Photographic Rehearsal: A Still-Unfolding Narrative

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Figure 1: Lily, from the series “Delhi: Communities of Belonging,” 2016

Figure 1: Lily, from the series “Delhi: Communities of Belonging,” 2016 Introduction

How might photography illuminate the complexities of identities obscured and even erased by the legacies of empire that have shaped the very language within which we come to know and name our desires? My photographic work, often based in Delhi, India, a megacity where I was born, raised, and frequently return to, examines the visual terms in which identities blur and overlap. In this work, I consider the overlaps and contexts in which multiple identities can be claimed despite the challenges that a dominant English language culture poses for expressions of gender and sexuality.

While language has made it possible to express desire, love, and identity, it has also resulted in erasures. In the subcontinent, these erasures stem from colonial histories that made the English language “inaccessible to the mass of Indians who employed indigenous languages for both communication and the creation of literature” and “has continued to be the vehicle of divisiveness” long after independence.[1] Notably, the first Indian rebellions in 1857 marked the beginning of repressive laws, including the Anti-Sodomy Act under the Indian Penal Code’s Section 377 (1861) and the Criminal Tribes Act (1871). The latter made it compulsory for all eunuchs to register themselves and declare their property to the state and enabled bureaucrats to prosecute and even erase hijra from Indian society.[2] This group was disparaged because its gender expression did not align with Western norms. The 1871 Act went so far as to use hijra interchangeably with “eunuch” without regard for cultural nuances, discursively making them pariahs in their own home and land.[3]

The surge in the globalization of queer activism––largely shaped by Western sexual politics and by AIDS/NGO-driven categories—has further overshadowed indigenous gender identities.[4] I saw this first-hand during the 1990s when I began working in Delhi as an activist in the “AIDS service industry,” attempting to democratize access to information and health services through HIV projects.[5]

Figure 2: DART community centre in Delhi, which is no longer active. From the artist’s archive, circa 2000.(She was showing her palms covered with his name, above which a heart with an arrow was cutting across, to a friend. She was amused, but also content.)

Figure 2: DART community centre in Delhi, which is no longer active. From the artist’s archive, circa 2000.(She was showing her palms covered with his name, above which a heart with an arrow was cutting across, to a friend. She was amused, but also content.) For example, the introduction of the term MSM (men who have sex with men) dehumanized the very community it was meant to help because it simplified complex ways of belonging and loving, rendering other gender identities inferior and homogenizing expressions of desire.[6] This form of activism also problematically abridges the term kothi. As a self-selected identity that mainly documented a subculture, kothi referred to underprivileged men, who often acquire feminized mannerisms, hairdos, and names. These men occasionally altered their clothes to exaggerate effeminacy. Though they were sometimes married to women, they frequently sought masculine sexual partners.[7] And yet, the lexicon imposed by HIV/AIDS discourse resignified kothi so that it epitomized AIDS vulnerability, a status of victimhood that holds to this day.

Notably, in NGO settings, accounts of violence and victimization are often narrated by the “subject” population themselves in order to access support and services. That is, the only way to validate their status as project beneficiaries is to produce such accounts. When others speak on their behalf, hijra and kothi are perpetually spoken of as an alternative to mainstream sexuality and gender discourse. Many representations of kothi and hijra or anyone who desires to transcend the gender assigned at birth, reductively start with phrases such as “a woman trapped in a man’s body,” suggesting links to Freudian scholarship, which pathologizes gender and sexuality.[8] This approach not only trivializes queer desires but also devalues the fight for dignity by narrowly portraying hijra and kothi as unhappy in their body. It also overlooks the long history of repressive laws inflicted on them, from colonial times to the current Transgender Persons Bill, which not only threatens their freedom to choose their gender, but also creates bureaucratic processes that are hard to penetrate.[9] In the absence of a diverse conversation on trans issues, dominant perspectives can also foster an image, however unintentionally, of ideal men and women. The hijra presence destabilizes the normative structure of gender discourse.

In 2009, the Delhi High Court declared Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code unconstitutional. In its decision, the High Court argued that these archaic laws disrupt the constitutional tenets of equality and fundamental rights of LGBT people. Keeping Section 377 in the statuary books contradicts the overarching provision of constitutional rights to Indian citizens. At its core, it was an encroachment on the right to life and liberty. Ensuing conversations around gender and sexuality are democratizing, prompting healthy debates among queer activists.

However, the language in which these legal debates unfold remains exclusionary. This is demonstrated further with the sudden inclusion of “privacy” between consenting adults at the core of the language used in the first judgement on Section 377 in 2009. The privileges gained through this judgment are primarily accessed by the middle and upper classes. These rights were not fully extended to minoritized communities in India. Moreover, these developments expose as well as confirm the persisting biases and inequalities of the rule of law.

