Creating a Space for Performing Tibetan Identities: A Curatorial Commentary

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

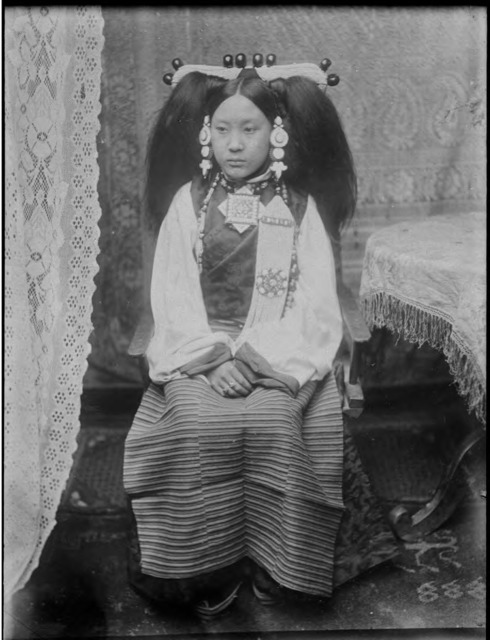

Fig. 1. Nyema Droma, Double Portrait of Kesang Ball, London, 2018, 81 X 59 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 1. Nyema Droma, Double Portrait of Kesang Ball, London, 2018, 81 X 59 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.Performing Tibetan Identities is an exhibition of portrait photographs created in 2018 by Nyema Droma, a multitalented young Tibetan woman from Lhasa, which is in the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China. Her depictions of other youthful Tibetans, whether based in the Tibetan-speaking areas of China or the European hubs of the Tibetan diaspora, offer a powerful reflection on the lives they lead and the choices they make when performing for her camera. This essay introduces examples from that body of work, the concepts and processes behind its creation, and the setting in which it was devised and displayed: the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxford, United Kingdom — as this exhibition not only offers a commentary on the complexities of contemporary Tibetan identity formation, but is also a site-specific artwork and the product of an engagement with a very particular kind of visual archive. In co-curating an intervention in the heart of an ethnographic museum and interacting with its photographic collections, Nyema Droma and I sought to insert a dynamic contemporaneity into a historic exhibition space and to reinterpret a set of images produced by British travelers to Tibet in the colonial period. The result is designed to critique the history of outsiders’ representations of Tibet and the visual stereotypes it has generated while celebrating alternative ways of imagining Tibetan culture from the perspective of Tibetans themselves.

Fig. 2. Installation of Nyema Droma’s work in the main hall of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, 2018. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 2. Installation of Nyema Droma’s work in the main hall of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, 2018. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.“Type”/Stereotype

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, control of the photographic documentation of Tibet has largely been dominated by individuals from outside its borders. During that time, portraits of Tibetans have been especially keenly accumulated and then commandeered into a wide range of visual narratives composed by non-Tibetans. At one end of the spectrum are the Orientalist notions of “mystical” Tibet that underpin the Shangri-La myth in the West. At the other, arising in the East, come visions of a Tibet absorbed into the People’s Republic of China after 1951 and transformed by Maoism during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) and its aftermath. In between, as discussed in my book Photography and Tibet, lie many other iterations constructed at particular times and places, and with specific purposes in mind.[1] Among these diverse agendas, one has special relevance for Nyema Droma’s activities at the Pitt Rivers Museum in 2018. It is the product of a scientific drive, conceived for the most part in Europe in the nineteenth century, to document human variation according to the principles of the emerging disciplines of physical anthropology and its cultural correlate, ethnology.

