Joachim K. Bautze, Unseen Siam: Early Photography 1860–1910.

ISBN: 978-616-7339-66-5

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

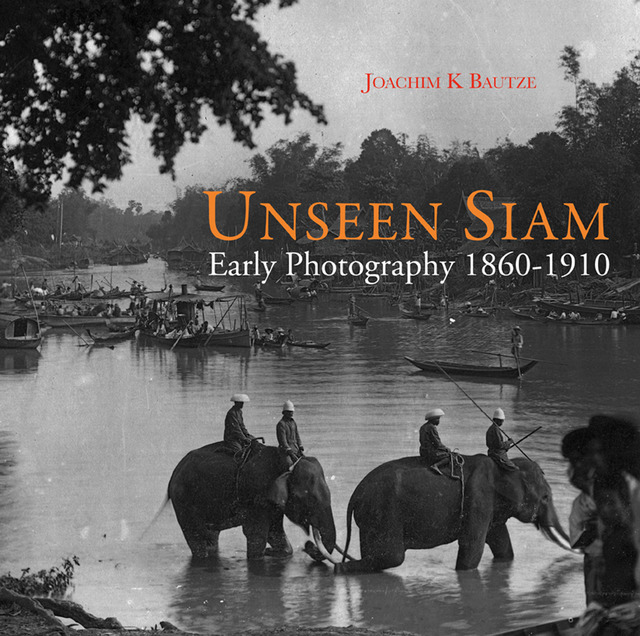

This gorgeously produced, oversized publication is an unusual combination of coffee-table book and exhibition catalogue. Showcasing large-scale images — many of which are heretofore unpublished — the volume dazzles the reader with many full-page (and double-page) renderings of images rarely seen in their original form, much less accompanied by their complete source information. On that count alone, the book makes an invaluable contribution. On other counts, however, this otherwise sumptuous collection frustrates the reader seeking greater contextualization of both the images and their makers.

The book’s focus on views of Siam through an overwhelmingly European gaze is ameliorated slightly by the foreword offered by the famed Thai collector and historian Anake Nawikkamune. He rightly points out the importance of the book in “building a tunnel to connect all the knowledge” between Asian viewers and the images contained in European archives, which are well-nigh inaccessible to most Asian scholars, requiring as they do not only expensive travel to the European capitals where such images live, but also linguistic ability in numerous Western languages (German, French, Portuguese, and English at the very least). Thus the collection and publication of such photographs provides a very real service to Thai scholars both within Thailand and around the globe, for whom many of these images will seem already familiar, though their dates, origins, and authors typically are not.

The problem begins with the way the project is (or in this case, isn’t) framed. In his introduction, Bautze opens with a brief tracing of European photographic history before turning his attention to Siam (Thailand) and the pictures in the book. “Almost all the photographs catalogued and illustrated in this volume were, at the time of being digitally? [sic] recorded, in European collections, most of them in Germany, many in Belgium, several in France and Britain with some in Austria and the Netherlands. A few are kept in the US and are now part of the public domain.” As to the photographers Bautze selected: “Each of the photographers featured in this book was introduced to the reigning monarch . . . in Bangkok and hence had the opportunity to take pictures of the unique and spectacular features Siam had to offer.” (p. 12) But soon comes a significant caveat: “The photographers documented here were not the only ones in Siam, several others were known, but their pictures are not easily available in Europe.” (p. 13) The selection pointedly excludes the voluminous holdings of the Thai national archives and any other collections within Thailand, many of which remain “unseen in Thailand” as well.

So, how exactly were the photographers in this volume chosen? This question is not answered here, nor are the guiding principles for the selection of images or photographers more clearly defined elsewhere in the text. The author does not appear to be making an attempt to completely survey European and American archives or collections for photographs of Siam; if there are additional images or collections not selected for inclusion, they are not mentioned here. Nor is it clear whether there were other Western “court photographers” operative in Siam, as a survey of local directories would surely show. The preponderance of German photographers represented (seven of the volume’s fifteen) remains unexplained and unexplored. Merely a few lines of additional explanatory text would have gone a long way to address any questions that arise for the author’s fellow researchers and scholars who would like to further pursue the “in depth analysis of the rituals and events depicted” mentioned by Bautze.