This complex context suggests the problem of translation for expressions of gender and desire among kothi and hijra communities in India, which I take up in my work. Featured here are selections from three photographic projects in which I attempt to engage with the challenges of translation. These three projects include Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others (2014), Not at Home (2014), and more recently, Delhi: Communities of Belonging (2016), a collaboration with the South Asian artist, Sunil Gupta. The hijra are formally referred to as kinnar in northern India and aravani in southern India.[10] They are divided into many subgroups, including jogappa, jogta, ali, and more. These subgroups have their own cultural practices, origin stories, and mythological connections—a diversity that cannot be grasped within the reductive framework of assumptions about sexual and gender identities that until recently has dominated the scholarship of sex. Though they live on the margins of society, hijra are understood to be empowered by their unique relationship with their guru and have been accepted in many South Asian societies. Some members of this community can maintain their role as toli-badhai, performing at weddings and at (male) childbirths.[11] In the absence of structural change to redress inequities, however, many hijra are compelled to beg and take on sex-work to survive. Only an exceptional few have attained prominent positions. Such conditions underscore the hjira’s ongoing social marginalization, which is marked by class-based geographies.

By photographing the hjira in Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others (2014), and Delhi: Communities of Belonging (2016), I sought to contest the disparaging popular image of this group, and to restore hope and extend dignity to my sitters. My objective was to consider the conditions that deprive hijra of access to self-representation, to reflect on the danger of speaking for the subjugated, and to consider the impact of doing so on this community. At the same time, I am mindful of the structural and prevailing power imbalance between the photographer and photograph/ed. Yet my own positioning on the other side of the camera makes me aware of the ethical boundaries and vulnerabilities, as well as anxieties, of “being-seen.” Although at times this awareness is burdensome, it informs my visual practice. To address the fraught terms of this awareness, I have also turned the camera lens on myself, as shown in selections from Not at Home (2014), to explore delicate relationships with home, family, lovers, and to confront notions of masculinity and patriarchy.

Figure 3: Untitled 1, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014

Figure 3: Untitled 1, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014 Figure 4: Untitled 24, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014

Figure 4: Untitled 24, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014Encounter with photography

When it comes to making images and using language, Jacques Rancière directs us to a more ethical way when he observes that, “Words describe what the eye might see or express what it will never see; they deliberately clarify or obscure an idea. [...] There is visibility that does not amount to an image; there are images which consist wholly in words.”[12]

I began these projects by making a series of studio portraits in the early years of my formal encounter with photography. Since its inception in the late nineteenth century, photography was deployed to document and to impress the Indian elite class; it has gone on to become a widespread visual form in India.[13] Notably, colonial photographers used the camara to study their subjects through formal portraiture, a practice informed by as much as it perpetuated the uneven power relationship between operator and sitters. In addition, photographers documented the landscape as evidence of the imperial power’s holdings and found similar patronage amongst the native ruling class who mimicked their colonial overseers. Given the imposition of the imperial eye in the history of Indian photography, my own photographic practice has sought to queer Indian portraiture. Through this means, I strove to maintain a faithful commitment to the sitter’s lived experience and to establish a sense of poignancy while avoiding the temptation to glamorize.

In Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others, I invited friends to a makeshift studio at a community center in Delhi to take control of the camera’s gaze. I asked sitters to strike a pose they were comfortable with and which would reveal something intimate about them. They often ended up borrowing poses from Bollywood and popular TV shows. Many sitters came in pairs and some even invited me into their frame. However, in the final edit, I opted for everyone to have their own canvas, where they were free to paint their own picture the way they wanted. Once sitters were familiar with the space between them and the lens, I wanted them to have a human encounter with the camera and consequently with viewers. Eventually, they began to express humility and closeness.[14] Because sitters would sometimes feel intimidated by lights, props, and cameras, I decided to keep the compositions minimal.

I made the red backdrop by repurposing an old carpet found at the community center. Red is an important color in many sub-cultures in India, connoting not only sensuality, love, and faith but also danger. The red dot on the forehead and sindoor on the parting of a woman’s hair marks their marital status, which is also a significant form of affiliation for some of my sitters. Red signals the “red-light” areas, surrounded by brothels, where sex-workers live and ply their trade and the location of one of the community centers I used to work at. Red symbolizes the red-light at traffic stops, where a segment of the hijra population would start their work of begging and blessings from vehicles at these intersections. Red is a reminder of the red ribbon for AIDS awareness, which is why we came together in the first place. Just as importantly, red represents blood, which not only carried the virus but also denotes kith and kin, blood relationships privileged in a caste society—while serving as the basis of hate, war, and violence. And yet we all share the same blood. Even though my sitters came from different communities, castes, and religions, the red backdrop ties everyone together,

Just as importantly, the title of this project, Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others, brings into focus my problem with translation. After all, MSM, the official term adopted by HIV/AIDS NGOs, is insufficient for this diverse community. I wanted to use an inclusive language, which recognized and honored my sitters’ preferred gendered and sexual identities. My work endeavors to respect the decision to reject globally accepted terms, which erased the specificities of their desires and experiences. The portraits reject the victimization produced through the lens of NGO activism by representing the playfulness of the sitters’ eyes, the sensuality of their poses, and the celebration of their femininity, which highlights an unspoken femme-politics.

In this portfolio, I share some of the collaborative stories that unfold as part of the process of creating these three projects. Rather than simply display a set of images from the series, I present this work in the blended form of a conversation to emphasize the dialogic nature of the collaboration which between me and my subjects. Conceived as a conversation, these stories weave the unruly liveliness of spoken language and evolving impressions with the richly textured visual forms of expression. Through this blended form, I sought to engage and explore ways of refusing the constraints of translation.

