Disobedient Photobook: Photobooks and the Protest Image in Contemporary Hong Kong

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

In a book published in 2017, Hong Kong-based writer Antony Dapiran dubbed Hong Kong a “city of protest.”[1] Since the Handover of Sovereignty in 1997, Hong Kong has witnessed growing grassroots and civil protests and civil disobedience activities that directly engages the changing political reality.[2] The political situation and civil disobedience in Hong Kong was intensified in recent years. From 2019 to 2020, many large-scale citywide protests and civil disobedience activities happened in Hong Kong in response to the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019—controversial because of its extradition provisions from the HKSAR to the People’s Republic of China, among other countries. The protests therefore are known as the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Protest (2019-20). The 2019 protests attracted many photographers, both locally based and those from other parts of the world, who came to Hong Kong for assignments, personal projects, or simply to witness or participate. More importantly, in parallel to the unfolding of the protests was an unprecedented boom in the creation and publication of photobooks.

Since 2019, the infrastructure for photobooks has been well developed in Hong Kong, which can be seen in the boom of independent publishers and self-publishing, a photobook fair and festival, photobook competition and touring exhibition, and crowdfunding as project financing. The First Hong Kong Photobook Festival was launched in April 2021 with programmes such as a photobook survey exhibition, a book dummy competition and exhibition, seminars, and a photobook market.[3] As previous studies on photobooks in China and the greater Sinophone world have already shown, photobooks are products of the “political, economic and cultural conditions of the society [in which they are created]” and their sudden rise often corresponds to major historical changes.[4] Even though photobooks can be regarded as a slow, even stubborn, medium in the environment of rapidly changing political situations in Hong Kong—and the ever-evolving media landscape in the age of information globally—the making of photobooks of and as protest is, I argue, a disobedient resistance to the local milieu and global information flow that requires scholarly attention to examine its importance in contributing to the larger visual culture and cultural production of civil disobedience and protest images.

This article offers a thematically-organized analysis of Hong Kong’s photobooks. This research mainly draws from photobooks from the reference library at Lumenvisum, an independent photography space in Hong Kong, where the author curated an exhibition, Unfolding Hong Kong: Photobooks Collection from Lumenvisum (Hong Kong, April 2021).[5] My study of these photobooks and their creators are based on semi-structured interviews through social media or face-to-face meetings. These recent endeavours in photobooks are contextualized in the longer history of photobooks of protest images, especially photobooks on the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, which were made either by Hong Kong photographers or published in Hong Kong. As Hong Kong photobooks and protest images have yet to receive scholarly attention, this article provides much-needed study on individual projects as well as the local development of photobooks and independent publishing. While the relationship between photobook and protest image has been discussed in other contexts in Asia, this article engages with the notion of disobedient photobooks in Hong Kong when the city is rapidly losing civil rights despite its residents fearless and persistent protests.[6] In that sense, this article hopes to become part of the larger endeavour to preserve visual materials of increasingly unspoken subject matters.

Transborder Observations of Local Movements

During the 2019 protests, photographers from all over the world travelled to Hong Kong, documented major political events, and published their works outside Hong Kong. The majority of these works fall into the traditional mode of photojournalists. In addition to the standard global production and circulation of news photography is the phenomenon of photobook publication by photographers of neighbouring regions and nations, whose proximity to the protest, both geographically and in terms of a shared experiences of recent history, led to a more immersed point of view. This transborder observation also played a particularly important role when local political pressure and press censorship prompted photographers to seek ‘safer’ ways to get the visual and cultural productions out of the locality and publish it beyond the border.

Figure 1: Covers of Hironori Kodama, Block City (Kyoto, Japan: KungFu Camera, 2020) and Hironori Kodama, New City (Kyoto, Japan: Hironori Kodama, 2020).

Figure 1: Covers of Hironori Kodama, Block City (Kyoto, Japan: KungFu Camera, 2020) and Hironori Kodama, New City (Kyoto, Japan: Hironori Kodama, 2020).Japanese photographer Hironori Kodama (b. 1983) published two photobooks Block City (2020) and New City (2020) in Japan, after spending ten months in Hong Kong to witness the 2019 protests. (Figure 1) Both books consist of more than 100 colour photographic images each, but they document the 2019 protests in two drastically different ways. New City covers reportage photography of major events in the 2019 protests whereas Block City thematically includes different types of roadblocks created by protestors, from bricks to umbrellas, bamboo scaffolding to crowd control barriers. Block City captures the ephemeral traces and aftermaths of the civil protests that occurred but soon disappeared through the depiction of still-life like objects (as the book title in kanji—Chinese characters incorporated by the Japanese language— jingwu 靜物 ‘still-life’ suggested).(Figure 2) Each of the blocking objects and tactics is annotated with their nature and location to provide an overview in an almost encyclopedic style. The first editions of both photobooks are now out-of-print.[7] The first theme of disobedient photobooks in Hong Kong is characterized by the notion of transborder observation of local political movements. Another example of a Japanese photographer producing photobooks that documented the 2019 protest is created by Takehiko Nakafuji. Nakafuji adopts black-and-white photography, a more classical approach and aesthetic in the tradition of concerned photography in documenting social injustice and trauma. Consisting of 104 black-and-white photographic images, Hong Kong 2019 (2020) follows a more poetic approach by documenting not only the protest but also the everyday lives of the people of Hong Kong, in the fashion of Robert Frank’s The American (1958).

Figure 2: A page from Hironori Kodama, Block City (Kyoto, Japan: KungFu Camera, 2020).

