Intervention: Moving University Units Toward Organizational Effectiveness

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

One paradox facing higher education today is the growing literature on organizational change and development and the small number of reports and studies discussing specific cases and applications in various colleges and universities. To add to the problem, recent factors directly affecting academic departments appear to be contributing to an increase in inter- and intra-departmental conflicts. Although there is material available on conflict in organizations, few attempts have been made to describe the management of such conflicts in academia in ways that improve the organizational effectiveness of departments. Practitioners who are effective as consultants often do not take the time to explore the validity and effectiveness of their procedures. In the same vein, departments that address and surmount major problems often don’t share their successful processes with other campus units.

This study presents one of our actual interventions with an academic department in conflict in order to illustrate processes that we have found useful for unit improvement. An overview of our assumptions regarding organizational health and development precedes the case study. We also briefly discuss a variety of other interventions that we have employed with different departments.

Background

In a more extensive study, we have made some preliminary assessments as to major contributors to conflict in academic units in a variety of institutions, and have described the interventions which were applied. These conclusions were drawn on the basis of more than twenty organizational development interventions that we have with academic sub-units in various colleges and universities in California and Hawaii. The typical approach was a short-term intensive intervention, although some departments were in the process of consultation over a period of five to six months. Data were gathered at the time of the intervention and as a follow-up one tofour years later. Data sources included questionnaires six months or more after the intervention and follow-up interviews with key participants, as well as written evaluations collected at the end of the original sessions. One or both authors served as consultants to each of the units in the study.

