Iconology of a Photograph

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

I. Strangeness

Let me say it up front. The essay is not about applying to photography the methodology implied by Erwin Panofsky’s term “iconology.” The intention is to return to a key moment in his interpretation of visual images. Panofsky’s scholarly reach encompassed the area of medieval and early-modern European art, but his iconology ensues from a seemingly interpersonal encounter with artworks he compares to a chance meeting with an acquaintance who tips his hat in greeting. Instead of responding to the artwork as he might the acquaintance — that is, with a sense of familiarity — Panofsky goes into an elaborate interpretative tailspin.

Iconology is based on a belief that “something else” lies beneath the seductive familiarity of artworks.[1] I want to apply this interpretative turn to photography. Like Panofsky’s acquaintance, a photograph tempts familiarity and easy cultural access perhaps more than the medieval manuscripts or Baroque paintings he studied. Iconology demands that the familiar referent be made progressively uncanny and strange.[2] In a single image, I want to explore this Panofskian complication.

II. Encounter

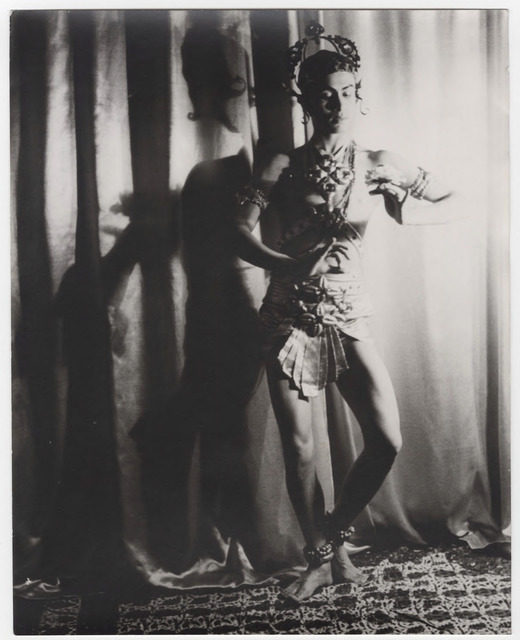

(Figure 1) I recently came upon this image in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, at Yale University. In rich black-and-white tones, it shows a young dancer, wrapped in lavish ornaments, making hand gestures that recall Indian dance. The metadata mentions that the photograph is of an Indian dancer, Ram Gopal, taken by an American photographer, Carl Van Vechten, in his apartment-turned-studio in New York City in the spring of 1938. The image is part of a set of more than one hundred in which the dancer, wearing a variety of costumes, poses in front of the camera while the photographer adjusts the focus and the distance between the camera and the body, framing half- and full-length figures tightly within an upright, rectangular frame. Different lighting arrangements and a range of backgrounds suggest deliberate experimentation. Whereas a printed fabric and even lighting flattens the image, here a play of light and shadow makes the statuesque figure glow against a plain, heavy curtain. The image grabs me in a Panofskian way, as a puzzlement (Panofsky calls it “the riddle of the Sphinx”) that leads to an experiment in iconology.

III. Iconography: Take One

By turning to the metadata at the Beinecke, naming “the Indian dancer” and “the American photographer,” and situating the photograph within the larger corpus of Van Vechten images, I have already said too much. The first interpretative move for Panofsky is what he calls “pre-iconographic," or formal and visual, observations of the image. These observations are hardly sufficient in themselves, but they provide the foundation on which a historical understanding must be built. I also broke Panofsky’s rule for historical investigation by implying intentionality to the play between the body and the backdrop. The task will be to resist easy reading and train the investigation toward a historically specific iconography of the image. In this case, the iconography will depend on how I ask at least two more questions: What is the Indian dancer presenting to the camera? and What is the American photographer seeing from the other side of the lens?