Figure 5: Untitled 2, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014

Figure 5: Untitled 2, from the series “Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others,” 2014Photographic Rehearsal

The Story of Her

(Unknown Date of Birth – 17th July 2004)[15]

The more I observed her closely, the more I realized that she did not need theory to exist, to belong, to perform desire, or to use the erotic to express, nor did she need to make any excuse to undo, her gender. At the same time, whenever she felt like it, she kept evolving and manipulating gender. She did not rely on anyone’s narratives to make her presence. People like her are innate to and coexist in our societies and cultures. Perhaps, no language can describe these complexities within her nature. But now that she is no longer with us, I dare to put a fraction of her life into words, even if they fall short.

I witnessed her charm when she walked those entangled narrow lanes of the Trans-Yamuna River; it was alluring.[16] She used to tell me that in the 1980s, like any young person full of surety, she too felt that the world was beneath her. She owned the neighborhood where she lived, longed, loved, and lusted over boys. These busy, bustling, and brazen streets do not allow for languor and she felt herself come alive when she entered. However, she would insist on meandering slowly in the early hours of the evening, after the boredom of long afternoons. I think she walked slowly because she wanted to be seen. I, on the contrary, wanted to be invisible, and always rushed, eager to go back to her place.

She disliked the shortness of the period of miniature dusk when day meets night. She often said, “if this weather were a man, he would be that sulking lover who in his immense covetousness ends up losing his chance altogether. However, then, now, he wants to reprimand others, that is why we never get long dusks here so that we could not meet our lovers. That is his revenge.” After reaching home, she would languish about, like Pakeezah, the big-hearted courtesan in the famous Bollywood film.[17]

In my meetings with her at the market, I realized this twilight period was intriguing because all activity seemed intensified. The bangle shop illuminated its fairy lights, the vegetable vendor sprinkled water on his wares while offering his best bargain, and the cassette store blared loud music to entice shoppers. I noticed how effortlessly she switched genders as she meandered between the bangles, on her way to the vegetables and through the music shops, only to switch again before returning home. Her final stop used to be the cassette store, especially if they played songs such as Main Teri Hu Jaanam and Ramba Ho.[18] She particularly liked the verses of Ramba Ho, a Bollywood rendition of I Feel Love by Donna Summer.[19] While we stood on the street, she tried to lip-sync. I could almost feel the music coming out of her body, swaying so close to the loudspeakers, sweeping away the dullness of the day, and turning everything afresh. It was pre-FM radio days, so not all the latest songs played on national radio. We requested the radio station to play our songs in the Aap ki Farmaish, but we often waited at least a couple of months to have them aired, if at all.[20] So, I could see why she did not want to waste any opportunity to hear her favorite song and did not care if passersby gawked at her flamboyance.

No matter how often she tried, she never got the lyrics right and confessed that, “only much later did she realize that those were English lyrics in a Hindi song,” and it was a constant switch between the two languages. “No wonder the English (lyrics) were not able to fit in my mouth,” she said. We both laughed and then sighed.

At times, it was hard for me to tell the difference between her songs and her sorrows. She would always try to keep me at the edge, an ability that prompted strong emotions from people who watched her perform. Once, I asked her about this switching between genders and persona. “Don’t you know that I am an Ichchādhāri Nāgin?” she confessed, then burst into loud laughter.[21] Later she described it as “a strategy to survive to stay clear of rowdy men.” She insisted I learn this skill of gender switching because even after being so audacious about life she cautiously said to me, “for us who lack a monetary fortune, the courage to challenge norms is our only treasure.”

I believed that, somehow, I have always been part of her formulation of “us.”

This fear or mistrust of fate was the only negative remark that I heard from her. But she quickly contradicted it, saying proudly, “Main Takht Ki Bigdi Hoon, Waqt Ki Nahi” (I have been corrupted by desire, as it were, and that is not accidental, by any means). I took this to mean she never bought into victim narratives. When would I become like her, I wondered? When would I be able to say I am the way I am because I so desire and not by chance?

Would I ever be like her?

Figure 6: Lily at home, from the series “Delhi: Communities of Belonging,” 2016

Figure 6: Lily at home, from the series “Delhi: Communities of Belonging,” 2016 In the closing scene of Umrao Jaan, a tragically romantic Bollywood film set in the mid-19th century at the beginning of the first mutiny, the titular famous courtesan, returns to the home from which she escaped.[22] In the end, after her birth family rejects her, after she loses her fame, and after the failure of her love affairs, the protagonist looks into an old mirror. She removes the dust from its surface, with hope, to find a future in the ruins of her past.

I had this image in my mind when, for Delhi: Communities of Belonging, I photographed Lily in her home. She had also returned to claim her share of the parental home after being away for several years. This is also a sign of a time that has passed. This theatrically layered image is an homage to cinema, where the curtains remained open, even after the end of an act. But, unlike Umrao in the film, Lily saw her younger and idealized feminine self, where she is dressed in similar Bollywood fashion (figure 7). In this photograph, Lily looks through what appears to be a window, except this does not provide her access to the outside. Instead, the gesture marks a veneration of her altered-Bollywood self, internal and self-reflective. As a photographer, looking upon her self-regard as a photographer, it seemed to me the gesture was also a refusal to be seen. Her back faces us, an affront to our gaze.

