Photojournalism and Social Movement as “Theatre”: A Critical Reading of “The Sunflower Movement” Photographs

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

1. Introduction

The Sunflower Movement, in which students and social activists occupied Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan in the spring of 2014, to demand rescinding the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), occupies an important historical place in Taiwan's democratization movement and deserves thoughtful writing, documentation, and commentary. The Sunflower Movement has created an immediate and lasting effect on the political reality.[1] With increasing accessibility to digital photography tools, the participants of the movement had become fully equipped with cell phones and other photographic devices. As a result, after the conclusion of the Sunflower Movement, there were an unprecedentedly large number of publications with text and images about the movement. In the face of such a “festival of images,” this article will discuss representative photographs of the Sunflower Movement and analyze a few characteristics and problems prevalent in mainstream photojournalism and documentary photography.[2]

The practice of photojournalism and documentary photography has a longer history in Western industrial countries, and these experiences have been introduced or copied by Taiwan's media and academic circles so extensively that they have become professional benchmarks and practice models for reference and imitation. In addition, starting with the exhibition Eternity in a Moment: 70 Years of the Pulitzer Prize for Photojournalism, 2013, which received huge crowds of visitors and business opportunities, as well as A New Age of Exploration: National Geographic at 125 in the same year, and the To See Life, To See the World in 2014, private sector commercial exhibition agencies have brought exhibitions of photographs from long-standing American publications or news organizations and documentary photography to the public. Cultural and creative parks, art galleries, and museums throughout Taiwan have collectively promoted the culture of American mainstream photojournalism and documentary photography to the wider public.

Therefore, this paper will trace the origin of the Western academic and critical debates on whether photojournalism and documentary photography could represent “truth,” and to conduct a preliminary content analysis of 70 years of Pulitzer Prize-winning images for Photojournalism in the United States that are the most familiar to professional and general readers in Taiwan, as a starting point and basis for analyzing the photographic works of the Sunflower Movement. [3] This paper then analyzes the differences in the historical context and practical experience between the photographs of political resistance in Taiwan's democratic movement from the late 1970s to the 1980s and the photojournalism/documentary photography in Western industrial countries. Finally, this paper examines four groups of representative works of professional photojournalists from Taiwanese newspapers along with Before the Dawn: The Sunflower Movement (Tian guang: taiyanghua xueyun sheyingji), a photobook collectively edited and published by participants or supporters of the movement through fundraising. The four sets of professional photojournalistic works sampled in this article were taken and chosen by four photographers—Fang Jun-zhe and Chen Zhen-tang from China Times, and Hang Da-peng and Chang Liang-I from Apple Daily—each of whom selected dozens of representative photographs of the movement.[4] As a comparison to the professional photojournalistic works, the photobook Before the Dawn stands out both as the most representative among the publications on the movement and the most suitable for discursive analysis.[5] Before the Dawn raised funds and collected photos for publication through digital platforms. The production team raised nearly $7.5 million and received over 13,000 photos from more than 800 photographers.[6] The initial circulation was 30,000 copies, which surpassed other similar publications.

Through the analysis of these images, this paper proposes the following arguments. First, the concepts and practices of photography in mainstream mass communication in Taiwan, in general, inherited the concept and tradition of Western photojournalism/documentary photography. The main characteristic of the practice represented by the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs over the past 70 years is the emphasis on capturing the sensory effects of events and the dramatic atmosphere of the scene. For the mainstream commercial media, sensual and dramatic news photos not only are the "essence" of photojournalism, but also bear the function of attracting readers to increase the sale of newspapers. Secondly, those who documented Taiwan's dissident political movement in the 1980s with images were not merely spectators or objective recorders but active participants in the democratization movement. Their testimonial news and documentary photographs were meaningful in the early stage of the democratization process in Taiwan. Thirdly, among the photographs of the happenings of the Sunflower Movement, differences could be discerned between the ones made by photojournalists and those by the participants. However, these photographs, regardless of the photographers, mostly depict various dramatic or sensational moments. Moreover, despite the difference in their political stances on the CSSTA, the photojournalists of China Times and Apple Daily adopted similar approaches in their photography. Fourthly, the photobook Before the Dawn is designed as an “image theatre.” It simplifies the onsite experience of this movement, which is heterogenous and multilayered; in the process of photo selection, the book has become an illustrated story of semantic hegemony, with a black-and-white view on politics and morality. This article argues that this reduction resonates with the claims at the main stages and main podiums inside and outside the Legislative Yuan, the homogenized self-presentation of which gradually obscured the high degree of heterogeneity of the participants and the various claims of the protest.

2. Debates on Truth, Photojournalism, and Documentary Photography

Whether photojournalism and documentary photography can represent the truth and how to effectively convey political discourse have been debated in the Western academic and critical circles for nearly a century. These debates started early in the West because the invention of photography and its application to news media began in the Western industrial countries; the fact that these debates have lasted so long demonstrates that both "photography" and "truth" are complex matters or concepts. This section will divide key discussions and debates into three parts and provide a basic overview.

2.1. Discussions on the Relationship between Photographic Truth and Political Discourse

Critical discussions on the relationship of realistic photography, “truth,” and politics were largely initiated by Western theorists of materialism. In the 1930s Walter Benjamin, one of the pioneers of this theoretical lineage, examined the changes of the witnessing function of photography, emphasizing that captions were the primary intermediary in the interpretation of photographs.[7] In his later writings, Benjamin raised sharp questions regarding the objectivity and consumerist nature of photography. He argued that, with “a modish, technically perfect way” , the New Objectivity Photography was able to “turn poverty...into an object of enjoyment."[8] Not only has human suffering been tampered with, argued Benjamin, but photography is also “making human misery an object of consumption.”[9] In their respective works, critics such as John Berger, Jean Mohr, Susan Sontag, and Martha Rosler have analyzed the commodification and exploitation of documentary photography in a capitalist society from a materialist point of view, arguing that humanistic or concerned documentary photography could provide neither revelation nor critique of politics.[10]

However, the richest and most eloquent critique of photography as a way of examining society, representing reality, understanding the world, or intervening in politics comes from the writings of Western post-structuralist and Foucauldian photographic theorists. Michel Foucault proposed that the doctor-patient relationship is a one-way gaze from the observer (doctor) to the observed (patient): in this process of acquiring cognitive/diagnostic knowledge through viewing/observation, the order of “truth” of medical knowledge was established.[11] Foucault furthered this exploration through the panopticon as a metaphor of how surveillance and discipline were normalized in modern society.[12] Based on these original studies, Foucault developed a theory of power and knowledge.[13] To apply it to the theory of photography, realist photography is constructed as the effective means of knowing truth, and every society has a complex mechanism for the production of truth, which Foucault calls the “regime of truth.”[14] This power is maintained through intricate operations, the key to which is the discursive construction of knowledge through “seeing.” Foucault's critical theory of discourse analysis has become a powerful way to analyze the relationship between photography, truth, and politics.[15]

Inspired by Foucault's theories, some post-Foucauldian structuralist critics have re-evaluated realist photography. John Tagg paid great attention to the connection between Western documentary photography and social political context, examining how, in this relationship, photographs were used to support surveillance, the normalization of the control of political decision-making, and the legitimization of ideologies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[16] He also analyzed the “social production of truth,” examining the production of discourses of “suffering” and “social problems” in the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs promoted by President Roosevelt’s “New Deal” administration in the 1930s, and questioning the role of photography in the representation of “suffering” in a middle-class-oriented country and the resulting power of the photographic discourse.[17] Twenty-one years after the publication of the above-mentioned work, Tagg continued to examine 19th century Western photography as historical archive, the realism of 1930s American documentary photography and Walker Evans’ resistance to meaning, and what he calls “the violence of meaning” in photographic rhetoric.[18] Another major Foucauldian theoretical figure is Allan Sekula, whose work has focused on the construction of the meaning of photography and its political role.[19] He elaborated on the issue of the universal language of photography and examines the rationalization and normalization of existing power relations in the photographic archive by means of materialist analysis and theories on power and knowledge.[20]

2.2. Debates and Critiques on the Tradition of Western Documentary Photography

Thanks to the maturity of economic and material conditions in Western countries, especially Great Britain and the United States, the practice of documentary photography has developed considerably since the 1930s. Derrick Price notes that in major Western countries, large-format illustrated magazines were already widely available, and these publications enabled photography to be commissioned and published.[21] They included Weekly Illustrated and Picture Post in Britain, Life and Look in the United States, Vu and Paris Match in France, and Stern in Germany. The introduction of these print media led to great changes in photojournalism and social documentary photography.

