Photography as State Apparatus: Resident Registration Card Photography in South Korea

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

This essay is about a seemingly meaningless form of photography that has been practiced in South Korea for the last five decades. Although it exerts a huge power, its significance has never been noticed. I am talking about the photographs found on the resident registration cards (or national ID cards) that are issued to all South Korean citizens over the age of seventeen.

The resident registration card system is a dreadful machine that grasps the crucial personal information of all the people of South Korea. The photograph on each card is very small and too vague to verify someone’s identity, yet it is very important, in that it is one of the primary guarantors of every South Korean’s citizenship. Despite numerous controversies over the resident registration card system as a form of state surveillance, almost no questions have been raised regarding the function and legitimacy of the photographs within it.

The small, seemingly innocent format of the South Korean national ID card photo has its root in the early-modern paradigm of handling visual data.[1]

Following the invention of photography, the frontal portrait, combined with administrative systems of filing data (both visual and textual), began to be used as a form of visual surveillance. Photography attained unprecedented social power at this time. The authority of the ID card photo lies not with the power of the visual, however, but with the nationwide system of registering data about each person.

Thus, among the many photographs produced and consumed in South Korea, in areas as diverse as fine art, science, and commerce, there is no category of photograph more significant than the resident registration card photo. Compared to the fine-art photograph, which is heavily laden with meaning but marginal in its function, the resident registration card photo is almost completely devoid of meaning but functions in a very important way.

The argument that the resident registration card is the most significant form of photography in South Korea might be too bold, but this audacity is the result of my discontent regarding the lack of critical response to it. In public discourse, numerous arguments have been made about the legitimacy of this card, but there is no serious study of the role of photography in it.[2]

One of the reasons for this silence is that the card system has been taken for granted for a long time. South Korean people rely heavily on it to prove their identity as proper citizens of the nation, and they use the card for numerous practical purposes: at the bank, at the hospital, at government offices, and so on. The resident registration number works like a key to all the essential information about each individual.

A resident registration card consists of a photograph; the person’s name, address, and registration number; the name of the issuing organization; a stamp; and a hologram that prevents fraud. Compared to the textual information, the photograph seems innocuous; what we find here is only a frontal view of the face of a person. But this photograph has to follow a strict set of administrative regulations:

- Only a white, uniform background is permitted.

- The subject must stare straight ahead.

- No hair may cover the forehead.

- Both ears must be visible.

- No hat, scarf, or eye patch may be worn.

With these regulations, the photo produces docile bodies. The ID card has a double function: for the benefit of and for the suppression of South Koreans. The dual meaning of recognition — both honorific and repressive — comes full circle here. In this system, each citizen is recognized as a proper subject of the nation. That is why the resident registration system has been accepted by almost all South Koreans without serious resistance.

But the process of identification has also involved the unpleasant experience of inspection by the state. In the past, the police would stop anyone on the street and inspect his or her resident registration card. Thus, South Korean people had to live with the prospect of this inspection without knowing when and where it might happen. Under these circumstances, “the identity of the resident can be maintained only when the person could pass the inspection of the state.”[3]

However, a photograph by itself is not a guarantor of one’s identity. On a practical level, it is not possible to identify someone with only the aid of photography. Seen as a single image, the ID photograph is very weak proof. It is too small and vague to identify someone. Furthermore, the appearance of a person, which is the basis for visual identity, has these days become quite fluid. Changes in hair color, plastic surgery, and piercing have become so common among young people that a small photograph is not enough to anchor their identity. Here photography is just an auxiliary function to the textual information in the card.

In addition, the resident registration card photograph was prone to fraud. Before the year 2000, a photographic print was inserted in the card and a stamp was imprinted on it as a guarantee of authenticity. But as this type of card was easy to counterfeit, a different method was devised. In 2000, the South Korean government altered the technology: the image became a physical part of the card. A hologram on the image works to prevent fraud, as the stamp did in the previous system.

However, the photograph in the resident registration card is still far from perfect. Its resolution is too low and it is difficult to identify someone’s face.