Figure 2: A page from Hironori Kodama, Block City (Kyoto, Japan: KungFu Camera, 2020).The contemporary transborder observations of local movements, which led to the making of photobooks, resemble earlier moments, especially the June Fourth Incident of 1989. The student protest in 1989 anchored in Tiananmen Square in Beijing is one of the largest protests in twentieth-century China, which was witnessed by the world through mass media coverage. Although the Open Door Policy championed by Deng Xiaoping was established in 1978, it remained difficult for foreign correspondents, journalists, and photojournalists to have access to China. Foreign journalists had to seek formal approvals and work permits from the Chinese authority and/or informally through guanxi (connections).[8] Despite the difficulties and restrictions, photojournalists made great efforts to reveal truth through their camera lenses. Iconic images from the Tiananmen Massacre, for example the ‘Tank Man’ (1989) often attributed to Stuart Franklin (Magnum), circulated through wire news services and the Internet, which were later appropriated in contemporary art projects both within and outside of China.[9] To create a photobook, Franklin published Tiananmen Square (1989) with Black Sun, a private publisher in London, UK. Compiling colour photographs of the massacre in a 24-page large format, saddle stitch bound booklet, including images of icon, hero, chaos, and the aftermath of the Massacre, Franklin’s approach in Tiananmen Square aimed at creating a grand narrative from the view of a mainstream media practitioner for the mass audience in the EuroAmerican context.[10] The work adopts the classical approach and tactics of reportage photography to present a grand narrative of the Tiananmen Massacre. Because of this, the publication could also be read as Eurocentric in the sense that it provides a visual narrative of what a Western audience would anticipate seeing: “good against evil, young against old, freedom against totalitarianism.”[11]

In sharp contrast, photographers from Hong Kong and China who experienced and witnessed the Tiananmen protests and the June Fourth Massacre in 1989 took different approaches in terms of photographic style, conceptualization, and narration. Hong Kong photographer Wong Kan Tai (b.1957) first published ‘89 Tiananmen (1990) with the Limen Publishing Company in Hong Kong, then a second edition with Hong Kong’s independent publisher Mahjong Publishing in 2011. In the late 1980s, photojournalists from Hong Kong took advantage of geographical and geopolitical proximities and frequented China to cover news. Wong worked as a photojournalist for Wenweipo, a pro-China newspaper in Hong Kong. In 1989, he temporarily left his job, travelled to Beijing, and documented the Tiananmen Massacre as a personal project. The 1990 edition of ‘89 Tiananmen contains 71 black-and-white photographic images and provides a personal and intimate narrative of a photographer’s visual journey that was not necessarily meant for immediate mass communication that would arouse media sensationalism. A clear distinction can be seen between photography projects that are professionally related (for example Franklin) or personally driven (that is, Wong): Franklin’s portrayal of the Tiananmen Massacre presents a series of iconic and informative images to serve the purpose of communication for mass media. For Wong, the ‘89 Tiananmen project captures personal experiences and encounters. Wong immersed himself in the everyday life of the student protesters in Beijing, a process similar to participant observation in anthropology, which can be seen in images such as ‘An impromptu birthday party for one of the students in the square’ (plate 31) and ‘A student of Beijing University with his head shaved to show his discontent’ (plate 58). The ethnographic details are rich and dense, and ideally the two approaches by Franklin and Wong complement each other constructively for the understanding of the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989.

In addition to Wong Kan Tai’s ‘89 Tiananmen, which is an offset printing photobook published and distributed by independent publishers in Hong Kong, handmade photo albums of the Massacre can also be found in the library at Lumenvisum.[12] For instance, Hong Kong photographers Tse Ming Chong and Tam Hong Ming made 1989 We Will Not Forget (1989), a postcard album of photographic images from Tiananmen Square before the June Fourth Incident.[13] Tse Ming Chong worked as a commercial photographer at the time. He learned about what happened in Beijing through mass media in Hong Kong and felt compelled to witness what was happening there. Eventually, he travelled to Beijing in May 1989 with a Mainland Travel Permit with Tam. The Mainland Travel Permit allows Hong Kong and Macau photographers to travel to China and take up assignments without proceeding to further immigration paperwork or a work visa. At the end of his brief visit to Beijing, Tse returned to Hong Kong with three rolls of black-and-white film and colour slides as a conclusion and visual testimony of the visit, right before the outbreak of the June Fourth Incident. 1989 We Will Not Forget therefore offers a glimpse into the days before the June Fourth Incident, a typical, stagnant, and stuffy Beijing summer. The postcard album contains only 10 colour photographs by the two photographers. The sequence of 1989 We Will Not Forget starts with the portrait of Chairman Mao hung above Tiananmen taken at night, which is one of the most iconic photographs by Tse Ming Chong (Figure 3), then proceeds to some rather calm and uneventful depictions of student protestors’ activities at the Square. A handmade postcard album with two editions, 1989 We Will Not Forget stands far apart from journalist photographs for the wire news services. It can be read as a critique to mass production and reproduction of photography and images of the twentieth century. One of the surviving editions, now housed at Lumenvisum, has its own historical significance in preserving and supplementing the grand narrative and popular accounts of the happenings of the June Fourth Incident.[14] Other ephemerals published by Hong Kong’s mainstream mass media can also be found in Lumenvisum’s archive, including special issues by Sing Tao Publishing and City Magazine.[15]

Figure 3: Tse Ming Chong and Tam Hong Ming, 1989 We Will Not Forget (postcard album, 1989).

Figure 3: Tse Ming Chong and Tam Hong Ming, 1989 We Will Not Forget (postcard album, 1989). These photobooks and visual documents testify to the unique role transborder observations played in the production and dissemination of protest images and the unique position of Hong Kong before the Handover of Sovereignty in 1997. Transborder publishing provides an opportunity for the challenging environment in photographing and publishing politically sensitive subjects in the contemporary Chinese context. Given Hong Kong’s current political conditions, the photobooks and the circumstances of their production offer a poignant reminder of the geopolitical distinctiveness of Hong Kong, and its place and relation to China and the rest of the world. The Japanese photographers’ engagement with the 2019 protest demonstrates how protest images were created with inter-Asian networks, which calls attention to a more intimate approach driven by the concerns of photographers in relation to the location of the protests as well as their reflection on the political conditions in their own home bases.

