediately use.

Program Implementation

As funded by the Ball State University Foundation, the TTT program included support for one year of program development and its pilot during the Fall Semester of 1988. Based upon the program’s success, an increasing number of former participants have recommended the program to other faculty. In 1991, forty-five faculty applied for the twenty available slots, requiring the implementation of a Spring program for the first time. In 1992, thirty-two faculty applied for the twenty available slots in the Fall program. Between 1988 and 1992, over 140 faculty had participated in the program as either participants, quest speakers, or facilitators.

When compared to other faculty development programs, the TTT program has several commonalties as well as unique characteristics. Some of these features include:

The program is designed to help new faculty develop a sense of community and provide an opportunity to enhance their understanding of the academy and readiness to teach.

Participation in the program is completely voluntary, with faculty having to apply to participate in the program.

Faculty receive no compensation or released time to participate in the program. In fact, they do not even receive the typical free lunch that is common in many faculty development programs.

The administration is informed of a faculty member’s participation in the program, but judgments regarding the participant’s teaching effectiveness are not communicated to the administration.

Participants work closely with master teachers in the seminars and with mentors in their departments.

Good teacher behaviors are modeled during the seminars. Participants then practice the techniques during the seminars and in their classes and discuss their experiences. Related faculty development efforts and programs provide follow-up and continued support for participants’ needs and topics introduced in the program.

Mini-lessons are videotaped and analyzed to (a) give the teacher an opportunity to view themselves from an outsider’s perspective and self-diagnose their teaching and (b) provide a skilled faculty developer to help analyze and suggest modifications in particular practices and teaching behaviors.

Teachers are encouraged to use a variety of student, peer, and self-assessment strategies and to collect information about their teaching effectiveness several times during the semester.

Based upon participant feedback, the program has gone through several changes. To enhance presentation skills, a session utilizing videotape analysis of previously presented mini-lessons was substituted for a session which focused on communicating course outcomes (course objectives and descriptions). In addition, changes occurred in the use of media to support each session. Media support in the program moved from a primary dependence on overhead transparencies to a more diverse use of overheads, slides, computers, models, charts, video tape, LCD computer projection, video floppies, and the university’s Visual Information System (VIS).

Program Assessment

Qualitative and quantitative assessments indicate that the program is appreciated by faculty and enhances teaching effectiveness. Quantitative measures were based upon instructor and course appraisal data comparing the differences between the control (non TTT participants) and treatment groups (TTT participants). Qualitative feedback includes letters of support, comments to administrators, and individual seminar feedback assessments. Both forms of assessments were used to determine levels of participant understanding and application of TTT content, effectiveness of seminar facilitators, success of the program as well as for program revision.

Qualitative Assessment of the TTT Program

At the end of each seminar, seminar feedback forms are provided to determine its effectiveness. Figure 3 illustrates a sample feedback form. These infonnal assessments are used to revise the seminar content and strategies. Comments from preceding seminars are used as part of the introduction the following week. Thus, participants develope an awareness that their comments are read and how their input may affect future sessions.

Perhaps the most interesting comment that participants express is that they value the opportunity to talk to other faculty about teaching and problems they have encountered. A follow-up discussion of these comments indicates that their colleagues often talk about course or program content but rarely discuss teaching. They also remark, that since they are new to the university, they frequently feel uncomfortable going to a departmental chair or senior faculty member to openly discuss problems in the classroom.

Quantitative Assessment of the TTT Program

Quantitative assessments of the program suggest that the program enhances teaching effectiveness. Although this assessment does not constitute a true experimental study, it does provide insights into the program’s effectiveness.

The quantitative assessment is based on data collection related to the following question: “Are the mean test scores (as measured on the TTT student course appraisal instrument) of faculty in the control group significantly different from the mean test scores of faculty in the treatment group?”

