Diaspora and Performance: Reenacting the Family Album

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

In the second shot of Aisuke Kondo’s six-minute video, The Past in the Present in SF (2017), a tree trunk fills the frame.[1] An outstretched hand reaches from the camera toward the trunk (figure 1). Then, the video opens to the entire tree, a palm in front of the Conservatory of Flowers in San Francisco. Hands from behind the camera slowly raise a black-and-white photograph of a middle-aged man, wearing a suit and hat, in front of the tree (figure 2). The video cuts to the same shot in the present-day (figure 3). Instead of a middle-aged man, though, in his place a young man stands dressed in jeans and a sweatshirt. The video’s artist, Aisuke Kondo (hereafter Kondo), is the young man and the man in the photograph is his great-grandfather Miki Kondo (hereafter Miki), a man whom Kondo never met. Kondo’s outstretched hand in the opening sequence seems to reach across time and place to connect to a family member and fellow immigrant.[2]

Fig. 1. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 1. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 2. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 2. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 3. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 3. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.Born in 1980, in Shizuoka, Kondo left Japan for an education at the Berlin University of the Arts. He remained there and made Berlin his home base. Kondo’s art practice, spanning photography, installation, video, and performance, takes him abroad frequently —he has exhibited in Japan, South Korea, and the United States, where a 2017 residency provided him the opportunity to visit the places in which his great-grandfather lived.[3] Miki was born in Japan in 1882 and in 1907 left the country in his mid-twenties to immigrate to the United States. He settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, working for a dry cleaning business, and started a family with Kiyo Kurihara, also from Japan.[4] In 1942, Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 resulted in the mass relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps.[5] It forced Miki first to the Santa Anita Assembly Center, in Southern California, and then to the Topaz War Relocation Center, in Utah, where he was held for more than two years. After his release, in 1945, Miki, unable to return to his former life in San Francisco, worked for a dry cleaner in Ely, Nevada, until 1949 and cleaned houses in San Francisco from 1949 until 1954. When his grandson, Kondo’s father, was born, he returned to Japan; he passed away two years later in Shizuoka. Although Miki’s eventual return to Japan after WWII is unusual, his history of migration and displacement is typical of the Japanese diaspora in the late nineteenth century, when laborers left Japan for Hawaii and North and South America.[6] His experiences reflect the long separations and obscured histories of Asian migrants that resulted from US anti-immigration legislation and forced relocation. This article considers how the Asian diasporic experience in the United States shapes practices of representation in family photography and readings of the family album.

I focus on Kondo’s The Past in the Present in SF because it elucidates the ways in which the historical conditions of diaspora necessitate alternative approaches to the family photograph and album. The Past in the Present in SF offers one such approach — reenactment. In the video, Kondo displays his great-grandfather’s photographs and then replicates them. Scholars have described the family photograph as transmitting ways of seeing and knowing how the family realizes social and cultural values.[7] When Kondo re-creates Miki’s photographs, he connects to his great-grandfather while he calls attention to the family photograph’s mechanizations. The Past in the Present in SF illustrates that, more than a mode of seeing, knowing, or understanding family history, the family photograph is performative — it enacts a doing. Describing family photography as “a critical medium through which diasporic relationality is constituted,” Tina Campt asserts that “it is a performative practice that enacts complicated forms of social and cultural relationships.”[8] Along these lines, this article teases out the performative role of the family album in a diasporic history of movement, belonging, and displacement. As I argue, Kondo’s embodiment highlights the performative practices of the family album in two ways. First, by embodying his great-grandfather’s poses, Kondo identifies Miki’s photographs as performative practices of assimilation, at the same time questioning Miki’s ability to belong.[9] Second, the video’s collection and organization of Miki’s photographs demonstrates new ways of interacting with the family album, better suited to the separation and distance of diaspora.

The Past in the Present in SF is further situated in the neglected visual field and historical narratives of the Japanese diasporic experience. The images of Miki occupy an underdeveloped interstice between photographs of Japanese taken by foreigners, such as Felice Beato, in the mid-nineteenth century for circulation in the West and photographs of internment-camp life during WWII. Given the quick adoption of photographic techniques in nineteenth-century Japan and the popularity of photography studios, it is likely that Miki came across or had taken photographs before he moved to the United States.[10] Until the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, immigrants experimented with new artistic techniques in photography clubs. Yet these amateur clubs, according to Dennis Reed, worked in the style of pictorialism, not the casual shots as featured in The Past in the Present in SF.[11] Instead, Japanese internment camps dominate the twentieth-century visual register of diasporic family photography. According to Thy Phu, this mass incarceration “marks the introduction of Japanese Americans to US visual culture.”[12] In contrast, The Past in the Present in SF locates and foregrounds a visual history that occurs entirely before WWII in the form of Miki’s photographs.