In this troubling exercise in classifying humanity along racial lines, individuals were subjected to a mode of photographic framing in which attention was drawn to variations in physiognomy and the material markers of ethnicity, religion, occupation, and so on. Such imagery proved useful for “colonialism and its forms of knowledge” but it was also swiftly popularized by commercial photographers who generated postcards and other mass-market imagery from the late nineteenth century on.[2] The genre became known as “type” photography, a complex and slippery category of image production in which images were produced with specific modes of consumption in mind.[3]

Beginning in the 1890s, innumerable examples of Tibetan “types” were created, with subjects posed to emphasize exoticism and difference from their non-Tibetan consumers. Since Tibet was notoriously difficult to access in the Victorian era, many of the earliest examples of such photography were actually staged in studios situated in the Himalayan foothills of British India. There, Tibetans who had lived in the vicinity for generations were induced to pose for European photographers, sometimes along with props and painted scenery but more often with a blank backdrop to accentuate the physical features of the “type” and the perceived strangeness of their apparel and artifacts. When published as postcards and inscribed with labels such as “Tibetan Lady,” “Buddhist Lama,” and “Thibetan Native,” the process of reducing an individual to a (stereo)type for the viewing pleasure of others was complete. However, all images processed and presented as “types” were, of course, originally portraits of certain individuals, rather than mere cyphers of ethnicity crafted for the viewing pleasure of others. One of the aims of Performing Tibetan Identities was to interrogate the latter by accentuating the agency and identities of the living individuals pictured by Nyema Droma.

The Photographic Archive

With its collection of more than 330,000 photographs dating back to the emergence of anthropological photography as a mode of record in the Victorian period, the Pitt Rivers Museum is a rich resource for researchers, artists, and indigenous scholars. Within that collection are some 7,600 photographic objects (prints, negatives, and albums) pertaining to Tibet. They were made by British photographers between 1900 and 1950 and constitute a hugely important visual record of Tibet as it was before the departure of the 14th Dalai Lama into exile in 1959 and the subsequent creation of the Tibetan diaspora. When Nyema Droma accepted a grant from the museum’s “Origins and Futures” program to become a visiting artist in 2018, it enabled her to come to Oxford from Tibet/China to study that material, including hundreds of portraits of Tibetans in which the legacy of “type” photography is visibly present. Encountering those pictures from a period long before she was born was a powerful stimulus for Droma’s work. It led to her first exhibition in a major museum outside China and made it possible for the Pitt Rivers to host a display that could subtly critique colonial-era photography of Tibet.

Fig. 4. Digital screen displaying historic photographs of Tibet from the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum alongside Nyema Droma’s installation. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 4. Digital screen displaying historic photographs of Tibet from the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum alongside Nyema Droma’s installation. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.The Photographer and Her Subjects

As a photographer, designer, curator, and entrepreneur, Nyema Droma is a leading light in the reinvention of Tibetan culture in her home city of Lhasa. Having studied at the London College of Fashion for three years, she is also a transnational figure with connections to Tibetan communities all over the world, with her finger firmly on the pulse of global trends in art, photography, and design. Although she was born in Lhasa, Droma was educated in Chengdu, a massive city with a mixed Chinese and Tibetan population, and a place where she recalls that her identity as a Tibetan was frequently queried by her Han classmates. On leaving school, Droma’s extraordinary tenacity and language skills made it possible for her to study in the United Kingdom. Over three years in London, between 2012 and 2015, Droma encountered other Tibetans who impressed her with their multilingualism and multiculturalism, and their ability to experiment and adapt to the local environment. She observed that British members of the Tibetan diaspora freely sampled from a vast array of street styles in music, food, and dress, while simultaneously engaging, to varying degrees, with their Tibetan heritage. On her return to Lhasa, she noticed a similar situation among the “trendy Tibetan youth” (as she puts it) and came to the realization that a cultural transition appeared to be under way there too, in which the global and the local (of a Tibetan/Chinese variety), were deeply entangled.

“Second-Generation” Tibetans

When beginning her project with the Pitt Rivers Museum, Droma decided to document this phenomenon in both Europe and China and to focus on individuals who, like herself, are “second-generation” Tibetans. She uses this term to describe those born after the dramatic changes that occurred in Tibet in the mid-twentieth century. To summarize (all too briefly): The year 1951 saw the so-called “Peaceful Liberation” of Tibet by the Chinese army, which initiated the process in which the majority of Tibetans became citizens of the People’s Republic. Since then, almost every aspect of their lives has become hybridized Sino-Tibetan, and most people are bilingual and bicultural. With the influx of Chinese workers and the concomitant rise of mixed marriages beginning in the 1960s, an increasing number are also biracial.