Interlude: A Room at the Periphery

In March, 2001 at a drop-in center located in an urban slum of northeast of Delhi, a roomful of people start their weekly meeting, focusing on the day’s topic, “Main Kaun Hoon?” (Who Am I?).[23]

One of the volunteers explained the theme to the group and encouraged people to feel free to express how they see themselves. To break the ice, the volunteer introduced himself.

“Hello everyone, I welcome all of you to today’s meeting. I consider myself an MSM. For those who haven’t heard this term before, MSM stands for ‘Men who have Sex with Men.’ It has been used by NGOs such as ours, to describe people like us; our community.[24] I have been working with the ‘Saksham’ for the past seven months and I am proud to be part of our MSM community.”[25]

Before he has finished, Ananas Wali Mausi, a 53-year-old person, interrupts with a question. “Will I be part of the SNM?”[26]

“Err, MSM not SNM.

– a man (the volunteer pointed at himself, putting his right hand on his heart)

– who have (pointing his finger in the air, as if he is evoking something)

– sex with others (bringing both hands together and forming a lock shape)

– man” (gesturing at everyone)

– a man – who have – sex with other – man.

“Ahh... however, I am not a man,” Ananas Wali replied to a burst of laughter.

“Sure,” the volunteer said, “but MSM is an umbrella term that covers all biologically male (assigned at birth) sexual identities including transgender (woman), transvestite, kothi, and hijra.”

“Oh, I see,” Ananas Wali reflected. “Is that what people are called in bahar-desh (abroad) these days?”

(No one knew this person’s real name, hence the name, Ananas ‘Wali’, a female pronoun, for someone who in this case selling ananas [pineapples], and because she was older, so people would call her Mausi [aunt] out of respect. It was common to use female pronouns to address each other without essentializing cross-dressing, for it makes it easy to switch between genders. In her case, one of the reasons for not wearing female clothing was that she had to work in public spaces. In those days, one would attract humiliation and violence especially if a male-presenting person cross-dressed while doing a man’s job; sadly, still true.)

She asked again, “So, will I be an MSM outside the center?”

Another participant chimed in, “And if yes, and how will my friend know that I am an MSM; they don’t come here?”

The volunteer raised his fist, a symbol of unity, and explained, “This language is designed to make work easier within the NGO sector. To work with the international communities, we all are together in this fight against HIV.”

Figure 7: Interiors, Delhi. From the artist’s archive, 2018

Figure 7: Interiors, Delhi. From the artist’s archive, 2018Becoming, Camera

During one of my trips in Delhi, I received a call one morning. “Haye! Tum To Bade Bemuravvat Ho Gaye Ho, Abto Tum Ghar Aate Hi Nahi” (You have become very unkind towards me, you don’t even come home anymore. Sigh!). Her voice deliciously husky, she said, “Come meet me this Friday.” I agreed without protest and found out when I arrived at her house that she had also invited other friends over for a party. I asked her what are we celebrating?

She said, “I saw a film in which big families get together for almost everything, constantly: they sing and dance at festivals, weddings and so on. Since not all of us live with our families, I thought we must exult whenever we can.” So, we did.

While having tea, I observed the laughter, teasing, and cooking in this small but energized room.[27] Then I noticed their handbags hanging on a nail, and the rope across the room with her clothes that were left to dry – all forming a strange sculpture in time and space, silent witnesses of the evening. To preserve this moment, I took a couple of mobile phone photographs of the handbags (Figure 8). She chuckled and asked, “What purpose will it serve? Normally people come to photograph me and my friend. But no one takes a picture of our belongings. What story can our handbags tell?” I wondered what could she know about Art and Photography? Still, I could not find a suitable answer for her—or myself—as to why I took a picture of those dangling handbags – “Just like that.” I replied.

“Take the picture of either us, here or go outside but not our stuff,” she emphasized. Stepping back from that moment, I saw there was more to her question. Perhaps, it was prompted by her past experiences with photography or by her reflections on the film she watched the other day. Documentary photography is conventionally invasive.

It is possible that she may have learned that photographic practices tend to capture the supposedly scenic by lingering on troubled faces, or by featuring surroundings as a means of fixing location. It thereby encourages the formations of assumptions about the origins, cultural backgrounds, and social aspirations of the people who appear in the photographs –– as if they have no voice, which frequently distorts the systematic and endemic suppression of the poor.

I told her that this cathartic performance has become our destiny. She replied, “It doesn’t bother me if they want to take picture. Agar Dekhegi Nahin Toh Bikehi Kaise?” (If it does not show it will not sell). She understands the aesthetics of pain and pathos; visibility costs. Susan Sontag noted the function of such photographs in painfully striking terms, as, “A call for peace. A cry for revenge. Or simply the bemused awareness, continually restocked by photographic information, that terrible things happen.”[28] My friend knew that people like her—who have often been photographed but have limited or no access to the lives of people who come with a camera and a promise of friendship and solidarity—can only be visited in person or through these spectacularized and cathartic accounts. This realization wears me out.

