Family Intact: The Experience of Being in a Portrait

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

I have often wondered at the motion and commotion that must go on in a family before it is stilled for a portrait photograph. There is an expected simultaneity in the readiness of all members, caught on camera at the moment when bodies, faces, and thoughts seemingly synchronize. Most of the images in the process of portrait making catch us mid-action, mid-thought, producing bodies in blurred motion, looking away or with eyes shut, akin to what M. V. Portman called a “fuzzygraph.”[1] The singular moment of the final portrait coexists with temporal extensions before and after, tempered with permutations in gesture and posture. Embedded in these extensions are clues to the family’s logic, its proximities and distances, its politics, its loves and losses. They may not be easy to decode for an outsider, but are familiar to those who have posed for the image.

An opportunity to understand the family portrait from the multiple perspectives of the viewer, sitter, critic, and collector offered itself in July 2017, when the artist Dayanita Singh decided to photograph the Sinhas, my parental family. The possibility came as a surprise, for we had known her for more than twenty years, yet she had never before requested to photograph us.[2] At a certain defining moment in her career, in the 1990s, Singh made photographs of her friends and family who were similar to herself in class and cultural background, sequencing them in a seminal body of work titled Privacy.[3] Naturally, when she asked to photograph us, my frame of reference was that series and I imagined our portrait as a continuation of that project. Despite our professional interests in photography, neither my mother, the art critic and historian Gayatri Sinha, nor I had imagined entering the frame ourselves.

Singh’s impulse to photograph us, she said, came from the sudden realization that the women in our family, so familiar to her as children and young women, were now growing, transforming, and departing. She had wanted to photograph us before we changed completely from how we had been in a nuclear unit, with my sister and me as children, not adults and mothers, and my mother as mother, not grandmother. This is something she had noticed across the families of several close friends, and she had similarly entered their homes with her camera to hold on to a rapidly passing age. This entailed revisiting some of the families in Privacy, and looking at new subjects among old friends, like us.

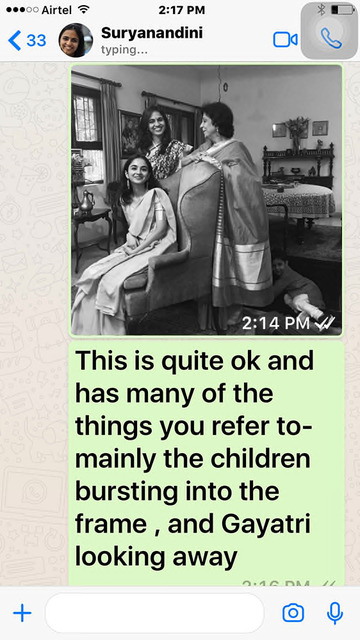

Fig. 1. Singh, Dayanita, view of test image of Sinha family portrait on WhatsApp, 2018, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.

Fig. 1. Singh, Dayanita, view of test image of Sinha family portrait on WhatsApp, 2018, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.Three generations of the maternal line of my family faced this photographer’s lens for the first time. The conversation during the photo session oscillated among topics such as femininity and domesticity, our friendship with Dayanita, and the history of photography. This essay draws from a rumination between me and my mother, about what it felt like to be photographed by Dayanita Singh. Interwoven are my own reflections and readings. After the session, looking at the portrait as test images sent on our phones by the photographer, which reflected different versions of my mother, my sister, and me arranged around a chair in the living room, evoked surprise and introspection (figure 1). Using these unexpected reactions and emotions as an entry point, my mother and I later reflected on our portrait session, the resulting images, and how they related to what we know of Singh’s work. This essay traces continuities in practice and convention and delineates visible departures from expectations in being photographed. It also explores whether Singh’s images reinforce or challenge the classic metaphors of family portraiture, and whether an oral articulation of the experience expands or displaces the visual frame.

This conversation was invoked by a set of four test images, not final edited versions, sent via WhatsApp by the photographer. One among these has been included in this essay, along with the text message she had sent me. Conversations with Singh over the past year have revealed the hidden complexities of the editing process, the most absorbing and challenging part of her work. The edit of our family portrait is still ongoing as I write this essay. For Singh, it is achieved only at the right moment - displaced from the moment that the photograph is taken onto the moment that the image reveals itself, beckoning dialogue with the maker, and commencing a journey from the editing table into the world. As we await the final, edited portrait, I reflect at its genesis and imagine its future.

