The Odyssey of an Amateur Chinese Photographer: Nostalgia, War, and Exile in the Work of Jin Shisheng

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Jin Shisheng (金石声; legal name, Jin Jingchang) has the dual identities of an outstanding urban planner and a pioneering amateur photographer. Born to a merchant family in Wuhan in 1910, Jin Shisheng taught himself photography at the age of thirteen, when he received his first Kodak camera. He started his photographic career in 1930s Shanghai, when he studied civil engineering at Tongji University. Embracing the definition of an amateur as a serious and creative artist, Jin contributed greatly to popularizing art photography and promoting modernist experimentation. In particular, the launch of an innovative photographic magazine called Flying Eagle (Feiying飞鹰) in 1936, with him as editor in chief, established an inclusive style of embracing sophisticated pictorialist photography as well as modernist exploration, representing a broad spectrum of modern Chinese photography.[1]

In 1938, with the support of Professor Erich Reuleaux at Germany’s Technischen Hochschule Darmstadt (Darmstadt University of Technology), who was a visiting professor at Tongji University from 1934 to 1937, and a scholarship from the Humboldt Foundation, Jin Shisheng went to Germany to study road and urban engineering. He and his colleague Li Guohao took the Italian liner Conte Rosso from Hong Kong to Venice and from there traveled to Switzerland, where they boarded the train to Darmstadt. A self-portrait taken in Venice marks the final departure point of his odyssey to become a foreign student in Germany (figure 1).

The year 1938 was a turbulent one in Europe; Nazi Germany was on the rise and an atmosphere of tension was pervasive throughout the world. Jin Shisheng escaped from the Sino-Japanese War, which had erupted in 1937, but was unfortunately caught up in another war: the European front of World War II. The result was that he stayed in Darmstadt until after the war ended — longer than he had originally planned. The seven-year odyssey of this Chinese photographer represents an unusual transnational encounter between China and Germany.

Fig. 1. Jin Shisheng, On the Way to Germany (Jin Shisheng and Li Guohao in Venice), 1938, self-portrait, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 1. Jin Shisheng, On the Way to Germany (Jin Shisheng and Li Guohao in Venice), 1938, self-portrait, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.1. Photography and Nostalgia

A 1939 photograph shows Jin Shisheng as an engineering student, drawing in his study in Darmstadt (figure 2). A calm and tranquil atmosphere permeates the room. Jin, as the subject in this image, appears to be fully engaged in his work. On the wall, three photographs taken in 1930s China contrast with the European-style domestic environment. If we zoom in on one of the photographs, we see an early pictorialist work of Jin’s from 1934 featuring the beauty of Slender West Lake in of Yangzhou, his hometown (figure 3). In this work, he intentionally uses the traditional Chinese “moon gate” as a device, framing the landscape of the arched bridge and weeping willows by the lakeside to create the visual effect of a Chinese circular fan. In the foreground, he captures a scene of everyday life: A little boy sitting on the gate shows his back to the audience; a young woman stands beside him, talking and smiling at him. Accompanying the photograph is a short poem he wrote: “A picturesque landscape with the lake and the reflections of clouds; the visitors are characters in this beautiful painting.”[2]

Fig. 2. Jin Shisheng, Drawing in his study in Darmstadt, 1939, self-portrait, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 2. Jin Shisheng, Drawing in his study in Darmstadt, 1939, self-portrait, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 3. Jin Shisheng, Slender West Lake, 1932, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the Estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 3. Jin Shisheng, Slender West Lake, 1932, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the Estate of Jin Shisheng.Although he defined the landscape in a picture, his creation goes beyond the works of contemporary Chinese pictorialist photographers. Instead of borrowing the subject matter from literati paintings, his was a pioneering technique for depicting the daily life of his subjects. The juxtaposition of a prosaic scene and the eternal beauty of the landscape marks a remarkable break with the emulative representation of landscape. In the 1930s, several photographers based in Shanghai and Hangzhou had an aesthetic sensibility similar to that of Jin Shisheng. Lu Shifu (卢施福) and Wu Yinxian (吴印咸) in Shanghai and Luo Bonian (骆伯年) and Guo Xiqi (郭锡麒) in Hangzhou deliberately combined the traditional pictorialist landscape with depiction of everyday life. Their efforts contributed to the diversity of subjects and styles now evident in modern Chinese photography.

