The Medicine Wheel: Emotions and Connections in the Classroom

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

There was even more anticipatory energy than usual in my Black History class that late January day in 1991. We were about to discuss The Confessions of Nat Turner, a text that in the past had generated heated emotions as we debated whether students thought Turner’s 1831 slave revolt, in which 55 whites were killed, was ‘justified.” Among the 41 students in the course there were, as usual, about ten African-American students, two international students of color, and the predictable handful of sensitive white liberal students. But in contrast to past patterns, this year there was an unusually high number of whites who, following the political climate of recent years, blamed blacks for their claims of victimization and continuing anger, opposed affirmative action as “reverse discrimination,” wondered if slavery was all that bad, and selected examples from history to justify their view of the present (just like historians do). Most, however, whites and blacks alike, were confused and eager to learn.

As I put the question to the class, “Was Nat Turner’s revolt justified?,” I expected an even hotter expression of arguments than usual. To my surprise, although the discussion was emotionally charged, students did not divide along lines I had predicted. The resistant whites were overwhelmingly on the side of justifying the revolt, while the “white liberals” opposed it; the blacks were divided. It was not until the discussion was nearly over that I wondered if students had unwittingly chosen the side on Nat Turner that reflected their position on the recently-begun war in the Persian Gulf. A show of hands suggested that for many students strong feelings about violence and patriotism more than about slavery and Nat Turner lay behind their choices.

Emotions in the Classroom

This story confirms for me how powerfully students’ emotional investment in some current issue in their lives, either political or personal, affects their performance in class. Whether or not there is a particularly controversial topic to consider, emotions are always present in students’ degree of confidence in themselves as learners. A Chemistry colleague described to me (Frederick, 1990) how much energy his students displayed when he asked them on the first day of class to name the emotions they were feeling about taking Chemistry: “‘Fear,’ ‘frustration,’ ‘confusion,’ ‘anxiety,’ ‘panic’ … as fast as you can say those words, the students barked them out.”

Emotions are taboo in higher education. The paradigm that governs how we are supposed to know and learn is rational, logical, empirical, analytic, competitive, and objective. Students learn to distance themselves from that which they are supposed to know. In this familiar model the assumption is that classrooms are isolated castles, surrounded by icy moats signaling all who enter to abandon feelings and prepare for the rigors of empirical investigation and rational discourse. Even those of us in faculty development do much less work with Bloom’s affective than his cognitive domain; we do not emphasize “critical feeling” nor do workshops on “emotions across the curriculum.” And for good reason: our colleagues would shun such efforts, in part because of academic socialization into the rational model and in part because they fear their inability to handle emotional realities in the classroom. A Philosophy professor told me recently that, after some of her students burst into tears during a discussion of ethical questions about euthanasia, “I gave up ethics for logic courses.”

In a little-known but wonderful book by Parker Palmer (1983), To Know As We Are Known: A Spirituality of Education, Palmer writes that ‘‘teachers must … create emotional space in the classroom, space that allows feelings to arise and be dealt with” (p. 83). With Palmer, I believe it is time to take seriously the role emotions play in teaching and learning, and to begin addressing ways not only of creating emotional spaces for learning, but also of using affect to make connections between the realities of our students’ worlds and the important intellectual constructs of our courses. At the 1989 meeting of the International Society for Exploring Teaching Alternatives, A. Miller predicted that “emotions will be the new frontier in learning” and S. BeMiller (1990) agreed, saying that the growing faculty interest in such areas as cooperative learning, student motivation, and small group active learning was an indication that emotions “may well be the flagship idea for the future of education.”

We delude ourselves if we think that emotions do not already exist in our classrooms. As we seek to explain differential equations, or the causes of the American Revolution, or evolution, or a Tillie Olsen short story, or the sonata-allegro form, or attribution theory, no matter how skillfully, many of our students are sitting there with anxiety, fear, joy, shame, anger, boredom, or excitement. Tony Grasha’s (1990) study of student-reported emotions describing ineffective courses included “bored,” “frustrated,” “angry,” and “sad.” In effective courses they felt “excited,” “happy,” “exhausted,” and “confident.” Significantly, in Grasha’s study students listed “stressed” or “stressful” under both, suggesting that tension or, in Piaget’s terms, “disequilibrium,” has high emotional power and works both for and against learning.