Dating back to the resident surveillance system imposed by the Japanese colonial regime (1910–45), the current form of the resident registration card emerged at the juncture of the cold war and the consequent conflict between South and North Korea. After more than one hundred North Korean guerrillas invaded South Korea in 1968, the South Korean government decided to install a system to identify all the residents of the country, and reinforced the resident registration system in order to pick out North Korean guerrillas, spies, and sympathizers. In 1968 a resident registration card, with a photograph, was issued to all South Koreans over the seventeen and every member of South Korean society came under state surveillance. Everyone was to carry the ID card at all times and present it to the authorities whenever required, so that the police could identify the person and make sure he or she was not dangerous.

In the year 1968, along with the rapid industrialization of South Korea, the urban population drastically increased. Thus, in addition to the threat from North Korea, the South Korean government had to deal with the internal chaos of the exploding population. In this context, Kim Young Mi connects the establishment of the current form of the national ID with mobility within urban areas. “[A]long with the urbanization and the increase in social mobility,” she argues, “abundant discrepancies emerged between the birth places and the current addresses of individuals, and a need for a rapid and efficient control of the residents arose.”[4]

Regarding the historical origin of the resident registration card system, ommentators agree on the importance of certain historical junctures, such as the Japanese colonial period and the Korean War.[5] Through these times of turmoil, the resident registration system was implemented for the purpose of picking out “impure” members of the public. The state well understood the utility of photography as a modern medium. And the card system has been such an effective means of governance that it is still in use after sixty years, in spite of much criticism of its problematic roots in dictatorship and colonialism. The photographs in this card system demonstrate the attitude the modern state wants from its people: docile, fit to the frame, and accurately manageable.

It is a huge irony that the identity of the citizen is based on a surveillance system, but there is something more important than that: the state’s attempt to control and regulate the forms of the portrait.

In South Korea, the late 1960s and the early 1970s was the period during which, in conjunction with the expansion of global capitalism, mass culture began to proliferate. At this time, the Five-Year Economic-Development Plan, led by the dictator Park Chung Hee, brought about dramatic economic growth that resulted in an explosion of commercial photographs and movies. Through the ID system, the government tried to contain the chaos of images by regulating the format of portrait photographs.

Before this period, the faces in portrait photographs, mostly family pictures, were solemn and expressionless. The master photographer Lim Eung Sik said taking a family portrait had been a very important tradition in his family, a ritual that took place only a few times a year. Every family member dressed up and marched to the studio for what was always an austere portrait.

The price of photography before the 1960s was expensive, so a family’s opportunities for having a picture taken were limited. Thus, one simply could not display a frivolous expression at will, using this costly commodity.

Things changed in the 1970s. South Korea’s consumer market expanded quite rapidly, as did the mass circulation of photographic images. Portraits were no longer a rare and solemn ritual; rather, they became an enjoyable experience.

But the dictatorship still adhered to austerity in visual expression. On the streets, police stopped men with hair that was too long (they even cut long hair on the spot) and women whose skirts were too short — and issued fines. More notorious, however, was the censorship of mass culture. For example, a song or movie was censored if President Park did not like any part of it. The criteria for censorship were arbitrary. Under these circumstances, the government felt the need to regulate the most formal portraits of the nation. It reminds one of what Sekula has termed a “battle between the presumed denotative univocality of the legal image and the multiplicity and presumed duplicity of the criminal voice.”[6]

Although the purpose of resident registration card photography was full-scale surveillance over all the people of South Korea, it is a mistake to consider this practice only as a “ wholly negative, repressive power.” ID photography functions as a symbolic order to which one has to submit in order to become a proper citizen. It is a typical modern apparatus of governance, which simultaneously honors and suppresses the individual. That is how the modern subject in South Korea has been born: out of irony and conflict.

Yet these subjects never considered it problematic that the state is keeping the faces of every individual so that it can readily appropriate them. Only recently, together with the heightened awareness of human rights, have questions begun to be raised regarding the legitimacy of the resident registration card system. As Kim argues, “[T]he imposition of identification numbers with personal data on all the members of the nation, the state’s monopolization of this data, and the finger printing practice that regards all the people of the country as potential criminals are considered to be a case of human rights abuse.”[7]

The resident registration card can be seen as an example of what John Tagg has aptly called “ignoble archives.”[8] Small, humble portraits of people are gathered by the state and form an archive that can be utilized for whatever purposes the state wants.