I knew nothing about the dancer or the photographer when I chanced upon the image. I subsequently learned that Ram Gopal (1912–2003) was a major participant in a movement to reform dance in South India in the 1930s. His autobiography, published in 1957, describes a passionate interest in dance since childhood. As a young boy, under the patronage of the Maharaja of Mysore, he studied a narrative form of temple dance called the Kathakali at the Kerala Kalamandalam, which was established by a celebrated poet, Vallathol, in the Malabar. Ram Gopal also learned the Kathak, a form of North Indian dance whose presence in the southern Indian city of Bangalore suggests a cosmopolitan dance culture spreading across India in the 1930s. Ram Gopal toured temple sites in Tamilnadu to study the traditional, temple and courtly, dances that were being reformulated as the Bharata Natyam in the nearby city of Madras. In 1938, he was carrying his mission for the first time to an international audience, promoting dance as a new, pan-Indian practice with its own discipline and spirituality shared by all regional styles he had studied.

While some of Van Vechten’s photographs show Ram Gopal wearing the Kathakali’s tall, haloed crown, in this image we see no specific reference to his training. Instead, the stance and hand poses seem to employ a generic language of gestures (mudras) used in Indian as well as southeast Asian dance. Ram Gopal also disavows the voluminous skirt of a Kathakali dancer. His naked limbs are in reaction to the layers of garments covering the body of the traditional dancers he had studied in Bangalore, which he dismissed as a reflection more of Victorian prudery than of Indian traditions. Instead, his effort was to reproduce the sensuous, divine figures carved on ancient Indian stone temples of Halebid, Belur, and Somnathpur in the Mysore State.[3]

In re-creating dance in the image of ancient religious sculpture and distancing himself from current practice, Ram Gopal aligns his reinvention with the primary leaders of the reform movement in Madras (now Chennai). In Madras, the new dance form was called the Bharata Natyam. Although designed as a performance style for the modern proscenium stage, it was named after the sage Bharata’s sixth-century treatise on the dramatic arts called the Natyasastra. The Bharata Natyam counteracted a nineteenth-century dance, called nautch or sadir, performed traditionally at the local royal courts and temples by women called devadasis, or slaves to the god.

The Bharata Natyam intersected with a number of socio-political movements: feminist activism against the exploitation of young girls who were ”married to the temple” and trained to perform erotic dances; nationalistic struggles against the British colonial rule, in which the authenticity of local cultural traditions gained value and currency around which a sovereign nation could be imagined; and the interests of an educated, urban middle class to retrieve and refine the formal aspects of dance against their recent decadence by linking Bharata Natyam to ancient Sanskrit texts and Hindu temple sculpture. The Bharata Natyam experiment resulted in what Uttara Asha Coorlawala calls “the sanskritization of the dancing body.”[4] It created, in the 1930s, a new, cosmopolitan awareness of dance in cities such as Madras and Bangalore. By assuming elegantly stylized hand positions and a measured pose of relaxation to reflect temple sculpture, Ram Gopal transforms himself into such a Sanskritized figure in front of Van Vechten’s camera.

IV. Iconography: Take Two

Sanskritization aimed to turn the dancer’s body into an asexual figure representing a cultured body-text. Standing in front of the camera, Ram Gopal produces an arrangement of decorative outlines, accented by bold armbands, chest ornaments, and a wired tiara that curls out into tendrils on either side of his ears. What eroticizes the decorative silhouette is the photograph. Raking light sculpts out the musculature of the youthful dancer. On the right, the figure melts into the glow of the background curtain. The satiny fabric reflects the softness of his skin; shadows flicker across the columnar folds like a ghostly double of the body. The camera brings the luminous, pulsating composition into a tight focus.

The photographer chooses the setting. We know this by comparing images of Ram Gopal with Van Vechten’s other images. Many backdrops from the Ram Gopal set reappear a decade or two after the 1938 photo shoot. In 1932, Van Vechten acquired a light, portable Leica camera and converted his midtown apartment into a studio, where he produced a remarkable photographic collection of dancers and musicians who passed through the city.

