Following the Box: Exploring an Archive of Anonymous Photographs from India

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Fig. 1. Photographer unknown, Indian Woman, #909, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 1. Photographer unknown, Indian Woman, #909, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 2. Photographer unknown, Indian Man, #1174, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 2. Photographer unknown, Indian Man, #1174, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 3. Photographer unknown, Temple Shot-Hindu, #1206, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

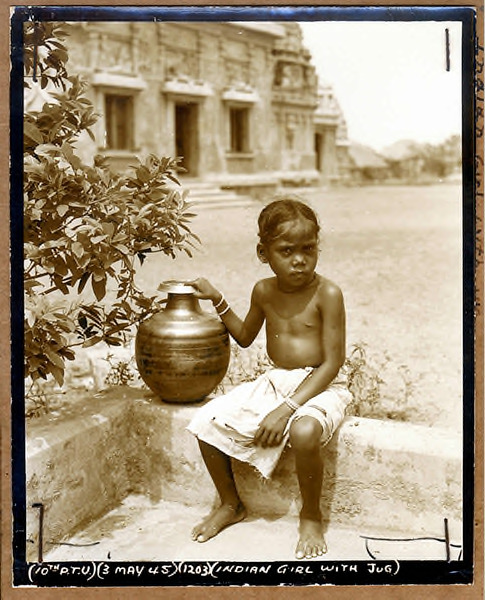

Fig. 3. Photographer unknown, Temple Shot-Hindu, #1206, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 4. Photographer unknown, Indian Girl with Jug, #1203, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 4. Photographer unknown, Indian Girl with Jug, #1203, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 5. Photographer unknown, Fisherman, #1188, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 5. Photographer unknown, Fisherman, #1188, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 6. Photographer unknown, Indian Operating Forge, #905, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 6. Photographer unknown, Indian Operating Forge, #905, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 7. Photographer unknown, Beetlenut Series, #1240, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

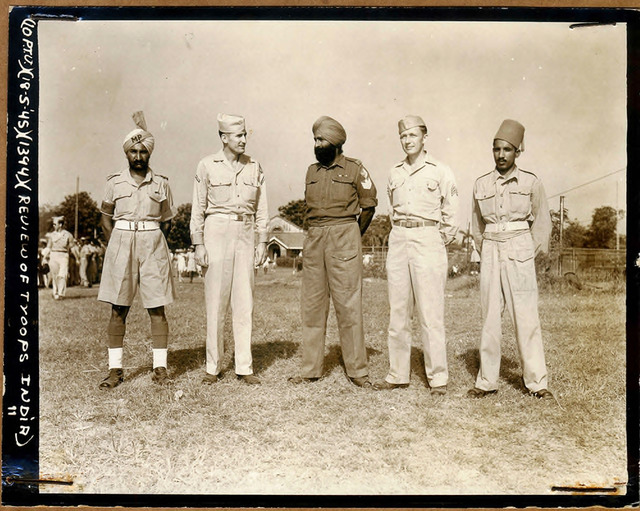

Fig. 7. Photographer unknown, Beetlenut Series, #1240, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral. Fig. 8. Photographer unknown, Review of Troops India, #1344, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.

Fig. 8. Photographer unknown, Review of Troops India, #1344, 10th PTU series, 1945, 4x5”, gelatin silver print, courtesy of Alan Teller & Jerri Zbiral.INTRODUCTION

Following the Box is a mystery, a film and art exhibit, and a visual dialogue between photographers and artists from the United States and India over time. It is based on our chance discovery of a box of photographs and 4x5-inch negatives at an estate sale near Chicago. Dated 1945, the striking portraits and images of temples, village life, and military scenes were made by an unknown U.S. soldier stationed in West Bengal. Initially funded by a Fulbright-Nehru grant, the project addresses the question of who took the photos and for what purpose (with no clear answers) but adds another dimension: It explores how historical images can inspire the creation of new art. Ten prominent Indian artists in varying disciplines (painting, photography, film, mixed-media, graphic arts, graphic novel, folk art) participated, as did we. All of us responded to the old photos in our own way, informed both by our personal artistic sensibilities and by the cultural nets that envelop us all.

