Reconsidering Everyday Life Photography: Saenghwalchuŭi Sajin in South Korea in the 1950s and 1960s

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

It was, indeed, a painful moment for innovating my thoughts on photography — I couldn’t take a single photo for three days after I experienced the Korean War as a war photographer. (...) Photography doesn’t exist only for expressing beauty. Photography should express every phenomenon in life. Regardless of whether it is beautiful or ugly, everything is a subject of photography. That is what I understood during the War. I named that type of photography “everyday life photography” (saenghwalchuŭi sajin) and I knew that it was the path for me.[1]

This is a quotation from the Korean photographer Im Ŭngsik, who coined the term “everyday life photography” (saenghwalchuŭi sajin, 생활주의 사진). While serving as a war photographer, Im realized the virtue of depicting objective reality, “named” this style of photography, and started to pursue saenghwalchuŭi sajin. Literally translated, saenghwal 생활 means “everyday life” in Korean. Thus the term saenghwalchuŭi sajin denotes a type of photography depicting scenes of ordinary life. Since 1955, when Im first used the term, numerous writings have taken up the concept of saenghwalchuŭi sajin. While acting not only as a photographer but also as a professor, historian and a judge for many photography contests, Im was also to play an influential role in institutionalizing the term, which has subsequently provided a basis for the dominant narrative of postwar Korean photographic history: the emergence and development of the Korean version of “documentary” photography.[2]

In this narrative, saenghwalchuŭi sajin has been regarded as a crucial starting point leading to the development of Korean documentary photography. Indeed, photographic practices that preceded the Korean War and saenghwalchuŭi sajin have also been understood as belonging to a linear history of documentary photography. In this paper I argue, however, that prior to the emergence of “everyday life photography”, photographers such as Im Sŏkche pursued a radically different type of “documentary” photography — “realism photography” (henceforth, riŏllijŭm sajin, 리얼리즘 사진) — conceived within a discursive frame that was rooted in Marxism-Leninism.[3] There was, therefore, a marked discontinuity between riŏllijŭm sajin and saenghwalchuŭi sajin, which compels us to rethink the genealogy of so-called Korean “documentary” photography.

In fact, the discontinuity between saenghwalchuŭi sajin and riŏllijŭm sajin has been noted by a number of historians such as Ch’oe Pongrim.[4] These historians have argued that the shift from riŏllijŭm sajin to saenghwalchuŭi sajin resulted from anti-communist sentiments in postwar South Korea, which drove photographers to discard the term riŏllijŭm in order to avoid being seen as sympathetic to communism. This reinterpretation has led to a reassessment of saenghwalchuŭi sajin, distanced from the explanations of Im Ŭngsik. Pak Chonghyŏn, for example, has seen saenghwalchuŭi sajin as a kind of “romantic realism” bereft of social critique.[5]

Pak and other historians recognized the difference between riŏllijŭm sajin and saenghwalchuŭi sajin. However, some have continued to use the term riŏllijŭm in a loose sense, recognizing the historicity of the Korean version of riŏllijŭm, closely related to Marxism-Leninism, but at the same time defining saenghwalchuŭi sajin as a derivative of riŏllijŭm. The result has been that riŏllijŭm has come to appear as an ahistorical genre of photography, one in which riŏllijŭm sajin of the late 1940s runs together with other genres of photography that claim to offer a transparent representation of reality. If stress is to be put on the historical grounding of riŏllijŭm sajin in order to differentiate it from saenghwalchuŭi sajin, then it is a contradiction to use the term riŏllijŭm in an ahistorical way in relation to Korean photography. This has led to problematic criticisms of saenghwalchuŭi sajin as not being “true realism” and as lacking the dimension of social critique essential to the tradition of “realism.”[6]

Taking issue with the historiography of Korean “documentary” photography, this paper seeks to differentiate the discourses of riŏllijŭm sajin in the late 1940s and saenghwalchuŭi sajin in the 1950s. My argument questions the ahistorical usage of the term “realism.” Photographic practices always take shape within specific discursive frames and histories of photography must be careful to distinguish between them. Consequently, this paper argues that the conception of saenghwalchuŭi sajin should be understood as emerging not only from fears engendered by a climate of anti-communism but also from the complex cultural and political conditions that give it a particular meaning in postwar Korean society.

Riŏllijŭm Sajin in the late 1940s

In 1948, a young Korean photographer, Im Sŏkche (1918–1994), held his first solo exhibition in the Tonghwa department store in Seoul. This was also the first exhibition of a single photographer’s work in South Korea since the nation’s independence from Japanese colonialism in 1945. Im exhibited 39 photographs depicting working-class subjects such as mineworkers and cargo workers. The exhibition has been seen by many Korean photography historians as marking a significant turn from “salon photography” (sallong sajin), a dominant style that focused on pictorial composition during the colonial era. Indeed, the exhibition marked the first time the term “realism” (riŏllijŭm) appeared in Korean discourse on photography.

Yi T’aeung, Chair of the Korean Photography Association (Chosŏn sajin tongmaeng) wrote a short introduction to Im’s exhibition in which he observed:

After August 15 [Independence Day in Korea], photographers consciously pursued a new direction with effort. They became aware of their duty to find a “genre” of photography representative of the true Korean aesthetic that would negate the vestiges of Japan. Im is one of these photographers. (...) He deviated from the delicate, sensitive and romantic atmosphere of the past, and revealed the struggles and will to live through realistic realism (riŏllijŭm).[7]

This quotation marks the first appearance of the term riŏllijŭm in South Korean discussions of photography. As such, it has been closely analyzed by historians tracing the genealogy of Korean “documentary” photography. A number of these historians have singled out the exhibition as the starting point of Korean “realism photography” (riŏllijŭm sajin) and the move away from “salon photography.” An ahistorical understanding of the term realism, however, might undermine attention to the specific characteristics of riŏllijŭm sajin. Therefore, we need to specify the defining traits of riŏllijŭm sajin more precisely and ask to what extent Im Sŏkche’s photographs exemplified a new and distinct style or mode.

Let us look, for example, at Imported Foodstuffs (1948), the best-known photograph in the exhibition (fig.1). It depicts cargo workers on the pier at Incheon — the closest pier to Seoul. Im made the photograph when working as a photo-editor for Seoul Times. At first sight, the focus seems to center on the labor of the workers. However, a closer reading shows a highly planned composition, complicating what can be taken as the intention of the photographer. The main figures in the picture are four cargo workers who are grouped in a loosely triangular composition. The right arm of the worker at the center and the right arm of the worker behind him form a diagonal line that creates a strong visual effect. Imported Foodstuffs shows its figures as static and monumental. In particular, the two workers on the truck seem artificially posed. They appear to look at each other, yet their eyes are in fact focused on some other point, making them look as if their poses were carefully scripted. As a result, the emphatically choreographed structure of the photograph undercuts the idea that riŏllijŭm sajin stood as a polar opposite of “salong photography” because of its unmediated depiction of reality. Consequently, I question then the specific historicity of riŏllijŭm sajin.