Teaching is, of course, as much socially constructed as anything else, and is inherently manipulative. Do we not stifle students’ creativity and render them voiceless when we insist that they always “back up” their arguments, as we say, with concrete examples and evidence? Do we not often paralyze some students when, as in “paper-chase,” we ask a question and then direct a particular student to answer? Often, a student does in fact know the right response, but fearful emotions block the effort. Feelings of fear, especially of exposed ignorance, failure, and damaged self-esteem, according to Palmer (1983), are “major barriers” to learning and can cause students to “close down.” Which of us has not seen that unmistakeable look, somewhere between terror and embarrassment, that passes across students’ faces when confronted with a question they cannot, on the spot, answer, or when they cannot find the right words to express themselves on an issue? At its worst, we risk killing motivation to learn altogether.

By acknowledging the presence of emotions in the classroom, especially student fears (and even our own), we can create the kind of accepting atmosphere that frees students, even in fumbling ways, to explore what they think and feel about a question, text, or issue. In a classroom space where students are encouraged to express their feelings as well as half-formed ideas, knowing that others will respect and build on them, they not only move toward community-based agreement on truth, but also develop more confidence in themselves as learners. We encourage and work with students to write fluently, to think critically, to reason logically, and to compute correctly. Why should we not, in addition, urge them to feel authentically? The most promising way of doing that is to connect their lives to our courses.

Connections in the Classroom

It is no accident that the movement to enhance the quality of teaching and learning has coincided almost exactly with the increasing presence of women in higher education and with the emergence of a new paradigm for knowing and teaching. This model, which many male as well as female teachers exemplify, extends the findings and principles of innumerable recent works and reports on higher education and how students learn, all of which stress the importance of active, involved, connected, and collaborative learning.

This new model of knowing and teaching is seen in the writing and work of Palmer (1983, 1989) and Lee Shulman (1989), but especially in Elizabeth Minnich’s Transforming Knowledge (1991) and in Women’s Ways of Knowing (1986) by Mary Field Belenky, Blythe McVicker Clinchy, Nancy Rule Goldberger, and Jill Mattuck Tarule. The latter is a much-criticized, but I think vital, book about teaching and learning, applicable to both women and men. Rather than focusing, as in the old model, on rational analysis, objectivity, critical distance, and competitive learning, the new epistemology-pedagogy affirms intuition, synthesis, empathy, subjectivity, and collaboration. It is holistic rather than fragmented and speaks in the language of matrices and webs rather than linearity and discrete (“hard facts”) pieces of evidence. Above all, the key new concept in learning is “connections,” in which teachers help students, as Palmer (1990) puts it, see how to “connect self and subject,” “knowledge and autobiography” (p. 14). The authors of Women’s Ways of Knowing call it “connected teaching” when teacher/student “roles merge,” learners work in collaborative groups that “welcome diversity of opinion,” and truths emerge as a result of discussions in which “it is assumed that evolving thought will be tentative [and] no one apologizes for uncertainty.” Connected teachers are like “midwives,” helping students “in giving birth to their own ideas” and drawing out “the truth inside” (1986, pp. 217-23).

To call forth what is inside is an inherently emotional process. To do so requires faculty not only to be more aware of their own internal emotional processes, but also to know more about who their students are holistically, what they already know, and how they learn. Surely half of what constitutes effective teaching is faculty expertise and enthusiasm for the content of our courses. But the other half, according to the new paradigm, is to find ways of connecting our key course concepts and essential learning goals with what we can learn about our students, their voices, their values, their inner worlds, their passions and, most significantly, their considerable experience (including both prior knowledge and misconceptions) with the course material they join us to learn. We must, then, as William Perry and others have been telling us, learn to listen to our students’ many voices in order to connect their expriences with our material.

Lee Shulman (1989) made the idea of connection concrete in his address at the 1989 National AAHE Conference. Drawing pedagogical lessons from Jaime Escalante’s extraordinary success teaching AP calculus in the barrios of East Los Angeles, Shulman wrote that the key to effective learning, indeed “the most significant area of progress in cognitive psychology in the last ten years,” is precisely this process of connection. The teacher, he wrote, “must connect with what students already know and come up with a set of pedagogical representations, metaphors, analogies, examples, stories, demonstrations, that will connect with those prior understandings, that will make them visible, will correct them when they are off base, and will help the students generate, create, construct, their own representations to replace them” (p. 10).