The specific socio-historical context and political background of the 1930s onward also contributed to the establishment of a documentary tradition. Britain was facing the rise of Fascism and the Second World War, as well as social confrontation and domestic class conflict, especially between the North and South.[22] The collective sentiment of patriotism was desperately needed to fight against the common enemy, and British society sought new ways to generate "social transparency" in order to reduce class conflict and to build social stability.[23] In this historical context, British social documentary photography of the time, particularly those in Picture Post and Mass Observation, offered the “eyes of society” that can see reality openly, unobstructed, and “objectively.”[24] Stuart Hall sees the magazine’s emphasis on the commonality and representation of ordinary people as an effective social rhetoric, a democratization of the photographic subject, and examines how it eventually became a front for reformist photography.[25] Terry Morden, on the other hand, focuses on the magazine’s efforts to help build British consensus politics and national memory.[26] John Taylor points out a characteristic of Mass Observation: it is full of ‘objective’ photographs of the working class, predominantly by middle-class observers.[27]

Meanwhile the United States was in the Great Depression. The government used documentary photography to promote its agricultural revival policy of the New Deal.[28] The FSA’s documentary photography was arguably the most influential documentary project of the 1930s in the United States. In Tagg’s words, it effectively launched the photography project in a way that produced and conveyed “truth” to the public in a powerful way. The rich photographic legacy of FSA photography itself has been subject to much scrutiny by critics of photography, including debates over the work of individual photographers, which challenges the collective and calculated work of ideological and social control that FSA photography engaged in. For example, how the “humane and caring sentiments” in these photographs and documentary photography created an “ameliorative effect”[29]; how FSA turned structural problems into individual issues, and made photography a “documentary enterprise”[30]; and how documentary photography eventually served as “a deep-seated apparatus of surveillance, transformation and control.”[31] Peter Szto argued that, in the history of social welfare development in the United States from 1897 to 1943, documentary photography was a very effective tool for persuading and promoting social welfare policies, which also helped publicize the results of the government's social welfare work.[32] This is similar to the confirmation of the Roosevelt administration’s agricultural policies offered by the FSA photography.

As a result, the Western documentary tradition has been in full bloom since the 1930s. The social, political, and cultural impacts of documentary photography were far-reaching, and in the decades that followed, the “discursive validity” of realist and humanist photography was demonstrated in succession, for instance the works by Eugene Smith and Don McCullin, or the famous The Family of Man exhibition launched by MOMA in 1955. Sekula criticizes this exhibition as an attempt to “universalize photographic discourse.”[33] However, even in the 1990s, and now in the early the 21st century, the humanist and reformist practices in realist photography are still well received, and the “currency” value of Western documentary photography remained as strong as ever.

The work of Sebastião Salgado is the most representative contemporary example. His two world-famous documentary works, Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age (1993) and Migrations: Humanity in Transition (2000), are the pinnacle of this "Family of Man" style of grand visual narrative and unified photographic discourse in the West.[34] The aestheticized photographic language in these works presents a universalized meaning that obscures and erases the highly differentiated local contexts and causes behind each subject; at the same time, these works ignore the real culprits of suffering and injustice, namely the complex but "invisible" (i.e., not to be "witnessed") international political structure.

Recent studies on documentary photography continue to reflect on the sentimental and aestheticizing narrative style of traditional documentary photography and attempt to propose ways to break free from this documentary malaise while making photography politically meaningful. Jorge Ribalta, a Spanish curator active in contemporary art, in his exhibition companion book Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism (curated for the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid), argues that documentary photography must recreate a self-critique and a “neo-avant-garde” articulation to overcome modernist myths on photography such as its transparency and universal meaning.[35] Agustin Berti and Andrea Torrano analyze “flawed devices and other heterodox ways” the Argentine photographer Seba Kurtis adopted to represent migration, arguing that it is Kurtis' mix of ethics, politics, aesthetics, techniques, and themes that re-invigorates photography to fight against the epicizing, sentimental, or aestheticizing images of traditional documentary photography, as well as the depoliticizing effect brought by this approach.[36] In her study on the aesthetics and politics of “aftermath photography,” Veronica Tello takes Australian photographer Rosemary Laing's work Welcome to Australia as an example to emphasize that, if the photographic subject matter in the aftermath of a disaster or trauma does not create photographs directly confronting the brutality of the incident or experience itself, then "aftermath photography" will easily fall into an unrealistic, detached, and exoticizing theatrical effect.[37]

2.3. Debates on Photojournalism in the West

Photojournalism and documentary photography are essentially in the same category in terms of how they obtain visual content to represent the world. They both believe that the essence and unique language of photography lies in witnessing and capturing images onsite without tampering with them. Frank Webster points out that a particular social and cultural context, perspective, and temporal structure of seeing the world has ungirded the concept of photojournalism. Newspaper organizations may not be directly responsible for this way of seeing, but they are powerful and effective in constantly consolidating this established mode of viewing and its particularities, disseminating them day after day through the publication of photographs.[38] He also pointed out that the medium of news photography is usually a conservative culture, as it is committed to maintain the current economic and social status quo. With the mainstream position of the general news media in society, it is in the interest of such media to support the mainstream social consensus and minimize the need for change. To achieve this, an effective way is to support and maintain an established way of viewing politics and society through new photography. Since mass media is “not only a business, but a big business,” photojournalism has two roles and functions here: it provides a way to maintain the status quo, and it is also a consumerist visual commodity.[39]

In his study of British press photographs from several major conflicts (World War I, World War II, the Falklands War, and the British battle against the Irish Republican Army IRA), John Taylor discovered that when it came to “national security,” especially IRA terrorism, the media, which normally appeared to be monitoring the state, automatically took the same perspective as the state, i.e., presenting photographic messages from the official point of view.[40] Taylor further examined several psychological effects provided by news photos of war and disaster scenes. These effects came from the shocking, unbearably graphic images and the temporary “pain relief” they brought.[41] Many of the humanist photographs from war or disaster sites, such as those by James Nachtwey, a renowned New York war photographer, only continue to churn out a sense of pity from the reader, but fail to generate the motivation for the viewer to further understand the disaster, because such pity will soon create a “compassion fatigue” effect.[42]

The question of whether news photojournalism is a faithful record of events, whether it can provide or maintain readers' trust in the “truth value" of news photographs, and whether it can provide valuable knowledge or understanding that can inspire readers to take politically meaningful action has remained a focal point of debate in Western photographic studies. In On Photography, Sontag expresses an unreserved negative and critical stance on this issue, arguing that “Despite the illusion of giving understanding, what seeing through photographs really invites is an acquisitive relation to the world that nourishes aesthetic awareness and promotes emotional detachment.”[43] Sontag's eloquent arguments about photography and reality are, after more than twenty years, doubted by herself in Regarding the Pain of Others. While Sontag's analysis of some of the latest practices in documentary photography remains sharp, she revises and reverses herself significantly on whether war photojournalism can generate political meaning and possibilities for action. Having experienced firsthand the war in the Balkans in the early 1990s, and life in the war zone in the city of Sarajevo, she believes that photojournalism depicting war is still needed, and that it is still useful for Westerners to be aware of the existence of war and suffering.[44]

Whether photojournalism can still fulfill the “contract” of “reproducing the truth” and the long connection or tension between the two is a central concern of many critics and researchers about photography. Some studies have pointed out that the advent of the digital age and its application to capturing and editing news photographs has caused great anxiety among many professionals who adhere to the traditional ethics of photojournalism and who are eager to defend the photographic ethics that images must be faithful to the truth and cannot be tampered with.[45] Taylor examines the link between photography and reality in relation to the large number of photographs of U.S. military abuse of Iraqi prisoners that have been published in Western newspapers in recent years. He found that the "contract" between the two is tenuous because many of the photos of prisoner abuse have been digitally manipulated. While some of the tampering must be rejected, others are largely acceptable as long as it is unnoticed, or because they meet the established expectations of what is real in photography.[46]