Although the term riŏllijŭm first appeared in 1948 in discourse on photography, usage of the term drew on discussions of riŏllijŭm in the literature of the 1930s. In the period of Japanese colonialism between 1925 and 1935, many leftist literary critics turned to theories associated with the Soviet Union, especially the proletarian literature movement represented in Korea by the Korea Artista Proletaria Federacio (KAPF), whose members saw the working class as the central subject of art. A 1937 essay, “Reconsideration of Realism” by Im Hwa (1908–1953), one of the most influential literary critics in mid 20th century Korea, argued that:

Realism is not related to realism, which merely crawls around the vulgar surface of everyday life...Reality should not be confused with ordinary, mundane life. People believe that realism is a narrow trivialism that merely depicts something as it is... People believe simple logic as a literary truth ... Realism should not be the surface of phenomena but an indication of their deep essence ... “socialistic realism” (soshiallijŭmjŏk riŏllijŭm) is the only realism today.[8]

This passage shows that Im Hwa clearly distinguishes the characteristics of authentic realism as going beyond the surface of everyday life. As a literary historian Son Yukyŏng has pointed out, this follows an established tradition in Marxist aesthetic theory, one that Im repeatedly emphasized in his poems and literary criticism.[9] In a 1936 essay, “The Relationship Between Literature and Action,” for example, Im cited Marx, saying, “we should remember the proposition of The German Ideology,” namely that every form of consciousness is determined by the economic base.[10] In a separate essay, “Literature and Action,” he went on to claim that labor was fundamental to the human condition, in effect producing and defining the human.[11] For Im, therefore, the essence that constituted the proper subject of realism was rooted in the experience of the laboring class, and this idea can be readily seen in his poems in which the narrators are factory workers, rail workers, and their families.[12]

Im’s formulations may not fully represent the Korean understanding of “realism”. Nevertheless, these quotations reveal the emphasis on the representation of the male worker as the embodiment of healthy proletarian virtues. Im, we should note, remained active after Independence and continued to influence literary theory in South Korea until the early 1950s. Indeed, on August 16, 1945, the day after Independence, he established the Chosŏn Literary Writer’s Construction Headquarters (Chosŏn Munhak Kŏnsŏl Ponbu), with branches in literature, art, music, and film. In 1947, however, Im fled to North Korea.

In 1948, therefore, the conception of riŏllijŭm sajin was able to draw on almost two decades of discussions by literary critics, novelists and poets. The connections between the two groups are evident in the career of Im Sŏkche himself, since he was a member of the Korean Photography Alliance (Chosŏn Sajin Tongmaeng), which was an affiliate of the Chosŏn Literary Writer’s Construction Headquarters. Im’s 1948 Tonghwa department store exhibition was even sponsored by the Alliance. In addition, the exhibition brochure prominently carried the name of the photographic studio known to be run by the treasurer of The Worker’s Party of South Korea (Namjosŏn Nodongdang). Im Sŏkche therefore must have been very familiar with Im Hwa’s theory of realism. This connection causes us to question the idea that riŏllijŭm sajin was simply a neutral and transparent depiction of reality. The Korean conception of realism is not a stylistic category but is rooted in the political analysis of leftist parties in Korea in the 1930s and 1940s.

Emphasis on the political function of photography is evident, for example, in Yi T’aeung’s essay, “The Future of Photographers,” written in 1947. Here, Yi argues:

In the past, Korean photography, without any substantial theories, were satisfied with superficially following and copying the forms of others like a robbery. Still we failed to stop doing it and, even worse, we are attempting to justify the fallacy of the past ... We should remove the poisonous vestige with relentless attacks so as to further the development of photography. It is we, South Korean photographers, whose duty it is to pursue a purifying movement and produce photographs that have the aesthetic power of popular struggles and popular expression. The hegemonic duty belongs not to the individual but to groups of revolutionaries and conscientious photographers who can propel the whole project.[13]

In the competition between leftists and the liberals, it was the Korean Photography Alliance that pushed its commitment to leftist aesthetics. The pursuit of riŏllijŭm in art and photography—and, in particular, the representation of labor already emphasized in social realist literature—has to be seen in this light. Since Im Sŏkche’s photographs depicted the working class, Yi might have seen his photographs as a model for riŏllijŭm sajin. Im’s photographs indeed did more than just picture labor in general. They celebrated victorious moments in the struggles of Korean workers, like the June 1948 victory of the Pier Workers’ Union in Pusan, just one month before the exhibition.[14]

In this context, Im’s Imported Foodstuffs can be read as a celebration of the workers’ victory, exhorting them to continue their political struggle.

Marxist aesthetic and political theories from the 1930’s continued to be influential even after Independence in 1945 and their effects can be seen both in Im Sŏkche’s photographs and in Yi T’aeung’s writings. This historical context strongly suggests, therefore, that Im’s riŏllijŭm sajin was a political intervention into the debates between leftists and liberals who were competing for power in post-Independence South Korea. Debates over riŏllijŭm sajin in Korea, however, were to undergo a radical shift with the rise of anti-communist sentiment following the cease-fire that ended the Korean War in 1953.

The Formation and Promotion of Saenghwalchuŭi Sajin

In 1948, the political landscape of South Korea had radically changed. The political repression of communism began immediately after the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was formally established by President Rhee Syngman in 1948.[15] His government formed an organization called The National Guidance Alliance (Podo yŏnmaeng) with the intention of eradicating communism. Anyone with a record of leftwing activity had to report to the organization and take prescribed training courses. Communists who refused to report had to flee and Im Sŏkche was one of these. He fled to Masan, in the south of the peninsula.

When the Korean War was started by Cold War hostilities in 1950, it further aggravated the climate of repression, and after the war, anti-communist sentiments were dominant in South Korea. Anti-communism operated as an ideology that promoted certain people and excluded others. As Ku Wangsam, a supporter of riŏllijŭm sajin, wrote, photographers who had become interested in photographic realism now had to denounce it for fear of being linked to communism. Ku was a critic and photographer active in Taegu, in the south of Korea, where he was a member of the Kyŏngbuk Province Alliance (Kyŏngbukto yŏnmaeng), a subsidiary of the leftist Korean Photography Alliance. In a 1955 essay, “On the Issue of Realism in Photography,” he analyzed contemporary Korean photographic practice, arguing that Korean photographers had begun to pursue photographic realism and move away from “salon photography,” which was “no more than a vestige of the Japanese colonial era.”[16] Towards the end of the essay, Ku lays out his idea of photographic realism: “riŏllijŭm sajin should not copy superficial reality, but should depict historical events concretely and express a vivid and hierarchical social phenomenon.” To this he adds that, “we cannot exclude social issues when we consider riŏllijŭm. Therefore, artists should pursue the production of realist photographs that have a certain social value. Riŏllijŭm is a record that concretely describes historical content.” At the same time, Ku insists, “Art is not ideology but beauty. After all, riŏllijŭm is not about an idea but about forms of art. In other words, riŏllijŭm is just an attitude that tries to see everything objectively. Riŏllijŭm is not a product of subjective consciousness.” Clearly these closing comments contradict the earlier argument of the essay, perhaps because he was worried about being seen as a communist for using the term “realism,” even though his theory of realism was not communistic at all. What we see in his essay therefore, only two years after the cessation of the Korean War, are the pressures of anti-communism that made the use of the word “realism” dangerous.