The Past in the Present in SF is the first work in Kondo’s Matter and Memory series (2017–present), in which Kondo travels to the United States to retrace his great-grandfather’s life. The Past in the Present in SF focuses on photographs from Miki’s time in San Francisco between his arrival in the country, in 1907, and his forced relocation, in 1942.[13] Left behind in Miki’s memorial artifacts, the photographs were acquired by Kondo when he visited his grandmother in Japan. Kondo knew of the existence of these albums since his childhood, but many of the details of Miki’s life had long been lost. In the video, Kondo displays and replicates Miki’s photographs to reenact a family album shaped by temporal and spatial distance. The images visually relate Kondo to his great-grandfather, but they simultaneously betray historical omissions and lost connections. Photographs of Miki appear without accompanying information such as the date of the image or Miki’s reasons for posing in front of area landmarks. Generational distance and Miki’s prolonged separation from his family have prevented these details from reaching Kondo and, by extension, us. As I will explore, when the video shows Kondo re-creating his great-grandfather’s photographs, it calls attention to the ways in which diaspora shapes the lives of immigrants and of their descendants.

The Diasporic Subject Performs

In The Past in the Present in SF, the family photograph expresses the social customs and values performed by the diasporic subject. Catherine Zuromskis discusses the complex position of the casual family photograph, what she calls a “snapshot,” as deeply personal and also embedded within “a naturalized set of hegemonic conventions regulating private snapshot acts and images.”[14] The photographs in The Past in the Present in SF similarly negotiate between the personal and the societal.[15] When Kondo reenacts his great-grandfather’s poses, the video identifies aesthetic conventions of the family photograph and norms of diasporic life as it situates Kondo’s great-grandfather within them.

Fig. 4. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 4. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 5. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

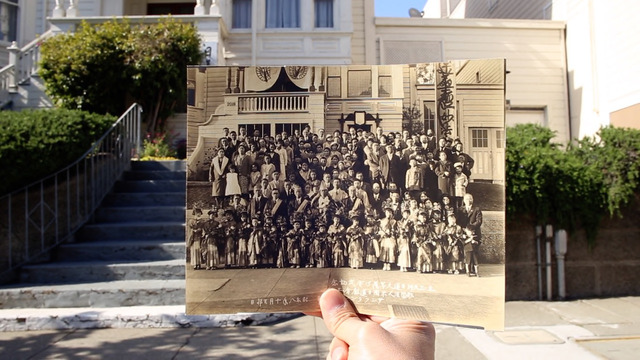

Fig. 5. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.Miki’s photographs are not about what Anthony Lee has described as a “development of strong and sustaining memories of a homeland” but rather a desire to set up roots and engage with Miki’s new surroundings.[16] In this way, The Past in the Present in SF seems to trace the diasporic subject’s work of expressing identity, what Stuart Hall describes as “producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference.”[17] That is, the vintage photographs in The Past in the Present in SF show Miki’s efforts at integration and assimilation. He is shown in what appears to be his typical dress, including his preference for suits, and his smiling disposition, seemingly content. Other photographs portray Miki in the middle of groups of men to suggest that he participated in a Japanese immigrant community (figure 4). Another photograph, of a group of adults and children, highlights that Miki is well situated within his community and further identifies his standard dress (figure 5). In what seems to be after an event, perhaps a dance or a pageant, the group stands in front of a Japanese temple. The children, in kimonos and holding flowers, demonstrate the cultural activities that are maintained by diasporic subjects. The contrast between children in kimonos and adults in Western-style suits and hats implies that the children participate in this cultural event, carrying on traditions from Japan, while their parents encourage them from the audience. In this way, the photograph documents acts of cultural transmission from Issei (first-generation immigrants) to Nisei (children born in the United States).