Shulman’s representational example was Escalante in Stand and Deliver, using the image of digging a hole in the sand with the excavated pile next to it to illustrate the crucial principle of negative numbers: “plus two, minus two, what do you get?” I have found success invoking images of student living unit situations to illustrate dealing with historical group conflict, and of parent-children conflicts in helping students understand the struggle for independence and self-rule in the American Revolution. Nothing is more important in engaging and motivating students, I believe, than discovering and using metaphors and images that connect developmental issues such as autonomy, individuation, and intimacy with the concepts we are teaching.

Although partly cognitive, the use of representational imagery is a highly affective process. Carl Jung (1971, 1984) suggested that emotions are in fact the connective link between the learner and course content: “feeling is primarily a process that takes place between the ego and a given content … that imparts to the content a definite value in the sense of acceptance or rejection.” In this judgment process, in deciding whether to “like” or “dislike” an idea (that is, in imagining one’s own autonomy issues with parents as a way of understanding the American Revolution), it is precisely “the feeling function” that for Jung “connects both the subject to the object … and the object to the subject” (pp. 89-90). It is feelings, then, that can bring together, or heal, the separation of knower and known in the objective paradigm. As Parker Palmer (1983) wrote, only “spirituality of education,” an affective notion, “might yield a knowledge that can heal, not wound, the world” (p. 6).

The purpose of using emotions in the classroom, in sum, though defensible in helping students develop awarenesses and confidence in the affective realm for its own sake, also serves to facilitate student insights about conventional learning goals. Teaching to emotions is motivational. It focuses student attention, arouses interest, connects the student’s world to ours, and builds a classroom community. Moreover, emotions trigger memories and code experience, thereby serving as retrieval cues for retention. Emotional experience in the classroom leads to cognitive insight: affect deepens understanding. How to evoke these emotions pedagogically takes us into the Medicine Wheel.

The Medicine Wheel in the Classroom

Four years ago, I twice visited Sinte Gleska College, a Lakota tribally-run institution on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, to work with the faculty on facilitating student participation in class discussions. I gained far more than I gave. Other than first hearing the Lakota (and Confucian) saying on how students learn—“Tell me, and I’ll listen/Show me, and I’ll understand/Involve me, and I’ll learn”—I discovered a book, The Sacred Tree (1984), created by the Four Worlds Development Project at the University of Lethbridge in Canada and used in Sinte Gleska freshmen writing courses.