Figure 8: Interiors, Delhi. From the artist’s archive, 2018

Figure 8: Interiors, Delhi. From the artist’s archive, 2018One of the ultimate goals of practicing photography, I was taught, is to be able to “go out to take pictures!” This is especially relevant in a country like India where art photography has emerged from documentary and journalism practices with deep-rooted ties to colonial photographic documentation of the empire and its subjects.[29] The knowledge and aesthetic norms of revelation that colonial photographs produce still dominate contemporary image-making practices. The language associated with the act of photography often reflects these tensions of power, which enjoins operators to load, expose, shoot, capture, and grab. This language suggests that the compulsion to seize/enslave the subject is intrinsic to photography. In short, this visible economy is rooted in a colonial language. To critique this power requires a reinvention of photography altogether.[30]

After years of creating portrait work myself as a way of addressing the issue of photographic visibility, I thus realized the limitations of portraiture. Namely, portraiture can all too easily be reduced to a representational shorthand. I have increasingly turned away from portraiture precisely because I wished to situate myself differently in the politics of representation and subjugation. What is gained with visibility? What are its costs? And who pays this cost? In other words, and importantly, whom does visibility benefit? Instead of having an exempting power over the subject to represent, my photographic projects sought to take up these crucial questions, grappling with how to take responsibility towards subjects, a task that demands accountability and ethical engagement and that requires listening, reflecting, and learning. Ultimately, I turn away from portraiture as a means of questioning modes of representation and to restore dignity to subjects.

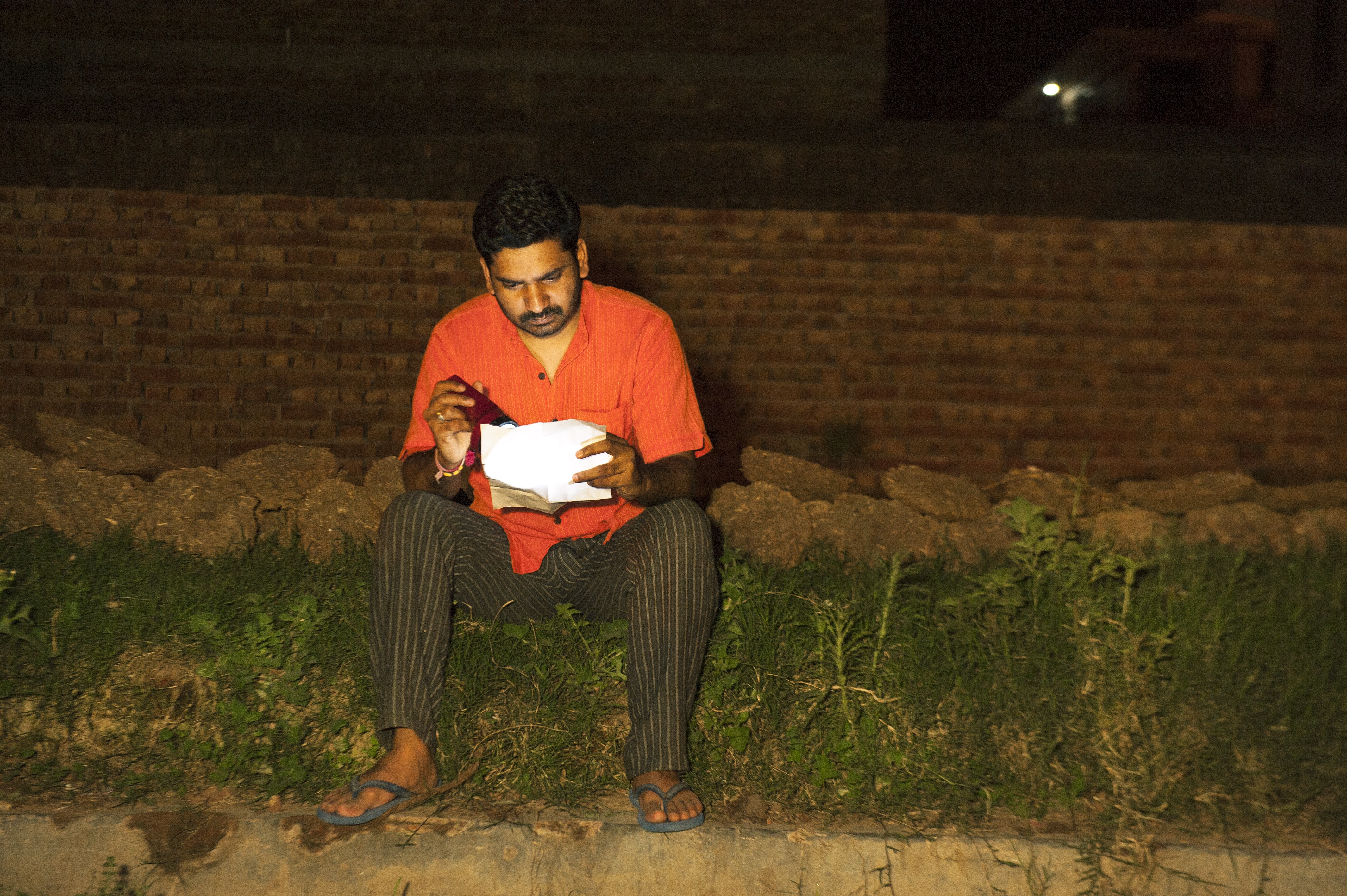

Figure 9: Untitled, from the series “Not at Home,” 2014 (In this important verdict on the section 377, private space become an important hinge, but we can only avail our fundamental rights if we have access to it. My image was aimed to portray this dichotomy between lived realities of queer people, and the language of law and human right. We did not have privacy to read our letters, let alone to express our intimate love.)