With regard to the reaffirmation of mainstream values in photojournalism and its relationship to the nation, Mendelson points out the continual affirmation of the American myth by comparing the work of Norman Rockwell, an illustrator who provided the cover images for the Saturday Evening Post, and feature photography in contemporary news.[47] Liam Kennedy, in a study on mainstream American news photographs and digital photographs from alternative media in documenting the Iraq War, argues that photojournalism, while supporting the geopolitical stance of the nation, also has the potential to challenge that stance, but the latter is almost always found in alternative or niche media.[48] Åker, in a study comparing the front page photographs of several Swedish “quality newspapers” eight years ago and from the present, found that the preference for large, visually pleasing, and sometimes enigmatic photographs on the front page of newspapers has not changed much in the past eight years. Åker further points out that this “journalism-as-art” means a move away from the traditional concept of objective photojournalism. He believes that there is still hope for the future of professional photojournalism if the public gradually understands that photographs are a medium for interpreting and constructing reality, rather than a part of it.[49]

Some other theorists have alternative views on the “contract” between photography and the real world. John Roberts is not convinced by the critique of realist photography in Western photographic theory, which he refutes by arguing that it is misleading for critics to confuse the critique of Western positivism with realism.[50] Judith Butler, a scholar of gender, has also focused her research on the writing of photography in recent years. Her psychoanalytic study of U.S. military photographs of prisoner abuse in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraqi suggests that photographs of the absurd and brutal acts of abuse do not merely have a numbing effect but allow first-world readers to examine why Westerners can turn a blind eye to these cruel and inhumane acts, and therefore the photographs still have political significance.[51]

Ariella Azoulay also re-evaluates the connection between photography and reality, and its role in politics. She argues that photographs can be used to create a kind of "photographic citizenship" for people who lack power (such as Palestinians without citizenship in Israel, or women in Western societies), to whom photography became a kind of right of the citizen.[52] Bangladeshi photojournalist Ismail Ferdous, citing his own photography of the 2013 disaster in Dhaka, where the collapse of a garment factory building led to the death and injury of more than 3,000 people, argues that photojournalism has the spirit of activism, allowing the viewer to reflect on core beliefs and foster a sense of mutual responsibility, which could turn the viewer into a kind of international citizen. He believes that photojournalism has the power to make people either turn their heads away or ask questions, the latter of which is the purpose of his photography.[53]

Susie Linfield, following John Roberts, is one of the most vocal defenders of the value of photojournalism. Like Roberts, Linfield begins her book by examining and refuting critical photo theorists/critics, from Benjamin, Barthes, and Berger to Sontag.[54] Discussing Robert Capa's photographs, she reminds us that we do not need to choose between a naive and gullible belief in the appearance of reality and an annalistic suspicion of the world, but rather to identify what each form of testimony and documentation could offer to our understanding of the world. This is a valid argument, but it does not answer the question of what to do if the photographic method of witnessing is not effective in understanding the world.[55] In discussing the famous war photographer James Nachtwey, Linfield criticizes the photographer for always focusing on his own interest in abstract forms and aesthetic expressions, regardless of whether he is photographing subjects “post-9/11” or the Islamic world, which offers little more than dramatic and startling images. On the other hand, Linfield states that Nachtwey's photographs can encourage closer observations and therefore still have their value.[56] Such ambiguous and contradictory arguments fill the entire book, which seems to show that the defenders of traditional photojournalism certainly have the passion for benefiting mankind and the insistence on spreading justice, but their thinking about photography, truth, and politics remains inadequate

3. The Promoter of “Image Theatre”: Pulitzer Prize for Photography

While idealistic critics of traditional photojournalism and documentary photography are determined to defend the value and political role of this tradition, some seasoned veterans who practiced photojournalism are more honest or pragmatic about this profession. In Witness: The World's Greatest News Photographers of Photojournalism (2012), Reuel Golden, an author highly experienced in the profession, while recognizing the value of photojournalism, nonetheless points out its characteristics and problems: “Since the photographic medium entered the field of news reporting, photojournalists have almost aimed at subjects of human struggles for survival. War, civil unrest, famine, natural disasters, poverty, homelessness, etc. have been the materials of tragic stories told by news photographers over the past 150 years.”[57]

Golden states frankly that photojournalists work in a highly commercialized environment where there is a constant demand for photos and stories of negative subjects, as “good news is never good for newspaper sales.”[58] In this reality, he sees the aesthetic of photojournalism as “making the images as impactful as possible, which usually means that some of the scenes of misery and suffering must be glorified.”[59] Golden points out that photojournalists are highly aware that “a photo with precise composition, stunning graduation, and perfect lighting” is likely to get the reader's attention and after a “dramatic” news event is represented, the dramatic photographic images of the event tend to remain in people’s memory.[60] At the end of his introduction, he sums up press photography bluntly: “What other important functions can photojournalism serve in the near future? If the 21st century is as full of blood and violence as previous centuries, then photojournalism will continue to play the role of observer and eyewitness. This is bad news as much as good news.”[61]

In “What is a Magnum photograph?,” a foreword to Magnum Magnum written by Gerry Badger, the author of The Genius of Photography, Badger argues that typical Magnum subjects such as war, political strife, and disaster have unfortunately remained mainstream, and Leica cameras and black and white negatives (or digital cameras set in black and white mode) are still the standard in Magnum.[62] As the book itself includes a lot of colour photographs by Magnum photographers, why are black and white negatives or digital images in black and white still the “standard” in Magnum? This article argues that, in an era when colour photography has been widely used, photojournalists still prefer black-and-white photographs as a narrative and aesthetic choice because, after removing the realistic component of “colour,” black-and-white photography can more effectively abstract reality into a visual order with a heightened sense of drama. The drama or theatricality of an event comes not only from the moment frozen by the camera shutter or the temporality it produces, but also from the abstracted and symbolized lines, light and shadows, and emotions. In short, black-and-white photographs with the element of colour removed are more capable of achieving such visual and psychological effects.

With respect to the Pulitzer Prize for Photography, which has the most global recognition and influence,[63] the ways in which the organizers and the public view and describe the Prize clearly demonstrate the nature of this professional photojournalism competition. The public relations literature on the official website of Mediasphere (Shiyi duomeiti), one of the organizers of the first exhibition of Pulitzer Prize shown in Taiwan, dubs this Prize "the Oscar of photojournalism.”[64] I consider this to be accurate. Wang Rong-wen, the chairman of another local sponsor, Taiwan Creative Industry Development Corporation, described in a special publication for the exhibition that he and his team based their management of the 1914 Huashan Cultural and Creative Park, where the exhibition was held, on the concept of “managing space, managing time, managing creativity, managing stories, and managing emotions.”[65] Wang believes that the classic works of the Pulitzer Prize are the exemplary expression of these five types of management.[66]

The biography of the exhibition’s curator, Cyma Rubin, included in the special publication for the exhibition, accurately demonstrates what this prestigious international exhibition of professional photojournalism means and how it should be positioned. Ms. Rubin is the president of Business of Entertainment, Inc. in New York, a producer, director and screenwriter, who has produced Tony Award-winning Broadway musicals, several Warner Brothers and CBS films, and Pepsi-Cola multimedia shows, among others. While the Oscar is generally a competition that recognizes the market performance of mainstream commercial entertainment films in the United States, Rubin, faithful to this business model, sees Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs as a highly dramatic and entertaining commodity with high commercial value. She not only produced and directed the TV special “Moment of Impact: The Story of Pulitzer Prize-winning Photographs” in 1999 for the Turner Network, but also actively served as the curator of the touring exhibition “Capture the Moment: The Pulitzer Prize Photographs” for huge commercial profit. It is therefore fitting, indeed, to call the Pulitzer Prize the "Oscar of Press Photography."[67]

James C. Duff, the CEO of NEWSEUM, the other U.S. organizer of the exhibition and owner of the rights to the exhibition and publication, concludes the preface to the publication with a quote from photojournalist John White: “It is as if we were sitting in the front row of history and we kept saying, ‘Yes, I remember that.’ The Pulitzer Prize-winning works are mirrors of eternal value."[68] We could put aside for now how these “mirrors of history” illuminate people's understanding of history or political and social reality. But the trope of “the front row,” as well as Wang Rong-wen’s claim that the Pulitzer Prize manages time and space, creativity, stories, and emotions, both offer a rather revealing description of the nature and function of this prize.

