Modern Family: The Transformation of the Family Photograph in Qajar Iran

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

During the Pahlavi Dynasty (1925–79), three genres of photographs dominated: state photographs, photojournalism, and family photographs, all of which become mirrors of the state, as the state gave rise to the “kingly citizen.”[1] One staple attributed to family photography was the representation of the heteronormative, nuclear family of wife-husband-children in typical bourgeois fashion, reflecting the desires of Reza Shah (r. 1925–41) to model his subjects as part of the modern, industrialized world. In studio photography as an institutionalized and regulated industry during the Pahlavi era,[2] heterosexual, married couples pose with their children, and in other photographs, couples show physical affection.[3] Photohistorian Reza Sheikh writes: “The ‘emancipation’ of women left its mark on family portraits. Whereas previously women had been conspicuously absent from family photographs, whether alone or next to their husbands and children they were now prominently present.”[4] Although more women did pose in family photographs, and heterosexual couples displayed for the camera more physical affection during the reign of Reza Shah, two observations remain. First, in studio photography, the poses and approaches did not vary much from those of the Qajar era (1785–1925) — a transitional period that Motarjemzadeh calls the “Grey Years” — in that many family photographs still conspicuously omitted the matriarchs, leaving only the father and his offspring. [5] Second, photographic depictions of a loving, heterosexual, nuclear family also began during the Qajar period in both studio and private family photographs of the elites, in particular those of Princess ʿEsmat al-Dowleh Qajar, the second daughter of the king Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1848–96), and of her immediate family.

ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s family photographs were some of the first Iranian photographs to imply romantic love, a heteronormative relationship between wife and husband, and the happiness of a nuclear family with cherished children between only two spouses. I am not suggesting that it was her family photographs explicitly that determined later family photographs of the early Pahlavi years, although she was an influential princess who helped run a successful photography studio in her home with her husband, Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (1856–1913). What I am arguing is that ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s photographs of her family recorded or reflected changes in the attitudes of what constituted marriage and children during the late Qajar Dynasty, especially with the elites, who were increasingly engaged with foreign contact and scrutiny. Earlier nineteenth-century family photographs, such as of the harem women of Nasir al-Din Shah, elicit “documentary” or “anthropological” labels rather than “family photographs.” Relying on Rosalind Krauss, the shah’s photographs slip through several discursive spaces, for example, state photographs, documentary photographs, and erotic photographs, but his harem images are also family photographs that document his intimate relationships — a point scholars often gloss over or dismiss entirely. [6] Yet discussing the shah’s photographs is a springboard for how these types of images would later become more representative of a bourgeois, nuclear family during the Pahlavi Dynasty of the twentieth century. The bridge or transition from the harem family photograph to the nuclear one could be found in the case study of family photographs of the shah’s daughter ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family.

I would suggest three particular phenomena as possible forces in shaping the family photography of the Qajar elites who engaged with the practice more frequently than did the average person.[7] First, several noble circles were preoccupied with the writings of The Education of Women (1304 hijri/1886) and The Vices of Men (1312 hijri/1894), which debated the obedience of wives versus the demands for an equal, loving marriage between a woman and a man, thus making men more responsible for the happiness and emotional and sexual satisfaction of their wives. Second, the harem was dissolved as a state institution under ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s brother Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1896–1907). And third, nationalist discourses were developing in the late nineteenth century that placed more importance on women as mothers who raised healthy, patriotic citizens, and eventually these discourses would frame Iran itself allegorically as a motherland during the Constitutional Revolution (1905–11). ʿEsmat al-Dowleh would have been quite aware of all these developments, as she was a Qajar princess, highly educated, in touch with many intellectual circles in Tehran, and cognizant of the criticisms and issues plaguing her brother’s reign — directly inherited from their father. In this regard, one cannot argue solely that the personal photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family (taken in the family studio or by her husband, Doost Mohammad) blindly mimicked the signs of the times (although ideology works in such a latent fashion), but certainly ʿEsmat al-Dowleh was tuned into the cultural-political shifts in her country, and so was her husband, who had lived abroad for several years and frequented intellectual circles outside Iran.

I

Before looking more into ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s family photographs, I would like to explore some scholarly definitions of family photography as a genre. Julia Hirsch begins Family Photographs (1981) with a simple definition that the family photograph contains more than one person, and those individuals demonstrate some similar physical feature to connote a bloodline.[8] Hirsh’s text then becomes more nuanced as it invites the reader to ruminate on the concept of the family photograph and the types of relationships it depicts. The keyword is relationship, and how related individuals express family ties in photographs with particular objects, gestures, and poses. Hudgins includes the spatio-temporal quality of these relationships depicted in family photographs, as well as the images’ ability to create belonging and a sense of individuality among the people portrayed.[9] Relying on Bourdieu, the family photograph is also one that portrays intimate power and economic relations and relays these messages both inside and outside the familial structure, which is deceptively porous.[10] Furthermore, family photographs, even if they are snapshots, are not taken willy-nilly. As non-state-institutionalized as they are thought to be — private photographs taken within intimate spaces — they are also “rule-governed” and engaged in a “socially patterned communicative process,” however unspoken, thus still constituting a social institution.[11] Whether this is intended, family photographs both follow and depict social norms, myths, and expectations by appropriating the motifs, aesthetics, props, and poses seen in earlier images although there are changes, variations, and interpretations.[12] In this way, family photography, despite its prolific presence in photo history with many different photographers and sitters, is actually very conservative and does not often deviate from the social script indoctrinated by state apparatuses.[13]

These definitions are perhaps complicated by the newness of photography in the nineteenth century; however, Lalvani argues,

Central to the ideological construction of the family was the practice of bourgeois portraiture, and its representations played a significant part in affirming a set of social relations and a mode of subjectivity integral to the operations of that ideology. On one hand, the many photographs that we encounter of the middle-class family appear unremarkable because of their unrelieved consistency of pose, expression, and general format. On the other hand, their lack of aesthetic values speaks to the presence of ideological conventions at work which reductively abstract from multiple families a singular and powerfully informing representational type. Moreover, the apparent innocence with which they offer themselves to the eye disappears once these photographs are located in the context of the discourses of the family, within whose ideological field the density of their meaning is disclosed.[14]

The family photography as described in scholarly literature has relied mainly on a bourgeois concept of the nuclear family in Eurocentric fashion. This “innocence” that Lalvani speaks of is not just bourgeois indoctrination subtly hidden in nineteenth-century family photographs but also the inherent Eurocentrism in reading and identifying which characteristics qualify an image as a family photograph, for example, excluding harem photographs and even polygamy in general. Furthermore, in addressing Qajar photographs that depict love and romance, Mohammadi Nameghi and Pérez González argue that these types of photographs were part of a cultural transformation that would develop the “family photograph” to comprise mothers, fathers, and their offspring, implying that the initial nineteenth-century family photographs of only men and their children (discussed below) act as “proto-family photographs” until women are readily seen.[15] This sort of predication of the modern nuclear family defined by capitalist apparatuses privileges the types of family photographs taken under Reza Shah that helped to create a semblance of a modern, industrialized nation and to designate sitters as “kingly citizens.” In truth, the modernization and the globalization of family values shifted during the Qajar Dynasty, while the older Qajar values of the family still lingered under Reza Shah, who himself had two wives.