We also created a documentary film entitled Following the Box, which premiered at the New York Indian Film Festival in 2015 and has now been shown internationally. A three-thousand-square-foot exhibit of both the historic work and the contemporary art it inspired will be on display at the Loyola University Museum of Art, in Chicago, from July 6 through October 13, 2018. The exhibit has already been shown at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, in Kolkata, and the Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, in Delhi, the latter courtesy of a U.S. State Department grant.

Research indicates that a U.S. soldier stationed at the Salua airfield, a once secret American base near Kharagpur, India, made the original photographs. He was associated with the 10th Photographic Technical Unit of the XX Bomber Command, which operated in the China-Burma-India theater during World War II. From 1942 to 1945, the unit was preparing for a possible invasion of Japan; with the end of the war in Europe and the decision to drop the atomic bomb, the unit was dissolved. May 1945 was a transitional month, when the men were waiting to be reassigned. It seems likely that this collection of images was made then as a personal project by one of the unit's reconnaissance photographers.

Striking in these images is the lack of a “colonial gaze,” or objectifying portrayal. There appears to be a rapport between photographer and subject, rare for the time — and acknowledged by all of the participating Indian artists. This is particularly unusual, as Bengal in 1945 was the center of an often-violent independence movement led by Nataji Subhas Chandra Bose, an opponent of Gandhi and Nehru who famously said, “Freedom is not given, it is taken.” Even though the American soldier-photographer often used simple captions such as “Indian Man” and “Indian Woman and Child” with no indication of individual identity, it seems that he was seen as different from his colonial-British counterparts.

This curatorial selection focuses on six Indian artists’ visual responses to the American photographer’s images. (The full Following the Box project also includes artwork by Sunandini Banerjee, Aditya Basak, Swarna Chitrakar, Sarbajit Sen, and ourselves.) The statements we present were written by each artist and accompany their work in the exhibit. The work of each is prefaced by a short description of the artist’s installation.

AMRITAH SEN

Curators’ note: Amritah paired a series of the found images with ones from her family album, then tied the images together in a handmade, fold-out book illustrated with their cultural and historical context.

The box of unidentified photographs brought by Alan and Jerri instantly reminded me

of viewpoints.

The little information available was that an unknown American soldier took these photographs during the Second World War, somewhere in rural Bengal. Not knowing all the details we now know, I wondered about how things change with the viewpoint.

These pictures immediately reminded me of my family album, restored with care and love by my parents. Pictures from the same time period are plentiful — the childhood days of my father and aunts, studying in convent schools, having a happy and carefree life, oblivious about many things happening at that time that are now considered important in history.

There is a sharp contrast in the flow of life captured by the American soldier in 1940s Bengal and what a middle-class urban family portrayed.

I decided to make an album showing this contrast. I chose ten portraits and group photographs from the box and ten similar snaps from my family album of the early 1940s, which surprisingly have a certain kind of compositional affinity to each other. The difference between them was clear and distinct. As a third layer of the narrative, I picked up four of the most important and hair-raising incidents of that time from the political history of Bengal. They were: the Bengal Famine; the Japanese bombing over Calcutta; the INA (Indian National Army) activity and the death of Subhas Chandra Bose in Southeast Asia; and the horrific communal riot of 1946. It shows how the same time continues to live in different formats simultaneously, oblivious to what is happening, in what someone might call the “official history.”

The accordion-format album has no beginning or end as such. Like time, the story flows from one to another and then comes back in a circle.