In 1959, after an uprising by Tibetans against the Chinese, the 14th Dalai Lama left Lhasa and sought sanctuary in India. Those who followed him into exile are now dispersed, in relatively small numbers, around the planet. The territory they previously called home no longer exists as a country, and the generations born in exile have either never been to “Tibet” or have great difficulty in visiting the birthplaces of their parents, which are now designated as being in China. In short, due to the vicissitudes of geopolitics, there are currently two Tibetan communities: the larger one located in the land of their forefathers but under a different name and the other scattered amid host nations, with a major hub in India, where the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan “government in exile” are based. Few individuals have the capacity to move between the two, and the (re)unification of the two communities in any form is rare.

Fig. 5. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Tenzin Nyendak, London, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 5. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Tenzin Nyendak, London, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Fig. 6. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Baizhen, Lhasa, China, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 6. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Baizhen, Lhasa, China, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.From the outset of her project at the Pitt Rivers, Nyema Droma sought to attempt a kind of (re)unification, and to demonstrate that young Tibetans have much in common, wherever in the world they find themselves. To that end, in spring 2018 she set up photo-shoots for her Tibetan contacts in London and Oxford. This procedure was then extended to three other cities in Europe: Paris, Amsterdam, and Zurich. On her return home, Droma did the same in Lhasa and Yushu, two Chinese cities with significant Tibetan populations. In all, she photographed more than thirty individuals. The selection we featured in the exhibit is unique in a museological context, in that it contains portraits of members of communities in both Europe and in China, and brings representatives of the Tibetan-speaking world into one space through the medium of photography and the techniques of contemporary art curation.

Fig. 7. Portraits by Nyema Droma displayed in the Long Gallery of the Pitt Rivers Museum, with TV monitor showing video of her interviews with individuals she photographed, 2018. Photograph: Ian Cartwright, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 7. Portraits by Nyema Droma displayed in the Long Gallery of the Pitt Rivers Museum, with TV monitor showing video of her interviews with individuals she photographed, 2018. Photograph: Ian Cartwright, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.An Intervention in the Empty Space

These two practices were combined as we conceived an installation for the main hall of the Pitt Rivers Museum, which is known as “the court.”[4] Covering three floors, the court encompasses the only large expanse of emptiness in a museum famously crammed with tens of thousands of objects that are organized according to the “typological” scheme specified by the museum’s founder, Augustus Pitt Rivers, in 1884 and are still displayed in Victorian-style cases. In its lack of objects, that void is alluring for both artists and curators. It is also highly visible, as all visitors to the museum will encounter it, even if they do not register it overtly. We therefore agreed to insert Droma’s two-dimensional images into this capacious, three-dimensional space in order to facilitate new ways for its audiences to experience the museum. Suspended at two levels and printed as double-sided banners at large scale, Droma’s work would be viewable from many vantage points around the museum space. With their vibrantly colored backdrops, the portrait banners also obliquely reference the strings of prayer flags that are ubiquitous in all locations of Tibetan religious practice. Traditionally, these flags are printed on cotton cloth in the five colors of the elements of Buddhist cosmology and placed at sites of sanctity or liminal points in the landscape, such as mountain passes and river crossings. However, in the Pitt Rivers installation, only green, red, yellow, and blue feature in the backdrops on the front side of Droma’s portraits and the omitted color, white, becomes the ground for her more monochromatic images on the reverse. These aesthetic choices reiterate the wider themes of acknowledging indigenous precedent and the black and white characteristics of archival photographic objects, while feeling at liberty to experiment with both.

