Photos Unhomed: Orphan Images and Militarized Visual Kinship

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

What can be learned of photographs in the absence of a story, when the memories that bring them to life are missing from official records? What stories can be told of photos for which little, if any, context exists? These questions emerged in the course of my research on the war in Vietnam from the perspective of Vietnamese photographers. When it comes to documenting the visual narratives of the South Vietnamese, the side that in 1975 lost, archives have posed a challenge because of their fragmented and messy state. In the United States, where Vietnam serves as a sore reminder of military defeat and national humiliation, public memory remains preoccupied with American experiences, overshadowing Vietnamese experiences of this war and its aftermath.

In the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), the South Vietnamese side of the story fares no better. To my knowledge, there are no official records of the defeated Republic of Vietnam (RVN), which collapsed after the fall of Saigon, on April 30, 1975. In contrast to the proliferation of state-funded projects dedicated to memorializing communist revolutionary heroes,[2] the very existence of the Republic of Vietnam has been expunged from the public record so thoroughly that RVN army cemeteries are neglected and even vandalized, as Hu Tam Ho-Tai, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and other critics have observed.[3]

Faced with these obstacles, I looked to personal artifacts for their potential to show what official archives pointedly disavow. In doing so, I am inspired by diaspora studies critics such as Yen Le Espiritu and Christina Sharpe and others who contend that the personal — specifically, in the form of domestic images and family narratives — affords more than just an opportunity for indulgent navel-gazing.[4] Instead, in cases where histories are fragmented and even broken, the personal, and indeed the familial, provides a vital resource for critical inquiry.

Though Espiritu and Sharpe turn to their own family photographs as one resource for grappling with splintered yet still lingering connections, I am intrigued by the potential of discarded and unclaimed works, commonly known as orphan images, for pursuing this kind of inquiry. By definition, orphan images are materials whose provenance is unknown and whose hallmark, accordingly, is a seemingly irretrievable sense of loss, particularly when it comes to contextualizing information. As long as they are “orphaned,” or separated from their owners/makers, whatever stories they tell can be only partially gleaned from what remains in them. Though I do not want to overstate the significance of the “orphan” metaphor, which, when applied to film and photography denotes unknown provenance and not necessarily family, the metaphor resonates in the context of Vietnam, where, during and after the war, the state politicized the family.

Fig. 1. Heroic Mothers installation, Vietnamese Women’s Museum, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2103, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 1. Heroic Mothers installation, Vietnamese Women’s Museum, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2103, courtesy of the author.This politicization is evident not least through the Communist Party’s deployment of familial terms of address, most notably anh em (brother and sister), to symbolically unify patriots as kin. The state’s avuncular benevolence is perhaps most clearly expressed in the figure of Hồ Chí Minh — Bác (or “Uncle”) Hồ — who famously chose not to marry and have children of his own, so that, as Olga Dror has argued, he could commit wholly to nurturing “the Vietnamese national family.”[5] A similar spirit of national sacrifice that invokes and politicizes family can be seen in the current practice of venerating women whose sons died while fighting for revolution. These women are granted the distinction of “Heroic Mothers” and receive a modest stipend from the state as well as widespread recognition for their service to the nation. Photographic portraits of Heroic Mothers, in which they are posed somberly and unsmilingly in a manner fitting for altars meant for ancestor worship, are displayed in national museums (figure 1). Through this mode of display, state commemoration practices adapt, even usurp, conventional rites of piety, as seen in the prominent positioning of patrilineal ancestral portraits on family altars. As Christina Schwenkel has argued in the context of urban planning, two seemingly disparate practices harmonize, if not always seamlessly.

The imperative to commemorate state-sanctioned histories (nhớ), Schwenkel convincingly shows, has merged with rites associated with religious and traditional ceremonies (thờ). Thus, whereas Heroic Mothers are honored along with their faithful sons for their patriotism, the memory of men who fought for the RVN, the wrong side, has no place in the state’s official story of revolution, nor are those men recognized as part of the Vietnamese national family. Seldom, moreover, do they appear on family altars.