Described as a tastemaker, Van Vechten began his career as a dance and music critic for the New York Times, Vanity Fair, and other literary and lifestyle magazines, covering a range from Russian ballet to African American club dances in the Harlem district of New York City.[5] By 1938, he was well regarded as a patron of African American musicians and performers of the Jazz Age, and as a promoter of writers and theater personalities who shaped in New York an artistic culture known as the Harlem Renaissance. He promoted black culture among elite white socialites and also brought Harlem to their attention as a commercial site for entertainment and erotic pleasures. His own sexual interests in black men were well known. Photographs of nude men, posing alone or with a white man, bordered on pornography, and he also designed scrapbooks of photographs and newspaper clippings to suggest homoerotic innuendoes in mainstream press. Thus, when we extend Van Vechten’s interracial fascination and investigate what the American photographer might have seen when he trained his Leica on the Indian dancer, the Sanskritized body gains a “homoerotic” meaning.

V. Iconography: Take Three

Is the homoerotic meaning of this photograph, then, an instance of one culture’s body-text lost in another culture’s translation? True, the odds seem stacked against the dancer if the iconography ensues primarily from the photographer’s point of view. Photography, in which the dancer’s body is detached from the living space-time of the performance, could turn that body into a sexual fetish, as Van Vechten’s practice implies.[6] Against this seemingly exploitative logic of photographic translation, however, I suggest that in this image Ram Gopal actively participated in the production of erotic desire.

In his autobiography, Ram Gopal addresses the question of the dancer’s gender and sexuality. Whereas the Madras reformers aimed to restructure the practice for women dancers, Ram Gopal defined his mission specifically as the promotion of “the male forms of temple dancing.”[7] The statement could be seen as reflecting what Hari Krishnan calls, in the context of the Bharata Natyam, the creation of a “hypermasculine, spiritual and patriotic icon of the emergent nation.”[8] The Bharata Natyam became identified with god Shiva, whose icon as the supreme Lord of Dance, Nataraja, seen in the temple of Chidambaram and bronze sculptures of Tamilnadu since the medieval period, became a model to emulate.[9] The idealization helped to disassociate the dance from the erotic practices of the devadasis. Women began performing dances based on male gods such as Shiva and the mythical bird Garuda, although Ram Gopal insisted that such numbers “should be danced by a man” alone.[10]

Ram Gopal’s idea, however, is related less to Bharata Natyam’s ideal of virile divinity and more to his training in the Kathakali. Ram Gopal complicates the understanding of masculinity in Bharata Natyam by mentioning that the Kathakali tradition trains men to play both male and female roles. He writes that his teacher, Guru Kunju Kurup, used to summon him to dance with him after a full day’s strenuous practice of muscles and eye movements, saying: “You shall be the beautiful maiden Damyanti [sic] and I shall be your handsome prince Nala, and I want you to convince [me] by every look, gesture and expression that you are truly, deeply in love with me.”[11] The invitation was not simply to perform the stories from Indian mythology. It was a training in what Ram Gopal calls “bewitching and enchanting himself.” The dancer trained his body to move beyond his own gender and subjectivity in order to become an object of erotic desire for his viewers. It is this technique of transfiguration that Ram Gopal now fully displays in front of Van Vechten’s camera.

In the Yale image, a contrapposto turns his youthful body gently toward the androgyny of figures seen in the ancient Buddhist sculpture of Southeast Asia and Nepal. The pose departs from the discourse of gender within the Bharata Natyam model and turns to the enactment of gender fluidity. In other photographs in the Yale set, Ram Gopal wears the same short lower garment we see in our image but holds a translucent fabric against his body. Thus, through cross-dressing, he accentuates his androgyny toward a veiled, feminine, Salomé-like figure, borrowing from American women dancers such as Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis.[12]

Ram Gopal’s transfigurations could stimulate a homoerotic desire in his male viewer in yet another way, as Kathryn Hansen sees in early-twentieth-century Indian theater. Hansen notes the popularity of male stage actors, such as Bal Gandharva and Jayshankar Sundari, who played women’s roles based on a training similar to Ram Gopal’s Kathakali. The actors were admired for the authenticity of their roles, a claim Ram Gopal also makes in his autobiography. But Hansen documents a “male-to-male dynamic” in those female impersonations, when, for example, a male supporting actor felt a “unique thrill” when standing close to Bal Gandharva on stage, or when young men among the audience gave out a “lusty applause” as the performer appeared surrounded by “her companions.”[13] It is not authenticity, then, but the awareness of the cross-dressed actor underneath the costume that was a source of pleasure for these men.