Seeing and Obscuring in Photobooks

Clean Hong Kong Action (2019), a photobook in a concertina format handmade by Siu Wai Hang (b. 1986), features photographs of hundreds and thousands of protestors, whose faces were represented by cut-out holes.[16] (Figure 4) This technique of hiding identity through deletion of faces replaces more common methods, such as pixilation, with holes that carry a powerful connotation of emptiness and erasure. This highly-original photobook epitomizes the tension between representing and obscuring heightened in the works of many Hong Kong photographers, who often had to adopt more conceptual approaches as alternative tactics to protest against state/self-censorships.

Figure 4: A page from Siu Wai Hang, Clean Hong Kong Action (photobook dummy, 2019)

Figure 4: A page from Siu Wai Hang, Clean Hong Kong Action (photobook dummy, 2019)Clean Hong Kong Action can be understood as a response to and intervention of Hong Kong pro-establishment politician Junius Ho’s advocacy “Clean Hong Kong Campaign” in the latter half of 2019.[17] Ho’s proposal was to destroy all Lennon Walls in Hong Kong to keep Hong Kong “clean.” Cleansing, in the local context however, has multifaceted meanings due to political-ideological differences from the spectrum of purification to annihilation. The creative intention behind Clean Hong Kong Action was thus begun from the ambiguity of meanings and presence. The photobook consists of a handful of black-and-white photographs of citywide protests in Hong Kong in 2019, which are arranged in a chronological order – starting from the first citywide protest in June 2019 and ends at the last protest in December 2019. In addition to a linear arrangement, photographs are layered and superimposed in order to create an impression similar to what is experienced by witnesses and participants in the protests. Using a point-and-shoot film camera, Siu produced visual evidence of the protests in its most spontaneous manner, sometimes even without looking into the viewfinder to find a composition. The lightweight handheld point-and-shoot film camera could also be regarded as an earlier generation of mobile phone camera that is accessible to laymen. Clean Hong Kong Action captured the 2019 protests from the protestors’ point of view rather than journalistic or documentary perspectives. The images, therefore, belong to and construct the collective memory of millions of Hong Kong protestors, especially those described and classified as the ‘peaceful, rational and non-violent’ protestors (commonly known as the ‘yellow camp’), in contrast to the pro-establishment ‘blue camp’ and the more radical ‘black bloc’ dressed in black clothing and concealing their identities with face masks.

Siu describes the technique he used in Clean Hong Kong Action as “photography with holes.”[18] The photographic images were manipulated by hand: thousands of holes were pierced through the image by the photographer using a leather hole puncher. The action is meaningful, significant, and symbolic in many regards. For the photographer, it is an action of violence by forcefully destroying the photographic images, releasing agony and at the same time achieving an artistic effect. Moreover, the action of punching is a way to destroy and hide the facial features, and therefore identities, of the protestors in the images. Such deletion becomes a way to protect the anonymity of protestors. The punched holes also look like bullets have pierced through the paper, a visual metaphor of civil resistance against oppression and violence by an authoritarian regime.

This artistic intervention addresses the very polarised political situation and public opinions in Hong Kong. Unlike other photobooks that portray protestors as protagonist (or antagonist) in the protests, in Clean Hong Kong Action the mass is rendered into thousands of empty holes that traverses both sides of the concertina book. One can imagine these empty spaces as cut-out standees for photo-ops in an amusement park or in a commercial mall. The reader will be able to imaginatively place themselves, or their heads, into that empty space and be part of the protest. The photographer also suggests that the creation of holes is a process similar to hunting. He first placed the concertina book on a table, had the punching tool ready, looked for face, and started punching. The manual process is extremely repetitive and time-consuming. However, as the photographer claims: it became almost a therapeutic process. The photographer’s activity of punching was not planned or regulated. As a result, each edition has its variation in terms of size and position of the holes. The photographer kept looking for faces to delete, which served as a close reading and re-examining of his own work. The action was completed when there was no space left for hole punching.

Siu’s work reminds us of an earlier example by Beijing artist Xu Yong (b. 1954), who gave a conceptual twist to images of protest that he took in Tiananmen in 1989. Xu published Negatives: Scans (2014) which contains film negative images of snapshots of the Tiananmen protest in 1989. The negative images are not a denial of the historical and political event, but unlike photojournalistic accounts, they express a hesitation to publicise scenes and images of what happened at Tiananmen 25 years ago. Readers can render a mental positive image with imagination. The indirect and interactive seeing of truth is indeed a subversive and disobedient act to the totalitarian regime. What is intriguing about Xu Yong’s Negatives is that the book was never published in China and is only accessible outside China.[19] Voices and images of dissent from the official account of the Chinese political authority are prohibited there. Hong Kong was an exceptional case. A port city at the edge of China and a British colony before 1997, Hong Kong was a ‘window’ to see into and reach China. The freedom of speech and press granted by Hong Kong’s common law and legal infrastructure allows Hong Kong to be a safe port for Chinese disobedient or politically sensitive materials to be published and distributed in a Chinese city.[20] Moreover, it is prohibited to mail unofficial publications from Hong Kong to China. Xu’s example demonstrates again how the making and publication of photobooks transgressed geographical and judicial borders for survival and dissemination. Moreover, in order to survive and avoid control and censorship, visual material must be executed in a creative manner. Obscuring seeing is one of many creative strategies and other examples will follow here.