The missing and dead ARVN men, these wayward sons who have now become wandering ghosts, as anthropologist Heonik Kwon puts it, are in this way effectively disowned from the Vietnamese national family.[6] Surviving parents and siblings are encouraged to venerate fallen heroes of the revolution but are discouraged from publicly mourning their cast-off kin. In his fascinating study of the ARVN’s “ghosts,” Kwon examines how political “bifurcations” resulting from the civil war between South Vietnam and North Vietnam, which unfolded in tandem with the global Cold War, unravel the “genealogical unity” of Vietnamese communities and reveal the significance of personal rites of ancestor worship in resisting the politicized framework of a postwar national family. This unusual act of bringing together photos of the departed who once fought on opposing sides, Kwon observes, reunites divided kin within the privacy of the domestic threshold.

Viewed from this perspective, family photographs have meaning in particularly poignant ways in Vietnam, made all the more fraught by the fact that reunion may remain impossible, even after death. Not all wayward sons find their way home. I realized just how irrevocable this separation could be in the course of visiting antique shops in Ho Chi Minh City, where vintage personal photographs, many of them domestic images, are sold by the piece and in bulk. Elsewhere, I have reflected on these photographs and speculated that they got there because they were abandoned or sold by their families, for they contained evidence of counterrevolutionary allegiances.[7] Unquestionably, photographs of ARVN soldiers provided the most damning kind of evidence, as was demonstrated in my conversations with members of the South Vietnamese diaspora, who recollect destroying photographs of ARVN officers in their family, if not their entire collection of family photographs.[8] And though it is not clear who finds these ARVN artifacts appealing, there seems to be a bustling market for this intimate type of memorabilia, in which wartime images intersect with domestic quietude.

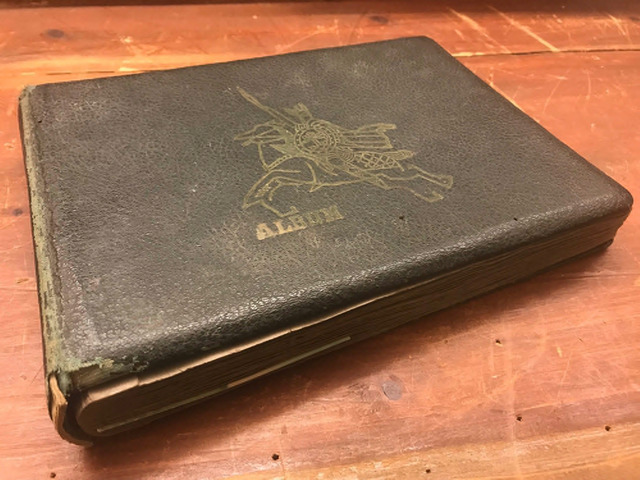

Fig. 2. Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 9.25 x 7 x 1.5 inches, green leather-bound album with gelatin silver prints mounted on paper pages, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 2. Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 9.25 x 7 x 1.5 inches, green leather-bound album with gelatin silver prints mounted on paper pages, courtesy of the author.This article reflects on how one might look at photographs when their provenance and stories have been lost, and what this loss might tell us about another side of Vietnam — what, in other words, the discourse of national family has disavowed. Here, I focus on an orphan album I found at a vintage shop during one of my trips to Vietnam several years ago (figure. 2). Although some pages are missing photos, on the whole the album, which dates to the 1950s (based on notations on the verso of many of the images), is remarkably intact, and as such, from what I could tell, rare in Vietnam, where vintage shops more commonly sell loose photographs. What makes it even rarer is its subject: What I glean from dedications and short notes scrawled on the verso of some of the portraits, is that the album’s maker was a man — I will call him Quy — who worked for the Government of the Republic of Vietnam as a member of the secret police, a position that, after the establishment of the communist state, meant he was targeted for political reeducation.

Even though I was able to establish the first name of the photographer and owner of the album, it remains an orphan object. Not only do we not know his full name, but also the very context in which I found the album, not to mention the information it discloses about inconvenient loyalties, attests to its repudiated status. I am fairly certain that the album’s owner, who was likely the chief photographer, would not want to be known if he were still alive, which is why I refer to him by a pseudonym.

Understanding the meaning of this discarded and unclaimed album, then, entails not divulging its secrets but instead keeping them, an act necessary given the state’s politicization of family during and after the war. Though its sale in the public bazaar means that anyone could have come across it, the context of online publication — which makes the contents available to a wider viewership — requires that we handle it with care and sensitivity.