Sitting in the front row in this “theatre of history,” the audience would see the following historical contents from the 164 Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs over the past 70 years in this exhibition: 1) 68 photographs of accidents, disasters/ famines, and war scenes; 2) 25 eyewitness photographs of conflicts and assassinations; 3) 23 photographs of heartwarming and emotional moments or positive images of political figures; 4) 10 photographs of highlights of humanity in moments of aid and rescues; 5) and 8 photographs of American nationalism and patriotic sentiments. In addition, 16 photographs that touch on social issues, workers, farmers, and other underrepresented classes; 7 photographs of portraits of celebrities; 6 photographs on black civil rights movement or racial conflict, and 1 photograph depicting daily life. One hundred and sixteen photographs—more than two-thirds of the award-winning works from the past 70 years—are on the theme of accidents, disasters, war, conflict, assassinations, and tender, emotional moments.

Figure 1: Milton Brooks, Ford Strikers Riot, 1941. Winner of the 1942 Pulitzer Prize for Photography.

Figure 1: Milton Brooks, Ford Strikers Riot, 1941. Winner of the 1942 Pulitzer Prize for Photography. Most of these photographs, full of drama and narrative tension, stimulate the viewer visually and psychologically, triggering emotional responses just like the plots of Hollywood movies, which make people hold their breath, become startled or surprised, or in tears. The very first award-winning work in 1942, the photograph of eight workers beating a strike-breaker on the strike line of the Detroit Auto Workers Union, already set the format for the photojournalism promoted by the Pulitzer Prize for Photography: a medium- or closeup shot (often with a wide-angle lens) and camera position to capture a moment of action on the scene with a sense of immediacy and dramatic tension. (Figure 1) Browsing through the award-winning photographs of the past years, most of them are of this format, while non-dramatic long-distance shots without much action are rare. Whether sitting in the front row or the back row to history, the audience sees from the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs a visual theatre that captures different subject matters but in a similar nature, and subsequently a highly reductionist understanding of specific events. The photographs stimulate, shock, and touch the sensory nerves and curious eyes of the viewer, but as Frank Webster states, they provide a way of seeing that maintains the status quo, and are themselves a consumerist visual commodity.[69] There are many significant, positive events happening in the world, but as pointed out by Golden, good news does not help newspaper sales. On the other hand, there are too many topics in history and reality that are far more important than accidents or conflicts, for instance structural disasters and hazards, but these issues do not have a scene to be “witnessed.” Eyewitness photojournalism, in the end, can hardly go beyond being a kind of "theatre."

4. A Review of Photography of Political Resistance in Taiwan in the 1980s

The practice of American or Western photojournalism/documentary photography is very different both in context and historical development from the experience of Taiwan's realist photography in social movements and political reforms. Western industrialized countries, which matured in the 1920s-1930s and flourished in the 1950s, had a golden age of photojournalism/documentary photography until the 1980s. Before the heyday of the medium of photojournalism, the Western countries generally had a democratic system and freedom of speech in place. In contrast, the photographic practice of exposing reality or political resistance was still a new and unfamiliar experience in Taiwan after the 1970s, as well as in other emerging Asian democracies, just like the experience of democratization itself. During the 30-year-long period of martial law in Taiwan before the 1980s, there was no photography of political resistance in the strict sense. Even the conscious pursuit for realistic photography was a rare practice, of which Wang Xin, Lin Bai-Liang, Ruan Yi-Chung, and Liang Cheng-Chu were some of the better-known pioneers.

In the late 1970s, there were group portraits of democratic activists at various events or photographs of them on the podium, which were later collected in The Will to Resist: A Photographic History of the Democracy Movement in Formosa 1977-1979 (2014).[70] At the time, the images of political resistance did not go beyond photographs of this kind. One of the most common photographic practices during the Martial Law period was salon photography that shunned from reality. News photography, which had to address reality, consisted of formulaic press photos from the official political propaganda mouthpiece of the party-state, which singlehandedly controlled production and reception. This is testified by the numerous photographs from the Central News Agency and other sources—including those in Taiwan: 50 Years After the War (1995), a source book on photojournalism with great archival value published by the formerly staunchly anti-communist China Times—which highlighted the positive aspects of the Taiwan government and reinforced anti-communist patriotic ideology.[71]

The 1980s, Taiwan witnessed a great release of civil forces and the rise of political resistance movements, which eventually led to the acceleration of the democratization process and the abandonment of martial law. The role testimonial realist photography played in helping to promote political opposition movements, social reforms and democratization in that frenzied era, and the extent to which photography accelerated these political reform timelines, require more in-depth discussion. It may also be hard to accurately assess the political effects of photography at the time. Even if a quantitative study such as those based on surveys is conducted on a sample of people who experienced that era, it could be difficult for people to accurately recall or distinguish how much the photographs of social movements and street conflicts from 30 years ago influenced their political awareness at that time.

In addition to the blurring of memory, the method of assessment could also be tricky. In that era of rising political struggles, there was more than one factor or catalyst that awakened and inspired people to take up actions of resistance. It is difficult to identify a single media form, a specific text, or even the event itself, which was responsible for initiating and guiding individual or collective political struggle and action. Beyond photography, written texts, social events, heart wrenching public demonstrations of grievance by families of political victims in street rallies, small theatre movements, and home videos all interact with each other to influence people's political awareness and will for resistance. Nevertheless, it is worth discussing the possible effects of still images in the political resistance movement in Taiwan, especially in the late 1980s. Looking at the documentary photographs of the era, as well as the corresponding written texts, this paper posits that these photographs demand rethinking and reevaluation. Simply put, although the political purposes and discursive meanings of the photographs of political resistance during Taiwan’s enlightenment period of democratization tend to be singular, often even reductive to people's understanding of the complex political reality—as such understanding could only be valid through careful exploration of history—these photographs still played a pivotal role at the historical juncture of 1980s Taiwan, when for the first time, photographs had the opportunity to reveal the long obscured reality.

It is fair to say that 1980s Taiwan began with the “Formosa Incident” at the end of 1979. In terms of political opposition, the mass arrests of pro-democracy activists in the streets of Kaohsiung immediately stimulated the rise of the Tangwai Movement, which led to the establishment of the Democratic Progressive Party in 1986 and the end of the martial law the following year. During this period, the Tang-Wai Magazine, a peculiar product of the times that was constantly banned and re-registered for publication, contained photography along with text. Although the adoption of photographs by the Tang-Wai Magazine was hardly active or compelling in the first few years of the 1980s, later there appeared publications more adept at using photographs of street movements. For example, the Freedom Era Weekly (Chuangxin shidai) by Cheng Nan-jung published a special issue to report the “520 peasant movement” in Taipei in 1988 with a considerable number of photographs.[72] (Figure 2)

Figure 2: University students at a sit-in in support of the “520 Peasant Movement,” whose heads were trampled by anti-riot police evicting them in the middle of the night. 1988. Photograph by Huang Zi-ming.

Figure 2: University students at a sit-in in support of the “520 Peasant Movement,” whose heads were trampled by anti-riot police evicting them in the middle of the night. 1988. Photograph by Huang Zi-ming. Prior to the lifting of martial law in 1987, newspapers were officially regulated by the government. The Taoyuan Airport Incident on December 2, 1986 was one of the major bloody clashes between the police and the public before martial law was lifted. (Figure 3) Supporters who went to welcome opposition leader Hsu Hsin-liang, who had been banned from Taiwan but nonetheless returned, had a serious confrontation with the military and police. Many of them were beaten, showing bloody faces, by the riot police or dragged inside the riot car for physical abuse. The next day, while other newspapers remained silent about the incident, or only reported one-sided records of injuries to military and police officers, the then Independent Evening Post (Zili wanbao) devoted a full two-page spread to an exclusive illustrated report of the military and police violence. That day’s report was a turning point for Taiwan's newspaper industry, democracy movement, and photography practice: it had a crucial impact on the ensuing election, pushed the Independent Evening Post to the height of popular fame, and broke the long-standing taboo that witnessing photographs of a political nature could not be published in newspapers.

Figure 3: On December 2nd, 1986, the return of Hsu Hsin-liang to Taiwan triggered the Taoyuan Airport Incident, where the public who went to support and welcome Hsu had a bloody conflict with the military and police. Photograph by Song Long-quan.