Context

The art of Dayanita Singh (b. 1961) uses photography to reflect and expand on the ways in which we relate to photographic images. Her recent work, drawn from her extensive photographic oeuvre, is a series of mobile museums that allows her images to be endlessly edited, sequenced, archived, and displayed. Stemming from Singh’s interest in the archive, the museums present her photographs as interconnected bodies of work that are replete with both poetic and narrative possibilities.[4] Publishing is also a significant part of the artist’s practice: In her books, often made in collaboration with Gerhard Steidl, she experiments with alternative forms of producing and viewing photographs. Singh’s latest project is the “book-object,” a work that is concurrently a book, an art object, an exhibition, and a catalogue. This work, also developing from the artist’s interest in the poetic and narrative possibility of sequence and re-sequence, enables Singh to both create photographic sequence and simultaneously disrupt it.

Singh’s photographs are seldom about stillness or a final frame. They most often capture bodies and minds in motion, and in them we find truths about familial bonds. Temporal transition is measurable to Dayanita Singh through the women of the various households she has come to know. She has wanted to visually freeze moments in a feminized timeline. Her centering of women is a trope that can be traced to nineteenth-century modern India, in addition to the impact of cinema and the visual arts. In our case, our networks of friendship with her were through the mother-daughter-sister matrix; it excluded father, husband, and son.

Should our portrait fall into the hands of someone outside of this circle, the reason for the female focus may be decoded differently. Christopher Pinney, writing on photography’s meaning in anthropology, comments on the colonial perception that women were the bearers of culture in society, the very anchors of tradition, the last to change.[5] By looking at them, according to anthropological knowledge, one could know about core sociocultural beliefs and values. Their presence in ethnographic images, or the collection of “types” in series such as the People of India (1868), was important to a colonial administration that wanted to grasp the realities of the people they were to rule.

In my family portraits, I could see a sense of temporality, but one different from a colonial understanding. I could see how the three central women — my mother, my sister, and I — were bearers of time. We embodied both change and stasis, differing not only generationally but also through personal choices that informed our bodies, our gazes, our dialogues with the lens. The tension lay in the dynamic qualities borne by the three women in the portrait, each transitioning from one familial role into another: indeed, into one another’s roles, with the daughter who has now become the mother and is protected by another mother in her period of transition.

This temporal quality contrasts with the timeless quality of Singh’s black-and-white style, our classic drawing room furniture shaping the stable pyramidal montage, our traditional clothing in the form of the sari draping each of us. Indeed, the semi-colonial interiors of our home give no sense of a passage of time. My mother explains this perceived timelessness as something we as viewers and the photographer have both contributed to: “we confer our memory of other timeless portraits upon what we see in her pictures, the classicism, the framing, the formality, the black-and-white . . . are all remnants of the forties and the fifties, something she would have of course picked up from Nony [Dayanita Singh’s mother, who photographed extensively], because that is her direct inheritance, but also her interest in extracting her subject out of a social context or a political context and putting it in a class context.”

Class and kinship are definitive axes in Singh’s visual choices, surfacing through every detail in the frame. Women, as were conventionally perceived by our colonial surveyors and administrators, still communicate important social parameters in the family photograph, although not always in expected ways.

All four digital test images from our family-portrait session seem to vary between extremes: a social awareness and a private involvement, conscious of being a visual exemplification of class but also an exploration of individual emotions that animate the sitters. There is composure in the mutually supported bodies, rupture in their momentary destabilization, and then their visual submergence in the photographer’s archive.

Composure

The portrait is an intimate experience because Singh’s practice is to come into the familial fold to make it. Singh aligns herself to the pulse of the household, centering herself amid our crisscrossing gazes to catch the tonality of the image in the making. The “tone” of an image in the sense that Singh hears it is a difficult concept to explain. Although silence seemingly envelops her photograph, Singh is listening to the “pitch” at which it resonates with her and with all of her other images. It is this “tone” that guides her in the editing process, of which she says elsewhere, “I have finally learned to listen to the tone of images, rather than edit by content.”[7] Spoken of by the photographer in several conversations with other people, this tonality helps her register the photograph in her larger oeuvre, further locating the image in her family of museums next to neighbors, relations, friends.[8] Making the act of portraiture is an intimate yet constructed experience. In Singh’s work, the photographer and the photographed are equal agents and the portraits are also domestic pictures. “The rest of the world never impinges onto the domestic interiors that are very carefully controlled. Even the servants of the household, unless they really add compositional value, are completely excluded,” observes my mother.