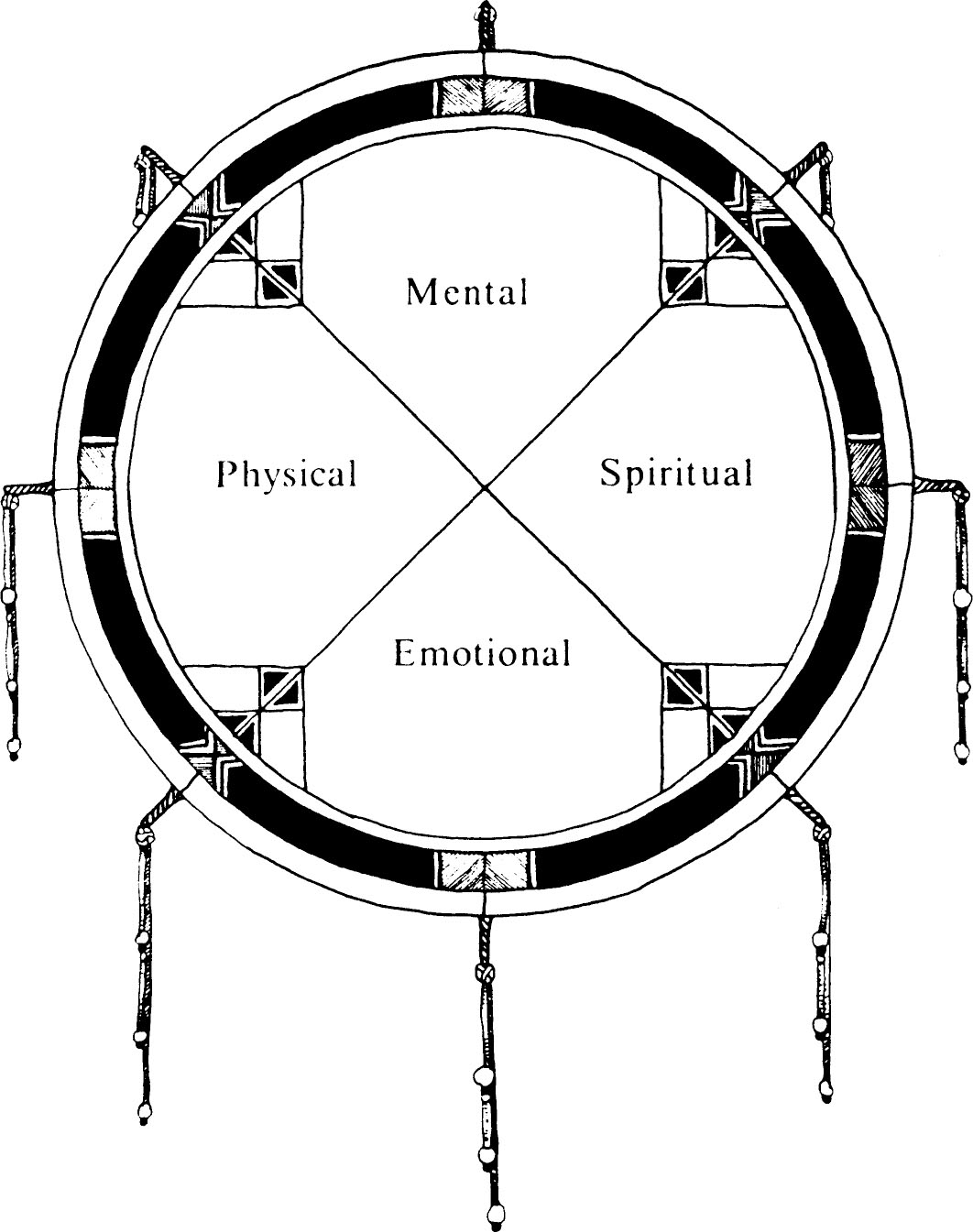

In this book is a representational model, the Medicine Wheel [see Figure 1], an ancient symbol of the North American Indians that depicts in one powerful image the sacredness of the circle to Native American life and the interconnectedness of various aspects of life expressed in four quadrants. Four is a sacred number for many American Indian groups: the four directions, each with its own meaning and gifts [See Appendix A] the four basic elements of the universe, the four races, the four (Lakota) cardinal virtues. Most importantly for us, the Medicine Wheel also represents a holistic approach to four dimensions of learning: mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual.

The Medicine Wheel corresponds exactly with an early and fundamental idea in Jung, “the fourfold structure of the psyche,” which, according to von Franz and Hillman (1971, 1984), he “found confirmation of … everywhere in myths and religious symbolism” (p. 2). Note also that this fourfold model coincides with two of the polarity indices of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator: thinking and feeling and sensation and intuition. Not incidentally, I believe, the “cycle of learning” in both David Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory and the Gestalt therapeutic learning theory of figure/ground, contact, awareness and resolution (or closure) follow this same circular representational model.

In the many workshops I have led around the country in recent years, nothing arouses more faculty (or student) interest than the Medicine Wheel. Faculty instantly recognize that we spend much of our time teaching primarily to one-quarter of our students’ learning potential. In the pedagogical implications of the Medicine Wheel we can find many strategies for focusing on the long-ignored emotional and spiritual aspects of student learning. The remainder of this article will briefly describe some of the strategies implied by the Medicine Wheel. With the imagination of creative teachers and faculty developers, the possibilities are limitless. The following are a few of mine.