VI. Iconography: Take Four

So, my next question is: How exactly does Ram Gopal “bewitch and enchant” himself for the American gaze? The program brochure from his New York concert tells us little about the figure his American audience may have seen on stage in 1938. But Van Vechten’s photographs show the dancer freely interpreting his training and molding his body into a proliferation of imaginative representations. In this image, the dancer holds a white lotus in his raised left hand while using mime to pluck the imaginary long stem with his right hand, representing what the concert brochure calls “The Picture of Bodhisattva.”

The body is almost naked except for the metallic ornaments that flatten it and a short lower garment made of large beaded, floral shapes, and stiff, fan-shaped pleats. A shaped-wire tiara, with standing curls on either side, extends outward from the face into a decorative flourish. The costume accentuates the decorative contours of the Sanskritized body, but nothing in it resembles the costumes in Kathakali, Bharata Natyam, or Kathak — the forms that Ram Gopal studied and performed.

In 1938, Ram Gopal’s New York audience would have been surprised by this representation of Indian dance. They associated it with the fame and prestige of Uday Shankar and his so-called Hindu ballet. A reviewer points to the difference between the two dancers: “The gospel of Hindu dancing has been well preached by Uday Shan-kar [sic] and his cohorts, so that the gathering knew more or less what to expect in the nature of the choreographies. But the manner of Mr. Gopal’s dancing, his remarkably fine muscular control, and his fascinating and exotic costumes must have won new converts to the cause.”[14]

As Joan Erdman points out, Uday Shankar choreographed group dances and insisted on the authenticity of costumes for his men and women based on Indian miniature paintings and ethnographic photographs of nautch girls in Rajasthan.[15] By contrast, Ram Gopal danced solo and impressed his audience with a spectacular display of endlessly malleable bodily forms, shaped by an inventive series of unspecifiable costumes.

How to read these costumes? Departing deliberately from Uday Shankar’s naturalistic representations, Ram Gopal’s costumes may, in part, relate to Bharata Natyam. Designed by Rukmini Devi to replace the clutter of the voluminous skirts and scarves of the temple dancers, the Bharata Natyam costume wraps closely around a dancer’s body and lends the dazzle of abstract, linear patterns to her limbs akin to Indian sculpture, emphasized by silk embroidery, sparkling ornaments, and sharply outlined eyes and eyebrows, animated by miming techniques called abhinaya.[16] Ram Gopal embraces Bharata Natyam’s aesthetic framing of the body. Rukmini Devi, however, designed her costumes to transform a female dancer into a visual abstraction, while her male dancers continued in the ceremonial costume of a priest or a dance teacher, wearing a silk dhoti and perhaps a Brahmanical thread or a sash over a naked upper body. Ram Gopal avoids this gendered paradigm of design, but uses the Bharata Natyam’s aesthetic impulse to transform himself into a chimera-like figure capable of taking on fantastical appearances beyond the concerns for consistency and authenticity of the dance forms he had studied.

It is likely that Ram Gopal did not design his costumes. A few months before his New York visit, he had met in Bangalore an American dancer named La Meri, who was known for borrowing from various traditions of world dance as well as their Orientalist re-creations in Hollywood films. La Meri invited Ram Gopal to join her on a tour of Southeast Asia and Japan, his first outside India. Ram Gopal parted company with La Meri in Tokyo and traveled with two suitcases full of costumes to Los Angeles and New York, and then to Warsaw and Paris, dancing solo using tracks of prerecorded music. It is likely that the suitcases contained costumes that were designed for the dancer when he was part of the American troupe. The Yale image shows Ram Gopal experimenting with the Orientalist fantasies of Asia he may have picked up in La Meri’s company.