There is nothing accidental in the choice of the frame, that may include the tumbling child, the passing servant, the scampering dog, as in one of the test portraits (figure 1). These bodies in motion add/extract/bring to the surface certain indices that make the chief figures readable.

The same can be said about the inanimate elements in the frame. Furniture, upholstery, cultural bric-a-brac, each add to the photograph’s internal character and narrative. The grandiose purple armchair is the glue that binds the bodies in our portrait. It was a gift from Mrs. Dadachanji,[9] the widow of my father’s professional mentor, as she was emptying her life of the things that belonged to her own household. The chair came to our house and became the central element of the drawing room. It was chosen by Dayanita to position us for the portrait. We crowded over it and around it, barely leaving any of it visible. It formed the backbone of the montage as we took turns to occupy it, as if enhancing the central sitter.

As a chair burdened with bodies, it is not unlike the empty heaviness of the chairs Dayanita exhibited at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 2005. There is an affinity between Singh and chairs; for the artist, they seem to retain a residue of a person even after the person is gone. Loaded with absent sitters or their ghosts, Singh’s work showing empty chairs portrays a retreat of bodies from the places where they had been, retaining traces of their sitters’ personalities. In our family photograph, despite the heavy history of sitters associated with our purple armchair, the reverse seemed to happen as we conferred on the chair the role of foregrounding us. I wonder whether Singh took a photograph of our purple armchair while it was empty, before we arranged ourselves around it. If she did, I am unaware. And strangely, I cannot imagine such a photograph. My own memory of the making of our family portrait is dominated by the people in it, all other elements serving as accessories.

Materiality and maternity are odd companions in Singh’s work. They layer onto each other and come to aid one another in the construction of familial solidarity. My mother identifies this bond as a reflection of her relationship with Nony Singh (b. Ranjit Kaur, 1936), Dayanita Singh’s mother and a photographer whose work, as Sinha puts it, spoke about the “sheer materiality of her existence”— the house, rooms, files, and the material residue of litigations. “The materiality of Nony dressing up her daughters is important because it is play acting. There is no mise-en-scène, there is no particular stage,” Sinha comments. They dress up for the camera, creating an event that is portrait-worthy for the mother to visually document her family. Nony took pictures of Dayanita and her sister, Nikita, before they went out. My mother calls these “notations in time,” of a personal, idiosyncratic, and affect-laden timeline whose logic was internal to the Singhs.

Dayanita did to Samara Chopra, one of the subjects in her work, what Nony had done with her. Indeed this is perhaps what most families do to mark time. “Our mother did this with us,” says Sinha, reflecting on her own childhood. “Every summer holiday we were photographed, every winter holiday we were photographed, every school play was photographed, so these were, in a sense, acts of transition in time.” The notations may be spaced close together or farther apart — a matter of days, months, or years between them. Or they can split into milliseconds as the camera’s shutter clicks away at the same sitting. “Time” is fluid in the memory of the mother who chooses to remember or forget parts of her family’s history. In the end, the photographing mother lovingly compiles an album, recalling the moment as always being in excess of the final photograph. In this sense, Museum Bhavan (2017), a book-object containing themed-sequences of images in accordion-book formats, can be understood as Singh’s family album of which she is the mother.[10] It is endlessly in motion, variable in arrangement, with parts of it stored away or pulled out for display at her discretion.

Fig. 2. Singh, Dayanita, Valentine’s Day, Calcutta, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.

Fig. 2. Singh, Dayanita, Valentine’s Day, Calcutta, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.Access

My mother and I have this conversation in the middle room of our house, the place where my mother usually sits and writes, looking out at the trees from the glass door on the right, managing the activities of the kitchen on the left. This is where the drawing room ends in one door and the bedroom begins through another. It is where we can fathom the publicness and privateness of the other rooms, and sit back with a certain perspective on both. Singh’s images occur in drawing rooms and bedrooms — the two extremes of any household — never in kitchens or gardens, which are places of movement and activity. Sitting rooms are spaces of repose, stillness, social presentation of the self to the world; bedrooms are intimate interiors out of bounds to the visitor. Bedrooms are spaces of rest, preparation, intimacy, and death.