II

Fig. 1. Abdallah Khan, Fath Ali Shah enthroned with his sons, attended by 'ghulams,' 1816-20, watercolour, Add.Or.1239, © The British Library Board.

Fig. 1. Abdallah Khan, Fath Ali Shah enthroned with his sons, attended by 'ghulams,' 1816-20, watercolour, Add.Or.1239, © The British Library Board.In tracing the history of the Qajar family photograph, lineage began and ended with men in terms of visual depictions despite the requirement that the crown prince be born of a Qajar mother. Iranian portrait painting played a major role in recording this lineage before the advent of the photograph. For example, in the paintings of the second Qajar king Fath-ʿAli Shah (r. 1797–1834), who was renowned for the number of his progeny (at least 260 children),[16] princes were depicted (sometimes with the shah himself) as a way to proclaim Fath-ʿAli Shah’s legitimacy and power as a ruler by virtue of his virile prowess (figure 1).[17] The depictions of princes were indications that the shah was a great ruler, but they also consolidated the Qajar claim to the throne, especially in light of his eunuch uncle Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar (r. 1789–97), who still had a harem but could not produce children.

As demonstrated by these precursors of photography in Qajar painting, whatever enters visual culture satisfies or supports ideological roles and sociological functions. The fact that both photography and the genre of the family photograph immediately developed a strong foothold in Qajar Iran as a remediated form of painting points to social needs that the family photograph fulfilled, in particular those of the dominant class. When sociologist Bourdieu writes of postwar, twentieth-century France, he tells us that family photographs, especially ones of children, reaffirm the construction and division of labor of the typical bourgeois family.[18] If photography did not possess such a concrete purpose and capability to legitimize bourgeois class aims, then it would not have been utilized in the first place. On the contrary, the French upper classes used photography in more artistic, aesthetic ways in consolidating their class standing — the fact that they could use photography in loftier ways also indicates an affirmation of class goals and aims. Although Qajar Iran cannot be compared to postwar France in terms of both time and place, Bourdieu’s analyses of photography as a way to demonstrate and to legitimize class goals illuminates why family photography was adopted so quickly by the elite classes in Qajar Iran: there was already a strong presence of family portraits in painting and the need to affirm the power, progeny, and the rightfulness of the Qajar throne, especially after the political instability of the eighteenth century and the continual contestations during the dynasty, such as an attempt on Nasir al-Din Shah’s life in 1852 and his assassination in 1896 by Mirza Reza Kermani (1847–96).

Following the arrival of photography in Qajar Iran (which could have been as early as 1839 — the year the daguerreotype was announced in Paris),[19] there are many extant family photographs that depict men with their children without the mother(s), much like the earlier royal Qajar paintings (figure 2).[20] Sometimes a mother is featured, but she is fully veiled and not integral to the composition (figure 3). This phenomenon occurred for several reasons. For instance, the sexual prowess of the men depicted pointed to a sort of virtue, and his children were proof of that virility. Children themselves were a desired goal in any marriage. But in some cases, if a man had children with multiple wives, this made for an awkward image (and in fact the women were unnecessary to the message when a man already had the prize — the offspring indexed the women). Women (including daughters after age nine and other female relatives) also provided a sense of namus (honor) for husbands and other male relatives, so to have wives on display (be there one or many) without hijab in front of the camera or in the studio of a male photographer proved problematic, as not everyone would be or should be privy to seeing the face of another man’s wife (or wives). As she was the family’s honor, it was an honor for only a select few to see her unveiled. Finally, there were some studios in the nineteenth century that did not allow entrance to female sitters.[21] It was later in the nineteenth century that photography studios were setup specifically for women with women photographers.[22]

With the idea of namus in mind, Nasir al-Din Shah’s many photographs of his wives provide the viewer with another story that may not correlate with photographic practices on the ground as mentioned above, although photographic traditions varied from city to city. The shah, as well as his assistants, took many photographs of his harem wives, which were meant to be private so that namus would be protected, but there were times that these images were not under lock and key.[23] Moreover, the protocols of the elites did not always mirror the expectations of mainstream society. For example, in 1844, the shah’s only full sister, ʿEzzat al-Dowleh (1834–1905), had her picture taken by the French photographer Jules Richard (Richard Khan, 1816–91), who was then invited by other Qajar nobles to photograph their families, including other elite women.[24]

Fig. 4. Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, Nasir al-Din Shah in his inner quarters, c.1860, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ب 195-180), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A58.html.

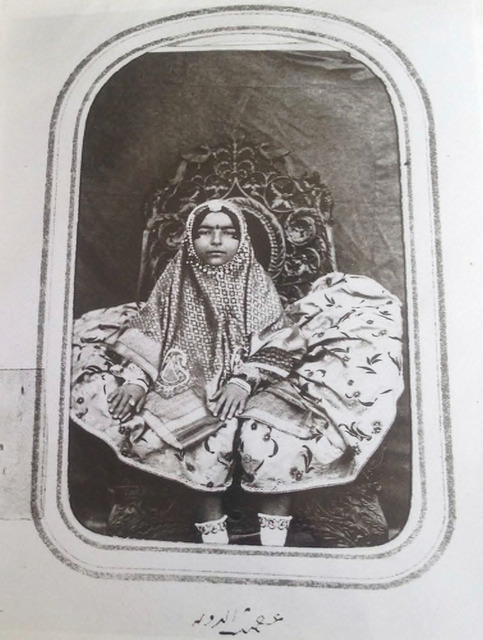

Fig. 4. Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, Nasir al-Din Shah in his inner quarters, c.1860, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ب 195-180), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A58.html. Fig. 5. Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, ND, albumen print, Album 362.4, #2, Golestan Palace Archives, Tehran.