But these quibbles aside, it is difficult to resist the treasure trove of images awaiting exploration in the rest of the book. The fifteen chapters work chronologically from the earliest photographers in Siam (ca. 1845) to around 1910. The timeline begins during the reign of King Mongkut (r. 1851–68) with the French photographer Abbé Larnaudie (active 1845–61), assistant to the Catholic bishop Pallegoix; he is followed by Fedor Jagor (German, arr. 1861), Pierre Rossier (French, active 1862–63), and Carl Bismark (Prussian, active 1861–62). Rossier’s most famous pictures are those of three “Amazons” (see p. 55, plates 7a and 7b), three of King Mongkut’s consorts who dressed in hybridized outfits of tam-o’-shanters, military jackets, argyle stockings, and Scottish kilts while guarding him on horseback. From this group of photographers came several of the best-known images of King Mongkut and his principal wife, Queen Thepsirin, many of which were originally published as engravings (halftone reproduction of photographs had not yet been invented). As engraved adaptations of photographs rarely bore the names of the images’ creators, many of them circulated widely among European audiences without the original photographers being properly credited. Several of the images in these chapters will appear familiar to students and scholars of Thai history: The engravings have long circulated in texts such as Anna Leonowens’s The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) and Henri Mouhot’s Le Tour du Monde (1863).

The fifth and sixth chapters are populated by two somewhat better-known figures: the Sino-Thai photographer Francis Chit (active 1863–80s) and the Scotsman John Thomson (1862–72). The book’s first Siamese-born photographer (1830), Chit had a long tenure as photographer to Thai elites and cataloguer of Siam’s landscapes. Accordingly, his pictures turn up across a number of European collections, from the Quai de Branly, in France, to the P. Laycock, in Belgium, to those of the P&G and Günter Heil, in Berlin. And no wonder: They capture temples, funerary rituals, elephants, monks, royal children, and prominent figures, such as Princess Thipkesorn of Chiang Mai (plate 53, p. 127), for whom he produced cartes de visité from the 1870s onward. There are probably examples of Chit’s photographs in Russian archives, as he also recorded the official visit of Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich to Bangkok in 1891 (plates 63 and 64).

The author need not have hedged his bets by saying that “[i]t is probably no exaggeration to say that F. Chit was in a league of his own.” Likewise, John Thomson’s images have attained a level of fame well beyond the field of Siamese photography — particularly those of his travels through Siam and Cambodia, especially Angkor Wat between 1866 and 1872. These pictures found their way into many a souvenir collection of expats and Western travelers to the region during the era.

Chapters seven through nine center on three (more) German photographers: Henry Schüren, Gustave Lambert, and Max Martin. Although the slender amount of information about Schüren and Martin understandably cries out for more examples of their European work to supplement the Siamese images available, the number of European images in the Lambert chapter is somewhat mystifying, as his body of Siamese work (set off puzzlingly in its own section labeled “The Views”) was extensive. Nonetheless, there are interesting and historically significant photographs to be found here: Among Schüren’s work are early portraits of young King Chulalongkorn (r. 1873–1910) as well as images of the royal “summer palace,” at Bang Pa-In, Ayutthaya, and various temples around Bangkok.

Chapters ten through twelve provide a bit more breadth, representing a Briton (William Kennett Loftus), a German (Fritz Schumann), and a Portuguese photographer (Joaquim Antonio), respectively. The Loftus name may be most familiar to historians of Thailand, as W.K. was named after his explorer-geologist father and his uncle Alfred John Loftus (1836–99) was “an inventor and hydrographer” employed by King Chulalongkorn in Siam in the same era. It also appears that Loftus can be linked to Lambert, whose photo studio and equipment he took over in 1882. According to Bautze, Loftus’s images are not only remarkable for their content — he had obtained special permission to photograph royal ceremonies and Wat Phra Kaeo’s interior — but also for their large print size, 12 x 14 inches. Contemporary scholars are lucky that more than fifty of Loftus’s pictures in the Pitt-Rivers Collection, at Oxford, are digitized and available online “with full documentation of [their] provenance.” (p. 216)

It is Loftus’s eminent worthiness to be included in the book that makes the presence of Fritz Schumann — immediately following him, no less! — a bit jarring. Even Bautze himself seems a bit apologetic about it, opening the Schumann chapter’s text with “It is ironic that the photographer who was proudest of his royal Siamese appointment can boast hardly any Siamese photographs to his name.” (p. 235) Beyond a carte de visité featuring Prince Damrong (King Chulalongkorn’s most prominent brother), the remainder of the images reproduced are European examples: twenty-eight of them, which seems a bit excessive for a book on “unseen Siam[ese]” images.

This is atoned for in the chapter on Joaquim Antonio, who was born in Macao in 1857, which makes him the second native Asian photographer featured in the volume. Whether he was European or Asian is not explained; in any event, Antonio earned a significant place in Southeast Asian photography. He was the first photographer to open a studio in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), in 1901, and his work was recognized in the 1902–03 Hanoi Exhibition, where his views of Siam “and other countries” received a silver medal (p. 247). Bautze’s description of Antonio’s work further intrigues us: “Nobody seemed to be photographically closer to the people of Siam than [he was]. . . Antonio excelled in capturing everyday life, the country folk and the gentry.” (Ibid.)