Body demeanor in either domestic space is radically different. The young woman who readies herself in her boudoir, flattered at her figure in the mirror in “Valentine’s Day, Calcutta, 1997” may pose demurely with her parents in a family portrait in the drawing room (figure 2). The girl denying eye contact as she buries her face in the bed in “Go Away Closer” (2007) may look at the camera and perhaps even smile for it, as in the portrait with her mother in the sitting room, “Rita Dhodhy and Daughter, Bombay, 1997” (figure 3). The presence of the same family in the bedroom makes the drawing room seem like a theatrical space. The photo studio is transposed onto the drawing room and the bedroom peals back the props. These are two extremes of exposure, of composure and visual access. The camera’s presence seems welcome in the drawing room and invasive in the bedroom, yet Singh’s access is to both.

Fig. 3. Singh, Dayanita, Rita Dhodhy and Daughter, Bombay, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.

Fig. 3. Singh, Dayanita, Rita Dhodhy and Daughter, Bombay, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.Sinha finds that Singh, as the auteur and agent of the image, does not actively direct the family sessions, unlike other portrait photographers, such as Annie Leibovitz (b. 1949). Privacy shows people in their own environment, and Singh works within defined parameters with them. Our drawing room is where we have had numerous conversations about photography with her. Even on the day we are being photographed, we spoke about Hippolyte Bayard (d. 1887), who feigned his own death before the camera to indicate how the photograph is essentially a lie about the living.[11] Family portraits, on the other hand, are a bid for one’s place in eternity.

The theater of the drawing room and its classicism, its timelessness so particular to Singh’s framing, all enable the bond of kinship to stay intact. Any excess in the composure of the figures, to the degree that they seemed like they were acting the part, would have been like Bayard’s attempt to show the truth of a lie, to defeat the camera’s truth function in favor of its ability to construct a convincing artifice.

“She doesn’t want to explain the family, in fact it mystifies you, it makes you want to know more, but she wouldn’t want to put them in such a dramatic manner of play so that it totally deceives the viewer of the meaning,” my mother concludes.

Fig. 4. Singh, Dayanita, Guptoo Ladies, Calcutta, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.

Fig. 4. Singh, Dayanita, Guptoo Ladies, Calcutta, 1997, © Dayanita Singh, courtesy of Dayanita Singh.Rupture

The portrait visually produces the family as intact, even as evidence may indicate rupture. Julia Hirsch describes the family portrait as one that allows the viewer to look at the family but not into it.[12] All the people look the way they ought to look, concealing the disturbances. But the Sinha family portraits, like several in the Privacy series, are far from being stable. Each image reveals the personae of the sitters, who relationally define themselves. My mother, for example, barely looks at the camera, distracted as she is by the grandchild tumbling off the armchair, or focused as she is on either of the daughters needing her attention in different ways. She explains this, saying that the truth of her maternal nature justifies her presence in the frame, “otherwise I wouldn’t know what I’m doing there.” Status is not conferred on her by the convention of the image. Instead, assumptions are pulled back to reveal her self-determined familial role.

Likewise, my sister, Katyayani, sits poised self-consciously, gazing with a degree of ambivalence at the camera. She is someone who has inherited knowledge about the visual world and the camera’s activities by virtue of the conversations her mother and sister (me) have had in the house over the years. Singh’s numerous visits to our home have made Katyayani privy to the periods of departure and coming together in our relationship with her, both personal and professional. Self-presentation comes to my sister effortlessly; she is well versed in the modalities of the selfie and social-media images in which photographing the body is not an exceptional event. Requiring little preparation, it is Singh’s gaze that makes the portrait session a special moment.

Katyayani’s youth infuses her with a confidence and an assurance in knowing image politics. My father’s absence in several frames is indicative of female predominance in this family, mainly because Singh’s friendships are with the women of the family and he is peripheral to it. My mother notes that his presence, even if minimal, is not a comfortable one for the rest of us. “He brings a lack of certitude, a lack of communication,” she says, “and we start responding to his isolation. Is he impatient? How long will this take? These are all valid questions.”

There are several such portraits of multiple generations of women in Privacy, such as “Guptoo Ladies, Calcutta, 1997,” “Amrita Zaveri with Sisters, Bombay, 2002,” “Minni Sodhi, Her Mother and Daughter, New Delhi, 1992,” where there are no male spouses in the frame (figure 4). There is also the image of a father with children draped around him in “Cyrus and Simeen Oshidaar and Family, Bombay 2002,” grounding him in a way with the other bodies acknowledging him, holding him down. If this kind of montage was not there, he would fall outside the frame; that is, in Singh’s work, unless you embellish the father with bodies of the children, he won’t be visually legible.

