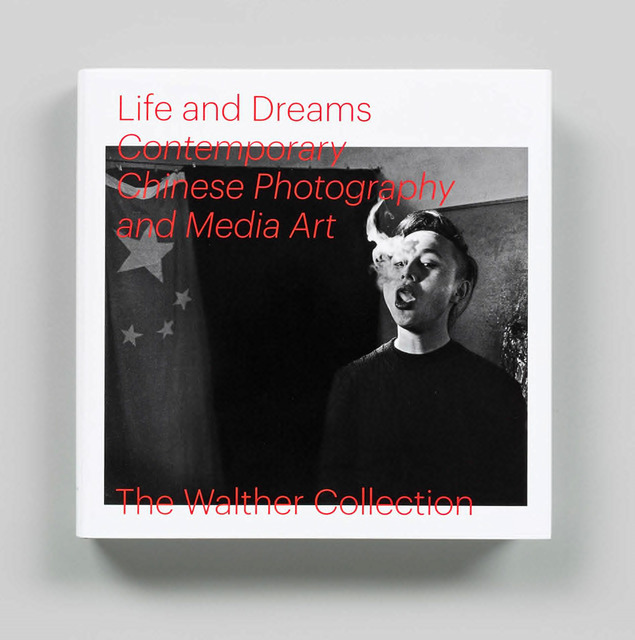

Christopher Phillips and Wu Hung (eds.), Life and Dreams: Contemporary Chinese Photography and Media

ISBN: 978-3-95829-490-5

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Life and Dreams: Contemporary Chinese Photography and Media bundles together what has come to be regarded as an iconic period in the making of photography, performance art, and new media (video, film, animation) in contemporary China. The collection of works and essays gathered in the catalogue, documenting an exhibition held at the Walther Collection in Neu-Ulm and a symposium at New York University in 2018, are the result of Artur Walther’s interest in post-Tiananmen mainland China, and reflect his studio visits to artists who emerged in the 1990s and the early 2000s before he turned his attention to photography in Africa. As a result, the 83 works in the collection, which are organized chronologically in the catalogue, present a concentrated period of activity between 1987 and 2017.

Elegantly designed with an updated bibliography, brief and useful biographies, compact and incisive catalogue entries, and republished essays from difficult-to-locate sources, Life and Dreams is no idiosyncratic or offbeat look at contemporary media art in China. Instead, the selected artists within are now accepted as near-canonical figures, and each artistic practice is exemplified by one or two iconic works. Several short essays, previously published in other venues, are collected for convenience here, including two essays by Wu Hung on Rong Rong in Beijing’s East Village and the New Photo journal, a curatorial statement on avant-garde photography by Rong Rong, an essay by the curator Karen Smith on Zhang Hai’er, an artist’s statement by Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong, Christopher Phillips on Yang Fudong’s East of Que Village, and a conversation between Wu Hung and Yang Fudong. With a more helpful apparatus than the usual biennial catalogue, Life and Dreams will be very useful for teaching, offering accessible, clearly written, and historically considered essays concentrated within an accessible volume.

Many of the photo-based works in Walther’s collection, such as Song Dong’s Printing on Water and Zhang Peili’s Water (Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary), are now mainstays of survey textbooks, permanent collections of contemporary art in museums, and milestones that punctuate major retrospective shows. A few notable additions to a roster largely comprised of artists born under the Cultural Revolution are younger artists who have become identified with animation and video in recent years: Sun Xun’s kinetic animations, Lu Yang’s glossy neurological loops, and Hao Jingban’s studies of ballroom dance. Their inclusion suggests the continuity of what Phillips and Wu offer as splintering, yet intersecting themes in this recent history of media in contemporary China, one that takes photography, video, and performance as refracting the social and political contexts of post-Mao and early Reform-era China.

In some ways, Life and Dreams retreads some of the groundbreaking territory covered by Wu Hung and Christopher Phillips’ previous collaboration, Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China (2004). The five narrative strands offered in Life and Dreams have firmed up as repeating themes throughout Wu’s prolific curatorial projects, essays of art criticism, and surveys of contemporary Chinese art, spanning the imbrication of performance art and photography, mediations of art historical references, explosive urbanization, reflections upon the socialist past, and gendered, sexual, and artistic identities.

Where Life and Dreams diverges from its predecessor is its largely retrospective tone. When Between Past and Future came out, its publication was part of a heady period of intensified artistic production, Euramerican curatorial attention, and market investment during the run-up to the Olympics. Life and Dreams describes a more established landscape: in his forward, Walther sets his collecting within recent exhibitions of contemporary Chinese photography, Phillips gives a overview of the history of photography in China, while a discussion between Phillips, Walther, and Wu reflects upon the potential for writing a history of photography in contemporary China. As Phillips observes, a generational gap has opened up a sense of periodization between artists of postsocialist China, born during the Cultural Revolution, and globalized China, born during the Reform era, as well as their reference points: “We see totally professional artists who are the products of an absolutely predictable art education system that is no different from anywhere else in the world. However, in a few of the younger artists I have met I do see some faint echoes of those artists, who in the 1980s and ’90s were ready to dare everything and make it resonate in their art.”

The three original essays, a careful tracing of Mo Yi’s body of work by James D. Poborsa, Stephanie H. Tung’s tightly contextualized examination of Zhuang Hui’s One and Thirty, and Xin Wang on what some critics have started to call post-Internet art suggest, in a diffuse way, the future directions of the field. Both Poborsa and Tung’s essays provide much-needed biographical contexts that are ultimately concerned with the artists’ contestation of state power, or what Tung characterizes as a monolithic sense of “certain social hierarchies and class structures already extant in Chinese society.” Xin Wang’s provocation, on the other hand, to provide a “future-oriented exploration rather than an art historical overview,” acknowledges a wholly different set of contexts, one in which the social includes notions of the West or the state, but also expands outward to engage with the rapidly evolving media environment of present-day China, a large-scale experiment with the penetration of state-protected and state-sponsored digital technologies and social media into everyday life that has undeniably created a new model of networked society.

Life and Dreams offers a moment to reflect upon the potential of embedding experimental artists within a media history of early Reform-era China. While the reader is left with a strong sense that artists exploited the indexicality of camera-based practices in order to expose hegemonic structures of state and society, the time is ripe for an explanation of the shifting media environment of early Reform-era China, especially in light of recent developments in both contemporary social media and Mao-era media studies. Questions of changes in viewing habits and ownership of viewing devices, access and availability of equipment, and conceptualizations of the relationship between media and society might build upon the incipient study of lens-based practices, and help answer the question, posed by the authors of this catalogue: what is particular to the history of media in contemporary China?

Christine I. Ho is Assistant Professor of East Asian art history in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her writing focuses on modern and contemporary Chinese art, and her current research project examines the history, theory, and practice of collective art production in twentieth-century China.