The very existence of family photographs suggests that the genre itself can be considered an act of assimilation. The photographs are a testament to the fact that part of Kondo’s great-grandfather’s life in San Francisco was documenting it, that is, the practice of taking photos. In The Past in the Present in SF, this act becomes a diasporic one —a mode of connecting to a new place of residence. Campt asserts that the photograph establishes the diasporic subject within his or her new home. In her study of African diasporic subjects in Germany, family photographs “underscore . . . more emplaced forms of belonging and unbelonging, and in the process, they emphasize the ways in which that diaspora is also quite fundamentally about dwelling and staying put,” and Campt contrasts these performances of belonging with “signs of displacement or marginality we most frequently associate with a conception of diasporic migration or acculturation.”[18]

Photographs of Miki make him part of the landscape despite his legal standing in the country. As a first-generation Asian immigrant to the United States, Miki was not able to attain citizenship until after World War II.[19] Against his citizenship status, photographs of him in front of well-known locations serve, in the words of Roland Barthes, as “certificate[s] of presence.”[20] In the first shot in the video, Miki appears in front of Stanford University’s Memorial Church (figure 6). When The Past in the Present in SF inserts the photograph in a contemporary video of the location, it highlights and reinforces Miki’s act of settling in.

Fig. 6. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 6. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.Looking at Miki’s photographs on their own, they stage a narrative of belonging, leisure, and joy. Smiling in all of them, it seems that Miki has assimilated into American life. The group shots further suggest that Miki has found a community. One could hypothesize that Miki was happy in the Bay Area, and one could assert that Miki’s appearance anticipates the prosperity of Japanese Americans after World War II. Miki’s suit distinguishes him from immigrants in the service, agricultural, and construction industries to imply that he achieved some kind of success. The narrative of Miki’s upward mobility in the United States, from his humble entrance into the country to his stylish clothing in the photographs, reflects the model minority myth that emerged in the 1960s to describe Japanese American success in the face of past adversity.[21] As Phu writes, the model minority myth “casts a long shadow that continues to influence debates on citizenship today” and is “no less injurious a stereotype as the Yellow Peril specters that it ostensibly replaced.”[22] Initially deployed by conservatives, the model minority myth pits Japanese Americans against other minorities to argue against the civil liberties movement.[23] Accordingly, it downplays former racist immigration policies, such as the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 and the Immigration Act of 1924, and reframes the forced relocation and incarceration during WWII as hardships that determined future economic success.

In reality, however, we know that immigration legislation and wartime incarceration had a negative impact on Miki’s life. An anti-immigration storm had already been brewing during the many decades when Miki was in America. He had moved here before the Gentlemen’s Agreement severely restricted Japanese immigration. When the United States passed wave after wave of anti-Asian legislation, Miki was permanently separated from his wife when she went back to Japan with their young son and then was unable to return. In 1942, Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 removed Japanese immigrants from their homes and land; it stripped them of their constitutional rights, left many in a worse-off economic situation, and gutted their communities across the West Coast. After the war, Miki no longer had a home in San Francisco, so he initially remained near Topaz, working for a dry cleaning business. When he did return to San Francisco, in 1949, he cleaned houses — demanding physical work for a man in his mid-sixties. Although Miki returned to Japan in 1954, after the birth of his grandson, the harsh treatment he had experienced at the hands of the US government, along with diminished prospects after the war, must have eased his decision to leave the country.

By contrasting Miki with his great-grandson, The Past in the Present in SF anticipates Miki’s hardships. Kondo’s embodiment troubles any easy understanding of his great-grandfather’s immigration, displacing it from the model minority narrative. When he stands in for his great-grandfather in the present day, Kondo does not attempt to re-create his image exactly. Instead, he appears in contemporary dress, in jeans, a sweatshirt, and sneakers. He only re-creates his great-grandfather’s pose, standing alone when Miki appears in a group of people. Despite the seeming reenactment, Kondo’s body invites comparisons to mark the differences between Kondo and his great-grandfather, the present and the past. When the video juxtaposes Miki’s vintage photographs with Kondo’s re-created ones, The Past in the Present in SF evokes a representational strategy of marking difference prevalent in the “before-and-after” photograph.