Fig. 8. Reverse view of portraits by Nyema Droma installed as banners in the Pitt Rivers Museum, 2018. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 8. Reverse view of portraits by Nyema Droma installed as banners in the Pitt Rivers Museum, 2018. Photograph: John Cairns, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.Once installed in the court, Droma’s portraits were presented in dialogue with the vast array of objects from all time periods and regions of the world (including Tibet) that fill the Pitt Rivers Museum. Importantly, they would bring representations of Tibetan bodies into a place where, as in many other ethnographic museums founded in the nineteenth or twentieth century in Europe and North America, artifacts have been used to signify the cultures of others collectively, and to stand in for the people who originally made, owned, or used them. In the absence of those individuals, objects shoulder the burden of representation. This practice has sometimes led to museums being accused of forcing a timelessness and traditionalism onto both things and peoples: downplaying their histories, denying the capacity for change, and limiting the possibilities for contemporary engagement and resonance. Most egregiously from the perspective of current “decolonizing” agendas, the descendants of those who first created, utilized, or possessed the objects are still frequently absent from the museum, either in person or in any representational format. In addition, many people (among them members of the Tibetan community worldwide) are often simply unaware that their material heritage is conserved in a particular museum and/or they lack ready access to it. Digital projects, such as “The Tibet Album,” in which 6,000 photographs of Tibet from before 1950 have been made available in a website, is one of the methods that the Pitt Rivers has previously pursued in an attempt to alleviate such problems.[5] Performing Tibetan Identities is another effort to remedy the situation but one which takes the form of a creative intervention that makes Tibetan bodies and Tibetan agency hyper-visible in the museum. Since Droma’s photography is utterly contemporary in style, substance, and sensibility, it also undermines expectations of traditionalism that for generations have dogged not only museums of anthropology, but Tibetans as well.

Fig. 9. Nyema Droma and Clare Harris viewing glass plates and documentation in the Pitt Rivers Museum archive, 2018. Photograph: Philip Grover, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 9. Nyema Droma and Clare Harris viewing glass plates and documentation in the Pitt Rivers Museum archive, 2018. Photograph: Philip Grover, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.The Inspiration of the Archive

This theme is taken up most explicitly in the double-sided format in which Droma’s portraits are presented in the court. This novel design was the result of a session in the museum’s research area when we viewed original prints and negatives from the Pitt Rivers collection, including the glass plates produced by the British civil servant Charles Bell and his aide, Rabden Lepcha (who hailed from the Himalayan kingdom of Sikkim) in Tibet in 1920–21. They depict monks and laypeople of Lhasa and are often composed in a style reminiscent of the colonial-era “type” photography discussed earlier. In fact, when his long service as a senior figure in Anglo-Tibetan relations ended, Charles Bell used several of these studies to illustrate distinctions of class, religion, and ethnicity in the books he published on Tibetan society and history.

Fig. 10. Rabden Lepcha, Aristocratic Woman, Lhasa, 1920-1921, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.285.134.

Fig. 10. Rabden Lepcha, Aristocratic Woman, Lhasa, 1920-1921, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.285.134.When examining images of this sort in their raw state as glass negatives, however, they become less reducible to “type” and far less easily readable in general. The eyes of the viewer tend to struggle, while the mind tries to invert the negative into positive. Equally disorientating is the way the shape of a human body appears in white on the glass, resembling an apparition rather than a living being. Droma commented on this effect, but was most struck by the conversion from negative to positive. When a glass plate of a Tibetan monk was placed alongside its printed positive, she said it felt as though she was looking at two different people.

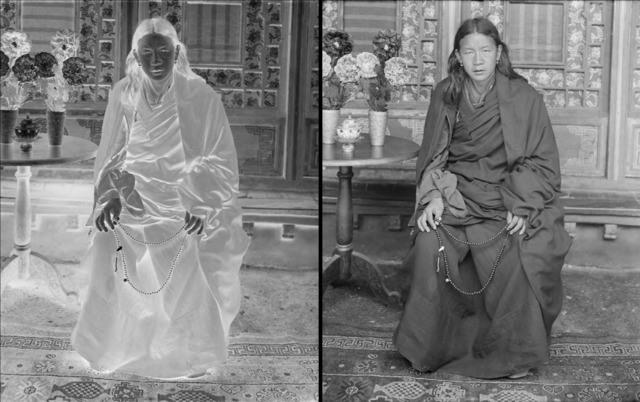

Fig. 11. Rabden Lepcha, A Nyingma Monk, Lhasa, 1920-1921, glass plate negative, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.225.1.Fig. 12. Rabden Lepcha, A Nyingma Monk, Lhasa, 1920-1921, glass plate positive, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.225.1.