In contrast to the photos of communist and ARVN men whom Kwon observes are reconciled on the ancestral altar, the wayward sons in discarded photos, such as the ones contained in Quy’s album, may never be reunited with their owner or with their families. Through a speculative exploration of the arrangement of the photos in this album, I consider how this personal artifact, through its highly gendered depiction of military trainees at work and play, might project a form of visual kinship. In making this claim, I am not asserting that this album belongs within the category of family photography, at least as this genre has been conventionally defined. Nor am I asserting that all personal albums invoke the idea of family. Rather, my aim here is more modest. I contend that this particular album, made and lost by Quy, needs to be considered within the context of the state’s politicization of family, which disavowed the very existence of ARVN men like him and most likely led to the album’s loss in the first place. When a national family has been politicized restrictively, thereby reifying a culture of memory predicated on strategic forgetting, the glimpses of fraternal affiliation provided by the album project the potential for another form of kinship: one that is visual and ultimately must confront the limits of its irrevocable estrangements.

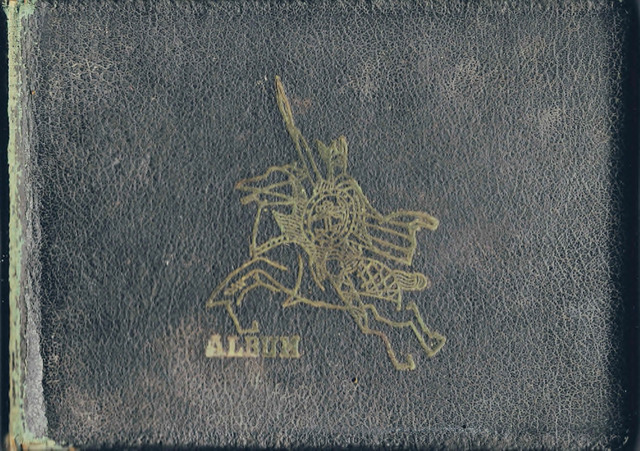

Fig. 3. Cover with crest, Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, embossed on green leather, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 3. Cover with crest, Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, embossed on green leather, courtesy of the author. Fig. 4. Military academy insignia, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 2.25 x 3 inches, watercolour on gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 4. Military academy insignia, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 2.25 x 3 inches, watercolour on gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.Fraternal Ties in the Thủ Đức Military Academy Album

The owner of the album that is now in my possession was a graduate of Thủ Đức Military Academy and went on to serve as a second lieutenant, as indicated by photos in which he poses with a banded cap that denotes his rank. Located in northeast Saigon, Thủ Đức Military Academy was established by the French in 1951. Along with Nam Định, an officer reserve training school in northern Vietnam, Thủ Đức’s mandate was to train a national Vietnamese army. Although the school in Nam Định closed after 1952, Thủ Đức Military Academy continued to operate as an ARVN training school after the Viet Minh defeated the French in 1954 and the Geneva Accords split the nation into North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the twenty-four years that it operated, the school produced an estimated forty thousand officers for the ARVN.

The album, which is bound by a loose cover of cracked leather emblazoned with a stylized knight astride his steed, memorializes the school and its legacy — above all, the fraternal community the school nurtured (figure 3). Indeed, the front inside cover of the album bears the military academy’s distinctive insignia of a blazing sword surrounded by a wreath (figure 4). These institutional markers clearly distinguish the album as a collection of school photos. It is no wonder that, as an artifact the SRV would view as betraying enemy allegiance, the album ended up in a vintage store, presumably discarded and unhomed.

Despite its orphaned status, the album retains a rich amount of information. Evocative clues appear to the attentive viewer: details in the composition, whether in pose, dress, or setting; a print’s wrinkled surface, curled edges, or torn corners; cryptic notes inscribed on the verso of images by an unknown hand; the organization of images; and the geometric imprint of faded color and adhesive residue left when an image has been torn away. Many other photos in the album, however, have been fastened onto the pages with glue, so reading them would hasten their deterioration. Viewed thus, the act of preservation, and indeed of recovery if one chooses to remove the photo, inevitably results in destruction, a paradox that Jacques Derrida calls a symptom of “archive fever.”[9]

Fig. 5. Detail of page from album showing fraternal intimacies, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, courtesy of the author.