According to Kate Palmer Albers and Jordan Bear, in before-and-after photographs, the “perceived gap between these images employs — and troubles — two kinds of photographic conventions, both of whose continual interrogation have been central features in the historiography of the medium.”[24] Albers and Bear refer to the “two” conventions of the photograph as empirical evidence and the viewer’s imaginative work, but The Past in the Present in SF adds another set of conventions potentially troubled by its presentation of “before-and-after” photographs: the performance of the diasporic subject.

Kondo’s reenactment challenges the appearance of a smiling, casual Miki. Most noticeably, Kondo’s clothing makes his great-grandfather’s suit seem stiff and uncomfortable, especially in the shots of Miki in front of natural landmarks. In Kondo’s first re-creation of Miki’s pose in front of the Conservatory of Flowers, he wears jeans and a hoodie (see again figure 3). Looking at Kondo, Miki, in retrospect, seems much more formal, as if he dressed for the occasion of the photograph. The comparison between the two men, thus, disputes any performed ease in which Miki lived and inquires into his unseen burdens. Further, Kondo does not smile. Unnervingly, his neutral face calls into question our assumptions that Miki’s gleeful expression reflects his life in San Francisco. Kondo’s stare into the camera lens provokes the viewer. His look asks about what we do not see in the family photograph and how its conventions obscure the diasporic subject’s pain or discomfort.

Fig. 7. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 7. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 8. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 8. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.Kondo also disputes his great-grandfather’s apparent belonging when he reenacts group shots (figures 7 and 8). His great-grandfather seems to be a member of a diasporic community, but Kondo’s reenactment creates a different effect, one of awkwardness and separation. Kondo’s lone appearance pulls Miki out of the group, to distinguish him from the other men. By separating his great-grandfather from his community, the video challenges an easy understanding of belonging. The Past in the Present in SF, by contrasting Kondo and Miki, undermines Miki’s appearance; the video casts it as staged, a performance that has meaning only at a surface level. If, on their own, Miki’s happy, successful photographs gesture at the upward mobility of a model minority, Kondo’s reenactment asserts that this ascension cannot be taken at face value.

Recovering the Past through the Family Album

Kondo’s embodiment is one part of The Past in the Present in SF’s performative strategy to reenact the family album. Another is the video’s organization of images. Following Campt, by thinking through the “affective and enunciative functions” of the “seriality” of photographs, the video’s curation can unfold “more complex process[es] of cultural articulation, improvisation, and reiteration.”[25] The collection of photographs in The Past in the Present in SF highlights the workings of the family album as that which preserves and transfers family memories.[26] Kondo acquired the photographs that make up The Past in the Present in SF in his great-grandfather’s effects, stored in a box in his grandmother’s house in Japan.[27] Kondo knew about the photographs when he was a child, but he became interested in them only after living in Berlin for eight years. When he was cleaning hotel rooms, he realized that he was an immigrant, and his felt connection to his great-grandfather prompted him to recover Miki’s belongings from his grandmother. In The Past in the Present in SF, Kondo’s frequent appearances associate him with his great-grandfather and insert him as participant in his family history. Kondo’s replication and curation of the family album reimagines engagement that has been rearticulated through lenses of temporal and spatial separation.

The role of the family album as interactive aide-memoire contextualizes The Past in the Present in SF’s investigation into Miki’s past. As Zuromskis writes, the family album endows meaning to a photograph after the moment of the shot, when the image is compiled into an album for the family.[28] “Constructed as a private text addressed to a private collective of participants who may contribute to its monumental and narrative meanings,” the album is thus dependent on continued discourse.[29] Certainly, many of us have experienced this when we look at an album with our parents and grandparents, learning about important family events and our own life milestones through images and dialogue.

In contrast, Kondo knows little about his great-grandfather’s life. After Miki’s wife returned with her son to Japan, in 1925, he never saw her again — she passed away in 1942. When he returned to Japan, he was with his son, daughter-in-law, and grandson for just two years before his death, in 1956. Kondo’s grandmother has told him certain details about Miki’s life, but she has not been able to answer all of his questions. His 2016 video, “My Grandmother Is Telling about MK,” highlights some of these unanswered questions when Kondo asks her about Miki’s time at Topaz, and she explains that she did not hear about it but wonders if it was difficult for him.