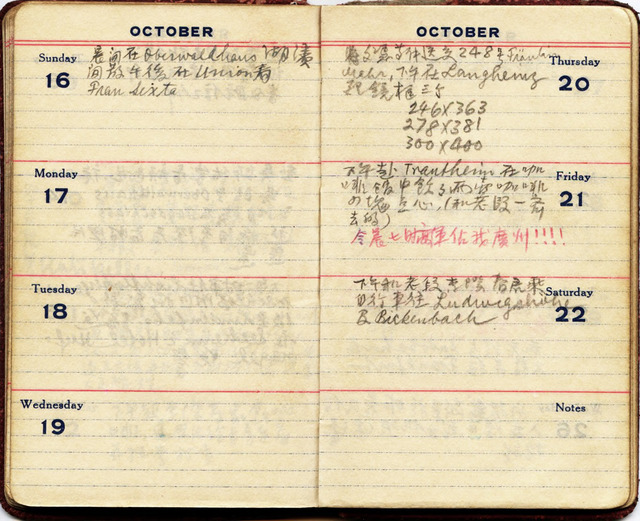

Fig. 4. Jin Shisheng, Diary October 21, 1938, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 4. Jin Shisheng, Diary October 21, 1938, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.In Darmstadt, however, Jin Shisheng developed a spiritual connection between his temporary environment in Germany and his distant hometown through the juxtaposition of self and the pictorialist landscape. Trapped in war-torn Europe, photography became his spiritual sanctuary and a relief from the daily horror. In the first two years of his stay, the increase in European tensions haunted him. On his first day in Darmstadt, he expressed his anxiety in his diary: “When returning home late, the downtown was silent and nobody was there; probably the war is approaching.” The following month, the news of the Japanese invasion of China greatly agitated him. On October 21, he wrote in red pen: “The enemy occupied my Guangzhou at seven o’clock this morning!!!!” Five days later he wrote, “The enemy occupied my Hankou at about eight o'clock this morning!!!!” (figure 4). The four red exclamation points suggest his agitation. The deteriorating situation stimulated his nostalgic desire for home and a peaceful life. Pictorialist landscapes in his hometown gave him spiritual comfort.

Fig. 5. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait in his dormitory at Tongji University, Shanghai, 1936, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 5. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait in his dormitory at Tongji University, Shanghai, 1936, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.Both the 1939 photograph in Darmstadt and a 1936 self-portrait in Jin Shisheng’s dormitory in Shanghai offer intimate insight into his spiritual world and artistic aspirations. The 1936 self-portrait in Shanghai very clearly reveals his artistic vision in the 1930s (figure 5). According to Wu Hung’s perceptive analysis of the various objects and images in this compact space, the two magazines —The Young Companion (Liangyou, 良友), a pictorial featuring splendid modern and urban culture in Shanghai, and the German Photofreund Jahrbuch (German Photography Yearbook) — symbolized his two main inspirations for photography: The former is the flourishing Shanghai urban culture that contributed to “a cultural climax of Chinese modernity,” as Leo Ou-Fan Lee put it; the latter is the foreign impact of modernist photography movements in Europe and the United States.

In Jin’s 1936 self-portrait, there are international photography magazines on the shelves beside him: four issues of Das Deutsche Lichtbild (German Photography Annual), the Japanese photography album International Photography, the International Portrait Photography Catalog, and the British Journal Photographic Almanac. This collection indicates that he was open to pioneering photographic ideas and techniques from all over the world.[3]

Fig. 6. Jin Shisheng, Broadway Mansions under Construction, Shanghai, 1934, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 6. Jin Shisheng, Broadway Mansions under Construction, Shanghai, 1934, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.In 1930s Shanghai, urbanites such as Jin Shisheng embraced a new era of photographic awareness. An increasing number of amateurs and hobbyists from the emerging bourgeoisie and new intellectuals treated photography as an expressive medium and a leisure activity. The intellectuals and artists in mainstream art circles in Beijing and Shanghai promoted the legitimation and popularization of art photography, creating the institutional structures to expand greater public understanding of modern art and the impact of the modern artist. Jin seems to straddle the styles of both pictorialism and modernism with his sophisticated skills. The magazine Flying Eagle welcomed pictorialist photography as well as modernist works.