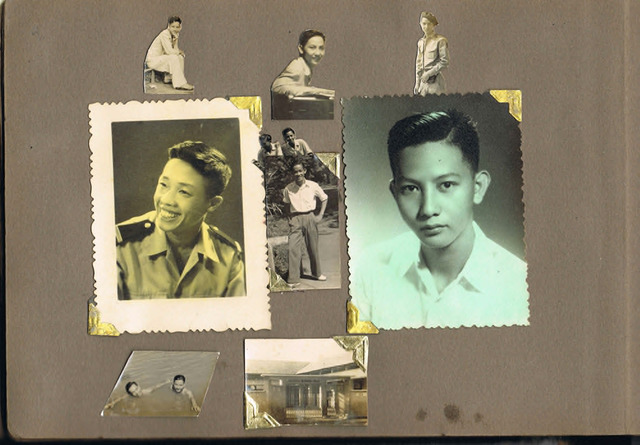

Fig. 5. Detail of page from album showing fraternal intimacies, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, courtesy of the author.The Thủ Đức Military Academy album chronicles five years of fraternal affiliation and homosocial community: most of them frange from 1951, the year the school opened, and the most recent photo is dated 1957.[10] The photographs include studio portraits, with deckled edges, of uniformed officers and snapshots of men at target practice, midstride during drills, on furlough at tourist destinations within Vietnam and abroad in Europe and the United States, and at rest, in bed, embracing in an expression of physically intimate communion, which is culturally acceptable among Vietnamese men but would be unusual to Americans (figure 5). Yet, despite Quy’s decision to forgo chronology in assembling the album, the inscriptions reveal just enough detail for a sketch of his life, from his days as a schoolboy in Saigon, to holidays in his hometown of Bạc Liêu, in the Mekong Delta, where some of his friends sometimes visited him, through his training in the military academy during critical years when the institution shifted from French to Vietnamese control, to his eventual position as department head of the Phòng Nhì, an organization that operated as a kind of secret police in Saigon.[11] So, although the album focuses mainly on Quy’s five years at the academy, it also contains photos from an earlier period, when he was as a young boy.

Conventionally, school photos conform to an institutional discourse about the state, in this case, the Saigon-based government of Vietnam, which collapsed with the Communist victory in 1975. School photos also function pedagogically by producing patriotic citizens. The Thủ Đức Military Academy album can be viewed in this way, but we need to consider a broader context, wherein this artifact almost certainly circulated beyond this strictly institutional context, ending up on the open market and who knows where before that. For this reason, it would be helpful to consider this artifact in terms of the broader cultural field in which it was created, not just in terms of a strictly defined genre.

Marianne Hirsch theorizes the “familial gaze” as a concept for grasping the intricacies of these cross-institutional contexts. School photos are usually produced by professional photographers within a public, institutional setting and may be assembled to form a yearbook, as Leo Spitzer and Hirsch argue.[12] Although this album does not contain formal group photos, it nevertheless establishes the school framework through its cover and its depiction of Quy’s fellow trainees. The care with which he assembled his companions’ photos demonstrates his closeness to these men, evident in the cutting of photos to particular shapes and arranging them in a pattern on individual pages.

In addition to its status as a set of school photos, the military album belongs to the discursive mode that Laura Wexler calls “domestic images.” In her analysis of their role in securing US imperialism, Wexler theorizes their function: Such images, she writes,

may be — but need not be — representations of and for a so-called separate sphere of family life. Domestic images may also be configurations of familiar and intimate arrangements intended for the eyes of outsiders, the heimlich (private) as a kind of propaganda; or they be metonymical references to unfamiliar arrangements, the unheimlich intended for domestic consumption. What matters is the use of the image to signify the domestic realm. The domestic realm can be figured as well by a battleship as by a nursery if that battleship . . . is known to be on a mission to redraw and then patrol the nation’s boundaries, the sina qua non of the homeland.[13]

Whereas Wexler’s study draws attention to the ways that white women photographers produce visions of “a peace that keeps the peace,”[14] thereby rendering invisible the violence of US imperial expansion, the South Vietnamese military album presents an intriguing gloss on her concept of domestic visions. Specifically, this album is a male record of domesticity, which through meticulous cutting, pasting, and annotation — the affective labor usually associated with women[15] — sought futilely to secure a homeland by representing a peace against the imminence of violence, a violence that nevertheless inscribed itself on the surface of this record. Thus, while the Thủ Đức Military Academy album does not signify family in a conventional sense — there are no pictures of bourgeois rites, women, or children — when viewed closely, it projects themes of militarized domesticity and homosocial kinship.