Four months after the publication of Ku’s essay, “On the Issue of Realism in Photography,” Im Ŭngsik put forward his own assessment of current Korean photography in “Photography’s Present and Future — For the Production of Everyday Life Photography,”[17] a review of a 1955 exhibition of the Association of Korean Photographers (Han’guk sajin chakka hyŏp’oe). Im mapped out the two main artistic forms in contemporary Korean photography: “There are currently two artistic trends, ‘everyday life style’ (saenghwalchuŭi) and ‘salon style’ (hoehwajuŭi), which will soon be displaced by the stronger force of ‘everyday life photography’ (saenghwalchuŭi sajin).” Im then insists that “photographers should produce saenghwalchuŭi sajin, since the artistic value of photography always lies in a truthful representation of reality.”

What is the meaning of saenghwalchuŭi sajin here? Five years later, in 1961, Im returned to his argument in “Current Tendencies of Contemporary Photography,” an essay published in Tonga ilbo, in which he declares:

Since the history of Korean photography was short and since it was impossible to not be influenced by Japanese photography, salon style photographs were prevalent until the Korean War. These were extremely limited and commercialized photographs that ignored the emotions of “the common people” (minjung) and focused only on the ideal beauty of nature. Their forms were clichéd and ossified. However, the Korean War broke out suddenly and, after the War, photographers’ subjects spontaneously shifted to social and humanistic topics. Salon pictures were swept away and the new photography has dominated ever since. This tendency has been called “everyday life photography” (saenghwalchuŭi sajin).[18]

Here, Im’s rhetorical opposition between realistic photography depicting social themes and salon pictures bears a close resemblance to Ku’s theory of realism. Why, then, did Im have to coin a new term?

We need to examine the definition of “everyday life” (saenghwal) and its implications in order to understand what was at stake. Literally translated, the term saenghwal means “everyday life” or “livelihood.” The addition of chuŭi is equivalent to the English “-ism.” Normally, the term would be combined with ilsang (the routine of life, 일상) in the phrase ilsang saenghwal (일상 생활), which means “ordinary everyday life.” The concept of saenghwalchuŭi sajin therefore alludes to the mundane scenes of quotidian life. Since “everyday life photography” (saenghwalchuŭi sajin) seems to carefully avoid any socio-political connotation, many historians of photography have argued that the term was coined in order to separate the new form of photographic realism from any connection to communism, and even politics altogether. Interviews with contemporary photographers have also suggested that the term arose from the pressures of anti-communism.[19] Some historians have even criticized “everyday life photography” as an apolitical and even depoliticized genre, in contrast to riŏllijŭm sajin, which focused on the representation of workers and historical struggles. Leading historian Ch’oe Pongrim has, for example, suggested that, “Anti-communism, which appealed to capitalists in the 1950s, must have led Im Ŭngsik to pursue a de-politicized version of riŏllijŭm sajin.”[20]

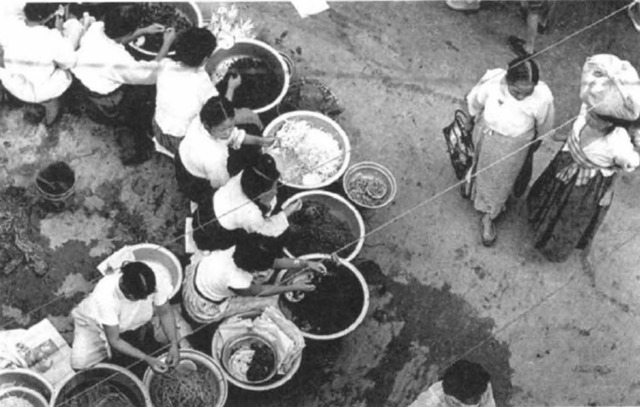

One of the characteristics of saenghwalchuŭi sajin is indeed a shift in subject matter from the working class to vulnerable women, the elderly, and children. Figures 2 and 3, for instance, show images typical of those defined as saenghwalchuŭi sajin. They seem to capture the ordinary scenes of life—a morning market where women are selling side dishes or a mother and daughter on a bench. It is clear that the subject matter of such images is different from the riŏllijŭm sajin from the 1940s. However, Im Ŭngsik and other supporters of saenghwalchuŭi sajin never specified what the proper subject of photography should be. Instead of articulating the prevalent representation of women or children in their images, the photographers only used the ambiguous phrase “depicting objective reality” and, in defining what makes a good photograph, would emphasize the “humanistic values of photography” as well as the “tones and composition of photography.” The same terms are evident in efforts to promote saenghwalchuŭi sajin, such as the activities of the New Line Group (Shinsŏnhoe), which was established in 1956, and the Tonga Photography Contest (Tonga Sajin k’ont’esŭt’ŭ ), for which supporters of saenghwalchuŭi sajin were selected as judges. Journalistic writing, including critical writing on the United States Information Agency (USIA)’s traveling exhibition The Family of Man, followed the same pattern.

The New Line Group, for example, was founded on August 8, 1956 and was active through 1960. A report from the time announced that, “The group attempts to pursue “new realism” (shin sashilchuŭi).”[21] According to Pak P’yŏngchong, Yi Hyŏngrok, the leader of The New Line Group, confirmed that members of the group sought to produce realist photographs.[22] This goal, indeed, was what differentiated the group from other photography societies and clubs. While most photography groups in the 1950s were formed to protect photographers’ rights and promote camaraderie, the New Line Group was one of the earliest groups to declare allegiance to a specific aesthetic.

From the point of view of Im Ŭngsik, the group’s photographs could be taken as exemplifying saenghwalchuŭi sajin. Reviewing a group exhibition, he hailed photographs by group members as setting saenghwalchuŭi sajin on firm ground.[23] His positive assessment was also repeated in numerous other reviews in which, for example, he argued that, “The photographs [of the group] captured the aspect of human beings living in devastating circumstances.” He went on to insist that “the images successfully expressed humanity,” concluding that “photographs lacking humanistic values are not artistic works ... they can only receive superficial criticisms.”[24] For their part, New Line Group members never raised any objection to being represented in this way as the embodiment of saenghwalchuŭi sajin. On the contrary, their influence expanded with the humanistic rhetoric of saenghwalchuŭi sajin.

Here it is worth remarking on Im’s use of terms such as “humanistic values” and “humanity.” Im clearly regarded “humanistic values” as a critical standard by which works of saenghwalchuŭi sajin should be judged. What lies behind this is the impact of a signal event in the Korean photography world of 1957. Yi Hyŏngrok, the leader of the New Line Group, later recalled that the group’s growth was spurred by the opening of The Family of Man, a travelling exhibition curated by Edward Steichen, which was held in Korea at the same time as The New Line Group’s first exhibition.[25] In this ambitious exhibition, which was first shown at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1955, Steichen brought together 503 photographs by 273 photographers from 68 countries under the unifying conception of the universality of the human condition. Im Ŭngsik has claimed that the exhibition travelled to Korea as a result of an invitation from the Association of Korean Photographers, an organization to which he belonged.[26] The exhibition was held at Seoul’s Gyeongbok Palace Museum from April 3 to 28, 1957, under the sponsorship of the USIA, the Korean Ministry of Culture and Education, and the Association of Korean Photographers.