Fig. 5. Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, ND, albumen print, Album 362.4, #2, Golestan Palace Archives, Tehran.It is notable that Nasir al-Din Shah not only took pictures of his wives but also made self-portraits with them and took photographs of his wives posed with the children (figure 4).[25] Yet photographs of Nasir al-Din Shah as a father with his own children are not so common, which provides another example of nobles sometimes behaving differently from what was the norm in the mainstream culture. He may have not posed often with his children, but he took several pictures of his daughters, among them ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, who is shown here as a child (figure 5). His daughters in their youth were portrayed just as much as were his sons, if not more (based on extant, available photographs). ʿEsmat al-Dowleh would grow up with the camera, become accustomed to being around photography, learn the art form, and later establish a very prominent photography studio in her home with her husband, Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek.

What is complementary is that Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek also posed in many photographs as a child and sat with his own parents together as a nuclear family even though his father, Doost ʿAli Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (Nezam al-Dowleh, 1820–1873), had children with another woman, Khadijeh Khanom. Khosronejad suggests that the family most likely had cameras in the house and perhaps experimented with them, thus instilling the love of photography in Doost Mohammad at a very early age, much like the upbringing of his wife.[26] In a private family photograph album of the Moayeri family, several images show a triad of Doost Mohammad with his mother, Mah Nesaʾ Khanom (d. 1875), and his father.[27] One of them was taken in the 1860s, presumably just before Doost Mohammad married ʿEsmat al-Dowleh. All three family members gaze in different directions, but the father, standing in the middle, bridges the group by touching the shoulders of his wife and son. Mah Nesaʾ Khanom takes the sitting position as the one accorded the most deference and is stunning in regal attire with her face made up and with emphasized eyebrows in accordance with the fashion of the time. The two males, who are more in profile, are also dressed in the finest fashion. The family shows itself not only as wealthy, royal, and sophisticated (worthy enough to marry off their son to one of the king’s daughters), but also close-knit and bonded through the gestures of the patriarch.

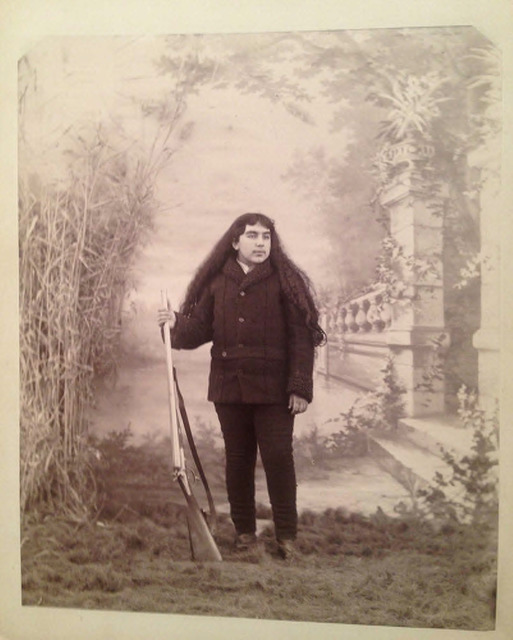

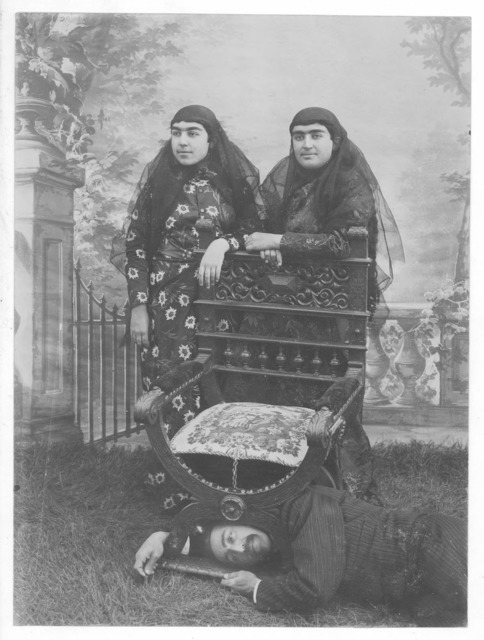

As the couple grew up with photography prominently in the household, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh was mindful of its political power and its ability to shape identities and ideologies, as well as to construct fantasies and alternate selves. In 1899, she recorded a message on a phonograph: “If I were to describe all the inventions of this [modern] period, it would take too long. . . . Consider that once we [Iran] were more powerful than all of our neighboring governments and our authority surprised and astonished all foreigners. But now it has come to pass that we are astonished by their inventions and industry. We have been around since the ancient times, but they [Europeans] are new; we must discover the reasons and the causes of this.”[28] The philosophical underpinnings of this message reveal not just the general “astonishment” of Iranians of these inventions,[29] such as the camera, cinema, and the gramophone, but also their associations with governments and their agendas, which were indications of the hegemonies of the geopolitical entities that had spread and disseminated these inventions. This demonstration of photography as a machine full of potential and make-believe manifests in the private photographs of her family posing playfully in front of the camera, such as her daughters, ʿEsmat al-Moluk (b. 1874) and Fakhr al-Taj (b. 1879), masquerading as men, which has become a photographic trope in a pre-Constitutional Revolution context (figures 6 and 7).

Fig. 6. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (and ʿEsmat al-Dowleh?), ʿEsmat al-Molouk dressed as a man, c.1890s, repository unknown, found in this article although the identification is incorrect: http://cafetarikh.com/News-19478/%DA%98%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B1%DA%A9-%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%B2%DB%8C—-%D8%B9%DA%A9%D8%B3/?id=19478.

Fig. 6. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (and ʿEsmat al-Dowleh?), ʿEsmat al-Molouk dressed as a man, c.1890s, repository unknown, found in this article although the identification is incorrect: http://cafetarikh.com/News-19478/%DA%98%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B1%DA%A9-%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%B2%DB%8C—-%D8%B9%DA%A9%D8%B3/?id=19478. Fig. 7. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (and ʿEsmat al-Dowleh?), Fakhr al-Taj dressed as a man, c.1890s, courtesy of the Kimia Foundation.

Fig. 7. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (and ʿEsmat al-Dowleh?), Fakhr al-Taj dressed as a man, c.1890s, courtesy of the Kimia Foundation.What is striking about the photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family, in addition to the variety of role-play, is that they are some of the earliest Qajar examples of the constructed image of a loving, nuclear family, which also a form of role-play. Certainly, the photographs of Nasir al-Din Shah’s harem show at times playfulness and the shah’s love for his family, and there have been other Qajar photographs that show couples who are affectionate, as well as the semblance of a stable nuclear family (figure 8). Yet the narrative of a happy, devoted nuclear family was a staple and even a developed genre through the photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her immediate family. In fact, before “the termination of the harem as an institution” during the reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah,[30] the photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family are decidedly un-harem-like or even anti-harem.