Fig. 9. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 9. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 10. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 10. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.The Past in the Present in SF foregrounds further gaps in Kondo’s knowledge of his family history. Although Miki left behind a remarkable ten albums of photographs, the video presents fewer than ten of his images.[30] Kondo’s selection calls attention to the locations he cannot find. The video frequently features Miki within group shots; Kondo appears alone. He does not stand in for anyone else, and the video never addresses the identities of the others. Elsewhere, The Past in the Present in SF quietly marks what we never see — Miki’s wife, son, or the identity of the photographer(s). Read against Miki’s historical context, The Past in the Present in SF identifies absences created by diaspora: Kondo may be able to find a few of his great-grandfather’s favorite San Francisco locations, but he may not be able to connect with the people in his great-grandfather’s social circle. When the video identifies differences between photographs, it reminds us of the vast temporal distance between the two men. For example, an entire building disappears between a group photograph and Kondo’s visit; Kondo must pose in front of a power station instead of a former dry cleaner (figures 9 and 10).[31] These major differences suggest that there are aspects of his great-grandfather’s past that Kondo simply cannot recover from photographs alone.

These unanswered questions reflect the dearth of surviving material about the Japanese diaspora before internment. The model-minority myth obscures the constitutional injustice of internment, with the years before WWII largely ignored.[32] Even internment leaves limited visual records today, leading Marita Sturken to define the event by its “absent presence”; few censored images remain, making the event, “for the most part, absent from the litany of World War II images that constitute its iconic history.”[33] During forced relocation, the War Relocation Authority limited families to what they could carry. As a result, many Japanese immigrants left behind personal items, among them family photographs.[34] Kondo’s collection of photographs in The Past in the Present in SF locates an important family archive and inserts it into the public sphere. At the same time, the comparatively small number contained in the video seems to suggest our inability to understand or gain meaning from the images, despite the large number, the result of systemic erasure and an irrevocable loss.

The Past in the Present in SF documents Kondo’s efforts at recovery in the face of absent information and dialogue. The number of questions raised throughout, including the identity of the photographer and when the photographs were taken, remain unanswered. As Karen Strassler remind us, without “people who animate them with sentiment and story, photographs remain incomplete objects.”[35] Kondo’s grandmother filled him in on some of the details of his great-grandfather’s life, but he heard little information about Miki’s time in the United States. Instead of dialogue with family members, then, it is possible to consider Kondo’s embodiment and curation of his great-grandfather’s photographs as a reconsideration of how to connect to the family album, one necessitated by the conditions of diaspora. In this way, The Past in the Present in SF adds to Phu, Brown, and Dewali’s assertion that family photographs “provide a valuable resource for writing new histories that are integrally transnational.”[36]

Instead of extended dialogue with or about Miki, Kondo must turn to interacting with the places in the photographs. The video moves around the Bay Area, from Stanford University, in Palo Alto, to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park — sites historically, culturally, and personally significant. By visiting these locations, The Past in the Present in SF activates what remains from Miki’s past, insisting on the importance of Kondo being at the site. When Kondo stands in for Miki, The Past in the Present in SF connects his body across time; for that moment, both men, great-grandfather and great-grandson, share a viewpoint. The Past in the Present in SF documents Kondo’s first visit to San Francisco, and Miki’s photographs introduce him to the city. Kondo’s reenactment becomes a surrogate for the discursive aspects of the family album, with the back and forth between old images and new re-creations as conversations between Kondo and Miki’s photographs.

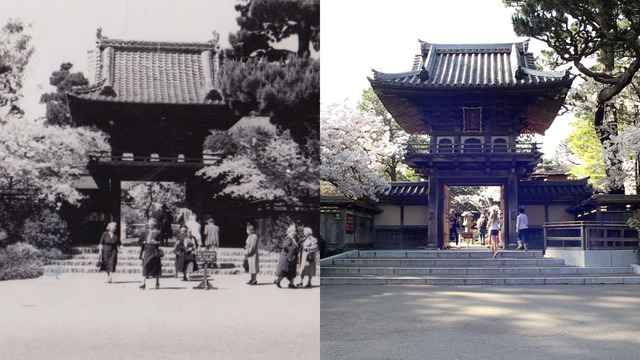

The Past in the Present in SF extends this discursive relationship with its viewer. Miki appears in approximately half of the photographs in the video; the other images are simply of locations. The identity of the photographer in all of Miki’s images is unclear, but these location-only shots were presumably taken by Miki and were significant enough in his life to remain in his possession. When Kondo replicates these images, he places his version next to Miki’s (figure 11). Together, the photographs triangulate dialogue among past, present, and the viewer. The double image of the temple introduces Miki’s perspective to us; it connects us to Miki by showing us what he saw decades ago. In this respect, Kondo takes on the role of the family-album interlocutor, and he identifies replication and display as ways to relay aspects of his family history.