Figure 3: On December 2nd, 1986, the return of Hsu Hsin-liang to Taiwan triggered the Taoyuan Airport Incident, where the public who went to support and welcome Hsu had a bloody conflict with the military and police. Photograph by Song Long-quan. With the photojournalists of the Independent Evening Post as the main force, joined by photojournalists of other newspapers and magazines at that time, an exciting and inspiring collective practice happened from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, which became a special moment in the history of Taiwan's photojournalism. Wu Yao-kun, Hsu Bo-hsin, Zeng Wen-bang, Pan Xiao-hsia, Liu Zhen-xiang, and Hsieh San-tai of the Independent Evening Post, Chen Guo-ching and Yang Yong-chi of the Independent Morning Post (Zili wanbao), Hsu Bin and Tsai Ming-de of The Capital Morning Post (Shoudu zaobao), Lin Shao-yan, Hsu Chuan-hsu, Huang Tzu-ming, Ye Ching-fang, and Tsai Wen-xiang of the China Times press, Yu Yue-shu and Song Long-quan who published their photos in political commentary magazines, Chen Kong-gu of New News (Xinxinwen), and Chen Bing-hsun of CommonWealth Magazine (Tianxia) were some of the representative photojournalists of that era.

Some of their documentation of the era of political resistance movements have been compiled in several collections, among which the better-known ones include Yang Yongzhi's Congressional Ecology (1987), Song Longquan's Witnesses: Taiwanese People’s Power, 1986‧519 ~ 1989‧519 (1992)[73], and an anthology of the representative works by the aforementioned photojournalists entitled Give Taiwan a Chance (1995), edited by Liu Zhenxiang and published by the Central Committee of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).[74]

At the time, most of the photojournalists who were at the Legislative Yuan or on the streets to capture photographs of political struggle were not the calm, objective recorders like professional photojournalists in the West. Instead, they were supporters or participants, of varying degrees, of the political opposition or various social movements. They were witnesses to the frenzied times, but they simultaneously became part of the collective outburst of emotions, hoping to help the political opposition movement through their cameras and to end the KMT's prolonged stay in power. At the scene of conflict and protest, the personal safety of photojournalists was at risk to a certain extent. They were often inevitably hit by police batons and water cannons. Their bodies and equipment were often injured by fists and sticks amid the conflicts between police and civilians. They sometimes were even mistaken for pro-official media reporters and chased by protesters.

Given that photojournalists worked under these circumstances of bodily experience, working conditions and political stance, the visual testimonies provided by journalistic and documentary photography of the late 1980s embodies a specific discursive quality in the context of that era. In brief, these images enabled the public who were concerned with political reality to see the cold nature of state violence through the visualization of the physical experience of suppressed protesters. At the same time, the photographers’ strong desire to reveal the reality has led to a simplified dichotomy in the narrative and judgment of political morality: the KMT was evil, while its opponents were righteous, virtuous, and victimized. Their message of the democratic movement essentially equated the overthrow of the KMT regime with the success of Taiwan's civil society. Although witnessing photography in general has difficulty offering insights to the complexity of political matters, this simplified and dichotomous mode of understanding has dearly cost the democratization movement in Taiwan to this day. However, even if the learning processes cannot be accelerated and the democratization process has no shortcuts, the photographs of the political struggles witnessed at the scene still had their role at that time, as well as their value as historical archive today. The mainstream media back then did not have full freedom of speech, so witnessing photography, when viewed dialectically, may still be a necessary means or process for political enlightenment for the public at the time. At the same time, the above-mentioned breakthrough of the Independent Evening Post in its report of the Taoyuan Airport Incident also contributed to push the envelope of freedom of expression.

Eyewitness photographs could inspire the underrepresented, the oppressed, or the exploited, serving as a catalyst for mutual inspiration and self-empowerment, but they could also form political myths. In The Wings of Freedom, a memorial publication about Cheng Nan-jung, Cheng’s refusal to be arrested by the authority, photographs of his self-immolation in the magazine's office in April 1989 and the unprecedented funeral procession in May, and his manuscripts, relics, and quotations offer a clear example.[75] Although Cheng demanded the establishment of Taiwan independence, whether his demand was supported or not, his unreluctant martyrdom provided a moral example or a mirror for reflection to the participants of the democratic movement who were not only fighting against the KMT but also dissatisfied with the pragmatism of the Democratic Progressive Party at that time. The funeral photo with a huge profile of Cheng Nan Yung, who had a "New Nation Movement" banner tied to his head, is a piercing visual blade, prompting people to examine their own moral conscience. (Figure 4) However, 25 years later, at the protest sit-in of the Sunflower Movement, Cheng became a "spiritual totem" of the anti-CSSTA cause, which is an interesting phenomenon worthy of analysis. [76] In the next section of this paper, we will return to this scene.

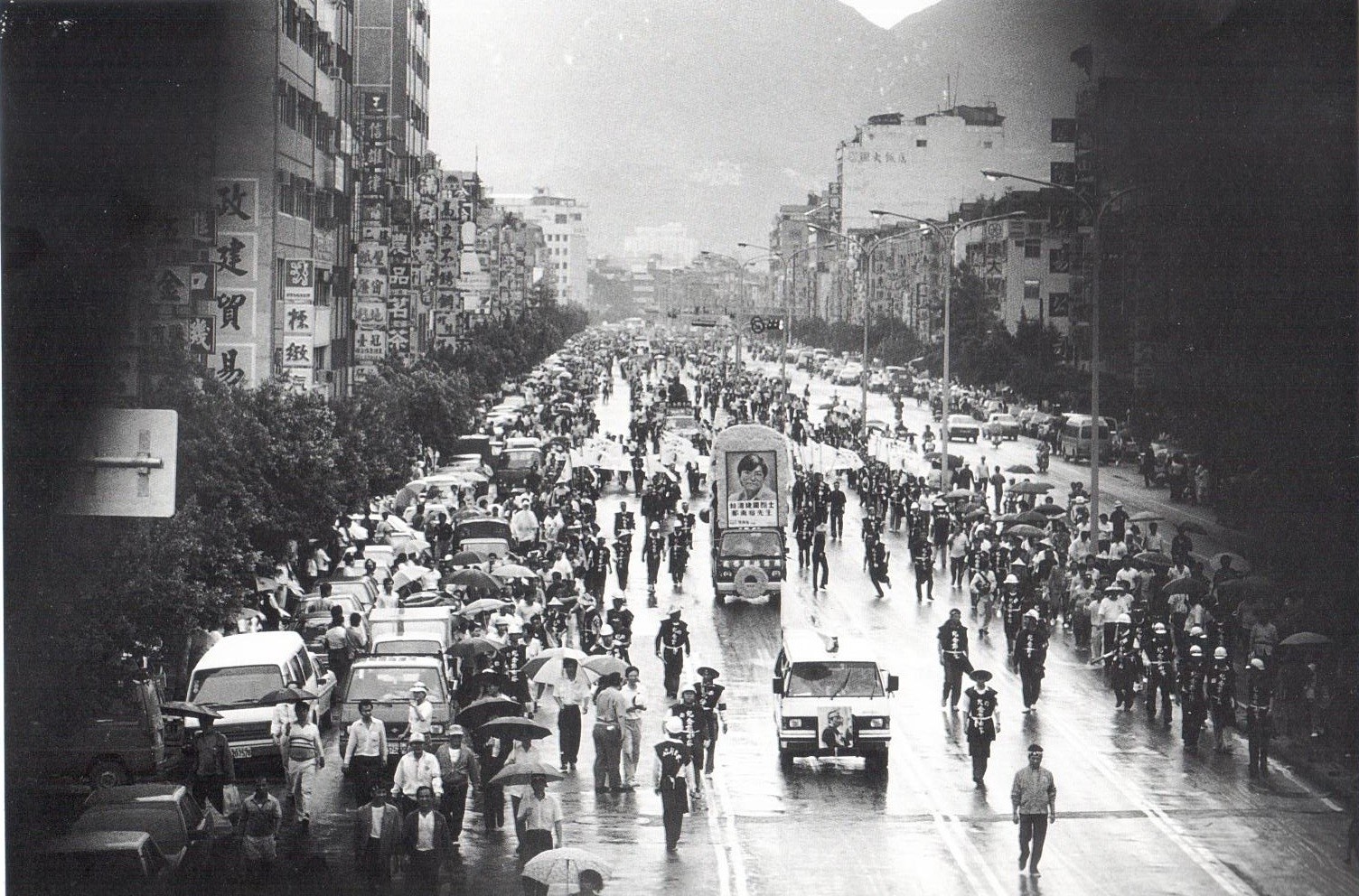

Figure 4: April, 1988, Cheng Nan-jung’s funeral procession. Photograph by Pan Xiao-xia.