Data collection required development of the TTT assessment instrument, establishment of control and treatment groups, and comparison of the differences between mean scores on a series of course appraisal questions. The TTT assessment instrument was developed by the program directors. Question selection was based upon intended program outcomes and a review of the teaching assessment literature. From the literature review the following instruments were found to include useful indicators of good teaching behaviors or student reactions to course planning and instruction: Instructor and Course Appraisal: Cafeteria System; IDEA Survey Form—Student Reactions to Instruction and Courses; Teaching Analysis By Students (TABS); Course Evaluation Booklet—Princeton University; University of Washington Survey of Student Opinion of Teaching; and Student Evaluation of Teaching—University of California at Davis.

From these instruments the Instructor and Course Appraisal: Cafeteria System from Purdue (1974) was selected to collect data on the two independent groups. Its selection was based upon the instrument’s flexibility and history at Ball State University. Its flexibility is derived from the over 200 items from which one can select in constructing an assessment instrument and its historical background includes established university norms based upon its use for over 20 years. Forty-five questions were selected for inclusion in the TTT assessment instrument. Item selection was based upon intended program outcomes and an analysis of the types and frequency of similar questions asked on instruments included in the literature review.

The control group included ten newly hired Ball State faculty who had not participated in the TTT program. The makeup of the control group was representative of those faculty who participated in the TTT program. Faculty were informed that the evaluation was not to replace any course evaluation instruments they were presently using and that the information would only be used to support the assessment of the TTT program and services.