Jin’s attempt at modernist photographic language began with capturing urban architecture in Shanghai’s Bund. The 1934 photograph of Broadway Mansions under construction demonstrates his modernist exploration (figure 6). Adopting a dramatic diagonal, he took a “worm’s-eye” view of the building under construction. Steel beams and architectural components were the materials of his trade and something he was drawn to in his images of cities. Looking through a series of arcs and beams, he framed the building under construction within the steel girders of the Garden Bridge, showing his skillful application of modernist photographic expression.[4]

Deploying a new perspective on architecture, Jin Shisheng responded creatively to the exciting movements in modernist photography in Europe between the wars. Artists cultivated a “new objectivity” that offered perspectives for seeing the world anew and reshaped the perception of photography. Their disorienting dramatic viewpoints communicated the dynamism of the modern world and characterized a modernist imagery for a technologically developed Europe during that time.[5]

Given Jin’s enthusiasm for capturing architecture and exploring new perspectives, it must have been a huge disappointment when he arrived in Germany in 1938. In the Nazi era, the modernist experimentation in photography was abruptly halted. A flood of superficial images inspired by the propaganda of totalitarianism appeared in magazines and public spaces. Das Deutsche Lichtbild (German Photography Annual), his favorite magazine before he came to Germany, had been suspended in 1938. In 1939, with the help of his friends, he received a French photography annual, Photographie (Photography) from Shanghai.[6] Compared to the prosperous photographic environment in Shanghai before the Sino-Japanese War, the strict censorship of art and photography in Nazi Germany blocked the chance to draw on the inspiration of modernism. One exception in Jin’s work is a photograph of the Hochzeitsturm (Wedding Tower), an example of landmark architecture of the Jungenstil (Art Nouveau) movement in the artists colony of Darmstadt (figure 7). He used a diagonal angle from ground to sky that is classically modernist to depict the renowned “five fingers” profile and the detailed relief of the tower. In contrast to the dynamic shot of Broadway Mansions in 1934, the representation of the Wedding Tower appears to be a silent symbol of the modernist art that was absent in the Nazi era.

Fig. 7. Jin Shisheng, Wedding Tower, taken in the artists’ colony of Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 7. Jin Shisheng, Wedding Tower, taken in the artists’ colony of Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.Lacking modernist inspiration, Jin Shisheng switched from the modernist vocabulary evident in his Shanghai-era work to appropriating the elements of pictorial photography, which enabled him to work with traditional Chinese motifs while away from home. During a trip with friends in 1942, he took several photographs featuring a retreat to pictorial conventions and a tendency toward literati aesthetics. For example, characterized by hazy pictorial effects, he shows two German women sitting on a rock, the subjects in the foreground, heads bowed and whispering to each other. In the background, the mountains fade into mist. Willows, as a decorative frame, appear in the upper part of the image (figure 8).

Another pictorialist image of the same two women illustrates Jin’s highly developed photographic techniques in terms of the depiction of subjects (figure 9). He employed a look-up perspective, highlighting the women’s cheerful emotions. In addition, he used a convention that added an inscription and a seal in the center of the photograph to indicate its location and date, which was an appropriation from traditional Chinese paintings.

Fig. 8. Jin Shisheng, Travelers on the mountain in autumn, Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 8. Jin Shisheng, Travelers on the mountain in autumn, Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 9. Jin Shisheng, Whisper, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 9. Jin Shisheng, Whisper, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.It is interesting that these two photographs, both alluding to literati tradition, were collected in one of Jin Shisheng’s private albums. According to Christian Peterson, Jin began to assemble albums just before his departure for Darmstadt.[7] The treasured ones he took along to Germany and then brought back to China contained approximately seventy representative pictorialist photographs taken in 1930s Shanghai; the only exceptions are these two 1942 photographs in the countryside around Darmstadt. However, these two photographs are unexpectedly consistent with the other pictorialist works depicting everyday subjects and rural landscape in his hometown and Shanghai. The photographs in the two albums are almost poetic meditations on nature, highly evocative of dreamy nostalgia for a peaceful life.