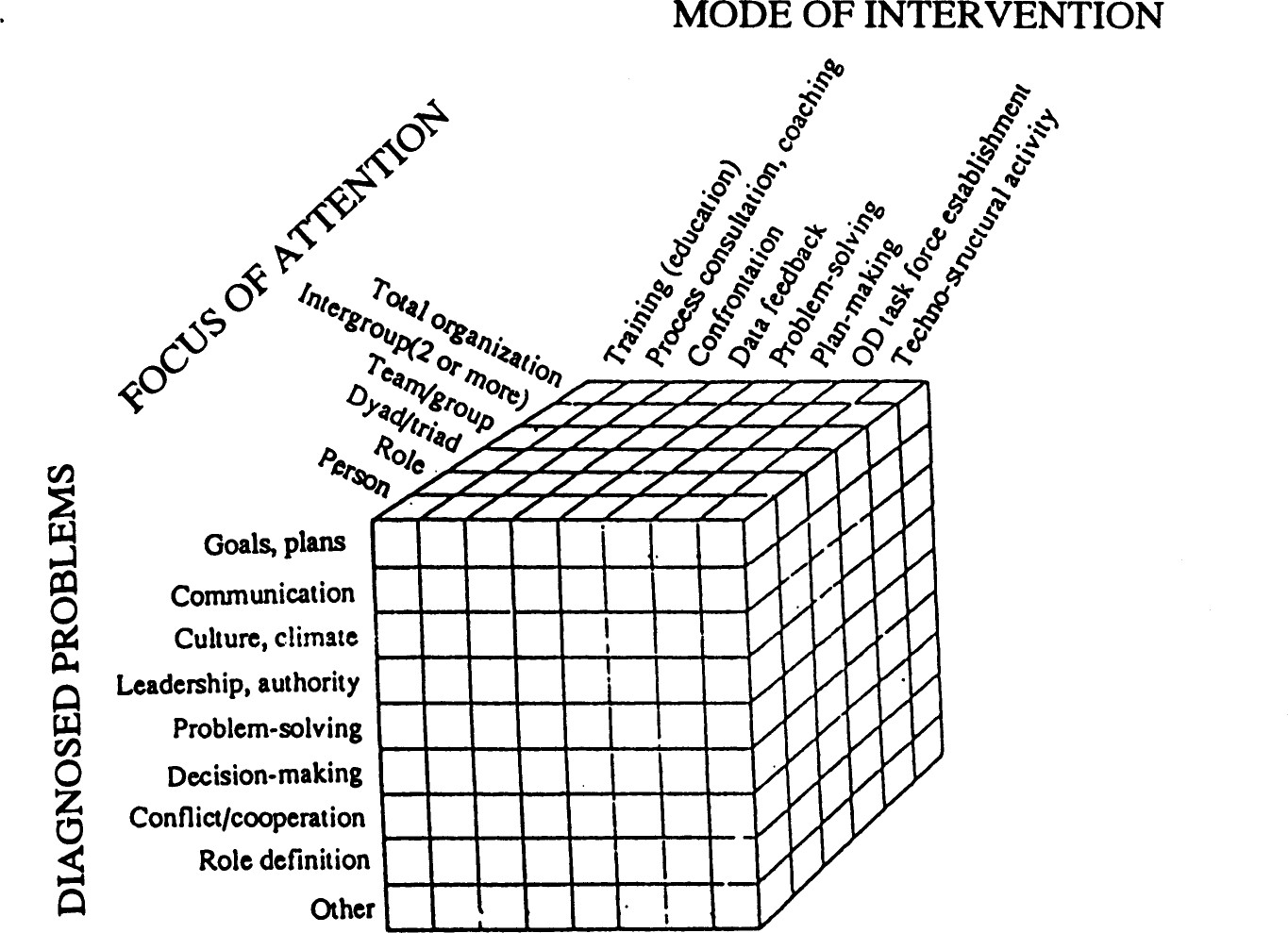

Consistent with the Organizational Development Cube (Figure A, Schmuck and Miles), the interventions that we employed included data feedback, problem solving, and plan making. The diagnosed problem in most situations was that of conflict/cooperation. Related to the conflict were often problems in role definition of the department chair and concomitant problems of decision making.

Intervention is defined by Chris Argyris as “the activity of helping individuals, groups, and organizations solve problems, especially those that require double-loop learning.” By double-loop learning, Argyris means achieving intentions or correcting an error and also re-examining the underlying values. ( Reasoning, learning, and Action by Chris Argyris, Jossey-Bass, S.F.,1982, p. xix)

We have not been involved in rigidly controlled research procedures; rather, our study grew out of our attempt to gather information about the effectiveness of our interventions as consultants over the past ten years. A primary focus of the interventions in all our cases was the maximizing of valid information within the work group. In addition, there was an attempt in each case to involve the group directly and indirectly in the collection of data so that it became their data. Ownership appears to be a key to the serious and effective use of data for improving the sub-unit of the institution.

Figure A The OD Cube: A scheme for Classifying OD InterventionsFrom Organization Development in Schools by Richard A. Schmuck and Matthew B.Miles.

Figure A The OD Cube: A scheme for Classifying OD InterventionsFrom Organization Development in Schools by Richard A. Schmuck and Matthew B.Miles.Theoretical Underpinnings

In attempting to find a thread of commonality among the causes of conflicts in departments, it appears to us that trust, or lack of it, is the most consistent aspect of departmental health. This fact led us to explore Jack Gibb’s TORI theory of personal and organizational development; the acronym stands for four processes which Gibb describes as essential for a healthy, productive person or organization: trust, openness, realization, and interdependence. Each of these processes addresses an area in the life of an organization that affects its ability to evolve and function more fully.

Trust is critical for long-term effectiveness and the most efficient use of human and other resources. Although some organizations seem to be productive and at the same time exhibit distrust between the different levels in the organization and across each level, this distrust drains away energy and creates dysfunction. These organizations are productive in spite of their handicap, not because of it; therefore, they fall short of their potential for accomplishment.

Openness is also essential for a fully functioning organization. Communication channels must be free of barriers, feedback loops must be created and used, and care must be taken to continually gather data and pass on vital information to appropriate parties.

Realization of the mission and uniqueness of an organization, valuing that uniqueness, and focusing resources in support of the primary mission are also essential parts of organizational health. Clarifying the question, “What is this group really about?” simplifies the task and the structure.

Interdependence, the development of a cohesive team or community, is the last process singled out as critical to organizational health. Acknowledging what each employee has to give and the support each one needs to perform necessary responsibilities leads to strength and flexibility, for such a support system makes possible innovation and synergistic problem-solving.

We saw the need for a process for assessing the degree to which department groups were able to move toward these goals of trust, openness, realization and interdependence. Gibb’s Environmental Quality Scale describes ten phases, five of which we found useful in analyzing the cases under study.

The first phase he calls E.Q. I-Punitive. In such an environment, people attempt to “reduce visible or prospective chaos and danger by punishing others.” In academic departments or administrative teams, occasionally one sees this approach used to bring a new professor into line with the expectations of the (senior) faculty, or punishment may be visited on a recalcitrant chair whose behavior is far from the expectations of those who “placed” him or her in this leadership position. Punishment is sustained by guilt and hostility and can be visited on anyone who has seriously disrupted the expectations of others in the group.