Concerned Photography and Empathy

The 2019 protests in Hong Kong were not a sudden outbreak but the crest of on-going protests of almost two decades. On July 1, 2003, large number of Hongkongers marched to protest the anti-subversion Hong Kong Basic Law Act 23. The incident marks the beginning of the culture of public and civil protests in Hong Kong. An increasing number of public protests have occurred in Hong Kong ever since. In 2009 and 2010, the Anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link Movement protested the highspeed rail network connecting Hong Kong and China, which epitomized the local sentiment and desire to detach Hong Kong from China through grassroots social movement. In 2012, a citywide protest happened in Hong Kong to oppose the implementation of moral and national education.[21] In 2014, the Occupy Central and the Umbrella Movement put Hong Kong on the map of the global civil disobedience movement. The rise of large-scale civil protests offered opportunities for photographers to capture and create visual history. Several reportage photobooks were published, for example, Hong Kong photographer Tam Chi Wing published We are NOT a Mob (2015) with Hong Kong independent publisher Four Elephants Publishing; and Ho Siu Nam (b. 1984) published Good Day Good Night (2015) with Brownie Publishing in Hong Kong. Thematic photobooks that may take a longer time to conceptualise and create become visible and viable in the decade of protests.

During this period one of the most exemplary projects was made by Hong Kong photojournalist Paul Tak Ming Yeung; his photobook Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir (2016) was published by independent publisher Brownie Publishing. The photobook was designed and printed in Taiwan, and distributed in Taiwan and Hong Kong. The project first started while the Anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link Movement was taking place in Hong Kong in 2009. Yeung observed that an increasing number of civil protests were happening beginning in 2009; concurrently, the Hong Kong Police Force was more involved to maintain public order. He thus turned his camera from photographing the protest to the everyday action of the Hong Kong Police Force.

Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir contains more than 100 colour photographs depicting the Hong Kong Police Force in a satirical and ‘humanised’ manner from 2009 to 2014. Yeung is known for his distinctive style: the use of flash, the capturing of bold colour and the humour of city life and the city dweller. This Martin Parr-esque pictorial style does not stop at being an aesthetic strategy to compose a picture but also approaches creating content and subject matter. In the opening sequence of the photobook, the Hong Kong Police Force was treated with sexual humour through the eyes of the photographer. (Figure 5) Political satire and visual commentary, which have a long and rich tradition in Hong Kong popular culture, gained new momentum in recent decades. Yeung’s project can be viewed as grassroots propaganda aspiring to influence public policy from below.

Figure 5: Cover and a page from Paul Tak Ming Yeung, Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir (Hong Kong: Brownie Publishing, 2016.)

Figure 5: Cover and a page from Paul Tak Ming Yeung, Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir (Hong Kong: Brownie Publishing, 2016.)The photobook project was financed by crowdfunding, one of the first of such attempts in the Hong Kong independent publishing scene. With the assistance of the publisher, the crowdfunding scheme eventually met its goal to cover the printing cost through an online payment platform. The scheme itself was also strategized as a visibility and outreach campaign. Crowdfunding has gradually become a viable and feasible financing model for independent photobook publishing in Hong Kong, East Asia and beyond, as in, for instance, The Year of the Awakened project in 2020 and Lam Yik Fei’s Woh Yuhng that will be mentioned later in this article.

The process of crowdfunding requires creators to communicate with backers to promote the photobook as well as ascertaining the anticipation and reception of the public. Paul Yeung received both supportive and critical comments on Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir. Some claim the photobook is a ‘disgrace to police’ while others applaud it as a humanised portrayal of the working life of the Hong Kong Police Force. Yeung explained this is how visual puns work in photography. Visual puns open ambiguity that enables multiple interpretations. Policemen in general are perceived as forces more powerful than ordinary citizens, often male-chauvinistic and even misogynistic. The sexual humour created about the Hong Kong Police Force in Yeung’s photobook on the one hand is cliché, yet on the other hand this depiction helps to soften the stereotype of the Hong Kong Police Force. We may view Yeung’s portrayal of the Hong Kong Police Force as neither a demonization nor degradation but humanisation.

In Yeung’s photobook, policemen’s identities are intentionally concealed as the photographer erased all the identification numbers on their shoulder badges with PhotoShop. The photographer explained that the erasure is meant to protect the privacy of individual policemen. Yeung emphasised that the PhotoShop manipulation is by no means to normalize white terror or to internalize fear, but a way to secure anonymity for the future. Under the current National Security Law in Hong Kong, the erasure protects both the photographed and the photographer. However, to resist self-censoring, the photographer listed all numbers and identities at the end of the photobook and arranged them in an illegible manner. Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir concludes with a self-portrait of the photographer himself as a self-mockery, which raises more questions for readers: is it all about satire and poking fun at some individuals by another individual, and not by a figurehead or of a state machine? Or is it a call for all of us to reflect on the nature of coercive force of a state and its relationship to citizens?

Hong Kong photojournalist Lam Yik Fei (b. 1986) published Woh Yuhng with Brownie Publishing in 2020. The 2019 protests demonstrate a new hybrid form of protest movement: be water, do-not-split, and being ‘peaceful, rational and non-violent.’ As the photobook title epitomizes, "woh” means “peaceful protestors” and "yuhng” means “the valiant.” Woh Yuhng includes 60 colour photographs depicting the process of the 2019 Protest in Hong Kong that focuses on the protestors, the police, and their actions. As a photojournalist working for the New York Times, Lam frequented the frontline to capture the battlefields. Depictions of chaos, conflict, and struggle are inevitable. However, I would in particular like to draw reader’s attention to Woh Yuhng’s book cover image—it describes one of the unforgettable moments of the 2019 protests when the crowd of protestors cleared the way for an ambulance to go to an emergency scene outside the Central Government Complex at the Admiralty like the biblical image of Moses parting the Red Sea. The image encapsulates the spirit of the 2019 protest and the very idea of empathy and concerned photography. The 2019 protests in Hong Kong are responses to the urge for democracy in the contemporary Chinese context, and actions resulting from that urge and desire are multifaceted. What has been of importance and the driving forces behind these actions are not intended to be aggression and violence by nature. The humanized power figure, the non-identification, and the utopian scene of the “sea-parting” shown in photobooks by Hong Kong photographers are snapshots to resist and counteract the world’s fast media and its widespread sensationalism in their visual representation of the 2019 protests. Photography is therefore not a tool to rebel. Instead, the creation and editing of photobooks is a way to reason and justify action. Disobedient photobooks and civil disobedience should not be understood as destructive forces. The constructiveness and the thought-and-heart put into the making of a disobedient photobook in Hong Kong should be acknowledged.