Essentially an escapist mode of photography that saw the world through an idealized lens, pictorialism drew associations with nostalgia for the landscape plundered by the Industrial Revolution and the wars of aggression. Jin Shisheng, a self-conscious photographer, strove to look to the past not only for his artistic aspiration, but also as a way of alleviating the anxieties of displacement and creating a sense of belonging in a foreign land.

2. Private Memory of the War

The most exciting thing for Jin Shisheng in 1939 was his purchase of a Leica camera and a set of lenses for a very low price. Europe was in economic turmoil during World War II, and photographic equipment was available for bargain prices. Jin spent most of his money on for this because he felt uncertain about the future.[8] After he earned his engineering degree, in spring 1940, the increasingly intense war made Jin’s plan to return home impossible.[9] In 1941, Jin became a teaching assistant for his supervisor Friedrich Reinhold at the Institute of Road and Urban Engineering of Darmstadt University of Technology. In autumn 1943, Jin Shisheng moved to the small village of Rohrbach, just outside Darmstadt, to avoid airstrikes. In his diary, he recorded three bombings: Two — one on 23 September 1943 and the other on 26 August 1944 — damaged the house he was living in, but neither was life threatening. A third airstrike, on 11 September 1944, Jin called a “carpet bombing” because it caused huge destruction throughout Darmstadt and created a firestorm.[10] Four weeks later, Jin entered the city and took a series of photographs of the devastation.

Andrés Mario Zervigón argued that Trümmerfotograf (rubble photography), documenting the indescribable devastation in German cities, became the dominant genre of photography in mid-twentieth-century Germany. These images were taken in the aftermath of bombings but were not published until later in the decade.[11] In fact Jin Shisheng’s rubble photographs were first published almost thirty-five years later. In 1980, Bert Hensel, from the German newspaper Darmstädter-Echo, interviewed Jin when he accepted an invitation from the Humboldt Foundation to visit Germany. Accompanied by the resulting essay, titled “Nach 35 Jahren: Foto vom zerstören Darmstadt aus China” (“After 35 Years: Photograph of Destroyed Darmstadt from China”), were Jin’s rubble images from 1944. It is interesting to see how his private photographs and individual memories constitute an alternative version of history and contribute to collective memory.

The lead photograph is the view from the museum over today’s Friedensplatz (Peace Square) to burned-out Weißer Turm (White Tower; figure 10). The destroyed landmark was reconstructed and transformed into a monument to the firebombing in September 1944. The two people in the foreground, whom Jin Shisheng deliberately framed, appear to be an embodiment of the photographer himself, both victims of and witnesses to history.

Fig. 10. News photograph from The Darmstädter Echo, 5 July, 1980, showing the view from the museum over today’s Friedensplatz (Peace Square) to the burned-out Weißer Turm, photo by Jin Shisheng, July 5, 1944. © Darmstädter Echo.

Fig. 10. News photograph from The Darmstädter Echo, 5 July, 1980, showing the view from the museum over today’s Friedensplatz (Peace Square) to the burned-out Weißer Turm, photo by Jin Shisheng, July 5, 1944. © Darmstädter Echo.Photographs of the destroyed cityscapes were vital to constructing this complex texture of memory. The rubble images representing German wartime suffering shaped a collective traumatic memory that includes victimhood.[12] Both professional and amateur photographers played a significant role in narrating history and constituting a collective memory of war. As an amateur photographer, Jin Shisheng’s private images and surviving diaries provide an unexpected resource for recalling the past.