In the second phase, E.Q. 2-Autocratic, “power and order and structure are the key themes”. Academic groups who have very real fears of disorder and powerlessness may adopt this approach which is associated with a morality of obedience to authority for the common good. This presumes a value-laden view of responsibility and an assumption that people must accept strong authority as a necessity. The high costs of these phases will be explored later.

The third phase is E.Q. 3-Benevolent. Here there is a nurturing and caring environment in which autocracy is muted, although members of the group still feel a concern for order and structure. In this situation, a group desires a maternalist (or paternalist) approach to leadership in order to provide the group’s affiliation and security needs. People in such groups appreciate the chair (dean or vice-president) who looks out for them and their needs, and the dependency and resistance which result are of little problem to the members. The benevolent leader uses rewards and punishments fairly as a means of control. The processes are not seen as manipulative because they “work.” The negative results are seen in some of the cases we will present.

The fourth phase is E.Q. 4-Advisory. This phase utilizes consultative help, data collection, and enhanced communication at all levels. Leadership (and management) is seen as a rational, scientific process. In this phase, fear and distrust are less evident and there is a movement away from dependency upon the leader as a motivator. The wisdom and decision making competence of the group are realized and practiced.

The fifth phase is called E.Q. 5-Participative. In this phase, with increasing trust, is a focus upon participation. Decisions are made by group consensus and thoughtful group choice. The group is involved in all phases of management or departmental operations and decisions. This approach does not mean that every detail is discussed by the total group; effective delegation is employed. Participatory management, the ideal form of social environment, results from a high degree of trust among the members of the group.

Application

In order to facilitate a group’s evolution to higher phases, diagnosis and clarity about “what is” is critical, along with a re-examination of the values embraced by the sub-unit. Acknowledgement of the group’s present state and the desire to change from that state are two of the prerequisites of movement and growth. Occasionally, a group needs outside intervention, someone to hold up a mirror and say, “Look, this is what you are like and here are the data that confirm the reality of this image.” In the cases we will discuss, outside intervention was employed, with one or both of us serving as the consultants. Early in the process of each intervention, we were involved in feedback of some sort and getting commitment from the group and/or the leaders that change was wanted and needed and that both leaders and groups would be actively involved in the change process.

We needed a helpful framework from which to observe the culture and movement of the department in question. A checklist and guidelines based on Gibb’s TORI theory of organizational change provided such a framework and direction for future inquiry. The checklist raises ten basic questions about the organization:

Where is the movement or energy in this organization or sub-unit?

What systems are functioning ?

What is the mission ?

How is its uniqueness nourished

Is there an open feedback system ?

Is the energy focused on the mission ?

What blocks the energy flow toward the mission ?

What collaborative interfaces need to be created ?

What can be done to foster the sense of community ?

How can simplification enhance the infinite potential of this organization?

Sample Case

Unit: moderate-sized department in a School of Fine Arts in a large public university.

Background: several years of persistent internal conflicts in the department”

Problem presented: serious differences between the dean and the department.

Diagnosed problem: conflict/cooperation.

Focus of attention: department chair faculty.

Mode of intervention: data feedback and process consultation; data feedback and team building.

Problem/Situation/Setting

This department was concerned because it appeared that the dean’s perceptions of the department’s operation and his views regarding its future were very different from the perceptions held by the faculty. One of the stated plans of the dean was to bring in a new chair from another institution. He implied that the changes and improvements needed in the curriculum and program of the department could not be achieved without outside leadership. University administrators had for some months expressed concern over the amount of energy being used/wasted in intra-departmental conflict, while curricular changes and program improvements were receiving little attention.

The Intervention

One of us agreed to assist this department in a self-study aimed at improving the ways the department was making decisions, solving problems, and handling conflicts, both internally and with the school administration. The faculty agreed to be involved in this project, anticipated to continue through at least one academic year. Using a data feedback approach, the facilitator or consultant assisted the department in gathering information in a variety of ways.

Student input: One aspect which was basic to the project was that of checking the degree of fit between students’ needs and departmental offering and services. A questionnaire was used with a variety of programs and classes. Five group interviews were also held with students.

Staff input: The staff of the school was interviewed as a group, and their perceptions were summarized, distributed to, and discussed by faculty.

Administrative input: At the request of the chair and the faculty, five interviews were conducted with administrators for the purpose of exploring the strengths of the department and possible new futures. These data, collected in the fall, were swnmarized and distributed to all faculty of the department. Included in the interviews were the President, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Dean of University Planning, and the Dean and Associate Dean of the School of Fine Arts.