FIGURE 1 The Medicine WheelCopyright© 1984. Reprinted by permission of Four Worlds Development Project, University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

FIGURE 1 The Medicine WheelCopyright© 1984. Reprinted by permission of Four Worlds Development Project, University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.The first, quite simply, is to introduce students to the Medicine Wheel, and to suggest that they keep the four dimensions in mind as they read a text, confront a problem, or are introduced to a new concept or skill. Follow up by using the Medicine Wheel to structure the discussion. One can enter the Wheel in any quadrant and then move to the others. For example, when beginning the discussion of a text—any “text”—we could ask students to be concrete in dealing with the physicality of the reading, visual or material object, or experience. Invite them to recall vivid scenes or moments from the text using all their senses: “What do you see, hear, feel, smell?” Discussions “go better” (by which I mean more students are more engaged with the text and discussion) when we begin with concrete images and move then to the themes and patterns that emerge from the concreteness. We could, however, begin, as we most often do, at the cognitive mental level or, as a group, we could derive themes, patterns, and issues from a list of concrete physical images.

I have found that for many texts and topics, whether a book, poem, or artifact, a case study, an experience, or a quantitative problem set or laboratory experiment, it is useful to begin in the South, with emotions. Faculty members regularly report in both workshops and private conversations, especially when invited to describe successful classes, how students’ motivation, engagement, energy levels, and even their bowed heads are raised whenever the topic shifts to personal issues they connect with on an emotional level. These invariably involve life stage, developmental, values, and relationships issues, and nearly anything autobiographical. Therefore, where possible, suggest connections between these issues and the particular idea or concept at hand, and begin with affective questions: “What were your feelings doing this assignment? Reading this text? Doing this experiment?” “How does this text/issue/problem relate to your life?” As a follow-up to generating a list of emotional reactions, ask what specific moment in the text or topic triggered particular feelings, and then move Northward, from “words, images and feelings” (emotive-intuitive) to “themes, issues, and patterns” (mental-intellectual).

Story-telling is an almost ideal strategy for illustrating the interconnectedness of the four quadrants of the Medicine Wheel, especially the relationship between feeling and thinking. Asking students to tell stories connects their lives with course content (“self and subject”) and affirms their prior experiences with the themes and issues of the course: ‘‘Tell a story about a successful experience with math, or some quantitative problem,” or “with an artistic project,” or “as a leader,” or “when dealing with a social science policy issue,” or ‘‘when you needed to reconstruct the past in order to deal with the present,” or ‘‘with understanding a natural phenomenon,” or ‘‘with a religious concern.” There is, in fact, no course or discipline with which students have not had some prior experience or feelings, including their apprehensions and eager anticipations entering a new course.

By asking students to tell a success story, or perhaps an illustrative “failure” they learned from, in some combination of writing and orally in small groups, the teacher puts them in touch with themselves at their most confident best, empowered to reflect on ways in which their lives matter in terms of the course. Telling stories not only affirms students’ experiences and voices, but also validates different student voices. From narratives the class hears about the experiences and learns to value the diversity of multicultural voices in the class, women as well as men, black as well as white, rural as well as suburban or urban. Stories, moreover, are an excellent way to build community and trust in a class as well as for teachers to learn who their students are.

In writing and telling their narratives, and in listening to others, I suggest to students that they pay attention to details that would give the story more concreteness and context, as well as to note emotionally laden key words and metaphors we all use when telling a story. In debriefing, or making the transition from student stories to course themes, ask students, again in small groups or as a whole class, to focus on the single moment in their narrative that had the most emotional (or spiritual, or physical) power for them. Listen to a few and write the power images and words on the board. Then step back and ask the class what themes, patterns, and issues they see in these central images from the stories. In this way, we move from South to North in the Medicine Wheel. Furthermore, in this way we humanize and particularize the connections between student lives and the themes of a course.

The Medicine Wheel, then, suggests various ways of connecting autobiographical experiences, emotional responses, and affective imagery on the one hand with cognitive concreteness, rational observations, and reflective critical thinking on the other. The Wheel also suggests the pedagogical power, rooted in cognitive dissonance and disequilibrium theory, of challenging students· normal learning patterns. For example, present students with any anomaly, puzzle, psychic phenomenon, or dissonant image that defies conventional explanations and ask them to solve or interpret the problem: a mathematical word puzzle, numbers that do not “compute,” a visual image with several conflicting symbols in it, an “out-of-body” spiritual experience, or a multi-media presentation with inspiring music and depressing visuals. To deal with the dissonance, students will use the full developmental potential of the Medicine Wheel: disequilibrium invariably evokes affect as well as the consideration of both intuitive and empirical explanations.