The 1980 interview with Jin Shisheng provides more details about the photographic context in the aftermath of the bombing. Bert Hensel writes that Jin took a series of rubble photographs:

Four weeks later, he walked on the street and searched for the subjects of photography in the destructive urban ruins. The Chinese climbed on the Ludwigsmonument and took a view of the bombed-up houses on the Rheinroad from a high vantage point. With a steady hand and extreme concentration, he took a series of photographs, slowly turning around the axis. He glued the pictures together in a panorama, then he bequeathed it to someone from the town, but I do not remember whom. [13]

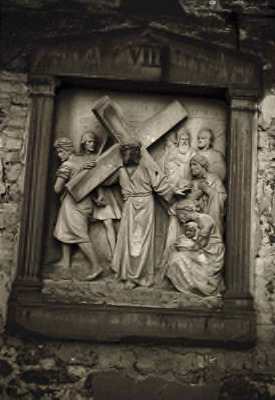

Fig. 12. Jin Shisheng, Sculpture of the Passion of Christ, 1944, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 12. Jin Shisheng, Sculpture of the Passion of Christ, 1944, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.The devastated cityscape of Darmstadt motivated Jin to see the city through his camera. Ruins and death were essentially new topics for him. One of his images is of a bombed-out church with a cross silhouetted against the sky, revealing the potential aesthetic appeal of the aftermath of the devastation (figure 11). However, Jin Shisheng, coming as he did from Allied China, did not celebrate the beauty of destruction, as did the pioneering nineteenth-century war photographer Felice Beato; instead, Jin emphasized the Christian icon — in this case, the cross.[14] Another picture with a Christian metaphor is of a sculpture of the Passion of the Christ on the wall of a church (figure 12). Taken from a slanted angle, the photograph depicts a damaged statue of Jesus with a falling cross in the center as a metaphor for people suffering from the war; the burned stones around the statue are evocative of the catastrophic world.

Jin Shisheng’s capture of a religious icon not only suggests his deep sympathy, but also expresses optimism about rebirth and reconstruction. As an engineer, he participated wholeheartedly in the plan of reconstruction. He attempted to craft an overall impression of the deconstruction of cityscape, making a move to the era of redevelopment and rebirth.

Fig. 13. Jin Shisheng, Ruins in the aftermath of bombing, Darmstadt, 1944, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 13. Jin Shisheng, Ruins in the aftermath of bombing, Darmstadt, 1944, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.He showed his humanist commitment to his subjects, be they bombed buildings, damaged urban infrastructures, or survivors of airstrikes, all of which were subjects for his camera, thus demonstrating a humanist vision. In a rubble photograph taken after the bombing in 1944, he displays a humanitarian perspective on urban destruction (figure 13). Taken from a tower, it foregrounds two boys looking at the buildings, which stretch to the horizon. The distant mountains are a picturesque frame that signifies the end of visibility. He juxtaposes war crimes and innocent children, disorder and harmony, transmitting sympathy for people suffering trauma from the war through the eyes of the children.

Fig. 14. Jin Shisheng, Ruins in the aftermath of an airstrike during Shanghai war, 1932, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 14. Jin Shisheng, Ruins in the aftermath of an airstrike during Shanghai war, 1932, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.Beyond the national narrative and historical justice, Jin Shisheng showed his compassion in recalling the devastating war in his homeland. The rubble photographs he took in Darmstadt evoke the traumatic memory of Japanese bombings in Shanghai twelve years earlier. As a fledging self-taught photographer, he had taken several shots of the rubble brought about by an airstrike during the Shanghai war of 1932 (figure 14). Employing the techniques of pictorialism, Jin depicted the vastness of destruction within a traditionally structured frame. Melancholy and poetic, the dramatic view of clouds of smoke that partly obscured the buildings emphasizes the devastating power of bombing. The apocalyptic vision presages the breakout of full-scale war between China and Japan five years later.

Jin Shisheng’s experiences of displacement, war, and death enabled him to empathize with other people who were also suffering from disaster. In an interview in the 1980s, Jin recounted how he fled the firebombing on 11 September 1944. He recalled the horrible details and described the firebombing as a “bizarres Bild” (bizarre picture). “It was a bizarre picture. The trees shone in daylight, as if someone had turned on a gigantic light bulb. I liked that, but I was too scared.”[15] It is interesting to note that even his oral description of the bombings was still expressed from a photographic perspective: the fiery tree under the strong light appears to be a large bulb, and the world is seemingly to be lit before his eyes. He was overwhelmed by the horrible spectacle, but still liked the “picture” that he took in his brain.