Questions included in the process were:

How do you view the strengths and limitations of the.______Department? How would you rate the quality of the faculty generally? the program?

How do you view the contribution of the department to the University as a whole?

What contacts have you had with the faculty of the department? How do you view their commitment? their communication?

What do you anticipate happening in the University or in the community which could affect the future of the department?

What alternatives do you feel might be pursued?

A summary of the data from these interviews was presented in written form to faculty for discussion.

Faculty input: An extensive questionnaire was developed by a faculty committee and was administered to all faculty of the department.

Feedback Session

A two-hour session was held with the faculty in which the data from the surveys were swnmarized and discussed. The members of the group were next asked to picture the department as it might be functioning twelve mouths later. Faculty wrote out these positive images of how the department could be functioning. Out of these images, faculty developed four or five goals for the department for the coming year.

One spinoff of this feedback session was the decision of the group to have a workshop on handling conflict effectively. Such a workshop was held the following mouth, with a majority of the faculty participating.

The Result

Short-tenn results:

Six months after the self-study process was completed, faculty were asked to respond to a follow-up questionnaire; a majority responded. To the question, “Should this service (help with self-study) be made available to other departments?”, the response was a unani mous “yes.” Faculty gave very little definitive data as to why they thought the effort was successful. Generally, they spoke positively about some shift in attitude toward change. They generally felt that they ‘‘now know the strengths of the department quite well.” Some disappointment was stated over too little progress or change. Although some faculty had high expectations for change and improvement which were not realized, even these persons made comments about progress. A number of the faculty mentioned the value of new data regarding staff perceptions which they had not had earlier. The self study process “cleared the air between the dean and us [the faculty of the department],”said one.

Follow-Up Evaluation

Interviews with the dean and department chair some six years after the intervention reveal a department with relatively little internal conflict. There is also a good relationship between the dean, a new person in this role, and the department chair, the same person who was chair during the self-study. In retrospect, he enumerated several positive benefits of the self-study project:

“The self-study strengthened our unit; it also strengthened our ability to influence the dean.”

It clarified the issues in the department.

The process gave the department intensive data which were useful as they moved into their self-study process for accreditation.

It provided new data as to the image of the department in the minds of staff, administrators, students, and faculty.

The longevity of the chair’s term is a positive benefit. “A very strong benefit of the self-study project was that it allowed us to be able to retain the same chair for ten years.”

The new dean’s responses included the comment that, despite the general problems and difficulties in higher education, this department is relatively free of internal conflicts. The dean also stated that she feels good about her relationship to the chair and to the faculty group.

Analysis

At the time of the initial intervention, it appeared to the consultant that in many ways the department was characteristic of Gibb’s EQ 3 Benevolent Phase. The faculty appeared to have a need for a paternalistic leader, one who would look out for their needs and interests, even if it meant directly opposing the dean.

At the time of the follow-up interviews there were many indications that the group had certainly progressed to EQ4 Advisory Phase, and in most respects had achieved the Participation Phase (EQ5). Participation appears to be a central mode of operation, and most of the earlier distrust is nonexistent. Decisions are made democratically, often by consensus, and the chair, who is currently in his tenth year, uses an effective style of consulting with key faculty regarding important decisions. The department is moving toward a participative management approach which would be impossible without a rather high level of trust among the faculty.

The earlier internal conflicts over power issues are nearly non-existent. The climate of the department has allowed the chair to mature in his leadership style, with increasing effectiveness on the part of the faculty.

Gibb’s Checklist

1. Where is the movement or energy in this organization or sub-unit?

The main focus of energy was on autonomy and self-control. Initially, faculty members did not see themselves and their future health as a department related in any way to the dean. They saw him as a new irritant in the system, one who did not fully understand their purposes and needs. Some even saw him as one who threatened their autonomy through his notion that a new chair should be brought in from the outside. This department now sees the dean as one who understands their purposes and who has given evidence that the department can count on support at the school level. Now they are not as concerned with autonomy; on-going projects and professional presentations to the community seem to take the bulk of their energy. One can only guess whether the intervention had as great an impact as the appointment of a new dean.

2. What systems are functioning?

The chair has developed a system of consulting with key faculty on decisions or items where he needs input. This has not only been successful from the point of view of the department chair but it apparently is also appreciated by the faculty in the department. They report less departmental conflict and fewer “ulcer-producing” departmental meetings.

3. What is the mission?

The mission of the department seems clear: to attempt to provide students with both the knowledge and skills to be effective artist/performers in any one of the five different areas of the department. An unofficial mission six years ago appeared to be to maintain departmental autonomy and prevent serious incursions from the dean’s office.