III

Fig. 8. Anonymous, Untitled, ND (late nineteenth-/early twentieth century), courtesy of Mehrdad Nadjmabadi.

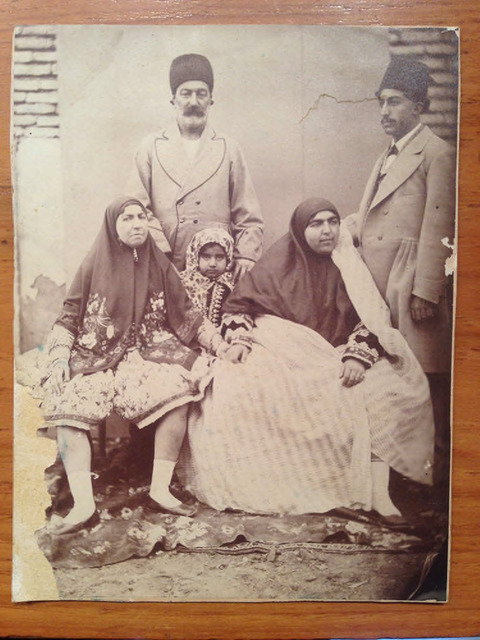

Fig. 8. Anonymous, Untitled, ND (late nineteenth-/early twentieth century), courtesy of Mehrdad Nadjmabadi. Fig. 9. Anonymous, Group Portrait with ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (on the right), ʿEsmat al-Molouk in the middle, and Taj al-Dowleh (the mother of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh) on the left, late 1870s, courtesy of the Kimia Foundation.

Fig. 9. Anonymous, Group Portrait with ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (on the right), ʿEsmat al-Molouk in the middle, and Taj al-Dowleh (the mother of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh) on the left, late 1870s, courtesy of the Kimia Foundation.ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek married when they were both around ten years old, in 1283 hijri (1866 CE).[31] According to Carla Serena, they became known as one of the happiest couples in Tehran[32] and produced four children (two daughters and two sons).[33] Sometime after his daughter Fakhr al-Taj was born in 1879, Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek traveled to Karbala and married another woman, Asafa Khanom, the daughter of the man who was in charge of his father’s assets, which he successfully obtained, and then divorced her.[34] Soon thereafter, he traveled to Paris, living there for three years (1882–85). Based on several inscribed cartes -de-visite given to Doost Mohammad by female friends, it is speculated that he could have had love affairs with various women.[35] While in Paris, he learned the art of photography but also squandered his father’s inheritance, which led him to ask the ever-loyal ʿEsmat al-Dowleh for additional financial support.[36] Eventually, Nasir al-Din Shah intervened. Viewing the situation as disrespectful to his daughter, he forced the prodigal son-in-law to return to Tehran and to his wife.[37]

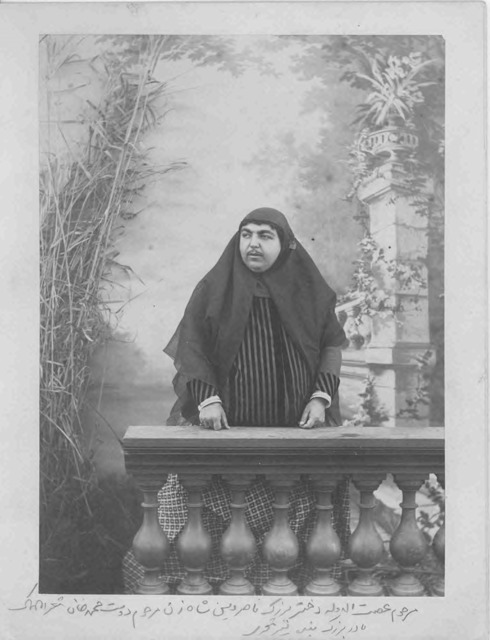

Although there are many photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, mostly taken by her husband, there are not that many that I know of her posing directly with him. In one photograph, however, she leans in closely toward her husband while his hand touches the back of her chair (figure 9). He averts his gaze from his wife, respecting her presence; however, it was a common strategy for the sitters to strike different poses and sometimes look in different directions in order to distinguish them, much as Hudgins suggests. Furthermore, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh holds the hand of her mother, Taj al-Dowleh. Again, the most respected subjects are seated, so the photograph clearly privileges the sitting ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her mother as part of the royal family while her husband stands beside her. Despite the scarcity of existing photographs of the couple together, Doost Mohammad had his wife pose in front of the camera often, and they worked together in the studio that was in their home: “ʿEsmat al-Dowleh had been an assistant to her own husband Doostmohammad Khan in photographic work, the gathering of rare [photographic?] copies, and tableaux”[38] (figures 10 and 11). Here, Banafsheh Hejazi implies that ʿEsmat al-Dowleh was involved in the actual production of Doost Mohammad’s photographs even if she was also in front of the camera’s lens. In their photographs, her poses are often full-bodied so that her voluptuous curves are displayed, accentuated by her best clothes. Her makeup is applied, and her hair is styled to perfection, according to the beauty standards of the time. Thus, the images of her speak to her elegance and royal status, always showing her as an attractive, desirable, refined noblewoman.

Fig. 10. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5216), http://iichs.org/index.asp?id=1582&doc_cat=9.

Fig. 10. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5216), http://iichs.org/index.asp?id=1582&doc_cat=9. Fig. 11. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5234), http://iichs.org/index.asp?id=1582&doc_cat=9.

Fig. 11. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5234), http://iichs.org/index.asp?id=1582&doc_cat=9. Fig. 12. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (?), Fakhr al-Taj and Her Father Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayer al-Mamalek, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran.

Fig. 12. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (?), Fakhr al-Taj and Her Father Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayer al-Mamalek, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran. Fig. 13. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (?), ʿEsmat al-Moluk (left), Fakhr al-Taj (right), and Their Father Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayer al-Mamalek, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran ( ع 3-5222), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A43.html.