Reactions to the exhibition can be found in numerous articles and reviews. In May 1956, for example, when plans for showing the exhibition in Korea were almost confirmed, a roundtable was held in which fifteen influential Korean photographers discussed The Family of Man. Discussants had not in fact seen the exhibition at that time, though some had at least read the exhibition catalog. Certainly they had seen enough for photographer Sŏ Sunsam to declare: “This exhibition is basically planned to send a message that all humans belong to one family and we can enjoy happiness together. And this is where the greatness of this exhibition resides.”[27] After the exhibition had opened, a second roundtable was organized on April 6, 1957. This time panelists included Im Ŭngsik, Ku Wangsam and Sŏ Sangtŏk. Im declared that:

After seeing the exhibition, I felt that it is critical for photography to give audiences energy and impression. Now there is an apparent path for photographers, and whoever ignores this path falls behind. I think this exhibition suggests the direction of Korean photography for the future.[28]

Beyond his comments at the roundtable, Im Ŭngsik also wrote a review of the exhibition for a university newspaper in which he praised the exhibition as “an epic poem of photography, the topic of which is peace and love, based on the dignity of human life.”[29]

The influence of The Family of Man also impacted the reception of other photography exhibitions in Korea. Its showing overlapped with the New Line Group’s exhibit, which dealt with the everyday life of Koreans and was seen as closely related to The Family of Man. As Yi Hyŏngrok conceded in an interview, their growth was supported by The Family of Man:

The Family of Man and the New Line Group had a lot of similarities ... Many audiences who went to the Gyeongbok palace and viewed The Family of Man also dropped by the Shinsegye department store and saw our group exhibition held in the department store. Subsequently, many of these viewers felt that young Korean photographers can also do the same thing! In other words, many audience members initially regarded the achievement of The Family of Man as the Yankee’s (Westerner’s) achievement. But after visiting our exhibition, audiences realized that Koreans could do the same thing. How could it be that the photographs were so much alike? ... I was very surprised after I saw The Family of Man, and I felt that I had done well. I decided to pursue this theme until my death.”[30]

As seen in the quotation, the impact of The Family of Man was considerable. It is important, therefore, to understand the bearing of The Family of Man on the 1950s Korean photography world. It shines light on a moment when many Korean photographers who thought of themselves as documenting reality relied on a conception of universal humanity to support their photographic practice. Later criticism has argued that the worldwide tour of The Family of Man was immersed in the cultural politics of the Cold War era. Allan Sekula has even insisted that the exhibition was a bureaucratic attempt to universalize photographic discourse, in keeping with the ideology of corporate capitalism and the promotion of American economic and political hegemony. The sequencing and captioning of the exhibition has also been seen as promoting the universality of the bourgeois nuclear family.[31] Therefore, the reactions of Korean photographers, especially saenghwalchuŭi sajin supporters, has subsequently been seen as naive. Naivete, however, was not the perception at the time.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Korean photographers strictly followed the ideas of “the representation of objective truth,” “capturing everyday life,” and the “expression of universal humanism.” The most powerful institutional focus for the promotion of these ideas and the photographic practices they supported was the Tonga Photography Contest. The contest was first launched on July 3, 1963, with the aim of raising the artistic status of photography. It came as a result of continuous requests by Yi Myŏngtong (1920–2019), photo-editor for Tonga ilbo.[32] At the time, there was not a single photography department in any Korean university. Moreover, the National Art Exhibition (Kukchŏn), a government-hosted exhibition that would be held 30 times between 1949 and 1981, had no section dedicated to photography when the Tonga Photography Contest was established. In this context, the Tonga Photography Contest had a significant effect. The following year, in 1964, photography was included in the National Art Exhibition, while a photography department was also created at Sŏrabŏl Art University. Photography started to be seen in Korea as an artistic practice and a great deal of the credit must go to the Tonga Photography Contest.

As for the first contest in 1963, the total number of entries was 521, fifteen of which were included in the color category. Similar numbers of entries continued through the 1960s.[33] Every year eight award-winning photographs were featured in Tonga ilbo and, from 1964 on, covered a two-page spread in a paper that only had eight pages. What differentiated the Tonga Photography Contest from other contests was its selection committee. Though the contest had announced that the theme for photographs would be open, Yi Myŏngtong, as committee member and Tonga ilbo’s photo-editor, pushed the view that the essence of photography is realism.[34] For the second contest, Im Ŭngsik also joined the selection committee. A 1964 article by Im shows his strong antipathy to experimental photography. He writes: “When we judged the photographs, we tried to consider the essence of photography—in other words, we didn’t admit to using montage techniques at all.”[35] As the range of award-winning photographs indicates, this “essence” was clearly taken to mean the depiction of scenes from everyday life from an explicitly humanist perspective.

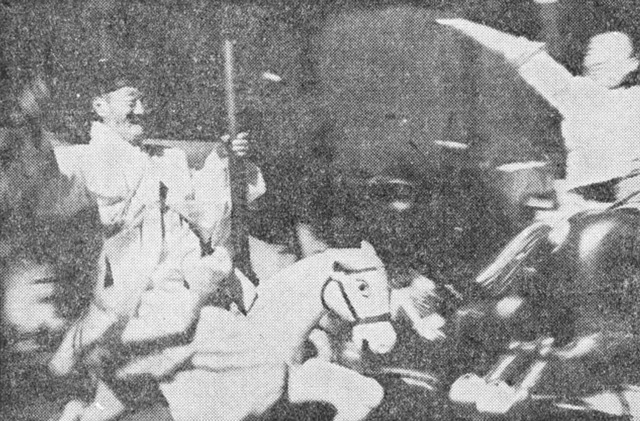

In 1963, for example, the top prize went to Shin Hyŏnkuk’s A Child’s Mind (fig. 4) in which an old man in traditional garments and a child are seen riding a merry-go-round. Ku Wangsam singled out the picture because “it shows the decisive moment of an old man and a child humorously enjoying themselves together.”[36] In response to the award, Shin Hyŏnkuk declared, “I might be living in a delight of capturing mundane objects surrounding our saenghwal through a camera.”[37] These comments by Shin and Ku, together with Shin’s award-winning photograph, exemplify the rhetoric of saenghwachuŭi sajin but also highlight the influence of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea of the “decisive moment.” Together they represented a formula followed not only by professional photographers but also by hundreds of amateur photographers who submitted works in this style every year, striving to express humanistic values. In 1965, the top prize went to a photograph of two cows fighting (fig. 5). The committee’s citation declared that “by using the distinctive mechanism of the camera, the photograph shows the emotional expression of visual images.”[38] While the photographer, Sŏ Sŏnhwa, declared, “in the fight between animals, I found beautiful ethics and fair play, which humans cannot follow.” For Sŏ, even cows could convey universal ethical values.