In addition to rural scenes and a set of posed portraits of “women of Siam,” some of Antonio’s contributions are official shots of the Siamese king and various ministers opening a section of railway line in 1903 (plate 12), ancient ruins at Lopburi (plates 17 and 18), and a charming image of Queen Saowapha (plate 25), posed reviewing documents at a desk, an image that marked her role as the first female regent during King Chulalongkorn’s visit to Europe in 1897 (p. 257) Among Antonio’s European subjects, we find the Belgians Emile and Denise Jottrand, resident for several years while Emile acted as a legal adviser to the king (plate 104, p. 283). But it is really the more than one hundred (!) Siamese images here that warrant wider awareness of Antonio’s work: Many feature villagers, families, merchants, river scenes, and elephants. As such, they are a far clearer reflection of “real” Siamese people and daily life than was typically viewed through photographers’ lenses during this period.

The three final chapters cover the Germans Robert Lenz and Emil Groote and the Japanese Kaishu Isonaga. The Lenz name and pictures are well known to students of nineteenth-century Siamese history: He became the most prominent photographer in Bangkok and was well loved by the Siamese royals, who frequently utilized his services. Lenz’s work in Bangkok began with short visits from his Singapore studio in 1893, marketing his range of “artistic” and novelty images and “collodion-chloride process . . . pictures which do not fade.” (p. 291) In 1898, Lenz moved his studio to Bangkok permanently when he became the official photographer to the king of Siam. The pictures collected here show some of the spectacular portrait work that Lenz did during his ten years in Bangkok (1989–1907): portraits of King Chulalongkorn and his high queens, children, and ministers posed against sumptuous draperies, painted scenes, and plush carpets and surrounded by Western furnishings of the latest styles. Plates 30–100, however, reflect Lenz’s skill as a landscape photographer and provide historical images of the royal palace (plates 47–49), important temples (plates 55–66), river scenes (plates 67–86), dancers (plates 92–94), people (plates 87–91 and 99–101), and elephants (plates 106–16). Lenz should be ranked with Francis Chit among the most historically important photographers in nineteenth-century Siam.

Lenz’s successor, Emil Groote, did not leave nearly such a body of work. Perhaps his most famous photographs are of traditional dancers (plates 5–7), one of which became the cover image for the Thai scholar Mattani Rutnin’s well-known text Dance, Drama, and Theatre in Thailand: The Process of Development and Modernization (1993). The brief final chapter is on the Japanese emigré Kaishu Isonaga, who also worked briefly with Lenz in 1907 before opening his own studio in Bangkok. Isonaga’s images appear to be mainly of Europeans living in Bangkok, including (once again) the Jottrands. There are also portraits of a German family, the Spethmanns, which contain an intriguing image of their eight-year-old daughter, Ilse, dressed in Siamese chongkrabaen trousers, with bracelets around her ankles and her hair tied up in a topknot (plate 3, p. 352). Ilse’s playful smile in the “costume” photograph contrasts with her subdued expression in the adjacent formal family portrait, in which she wears a dress of white lace, shoes, and a hat.

The author did not know, as I do, that Isonaga played another important role in the genealogy of Siamese photography: training his fellow Japanese emigré Morinosuke Tanaka (arr. Bangkok 1900), who became the first commercial photographer in northern Thailand. He came to Lamphun in 1903 and moved later to Chiang Mai, where he took royal portraits — much in the style of Lenz — of Phra Rachaya Chao Dara Rasami, the fifth-highest of King Chulalongkorn’s queens, when she visited the city in 1909. This, for me, represents the shortcoming of Bautze’s otherwise visually dazzling and detail-laden text: the lack of context, of attachment to the larger historical forces at work. Why so many German photographers coming to Siam? Why so few Asian-born ones? And what happened after Isonaga — why bookend the narrative with that particular artist? (Perhaps King Chulalongkorn’s death, in 1910, represents the meaningful marker on that count.) Doubtless, photography began to take off in Siam in the 1920s, necessitating future volumes on that work.

Somewhere between Anake Nawikkamune’s Thai-language scholarship on Thai photographic history and Bautze’s survey of the “unseen” Siamese images floating around in archives and collections beyond Thailand, there is a text — one that does not yet exist — that tells the whole story: of all the photography that occurred in Siam from its advent onward, rendered by both Europeans and Thais. (An English-language translation of Anake’s encyclopedic volume on Thai photography would make an excellent start.) But until such a project is possible, Bautze’s text succeeds in “building a tunnel” between the two continents and bodies of work that is much needed indeed.

Leslie A. Castro-Woodhouse, an independent scholar, holds a PhD in Southeast Asian history from the University of California Berkeley, and is former editor of Asia Pacific Perspectives at the University of San Francisco. She is the author of “Concubines with Cameras: Royal Siamese Consorts Picturing Femininity and Ethnic Difference in Early 20th Century Siam,” published in Trans Asia Photography Review 2:2.