Figure 9: Untitled, from the series “Not at Home,” 2014 (In this important verdict on the section 377, private space become an important hinge, but we can only avail our fundamental rights if we have access to it. My image was aimed to portray this dichotomy between lived realities of queer people, and the language of law and human right. We did not have privacy to read our letters, let alone to express our intimate love.)Conclusion: The Limits of Translation and Visual Representation

Figure 10: From the series “Garden of Eros,” Delhi. 2016(a space away from home and the NGO; to pause, to think, to meet. Where I don’t have to be an either/or category, where their rules don’t apply, where I have liberty to create my own role, my own identity, my own life. What if, it is a life lived intermittently; it is a life nonetheless)

Figure 10: From the series “Garden of Eros,” Delhi. 2016(a space away from home and the NGO; to pause, to think, to meet. Where I don’t have to be an either/or category, where their rules don’t apply, where I have liberty to create my own role, my own identity, my own life. What if, it is a life lived intermittently; it is a life nonetheless)“From being shunned in society to being called hijras, these gay icons have faced it all to come out eventually (not from a revolving door, but) for themselves.”[31] Normally expressed by gay men this statement appears to be a complaint as it misgenders them, however, such outbursts crudely presuppose and reproduce the derogatory terms in which hijra are perceived. Yet, gay men have been seeking recognition and rights under the LGBT banner, regardless of its inherent inequalities. Moreover, much of the recent scholarship that seeks to contextualize gender and sexuality, especially in the visual media forms of photography, film, and video, was built around leading figures who are male and but who appear hyper-feminized and who temporarily adopt this identity for several reasons. But sometimes the figure of a hijra has been used to portray the “thirdness” of gender. Every so often these characters are introduced as cameos, to sing and dance or to ridicule but sometimes they can even be seen as merciless villains.[32]

The term “queer” seems to be able to absorb many forms of political discussions. Indeed, critics seeking to queer representation often distinguish between the homoerotic and the homo-social (following the theoretical terrain paved by Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick’s book, Between Men & Epistemology of the Closet[33]). This distinction establishes a dominant framework for queerness that adapts our eyes for a liberal gaze. This framework has meant that Indian societies have often been theorized as homosocial societies and have praised homosociality through art and literature. At the same time, this framework creates an ambiguous environment, which only extends a certain kind of opacity to the elite classes to avoid confrontations about their sexual identities, if they wished.

My photographic projects show, however, that the precarity experienced by hijra and kothi communities denies them the currency to purchase privacy and opacity. Instead, their lives are easily available to state scrutiny. Still, the premature celebration of the term queer suffers failure, as it is unable to translate all the cultural specificities of a gender identity, such as kothi and hijra. This failure marks my reluctance to submit to yet another cultural project of the West, one that cannot be utilized without accessing the English language, thereby succumbing to anglicized cultural imperialism. The arrival of queer discourse began as a counterculture with the promise of the anti-identarian potential of “queerness.”

Rather than destabilizing identities, queer in the context of India tends to produce fixity, due largely to its expansion within limited sociolinguistic geographies. Moreover, the world has been witnessing a naked proximity between queerness and capitalism, a shifting realm of neoliberalism, resulting in an unassailable, acceptable queer identity—an identity that the original non-conformist queers opposed. Accordingly, my objective in these projects is to offer a polymorphic, polygonal approach to translate gender photographically. At a time when everything is so sure, and so certain, where is the place for ambiguity, absurdity, and arbitrariness that comes with our desires and with our bodies that are unruly? How can one voice such concern? How is this surety helping us evolve, to possess messy reasoning and obscene love, and an absolute queer desire?

Giving accounts of feeling differently has always been a painful challenge for queer people; our bodies at times betray gender, though in deceptive ways. The recent Western vocabulary of trans might be inadequate, for it works in one location but perhaps may not work in others, which is why here, I dwell instead on the significance of translation as a way of thinking through the importance of indigenous expressions of gender identity and sexual desire in India. My own location in Delhi, and connections to and relationships with hijra and kothi, an amalgamation of subcultures, taught me that gender has its own rules, denoting “third-sex” or “third-gender”—terms that some official documents have adopted. While I resist romanticizing “third-sex” or “third-gender,” I appreciate its potential potency. Queer linguist Kira Hall writes that, “the hijras [...] have a privileged position with respect to the linguistic gender system, their experiences on either side of the gender divide allowing for strategies of expression unavailable to the mono-sexed individual.”[34] Many Indian languages have three genders and multiples pronouns that are used to address a range of relationships and degrees of intimacy.