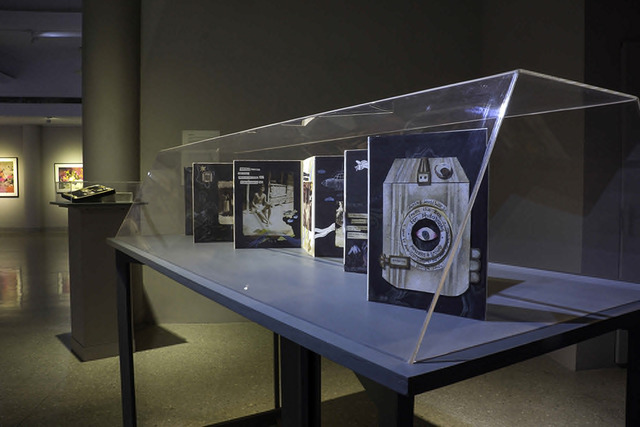

Fig. 9. Sen, Amritah, Following the Box, overview of installation, 2015, 12x9” extended to 109”, hand-constructed book with hand-made paper; ink, watercolor and tea stains, eleven double-sided accordion pages, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 9. Sen, Amritah, Following the Box, overview of installation, 2015, 12x9” extended to 109”, hand-constructed book with hand-made paper; ink, watercolor and tea stains, eleven double-sided accordion pages, courtesy of the artist.SANJEET CHOWDHURY

Curators’ note: Sanjeet crafted a short film in the form of a letter written by the unknown photographer to his fiancée back in the States. The artist imagined that the GI was Jewish, adding yet another interpretive layer to his work. He also created a series of accompanying photos based on a toy model-B29 airplane.

Looking at the found photographs and having an interest and some knowledge of that time, I assumed that the unknown soldier/photographer must have been part of a B29 crew. Research by the curators identified Kharagpur as the likely air base from where he operated. With the photos in hand, I constructed a short fiction video, Letters To Rachel, a poignant story of love and longing, memory and culture told through letters and photographs taken by our unknown soldier toward the end of WWII to his imagined/real girlfriend back home in Baltimore. In this six-and-a-half-minute video, the old photos become a springboard for storytelling.

Letters to Rachel deals with an outsider seeing India and trying to understand the culture, the space, the people. Look at the way he sees his subjects and their environment — there is a humanness to it. It is neither seeing the world through rose-colored glasses, the West’s romanticizing the East, nor is it colonialism. These photos reveal a person trying to understand, a photographer with perspective. I have tried to put myself in his shoes, to imagine what he might have seen and thought seventy years ago.

Being a photographer myself, I also wanted to create a series of still images to add to the film. I visualized the aircraft, but didn’t know how to put it in the context of this project. After going through the photos again and again and reading about the operation, the images slowly emerged. Now I saw the journey of the aircraft and the man: the flight path of the aircraft, traveling over/along the mountains; the man with the camera; the photographer and his photos.