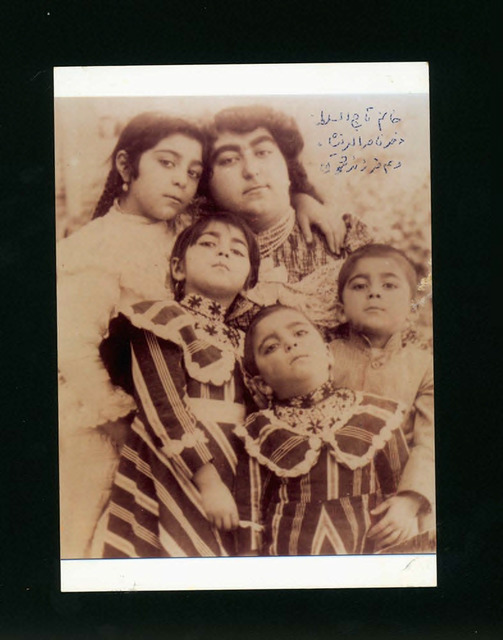

Fig. 13. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (?), ʿEsmat al-Moluk (left), Fakhr al-Taj (right), and Their Father Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayer al-Mamalek, ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran ( ع 3-5222), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A43.html.Like the other men of his time, Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek also posed with his children without his wife, sometimes playfully. For example, he places his head under a chair behind which his daughters stand (figures 12 and 13). Often, the photographs of men with their children were not exactly about fatherly love and the bond with their children, but rather about documentation, lineage, enforcing patriarchy, and sexual prowess, all of which reflected both the familial and the social duties as men of the family. This is not to say the depicted men did not love their children, but to represent themselves with their children upheld ideological and social functions that further integrated them into Qajar society and its norms and expectations. But what is powerful about the photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family is that in addition to her husband posing with their children, she posed frequently with her mother and daughters, and her sister, Taj al-Saltaneh (1883–1936), also posed alone with her children (figures 14 and 15). As Qajar princesses, these women legitimized their family lines more so than did their husbands. Of course, other Iranian women had posed with their children before them, so they did not accomplish something out of the ordinary, but these images of Qajar princesses exhibit a motherly love and bond that were not seen as often as were men posing with their children.

Fig. 14. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?), ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (right), ʿEsmat al-Moluk (middle), and Fakhr al-Taj (left, sleeping), ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran (ع 3-5378).

Fig. 14. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?), ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (right), ʿEsmat al-Moluk (middle), and Fakhr al-Taj (left, sleeping), ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran (ع 3-5378). Fig. 15. Anonymous, Taj al-Saltanah and Her Children, ND, 15x11 cm, Taj Iran Zarghami Fasihi Collection, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/15155A8.html.

Fig. 15. Anonymous, Taj al-Saltanah and Her Children, ND, 15x11 cm, Taj Iran Zarghami Fasihi Collection, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/15155A8.html.In several photographs, particularly when her daughters are older, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh gestures very lovingly to them in ways not really seen before in Qajar photography, not even in the playful photographs of her father, Nasir al-Din Shah. All photographs are representations, so they should not be taken as literal, empirical evidence, but certainly ʿEsmat al-Dowleh wanted to send a message about her relationships with her children and herself as a devoted mother. In fact, she is almost always posed as the one giving affection to her daughters. In one photograph, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh lays her head in her daughter’s lap while stripping bamboo. Meanwhile, Fakhr al-Taj leans in over her mother, smiling at the camera (figure 16). In another photograph, of the mother and daughter by a stream, possibly montaged by Doost Mohammad (who was skilled in this technique), ʿEsmat al-Dowleh reclines and touches the water with an outstretched hand. Fakhr al-Taj rests her head on her mother’s hip, again engaging the camera (figure 17). These are reminiscent of the images of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh posed with her own mother Taj al-Dowleh, in which they are often shown touching each other in tender ways (see again figure 9).

Fig. 16. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (left) and Fakhr al-Taj (right), ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran (ع 3-5259), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261B36.html.

Fig. 16. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (left) and Fakhr al-Taj (right), ND, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran (ع 3-5259), http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261B36.html. Fig. 17. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (right) and Fakhr al-Taj (left), ND, repository unknown, found in this article although the identification is incorrect: https://radiokoocheh.com/article/140895.

Fig. 17. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Dowleh (right) and Fakhr al-Taj (left), ND, repository unknown, found in this article although the identification is incorrect: https://radiokoocheh.com/article/140895.IV

During the late nineteenth century, attitudes toward the family, motherhood, and parental bonds were changing, in particular notions of the importance of motherhood and romantic love, as demonstrated by both the writings and the propaganda of the time. Many of these ideas of the family developed through various forms of global contact: foreigners in Iran, such as politicians, missionaries, and doctors; Iranian elites and reformers abroad, such as Mirza Malkom Khan (1833–1908); access to published materials entering Iran, such as the writings of Rousseau; and modern institutions, such as the polytechnic Dar al-Fonun (est. 1851). One outcome of these developments was the motif of Iran as a mother or motherland, and patriotic women were called madaran-e vatani[39] (matriots) in political discourse during the Constitutional Revolution (1905–11). Although ʿEsmat al-Dowleh had passed away by 1905, and her daughter Fakhr al-Taj went into exile in Odessa with ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s brother Mohammad ʿAli Shah Qajar (r. 1907–09) after he was deposed, there was a percolating discourse of motherhood long before 1905 that at least the elites would have been privy to. Kashani-Sabet makes the connection between an emphasis on monogamy, a happy family, and the importance of mothers and the growing concerns of both hygiene and venereal disease, especially syphilis, which carried a death sentence until its penicillin “magic-bullet” cure in 1910, hence not only disseminating an ideology of “motherhood, child care, and maternal well-being,” but also connecting these priorities to nationalist concerns, such as procreation should lead to the production of healthy citizens in the later Qajar and Pahlavi Dynasties.[40] These discussions of love, marriage, children, and hygiene were made manifest in Qajar society during ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s time via journals, such as Akhtar and Ettelaʿat, and manuals on hygiene by doctors, both Iranian and foreign, such as Abu al-Hasan Khan Tafreshi (1845–1906), physician and director of the State Hospital in Tehran.[41]