Fig. 11. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 11. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke. Fig. 12. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 12. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.The photographs also illustrate how physical sites express the continued influence of Japanese immigrants. Figure 11 shows a temple replica in Golden Gate Park’s tea garden. Built as part of the Japanese Village exhibit at the California Mid-Winter Exposition in 1894, the tea garden recalls emerging global connections and imperial influence in which immigrants were imbricated.[37] The garden was built by Makoto Hagiwara, a Japanese immigrant who, along with his descendants, maintained it until his own forced relocation and incarceration during the war. The image of both photographs, Miki’s and Kondo’s, prompt nonverbal communication with Miki and Hagiwara. There are multiple layers at play here — Hagiwara built and maintained the tea garden, diversifying Golden Gate Park’s buildings and horticulture. Miki took photographs of this garden to mark its significance in his life, and Kondo replicates it to call attention to its importance for Miki. All shape our understanding of the city as forever altered by the diasporic subject — Japanese immigrants did not just visit locations; they also inhabited and changed them.

When The Past in the Present in SF focuses on Miki’s life in San Francisco before his incarceration, it expands the visual record of the Japanese diaspora. Internment still appears, however, in the video’s penultimate image, of Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066 (figure 12). Kondo has not completely elided internment — it is still part of Miki’s history. It is the reason why he leaves San Francisco. Pitting Roosevelt against the prewar images of Miki, The Past in the Present in SF calls attention to the emphasis on the internment in public discourses, one that ignores the normal, everyday lives of Japanese immigrants before the war. In other words, the Japanese diaspora has been shaped by images of forced relocation and incarceration, images that cast more than one hundred thousand people of Japanese heritage, more than half of whom were American citizens, as inherently “other,” foreign, and always potential enemies of the state.

However, the photograph of Roosevelt and his Executive Order 9066 does not have the final word in Miki’s story. By placing it as the second to last image, Kondo deemphasizes Roosevelt and mass incarceration of Japanese Americans. Instead of framing Miki’s life through wartime relocation and incarceration, The Past in the Present in SF portrays these historical events as an ongoing concern. Roosevelt does not appear alone. Instead, Roosevelt’s photograph is cut in two and inserted into an image of the white house in the present day. In between the two halves of Roosevelt is another Caucasian man at the president’s desk. Although his face is obscured, we can guess that this man is Donald Trump, a gesture toward continued issues of diaspora and anti-immigrant sentiment in the present. With its reference to Trump, The Past in the Present in SF marks the ways in which the past continues in 2017’s xenophobic legislative practices.

Roosevelt’s actions may have ended Miki’s residence in San Francisco, but they did not cause Kondo to leave his familial past behind. Instead, the video’s final image is of Miki in the tea garden (figure 13). The Past in the Present reiterates its connections among family photograph, family history, and location. Kondo does not reenact this pose but leaves his great-grandfather as he was, the photograph in the past inset in a present-day image of the garden. Looking at the camera, Miki is there, a trace of history that endures in the here and now. In the same layout as the video’s opening photograph of Miki in front of Stanford’s Memorial Church, the image of Miki blends into its background. But Miki is also not there — the contrast between his image, in black and white, and his background, in color, reminds us that he has long since departed the city.

Fig. 13. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.

Fig. 13. Still from Kondo, Aisuke, The Past in the Present in SF, 2017, 6:32 minutes, video, © Kondo Aisuke, courtesy of Kondo Aisuke.Given Miki’s wartime experiences of forced relocation and incarceration, his smile reflects the complexities of performance and place in which the diasporic subject is embedded. Preceded by that of Roosevelt, this final image reiterates questions of Miki’s belonging and recasts his pictures as travel photographs. In this case, Miki’s poses become ways to document his stay in the Bay Area, almost presupposing his eventual departure for Japan. In part, The Past in the Present in SF illustrates that the diasporic subject always occupies a temporary space, one of never being grounded, always a visitor even though, like Miki, he may reside in a country for decades. On the other hand, Miki’s smile, after the picture of Roosevelt, can be read as resilience, one that challenges his positioning as other, one that builds a content life despite anti-immigration legislation. With so much information missing from Miki’s past, however, we can only gesture at hypothesis. His gaze wraps us in a silent exchange and leaves us with what we can only attempt to understand, but what ultimately we cannot know.