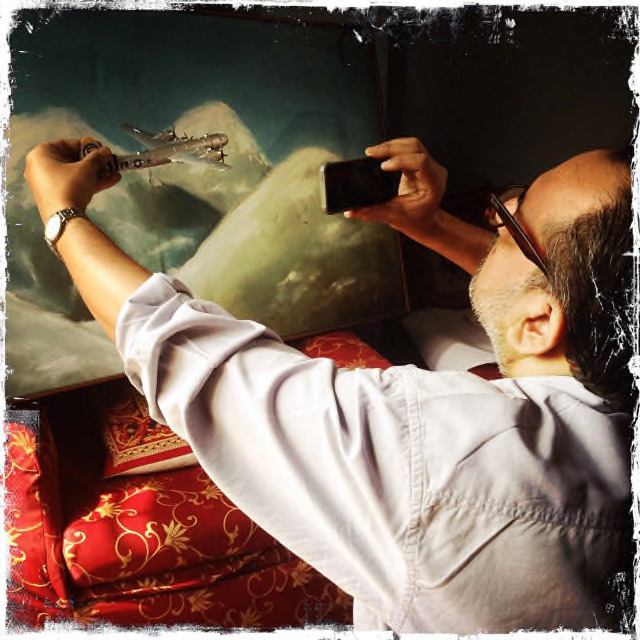

I decided to create three scenarios using a plastic model-B29 airplane. For the first, I used an old painting of the Himalayas done in a very amateurish way as a backdrop. For the second, I used the airplane model in juxtaposition with an old wooden glass-plate camera to symbolize photography (this camera model was not the one used by the photographer). For the third, I set the 1945 photos as a backdrop for the model, as if we were seeing patches of land in Bengal when viewed from an aircraft. The format of the photographs, as well as their being black and white, denote a time and stir a collective memory in us. I used an iPhone 5c to shoot the images with an app approximating the feel of an old photograph.

Fig. 13. Teller, Alan, Sanjeet Chowdhury creating his airplane image, 2015, 6x6”, digital image using Hipstamatic iPhone program, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 13. Teller, Alan, Sanjeet Chowdhury creating his airplane image, 2015, 6x6”, digital image using Hipstamatic iPhone program, courtesy of the artist. Fig. 14. Chowdhury, Sanjeet, #2, from B-29 series, ed. of 11, 2015, 8x8”, digital print on archival paper, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 14. Chowdhury, Sanjeet, #2, from B-29 series, ed. of 11, 2015, 8x8”, digital print on archival paper, courtesy of the artist. Fig. 15. Chowdhury, Sanjeet, #1, from B-29 series, ed. of 11, 2015, 8x8”, digital print on archival paper, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 15. Chowdhury, Sanjeet, #1, from B-29 series, ed. of 11, 2015, 8x8”, digital print on archival paper, courtesy of the artist.Sample frames and audio (text) from video:

MAMATA BASAK

Curators’ note: Mamata took a selection of images and presented them in the manner of traditional scroll painting. She then wrote on each image in the imagined soldier/photographer’s voice, expressing his feelings at what he was witnessing around him, specifically as it related to the war.

These photographs, from the year 1945, weren’t recovered until recent times. A soldier coming from the far land of the United States had deftly captured our village life in his small machine, long before our birth.

The images leave me with a queer feeling. The scenes, though not unfamiliar, have a conspicuous feel of that period. The crowded markets cast a mingled sense of rural and urban life. I do not know how the American soldier perceived our Bengal, but the selection of images indicates that he took a very keen interest in the lives and society of the Bengalis at the time.

I have represented these pictures by placing them in a framework of Mughal miniature paintings. I have even juxtaposed different motifs and pictures with the photographs in an attempt to make the artwork more contemporary. The old and the new have been knitted together through the use of the scroll method, which comes from the ancient Bengali-village culture.

Fig. 17. Basak, Mamata, Untitled, 2015, 56x18”, two digitally collaged scrolls, print on canvas with hand painting and lettering, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 17. Basak, Mamata, Untitled, 2015, 56x18”, two digitally collaged scrolls, print on canvas with hand painting and lettering, courtesy of the artist.CHHATRAPATI DUTTA