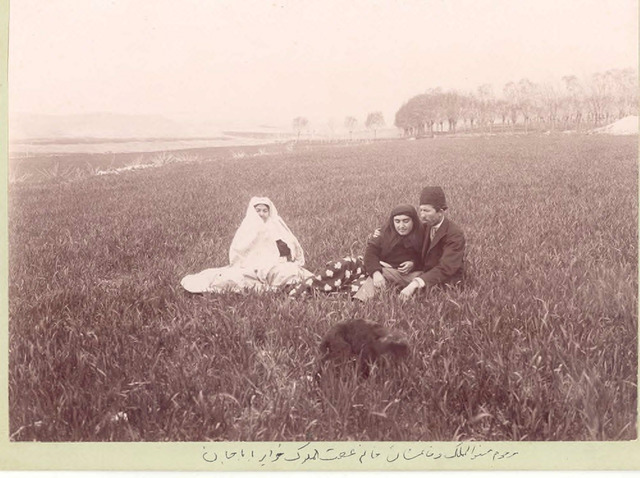

In terms of romantic images, many were produced during the Qajar Dynasty, in paintings and in other genres. There were literary prototypes of couples or legendary figures, such as Shirin and Khosrow from the national epic Shahnameh (Book of Kings, c. 1010), and ideal, heterosexual romantic couples, a staple in Iranian painting long before the Qajar period.[42] Yet the image of a known husband and wife posing sweetly together for a portrait was neither typical nor common, underscoring how photographs of romantic couples in Qajar photography were an innovative form of visual culture. In one very tender image from the early 1890s, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s daughter ʿEsmat al-Moluk and her husband, Hassan al-Mamalek (Mostowfi al-Mamalek, 1875–1932), sit together outside, but they are chaperoned by an older woman (figure 18). ʿEsmat al-Moluk reclines and leans into her husband’s chest. Both her hands rest on his leg, while his arm drapes around her. It is not clear who the photographer was, but most likely ʿEsmat al-Moluk’s father, Doost Mohammad, at whom the older woman stares. In another shot of the same scene, the couple cuddle as ʿEsmat al-Moluk pets a goat in her lap (figure 19). In both images, the couple seem very comfortable showing affection in front of the camera — the photograph, however representational, does suggest an actual loving couple within its framing, which was still not all that common in late-nineteenth-century Iran.

Mostowfi al-Mamalek was known to be an honest, upstanding politician, serving faithfully under both the Qajars and the Pahlavis.[43] These early romantic photographs of him and his wife complement his political reputation and thus show a changing tide of romantic love and companionate marriage and their connections to state ideologies in twentieth-century Iran. Some fifteen years after these photographs were made, however, Mostowfi al-Mamalek began to take multiple wives; hence, the photograph as a moment in time illustrates only one narrative among many and cannot be fully trusted to tell the whole tale.[44]

Fig. 18. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Moluk and Hassan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, early 1890s, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A218.html.

Fig. 18. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Moluk and Hassan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, early 1890s, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A218.html. Fig. 19. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Moluk and Hassan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, early 1890s, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A219.html.

Fig. 19. Amir Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek (?),ʿEsmat al-Moluk and Hassan Mostowfi al-Mamalek, early 1890s, Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran, http://www.qajarwomen.org/en/items/1261A219.html.By the late nineteenth century, marriages that promoted romantic love and spouses caring for each other intimately, as opposed to ratifying a contract through copulation and procreation, were definitely on the minds of many Qajar elites. For example, in 1886, a small treatise by an anonymous writer entitled Taʾdib al-Nesvan (The Education of Women) was read widely among the nobles in Tehran, sparking debates about how women should comport themselves.[45] Some of the chapters call for women not complain, to watch what they say to their husbands, and not to sulk. Encouraged by the educated circles of women in Tehran, Bibi Khanom Astarabadi (1858–1921) wrote a response to The Education of Women called Maʿayeb al-rejal (The Vices of Men). In the introduction, Bibi Khanom agrees that women should respect their husbands and be kind to them, but with this caveat: only if the husbands return the favor:

[M]y sisters in religion, you should fulfill all these admonitions provided the husband be faithful, fears God, avoids sin, and behaves kindly and well toward his wife. He should not ask her something that cannot be done, and he should not find fault and quibble with you. He should not be ruthless and cruel; he should also not be stubborn and always with his friends and a truant from home; he should not womanize and be loving boys or, like a spineless husband, divorce his wife without any reason. If the husband has any of these traits, then, of course, it is much better that you get rid of him as soon as possible while you are young and not burdened with sons and daughters.[46]

Bibi Khanom then lists some of the vices of men that make them unfit husbands, such as drinking alcohol excessively, gambling, drug addiction, and debauchery. She also criticizes grown men’s sexual appetites for amrads (prepubescent boys). Najmabadi notes other writers of this era, such as Mirza Fath-ʿAli Akhundzadeh (1812–1878), Mirza Agha Khan Kermani (1854–1897), and Hassan Taqizadeh (1878–1970), who also discouraged this sexual practice of courting amrads, hoping to foster romantic love and companionate marriage as signs of a modern state.[47]

Although I am not entirely sure that ʿEsmat al-Dowleh or her family read these writers, it is likely that she read Bibi Khanom’s work; at the least, she knew of the debates surrounding what women and men should do to be successful in their marriages so that both partners find happiness. Bibi Khanom's mother, Khadijeh Khanom, known as Molla-Baji, was a governess at the Nasiri court and quite close to Shokuh al-Saltaneh, the mother of Mozaffar al-Din Shah. Later, Bibi Khanom’s brother Hossein ʿAli would become a physician to Mozaffar.[48] As a little girl, Bibi Khanom was in the Naseri harem with the other girls being instructed, and after she married, she continued to visit the harem.[49] Furthermore, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and Bibi Khanom were in the Nasiri harem at the same time, knew each other, and grew up together; thus, it is safe to assume that on some level, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh was aware of the conversations regarding gender equality in marriage and knew about these texts.

Despite the potential for ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s family photographs to illuminate changes in attitudes toward marriage and family in late-nineteenth-century Qajar Iran, there remains a conservative twist that still upheld traditional values and the ways of the nobles and elites. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh did not choose her husband — her marriage was arranged when they were both around ten years old, perpetuating the notion that love comes after marriage, and that families know what is best for their children. Even though ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and Doost Mohammad Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek overcame several crises together, they were able to cultivate at least the semblance that they had a very successful marriage, thus re-enshrining the value of arranged marriages for young people. In this sense, both the traditional and the modern could merge: Iranians in the late nineteenth century did not have to lose or change their ways or their values — they just had to approach them differently.

As a subtext, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s family photographs convey that an arranged marriage still encouraged heterosexuality and could be happy and prosperous with wonderful children. And certainly, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s family photographs demonstrate a healthiness and emotional robustness of the royal family, attempting to dispel notions that the elites were licentious and ridden with venereal disease.[50] Their photographs emphasize that they were not corrupt but rather stable, decent, loving, traditional but also modern people. The supposition derived from this self-representation was a political one as well: that the Qajars were still fit to rule Iran.