Rethinking Photographic Medium and Materiality

In addition to the thematic approaches discussed in the previous sections, some Hong Kong photographers’ engagement with the 2019 protests prompted them to rethink the photographic medium and the materiality of the protest image in book formats. Chan Kai Chun’s Gaze (2021) is a photobook dummy resulting from two exhibitions respectively at the KG+ SELECT programme, Kyotographie, Japan and then Lumenvisum, Hong Kong. Gaze is a portrait series documenting unnamed Hong Kong protestors, precisely the ‘black bloc’, during the 2019 protests. A particular style had been developed in portraying the black bloc in the 2019 protests in works by both local and overseas photographers: the protestors are often equipped with protection gear and face masks to describe their actions and protect their identities, and the photographic subjects are set against black or dark backgrounds.[22] When asked why he photographed unnamed protestors wearing face masks or protective gear against a dark background, Chan stated that this way of depiction enabled him to foreground the development of the protest action in Hong Kong. At first, the protestors did not always wear face masks, but gradually they all covered their faces to hide identities due to the tightening of the law and the intensity of actions. Eventually, the only thing we could see of the faces of the protestors was their eyes. It is exactly the eye contact that left the deepest impression for Chan, which reminds one of Alfredo Jaar’s work The Eyes of Gutete Emerita in The Rwanda Project (1994-2010).[23] Gaze was started in July 2019 and to date 81 protestors were photographed. A closer look at the sequence of Gaze would reveal that protestors who appeared at the beginning of the photobook were less equipped and covered than the protestors in the latter half of the photobook, which reflects the worsening oppression and violence as the 2019 protests progressed.

The photographic portraits in Gaze resulted from two exhibitions. Each portrait is composed of layers of images. Chan first took a portrait of a protestor, often a headshot, to capture the physical, mental, and psychological status of the person. Then he brought an aluminium plate to protest sites and added relief and texture to the plate by hitting and rubbing it with objects such as bricks. Finally, Chan printed the portrait on the aluminium plate in the darkroom as an artwork. (Figure 6) The juxtaposition of a portrait and visual texture on an aluminium plate created a photo-object of a memorial-like image. At the exhibition in Kyoto, 37 prints were shown and in Hong Kong, 27 of them. Chan intentionally placed the original aluminum photo-objects on the floor in the exhibition venues to demonstrate the rubbing process. Visitors can touch the work physically, feel the temperature of a metal surface and may as well leave their fingerprints on the metal surfaces. These traces on the photo-objects added layers of human touch to the work and eventually transferred the physical quality of the work to the photobook.

Figure 6: A page from Chan Kai Chun, Gaze (Photobook Dummy, 2021).

Figure 6: A page from Chan Kai Chun, Gaze (Photobook Dummy, 2021).These photographic objects were then rephotographed into images and compiled into the photobook, along with the feedback and commentaries on individual portraits from the viewers as well as the sitters collected at the exhibitions. Gaze is a horizontal format handmade photobook and is one of the largest photobooks discussed in this article. The photobook is bound by the Japanese bookbinding method in order to maintain the life-size headshot in the book format and the special appeal that this book format evokes. The photographer considered this as a tribute to deadpan portrait photography. Size and scale are important attributes in formulating a topology of people and protestors.

Like some artistic methods mentioned above, the rubbing overlaying the portraits of protestors was to protect their anonymity. As mentioned earlier in the article, while photography generally is a visual medium to reveal, one characteristic of disobedient photobooks is to employ photography and creative tactics to conceal. Similarly, the fear of publishing and publicizing artwork related to protests in Hong Kong has intensified after the introduction of the National Security Law (2021) and the related sedition law. These measures surely affected the public appearance of Chan’s Gaze project in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong exhibition happened after the introduction of the Law, many protestors and their families’ members were afraid to appear in public. To avoid jeopardizing protestors and to prevent their portraits being used as evidence against them, the photographer had to remove a few pieces and only exhibit 27 portraits in Hong Kong. Gaze, the photobook, is aimed at an edition of fifteen copies and it must be ordered by printing-on-demand. The idea of printing-on-demand photobooks over mass production and offset printing is significant, as this measure would control its dissemination. It is a safety precaution to protect the photographed, as only the printer and the photographer may know who the book will be delivered to. It is also a way for quality control because of the technical complexity of making the photo-objects.

While Chan Kai Chun’s work acts to capture the black bloc protesters in action, Wound of Hong Kong (2020) by veteran and award-winning Hong Kong photojournalist Ko Chung Ming traces the aftermath of action: trauma.[24] Although this series was shortlisted for the Sony World Photography Awards 2020, due to political censorship, part of the series was removed from the Award’s website before it was launched. As Hong Kong photojournalist Paul Yeung, whose work is also featured in this article, noted in his essay ‘Trauma and Photography’ in Wound of Hong Kong, this body of work constitutes not only portrayal of the protestors but also the post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma in general in the collective memory of Hong Kong people through a psychoanalytical approach.[25] Photography and trauma has long been a central topic in the tradition of reportage photography, be it photographing a traumatic event or the witnessing, reading, and feeling traumatised by photography.[26] Ko turned his lens to the aftermath of mass protest and violence to portray the wounds on the protestors’ bodies and through that to signify the wounds of Hong Kong. The success of Ko’s portrait series internationally and its popularity in Hong Kong may explain a citywide traumatic experience of creating and consuming the protest imagery. Contrary to traditional photobooks which are image-driven, Wound of Hong Kong puts equal emphasis on image and text. Photographer Ko Chung Ming collaborated with writer-cum-journalist Choi Wai Man. While Ko provided portraits of ‘black bloc’ protestors, Choi conducted interviews and narrated stories of some Hong Kong protestors. The 24 protagonists featured in Wound of Hong Kong are known from their involvement in the mass media coverage in the 2019 protests, for instance, Raymond Yeung, the Liberal Studies teacher at a local secondary school who almost lost his sight during the June 12th protest at Admiralty, and Sze Hon Hang (a.k.a. Kitchen Guy), a protestor in charge of the canteen who provided food for hundreds of student protestors at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University occupation in November 2019. Ko and Choi worked together to carefully curate this selection.