3. Exile and Identity

Jin Shisheng was one of the few Chinese photographers or intellectuals who confronted the life of diaspora and exile. His wartime memories not only provide an alternative version of the war that helps us navigate the present, but also play a critical role in understanding his identity in exile. The abundance of his private snapshots of everyday life and portraits of local people comprised his own evolving cultural identity, one that was never complete, always in process.[16]

When Jin Shisheng moved to the countryside, the institute where he worked moved to this village as well, and for the same reason. It was convenient for him to use its darkroom. Photography for him at that time was not simply a pastime; it was a means of bonding with people and defining his self-identity in a foreign land. Over almost three years, the hardship forged a strong bond between Jin and the local population. According to his memoir, written in 1947, he recalled his precious friendships in Germany: “In wartime, I lived in the countryside and became friends with some fellow villagers. For seven years they treated us very amiably, this is something I never would have imagined.”[17]

One 1939 self-portrait of Jin and his elderly landlady captures a charming moment: The affable woman is knitting as Jin sits next to her, smiling at her (figure 15). This photograph conveys an unusual intimacy and closeness in a comfortable domestic atmosphere. Many of Jin’s images provide a unique insight into the lives of women in wartime. Because most of her male family members had been recruited by the army, Jin accompanied his landlady as if he were family.

Photography serves as an interactive tool of communicating, and makes visible his association with the local community. He attempted to construct a sense of belonging through a series of portraits and domestic photographs of villagers (figure 16). One, a self-portrait with an opera singer in Darmstadt, indicates Jin was closely associated with local artists (figure 17).

Fig. 15. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with landlady, Darmstadt, 1939, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 15. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with landlady, Darmstadt, 1939, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 16. Jin Shisheng, The family of the landlord in Rohrbach, ca.1943, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 16. Jin Shisheng, The family of the landlord in Rohrbach, ca.1943, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 17. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with German opera singer, Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 17. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with German opera singer, Darmstadt, ca.1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.The self-portrait, one of his favorite genres, embodies Jin’s exploration of identity. The self-portrait brings the photographer and sitter into one frame. Historically, it is linked to experimentation with techniques, performance, and, more important, self-identity. Although he left no written record of his motivations behind a series of self-portraits, it is not difficult to imagine that nothing could be more accessible and controllable than his own body. Jin’s earliest self-portrait clearly shows his fascination with experimental techniques: The college student, all of twenty-two years old, employs multiple exposures to create a composite image that reflects his own face in the lens of his Rodenstock camera (figure 18).[18] Unlike this ambitious early self-portrait, the ones from Darmstadt in the 1940s focus on his performance of self beyond technological experimentation. In a 1940 self-portrait, he arranged himself with his new Leica camera in a confined indoor space. Gazing at a mirror, he tugs the self-timer of the Leica, which was supported by a tripod. The subject of this image, simultaneously the photographer and the camera, stands out against the backdrop of darkness (figure 19). He took a series of self-portraits in this environment from different angles. Using a mirror as a reflexive surface, he created a self-reflexive image or “meta-picture” that refers to “its own production process or the result of that process.”[19]

Fig. 18. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait in Rodenstock lens, Shanghai, 1932, composite photograph, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 18. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait in Rodenstock lens, Shanghai, 1932, composite photograph, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 19. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with Leica, Darmstadt, ca. 1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 19. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait with Leica, Darmstadt, ca. 1940, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 20. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait, ca.1940, composite photograph, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 20. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait, ca.1940, composite photograph, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.The self-reflexive image not only shows the process of self-photographing; it also provides an insight into the complexity and ambivalence of the inner world of the photographer. In this double self-portrait, he ingeniously brings the photographer and the subject into one image with multiple exposures, creating a stage of performance for two selves: the one is roaring and the other is photographing, which might symbolize two different states of Jin himself (figure 20). The performative story conveys the emotions of ambivalence and struggle in his inner world.