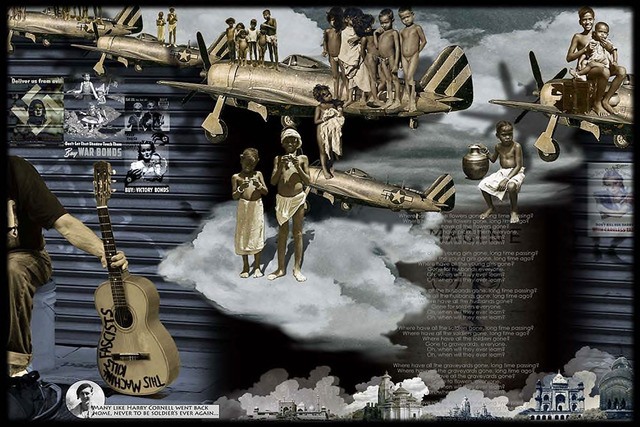

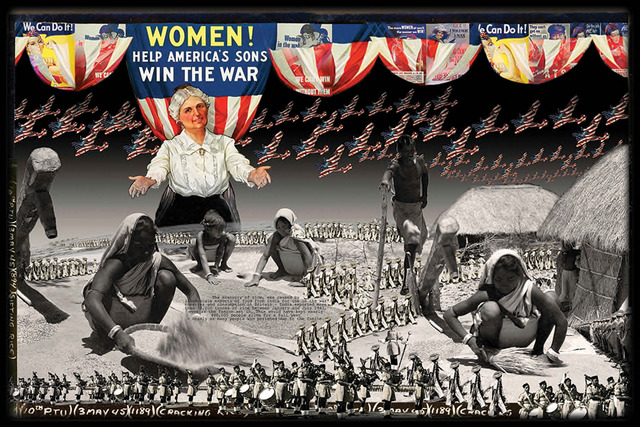

Curators’ note: Chhatra created six lightboxes, each with montaged images from the WWII archive, period posters, and other images. The installation also contained decals satirizing Churchill; images of village people drawn directly on the wall; and twenty-five die-cut acrylic airplanes with LED lights.

Photographs bring back memories, known and learnt; but the FTB prints let one indulge into speculation and imagination. Trying to put in place a logical string of events that justifies the American GI’s lensing of Bengal and beyond up to Okinawa — a soldier him/herself caught in the India-Burma theater — fact and fiction begin to overlap. A new story emerges.

At one level, trying to re-create the impact of the memories of childhood readings of American war comics (featuring the “heroic soldier out there at the front” giving it to the enemy) — the notion of which now stands transposed and further layered with time where wars are games played by people in power — and the real soldier/s here who connects with a strange land through his camera— beyond the moral and psychological tutoring of the army ‘code,’ on the other, become vantage points of evolving narratives.

Possibly unknown to the GI and unspoken by the Empire, all signs of one of the worst human-made holocausts presumably disappear in the FTB photos. The 1943 famine of Bengal — which claimed the lives of four million people remains shadowed but not forgotten nor forgiven — becomes an important part of the layering.

American Propaganda Posters, excerpts from The Calcutta Key*, found photographs of the mid-’40s, and the FTB prints are selectively used to dialectically explore two worlds encountering each other at a time of war.

* The Calcutta Key is a guide–cum–do’s-and-don’ts–manual that was handed over to every US soldier on arrival, marked: For Use of Military Personnel Only. Importantly, the text of the Key was “[p]repared by SERVICES OF SUPPLY BASE SECTION TWO. INFORMATION AND EDUCATION BRANCH. UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES IN INDIA-BURMA” which also mentioned that the “publication is not approved for mailing home.”

Fig. 19. Dutta, Chhatrapati, #5, from Box with No Boundaries series, 2015, 30x20”, computer graphics, acrylic sheet, vinyl print, light and serigraph on glass light box, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 19. Dutta, Chhatrapati, #5, from Box with No Boundaries series, 2015, 30x20”, computer graphics, acrylic sheet, vinyl print, light and serigraph on glass light box, courtesy of the artist. Fig. 20. Dutta, Chhatrapati, #1, from Box with No Boundaries series, 2015, 30x20”, computer graphics, acrylic sheet, vinyl print, light and serigraph on glass light box, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 20. Dutta, Chhatrapati, #1, from Box with No Boundaries series, 2015, 30x20”, computer graphics, acrylic sheet, vinyl print, light and serigraph on glass light box, courtesy of the artist.ALAKANADA NAG

Curators’ note: Alakananda created an installation based on her observation that the date inscribed on the majority of the found negatives was the only “factual” information we could read off the images. She began a search for someone born on that date and was ultimately contacted by the daughter of Subrata Banerjee, who put her in touch with her father. He provided archival materials collected over a lifetime that she then used in her installation.