When we consider that the activities in the photographs are all organized around the men’s shared military training, the album expresses a keenly felt fraternal love, developed, deepened, and dissolved as part of a story about war that was then still unfolding. We can discern parts of this broader, patriotic war story by piecing together the album’s personal portraits of fraternal affiliation, that is, by looking at the background of the photos, in the spaces between these photos, and even in the gaps of lustrous gilded photo corners that once held images, images that have either fallen out or been removed.

Fig. 6. View of cadet in public garden on grounds of military academy, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, March 4, 1954, 2.5 x 3.5 inches, watercolour on gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 6. View of cadet in public garden on grounds of military academy, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, March 4, 1954, 2.5 x 3.5 inches, watercolour on gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.And yet the album also can be seen to anticipate disavowal as the ultimate gesture in the face of the loss of the nation of South Vietnam. One image seems to eschew memorialization altogether in favor of excision. In a painted photograph of a lone cadet standing in the distance, in a public garden on the grounds of the academy (figure 6), Quy wrote this inscription: “Ngọn cờ VN ðang hùng dủng phât phớ, trên nền trời trong sáng cúa buối minh ðầy hứa hẹn” (The Vietnamese flag flutters crisply on a clear day). Dated March 4, 1954, the photo seems to have been taken less than two months before the French finally surrendered to the Viet Minh at Điện Biên Phủ, on May 7. Significantly, the photo has been cut in a precise line so that there is no sign of the flag mentioned in the inscription: The cropping of the image (as discerned by the missing deckle edge on one side of the photo), which presumably took place after the defeat of the French, marks the next chapter in Vietnam’s history. The unseen hand that removed the flag of an older colonial-order photo anticipates a political erasure, visually reinforcing the divided state of the nation, when new flags for North Vietnam and South Vietnam replaced the one deleted here. Moreover, this act was done so neatly that viewers casting only a glance might easily miss it altogether.

Fig. 7. Portrait of a friend, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1956, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.

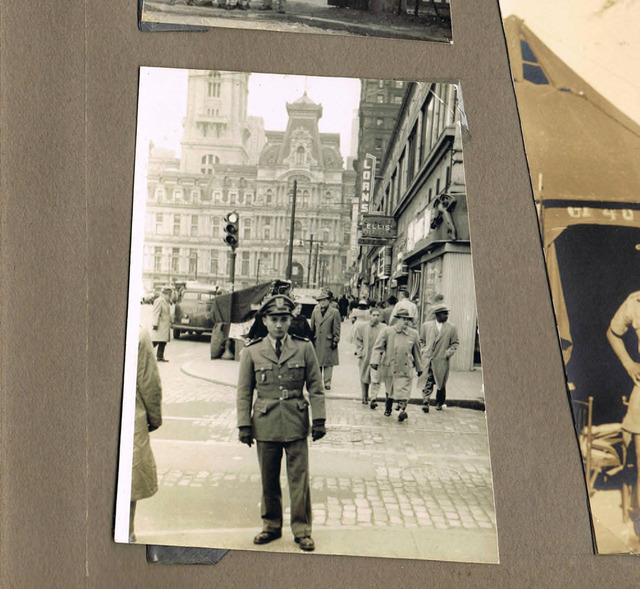

Fig. 7. Portrait of a friend, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1956, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.We can discern the close connections among the men in the album through the ways they exchanged photos with one another, a practice that Quy honors by saving the images given to him. A friend named Thanh dedicates his self-portrait (figure 7), dated March 4, 1954, by inscribing the verso with the following message: “ðể kỹ niệm lúc xa nhau và cũng là lúc tuy không hẹn mà cùng vào quân ðộ” (for you, for when we are far away from each other, and as a memento of our military life). In a second photo, dated 1956, a friend writes to him from an excursion to Monaco, reminiscing of an earlier trip to the United States when he underwent training: “Philadelphia xa rồi, không quên ðýợc những ngày ngắn ngủi ở ðất hoa lệ này!” (Though Philadelphia is far away, I won’t forget my short time in this magnificent land!) Such photos evoke homosocial intimacy, paradoxically expressed through the presumably safe filter of distance.