There is no doubt, therefore, that the Tonga Photography Contest strongly influenced the direction taken by Korean photography. As Im Ŭngsik said in 1967:

Old, painting-style photographs are made less often now. We do not see technique-centered, magical and abstract photographs any more. If this phenomenon is due to the Tonga Photography Contest, then this contest is a monumental achievement and a desirable guide.”[39]

Yet, while Im emphasized the importance of the candid and humanistic depiction of everyday life, he still demanded more of “good photographs.” “The process after taking a photograph,” he suggested, “is also important. For a photograph should have visual effects.”[40] Equally important was “refining the tone of the image.” Indeed, Im repeatedly stressed the significance of compositional effects. Reviewing the Third International Photography Salon in 1968, he commented on the “straight depiction of space” and on “charming compositions which vitalize the overall mood of the image.”[41] Saenghwalchuŭi sajin, the representation of everyday life and universal humanism did not therefore preclude formal compositions and this has led some historians of photography to criticize saenghwalchuŭi sajin’s lack of a “true understanding of the theory of realism” and its “compromising with reality.” As photography historian Pak Chusŏk wrote in 2005: “riŏllijŭm sajin during the 1950s was just 1920s’ and 1930s’ artistic salon pictures with only a little bit of transformation. Without any change in their consciousness, photographers merely changed their subject to scenes of a human life in a chaotic society. That is what realism photography was [in the 1950s].”[42]

Is it true, however, that saenghwalchuŭi sajin merely captured the surface of everyday life, giving rise to another type of artistic salon picture far from “true realism”? To answer this question, we must reconsider the meaning and connotations of saenghwal’s historical usage both in the colonial era and following Independence. This will point to a discursive intervention that surpassed the intention of saenghwalchuŭi photographers. The shift from realism to saenghwal in discourse on photography may have been due to the dangers associated with the term realism in a climate of anti-communism. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the term saenghwal was apolitical or intentionally depoliticized. What historians of photography in Korea have largely missed is that the use of the term saenghwal has a history going back to the colonial era.

Reconsidering Saenghwalchuŭi Sajin

During the colonial era from 1910 to 1945, under the Treaty of Annexation, Japan considered Korea not as a discrete country under its rule, but as a part of Japan. This tendency was the strongest in the 1930s when Japan planned to construct the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere with imperialist ambitions, which included “Japanizing” the Korean people, requiring their loyalty towards Japan. One of the strategies for Japanization was to impose physical constraints over the Korean people. The Japanese administration promoted a movement called “Campaign for Improving Everyday Life (saenghwal kaesŏn undong),” which disciplined Korean people’s bodies on a daily basis, so that they could efficiently perform their duties for the Empire of Japan and its prosperity. For example in 1936 and 1937, the campaign was designed and directed by administrative organs according to a note from the Japanese Government General of Korea.[43] In some cities, it was carried out by neighborhood meetings, social societies, and schools, but in other cities such as Inchŏn, it was carried out by the Federation of General Mobilization of the National Spirit. Under the campaign, the Korean people were, for instance, immunized heavily; kept from smoking and drinking; made to clean pathways and sewerage systems around their homes; coerced to raise the Japanese flag; and encouraged to visit and worship Japanese shrines regularly. The purpose was to discipline bodies within the central system of the Japanese Empire. Under this nationwide campaign, the notion of “everyday life” (saenghwal) was an area which had to be improved for all Koreans.

However, the campaign did not disappear after the liberation of Korea from Japan. Rather, it had been replaced and strengthened under another authority. Rather than molding submissive people for imperialistic goals, it became necessary to mold the “Korean citizen” for the purpose of nation-building. The discourse of “improving everyday life” (saenghwal kaesŏn) was produced and disseminated again under Rhee Syng-man’s government, the first republic government, founded in 1948. A newspaper article published on November 28, 1948, three months after the establishment of the government illustrates the discourse clearly:

There is a very critical assignment of nation-building—it is called ‘improving everyday life’ (saenghwal gaesŏn). Needless to say, it should be propelled in terms of both physical and mental aspects. Therefore, we established the “Improvement of Everyday Life Department” under the Ministry of Culture and Education, and have been doing research in order to develop the campaign further. Now we are in the execution phase, and it really needs the cooperation of the private sector. Therefore, we are planning to organize subsidiary committees. It is difficult to explain the details since we are currently addressing multiple issues. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that we should reach our goals under the thoroughly organized idea. The pain of everyday life (saenghwal) we have been through during the War period is beyond description, and we are still in pain. However, if we continuously make efforts to improve, it would be a huge gift for the future generations ... First, we should organize a women’s group at the state level ... By doing so we would eradicate illiteracy and enlighten people. The second thing to consider is ‘clothing in everyday life’ (ui saenghwal). Housecoats and outdoor clothes should be differentiated, and it is always recommended to wear colored clothes. The third aspect is ‘diet in everyday life’ (sik saenghwal). It is wasteful to eat more than two side dishes ... One way of improving our lifestyle is by calling for households to employ a part-time maid instead of a full-time maid residing in a house.[44]

It is important to notice that the issue of saenghwal had been raised after the establishment of the government by the liberalists in 1948. Saenghwal was a space where people had to improve themselves through physical and mental constraints. Articles related to the improvement campaign were produced between 1948 and March of 1950, right before the Korean War broke out, and after the war ended, the campaign for improving everyday life (saenghwal gaesŏn woondong) reappeared. The term saenghwal, as opposed to riŏllijŭm, was not a term used within the social realism discourse with political purposes. However, the term was highly promoted by the Japanese imperialists and the Korean liberalists after Independence. It had been used in the context of remodeling the subjectivity of Koreans by suggesting a desirable and ideal way of life. Im Ŭngsik, who coined the term saenghwalchuŭi sajin, was born in 1912 and grew up through the colonial period and the Independence era. He might have known about the implications and the nuances of the term saenghwal as much as anyone.

Considering the desire to control and discipline bodies associated with the term saenghwal, it is necessary to be cautious before regarding the term as merely a safe word in an environment of anti-communist sentiment. In turn, we should examine the term’s discursive effects, which exceed the intentions of Im Ŭngsik, the author of the saenghwalchuŭi sajin. The mistake of those who criticize saenghwalchuŭi sajin as compromising with the reality is in analyzing saenghwal only in regards to its current usage. From this perspective, the primary characteristic of saenghwalchuŭi sajin is to capture scenes from people’s everyday lives, resulting in neutral, apolitical images.. Contrastingly, focusing on the historical context of the term saenghwal, which implies conceptions of improvable spaces and ideal models of living within the disciplinary system in the colonial era and postwar South Korea, opens up another way of interpreting these images.