A variation is to invite students to reverse their normally expected modes of learning. For example, many teachers of quantitative subjects (Mathematics, Economics, Statistics, and Computer Science) have had much success in asking students to write narrative or autobiographical stories about the process of how they go about solving or working their way through a problem. Some suggest constructing a dialogue with oneself, explaining each step of the proof. This exercise in metacognition, which is applicable in any discipline, teaches students how they learn while actually in the process of learning.

In verbal, narrative fields, switch students from words, or conventional verbal language, to art or mathematical symbolism. One day, while teaching a particularly difficult text on American Indian religion and, disappointed with our collective ability to state the thesis of the book, I asked students to “Draw it! Draw a picture of the thesis.” After a few moments of puzzled looks, they went to work. The results were startling and far more successful in beginning to understand Indian religion than the verbal sentences we had been struggling to construct. Although several students created rather linear drawings, many others were able to conceive symbolic and metaphorical images (a lot of circles and interconnected webs, some pictographs, and sacred trees) that captured the essence of the world view far better than we had verbally. In fact, they were beginning, in a rudimentary form, to understand what “thinking Indian” might mean.

In a second example, I recently taught a chapter on the complex psychosexual patterns of “The Woman in Love” from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. The discussion would be difficult, I figured, not only because the text was difficult, but also because of my students’ own struggles with intimacy and relationships. In order to get safely into the text I asked them to choose from among several options what they thought was the appropriate mathematical equation for love and relationships. Among the choices were 1/2 + 1/2 = 1; 1 + 1 = 2; 1 + 1 = 3; 1 + 1 = 1. As we explored the implications of these possibilities (against the background of having two days earlier discussed Henrik Ibsen’s The Doll’s House [“1 + 0 = l,” they said]), the students were able to see the danger of relationships built upon non-whole persons and understood both de Beauvoir and Ibsen better. They concluded that since the developmental outcome of Nora’s leaving was in doubt, as was the “miracle” of whether Torvald would change, the “right” equation was x + y = z, a possibility I had never considered. Because these were issues of immediate concern, they were deeply connected with the discussion; the use of mathematical symbols gave them an indirect means of discussing a vulnerable topic.

There are, of course, many other strategies that help students connect the various emotional, spiritual, mental, and physical quadrants of the Medicine Wheel with course themes and their own lives. Among them are role-playing, case studies, and debates. Each of these strategies involves students mentally (by choosing sides or adopting a role, and by having to articulate arguments and a particular role or position); physically (by actively moving to one’s chosen position); and emotionally (by interacting with others both competitively and collaboratively). If the case or role involves issues that connect with the student personally (relationships, values, life stage issues), then the experience can be spiritual as well.

Two strategies that are particularly moving spiritually, while respecting each student’s private definition of a higher power, are meditative exercises and guided imagery. The meditation can be accomplished through free writing, journaling, or quiet reflection: going within oneself to meditate on a topic, issue, experience, or personal strength. In guided imagery the teacher gently steers students through an imagined situation appropriate to a course topic. Or, in practicing a skill, the student can, like a high jumper or diver, “image the steps” to the successful completion of a task. Guided design is particularly powerful in taking students through the experiences of someone not them, either culturally or sexually, as a way of crossing cultural, gender, geographical, and even historical barriers. I have also used a combination guided meditation at the beginning of class simply to help us all become fully present in the classroom and to center our thoughts on the texts and topics ahead. The emotional and spiritual impact of such experiences can be heightened by playing appropriate music softly in the background.

Music or an eloquent orator, especially when paired with visual imagery, either in a random collage or closely synchronized, has the potential to evoke powerful emotions and thereby arouse intense student attention and interest. Imagine walking into a History or Speech Communication class hearing a Martin Luther King or Winston Churchill speech, with relevant slides flashing on the screen. Or into an Astronomy class to the music of Holst’s ‘The Planets,” or into Geography or Soil Agronomy to the “Pastoral Symphony,” or into a social science course greeted by any number of popular songs, or raps, whose lyrics speak to contemporary political, sociological, or economic issues. Although easier in some disciplines than others, there is no course for which, with a little imagination and a lot of help from students themselves, there is not an appropriate piece of music that can be combined with visual images to evoke the full range of learning potential suggested by the Medicine Wheel.