I would like to conclude this article by introducing Thomas Lin’s recent photobook 2020-1841 (2021).[27] (Figure 7) The book was started in 2017 as a personal project, when Lin became fascinated by Hong Kong’s historical photographs. Lin observes that the Umbrella Movement (2014) marked a beginning of Hongkongers deliberately making history photographically visible, or even photogenic. His project is not driven by a particular genre nor concept, but a desire to create a set of historic pictures of contemporary Hong Kong for the future. 2020-1841 reveals the ethos of disobedience in photography and photobooks of contemporary Hong Kong in two ways. Firstly, in the process of involving oneself in the protests and in photographing the protests, Hong Kong photographers resonated with the widespread yearning among Hongkongers to hold their faith and fate in their own hands. This has prompted photographers to explore and embrace a sense of self-determination and self-discovery in politics as well as in their exploration of the medium of photography. Hong Kong was conceived on the world map as a British colony in 1841, approximately the same moment when photography was invented in Europe. The earliest photographic images of Hong Kong were often made by Western photographers, for example John Thompson, Milton Miller, and G. E. Petter. The images were then exported to the West for foreigners to imagine the exotic Orient.[28] Hong Kong as a ‘foreign vision’ is now transformed to a local expression. The many photographers discussed in this article adopted innovative methods to challenge the traditions of journalistic, documentary, and humanist photography and to push the boundaries of photography in its materiality.

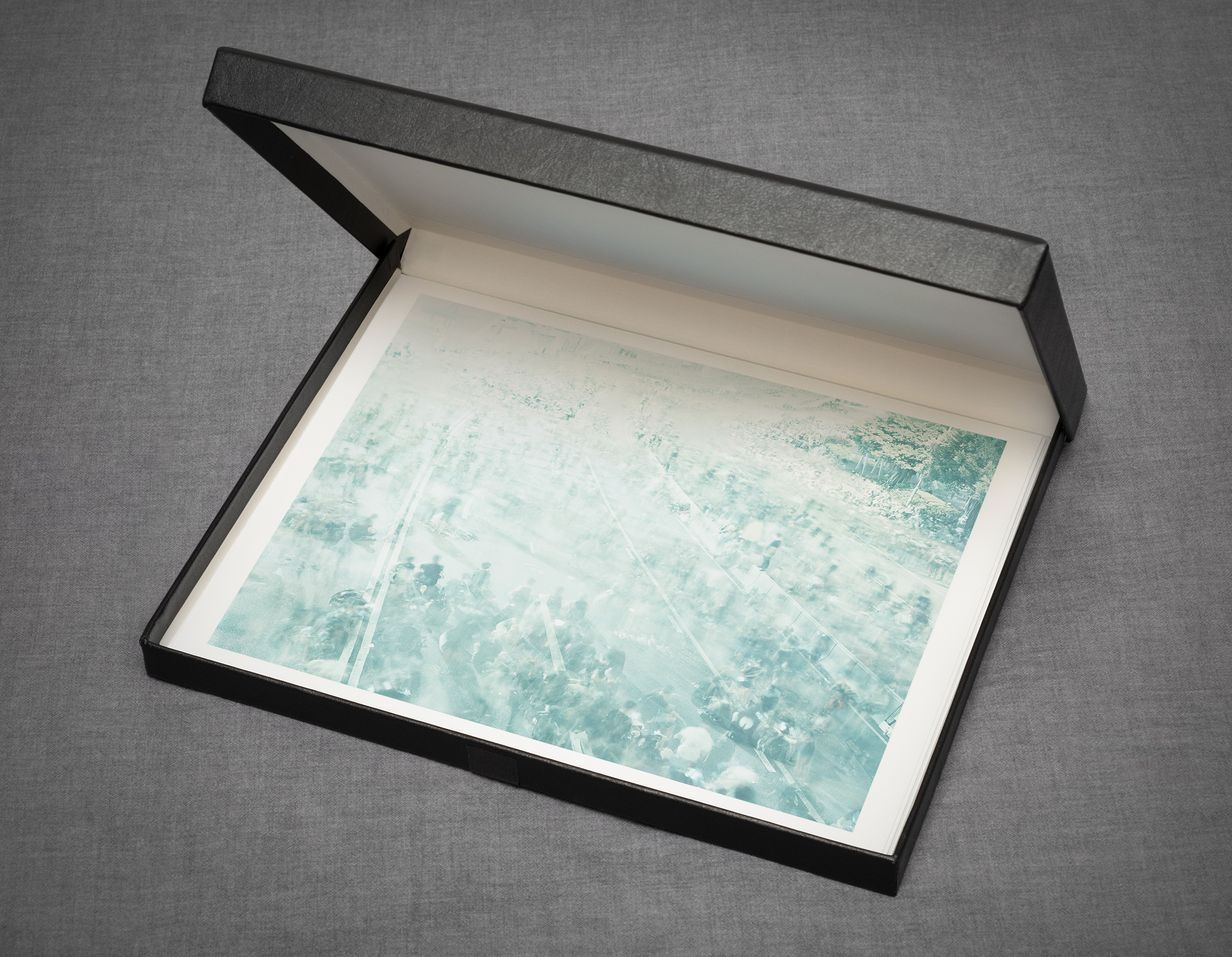

Figure 7: Thomas Lin, 2020-1841 (Photo Boxset, 2021).