V

The shift in representation and the balance between reality and performance in family photographs of the Qajar period that this essay explores through the images of ‘Esmat al-Dowleh has another complex layer. New information has been put forward that Doost Mohammad may have sexually assaulted his daughter.[51] This claim has been supported by a reading of a family anecdote by one descendent and of suggestive photographs of Fakhr al-Taj in white undergarments presumably taken by her father.[52] The assertion must be examined with caution, as if it is confirmed, it would radically alter the legacy of Doost Mohammad.[53] It would also require another interpretive layer to ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s photographs as a phantasmagoria of a loving family to the biruni or zaher (outside world) and a record of violence (both actual and metaphorical) in the andaruni or baten (inside, private world). Scholars have pointed out that the modern practice of family photography, which tends to be dominated by happy scenes, erases or overshadows negative emotions and violence. The intersection of gender-based violence and family photography is a topic that requires considerable exploration beyond the scope of this essay. But one can acknowledge, from a cursory glance, that family photography can be a form of oppression to women and children, whose presence usually defines the domestic sphere where family pain and suffering reside in secret, away from the more public space in front of the camera lens, which is often controlled by the male head of the household.[54] One reading, in light of this suggestion put forward, is that the family photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh are images of devotion, emphasizing love, moral rectitude, and duty, precisely because these qualities were missing from the dynamic within the home. It is possible that family photographs hide more than they reveal. And what they do reveal is at the level of ideology, not intimacy. In this way, there is not much difference between official state photography and the seemingly more intimate aesthetics of the family photograph.

As Roland Barthes points out, the family photograph carries different meanings to those related as opposed to those who are not,[55] and Marianne Hirsch elaborates that the photograph changes with the generational divide, creating post-memories for those who come after.[56] Because family photographs are ultimately about human relationships, they resonate with viewers and empathically, if only on an unconscious level. The harem photographs of Nasir al-Din Shah are family photographs, but because the harem as a state institution of power no longer exists in the modern world, few, if anyone, can relate to these photographs. In this regard, the images of the shah’s harem become polysemic by way of the various lenses from which one views them; they are not ideologically “normalized” as modern family photographs, as shaped discursively during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The family image has always been a staple of Iranian photographic practice. But, as demonstrated in this essay, photographs from the Qajar era show visually how attitudes about the family shifted and changed throughout its long durée, as seen in the photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh and her family. This change resulted in firmly establishing a new way to represent domesticity during the Pahlavi Dynasty — that is, in the form of the nuclear, heterosexual family photograph. The photographs of ʿEsmat al-Dowleh record the sorts of concerns and conversations taking place in real time, whether she and her family actively played out those debates and discussions among the Qajar elites or were influenced by them such that their behaviors became naturalized through prevailing ideologies. It is these family photographs that resonate with a modern viewer, thus signifying the death or change of the older ways of life. ʿEsmat al-Dowleh’s photographs become some of the first in Iran that a later globalized audience could “relate” to in that her images do not have to be relegated as historical or anthropological (and hence “other”) but are somewhat similar to the ones in our own albums and, indeed, in our smartphones.

Acknowledgments

I extend much gratitude and appreciation to Houman Sarshar and Mehrdad Nadjmabadi, both of whom have supported my research with friendship and collegiality. I would also like to thank Donna Stein, Elmar Seibel, Fariba Taghavi, and Jasamin Rostam-Kolayi for their enlightened comments and encouragement. Thank you.

Staci Gem Scheiwiller is Associate Professor of Modern Art History at California State University, Stanislaus. Her most recent publications include Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography: Desirous Bodies (Routledge, 2017), an edited volume with Markus Ritter entitled The Indigenous Lens: Early Photography in the Near and Middle East (De Gruyter, 2017), and an earlier edited volume, Performing the Iranian State: Visual Culture and Representations of Iranian Identity (Anthem Press, 2013).

Reza Sheikh, “The Rise of the Kingly Citizen: Iranian Portrait Photography, 1850–1950,” in Portrait Photographs from Isfahan: Faces in Transition, 1920–1950, ed. Parisa Damandan (London: Saqi, 2004), 231–53.

Mohammad Khodadadi Motarjemzadeh, “Photography in the Grey Years (1920–40)” in History of Photography 37, no. 1 (February 2013): 118–19.

For examples of photographs, see Parisa Damandan, ed., Portrait Photographs from Isfahan.

See Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 131–50.

The scope of this article precludes addressing why elites patronized photography more than did average people on the street. For a longer explanation, see Staci Gem Scheiwiller, Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography: Desirous Bodies (New York: Routledge, 2017), 130.

Julia Hirsh, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning, and Effect (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 3.

Nicole Hudgins, “A Historical Approach to Family Photography: Class and Individuality in Manchester and Lille, 1850–1914,” in Journal of Social History 43, no. 3 (Spring 2010): 564.

See Pierre Bourdieu, et al., Photography: A Middle-Brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990).

Christopher Musello, “Studying the Home Mode: An Exploration of Family Photography and Visual Communication,” in Studies in Visual Communication 6, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 23, 28.

Louis Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (London: NLB, 1971), 136–37, 146.

Suren Lalvani, Photography, Vision, and the Production of Modern Bodies (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 55–56.

Khadijeh Mohammadi Nameghi and Carmen Pérez González, “From Sitters to Photographers: Women in Photography from the Qajar Era to the 1930s,” in History of Photography 37, no. 1 (February 2013): 68.

Abbas Amanat, “Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah Qājār,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, IX/4, 407–21; available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/fath-ali-shah-qajar-2 (accessed online 17 June 2018).

Scheiwiller, Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography, 166–67.

It is possible that Shahzadeh Malek-Qasem Mirza, b. Fath-ʿAli Shah (1222-c. 80/1807-c. 62), was the first Iranian photographer, as he had read La Revue des Deux-Mondes and Charivari in 1839, and a camera was listed in his inheritance. Chahryar Adle and Yahya Zoka, “Notes et documents sur la photographie Iranienne et son histoire: Les premiers daguerréotypistes [Notes and Documents on Iranian Photography and Its History],” in Studia Iranica 12 (1983): 262, 270–71; Kianoosh Kiani Haftlang, Ganjineh-yeh ʿaksha-yeh tarikhi (Tehran: National Library and Archives of Islamic Republic of Iran, 2007), 18–19.

For more on this subject, see Ali Behdad, “Royal Portrait Photography in Iran: Constructions of Masculinity, Representations of Power,” in Ars Orientalis 43 (2013): 41–42.

Mohammadi Nameghi and Pérez González, “From Sitters to Photographers,” 48, 62.

Jaʿfar Shahri, Tarikh-e ejtemaʿi-e Tehran dar qarn-e sizdahom: Zendagi, kasb va kar [Social History of Tehran in the Thirteenth Century], vol. 3 (Tehran: Muʾassaseh-yeh Khadamat-e Farhangi-e Rasa, 1378/1999), 175–76. See also Carmen Pérez González, Local Portraiture: Through the Lens of the 19th-century Iranian Photographers (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012), 175.