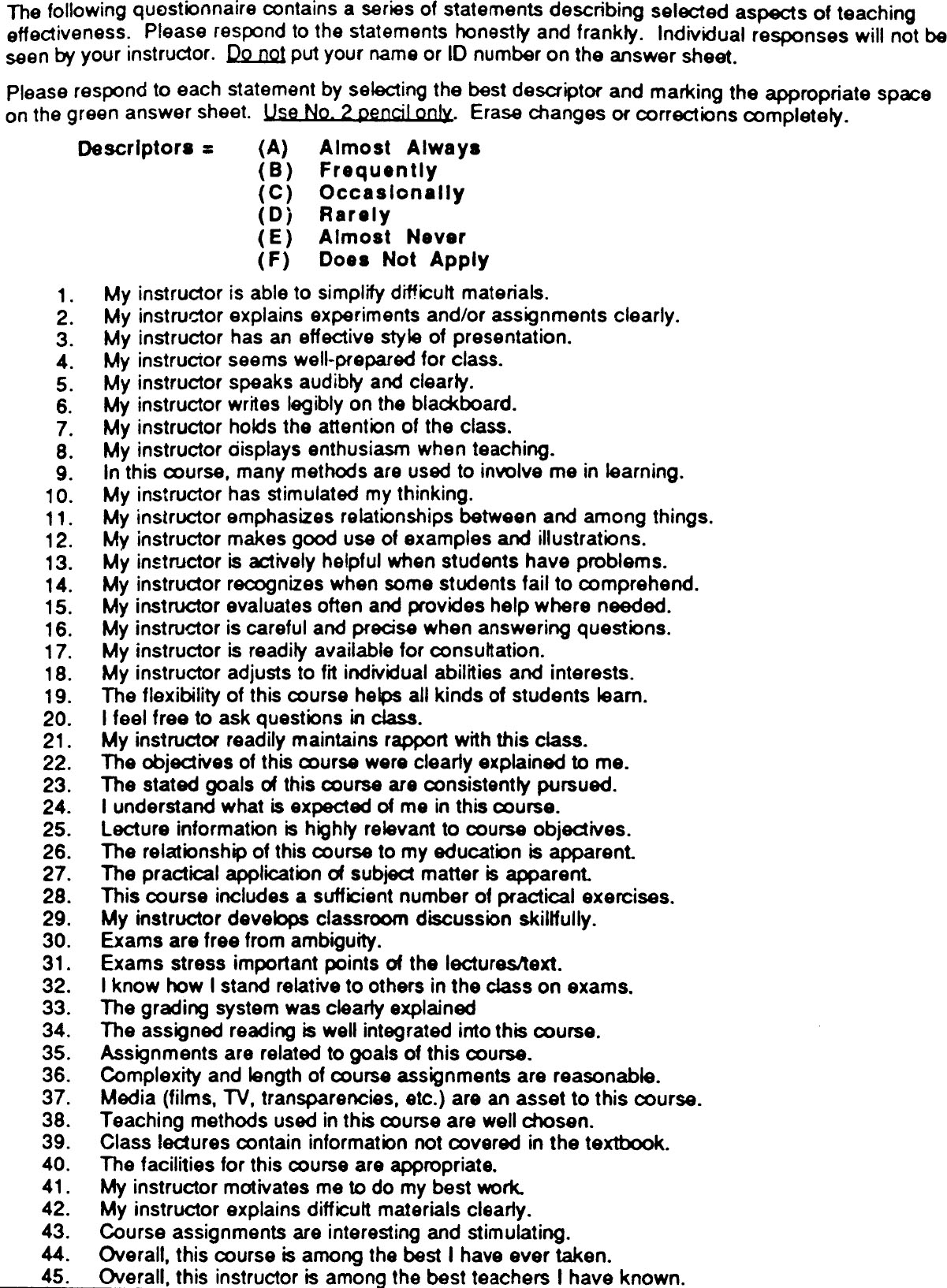

The TTT instrument, Figure 4, was administered during the 8th and 9th week of the Spring term. To insure that the scheduled date did not conflict with instructional activities, the proposed date and time were cleared through each instructor. At an agreed upon time, a trained research assistant went to each class and administered the assessment instrument to the students in attendance. Before the instrument was administered, students were informed of its purpose and that faculty would not see the results. While the instrument was being administered, faculty were asked to leave the room.

During the Spring of 1991, the treatment group was fonned from a group of randomly selected TTT participants. The TTT assessment instrument was administered to these fourteen TTT participants according to the guidelines established for the control group.

The data were analyzed using an independent “t” test. The independent “t” test was selected because: (a) the results of the study were to be projected to a population, (b) the dependent variables were measured on an interval scale, and (c) two independent samples were used in the study (Fraas, 1983). The analysis included a two-tailed probability level at the alpha level of .05.

A summary of the descriptive data gathered during the study and the results of the measure against the null hypotheses are shown in Table 1. The results illustrate the level of differences between the control and treatment groups for each question. The findings indicate that significant differences do exist between the control and treatment groups on many of the questions. A review of the data revealed that many of these questions are related to teacher behaviors such as: (a) providing students constructive feedback and assistance, (b) positively adapting to individual differences, (c) responding to students with respect and rapport, and (d) effectively using classroom discussion. It is also worthwhile to note that a large number of the items fell between the .05 and .1 levels (items marked by an “*” in the decision column).

FIGURE 4 Teaching the Technology of Teaching Program Assessment Form[1]Derived from Instructor and Course Appraisal: Cafeteria System (1974) — Purdue University Foundation.

FIGURE 4 Teaching the Technology of Teaching Program Assessment Form[1]Derived from Instructor and Course Appraisal: Cafeteria System (1974) — Purdue University Foundation.A large number of questions with significant differences at either the .05 or .1 levels were for items originally included in the instrument because they reflected the intended program outcomes. (Note: Questions that reflect intended program outcomes are indicated by a “+” sign in Table 1.) If the analysis were limited to the twenty-two program outcome questions, one finds that eleven of them are significant to the .05 level and five others at the .1 level.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Study

Qualitative and quantitative assessments show that participants value the TTT program and that it enhances their teaching. The quantitative study demonstrated statistically significant differences between the control and treatment groups on a number of items on the TTT assessment instrument. The study also revealed several positive trends on other items. Moreover, if the analysis had been limited to those items directly related to the planned program outcomes, the differences between the control and treatment groups would be positive. However, the writer can not say that the differences found in the quantitative assessment of the program can all be attributed to TTT. Fraas (1983) notes that even though differences between the control and treatment groups are shown to be significant, one must be careful not automatically to attribute the differences to the effectiveness of the treatment. This can be done only when the research has a high degree of internal validity. This does not mean that this research is invalid. Rather, its population is small, many variables are outside the researcher’s control, and that the assessment of the program was done only for the purpose of providing feedback for program revision.