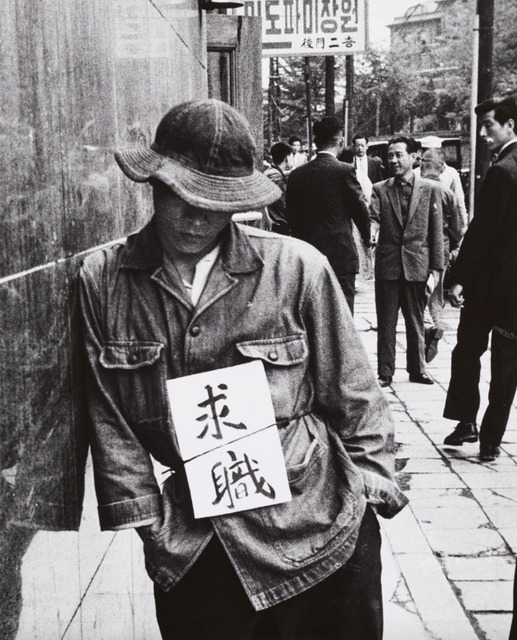

Fig. 7. Im Ŭngsik, Seeking a Job, 1953, gelatin silver print, collection of Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

Fig. 7. Im Ŭngsik, Seeking a Job, 1953, gelatin silver print, collection of Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.For example, these images unveil what the Korean people considered as “everyday life.” It is interesting that in the images of saenghwalchuŭi sajin, the role of production was mainly imposed on female subjects. Like the women working in a morning market (fig. 2), a young girl is pulling a skinny cow by its tail in a farming field (fig. 6). In many images, by contrast, the males are often represented as jobless, or as children or old men who spend their time on the streets. Im Ŭngsik’s Seeking a Job, which is often regarded as a rare example of social critique from this time, shows a lethargic male figure with his hands in his pockets (fig. 7). The above-mentioned article on “improving everyday life” also implicitly tells us that eradicating illiteracy, preparing clothes and food, and employing maids were indeed areas where females played the central role. Saenghwal was an area where females were expected to provide mental and physical labor.

To be sure, we are likely to observe different representation of femininity in the 1930s and the 1950s. A deeper examination on the representation of femininity in colonial and postwar Korea is beyond the scope of this essay, since it would require further discussions of both masculinity and femininity, considering a wide range of cultural representations. Nevertheless, I reject the view that saenghwal amounts to a de-politicized term, a perspective that criticizes images related to saenghwal based on a narrow reading of the intentions of the authors and the theories they endorsed. There are numerous ways of interpreting the images related to saenghwalchuŭi sajin. We can examine the influence of The Family of Man in relation to an ideal model of saenghwal in the atmosphere of Cold War politics. Since it was sponsored by the USIA, we can assume that it might have been promoted with the intention of disseminating “the ideal model of everyday life” in the United States in accord with a liberalist agenda. I argue that we should trace the usage of the term to discourses in post-independence South Korea. This approach enables us to deal with the political, cultural, and social conditions by which the images were influenced and in which they intervened.

Saenghwalchuŭi sajin and related images have been regarded as those that erased the representation of the working class and encouraged humanistic values through photography, promoting a naively universal conception of humanity. In some instances photographers and critics who supported saenghwalchuŭi sajin offered ambiguous criticisms in which they emphasized the formal techniques of making compositionally good photographs, while at the same time emphasizing the virtue of depicting true reality. As opposed to either mystifying saenghwalchuŭi sajin as a starting point for Korean documentary photography or flattening it as something that merely captures the vulgar surface of everyday life, we should analyze it in a different way by focusing on the complexities of its emergence within its own historical moment. Saegnhwalchuŭi style photographs were not only produced within given historical conditions, but they also intervened in historical events in a way that differs from realist photography of the 1940s.

The Space for Social Critique in Yi Myŏngtong’s “Reality” (hyŏnshil) Series

A thin, grey-haired old man is standing with a slightly hunched back (fig. 8). He is not looking at the camera, and it seems like he did not notice the photographer who captured his image. He is holding a long pipe—a rarely seen traditional Korean pipe—in his mouth. Behind him on the left, a small semicircle-shaped farmland can be seen, and further behind, there is a traditional Korean house called a ch’ogajip. Although it seems like the photograph was taken in the early twentieth century, it was actually taken in the fall of 1963.

This photograph, titled Slash-and-Burn Farmer on Mt. Chiri, was taken by Yi Myŏngtong, who proposed the establishment of the Tonga Photography Contest. The image seems to show characteristics of saenghwalchuŭi style photographs in the 1960s: an old male who shows no signs of productivity, the implication of a candid moment, and the documentation of the everyday life of ordinary people by displaying their houses and farmlands. In addition, the image shows another characteristic that distinguished saenghwalchuŭi style photographs—the documentation of scenes pertaining to suffering, poverty, and ordinary people.

In terms of its formal characteristics, Slash-and-Burn Farmer shares a lot of similarities with saenghwalchuŭi sajin, which, as described above, has been criticized as avoiding social critique. However, a close reading of the image along with an analysis of its materiality and historical conditions, reveals its function as a social critique.

The image was printed on the first page of Tonga ilbo on September 2, 1963.[45] Between August 13 to September 4, a newspaper column called “Reality” (hyŏnshil) was printed routinely (sixteen times in total), with each article accompanied by a photograph depicting everyday life in South Korea and a short explanation of the image. Yi Myŏngtong contributed seven images, including Slash-and-Burn Farmer. The caption alongside this image reads as follows:

It was about fifty years ago when the eighty-three-year-old man, Kim Pyŏngki came to this mountain. He slashed this mountain, and created a small plot of land for himself. Now he grows potatoes for a living.

As Yi Myŏngtong specified in the title Slash-and-Burn Farmer on Mt. Chiri, he did not depict an image of an ordinary old man in South Korea. The old man, who started to live in the mountains much before the first Republic government, had never voted in any election. He had also never paid his taxes. Although he lived in South Korea, he was not a citizen according to the Constitution. However, his peculiar position produces a certain effect, when placed alongside another article (fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Negotiating Presidential Candidacy in the People’s Party —A Shocking Moment, Tonga ilbo, September 2, 1963, courtesy of Tonga ilbo.

Fig. 9. Negotiating Presidential Candidacy in the People’s Party —A Shocking Moment, Tonga ilbo, September 2, 1963, courtesy of Tonga ilbo.The largest title, printed next to the image of the old man, reads “Negotiating Presidential Candidacy in the People’s Party—A Shocking Moment.”[47] The issue was published during the time the Presidential candidate registration was in process. The announcement of the election was unusual; it started when Park Chung-hee, who had seized power through a coup d’état on May 16 of 1961, abruptly announced the end of the military regime and scheduled the Presidential election to take place on October 15 of that year. While the opposition parties that did not expect the announcement of the Presidential election were left in confusion, Park quickly declared himself a candidate on August 31. September 2 was the day when the three opposition parties discussed their plans to merge and field a single candidate for the October election so as to challenge Park. The facial images in the article were the three opposition parties’ candidates, who were competing for a single position (fig. 9). Ironically, the three people who were competing in order to represent the Korean citizens did not represent the old man printed on a larger scale right next to their faces. In its literal sense, the competition among the three candidates was to argue: “I am the one who can truly represent the Korean people.” However, the image of the old man produced a radical commentary on the conception of competition, suggesting that the true representation of people by a political candidate is difficult, or perhaps even a fictional prospect altogether.