Mohammad Sattari and Khadijeh Mohammadi Nameghi, “The Photography Studio of the Naseri Harem in Nineteenth-Century Iran,” in The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East, eds. Markus Ritter and Staci Gem Scheiwiller (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 282.

Shireen Mahdavi, “RISHĀR KHAN,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2016, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rishar-khan (accessed on 19 June 2018); and Khosrow Moʿtazed and Abolqasem Tafazzoli, Az Forough al-Saltaneh ta Anis al-Dowleh: Zanan-e haramsara-yeh Nasir al-Din Shah (repr. 1389; Tehran: Intesharat-e Golriz, 1377), 411.

Despite the once private nature of Nasir al-Din Shah’s harem photographs, they are available for the public and copyright usage through the state archives of the Golestan Palace in Tehran. Because the shah himself was the state and absolute ruler, so were the photographs he took, as well as those that pertained to his personal life. Although in the nineteenth century, it would have been taboo to duplicate such intimate photographs, the dissolution of the harem as a state institution in the early twentieth century eroded the notion of the harem space as being sacrosanct. In addition, the notion of the Muslim Iranian woman as a sitter to be viewed in photographs shifted from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first — from the avant-garde efforts of the Qajar elites to the practices of the average person during the Pahlavi Dynasty — that viewing the shah’s wives is not a concern of the Islamic Republic or that the state has a duty to protect the names of kings long ago. For more on this transition, see Mohammadi Nameghi and Pérez González, “From Sitters to Photographers”; and Sattari and Mohammadi Nameghi, “The Photography Studio of the Naseri Harem in Nineteenth-Century Iran.”

Pedram Khosronejad, “Two Photograph Albums from the Moayeri Family,” in Anthropology of the Contemporary Middle East and Central Eurasia 4, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 76.

ʿEsmat al-Dowleh, phonograph recording, 28 January 1899/16 Ramadan 1316, in Sasan Sepanta, Tarikh-e Tahavvol-e Zabt-e Musiqi dar Iran (Tehran: Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts, 1388), 327. I have stayed with Hamid Naficy’s translation of the passage, but he uses a different, older edition. See Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897–1941 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 86–87.

Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 59.

Khadijeh Nezam Mafi, preface to Doost ʿAli Khan Moʿayyer al-Mamalek, Vaqaeh al-zaman (Khaterat-e shikarieh) (Tehran: Nashr-e Tarikh-e Iran, 1390), 8; and Fatemeh Mazi, “Fatemeh Khanom ʿEsmat al-Dowleh,” Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies, available at http://www.iichs.org/index.asp?id=1575&doc_cat=9 (accessed 18 June 2018).

Mazi, “Fatemeh Khanom ʿEsmat al-Dowleh”; and Banafsheh Hejazi, Tarikh-e Khanomha: Barrasi-e jayegah-e zan-e Irani dar asr-e Qajar [History of Women] (Tehran: Qasideh-ye Sara, 1388), 126.

Klaus Dieter Streicher, Die Männer der Ära Nāṣir: Die Erinnerungen des DūstʿAlī Ḫān Muʿayyir al-Mamālik [The Men of the Nasiri Era] (Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang, 1986), 35.

Pedram Khosronejad, “Objects of Desire: Qajar Prostitutes in Picture,” Association for Iranian Studies (AIS) 12th Biennial Conference, Irvine, CA, August 2018.

Yahya Zoka, Tarikh-e ʿakkasi va ʿakkasan-e pishgam dar Iran (Tehran: Sherkat-e Intesharat-e ‘Elmi va Farhangi, 1997), 88.

Mansoureh Ettehadieh, “The Origins and Development of the Women’s Movement in Iran, 1906–41,” in Women in Iran from 1800 to the Islamic Republic, eds. Guity Nashat and Lois Beck (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 89.

L. Richter-Bernburg, “ABU’L-ḤASAN TAFREŠĪ,” Encyclopædia Iranica, I, 313–14; an updated version is available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/abul-hasan-b-2 (accessed 31 May 2018).

In Afsaneh Najmabadi’s milestone Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), she argues that standards of beauty for both sexes and gender demarcations began to follow more methodically a gender binary closely aligned with European, heteronormative standards; however, there was already a tradition of clearly differentiated (for a twenty-first-century audience) heterosexual couples being depicted before the Qajars. What Najmabadi refers to is the displacement of the amrad in these particular paintings, not the original appearance of heterosexual couples during the Qajar period.

Salar Bakhtiar, “The Life of Mirza Hassan Khan, Mostofi Al Mamalek,” in The Iran Society Journal (2005): 11.

Soheila Einollahzadeh, “Mirza Hassan Khan Mostofialmamalek,” Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies, available at http://iichs.org/index.asp?id=593&doc_cat=7 (accessed 18 June 2018).

Hasan Javadi and Willem Floor, introduction to The Education of Women and the Vices of Men: Two Qajar Tracts, eds. and trans. Hasan Javadi and Willem Floor (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010), ix.

Bibi Khanom Astarabadi, “The Vices of Men,” in The Education of Women and the Vices of Men, 62.

Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards, 162.

Javadi and Floor, introduction to The Education of Women and the Vices of Men, xvii.

Abbas Amanat, introduction to Crowning Anguish: Memoirs of a Persian Princess from the Harem to Modernity, by Taj al-Saltana, ed. Abbas Amanat, trans. Anna Vanzan and Amin Neshati (Washington, DC: Mage Publishers, 1993), 49.

Khosronejad, “Objects of Desire: Qajar Prostitutes in Picture.”

As a feminist, I am deeply conflicted about this claim. To say that if it were not in the primary sources, then it must not be true is a typical convention of masculinist history-making, as the lives of women (and the violence against them) are often not recorded or recognized. At the same time, ʿEsmat al-Dowleh worked very closely with her husband in the studio that was in their home and seemed to have had a tender relationship with her daughters, which suggests a counternarrative to this claim. At the same time, the frequent gaps between family dynamics and the version presented in family photographs suggest there is ample room for multiple narratives to exist. For now, I include this information as another interpretive layer until more is published and available. More on this claim will be presented in Pedram Khosronejad, Unveiling the Veiled: Royal Consorts, Slaves and Prostitutes (forthcoming October 2018).

Gillian Rose, Doing Family Photography: The Domestic, the Public and the Politics of Sentiment (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 8.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 73.

Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 21–23.