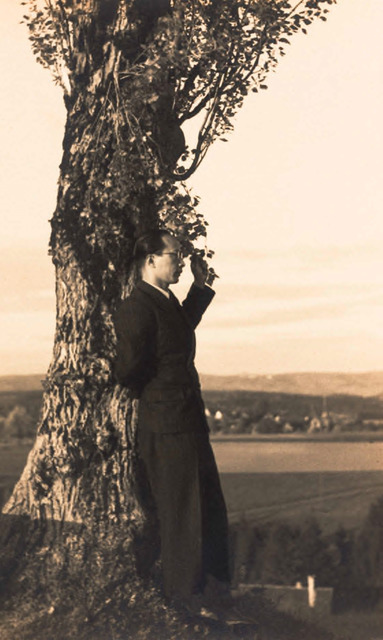

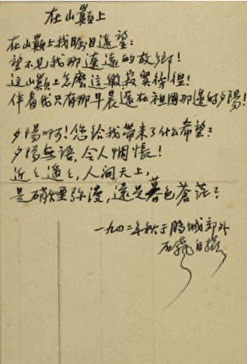

One might find a trace of self-entertainment in some of his indoor self-portraits, but the ones taken outdoors, probably while he was traveling, clearly convey loneliness and the longing for home. In a 1942 self-portrait, he places himself in the center of the photograph and shows his profile to the viewers. He leans on a lofty tree, gazing into the distance against the background of the foreign landscape (figures 21 and 22). The photograph has an air of serenity. Amid the tranquil landscape, he appears to be enjoying the fine view, but the poetry written behind this image expresses a completely different state:

Fig. 21. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait, Darmstadt, 1942, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 21. Jin Shisheng, Self-portrait, Darmstadt, 1942, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng. Fig. 22. Jin Shisheng, Zai Shan Dian Shang (“At the Summit of the Mountain” - poem accompanying self-portrait), 1942, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 22. Jin Shisheng, Zai Shan Dian Shang (“At the Summit of the Mountain” - poem accompanying self-portrait), 1942, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.Exile and the longing for home, the self-portraits, and his texts express the emotions associated with fear, anxiety, and a desire for home. When Jin Shisheng was returning to China, in 1946, he took a self-photograph on the deck of the ferry against the backdrop of Huangpu River in Shanghai (figure 23). In it, he stands comfortably and is smiling. This photograph marks the end of his odyssey. As a manifold voyage over different domains, Jin’s exile during wartime implies not only movement across the borders of nations, but also the experience of traversing the boundaries of art, culture, and languages.

Jin Shisheng as a self-conscious photographer worked with traditional Chinese motifs while away from home, expressing his nostalgia for a life of peace. His individual wartime memories associated with private photographs and diaries provide a different perspective on the history, and develop a new understanding of the impact of exile on the evolution of identity.

Fig. 23. Jin Shisheng, Return (self-portrait on the deck of the returning ferry), 1946, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.

Fig. 23. Jin Shisheng, Return (self-portrait on the deck of the returning ferry), 1946, gelatin silver print, courtesy of the estate of Jin Shisheng.Qiuzi Guo is a PhD candidate in the Institute of East Asian Art History at Heidelberg University. She is completing her dissertation, titled “When Kodak Came to China: Photography, Amateurs, and Modernity, 1900–1945.”

Notes

I am grateful to Jin Hua for showing me the photographs of his father, Jin Shisheng, taken in China and Germany. The research is based on the private collection of Jin Hua. See the chronology of Jin Shisheng in “Jinshisheng nianbiao” (金石声 (金经昌) 年表 [“Chronology of Jin Shisheng”], in Chenji: Jin Shisheng yu xiandai zhongguo shying (陈迹:金石声与现代中国摄影) [Relics: Jin Shisheng and Modern Chinese Photography], edited by Jin Hua (Shanghai: Tongji University Press, 2016), 675–85.

Original text is “湖光云影都如画,游人权作画中人。”Relics: Jin Shisheng and Modern Chinese Photography, 315.