Figure 7: Thomas Lin, 2020-1841 (Photo Boxset, 2021).Secondly, the photographs in the boxset collection are digital C-type prints.[29] A digital C-type print is made with both analogue (C for ‘chromogenic’ print as colour printing in the darkroom) and digital means (through a digital exposure system to project light in a C-type processor system). In the 1990s, Digital C-type print was a solution to address the limitations of the transition of analogue and digital workflows; however, the prevalent inkjet printing technology makes the digital C-type print a less popular choice among photographers. In East Asia, digital c-type printing is available in Taiwan and Japan only. This printing technique is neither widely available nor popular even though it is a good technology for photographic printing. The future of the digital C-type print is unknown and is perhaps soon to be dismissed. In a way, this printing technique offers an analogy for the political situation in Hong Kong. In 1984, Deng Xiaoping proposed a “one country two system,” policy; the famous principle to promise 50-years of prosperity (1997-2046) for Hong Kong’s transition from a British colony to a Chinese special administrative region. Like a digital C-type print, this was a solution to maintain a stable transition while taking advantage of two very different (political-economical) systems for a better future for Hong Kong. At a time when the new imposition is rapidly eliminating the “two systems,” Lin’s deliberate use of digital C-type printing today could be considered a ‘protest’ to the mainstream workflow as well as a subtle echoing of the general despair in Hong Kong when one extreme system is in the process of replacing an earlier, fragile equilibrium.

A Conclusion for Now

Two and a half decades before 2046, we Hongkongers are experiencing the end of one-country-two-(political/legal)-systems. In the course of writing in Fall 2021, not only is the public-political arena in Hong Kong constantly changing, but the visual arts and media communication scenes in Hong Kong are also experiencing a sweeping change of law and order. The shutdown of Apple Daily in June 2021, one of the most vocal and liberal newspapers in Hong Kong and in East Asia, is exceptional and also predictable in the sense that the freedom of speech in Hong Kong is close to an end. The M+ museum, for instance, pixelated digital contents on its digital and online collection because of the politically sensitive nature of a particular image to the Chinese Communist Party. The World Press Photo 2020 touring exhibition in Hong Kong at the Hong Kong Baptist University was cancelled three days before its opening, but fortunately it found a second exhibition space in a commercial venue in Hong Kong. These instances are public knowledge but they are only the tip of the iceberg.

However, when we Hongkongers are tumbling in the wheel of time, it is also a moment to witness the making of history. Making, collecting, and reading Hong Kong’s photobooks are ways to engage with Hong Kong’s current situation and connect our past, present, and the making of future. The underground and independent efforts of photobooks and photo zines in Hong Kong have flourished in the past several years, which has led to informal photobook reading clubs, pop-up photobook stores, online publishing, and many others. Both formal and informal infrastructures for photobooks in Hong Kong are waiting to bloom in the near future to create a healthier and progressive ecology of visual culture. The nimbleness and flexibility of photobooks in the ways they can be created, funded, distributed, and preserved might make them continue to grow even in an age of censorship and self-censorship, through grassroots support from individuals and institutions and through financing by crowdsourcing. Disobedient photobooks will continue the spirit of meaningfully engaging with social and political realities through photography and visual narrative, creating critical space to reflect on the geopolitical struggles of Hong Kong and China, escaping from the harsh and punishing regime through creative erasure and other tactics to survive.

LEE Wing Ki is an artist-researcher based in Hong Kong. His research interests include photographic practices in the East-Asian context, post-photographic practice and critical digital humanities. His recent research project, titled 'Disobedient Imageries: How new media, digital image technology, and algorithms redefine photographic truth in the public and virtual spheres of the 21st century?’ examines the roles and intersection of photographic imageries, civil disobedience, and technology. He is currently an Assistant Professor in photography at the Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University and a visiting researcher at the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, London South Bank University.

Notes

Antony Dapiran, City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong: Penguin Specials (Penguin Group Australia, 2017).

The author would like to clarify that civil protests have a much longer history in Hong Kong that can be traced back to British colonial governance. For instance, the pro-China student protests that took place in the 1960s and 1970s. The disobedient photobooks discussed in this article differ ideologically from the student protests of the 1960s and ‘70s.

The research of this article benefited greatly from the opportunities provided by this festival. For further information please visit http://hkphotobookfest.org.

Zheng Gu and Stephanie H. Tung, “Introduction,” in The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present, ed. Martin Parr and WassinkLundgren (New York: Aperture, 2016), 13–21. See also YinHua Chu, “The Photobook Phenomenon: From the Perspective of Taiwan Photography History,” Photographies 14, no. 1 (January 2, 2021): 85–93.

This exhibition presented more than 180 photographers’ monographs and photobooks to the public over a 6-day physical exhibition. It is worth emphasizing that this article is not a comprehensive and historical survey. One may observe that the photobooks in this article are all made by male photographers. The author will continue his efforts to explore protest image and photobook publishing by both male and female photographers. My selection is partly determined by the accessibility of available sources. For instance, this article does not touch upon photo zines, which were often found distributed as grassroots propaganda at the protest sites in Hong Kong and worldwide.

For some examples, see Weiyi Li, “Kangyi yingxiang yu Taiwan: sheyingshu de guandian,” Sheying zhisheng, no. 13 (2014): 14–23; Li-Hsin Kuo, “Politicising Documentary Photography: Ren Jian and Guan Xiao-Rong in Late 1980s Taiwan,” Javnost - The Public 14, no. 3 (January 2007): 49–64.

Along with the two photobooks, Hironori Kodama also published a zine entitled Hong Kong’s Diary – Water, an 18-page black-and-white xeroxed copy zine including images of the happening and reflection by the photographer from June to September 2019. Handmade and ephemeral publications have come into fashion in grassroots movements in Hong Kong and the rest of the world. The discussion of photo zines related to protest would require additional scholarly research to examine its importance.