Figure 4: April, 1988, Cheng Nan-jung’s funeral procession. Photograph by Pan Xiao-xia.Witnessing photography of political resistance in the late 1980s had its historical context. For the twenty-five years since 1990, social movements, large and small, have continued to use photographs as a witnessing tool and medium of communication. What can the witnessing photographs and their collective role in politics continue to offer in terms of understanding and action? This paper attempts to answer this question by analyzing the photographs of the Sunflower Movement.

5. Reading News and Documentary Photography of the Sunflower Movement

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the Sunflower Movement is unique in Taiwan's past experience of democratization and worthy of in-depth study both in terms of its scale, methods, and influence, and in terms of the photos, graffiti, illustrations, posters, and other visual images produced by the movement. As for the movement itself, to effectively prevent the CSSTA from being negotiated without transparency, young students took the lead in storming and occupying the Legislative Yuan. At the same time, they staged a sit-in protest in the streets surrounding the Legislative Yuan building, paralyzing its proceedings and the traffic around it. At one point, they briefly occupied the Executive Yuan. During the occupation of the Legislative Yuan, they claimed to have gathered half a million people in a sit-in protest in the space around Ketagalan Boulevard. Regardless of the controversies surrounding the demands and methods of the Sunflower Youth Movement, their actions generated broader political concerns of young students and the public, which received great recognition and support from the community.

The photographs and various visual creations produced collectively by the documenters, participants, and observers of the movement include the aforementioned collections of photos by Chihiro Minato and Sarira Huang, and the photographic records of the graffiti posters at the sit-in outside the Legislative Yuan documented by Huang Konglong.[77] In addition, critic Chang Shih-lun also mentioned in his article the paintings and video art by Chen Ching-Yuan and Yuan Guang Ming, as well as analyzing the unique perspective in the report photography by Lam Yik Fei.[78] These works of different forms and perspectives have enriched the diversity of the visual representation of the movement. But as mentioned earlier in this paper, the most representative photographic records are not those images with unique perspectives or viewpoints, but the news photos of press photojournalists and the photobook Before the Dawn, which was published through fundraising and crowdsourcing of photos.

While most of the photojournalists in Taiwan's democratization movement in the 1980s were participants to varying degrees in the dissident political movements, by 2014, photojournalists had generally become professionals calmly documenting the events. At the same time, the participants of the Sunflower Movement were recorders of the political opposition movement because everyone had a camera in hand. What they made are documents of their own experiences of participation. Both the professional press photographers and the participants in the movement basically conform to the concept of testimonial/witnessing photography. Do these testimonial images still have the effect of “enlightening” us about reality or truth today? What is their significance? In this section, I will analyze two types of photographs from the two types of photographers.

5.1. Images Made by Professional Newspaper Photojournalists

As mentioned earlier, the four sets of professional photographs sampled in this article were selected by four photojournalists: Fang Jun-zhe and Chen Zhen-tang from China Times and Hang Da-peng and Chang Liang-I from Apple Daily. The first three photographers’ works are in colour, while Chang Liang-I’s are in black and white. Fang's 50 photos, Hang's 88 photos, and Chang's 48 black-and-white photos basically cover the occupation and sit-in inside and outside the Legislative Yuan. Chen's 44 photos focus on the night and the day after of the student activists' occupation of the Executive Yuan, while the two Apple Daily reporters' works also include images of the police forcibly evicting the sit-ins during the occupation of the Executive Yuan.

The four sets of press photos are similar in content, focusing mostly on the occupation and sit-in of students and social activists inside and outside the Legislative Yuan, as well as the occupation on the Executive Yuan. The scenes inside the Legislative Yuan include the sit-in at the assembly chamber, the chairs and students blocking the entrance to the chamber, the various slogans, signboards, and food and water on the podium. There are also the close-ups of the occupying students, their facial expressions and photos of them resting, having meetings, making paintings, showing fatigue, falling sleep, massaging each other to relieve stress and other warm moments, and the final heroic exit. Of course, the portraits of the two leaders of the movement, Lin Fei-Fan and Chen Wei-ting, are not missing.

The street scenes outside the Legislative Yuan include the sit-in crowds with sunflowers and the sit-in in the rain; various support teams (medical, legal, supplies, etc.), various posters, billboards, slogans, various street close-ups or details; confrontations and tug-of-war between movement participants and those who were against the movement, water jets forcibly dispersing the crowd, the crowd of participants with cell phones glowing collectively, police officers on duty taking a break, taking a meal, the free sausage stand, etc. To capture the actions of occupying the Executive Yuan, there are photos of crowds gathering at the main entrance of the Executive Yuan, activists crossing the railings and breaking into the Executive Yuan building through the second-floor windows, sit-ins in the courtyard, police evictions and physical confrontations, forcibly dragging away students from the sit-in, and so on. The four photojournalists' photos are all of professional standard, each capturing many moments of conflict or touching scenes. Chang Liang-I of Apple Daily adopted black-and-white images to represent distinctive photos of empty scenes and quiet moments in the occupied area of the Legislative Yuan, while Hang Dapeng from the same newspaper made a relatively comprehensive coverage of the movement.

After carefully comparing and analyzing the news photos of four photographers from two major daily newspapers and comparing them with the photobook Before the Dawn which will be analyzed later, this article has the following findings. First, the news photos from both Apple Daily and China Times indicate that photojournalists of today’s Taiwan are capable of recording a passionate and combative political opposition movement in a relatively detached manner. Different from the photojournalists in the 1980s, who were simultaneously participants of the movement, these photojournalists have gradually returned to the stance of the tradition of professional photojournalism in the West, maintaining a distance from the movement to calmly observe and record. Secondly, although Apple Daily and China Times held very different political stances on CSSTA and on Chinese affairs, the four photojournalists of these two newspapers share similar approaches in their news photography. [79] This paper proposes two explanations for this finding: (1) in the face of news events of conflict and confrontation, the training of professional journalists first and foremost required them to capture dramatic moments and images at the scene of the event; (2) the photographers of China Times tended to view the significance of the Sunflower Movement positively, despite the newspaper’s political stance.

The first explanation is based on the analysis of the characteristics of Western photojournalism seen in the examples of the Pulitzer Prize-winning works and the information about the four photojournalists. The four groups of photographs have similarity and difference in their visual contents, but most of the works, no matter whether medium-length or close-up shots, always choose a dramatic visual focus to guide or grab the viewer's attention. This is often achieved by highlighting key figures in the scene through low-key lighting or a short depth-of-field. A common example is a young female student—holding a sunflower, with tears in her eyes, or with her head raised, smiling, or shouting—clearly standing out from the crowd of sit-ins or protesters around her, which becomes the visual focus in the centre of the “stage.” (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Participants of the Sunflower Movement. Photograph by Fang Jun-zhe from China Times.

Figure 5: Participants of the Sunflower Movement. Photograph by Fang Jun-zhe from China Times.The second explanation comes from the author's hypothesis based on the observation of the political "lineage" of Taiwanese photojournalists since the 1980s. I propose that, although China Times is clearly pro-China after being taken over by the Want Want Corporation, the team of photojournalists from China Times, led by the veteran photojournalist Huang Tzyy-Ming, who had witnessed the democratization movement and various struggles in Taiwan beginning in the 1980s, would not let the specific political stance of the newspaper compromise their ethics in using photography to witness movements for political resistance and social justice. This political ethic had been rooted deeply in the photojournalists of the generation of the raging democratic movement, whose passion for political reform and social issues was difficult to smother. The author believes that this passion, to some degree, has been absorbed and influenced the new generation of photojournalists.