And yet, conjugality is tangentially referenced even in the absent or subservient presence of the husband. This is discerned through the demeanor of the women, the interior of the household, the very mode of the photograph. My maternal grandfather was the family photographer. When he passed away, at a young age, he left his Rolliflex to my grandmother to continue documenting their children. My mother was only two years old at the time of his death, and felt that her father thereafter was embedded in every family photograph even long after he was gone.

The portrait session with Dayantia Singh was punctuated with arrivals and departures: father left for the office less than midway through, mother went in and out of the kitchen several times to look at lunch, and my son Agastya came in toward the end, destabilizing the pyramidal structure of the family during the sitting. Katyayani and I constantly changed positions as central figures in the frame, seating ourselves on the armchair. Dayanita advised us to hold hands, lean onto each other, look at each other and chat. That was the extent of her direction, often seamlessly part of a conversation that contained references to friends and photography. Each rearrangement of the family emphasized different relationships. There are several moments of instability. “She does this again and again in Privacy . . . suddenly the child enters, and the formality of it all slips,” says Sinha.

The child is identifiable as one of the tropes Dayanita uses in order to unravel the family portrait, as seen in “Pal Choudhuris, Calcutta, 1997” and “Grandmother’s Princess, Bhopal, 1996.” But, then, who may be the child in the Sinha family? Is it either or both of the daughters? The elder daughter is a mother already, but appears central to the portrait in such a way that she becomes a child being protected by the others while she undergoes a precarious pregnancy. She is the child even as she is a mother. Katyayani, the younger daughter, is a few days shy of turning twenty-one, at the cusp of adulthood, evolving the definitions of her persona, again protected by her parents. There was one shot for which she even sat on my lap, with no parents to surround us — and in this moment I turned into her mother. Is the child the grandson who enters the frame in the last few images? Agastya is physically the odd element in the montage, now drawing the grandmother’s attention away from the nuclear unit as he sprawls on the ground, now hanging onto the end of his mother’s sari, now balancing his body upside down on the arm of the chair, insisting on throwing askew all the items that had been carefully melded together to prop the family as a stable unit. Or is the child the unborn one I am carrying, invisible to the viewer, even outside the photographer’s knowledge, but informing the protective stance of each family member?

It is for this reason that I had come home to stay for a prolonged period, already creating a variance in the pattern of everyday living for the members of this household long before the portrait session. Child-mother, mother of child, and child of a mother mutate into one another’s subject positions, giving the sitters reason to belong together and alter the central montage. My mother leaves the frame as she chases Agastya, Katyayani slumps as she tires of the photographic process, and I look on, intensely aware with the knowledge of my own changing biology: The child in each of us destabilizes the previously static montage.

Gestation/Archive

The format and placement of photographs in the home is to sustain a family’s dialogue with its past. We have seen only test images, but we can’t help but think ahead to the finished portrait. Where will we put it? Who would have access to viewing it? Which family pictures are only for private perusal, usually kept in albums, in wallets and pockets, and hidden in private bedrooms? Which have a more public presence? Singh explores this idea in her Sent a Letter series (2008), with small images in accordion-book format that can be carried around, gifted, given, hidden, exchanged. Samara Chopra appears with her family in one such accordion book, growing before our eyes in minute but significant ways. These images contrast with the scale of the photograph of Pooja Mukherji and Samara that had been displayed prominently on the walls of the National Museum, as part of the exhibition Middle Age Spread (2004), curated by Sinha. The accordion book invites the viewer into its folds, to linger and savor, while Mukherji and Chopra, in the larger frame, look outward challenging, if not confronting, the gaze.

My sister and I clear wall space in our drawing room for our imagined, final family portrait, which we hope is in large format. We don’t have the picture yet, we don’t know which one Dayanita will frame and give to us, and what that image will finally tell about ourselves. Yet it will be the boldest act of self-presentation for the Sinhas thus far, opening our home and ourselves to those who visit to know us better.

Our own family photographs, taken by mother, father, grandfather, or my wedding photographer may sit shyly next to Singh’s portrait of us. Smaller, hazier, more tentative in technique, our childhood photos, framed above the piano or on the sideboard, brim over with affective content. Tucked away in drawers and cupboards in my mother’s home office are albums with colored shots on Kodak paper, small Rolliflex frames in black-and-white, with stories to be whispered to their viewers within the tight circle of the Sinha family. More still lie in our computers and phones, too many to count, too many to print. These may never have an audience beyond the four of us. Would the Sinha portrait by Dayanita Singh stand in for the hundreds of its sisters that did not make it to the drawing room wall?