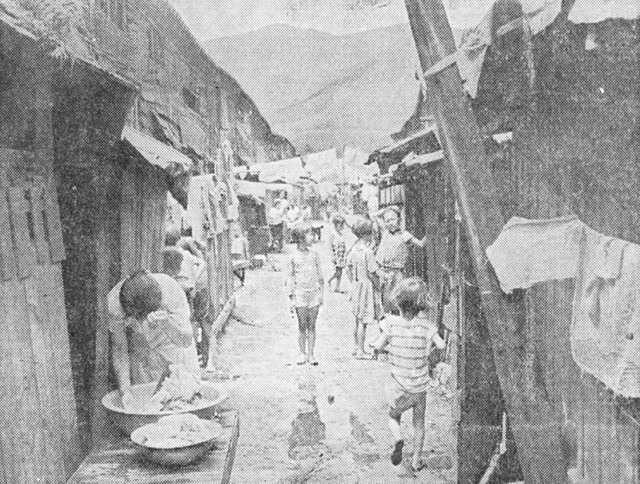

Some of the photographs taken by Yi Myŏngtong in the serial column “Reality,” deviated from those that presented universal and humanistic themes. Rather, they represented the marginalized identities of those who did not belong to the majority in the 1960s. Yi Myŏngtong had taken one such photograph on August 28, five days before publishing the image of the old man (fig. 10).

Standing in the middle of the street, Yi took a photo of buildings on both sides of the road and people on the street. The image looks like it was capturing an artless scene of mundane life. It is evident that this town was not an organized place, as the buildings are made of fragile wooden panels and all the children are walking barefoot. There is not a single adult male figure in the frame; there are only children and a woman who is washing clothes with her torso bent. This poor village was located in Masan, a region was inhabited by the Koreans who returned from Japan immediately after the Independence of Korea.

In 1945, when Korea was liberated from Japan, many Koreans who were living in Japan returned to Korea. Dreaming of a new life, they escaped from Japan where overt discrimination against the Koreans had been sustained during the colonial era. However, for eighteen years, until the regime changed for the third time, they had been ignored by the Korean government and had not received any support. According to the caption on the image, while “they came back from Japan with the delight of taking their motherland back,” they were “literally emancipated refugees, and this was like an asylum for the former Korean residents in Japan, an asylum which consisted of seven big warehouses where 1,711 people lived.”[48] The warehouses were divided into small rooms with partitions. “It is like a pigsty,” reported the Tonga ilbo column, and the only administrative signs were white posts signifying the number of members in each family. In an interview, a resident said “if I were able to go back to Japan on foot, then I would, even though I might die on the way.”[49] However, they were in a deadlock; 1963 was before the reconciliation between Korea and Japan, which happened in 1965, so they could not go back to Japan.

1963 was the year when Park Chung-hee’s military government carried forward the Korean-Japanese Peace Conference to sign a treaty to improve relations between Japan and Korea. Since it was based on the idea that Japan would provide South Korea with economic aid and in return Korea would never demand compensation for the colonial past, many criticized the government’s diplomacy, citing it as a humiliating decision. For instance, on August 1, 1963, leaflets opposing the Korean-Japanese summit were distributed in front of City Hall in Seoul.[50] While the assembly proposed to discuss the conference after the Presidential election, the government announced that the conference would be held no later than 1963.[51] Although the conference was ultimately delayed until 1965, in 1963 there was already a lot of debate surrounding the historical event. In the midst of this political context, Yi Myŏngtong’s photograph of the people who had returned from Japan, which was published on August 28, represented those who had been highly marginalized in the debate when in fact they were more directly affected than any of the other participants. The image, which is likely to be regarded as typical of saenghwalchuŭi sajin, touches on a sensitive social issue, and at the same time, it creates tension by representing people who had been marginalized in the Korea–Japan negotiations.

The above-mentioned photographs lead us to reconsider how to interpret the saenghwalchuŭi style photographs, or the “documentary” photographs produced in the 1950s and the 1960s. The photographs, produced by a group of photographers who attempted to depict everyday life, including Yi Myŏngtong, have been regarded as either photographs that were developed within the saenghwalchuŭi discourse bereft of social critique or photographs for newspapers committed to photo-journalism. However, even though these images were published in newspapers, it is misleading to claim that they only had journalistic functions, or that they were merely capturing moments of human life with a humanist gaze. Whether explicitly or implicitly, they made commentaries on the historical events of their time, showing us how a photograph can function as social critique.

Conclusion

The project of the historicization of Korean documentary photography has attracted the attention of many photography historians who have attempted to examine the genealogy of Korean photography. In this paper, I have examined the emergence of “realism photography” (riŏllijŭm sajin) in the 1940s and “everyday life photography” (saenghwalchuŭi sajin) in the 1950s and the 60s. There is a radical discontinuity between two different types of “documentary” photography—one influenced by Marxism-Leninism, and the other produced under the anti-communist sentiments that came to prominence following the Korean War. This discontinuity consequently opens up more space to examine the discourses within which saenghwalchuŭi sajin had been produced, promoted, and circulated. Particularly the implications carried by the term “everyday life,” saenghwal, during the colonial era and the post-independence era, should be more thoroughly examined. As I have argued, the possibility of social critique abounds in images associated with saenghwalchuŭi sajin, deviating from the common interpretation of these images as merely capturing a moment of human life. This deviation is particularly important as the current historiography in South Korea has found social critique within Marxist-inspired “realist photography” but has ignored the social critique of “everyday life style photographs.” Based on a localized interpretation of “documentary” photography, this paper not only revises the current historiography of photography in South Korea but also reveals the heterogeneity of Korean “documentary” photography.

Kaeun Park is a PhD candidate in Art History and Criticism at Stony Brook University, with a research focus on photography and visual culture in postwar South Korea.

Author's Note: I would like to sincerely thank John Tagg for his guidance throughout my research, at SUNY Binghamton, on this project.

Notes

Im Ŭngsik, Korean Photography that I’ve walked through — Memoirs of Im Ŭngsik (Seoul: Nunbit, 1999), 138–139. (Unless otherwise noted, all translations from Korean are the author’s.)

Documentary emerged in the late 1920s and early 1930s in a particular discursive frame. The generalized use of the historically specific term in the history of photography has robbed it of its specificity. I place the term in quotation marks to mark this difference, not least since my argument here rests on drawing precise historical terminological distinctions.