This hypothesis was confirmed in the author's interview with Huang Tzyy-Ming, the head of the photography department at China Times.[80] According to Huang, before the photojournalists in his team set out to cover the Sunflower Movement, he clearly told them that, they should not set any limits when taking photos on site. Huang also found that the young generation of reporters on the photo team of China Times were generally in agreement or support of the students’ actions in the Sunflower Movement. The political stance of the newspaper did not have much influence on them. The print media in Taiwan, except for the newspapers and magazines belonging to the Next Digital Ltd. (Yichuanmei) from Hong Kong, have not really valued or understood the communicative power of photography for a long time. As a result, the photojournalists were regarded as an instrument for image production, but simultaneously such circumstances enabled them to maintain certain level of autonomy without much interference. [81]

5.2. The Image Theatre of Before the Dawn: The Sunflower Movement

As pointed out earlier, Before the Dawn is the most representative visual text among the many photographic records of the Sunflower Movement. According to the description of the photobook, Before the Dawn is produced through a fund-raising platform that collected both production costs and photos on the internet. The core editorial team assembled within a month $7,450,119 NTD and 13,000 photos from more than 800 photographers. The core editorial team itself, with a total of 17 members, was assembled through the internet. After four months of editing, 280 photos were selected to complete the book.[82] The book was printed in 30,000 copies and was not to be reproduced or reprinted. Therefore, although the print run of the first edition was relatively large by Taiwanese standards, the book became out-of-print as soon as it was published, which seems to have made it a precious memento or even a collectible.

This photobook of historic images, worthy as a collectible, compiles the photographic records of non-journalistic participants and observers of the movement. Eight hundred photographers had taken more than 13,000 photos, which, in addition to the repetitive contents or scenes, should have diverse and heterogeneous approaches and views. If they were scattered in the online space, they may have presented a relatively diverse visual landscape. However, when these photos were filtered into 280 pieces by the editorial team, the diverse landscape disappeared. In his analysis of the visual politics of the Sunflower Movement, Chang Shih-Lun argued that the visual production of the movement, when compared to the documentary photography before and after the lifting of martial law, generated a participatory aesthetic, which he called the “affective turn” and deemed a new visual paradigm of political protest images.[83] Chang then points out that this “paradigm” still relies on certain principles of traditional documentary aesthetics, such as the concept of the decisive moment, but “an aesthetic that emphasizes the participation of non-professionals, the priority of sensuality, and the omnipresence of the camera seems to become an unstoppable trend.”[84]

Chang’s observation that participatory photography with an “affective turn” is the new approach of photography in political struggle in Taiwan and is valuable and insightful. My previous analysis of American/Western practices of photojournalism has already revealed that photojournalism/documentary photography mainly relies on emotional appeal, which is testified by the aesthetic characteristics of realistic photography as well as its function in the market economy. In addition, my review of political resistance images in Taiwan in the 1980s also explains that photojournalists at that time played the dual roles of professionals and participants in the democratization movement, with the collective opposition against the authoritarian rule of the KMT as their internal motivation for making witnessing photography. However, according to Chang's observation, the quantity and sense of collectivity of the visual record of this movement is so unprecedented that it has become a new phenomenon, even though the active participation and emotional involvement in the production of images during the Sunflower Movement are slightly similar to the past practices. Chang states, “On the one hand, the photos and images shared on social networks are like a diary, witnessing the ups and downs of the events, which at times are mundane and quotidian and at times stirring and riveting. On the other hand, they could monitor the state power in real time, and could be used to call upon friends and people nearby in a near instant, continuously proposing new strategies of protest images. The affective, participatory photography also manifests in the large number of posters and protest slogans made by the people at the protest venues. They are more of an emotional and personal expression of ‘I have something to say.’”[85] These are the difference in emotional expression between the Sunflower Movement and the previous practice.

Building on Chang's analysis and a close reading of Before the Dawn, this paper further argues that this aesthetic of affective turn and the visual politics it constructs were effectively created through the editorial work of the photobook. In a word, the editorial team has produced a perfect “theatre of images.” This theatre on paper, built in the form of a book, diminishes its use of textual information to a minimum: only a small paragraph at the beginning and another one at the end, each with no more than 300 words. Even the page numbers of the book are discreetly printed in the lower right corner of each page, which would only emerge from the reflective surface when one finds the right angle. This design allows the images in the book to flow as smoothly and continuously as possible, without distraction from a certain “sense of source material” generated by the page numbering.

Of the 280 photos in the book, 139 black-and-white photos are used, interspersed so that colour and black-and-white photos each occupy half of the book. Given that cameras and cell phone cameras today are all able to take colour photographs, so many black-and-white photos, if not deliberately set by the photographers on their cameras or cell phones, is the result of the deliberate changes made by the editorial team to turn many of the original colour photos into black-and-white. When analyzing the standard mode of black and white photography preferred by the photographers in Magnum, I have already pointed out that black and white photographs with colour elements removed are more capable of abstracting the events and scenes for heightened visual and emotional effects. This also explains that even though Before the Dawn uses images of the non-professional participants, both the photographing and editing still reproduces the classical aesthetic concept of Western traditional photojournalism/documentary photography.

It is the photobook’s sequencing and titles dividing sections that nailed the design of Before the Dawn as a theatre. The table of contents demonstrates that the photographs in Before the Dawn are edited into a “seven-act play” similar to the form of ancient Greek theatre. The titles of these seven acts are: “Prologue,” “Nightfall,” “Dead of Night,” “Darkest Hour Before Dawn,” “Breaking Dawn,” “Departure,” and “Epilogue.” From “Prologue” to “Epilogue,” the editors wove the photos of the Sunflower Movement into a script with a closed and singular meaning, and a perfect and happy ending. There are no photos in the "Prologue" section, only two black pages, which, according to the text, are "the deep, dark night that pervades the island at an unknown time.” After the heavy darkness of the night and even darker moments, the dawn broke and the journey began. And the photobook concluded with the triumphal procession led by the participants who were to “sow the seeds of the next phase as you exit” (chuguan bozhong), the handsome photos of Lin Fei-fan and Chen Wei-ting (Figure 6), the crowds of supporters who filled Jinan Road to welcome the heroes, and the smiling face of a young woman who shed tears of joy. (Figure 7)

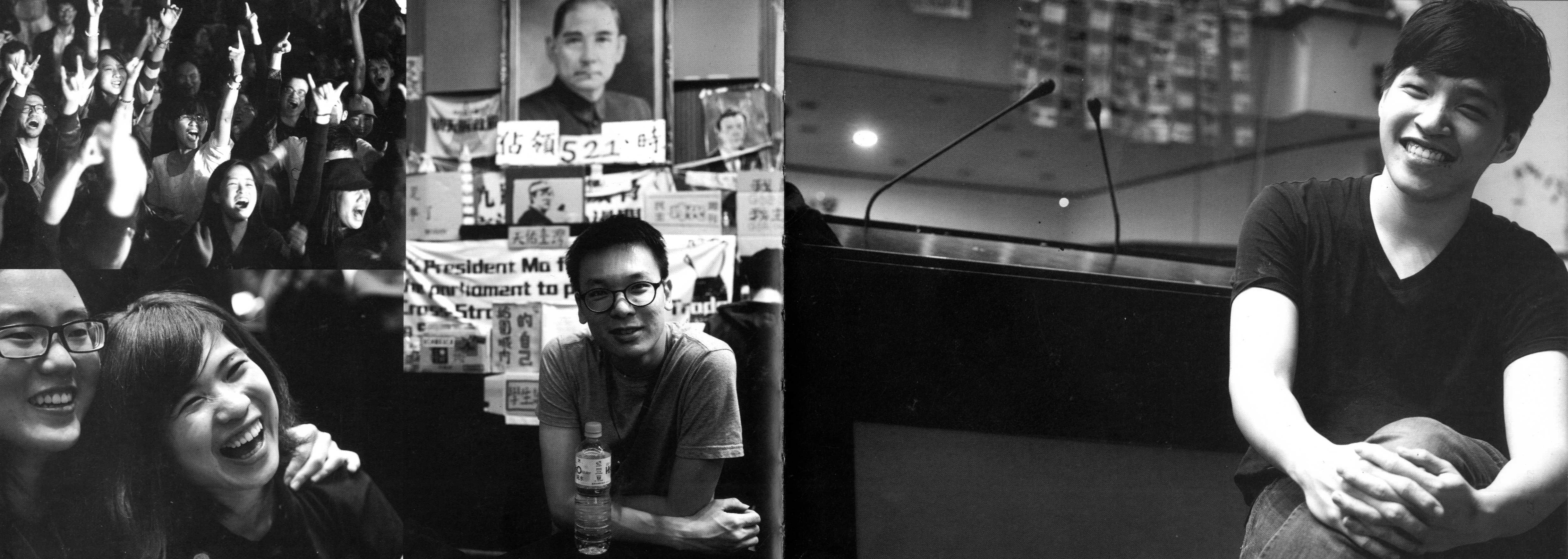

Figure 6: The leaders of the Sunflower Movement, and Lin Fei-fan and Chen Wei-tin. Photographer unknown. Published in Before the Dawn.