Fig. 8. Phan Rang studio, Portrait of Long, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, November 19, 1955, 3.5 x 2.75 inches, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 8. Phan Rang studio, Portrait of Long, Thủ Đức Military Academy album, November 19, 1955, 3.5 x 2.75 inches, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the author.On yet another photo, a carte de visite produced by a studio in Phan Rang, a friend named Long writes that he sends his portrait “as a memento of those happy days training in Hàm Tân” (figure 8). Next to his neat signature, Long inscribes in fine black ink the date, 19/11, 1955. Below Long’s inscription, however, someone, perhaps Quy though we cannot be sure, has added a note, using brown pen that bleeds slightly, detailing the fate of the man in the photo. Only ten days after his photo was taken, we learn that Long “Ðã tử nạn ngày 29/11/55 trong khi ði công tác bằng ôtô 4/4 ðýờng Phan Thiết –Hàm Tân lúc 10.00 gìõ” (Died on November 29, 1955, at 10 a.m. during a car accident on a business trip from Phan Thiết - Hàm Tân). This one photograph, then, has an ambiguous double meaning, inscribed as it is by at least two hands, the sender and whoever was the final receiver. This second inscription is even more ambiguous because of “4/4.” Initially, I thought this referred to the Peugeot 404, but it turns out this car model was first introduced in 1960. More likely, the numbers meant that all four passengers in the car died. Indeed, there is a third inscription, Hồ Toài 4.424, the name, perhaps, of the person who informs Quy of Long’s death, though if this is the case, it is strange that he should use a different pen to sign his name than what he used to describe the fate of the passengers.

I have not been able to decode what 4.424 means, though perhaps it denotes the military number of the officer who glossed the photo. Indeed, the coded inscriptions, presumably written for the eyes of the owner of the album, who would have understood their meaning, underscore another layer of intimacy, this time between the owner and the album itself. Still, it is striking that so many fours — considered unlucky numbers in Vietnamese culture — should appear in such a short space. In 1955, according to the inscription, Quy lost another friend, Toan, who died at a battle in Huế, in central Vietnam. Toan’s photo is dated 5.10.55, October 5, 1955. Within the album, then, Quy gathered together his friends, some of whom have traveled far, and a few he would never see again.

Fig. 9. Page from Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 9 x 6.5 inches, gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, courtesy of the author.

Fig. 9. Page from Thủ Đức Military Academy album, 1950s, 9 x 6.5 inches, gelatin silver prints mounted on paper, courtesy of the author.In many cases, however, it is difficult to determine why certain photographs have been placed together, only that great care went into these arrangements: Some images have been cropped closely to focus on the men in them; others are grouped in artful patterns; and in still others, Qúy has clipped away backgrounds altogether, pasting precisely defined figures of the men onto the paper album pages (figure 9). Why he has done this to some images and not to others, why some of the men appear together and not with others, cannot be readily explained. In such pages, where meanings are unreadable, we inevitably brush up against the epistemological challenges associated with unclaimed objects. Long’s photo, for example, reveals his closeness with Quy; that Quy should preserve this photo in his own album attests movingly to the ways that visual exchange and archival preservation serve as a form of memorialization.

It is perhaps fitting that the attachments documented here should come in the form of an unclaimed album, for the fraternal love glued — and torn away — from its pages has been cut from the state-sanctioned meta-narrative of family unification. The story that emerges in the gaps between the photos in the albums, and in the empty spaces where images once were, is a quiet reflection of the men who fought for the ARVN, who have since been cut from mainstream histories about the war in Vietnam. As a whole, the album provides a picture of masculinity of a kind that the Communist state has effaced from official history. That is, it offers an intimate picture of fraternal nationalism antithetical to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, with its depiction of intimate connection in contrast to the disaffiliations that are so pronounced in official memorialization practices. At the same time, the album’s unclaimed and largely anonymous state serves as a potent reminder of national disaffection.

Compiled at a time when the country was partitioned into North Vietnam and South Vietnam, the assemblage of the album attempts to reckon with this division. Its banishment from the familial and to the open market meant that it no longer fit into the political logic resulting from the division. Presumably separated from its owner with the demise of South Vietnam, the album ultimately registers manifold layers of estrangement. Estrangement is indicated not only between the album and its owner and maker, Quy, but also between Quy and the men whom he depicts as his brothers, and between the images and potential viewers of the album who will never know the people they are looking at. The construction of visual kinship establishes not only intimacies but also, it turns out, distances, both between the men who were once so close and from the nation for whose sake these men trained, fought, and died.