This work is a disjointed and connected set of images, letters, objects, and audio recordings that try to make sense of the countless number of events that might have happened on May 3, 1945.

I have chosen to work on just one of the many possibilities — that of someone being born on the exact same day as the photographs were taken or presumably when the negatives were processed and the images came to life. This thought was followed by a hunt that was by no means easy. Finally, someone contacted me through a classified ad that I had anonymously put out in a local Bengali daily.

I have used the seemingly insignificant annotated date to walk into someone’s life, then document, research, and fragment it without any distinct beginning or end, past or present, albeit with its ambiguities and complexities. Having been trained as a documentary photographer, my work is steeped deeply in research and fact finding. Over time, however, I have moved away from documenting per se to lean toward a more abstract, less concrete form.

The result is a constructed narrative of Subrata Banerjee’s life — an erstwhile bank employee, umpire, and an avid archivist of his own life. Some things we know; the rest is left to the imagination. In effect, what is presented is a certain quasi reality of Banerjee’s life.

The viewer walks into what seems like a darkroom, which, in a sense, gives birth to the story of Banerjee, and constructs an abstract chronicle just like it did with the photographs back in 1945. The viewer is taken into a space far removed from Banerjee’s life and closer to the set of originals, straddling between dated and recent photographs, objects, certificates, letters, radio recordings, imagined and obvious reality. What the viewer makes of it is what remains. Giving birth to innumerable possibilities.

Fig. 21. Nag, Alakananda, May 3, 1945, detail of multi-media installation, 2015, 10x15’, inkjet prints, artifacts (bottles, trays, books); red lights; audio, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 21. Nag, Alakananda, May 3, 1945, detail of multi-media installation, 2015, 10x15’, inkjet prints, artifacts (bottles, trays, books); red lights; audio, courtesy of the artist. Fig. 22. Nag, Alakananda, May 3, 1945, detail of multi-media installation, 2015, 10x15’, inkjet prints, artifacts (bottles, trays, books); red lights; audio courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 22. Nag, Alakananda, May 3, 1945, detail of multi-media installation, 2015, 10x15’, inkjet prints, artifacts (bottles, trays, books); red lights; audio courtesy of the artist.PRABIR PURKAYASTHA

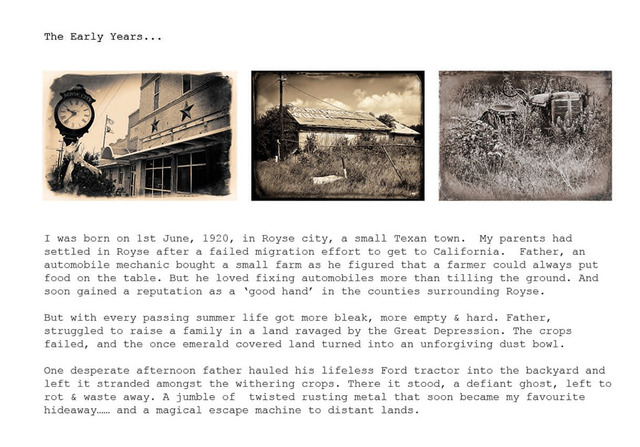

Curators’ note: Prabir assumed the character of his imagined protagonist “John Miller,” a crop duster from a small town in Texas with a passion for photography. He created a full narrative, even going to rural Texas to photograph where Miller lived before being shipped to Bengal. The barn with the name “Miller” on it shown here comes from that trip. Prabir created six triptychs with writing as well as a “diary” documenting Miller’s experiences . . . ending in his (imagined) fiery death on a mission in Japan.

They say most journeys begin with a single step. Yet some travels, like fleeting dreams, have no beginning . . . and no end.