But the evidence shows that the TTT program has a positive effect on teaching. The qualitative assessments and program growth indicate that faculty have a positive attitude toward the program and believe that it benefits them. These qualitative data (i.e., feedback forms, letters of support, and verbal comments) are very positive and supported by quantitative data.

| Item No. | Control Group | Treatment Group | Significance/Decision at .05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 1 | 3.882 | .608 | 4.359 | .408 | R |

| 2 | 3.889 | .567 | 4.269 | .385 | A* |

| +3 | 3.857 | .595 | 4.231 | .397 | A* |

| +4 | 4.376 | .433 | 4.550 | .337 | A |

| 5 | 4.538 | .350 | 4.745 | .180 | A |

| 6 | 4.258 | .404 | 4.324 | .637 | A* |

| +7 | 4.010 | .430 | 4.355 | .328 | R |

| +8 | 4.335 | .375 | 4.556 | .352 | A |

| +9 | 3.793 | .648 | 4.263 | .381 | R |

| +10 | 3.789 | .402 | 4.231 | .307 | R |

| 11 | 4.021 | .383 | 4.303 | .314 | A* |

| 12 | 4.102 | .361 | 4.295 | .356 | A |

| +13 | 4.278 | .349 | 4.514 | .297 | A* |

| 14 | 3.782 | .382 | 4.025 | .401 | A |

| +15 | 3.703 | .327 | 4.141 | .375 | R |

| +16 | 3.955 | .326 | 4.274 | .341 | R |

| +17 | 4.122 | .298 | 4.428 | .258 | R |

| +18 | 3.744 | .439 | 4.208 | .330 | R |

| +19 | 3.572 | .524 | 4.062 | .513 | R |

| +20 | 4.416 | .286 | 4.701 | .149 | R |

| +21 | 4.190 | .428 | 4.516 | .251 | R |

| +22 | 4.002 | .489 | 4.250 | .499 | A |

| 23 | 4.053 | .311 | 4.284 | .455 | A |

| +24 | 4.131 | .429 | 4.305 | .505 | A |

| 25 | 4.256 | .242 | 4.364 | .493 | A |

| 26 | 4.057 | .544 | 4.332 | .384 | A |

| 27 | 4.132 | .440 | 4.359 | .339 | A |

| 28 | 3.857 | .782 | 4.269 | .365 | A |

| +29 | 3.825 | .542 | 4.212 | .368 | R |

| +30 | 3.778 | .444 | 3.743 | .744 | A* |

| +31 | 4.257 | .181 | 4.277 | .716 | A |

| 32 | 3.594 | .527 | 3.790 | .395 | A |

| +33 | 3.877 | .445 | 4.241 | .583 | A |

| 34 | 3.871 | .435 | 4.084 | .416 | A |

| 35 | 4.225 | .380 | 4.388 | .425 | A |

| 36 | 3.926 | .428 | 4.050 | .569 | A* |

| +37 | 3.695 | .464 | 3.902 | .467 | A* |

| +38 | 3.803 | .484 | 4.198 | .451 | A* |

| 39 | 3.663 | .330 | 3.969 | .411 | A* |

| 40 | 4.263 | .257 | 4.281 | .308 | A |

| 41 | 3.803 | .452 | 4.143 | .401 | A* |

| 42 | 3.824 | .522 | 4.187 | .462 | A* |

| 43 | 3.577 | .464 | 3.948 | .453 | A* |

| 44 | 3.364 | .607 | 3.729 | .535 | A |

| 45 | 3.654 | .727 | 4.101 | .450 | A* |

SD = Standard Deviation R = Reject H0 A= Accept H0 + = Outcome Question * = .1 level | |||||

Recommendations for future study include: (a) comparing TTT participant scores on selected Cafeteria Instructor and Course Appraisal items with newly established university norms, (b) studying faculty attitudes towards the TTT program, and (c) assessing potential affects of the TTT program on faculty attitudes towards teaching. However, lacking these potential attitudinal studies, I will share just a few statements that participants have made about the program. In a letter written to the administration, a professor from the Management Science Department said:

Last semester, TTT was instrumental in my earning a teaching award — my first ever — which I proudly display in my office. I earned the award in spite of the fact that last semester was my first here at Ball State and that the classes I taught were entirely new to me.