Figure 6: The leaders of the Sunflower Movement, and Lin Fei-fan and Chen Wei-tin. Photographer unknown. Published in Before the Dawn. Figure 7: The last photo in Before the Dawn

Figure 7: The last photo in Before the DawnThis coherent and self-contained image theatre of the Sunflower Movement inserts all the selected photos in its set up of a multi-act script. Although the order of the photos largely follows the sequence of the development of the events, the editors disregarded the chronological order of many photos and instead arranged them to serve a coherent story with theatricality. The story line of a singular meaning presents the process of the student activists taking the lead in occupying the Legislative Yuan and breaking through the darkness to welcome the light. (Figure 8). A consistent sense of theatricality comes from the various photographic moments chosen by the editorial team to appeal to emotion, passion, or sentiments. Under the editorial goal of a singular meaning and coherent emotional arc, the theatricalized photobook excludes all other visual materials that are not suitable for inclusion in the established story script, or the multifaceted reality of the protest scene.

Figure 8: Occupying youths who were climbing into the Legislative Yuan on a ladder. This photograph is used as the cover of Before the Dawn as a symbol of breaking away from darkness to move toward the light.

Figure 8: Occupying youths who were climbing into the Legislative Yuan on a ladder. This photograph is used as the cover of Before the Dawn as a symbol of breaking away from darkness to move toward the light. For example, Before the Dawn does not care about the pluralistic opinions at the "Pariah Liberation Zone" in front of The National Taiwan University Alumni Hall on Jinan Road outside the Legislative Yuan, or the voices of the “zone of slave labor on the second floor,” a dissident corner inside the Legislature Yuan. On pages 176 and 177, the editorial team symbolically included two photos from these two areas, the meaning of which are of great ambiguity: a masked protester in front of the "Pariah Liberation Zone" banner, raising his hand in salute to what is outside of the frame, which is unclear and lacks a meaningful context. The meaning of this photograph can be interpreted arbitrarily, as the caption mentions nothing other than the time and general location of the photo.[86] The photo taken from the "zone of slave labor" on the second floor of the council chamber shows the young occupiers in this area raising their arms and chanting together. It is impossible to know whether they are shouting for the movement, or supporting or protesting against the command centre on the first floor. With such ambiguity, the only two photos about the diverse voices from the scene of the movement are subsumed in this image theatre.

In the "Manifesto of the Pariah Liberation Zone" included in the appendix of This is Not the Sunflower Movement: 318 Movement, the co-founders of the zone did not want to “enable a peaceful and rational garden party where the power core could promote themselves rather than [launching] a collective and active struggle of the masses.”[87] They state explicitly that

This is not just a student movement. There are many more participants from all walks of life: workers, farmers, businessmen, office workers, and many more people of all stripes who are not seen as having the ability to make decisions about the movement. This group of people, all gathered in the Liberation Zone, tried to further develop a vision for the movement.[88]

Another statement, “Statement on the Withdrawal of Slave Workers from the Second Floor,” also emphasizes that this was not just a student movement, but “a people's action,” without which the occupation would not have been sustained. They, as a group of slave workers who had been enclosed on the second floor of the venue and were responsible for security and the flow of goods, but who had been “exiled for a long time to the periphery of the movement's power,” were deeply dissatisfied, therefore protesting against the decision of the leaders to withdraw from the venue without adequate communication.[89] Many of these people suffered “movement injuries,” but these voices and images are completely invisible in the image theatre of Before the Dawn, where there is only unanimous celebration.

Such an image theatre constructs a dichotomy of moral good and evil, simplifying the complex reality and pluralistic voices of the movement scene. This visual representation also coincides with a certain phenomenon of the Sunflower Movement: when the participants of the movement inside and outside the Legislative Yuan had very diverse and heterogeneous discussions or debates about the issues, methods, or basic ideas of the movement, it was difficult for these diverse opinions to appear on the main stage or the main platform. When discussing with the author about the experience of the movement, Qiu Yonan, a graduate student at the National Chengchi University who experienced “movement injuries” in two ways, observed the above phenomenon by taking the anti-China sentiment in the movement as an example. [90] He pointed out that the "China factor" and related issues were indeed discussed extensively at the sit-ins, and the views and opinions were quite diverse and in-depth; however, when it came to the main stage, China-related issues were quickly reduced to anti-China discourses or sentiments, and equated with anti-Marxism and anti-KMT.

In the later stages of the movement, Cheng Nan-jung's posthumous photo, portrait, and the repeatedly used quote "The rest is up to you" were posted at the sit-in, and a candlelight vigil booth, dubbed by Shih-Lun Chang as “a mini religious altar,” was set up by the participants of the movement.[91] (Figure 9) On the main stage inside the Legislative Yuan, Cheng Nan-jung's posthumous photo was also enshrined above the main podium, occupying the most eye-catching position right under the Portrait of Sun Yat-sen, the Founding Father.[92] (Figure 10) That such a ritualistic scene appeared in the Sunflower Movement and was photographed and included in Before the Dawn demonstrates the political nature of this movement as well as that of the image theatre. In this movement, the specific issue of anti-CSSTA has been equated to the anti-China and Taiwan independence movements. In the case of the image theatre, the sacred religious atmosphere in this photo reveals that, through these visual tropes, the youth of the Sunflower Movement indulged in self-righteousness, moved by themselves and sanctifying themselves.

Figure 9: The candle vigil for Cheng Nan-jung outside of the Legislative Yuan. Published in Before the Dawn.

Figure 9: The candle vigil for Cheng Nan-jung outside of the Legislative Yuan. Published in Before the Dawn.  Figure 10: After occupying the Legislative Yuan for 515 hours, the movement’s leaders held a news conference. Lin Fei-fan made a statement in front of the photo portrait of the deceased Cheng Nan-jung. Photograph by Hang Da-peng of Apple Daily.

Figure 10: After occupying the Legislative Yuan for 515 hours, the movement’s leaders held a news conference. Lin Fei-fan made a statement in front of the photo portrait of the deceased Cheng Nan-jung. Photograph by Hang Da-peng of Apple Daily. It is understandable that the young students who were never before called to participate in the sit-in and protests were moved by the impactful experience of participating in civil action. There is nothing to blame when they were overtaken by such emotions and collectively recorded it. However, the first and last essays of Before the Dawn elevate the issue of the CSSTA and the protests to artsy literary tropes such as "dark vs light" and "ignorance vs enlightenment." This paper argues that this simultaneously reflects a certain kind of simple, earnest, but ignorant passion of the movement participants and photobook editors, and the collective state of this generation's enthusiastic youth, who easily fall into self-pity and self-celebration. [93] In a world where the production and circulation of images and other information are commonplace, the dramatic "visual logic of dichotomy" and the "overly cheap interpretive framework" of participatory photographs are no longer politically enlightening and therefore unnecessary.[94] Before the Dawn presents a narrative about the Sunflower Movement that is celebrated and turned into a spectacle by images, in short, an image theatre. It demonstrates the hegemonized emotion and understanding of the participants.

6. Conclusion: Photography, Social Movement, and Political Reality

In the "Manifesto of the Pariah Liberation Zone," there is the following paragraph:

At the site of the movement, although we are active and dedicated, we do not have the right/power to participate in a common decision. The movement appears to be collectively shared, but in reality, everything is led and decided through a few decision makers, as usual. The leading voice and ruling method reproduced the existing system of representative democracy, and likewise resorted to the so-called rational and peaceful means of governance. This reproduction stemmed from a lack of imagination of action by those at the heart of power, and a disconnect from the realities, aspirations, and motivations of a pluralistic population—just as the political system we now oppose.[95]

Hsieh Shuo-Yuan, one of the co-writers of this manifesto, describes his observations after two weeks of participation in the movement in another article. For him, "the meaning of a social movement is not only whether the demand is achieved or not, but also on what ideas are ‘overflowing.’” He believes that if the anti-CSSTA movement can be carried out in a bottom-up manner, it will "rethink the current logic of the capitalist system,” no longer allowing power and capital to dominate people. This will enable the movement to consider not only immediate results but also a longer-term vision.[96]