4. How is its uniqueness nourished?

To some extent the uniqueness of the department is nourished by the chair, who appears to understand the faculty, perhaps because of his history as leader for the last ten years. The current dean has supported the leadership of the chair and the energy of department generally. The new vice-president has a strong interest in the arts and is supportive of the school and department.

5. Is there an open feedback system?

It now appears to be ahnost an on-going assumption of the department that faculty should use in a routine way some form of data gathering to determine the extent to which there is a good fit between departmental offerings and services and the needs of students. The chair’s system of conferring regularly with key faculty also contributes to systematic feedback.

6. Is the energy focused on the mission?

Now the energy of the department seems to be more directly invested in its primary instructional purposes.

7. What blocks the energy flow toward the mission?

In the department’s earlier history, energy was invested in internal conflict. At the start of this intervention, a considerable amount of faculty energy was used up by anxiety about preserving power and prerogatives. There are no obvious blocks at this time.

8. What collaborative interfaces need to be created?

A follow-up interview with the chair will explore this area.

9. What can be done to foster the sense of community?

This department is aware that social activities would promote a greater sense of community. Despite a resolve, few of these have been held in recent years. A heavy schedule of public presentations makes it difficult for the very busy faculty and staff to wedge out time for this important activity.

10. How can simplification enhance the potential of this organization?

Six years ago, during the self-study for departmental renewal, the department decided that it needed a process person selected from the faculty, someone with expertise in group process, who would intervene in faculty meeting to reflect with the faculty on the processes employed. Recently, when the chair was asked if this idea was ever implemented, he said, “No, and we still think it’s a good idea!”

What contributed to the success of this case? The chair and the department were willing to do follow-up work. There was extensive discussion about what was working. The faculty took the study seriously and were willing to contribute data. From interviews with the chair, the consultant was able to monitor progress. The department was receptive to the idea of doing a follow-up workshop, which gave them a chance to once again look at the quality of their problem solving and conflict management processes.

The initial work with the department made faculty members receptive two years later to going into the Higher Education Management Institute (HEMI) data/feedback program, which provided them with similar perceptions from faculty, staff, students, administrators, and alumni.

They also had a two-hour workshop focused on management of conflict principles, which gave them the opportunity to apply the concepts to department issues.

Additional Outcomes

The attitude of the administration concerning the department and the chair has made almost a 180 degree turnabout in the past six years as the department has minimized conflict and found positive ways to communicate their needs and wishes as a department.

Discussion of Other Interventions

Not surprisingly, interventions that we carried out on our home campus tended to have more follow-up and an on-going occasional relationship between the consultant and the client department. These cases had a higher degree of success than those in other places.

On other campuses, a typical mode of operation would be to interview key persons by telephone in order to agree on entry concerns: the nature of the problem and the expectations from the consultative process. A visit to the campus to interview each of the faculty usually preceded a one or one-and-one-half day team building or conflict managing retreat. Often a simple questionnaire instrument was used to gather additional data before the retreat. Individual faculty interviews tended to employ an open interview approach based on three questions:

What are the problems and concerns you have as a member of this department?

What are the assets and advantages of this department?

What do you consider some of the important ideas and possibilities for the near future for this department?

The success of our work with departments on campuses of other colleges and universities seems mixed. In some situations, clients made effective use of the short-term intervention and significant improvements were reported. Other interventions appeared to have little or no lasting impact when clients were asked to reflect two to six years after the intervention. Local insight and initiative were key success factors. The length of the intervention also appears to be related to success: one-day interventions are far less likely to produce impact. Careful in-depth interviewing of all faculty of the department is a highly desirable procedure. Systematic follow-up by the external consultant can also enhance the positive potential of the intervention.

Summary

Our experience as consultants to departments in conflict rein forces our belief in the value of using conflict resolution for improving the academic department as a functioning unit. We hope we have outlined processes and interventions that can begin the healing of fragmented faculties, drawing them back together in a movement toward productive team work. We urge other consultants to share those practices that work and that make it possible to avoid the pain caused by internal divisiveness.

References

- Argyris, Chris, Reasoning, Learning, and Action (San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass, 1982), p. xix.

- Gibb, Jack R. Trust: A New View of Personal and Organizational Development (LosAngeles, California: The Guild of Tutors Press, 1978).

- Schmuck, Richard A. and Matthew B. Miles, Organizational Development in Schools (Palo Alto, California: National Press Books, 1971), p. 8.