Fig. 11. Rabden Lepcha, A Nyingma Monk, Lhasa, 1920-1921, glass plate negative, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.225.1.Fig. 12. Rabden Lepcha, A Nyingma Monk, Lhasa, 1920-1921, glass plate positive, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, from the collection of Charles Bell. Accession number: 1998.225.1.Positive/Negative

This revelation was the inspiration behind Droma’s decision to photograph members of the “second generation” of Tibetans twice and in different sartorial modes. She chose to combine the transformative effects of the conversion from negative to positive with a critique of the way in which “type” photography appeared to codify, even ossify, the visual representation of Tibetans by focusing on objects and dress as markers of ethnicity. Therefore, when Droma invited people to be photographed at her pop-up studios in Europe and China, they were asked to bring two outfits: their daily wear and more “traditional” garb. They were also requested to take along an item of particular significance to them. Each person would then be photographed in the dress she or he had selected and with their favored artifact.

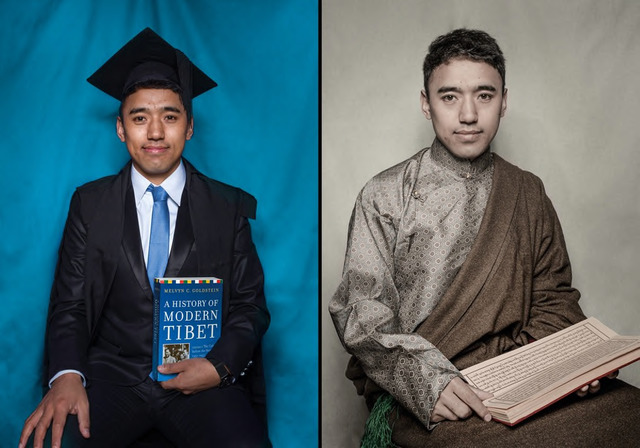

Fig. 13. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Darig Thokmay, Oxford, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 13. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Darig Thokmay, Oxford, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.To elaborate on just one example: Darig Thokmay arrived at his photo shoot with the mortarboard and gown of the University of Oxford, where he is currently studying Tibetan history He also brought a volume on that subject written in English by an American. For his second portrait, Thokmay wore a chuba, the long gown worn by both men and women in Tibet, and posed with a pecha, the style of book that has been used for printing religious texts in Tibetan for centuries. Given that Thokmay was born in Tibet, was first educated in a monastery there, and since escaping to exile has continued his studies in India, Poland, and the United Kingdom, his double portrait tells a poignant tale of a life divided between homeland and exile, as well as of the different modes in which Tibet’s history has been related. It also changes his appearance, just as the positives of the old glass negatives had led Droma to think she was looking at two different people. Thokmay’s transformation is made manifest not only through material accoutrements, but also in his countenance. In his color portrait, he appears smilingly confident; on the more monochrome reverse, his expression, although still proud, seems tinged with sadness.