I had just turned four when my father, an army officer, was posted to Srinagar. Most afternoons my sisters and I would watch my mother, an Indian classical dancer, gracefully practicing her “bharat-natayam” dance moves. Those hypnotic images, of light-infused languid motion, were magical!

It was my first step.

My maternal forefathers were farmers . . . and, passionate storytellers. I must have inherited some aspect of their ancient nature as I struggle to create pictures that evoke contemplative imagination. It’s instinctive. Why? I suppose that no matter who and what we are, we all love hearing stories.

When I first saw the photographs that Jerri and Alan had bought at a sale in Chicago, my mind went blank. Momentarily. As if an unseen hand had cleaned my mental canvas, knowing that it would be filled and overflowing in the days to come . . .

It was as much a journey of self-discovery as it was an exhausting effort, retracing the invisible steps of an American “man-of-war” now long gone.

They say the dead never come back. Wrong.

Fig. 23. Purkayastha, Prabir, John Miller—The Early Years, triptych #1 from a series of 6, 2015, three 9x12” images on 18x44” paper, archival inkjet prints on Hahnemulhe Bamboo paper, courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 23. Purkayastha, Prabir, John Miller—The Early Years, triptych #1 from a series of 6, 2015, three 9x12” images on 18x44” paper, archival inkjet prints on Hahnemulhe Bamboo paper, courtesy of the artist.As both curators and participating artists, we walked a fine line. We purchased this collection more than twenty-five years ago but did not focus our attention on it until many years later. We appreciated the images for their aesthetic construction, for enabling us to enter a different world, for their sensitivity . . . but we had no idea what they actually meant. We needed both Indian artists and anthropologists to provide the insight we lacked. And we had no idea what the reaction of Indian artists might be.

Fortunately, they responded positively and saw things in these images that we did not. We were extremely careful not to influence the artists — we gave each participant both physical and digital copies of all 127 images in the collection. If they were interested, we only asked them either to incorporate some of the images in their entirety, deconstruct them, or simply allow the images to percolate and inspire their creativity in any way they saw fit. Each responded enthusiastically and in a different way, independent of both one another and whatever opinion we as curators might have had. The resulting exhibit is a vibrant exploration of the many ways we find/create meaning in images, especially when there is limited factual information available.

As the world becomes more interconnected, understanding the cultural contexts we each bring to interpreting photographs becomes more and more significant. The public programs that accompany the film and exhibit address those issues. For example, although we as individuals may be well educated, we were unfamiliar with the nature and extent of the Bengal famine of 1943. Every Bengali knows this story, and most of our artists referred to it in some way in their work. They saw evidence or lack of evidence in the images to which we were absolutely blind. To our knowledge, Following the Box is one of the first attempts at a cross-cultural visual reinterpretation of historic images. It is visual storytelling across space, time, and culture, a tale of old photographs and new artistic interpretations.

For more information and a slide show of all the images by the still-unidentified photographer as well as the work of all participating artists, please visit our website, http://followingthebox.com.

ALAKANANDA NAG (b. 1977) studied documentary photography and photojournalism at the International Center of Photography, New York. Her interests lie mainly in lesser-known stories, among them two long-term projects, “Armenians of Calcutta” and “Nowhere People — Lives of People in the Indo-Bangladesh Enclaves.” Alaka is the India correspondent for the American photo magazine Foto Visura, for which she has interviewed, among others, Raghu Rai, Graciela Iturbide, and Shahidul Alam. Alaka has also worked with developmental agencies such as UNICEF, Oxfam, and Action Aid.

AMRITAH SEN (b. 1973) studied art at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan, where she received an MFA in 1999. Her main focus has been the book art form. She has been part of group shows across India, Europe, and the United States; has had nine solo exhibitions in Kolkata, Delhi, and Mumbai; and participated in the Dhaka Art Summit and the India and United Art Fairs. She has done residencies in various South Asian countries with her own projects and participated in research programs organized by Khoj Kolkata, Art Ichol, and NexUs Kathmandu. She is also the co-curator of Things Lost / Remembering the Future, a series of pan–South Asian art shows, and is currently a finalist for the 2018 Sovereign Asian Art Prize.