“Realism photography” (riŏllijum sajin) is a historical term which has been in use in South Korea since the 1950s. There are two terms for “realism” in Korean: riŏllijŭm and sashilchŭui. Many use the two terms interchangeably. In this essay I use the term riŏllijŭm sajin. This is because not only was it the more frequently used term during the 1950s and 1960s, but it is also the term which has been almost exclusively used in current academic literature in photography among historians. I suggest that the stereotypical notions of “social critique” from Marxism-Leninism theory and the binary frame of “transparent representation versus subjective expression” have molded the notion of “Realism Photography” (Riŏllijŭm Sajin) in Korea. In my paper, I have attempted to explain a specific discourse related to the usage of riŏllijŭm in the late 1940s. I argue that there is no “Realism Photography” (Riŏllijŭm Sajin) or “documentary” photography as such, which encompasses both riŏllijŭm sajin in the 1940s and saenghwalchŭui sajin.

Ch’oe Pongrim, “Reconsidering Everyday Life Photography,” Photography + Culture 8 (2014), 2–6.

Pak Chonghyŏn, “A Study on the South Korean Realism Photography and the debates on Korean Photography History,” Korean Studies Institute (2014), 169–178.

Ch’oe Pongrim, “Reconsidering Everyday Life Photography,” Photography + Culture 8 (2014), 2–6.

Yi T’aeung, wall text in Im Sŏkche’s first solo exhibition brochure, 1948.

Im Hwa, “Reconsideration of Realism,” Tonga ilbo (10 October 1937–14 October 1937). At the Seventh Communist International, which was held in Moscow from July 25 through August 20, the policy of the Popular Front was officially announced. In 1935, the policy was introduced to Koreans by writers such as Chŏng Insŏp. However, some literary historians such as Kim Yŭnt’ae claim that explicit comments on the Popular Front have not been found yet in Im Hwa’s writings. It is difficult to say that Im Hwa was influenced by the policies of the Popular Front. Nevertheless, many literary historians such as Ha Chŏngil argue that Im Hwa’s essays in the late 1930s indirectly implied the idea of building a broad populist alliance against Nazism. Since there are still ongoing debates on the sense in which Im Hwa used literary terms including “realism (riŏllijŭm/sashilchŭui)” and “social realism,” I focus here only on the fact that his usage of realism was related to Marxist aesthetic theory, and some of his works show the representation of the laboring class. See Kim Yŭnt’ae, “Theory of Im Hwa and Kim Kirim,” in Study on Im Hwa’s Writings II (Seoul: Somyŏng ch’ulp’an, 2013), 85; Ha Chŏngil, “Development of Social Realism Theory and the Popular Front in the Late 1930s,” Creation and Criticism vol. 19 (1991), 321–347.

Son Yukyŏng, “The Position of Subject in Im-Hwa’s Materialism,” The Journal of Korean Modern Literature vol. 24 (2008), 213–243.

For example, see his poem My Brother and Brazier, https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/my-brother-and-brazier, accessed 20 September 2019 (translated by Shin Chiwŏn).

Ch’oe Pongrim, “Korean Photography History through Historical Documents,” Photography + Culture vol. 1 (2010), 5.

“Good News for Pier Workers—Raising the Ratio of Profit to 2:8,” Kyŏnghyang shinmun (6 July 1948); “Issue on Cargo Work in Pusan,” Tonga ilbo (6 July 1948).

The division of Korea began with the 1945 Allied victory in World War II, ending Japan’s 35-year occupation of Korea. The Soviet Union occupied the north of Korea, and the United States occupied the south. With the ongoing Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union failed to unify the peninsula. In 1948, in South Korea, UN-supervised elections were held in South Korea and Rhee won the election. It led to the establishment of the Republic of Korea (South Korea), which was followed by the establishment of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in North Korea.

Ku Wangsam, “On the Issue of Realism in Photography,” Tonga ilbo (17 February 1955).

Im Ŭngsik, “Photography’s Present and Future — For the Production of Everyday Life Photography,” Kyŏnghyang shinmun (10 June 1955).

Im Ŭngsik, “Current Tendencies of Contemporary Photography,” Tonga ilbo (18 May 1961).

Yu Pyŏngyong, “A Study on ‘Realism’ in Korean Photography in the 1960s,” MA Thesis, Sangmyŏng University (2012), 15.

Ch’oe Pongrim, “Reconsidering Everyday Life Photography of Im Eing-sik,” Photography + Culture Vol. 8 (2014), 5.

Pak P’yŏngchong, “Amateur Photography Groups and Their Discourses during the 1950s–1960s,” Sajin + Munhwa vol. 12 (2016), 18.

Yi Hyŏngrok, Photographs of Yi Hyŏngrok (Seoul: Nunbit, 2009), 154.

Im Ŭngsik, “Formation of Korean Photography Scene and Its Problems,” Art and Everyday Life (October 1977), 77–87.

Pak Chusŏk, “Korean Photography in the 1950s and The Family of Man,” Journal of Korean Modern and Contemporary Art History Vol. 14 (2005), 64.

Im Ŭngsik , “An Epic Poem of Peace and Love, The Family of Man,” Idae hakpo (24 April 1957).

Pak Chusŏk, “Korean Photography in the 1950s and The Family of Man,” Journal of Korean Modern and Contemporary Art History Vol. 14 (2005), 67.

Allan Sekula, “The Traffic in Photographs,” Photography Against the Grain, (Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1984), 77–101.

Yu Pyŏngyong, “A Study on ‘Realism’ in Korean Photography in the 1960s,” MA Thesis, Sangmyŏng University (2012), 31.

Yi Myŏngtong, “Humanism Spirit of Artists,” Tonga ilbo (11 June 1955).

Im Ŭngsik, “Effort by New Artists Was Distinct, Quality Was Plain” Tonga ilbo (20 October 1964).

Ku Wangsam, “Problems of Korean Photography,” Tonga ilbo (29 October 1963).

Shin Hyŏnkuk, “Being Afraid of ... — Acceptance Comment,” Tonga ilbo (31 October 1963).

Ku Wangsam, “Lacking Subjective Projections,” Tonga ilbo (26 June 1965).

Im Ŭngsik , “Regarding Authenticity as Important,” Tonga ilbo (15 June 1967).

Im Ŭngsik , “Comments on the Third International Photography Salon,” Tonga ilbo (22 February 1968).

Pak Chusŏk, “Korean Photography in the 1950s and The Family of Man,” Journal of Korean Modern and Contemporary Art History Vol. 14 (2005), 50.

Oh Miil, “Campaign for the Improvement of Living Conditions and Korean People’s Ordinary Life in a National Mobilization System,” Journal of Korean Independence Movement Studies vol. 39 (2011), 235–277.

“Rapid Execution of Improving Everyday Life,” Kyŏnghyang shinmun (28 November 1948).

Yu Hyŏkin and Yi Myŏngtong, “Reality — Slash-and-Burn Farmer on Mt. Chiri,” Tonga ilbo (2 September 1963).

“Negotiating Presidential Candidacy in the People’s Party—A Shocking Moment,” Tonga ilbo (2 September 1963).

Yu Hyŏkin and Yi Myŏngtong, “Reality—Returned Koreans’ Village in Masan,” Tonga ilbo (28 August 1963).

“Pamphlets Against the Korean-Japanese Conference in front of the City Hall,” Tonga ilbo (1 August 1963).

“The Korean–Japanese Conference Will be Held by This Year,” Tonga ilbo (23 August 1963).