Such outcomes indicate how Droma’s photographs function as “little theatres of self,” to use Elizabeth Edwards’s expression, where many facets of identity are performed and allusions to past, present, and future are intertwined.[6] These intimately biographical images, although devised with reference to an earlier essentializing mode of photography, demonstrate that no one can be reduced to a mere “type” and that identity is a complex intersectional matter in which factors such as gender, sexual orientation, religion, and cultural influences all intermingle. In short, each of Droma’s subjects construes her or his sense of Tibetan-ness quite differently for, as one them noted, there is ultimately “no such thing as a pure or rigid definition of being Tibetan.”.[7]

Fig. 14. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Tsering Thondrop, Lhasa, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 14. Nyema Droma, Double portrait of Tsering Thondrop, Lhasa, 2018, 168 x 120 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.How to Be Both

Although the double images in this exhibition could be interpreted simply as split between the “traditional” on one side and globalized modernity on the other, neither Droma nor the individuals she photographed took these to be mutually exclusive categories with only positive or negative connotations. Rather, Droma’s studies illustrate the potential to shuttle back and forth between options, or as one Tibetan visitor to the exhibition put it: They demonstrate “how to be both.” This phrase came from the mother of a teenage boy who was born and raised in Britain. She thanked Droma for showing a “third-generation” refugee that it was possible to be conscious and proud of his Tibetan heritage while also embracing a multitude of other influences.

Fig. 15. Nyema Droma, Double self-portraits, Lhasa, 2018, 38 x 27.5 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 15. Nyema Droma, Double self-portraits, Lhasa, 2018, 38 x 27.5 cm each, © Nyema Droma/Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.This response very much concurred with Droma’s intentions: She wanted her subjects to be seen as stylish, empowered agents of their own self-representation, and not as victims, either within the narratives of exile or in the politics of China. Above all, she sought to undermine stereotypes, whether generated by foreigners or Tibetans themselves. That point is most clearly made in the remarkable self-portraits Droma created for the show. In the first, she reveals her bare arms covered with tattoos: an especially unusual body modification for women in Tibet, both now and in the past. In the second, she adopts “traditional” male dress, wears a false beard and moustache, and carries her camera ostentatiously. Droma told me that this was because both guises were “beyond the imagination” of older generations of Tibetans, whose traditionalism does not allow for the possibility that a woman could be a photographer, an artist, or an individual with the capacity for radical self-reinvention. With this exceptional exhibition, there can be little doubt that Nyema Droma is all these things and much more.

Note

Performing Tibetan Identities: Photographic Portraits by Nyema Droma opened on 13 October 2018 and is on display at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, until 30 May 2019.

The exhibition was co-curated by Clare Harris and Nyema Droma. This essay was written in consultation with Nyema Droma and quotations from her are reproduced with her permission.

For more information about the exhibition, visit https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/event/performing-tibetan-identities.

Clare Harris is Professor of Visual Anthropology in the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography and Curator for Asian Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford. She has been the recipient of major research grants for her work on Tibetan visual/material culture and her award-winning publications include The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics and the Representation of Tibet (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Clare Harris, Photography and Tibet. London: Reaktion Books, 2016.

Bernard Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Although this curatorial essay is not the place to explore it, there is extensive critical literature on the production and consumption of “type” photography in the colonial period. My own publications on transcultural encounters between colonial-era photographers and their subjects seek to underscore the agency of the individuals who were reduced to “type” in the process. See, for example, “Photography in the Contact Zone’: Identifying Copresence and Agency in the Studios of Darjeeling,” in Transcultural Encounters in the Himalayan Borderlands, Markus Viehbeck (ed.). Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing, 2017, pages 95–120.

This was a particularly innovative feature of the exhibition that was complemented by a more conventional display in the museum’s Long Gallery, where we presented further portraits by Nyema Droma, a feedback area, and a TV screen showing the interviews she had filmed with her subjects.

Elizabeth Edwards, “‘Little Theatres of Self’: Thinking about the Social,” in James Fenton, Elizabeth Edwards, and Tom Phillips (eds.). We Are the People: Postcards from the Collection of Tom Phillips. London: National Portrait Gallery, 2004, page 29.

This comment comes from an interview Droma conducted with one of her subjects, Thupten Kelsang, a young man who was born in the Tibetan refugee community in India and is now studying at the University of Oxford. His interview was filmed and extracts from it were shown on a video monitor in the exhibition, along with excerpts from interviews with other individuals whom Droma had photographed.