Masaki Yamamoto, Guts

ISBN 978-4905453567

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In the twentieth century, the American ethologist John B. Calhoun used rodents to study the relationship between population density and human behavior. A particularly famous experiment involved confining rats within a small space, which allowed them to reproduce rapidly. Among the memorably lurid consequences were violent aggression, cannibalism, offspring mortality, and social withdrawal. Calhoun’s research documented the grim facets of overpopulation, revealing the frenetic devolution of rodent behavior within claustrophobic quarters. With human implications in mind, Calhoun aimed to investigate the short- and long-term consequences of population density and how spatial congestion might cause certain social pathologies. Calhoun’s observations culminated in what he termed “behavior sink,” or the collapse of animal behavior within overcrowded spaces. Collapse of rodent social order, Calhoun concluded, precipitated a kind of “spiritual death.” Calhoun’s research and larger concerns of human overpopulation captured the twentieth-century American imagination, elucidating the realities of how certain life-forms respond to cramped conditions — and how space, or enough of it, plays a role in preserving social order.

In the Japanese photographer Masaki Yamamoto’s arresting collection, Guts, Calhoun’s anxieties of spiritual death couldn’t be more remote from the realm of human experience. Yamamoto exhibits ninety-two spectacularly blunt black-and-white photographs of his seven-member family during their cluttered, eighteen-year tenancy in a one-room apartment in Japan. His dim and granular images comprise an album documenting domestic life among serried heaps of laundry, dishes, and newspapers, as his family members eat, bathe and sleep, laugh and play games, work and celebrate the New Year. Since the publication of Guts, the family has saved enough money to rent a home, though in the afterword to the collection Yamamoto bids a farewell that is hardly gleeful to the “small and dirty” apartment. Instead, he draws an unexpected connection between the shared experiences of cramped tenancy and familial unity, reflecting: “I have come to realize that this is my origin and where I will always return to.” Yamamoto understands that the family’s experience in the tiny space cemented sibling and parental relationships in important ways. Yamamoto, the afterword recounts, isn’t alone in feeling emotionally indebted to the cramped apartment: His mother posted many of the images featured in Guts on the bathroom walls of the new home “in order to not forget about the spirit of the Yamamoto family.”

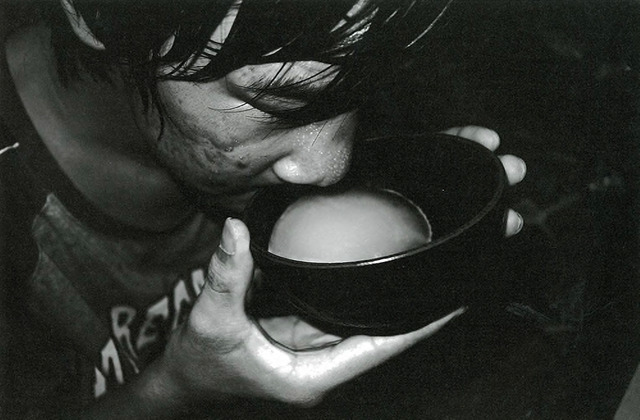

Fig. 1. Yamamoto, Masaki, “There are always tons of dishes to be washed in the sink. My little brother was drinking calpis soda with a bowl as there were no more cups available.” (From Guts, 2017.)

Fig. 1. Yamamoto, Masaki, “There are always tons of dishes to be washed in the sink. My little brother was drinking calpis soda with a bowl as there were no more cups available.” (From Guts, 2017.)Yamamoto’s mother performs an act of preservation that situates Guts within the unexpected genre of the family photo album, albeit one that is wonderfully heterodox. As a kind of unconventional family album, Guts functions as a portal of communication and memory, similar to the type described by the visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards, who defines family photographs as highly interactive “performative objects” that evoke and create memory, history, and emotion. As performative objects, she says, photographs shape existing memories and create new ones through the emotions and recollections they conjure in viewers. Their circulation and consumption (that is, viewing) shape memory, the perception of past events, individual and collective memory, and the relationships one has with the subjects photographed.

Indeed, as Edwards writes, “Objects, including photographs, are therefore not just stage settings for human actions and meanings, but integral to them.” Yamamoto’s collection amounts to more than a set of thematically related images; rather, as a kind of family album, it creates meaning by transcribing the family’s lived experiences into photographic records of parental and sibling relationships, living conditions, and memorable family moments — events and phenomena that transcend human movement across physical spaces.