The short pleated skirt and medallion-studded ornaments Ram Gopal wears relate stylistically to ancient Egyptian sculpture as it entered Euro-American advertisement, dance, and film through the fad of Egyptomania in the early twentieth century. Ruth St. Denis (1879–1968), a dancer who inspired La Meri, can be seen at the turn of the century portraying an Egyptian queen for an American cigarette advertisement.[17] In the 1920s, St. Denis traveled to India and other Asian countries with her partner and husband, Ted Shawn (1891–1972), and together they formed the Denishawn dance company, reputed for choreography based on Asian religious traditions.[18] Ram Gopal’s costume relates more to this global network of American dance and visual culture than it does to India.

In the Yale image, Ram Gopal embodies the American fascination with the East, broadly speaking, in one more detail. He delicately holds a lotus flower in his raised left hand, while suggesting in the right hand the extension of an imaginary stalk of the lily that might have stemmed from his feet. In Kathakali as well as Bharata Natyam, this gesture of holding a flower usually would have been represented through mimetic techniques of the mudras (hand gestures). The use of a paper flower instead may suggest the limits of a still photograph, in which the mimetic representation of unfolding petals could become an illegible gesture. The flower, however, also points to the elaborate pictorial tableaux Ruth St. Denis created from her study of East Asian sculpture, as when she posed as the White Jade Guanyin based on Chinese porcelain for a series of photographs by Ira L. Hill in 1916. Layers of translucent white fabric closely match the folds shown in the original Chinese sculpture, and a lotus stalk is placed in front of the seated Guanyin. Similarly, Ram Gopal holds himself still in front of the camera, as if he was part of a sculptural tableau depicting the androgynous Bodhisattva of Compassion, Avalokiteshvara, holding a lotus.

VII. Iconography: Take Five

Thematically, “The Picture of Bodhisattva” goes beyond Ram Gopal’s training in Kathakali and Kathak. The program note of his performance, for example, makes an unusual link between the Buddhist figure and a passage quoted from the Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita. The connection, difficult to locate in sources relating to the two religions, points to an essay by Ananda Coomaraswamy titled “Cosmopolitan View of Nietzsche,” published in his collection, The Dance of Siva, in 1918. In that essay, Coomaraswamy compares the Bodhisattva to Nietzsche’s Übermensch (Superman), explaining that both figures are self-realized heroes as described in the Bhagavad Gita, “superior to pity, resolute for the fray, but unattached to the result,” and achieve inner freedom by going beyond sensory desires.[19]

Ram Gopal reflects the Nietzschean connection many times in his 1957 autobiography. Talking about his early training in the Kathakali, he writes that Guru Kunju Kurup regularly insisted: “You must become, you must concentrate and feel so intensely all I tell you . . . that you are not conscious of the self. The self is forgotten, unimportant, small, of this world. But that ‘other self,’ the God you are portraying, must come to life by sheer will-power and concentration, and this is possible only if you are completely lost in the rhythm of the moment.”[20] Ram Gopal brings this self-possessed and transfigured “other” body in front of Van Vechten’s camera.

What Nietzsche called an ecstatic mode of self-possession relates Ram Gopal to a larger cohort of modern dancers in Europe and America, among them Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Rudolf Laban, and Mary Wigman.[21] In his earlier writing as a dance and music critic in New York, Van Vechten championed many of these artists, along with African American dancers and musicians. Looking through the lens of his Leica, thus, he would have seen Ram Gopal as a trans-cultural, Nietzschean figure leaving its trace on the photographic emulsion.

VII. “Something else”

Panofsky writes that iconology “deals with the work of art as a symptom of something else which expresses itself in a countless variety of other symptoms, and we interpret its compositional and iconographical features as more particularized evidence of this ‘something else.’”[22] In offering a symptomatic reading of a single photograph in the Yale archives, the essay reveals in it an embedded dimension of global history that brought together widely separated cultures and regions into a sphere of mutual fascination in the early twentieth century. The Yale photograph is a “particularized evidence” of a brief moment when the Indian dancer’s self-presentation and the interracial, homoerotic gaze of the American photographer meet and activate transcultural fantasies of each other. The trace of mutual fantasy-making lends this record the same sense of wonderment Panofsky brought to the acquaintance who greeted him on the street. Instead of returning the greeting intuitively, Panofsky’s inquiry turned in the direction of self-questioning that led him away from his familiar, interpretative surroundings.