Conclusion

When The Past in the Present in SF portrays family photography as performative, the video simultaneously illustrates the importance of the act of photography and explores the ways in which mass migration and displacement affect it. For the diasporic subject, Miki, his photographs perform belonging in his new life and community in San Francisco. When Kondo challenges this belonging by replicating Miki’s images, The Past in the Present in SF contemplates the family photograph as that which is altered by the conditions of diaspora. In parallel, the video portrays the effects of diaspora on the family album’s circulation of personal histories. With gaps in information caused by temporal and spatial distance, Kondo’s reenactment of his great-grandfather’s photographs articulates engagement with the past through embodiment and replication. In the end, The Past in the Present in SF stages how Kondo’s experience in the present shapes the family album to suggest that his diasporic family album is dependent on recovery, an undertaking in the present and to be continued in the future.[38] In so doing, the video illustrates the importance not only of family photography, but also of interacting with family photography, even if such interactions require unique approaches.

Jessica Nakamura is an assistant professor of theater at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is working on a manuscript about performances of memories of the Asia Pacific War in contemporary Japan (1989–present).

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers and Deepali Dewan for their generous feedback.

As the ethnic studies scholar Wesley Uenten asserts, Kondo’s life “resonates with the common experiences of diasporic separation.” Diaspora Memoria, exhibition catalogue (Berlin: Kommunale Galerie, 2018), np.

See Kondo’s website for a list of recent exhibitions in Japan, Germany, and the United States (http://aisukekondo.com/Home.html).

Uenten notes that it is unclear whether Miki sent for Kurihara; they were married in 1919.

The very term “internment camp” reveals practices of obfuscation. Writes Joshua Chambers-Letson: “Performative acts of naming and reclassification were central to the government’s execution of the president’s order.” A Race So Different (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 101. Temporary holding sites were called “Civilian Assembly Centers” and instead of “concentration camps,” officials used “internment camps” to refer to long-term facilities. Chambers-Letson notes that “euphemistic renaming . . . continues into the present, when the camps are commonly referred to with the less violent language of ‘internment’” (101). In this article, I use “internment” to refer to the historical event, particularly Roosevelt’s executive order, and “forced relocation and incarceration” in all other instances.

For a discussion of the origins of the Japanese diaspora in the mid-nineteenth century, see Roger Daniels, “The Japanese Diaspora in the New World,” in Japanese Diasporas: Unsung Pasts, Conflicting Presents, and Uncertain Future (New York: Routledge, 2006): 30–34. Despite the ubiquity of the term, resulting in what Rogers Brubaker calls a “‘diaspora’ diaspora,” Nobuko Adachi explains that the examination of Japanese diasporas can diversify the make-up of diasporic communities, along with “notions of home, homeland, and host countries.” I refer to the “Japanese diaspora” to discuss the immigration of Japanese to the United States mainland, but Wolfram Manzenreiter reminds us that the Japanese diaspora extends from Canada to Brazil. Rogers Brubaker, “The ‘Diaspora’ Diaspora,” in Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28.1 (2005): 1–19; Nobuko Adachi, “Introduction,” in Nobuko Adachi, ed., Japanese Diasporas: 1–22; 21; Wolfram Manzernreiter, “Squared Diaspora: Representations of the Japanese Diaspora across Time and Space,” in Contemporary Japan, 29.2 (2017): 106–16.

Thy Phu, Elspeth Brown, and Deepali Dewan, “The Family Camera Network,” in Photography and Culture 10.2 (2017): 147–63; and Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 48.

Thy Phu characterizes the family photograph as that which can “refocus discussion of war and its aftermath. See “Diasporic Vietnamese Family Photographs, Orphan Images, and the Art of Recollection,” in Trans Asia Photography Review 5.1 (2014). Along similar lines, images of Kondo’s great-grandfather shift the discussion of Japanese diaspora from a history defined by internment to an earlier history of establishment in the United States.