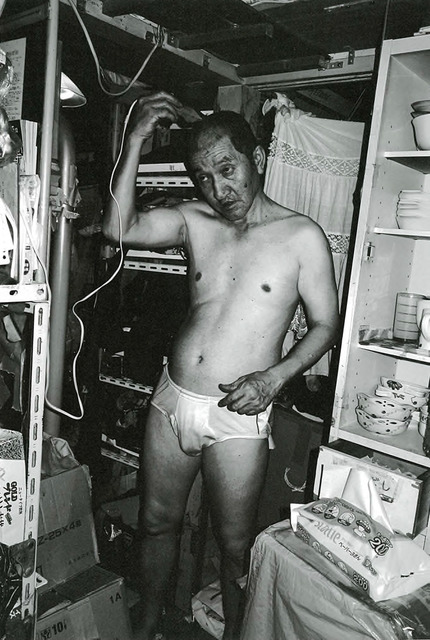

Significantly, Yamamoto’s mother assigned the photographs an interactive role when she hung them in the new bathroom, as they served not only to stir recollection but also to shape memory in a way that further cemented family unity. Yamamoto’s album continues the task of using the photographs to shape family memory from a variety of angles, one of which is humor. For Yamamoto, humor functions more as a lens for revealing the individual textures of family personality and relationships than as a means to provoke laughter. In one image, Yamamoto’s mother prays; at her back sits his younger sister, who picks her nose insouciantly. Another depicts a silly close-up of his mother and younger brother, their eyes clenched shut, laughing hysterically. Yamamoto’s humor is occasionally unexpected, and viewers will be uncertain at times if they should laugh. For example, one image depicts his ageing father, wearing only stained underwear, who concentrates on the task of shaving his head — if not hilarious, the image catches his father in a moment of goofy simplicity. Some images are posed, others are spontaneous; however, Yamamoto’s sense of humor draws out the idiosyncratic personalities of his parents and siblings, as if to dispel assumptions that the family’s spirit is proportionate to the size of the apartment.

Fig. 2. Yamamoto, Masaki, “Since my father shaves his head at the kitchen, all his hair always falls to the floor which would sting our feet.” (From Guts, 2017.)

Fig. 2. Yamamoto, Masaki, “Since my father shaves his head at the kitchen, all his hair always falls to the floor which would sting our feet.” (From Guts, 2017.)In Guts, humor serves to animate one of Yamamoto’s central artistic achievements, which is his ability to challenge viewers’ assumptions about the photographic content they will encounter. Approaching this particular collection, viewers likely expect dismal images that portray Yamamoto’s poor family members sitting dejectedly amid their world of clutter, stagnate in self-pity and domestic ennui. Neither dysfunction nor malaise, peculiarly enough, exists in this album, and though many of the images expose the confining poverty of the Yamamoto family, his subjects are photographed in outbursts of laugher, relishing meals, and dancing, their moods at striking odds with their claustrophobic world.

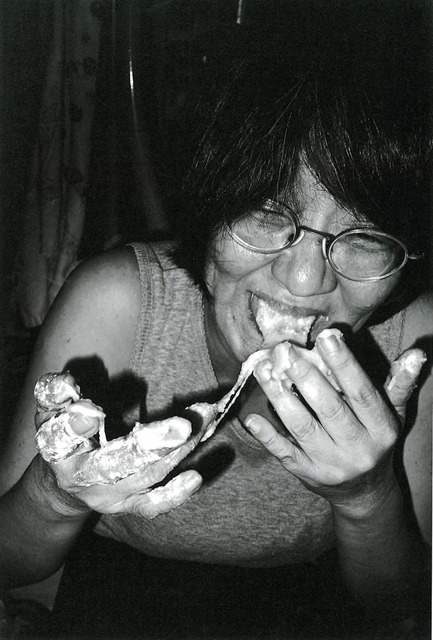

Fig. 3. Yamamoto, Masaki, “My mother licking her hands stuck with sticky rice as she couldn’t make the rice-cakes properly.” (From Guts, 2017.)