Wu Hung, “Self as Art: Jin Shisheng and His Interior Space,” in Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China (London: Reaktion Books, 2016), 64–87.

Sarah E. Fraser discusses the modernist vocabulary that Jin Shisheng employed in portraying architecture in Shanghai in “The Importance of Home: Shanghai and Darmstadt,” in Relics, 525–39.

Andrés Mario Zervigón, “The Weimar Era and Photo-consciousness, 1919–1932,” in Photography and Germany (London: Reaktion Books, 2017), 83–119.

Jin Hua, “Material Compilation: The Years Jin Shisheng Studied and Photographed in Germany,” in Relics, 654–73.

The first album contains forty early pictorialist photographs taken between 1930 and 1934, when Jin, in his early twenties, studied in Shanghai. The second album consists of twenty-four photographs, taken in the mid- 1930s, showing a transitional style from pictorialism to modernism. Both survived the Cultural Revolution.

Wu Yinbo, a photographer and close friend of Jin’s, recalled a story about a Leica camera. Jin told him that in March 1945, when they occupied Darmstadt, US soldiers picked up an entire set of his equipment: a Leica camera and lenses and all his negatives. Jin went to the military police to ask for his belongings back. The US Army returned his negatives but claimed that no one had not taken the camera and lenses. Jin showed the photographs of his camera and lenses as proof of ownership. Finally, the army promised to replace the lost equipment but told Jin to get the new cameras from the Leica factory himself. Over the next 40 years, the Leica camera and lenses always accompanied him. See Wu Yinbo, “A Good Mentor Remembers Mr. Jin Shisheng,” in Chinese Photography, no. 11, 1999, reprinted in School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, Jin Jingchang [i.e., Jin Shisheng]: A Commemorative Collection of Prose (Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, 2002), 215. See also Jin Hua, “Material Compilation: The Years Jin Shisheng Studied and Photographed in Germany,” in Relics, 654–73.

According to the memoir of his colleague Li Guohao, who went to Germany with him, Jin went to Berlin to see if they could return to China, but the reply was overwhelmingly negative. Li Guohao, zhanhuo fengfei de liude shenghuo, 战火纷飞的留德生活 “The War-Ridden Life of Overseas Studying,” in Recalling Study in Germany, eds. Wan Mingkun, Tang Weicheng, et al. (Beijing: Commercial Press, 2006), 188, cited in Jin Hua, “Material Compilation,” in Relics, 654–73.

Jörg Friedrich, Der Brand Deutschland im Bombenkrieg 1940–1945 (The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, 1940–1945), Propyläen Verlag 3. Auflage edition (1 November 2002), 20.

Andrés Mario Zervigón, “History, the Future and Photography, 1946–1989,” in Photography and Germany, 155–188.

Steven Hoelscher, “‘Dresden, a Camera Accuses’: Rubble Photography and the Politics of Memory in a Divided Germany,” in History of Photography, volume 36, no. 3 (August 2012): 288–305.

Andrés Mario Zervigón, “History, the Future and Photography, 1946–1989,” in Photography and Germany, 155–88.

Bert Hensel, Darmstädter Echo, 5 July 1980. Ten years later, this legendary story of Jin Shisheng was adapted into a short essay entitled “Chinese flieht in Todesangst” (“Chinese Flees in Dread”) in a special issue commemorating “Die Brandnacht” (“Fire Night”) on 10 September 1990 Darmstädter-Echo.

Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” in Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews, Nicholas Mirzoeff, ed. (New York: Routledge, 2000), 21–33.

For more discussion of this self-portrait, see Wu Hung, “Photography about Photography: Jin Shisheng and His Interior Space,” in Relics, 30–47; and Richard K. Kent, “Flying Eagle: Jin Shisheng and the Cause of Photography in 1930s China,” in Relics, 366-383.

Hilde van Gelder and Helen Westgeest, “Self-reflective Photography,” in Photography Theory in Historical Perspective: Case Studies from Contemporary Art (Chichester, West Sussex, and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 190–226.

The poem was translated by Richard K. Kent; cited in Jin Hua, “Material Compilation,” in Relics, 576.