Photographic technology was imported in the mid-nineteenth century and quickly became popular, reflecting Westernization efforts in Japan at the time. See Kinoshita Naoyuki, “The Early Years of Japanese Photography,” in The History of Japanese Photography, Anne Wilkes Tucker, Dana Friis-Hansen, Kaneko Ryichi, Takeba Joe, eds. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 14–35. Karen Fraser argues that it is “virtually impossible to define the broad and varied world of Japanese photography by a specific and limited set of visual or nationalistic characteristics. See Photography and Japan (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 8–9. Fraser further puts the history of photography in Japan in parallel with the history of the country’s modernization and Westernization in the nineteenth century.

Dennis Reed, Japanese Photography in America, 1920–1940 (Los Angeles: Doizaki Gallery, 1986), 13–17.

Thy Phu. Picturing Model Citizens (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011, 22. Creef writes that the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the office in charge of internment, closely monitored images of relocation and camp life, prohibiting internees to bring cameras with them. Elena Tajima Creef, Imagining Japanese America (New York: New York University Press), 2004. In her first chapter, Creef analyzes Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and Toyo Miyatake’s photographs of relocation and incarceration.

In two subsequent works in the Matter and Memory series, Santa Anita (2017) and here where you stood (2017), Kondo follows Miki’s same journey of forced relocation to the Santa Anita racetrack and to the former site of the Topaz War Relocation Center.

Catherine Zuromskis, Snapshot Photographer: The Lives of Images (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 65.

Strassler also describes this role in viewing photographs: “training people to see in particular ways and in working to entwine personal experiences with larger historical trajectories” can “bind people to broader collectivities and social imaginaries.” Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 3.

Anthony Lee, “Introduction” to Trans Asia Photography Review special issue 5.1 (2014).

Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” in Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, eds., Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader (London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1994), 227–37; 235.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 prohibited nonwhite immigrants from gaining citizenship. See Chambers-Letson for a discussion on the “performativity of the law” used “to reshape Japanese American civic subjectivity” in Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 (99). Chamber-Letson asserts that “the force of the order was bolstered by two centuries of preceding legislation and case law which included the bar to citizenship eligibility” for first-generation immigrants like Miki, “defined in the Naturalization Act of 1790,” 100.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 87.

Japanese Americans are identified as the exemplary model-minority group, and their experiences of hardship, notably internment, contribute to their ability to succeed in the face of oppression. David Palumbo-Liu, Asia/American (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 174–75.

As Palumbo-Liu writes: “In short, the model minority myth provided the opportunity for conservatives to situate the causes of these problems outside a consideration of institutional racism and economic violence: the success of the Japanese Americans was used to dispute a structural critique of the U.S. political economy.” David Palumbo-Liu, Asia/American, 172.

Kate Palmer Albers and Jordan Bear, “Photography’s Time Zones,” in Before-and-After Photography, Jordan Bear and Kate Palmer Albers, eds. (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 1–11; 2.

Kuhn describes the connection between family photographs and memory: they have “considerable cultural significance, both as repositories of memory and as occasions for performances of memory.” Annette Kuhn, “Photography and Cultural Memory: A Methodological Exploration,” in Visual Studies, 22. 3 (2007), 283–92, 284.

Ibid., 57. Of course, there are other elements that factor into the curation of the family album, among them an editing process, whereby less photogenic but more “historically accurate” traces are deliberately eliminated (Zuromskis, 55).

According to Kondo, these albums contained photographs with family, friends, and colleagues; self-portraits; and travel images. Personal communication, August 2018.

Kondo guesses at this location and the men in the photograph. Personal communication, May 2018.

Yuji Ichioka, Before Internment: Essays in Prewar Japanese American History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 3.

Marita Sturken, “Absent Images of Memory,” in T. Fujitani, Geoffrey White, and Lisa Yoneyama, eds., Perilous Memories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 36–38.

Reed mentions that even the more artsy pictorial photographs were lost during forced relocation (13). Creef discusses the attempts of the federal government “to control the wartime representation of the Japanese American internment camps through a campaign of visual censorship,” Imagining Japanese America, 17.

See Kendall Brown, “Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940,” in SiteLINES: A Journal of Place. 4.1 (2008): 13–16. These gardens “served as an opportunity for Japan to export desired aesthetic and cultural values,” functioning, in essence, as “ideological tools” (14).

Kondo will travel to San Francisco again in late 2018 to continue the work of tracing his great-grandfather’s past.