CHHATRAPATI DUTTA (b. 1964) graduated in 1987 from the Government College of Art and Craft, in Kolkata, where he was recently named principal, and earned an MFA from Kala Bhavan, Shantiniketan. He has exhibited in major group shows in India and abroad since 1987 and works in video, theater, television film, and installation art. Chhatrapati has taught in the Department of Painting at Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, and is a founding member of Khoj Kolkata, an international alternative arts group.

MAMATA BASAK (b. 1956) earned her degrees in both painting and sculpture from the Government College of Art and Craft (Kolkata). She was featured in four-person shows in 1981 and 1983 at the Academy of Fine Arts and has exhibited in several group shows in Delhi and Mumbai. Mamata’s work was selected for the annual shows of the Birla Academy of Art and Culture from 2003 to 2010, and in 2010 was honored with a solo exhibition.

PRABIR C. PURKAYASTHA (b. 1952) worked in India’s leading advertising agencies. He received the Habitat Award for Best Photography Exhibition in 2002. For his decade-long project in Ladakh, he received the Gold Master Printers Award, the international B/W photography Magazine Spotlight Award, and the silver SAAPI award. Ladakh was voted Book of the Month by Better Photography (UK) in 2006. Prabir has had solo exhibitions in New York, Chicago, London, Katonah, Los Angeles, Cologne, New Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai and was a featured artist at New York’s Rubin Museum of Art and at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery. In 2009, Prabir was nominated for the international Prix Pictet Award and was named one of the Super Six Photographers of 2009 by Fuji Film, India.

SANJEET CHOWDHURY (b. 1966), an independent photographer, filmmaker, and curator, is a graduate of St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. His photographs have been showcased in exhibitions in London, New York, and Basel, and extensively published in books and magazines. His films have had screenings internationally: at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; in Transmediale, a media and art festival in Berlin; in Tel Aviv, Stockholm, and Shanghai; and at various film festivals across India. Currently he is working on two book projects: Little Europe (his documentary of old European colonial towns along the Hoogly River) and an anthology of the culinary history of Bengal. Sanjeet is a collector of albumen and silver gelatin prints, glass negatives, and daguerreotype plates. He owns a film-production house and is one of the leading collectors of nineteenth- and twentieth-century lithographs and oleographs from India.

ALAN TELLER (b. 1946) received his BA in anthropology from Queens College CUNY and postgraduate training in anthropology and photography at Indiana University. He founded the Inner-City Photo Workshop, a Chicago center for high school dropouts, and was photographic researcher for the Field Museum of Natural History, where he also taught classes in photography and anthropology. Alan founded Teller Madsen, a museum exhibit design company that has developed more than one hundred exhibits nationwide. He has taught at Columbia College, the School of the Art Institute, Purdue University, and Lake Forest College in both art and history departments.

JERRI ZBIRAL (b. 1948) received her MFA in photography from the Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, New York. She founded and directed community photography programs for the Public Art Workshop and the Community Arts Center of the Uptown Hull House in Chicago. There, she worked as arts administrator, teacher, and director of a special photography program for the hearing impaired. With Alan Teller, she is a partner in The Collected Image, exhibiting vintage and contemporary photography and appraising photographic collections. She directed and produced the award-winning and internationally screened documentary films Never Turning Back: The World of Peggy Lipschutz and, with Alan Teller, In the Shadow of Memory: The Legacy of Lidice.

We would like to thank Marta Nicholas and Ralph Nicholas, former Dean of the College at the University of Chicago, Chair of the anthropology department, current Chair of the Board of Trustees of the American Institute of Indian Studies, and a renowned scholar of Bengali culture, who have mentored this project from its inception. We are grateful for their insight and friendship.