Still, translation, which enables many of us to make sense of the world, continues to pose constraints, especially when doing so reductively describes communities that have a vast and rich history and perform their gender through language which they manipulate and reproduce as they please. To impose a global norm is to perpetuate colonial practices, which impose unsuitable categories on people who end up caught in the net of language. Worse yet, to impose global terms so deeply imbued with Western assumptions is to elide other ways of desiring and identifying, and as such, are part of an ongoing legacy of colonialism. In my discussion of my evolving photographic practice, I thus sought to present a series of conversations through an evolving photographic practice. These projects do not suggest a closure, but instead imply incompleteness and a point of departure. They are deliberately open, in the same way as the language of our sexualities and gender expressions are continuously evolving.

Charan Singh’s research and practice are informed by his involvement with HIV/AIDS work and community activism, that uses the mediums of photography, video and text to explore his 'pre-English language' life to creates artistic resistance through storytelling and fictional fragments to express multi-layered gender experiences and the ephemeral nature of queer desire. His work reclaims subaltern queer identities, sub-cultures that has been defined mainly as victims. While refusing to form of subjugation it investigates the institutionalised modes of knowledge productions that are stained with colonial past and are being overshadows by neo-colonial narratives in India. Singh is presented by SepiaEye, New York.

Notes

Anita Desai, Introduction to Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie. (London: David Campbell Publishers Ltd, 1995).

Section 377, currently amended, was known as Indian Penal Code’s (IPC) Section 377. It was originally drafted by Lord Macaulay in 1835, reworked and posthumously instigated as law in 1861 both in India and in Britain, which was then earnestly adopted by postcolonial India, suggesting the persistence of colonial ways of thinking in many British ex-colonies.

Hijra were implicated by this statute as a unique community of people. There were hundreds of other tribes that were part of this elaborated list, some tribes were even called ‘habitual criminal’. The short-term aims of the law included the cultural elimination of Hijra persons through the erasure of their public presence. The explicit long-term ambition was ‘limiting and thus finally extinguishing the number of Eunuchs.’ A detailed discussion can be found in the latest monograph by Jessica Hinchey, Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India, The Hijra, c1850 – 1900 (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Sexual politics, by this I mean, primarily, lesbian and gay politics, something I was not aware of at the time.

Though in the mid-1990s my understanding of ‘activist’ was limited to slogan shouting and public protest, in retrospect it strikes me that I always was an activist. The HIV projects I worked, was situated in Delhi, consisted of activities that included literacy, skill building, the provision of psychosocial support, and participation in health and behavioural research project. Later, as consultant, I run training and capacity building of NGO staff, monitoring and evaluation of state-run AIDS projects across India. I became critical about my NGO work and began reading. In her work, Cindy Patton poses critical and ethical questions concerning what she describes as the “AIDS service industry.”

The key population was divided into high-risk groups (HRG) for which all the AIDS funding was channelled through: MSM (men who have sex with other men), FSW (Female Sex Worker), IDU (Intravenous Drug User). Young & Mayer make a crucial point here, they write “MSM often implicitly refers to people of color, poor people, or racially and ethnically diverse groups outside the perceived mainstream gay and lesbian communities.” Rebecca M. Young and Ilan H. Meyer, “The Trouble With ‘MSM’ and ‘WSW’: Erasure of the Sexual-Minority Person in Public Health Discourse.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (2005): 1144-1149.

London-based Shivananda Khan, while extending his AIDS work in South Asia, developed what he termed the “Kothi-Concept” based on his field research, later he backed this concept through a group of organisations. For a comprehensive study of how the kothi and HIV work come about in India, see Cohen’s poignant essay, “The Kothi Wars: AIDS Cosmopolitanism and the Morality of Classification,” in Sex in Development: Science, Sexuality, and Morality in Global Perspective, edited by Vicanne Adams and Stacy Leigh Pigg (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

Similar to many other parts of the world, this phrase has been used in many ways in India since the beginning of the 1990s to describe homosexual, gay, transgender, MSM, and transsexual persons. Even after sex-change surgery, people have been described as such. Surabhi Rastagi, “Growing Up as a Girl Trapped Inside a Boy’s Body Was Not Easy: Gazal Dhaliwal,” https://www.shethepeople.tv/news/gazal-dhaliwal-transwoman-screenplay-writer/ , accessed March 16, 2021.

For an overview on ongoing debates on a transgender persons’ rights bill which is supposed to ensure constitutional protection as full citizens, see Tripti Tandon and Aarushi Mahajan, “Reclaiming Rights: Transgender Persons Bill and beyond,” https://www.theleaflet.in/reclaiming-rights-transgender-persons-bill-and-beyond/# , accessed March 16, 2021.

A detailed conversation on the series Kothis, Hijras, Giriyas and Others (2014) can be read in “Faces of Subversion: Queer Looks of India”, in Styling South Asian Youth Cultures, edited by Lipi Begum, Rohit K Dasgupta and Raina Lewis (London: IB Tauris, 2018), and in “Capturing an Indian LGBT as it should be seen” https://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/31216/1/charan-singh-capturing-an-indian-lgbtq-community-as-it-should-be-seen. Another project is Delhi: Communities of Belonging. New York: The New Press, 2016. It is a collaborative project between Sunil Gupta and Charan Singh, through 17 queer and entangled stories present a multi-layered queer archive of the city. Later this project evolved into “Dissent and Desire” and was exhibited at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston, Texas, USA (2018) https://camh.org/event/dissent-and-desire/ and subsequently presented at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Kochi, India (2018) http://www.kochimuzirisbiennale.org. All links were accessed March 16, 2021.