The Yale photograph takes me in a direction that is equally counterintuitive in scholarship on images of Asian subjects by Western photographers. Panofsky does not address the subject of photography, but the play between familiarity and strangeness he called historical inquiry is especially useful when dealing with the history of world photography.

Ajay Sinha is Professor of Art History at Mt. Holyoke College. He has authored Imagining Architects: Creativity in Indian Temple Architecture (2000), and edited, with Raminder Kaur, Bollyworld: Popular Indian Cinema through a Transnational Lens (2005).

Notes

Erwin Panofsky, “Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art” (1939), in Meaning in the Visual Arts. Garden City: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1955, 56.

Michael Ann Holly, “Iconology and the Phenomenological Imagination,” Ikon 7, 2014, 7–16, for debates on the presence of artworks in the moment of the historian versus their own history.

Ram Gopal, Rhythm in the Heavens: An Autobiography. London: Secker and Warburg, 1957, 27.

Uttara Asha Coorlawala, “The Sanskritized Body,” in Dance Research Journal, vol. 36, no. 2 (Winter 2004), 50–63. For the history of Bharata Natyam, see also Matthew Harp Allen, “Rewriting the Script for South Indian Dance, in The Drama Review, vol. 41, no. 3 (Fall 1997), 63–100; Saskia Kersenboom, “Ananda’s Tandava: ‘The Dance of Shiva’ Reconsidered,” in Marg, vol. 62, no. 3 (March 2011), 28–43; Devesh Soneji, Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Edward White, The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

Jonathan Weinberg, “Boy Crazy: Carl Van Vechten’s Queer Collection,” in Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 7, no. 2 (1994), 25–49.

Hari Krishnan, “From Gynemimesis to Hyper-masculinity: The Shifting Orientations of Male Performers of South Indian Court Dance,” in Jennifer Fischer and Anthony Shay (eds.), When Men Dance: Choreographing Masculinity Across Borders. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, 378–91 (quotation 378).

Ann-Marie Gaston, Bharatanatyam: From Temple to Theatre. New Delhi: Manohar Publications, 1996.

Peter Wollen, “Salome,” in Paris Manhattan: Writings on Art. London and New York: Verso, 2004, 101–12.

Kathryn Hansen, “Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre,” in Theatre Journal, 40.2 (May 1999), 127–47 (140). See also Kathryn Hansen, Stages of Life: Indian Theatre Autobiographies. Raniket: Permanent Black, 2011.

Joan L. Erdman, “Performance as Translation: Uday Shankar in the West,” in The Drama Review: TDR, vol. 31, no. 1 (Spring 1987), 64–88.

Sunil Kothari, Photobiography of Rukmini Devi. Chennai: Kalakshetra Foundation, 2004.

Ann R. David, in “Spectacle or Spectacular? The Orientalist Imagery in Indian Dance Performance in Britain from 1900–1950,” Dance and Spectacle, Society of Dance History Scholars (SHDS) 2010, 85, mentions many dancers, such as La Meri, Ruth St. Denis, and Nyota Inyoka, a dancer of mixed Indian and French parentage known in Paris for her “Dances of Ancient and Modern India and Egypt.” Egyptomania in Hollywood is exemplified in Cleopatra (1934), directed by Cecil B DeMille, whom Ram Gopal met soon after his ship from Tokyo landed in Los Angeles.

The role of Ruth St. Denis’s Indian tour on the reform of Indian dance is another story but it points to the global network that manifested in different ways in the early twentieth century, of which Ram Gopal’s is also a strand. See Uttara Asha Coorlawala, “Ruth St. Denis and India’s Dance Renaissance,” in Dance Chronicle, 15.2 (1992), 123–52.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, “Cosmopolitan View of Nietzsche,” in The Dance of Siva: Fourteen Indian Essays (1924). New York: Gordon Press, 1975, 118.

Melissa Ragona, “Ecstasy, Primitivism, Modernity: Isadora Duncan and Mary Wigman,” in American Studies, vol. 35, no. 1 (Spring 1994), 47–62.