Through the family photograph, we are mutually part of one another’s archives. This is an unprecedented moment when we came together as a family to have our photograph taken by a professional. The final image, which will be enlarged and framed for the drawing room, will be the cover page of our family memory. Although the image is of a fragment in time, its instabilities particular to the second when the shutter clicks, the singular family portrait acquires an eternal quality. The family portrait’s position of posterity in the home, displayed directly in the line of vision of all who visit, will give it a life that is far greater than the moment in which it was made.

For Singh, perhaps we will be in her Museum of Love, or Museum of Little Ladies, or Museum of Chance. Or perhaps we will never make it into one of her museums, for our image may not harmonize with that of another family. We could never be friends with our neighbors. At an intellectual level, we will reference each other as friends who saw one another through the lens. We will know this as a moment when the photographer and critic reversed gazes, a phenomenon not uncommon to several photographers and critics across the world.

“The image acts as an equalizer in a certain sense, tipping the balance one way or the other,” says my mother. The outcome is the unexpected moment of the critic viewing herself in the photograph, through the language of the photographer she knows so well. Suddenly, a hundred other images by Dayanita seem closer than they have ever been before, now that we are sitters too.

Suryanandini Narain is assistant professor of visual studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. A recipient of scholarships from the Ford Foundation, INLAKS, and ICSSR, she has also been an assistant editor for various MARG magazines and volumes. Among her areas of interest are visual culture, popular Indian art, and photography.

In his directives to guide field photography, in “Photography for Anthropologists” for the Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 25 (1896), 75, Portman identifies the aim of anthropological photography to “get great and accurate detail, not to make pictures. ‘Fuzzygraphs’ are quite out of place in anthropological work.” The term fuzzygraph refers to the blurred image that results from an error in equipment or technique of photography, when the subject or the camera moves unexpectedly and inconveniently. It is these very motions, unexpected and inconvenient in their revelations of the truth, that inform Singh’s family photographs. What seems erroneous to anthropological inquiry of a colonial nature is both aesthetically and factually enriching for the narrative of a family photograph.

Dayanita Singh has been known to my mother, Gayatri Sinha, for more than twenty years. She has been part of my mother’s critical writings on photography, and curated photographic exhibitions such as Faultlines, Mumbai (2008), Middle Age Spread Imaging India 1947–2004, at the National Museum, New Delhi (2004), Woman/Goddess 1999–2000 in Delhi, Bombay, Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, and New York (2001). As one of Sinha’s daughters, I have grown up with Singh’s images in visual, verbal, and textual references. As an academic interested in photography, I have engaged with them intellectually. Now as a sitter in one of Singh’s family portraits, I suddenly became one of the referents.

Privacy, with texts by Dayanita Singh and Britta Schmitz. 2004, Steidl.

In Camera Indica (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1997), 29, Pinney says about ethnographic images that “this quest for difference tended to make the women of a group of more interest, since their costume and material culture were identified as being more resistant to change.”

Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning and Effect (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 10, 12.

From http://artradarjournal.com/2016/03/22/museum-bhavan-dayanita-singhs-photobooks-and-their-ever-evolving-narratives/.

I refer to Museum Bhavan, by Dayanita Singh, the “museum” in book form and the traveling exhibition of the same title (2017). Museum Bhavan as a book-object is a series of accordion-format books containing sequences of her photographs grouped under a theme. As an exhibition, the images are part of large wooden display structures that can be changed around. These portable museums have been shown in London, Frankfurt, and Chicago; in Delhi, the artist had installed nine museums from the collection. Each holds old and new images, from the time Singh began photography in 1981 until the present (from http://dayanitasingh.net/museum-bhavan/). In Museum Bhavan, several smaller museums adopt relations of kinship to each other, as, for example, “sister museums” and “mother and daughter” museums. Dayanita is maternal about all her museums.

J. B. Dadachanji was an eminent Indian lawyer. He died in 2007 and is survived by his wife, Dolly Dadachanji.

We were referring to Bayard’s famous “Self-portrait as a Drowned Man,” taken in 1840.

Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning and Effect, 97.

Dayanita Singh, “A Photographer’s Daughter,” Privacy (Göttingen: Steidl, 2004).