For an in-depth study on the term and the complicated social relations and dynamics, see Thomas Gold et al., Social Connections in China: Institutions, Culture, and the Changing Nature of Guanxi (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

The making of the ‘Tank Man’ as an iconic image through artistic and creative appropriations experienced a revival in recent years, for instance Hong Kong-born and Denmark-based new media artist Winnie Soon’s Unerasable Images (2018-19) and the Tank-Man-Meme (2013) by an anonymous netizen. For a contextual analysis of The Tank Man image and the remembrance of the Tiananmen Massacre on social media, see Yasmin Ibrahim, “Tank Man, Media Memory and Yellow Duck Patrol: Remembering Tiananmen on Social Media,” Digital Journalism 4, no. 5 (2016): 582–96; Margaret Hillenbrand, “Remaking Tank Man, in China,” Journal of Visual Culture 16, no. 2 (2017): 127–66; Margaret Hillenbrand, Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China (Duke University Press, 2020), 168-207.

For the birth of Tank Man image as an iconic image in the contemporary American context, see also John Louis Lucaites and Robert Hariman, ‘Liberal Representation and Global Order: Tiananmen Square’ in No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture and Liberal Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 2007), 208-242.

Please see a review of the image and the work of Franklin at https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/the-making-of-icons/

Wong Kan Tai have been employing photobook as a publishing format for his personal and long-term projects. Wong has created more than 10 photobooks in his professional career. Another project related to Hong Kong and the Handover of Sovereignty is Secret 1842-1997 (2019) published by Mahjong Publishing . Unlike ‘89 Tiananmen which is considered as a visual journalistic and anthropological account, Secret 1842-1997 takes a conceptual approach to re-examine historic pictures and archival documents of Hong Kong. Whereas Beijing Story (1999) published by Hong Kong Humanities Press is a collaboration between Wong and Karl Chiu to recollect photographic works of Beijing by the duo between 1989 to 1999.

1989 We will not forget is not the first attempt of Tse’s travelogue series. Tse Ming Chong had been making pocket-size travel photo albums before his 1989 visit to Beijing, for instance he published on trips to Yunnan, China; India, and Israel. Unlike the previous three attempts, 1989 We will not forget stands firm on its own and survives to date because of its historical significance.

In China, coverage of the Tiananmen Massacre and the June Fourth Incident in 1989 is heavily censored. Even The Truth about Beijing Turmoil (1990), published in Beijing as the Chinese government’s public and official account on the June Fourth Incident, is banned. See Martin Parr and WassinkLundgren, eds., The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present (New York: Aperture, 2016), 262.

Today, Sing Tao Publishing is considered to be a pro-establishment publisher whereas City Magazine is a pro-democratic lifestyle, intellectual, and cultural magazine with a wide readership of the petite-bourgeoise in Hong Kong. I would like to clarify that the polarisation of political opinion and motivation in Hong Kong was not a pressing concern in 1989. Most mass media would support the student protest in Beijing due to humanitarian concern and care.

Clean Hong Kong Action, presented in Siu’s solo exhibition Unreasonable Behaviour (2021) at the Goethe-Institut Hongkong, received a first prize in the Photobook Dummy Award in the First Hong Kong Photobook Festival in 2021.

It is important to differentiate the “Clean Hong Kong Campaign” advocated by Hong Kong’s colonial governments in the 1960s and 1970s. The “Clean Hong Kong Campaign” in the 1960s was a public campaign for public hygiene whereas Ho’s advocacy is a propositional campaign for the censorship of freedom of speech. One may take Ho’s proposal as a parody of the namesake campaigns of the past. But the negative impacts and consequences of Ho’s proposal, albeit actualized, is not comparable to the public hygiene campaign in the 1960s.

Artist’s Statement for Clean Hong Kong Action by Siu Wai Hang. http://www.siuwaihang.net/Clean%20Hong%20Kong%20Action/cleanHK.html

Xu Yong’s Negatives enjoys international success with several publications and exhibitions, for example, the 2015 edition by New Century Press (Hong Kong), the 2017 edition by Verlag Kettler (Germany), and Negatives: Scan by Distanz (Germany) in 2019.

One example is Zhang Dali’s The Second History (2006), which resulted from an archival project and an exhibition. Zhang Dali examined national archive and news picture depositories to reveal how photographic images were manipulated in Mao’s China. The Second History received its greatest attention in the international context, but the photobook itself could not obtain official approval to be published or distributed in China.

The 2012 protests were responses to go against the proposal and implementation of a new curriculum on moral and national education in Hong Kong. Public pressure groups were formed since the 2012 protests, for example, ‘Scholarism – The Alliance Against Moral & National Education’ that is formed by a group of secondary students such as Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow.

For example, Ko Chung Ming’s project Wound of Hong Kong (2020) (https://www.worldphoto.org/sony-world-photography-awards/winners-galleries/2020/professional/winners/1st-place-wounds-hong-kong) and Australian photographer Adam Ferguson’s Masked (2019) (https://adamfergusonstudio.com/masked) for Time Magazine, February 3, 2020.

https://www.wikiart.org/en/alfredo-jaar/the-rwanda-project-the-eyes-of-gutete-emerita-1996.

Chan Kai Chun, Wound of Hong Kong, Hong Kong: Brownie Publishing, 2020

See Paul Yeung, ‘Trauma and Photography’ in Wound of Hong Kong, 7-9.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, New York, US: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

2020-1841 (2021) is a print-on-demand boxset collection in an edition of 50. It is the afterlife of the photographer’s exhibition of the same title (2020) in Hong Kong. The exhibition includes works by Lin from 2017 to depict and document Hong Kong through portraiture, still life, and landscape/cityscape.

Roberta Wue et al., eds., Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855-1910 (New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1997).

The collection includes thirty-one 11 inch x 14 inch digital C-type prints.