The ambiguities I have described with regard to the inscription’s names and numbers remind us of the limits of orphan images; there is only so much we can know and a lot that we may be able only to guess at. The gaps may very well be irresolvable, but they are also in themselves meaningful. Indeed, the paradox of domesticity in images like the photos contained in Quy’s album is a logic of estrangement. Though they depict intimate attachments, their ambiguities also establish distance. As Tina Campt observes, looking at photos of minoritized subjects requires that we respect their epistemological resistance, their refusal to impart their secrets. The critical conceit of historical recuperation risks negating the politics of refusal.[16] Understanding orphan images, then, entails piecing together the histories of which they are a part and to which they bear witness. This task also requires acknowledging — indeed, respecting — such gestures of refusal as themselves meaningful political statements.

By looking closely at the album, then, we can discern how a fraternal community exchanged and preserved photographs to connect with one another and, through collecting these materials into an album, how one man visually constructed a sense of closeness and fraternity with his fellow soldiers, an act that, at moments when distance and excision are evoked as themes, can be seen to anticipate the unraveling of this closeness. Within the discursive framework of the Vietnamese state, in which a national family is constructed in terms of patriotism, wherein men and women became brothers and sisters dedicated to a revolutionary cause, this album projects a competing model of militarized fraternity, an opposing view of national family rendered all the more poignant for its core logic of estrangement and apprehension of impending and irrevocable loss.

About the Author

Thy Phu is an associate professor at Western University, in Canada. Her research centers on the intersections of visual studies, photography studies, and transpacific critique. She is the author of Picturing Model Citizens: Civility in Asian American Visual Culture and a coeditor of Feeling Photography. She is working on three projects: a monograph on the war in Vietnam from the perspective of Vietnamese photographers; a coedited volume on the visual mediation of the global Cold War; and The Family Camera Network, a research collaboration that collects and preserves family photographs and their stories, for which she serves as principal investigator.

Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010): 28.

Christina Schwenkel, The American War in Contemporary Vietnam: Transnational Remembrance and Representation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009). For more on the merging of private rights and public commemoration, see Kate Jellema, “Everywhere Incense Burning: Remembering Ancestors in Ðổi Mới Vietnam,” in Journal of Vietnamese Studies 38.3 (2007): 467–92; Edyta Rozko, “Commemoration and the State: Memory and Legitimacy in Vietnam,” in Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 25.1 (2010): 1–28;

Hu-Tam Ho Tai, ed., The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

See Yến Lê Espiritu, Body Counts: The Vietnam War and Militarized Refugees (Oakland: University of California Press, 2014), and Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). For further insight on the potential of personal material to serve as a counter-archive, see also Evyn Lê Espiritu, “‘Who Was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?’ Queer and Feminist Practices for Exhibiting South Vietnamese History on the Internet,” in Amerasia Journal 43.2 (2017): 3–24.

Olga Dror, “Establishing Ho Chi Minh’s Cult: Vietnamese Traditions and Their Transformations,” in Journal of Asian Studies 75.2 (2016): 433–66.

See Heonik Kwon, Ghosts of War in Vietnam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), and Lan P. Duong, Treacherous Subjects: Gender, Culture, and Trans-Vietnamese Feminisms (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012).

See Thy Phu, “Diasporic Vietnamese Family Photographs: Orphan Images and the Art of

Hon, Binh, Lucy, and Mr. Lu interview with author, Toronto, October 11, 2016.

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, translated by Eric Prenowitz. 1st edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Little has been published about vernacular photography in Vietnam in the 1950s. What we do know is that studio portraiture, what the critic Zhuang Yubin calls “salon photography,” flourished in the first half of the twentieth century. See Zhuang Yubin, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2017). For more on photography in Vietnam, see Nina Mai Hien, Reanimating Vietnam: Icons, Photograph, and Image Making in Ho Chi Minh City (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cornell University, 2007); Ellen Takata, “Photography in Vietnam from the End of the Nineteenth Century to the Start of the Twentieth Century, by Nguyễn Đức Hiệp,” in Trans Asia Photography Review 4, no. 2 (2014), accessed October 7, 2017, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0004.204/—photography-in-vietnam-from-the-end-of-the-nineteenth?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

Ronald H. Spector, “Advice and Support: The Early Years, 1941–1960” (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1988). North Vietnamese domestic intelligence was similarly structured. See Christopher Goscha, “Intelligence in a Time of Decolonization: The Case of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at War (1945–50), Intelligence and National Security 22, no. 1 (2007): 100–38.

Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, School Photos in Liquid Time: Archives of Possibility (forthcoming, University of Washington Press).

Gillian Rose, Doing Family Photography: The Domestic, The Public, and the Politics of Sentiment (London: Routledge, 2016).

Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the Making of the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2012).