When I show a series of visual images accompanied by an appropriate musical piece or speech, I prepare students ahead of time by asking them to consider “words, images, and feelings” during the experience and then give them a moment or two after the presentation to write them down and then to talk briefly with someone sitting near them. Then, I invite students to call out the words, images, and feelings evoked by the music and visuals; I write them down on the board as I hear them. As in any brainstorming exercise it is essential that the teacher write down exactly what the students say and not change their language.

Once the board, or a transparency, has been filled by their responses, I sit down in the midst of the class and, with them, look at the list and ask, “What patterns, themes, or issues do we see?” The center and focus of the class thus becomes their experiences and their language. In this way, with a well-chosen set of slides and piece of music, we have established the key integrating themes of a course, sub-unit of a course, or single topic. We have also used the full developmental learning potential of the Medicine Wheel.

Of course, there are dangers in using these strategies. Music and visual imagery evoke deep feelings and possibly disturbing recollections. Role-playing and debates generate heated arguments. Connecting the important issues we teach to student lives often touches sensitive chords. Like the ethics-turned-logic professor, faculty understandably worry that an intense emotional discussion might trigger an outburst from an unstable student or unleash tides of irrationality they feel uncomfortable dealing with. We are concerned, I think appropriately,about infringing on students’ personal space and freedom (though rarely do we raise that issue in calling on a student to recite in class or perform mentally). We may be worried, above all, over “What to do if it works?” What if students are exploring, say, gender or racial issues and really begin to engage each other in multicultural or male/female differences of experience and perspective? I know that worries many teachers, who are understandably concerned about control and would prefer to avoid such conversations. But such dialogue is indispensable in preparing our students for life in this changing and diverse culture.

At the 1991 AAHE Conference in Washington, Elie Wiesel (1991) said that the most effective way of “educating against hatred” was precisely to “study together” and to learn to listen to and be “sensitive to” the pains, hopes, ideas, and ambitions of others. This happens best when students engage each other and texts in what AAHE planners termed “difficult dialogues.” As Wiesel said, “if a student can respond to a text, he can be moved by a brother or sister.” In an era in which higher education is experiencing a serious backlash against efforts to be more inclusive of and sensitive to all peoples and cultures, we cannot let our fears deter us from facilitating these kinds of conversations among our students.

I do not take the fears lightly, and there are actually many things we can do to facilitate the somewhat orderly exchange of “difficult dialogues” and emotions in class. First, we can name, or acknowledge the tensions and agree on some clear boundaries for legitimate behavior. Second, if a particularly heated or inappropriate moment is reached in a discussion, we can always call “time out” and ask students to go into themselves to reflect and write about what has been happening, and then to resume the discussion. Third, when emerging from an emotional experience following a heated discussion, meditation, or music/images presentation, we can suggest to students the importance of spending the first few moments alone with their thoughts and feelings, then making eye contact with someone else and talking together, and finally debriefing as a whole group.

Fourth, and fundamentally, we can trust our students’ capacity for restraint and respect, even in the midst of heated disagreements. Groups have a remarkable, even mystical capacity for self-correction. Ultimately, we need to look within at our own risk-taking fears. Arousing feelings in class raises issues of power and control that bring us face to face with ourselves. Perhaps we will see ourselves—consistent with the holistic imagery of the Medicine Wheel—as imperfect, perhaps a little bit insecure, but nonetheless thoroughly lovable and spiritually-valued human beings.

My friend, Nan Nowik, who was as innovatively courageous a teacher as she was in facing her losing battle against cancer, was an expert on reticent students. At Denison University, where she taught American literature and women’s studies, and in her work with faculty from the other eleven colleges of the Great Lakes Colleges Association (GLCA), Nan helped hundreds of students deal with their “terror” of speaking in class. At her last GLCA summer teaching workshop, which we did together for ten years, Nan was even more eloquent than usual in sensitizing teachers to the fears and needs of reticent students. She suggested that many professors had themselves once been “reticents,” and invited those so self-defined to talk further. Two-thirds of the participants, most of them men, joined her.

Students and professors are not so different. Just below the surface of a faculty member’s polished professionalism in front of a class of nineteen-year-olds is a struggle, perhaps with his own teen-ager or her own patriarchal department chair. Behind the student’s question about “what you wanted on this paper,” as she or he appears at our office door, is often a deeper personal question: “Do you like me?” “Am I any good?” “Will I make it?” But these are our questions too. Unspoken but common to both teachers and students are issues of self-esteem, self-confidence, and autonomy. Each is, in part, deeply emotional.