“Toli-Badhai” is a congratulatory blessing in return for gifts. Because it is generally performed by a group of Hijras, it is called toli (literally, “group”). Through a complex structure one gains membership within such communities that have very strict rules and hierarchies to follow in a guru-disciple relationship. In return one obtains social security and respect in society.

Jacques Rancière, (2009), The Future of the Image, translated by Gregory Elliott, (New York: Verso, 2009), p7.

There are many photographers from Europe and America who have documented this, but the example I am thinking of is Lala Deen Dayal, an Indian photographer, who began his influential photographic career in the mid-1870s.

Sometimes portraiture series such as mine can be daunting and may spark a sense of intimidation or even aggression in the viewer, especially when they are presented in life-sized prints.

An excerpt from an ongoing piece “To the Friend Whose Life Could Not Be Saved” written in the form of an obituary in the memory friend who died with medical complications caused by HIV.

The river Yamuna is one of the most important tributaries to the Ganges, it cuts across the capital city Delhi. Trans here is used to refer regions that are across Yamuna. In Hindi it would be Yamuna-Paar. The area east of the river is called Trans-Yamuna.

Pakeezah, Directed by Kamal Amrohi, 1972. “Pakeezah” means pure heart. The film is based on the life of a courtesan with unattainable desires.

She liked Bollywood songs such as Ramba Ho. Armaan (1981) Dir. Anand Sagar, and Main Teri Hu Janam, Khoon Bhari Mang (1988), Dir. Rakesh Roshan. Music for latter song was inspired from the central theme of Chariots of Fire (1981), which was composed by Vangelis.

Donna Summer is controversial because she made anti-gay AIDS statements, which enraged members of the gay community, some of whom protested by destroying her albums. However, her musical legacy remains undeniable.

An hourly request program: the literal translation is “your requests/bespeak.”

A virtuous and shapeshifting serpent, who can swiftly turn into a human. A fictional character played by many actresses but Reena Roy and later Sridevi remained indomitable. Here she refers to Sridevi, who became famous for her countless camp performances. Her sudden death in 2018 triggered many fond memories among queer people in India and abroad.

Umrao Jaan (Dir. Muzaffar Ali, 1981) is based on a novel Umrao Jaan Ada by Mirza Hadi Ruswa.

Drop-in-Centre (DIC) also known as a community centre, a common space offered supplies of condoms and referrals to clinics or to just meet others informally.

Community was used as a suffix with MSM. It soon became the expression “MSM community” but this community, unlike other communities, was only applicable during the working hours of the NGO office space.

English word for ‘Saksham’ is competence, this group name suggests making everyone competent and self-reliant.

Although there is one particular incident that would contest what has been just said. In November 2005, Debendra Kishore Panda, an Inspector General of Police in Lucknow, India, was found guilty of breaching the police dress and service rules by appearing in public and at work dressed as ‘Radha’ (the consort of Lord Krishna), stunning government officials and the High Court. Later, he was seen on various television shows and became popular as Dusari Radha (the second Radha). He now has a YouTube channel where Panda reads the Bhagavad Gita. https://www.youtube.com/c/DoosriRadhaaliasDebendraKishorePanda/feed https://www.outlookindia.com/newswire/story/up-govt-to-take-due-action-against-ig-who-dresses-like-radha/335510, accessed March 16, 2021.

Observation is crucial word choice here, even though it may not be obvious to the reader. However, this encounter took place after my formal art education and the contamination of English language in my tongue felt split, though in ways that were faint, still discernible to me. It made me aware of the split between how I thought before and the process of undoing and unbecoming I am still undergoing as I continue to read.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Books, 2004).

Mark Sealy, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time (London, United Kingdom: Lawrence & Wishart Ltd., 2019).

Sarah Lewis, “The Racial Bias Built into Photography,” The New York Times, April 25, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/25/lens/sarah-lewis-racial-bias-photography.html, accessed March 16, 2021.

This quote is from an abstract of the Gay Icons of India an anthology that claimed to tell the stories of those its author proposed as the forerunners of queer movement in India. However, the book has now been retracted in India, due to many incorrect statements. Hoshang Merchant and Akshaya K Rath, Gay Icons of India (Delhi: Pan Macmillan, 2019). https://tinyurl.com/yyulyrck , accessed March 16, 2021.

http://www.panmacmillan.co.in/bookdetails/9789386215956/Gay-Icons-of-India/3107, accessed March 16, 2021.

Cake, “How Bollywood’s Representation of Transgender People Is Downright Horrifying,” April 29, 2016. https://medium.com/the-cake/how-bollywoods-representation-of-transgender-people-is-downright-horrifying-ae396c16f2a , accessed March 16, 2021.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985) and, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

Kira Hall, "Go Suck Your Husband’s Sugarcane: Hijras and the use of sexual Insult” in Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality, eds. Anna Livia and Kira Hall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).