The success of any faculty development program is determined by how many ideas are actually used in the classroom. An instructor from Nursing reported:

I have incorporated many of the seminar ideas into my classes. … more discussion and in-class, group participation activities with feedback. I have worked on the use of better media and instructional materials. . . allowed more time for thinking and answering. . . summarized at the end of class. I would recommend the TTT Program to anyone wishing to better their class presentations.

Twelve sessions require a significant time commitment on the faculty’s part, but one TTT participant said this about the program:

I was very thankful to have been chosen to take part in this program. It was a delightful learning experience and a super opportunity to be shared with other colleagues. Every Wednesday night a sense of exciting anticipation developed as to how I would be able to incorporate what was presented and discussed into my classes. I think BSU has a tremendous edge on being a fine teaching institution due to programs such as TTT.

Over the years, many of the TTT participants have evaluated the program in glowing terms. But some of the strongest recommendations come from university department heads, directors, and administrators. One such individual wrote: “I am greatly impressed with the TTT participants’ enthusiasm and dedication to good teaching. Participants credit the program … for the many good things that have come out of the seminars.”

Summary

This article has presented a description of the Teaching the Technology of Teaching program’s development, implementation, and assessment. Effective teaching requires an understanding of student needs and learning styles. Good teachers encourage students to think and be active participants in the learning process, and provide guidance and encouragement. TTT is a faculty development program designed to assist new faculty develop these characteristics and to become the best teachers they can be.

Findings of the program’s qualitative and quantitative assessment indicate that the program works. These findings indicate that statistically significant differences do exist between the control and treatment groups on several key questions, in particular, those questions involving teacher behaviors such as: (a) providing help and constructive feedback, (b) adapting to individual differences, (c) responding with respect and rapport, and (d) using classroom discussion. Qualitative data also show that faculty believe that the program is beneficial and designed to meet their needs.

Although the TTT program was specifically designed to reduce the problems often encountered by new faculty and enhance their teaching effectiveness, many teachers have commented that TTT would be an excellent program for all faculty.

References

- Berger, J. (1989, April 19). College teaching criticized. The Muncie Star, p. 22.

- Boice, R., & Turner, J. L. (1989). Experiences of new faculty. Journal of Staff, Program, & Organization Development,7(2), 51-57.

- Centra, J. A. (1972). Strategies for improving college teaching. Washington, D.C.: American Association for Higher Education.

- Chickering, W., & Gamson, Z. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. The Wingspread Journal,9(2), special insert.

- Fraas, J. (1983). Basic concepts in educational research. New York: University Press of America.

- Hamachek, D. (1969, February). Characteristics of good teachers and implications for teacher educators. Phi Delta Kappan,50(6) pp. 341-345.

- Hildebrand, M. (1973). The characteristics and skills of the effective professor. The Journal of Higher Education,44(1), pp. 41-50.

- Instructor and course appraisal: Cafeteria system. (1974). Purdue Research Foundation, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

- Kerwin, M. (1987). Teaching behaviors faculty want to develop. Journal of Staff, Program & Organizational Development,5(2), 69-72.

- Lembo, J. M. (1971). Why teachers fail, Columbus, Ohio: Merrill.

- McKeachie, W. (1986). Teaching tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher (8th ed). Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

- Mohan, M. & Hull, R. E. (1975). Teaching effectiveness: Its meaning, assessment, and improvement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

- Shackelford, R., & Henak, R. (1987). Teaching the technology of teaching faculty needs survey. Unpublished study, Ball State University, Muncie, IN.

- Shackelford, R., Seldin, P., & Annis, L. (1993). Lessons learned to improve teaching effectiveness. The Departmental Chair,3(3), 11-13.

- Turner, J. L., & Boice, R. (1987). Starting at the beginning: The concerns and needs of new faculty. To Improve the Academy, 6, 41-47.

NOTES

From To Improve the Academy: Resources for Student, Faculty, and Institutional Development, Vol. 7. Edited by J. Kurfiss, L. Hilsen, S. Kahn, M.D. Sorcinelli, and R. Tiberius. POD /New Forums Press, 1988.