It is fitting that before she died Nan was working on Louise Erdrich and American Indian women’s literature. Nan understood the holistic meaning of the Medicine Wheel and taught us that the emotional terror of a reticent student was a barrier to cognitive learning. She acknowledged the power of feelings and asked both students and herself to risk a little to empower themselves. Like Nan Nowik, we, too, might dare to risk in order to discover the power of emotions to connect our students’ lives with our courses and thereby to expand their full capacity to learn.

References

- Belenky, M. F., McVicker Clinchy, B., Rule Goldberger, N., & Mattuck Tarule, J. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. New York: Basic Books.

- BeMiller, S. G. (1990). Previewing ISETA ‘90, a summary of the Proceedings of the 20th conference of the international society for exploring teaching alternatives in 1989. Connexions, 3(2).

- Four Worlds Development Project (1984), The sacred tree. Alberta, Canada: Four Worlds Development Press.

- Frederick, P. (1990, December). The power of story. AAHE Bulletin, 3, 5-8.

- Grasha, T. (1990). Using traditional versus naturalistic approaches to assessing learning styles in college teaching, Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 1(1), 23-38.

- Palmer, P. (1990). Good teaching: A matter of living the mystery. Change, 22(1), 11-16.

- Palmer, P. (1983). To know as we are known: A spirituality of education. New York: Harper & Row.

- Shulman, L. S. (1989, June). Toward a pedagogy of substance. AAHE Bulletin, 8-13.

- von Franz, M., & J. Hillman. (1971, 1984). Lectures on Jung’s typology. New York: Spring Publications.

- Wiesel, E. (1991, June). Education against hatred: A conversation With Elie Wiesel. AAHE Bulletin, 9-10.

Appendix A

Summary Chart, The Gifts of the Four Directions

East

—light —beginnings —renewal —innocence —guilelessness —spontaneity —joy —capacity to believe in the unseen —warmth of spirit —purity —trust —hope —uncritical acceptance of others —love that doesn’t question others and doesn’t know itself —courage —truthfulness —birth —rebirth —childhood —illumination —guidance —leadership | —beautiful speech —vulnerability —ability to see clearly through complex situations —watching over others —guiding others —seeing situations in perspective —hope for the people —trust in your own vision —ability to focus attention on present time tasks —concentration —devotion to the serivce of others |

South

—youth —fullness —summer —the heart —generosity —sensitivity to the feelings of others —loyalty —noble passions —love (of one person for another) —balanced development of the physical body —physical discipline —control of appetites —determination —goal setting —training senses such as sight, hearing, taste —musical development —gracefulness —appreciation of the arts —discrimination in sight, hearing and taste —passionate involvement in the world | —idealism —emotional attraction to good and repulsion to bad —compassion —kindness —anger at injustice —repulsion by senseless violence —feelings refined, developed, controlled —ability to express hurt and other bad feelings —ability to express joy and good feelings —ability to set aside strong feelings in order to serve others |

West

—darkness —the unknown —going within —dreams —deep inner thoughts —testing of the will —perseverance —stick-to-it-iveness —consolidating of personal power —management of power —spiritual insight —daily prayer —meditation —fasting —reflection —contemplation —silence —being alone with one’s self —respect for elders —respect for the spiritual struggles of others —respect for others’ beliefs | —awareness of our spiritual nature —sacrifice —humility —love for the Creator —commitment to the path of personal development —commitment to universal life values and a high moral code —commitment to struggle to assist the development of the people —ceremony —clear self-knowledge —vision (a sense of possibilities and potentialities) |

North

—elders —wisdom —thinking —analyzing —understanding —speculating —calculation —prediction —organizing —categorizing —discriminating —criticizing —problem solving —imagining —interpreting —integrating all intellectual capacities —completion —fulfillment —lessons of things that end —capacity to finish what we begin —detachment —freedom from fear | —freedom from hate —freedom from love —freedom from knowledge —seeing how all things fit together —insight —intuition made conscious —sense of how to live a balanced life —capacity to dwell in the center of things, to see and take the middle way —moderation —justice |