Fig. 3. Yamamoto, Masaki, “My mother licking her hands stuck with sticky rice as she couldn’t make the rice-cakes properly.” (From Guts, 2017.)As a kind of performative object that preserves memory, Guts eschews certain recognizable tropes of the conventional family photo album — there is no staged group portraiture or snapshot of a family vacation, no beloved pets or newborn children. Instead, Yamamoto seems to be interested in documenting family dynamics when conventional demarcations of private-communal space becomes increasingly porous or, in the unusual environment of the cramped one-room apartment, cease to exist entirely. His album is punctuated regularly by photographs portraying the otherwise cloistered routines of domesticity; importantly, these images likely derive from Yamamoto’s impulse to express the unadorned realisms of family life rather than deliver shock-factor content.

Indeed, he does not wince at family nudity or the intimacies of self-care, turning the camera on his younger brother defecating; his mother emerging naked from the shower; even his father, bent on all fours, dabbing talcum powder on his anus. Photographing his younger sisters, Yamamoto peers gently into their intimacies, too, as they daydream, sleep, and change clothes. In one beautiful portrait, Yamamoto’s teenage sister bathes in a tub of cloudy water with her knees tucked under her chin, her head averted uncertainly from the lens. Yamamoto’s Japanese-English caption provides the context: “My younger sister puts her knees up so that it would look like she had big breasts.”

Although these images suggest no unnerving voyeurism, they raise questions about sexuality and the unusual privileges enjoyed by Yamamoto’s camera in the absence of privacy, especially as he photographs younger (including pubescent) siblings as they bathe, use the toilet, and change their clothes. Among the questions these images raise is how the exploration of sexuality is interrupted or deferred due to the lack of privacy, and whether living in a privacy-deprived home has an adverse impact on experiences of puberty. Meanwhile, as a young woman, does Yamamoto’s sister consent to being photographed or is she passively accepting the regularity of her older brother’s intrusions? And who affixed the caption to the photograph of Yamamoto’s bathing sister? Is it a teasing description or a genuine bodily anxiety expressed by his sister? As these questions go unanswered, Yamamoto seems to take advantage of a domestic world without privacy, barging in on family who might be trying to retain what fragile forms of it can be salvaged in a one-bedroom apartment.

Viewers who might balk at Yamamoto’s seemingly invasive lens should consider that these images demonstrate, in part, a fidelity to realism, to convey the blunt realities of family life that privacy largely obscures. In a recent interview, Yamamoto elaborates: “Sometimes I may capture the most intimate moments or what I am attracted to, but if you ask me what my goal is, I would say I want to capture the ‘ecology’ of my family, how the members are related with each other, how they interact with each other, and how they live together in the environment. By doing so, I could rediscover the way my family is and understand them better.” In this way, Yamamoto is pulled directly into orbits of intimacy with each family member that an absence of privacy affords.

Yamamoto records his domestic world with candid spontaneity and a distaste for affectation, producing a collection without sentimentalized and saintly depictions of family life. For all of the collection’s poignant unconventionalities, though, there is a slight hagiographical quality. His photographs almost always capture his family in moments of laugher, unity, and blithe goofiness — and although it was mentioned earlier that one of Yamamoto’s artistic strengths is his ability to undermine viewer expectations (that is, not depicting family misery), it seems reasonable that a full photographic study of so-called family ecology would embrace the occasions of weariness and disappointment brought on by economic hardship. But even if Guts is at times unbalanced emotionally, it is an uplifting photographic narrative of a family whose love and sense of humor transcend poverty.

Sebastian C. Galbo is a co-editor for the New York University School of Medicine's Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database (LitMed). His reviews and articles have appeared in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, Lit Med Magazine, and Transnational Literature, and are forthcoming in Callaloo and SX Salon | Small Axe Project.

Works Cited

- Calhoun, John B. “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population,” in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 66.1 Pt. 2 (1973): 80–88. Print.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

- Sng, Oliver, et al. “Does Living in Crowded Places Drive People Crazy?” in Scientific American Blog Network, 14 February 2017, blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/does-living-in-crowded-places-drive-people-crazy/.editmore horizontal

- Yamamoto, Masaki. “Capturing the Ecology: An Interview with Masaki Yamamoto.” Interviewed by Julian Lucas and Kathleen Graulty, in Mirrored Society, 12 August 2018. https://mirroredsociety.com/interview/guts-masaki-yamamoto