Any Korean photographer seriously concerned about portrait photography cannot deal with the image of a person without questioning this card system, which is the primary way of determining his or her identity. However, it is surprising that although the resident registration card is the predominant way of constituting someone as a proper citizen, only one photographer has dealt with this matter. It was the late Kim Young Soo who challenged the national ID system. Boldly claiming that the resident registration card system should be abolished, he interpreted this card in his own montage work.[9]

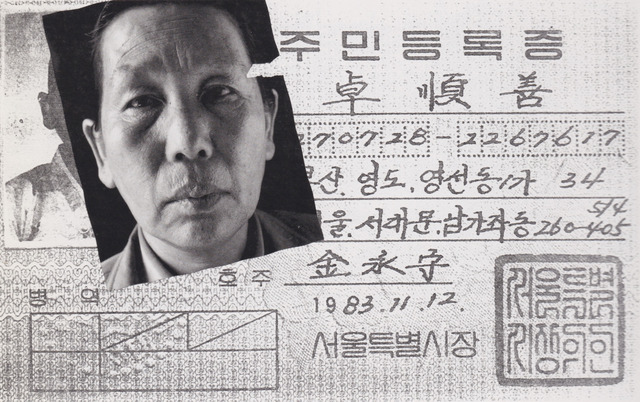

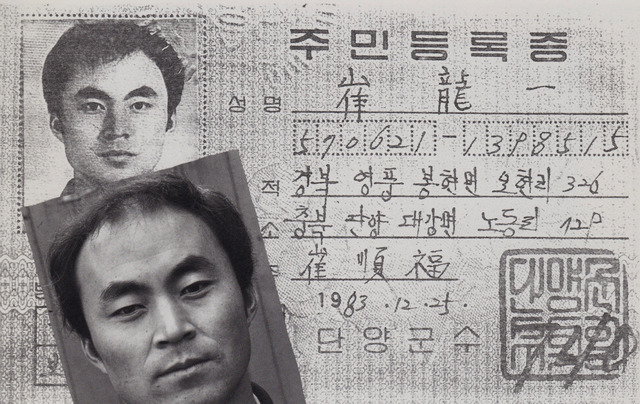

A firm believer in the traditional mode of black-and-white straight photography, Kim Young Soo deviated from his method and ventured into an experimental mode of photography to convey a critical message about the system of meaning wrongly used. With the series simply titled “Human,” each work is composed of a roughly photocopied resident registration card together with Kim’s portrait of the person represented by the card. The photograph as part of the card is small and grainy. What gives authority to this image is not the power of photography but instead a government seal imprinted on it to assert the authenticity of the photograph.

A portrait of the same person taken by Kim Young Soo in a very meticulous manner is superimposed on the card. By keeping the card’s frontal format and empty background, it looks as if he was following the rules. However, what he did was an attempt to disrupt the authority of the government ID system by putting his own photograph in the place where this authority was performed. He did his best to capture all the telling details of the face of a person. A fine black-and-white photograph, this portrait seems to deny the authority of the crude ID card. Some of Kim Young Soo’s photographs are entirely superimposed on the ID card photographs, some partially cover it, and others are upside down. Many of the subjects of Kim Young Soo’s photography are artists. His effort to capture their faces and put them in relation to the national ID cards could be interpreted as trying to revive, in an artistic form, the symbolic lives of people who are oppressed by state power.

Four decades after these works were shown, there still is no response to the exercise of state power to amass the portraits of all its people. Still the questions remain: Who has given the state the right to amass all the portraits of the country? What does it mean for it to make a “rogue’s gallery” out of all these portraits?” What will be its consequences? Is it possible for an individual to understand the meaning of this archive? And does he or she have the right not to submit his or her portrait?

South Koreans are extremely concerned about their faces. There are abundant plastic-surgery clinics, especially in the Gangnam area of Seoul. If only a fraction of people’s concern about the beauty of their faces were directed to the state gallery of South Koreans, inaccessible to its subjects, the meaning of the resident registration card would never be the same.

Lee Young June, also known as <machine critic>, teaches contemporary art at Kaywon University of Art. Recent publications include Pegasus 10000 Miles, a book about a journey on board a containership, and Machine Flaneur, a collection of essays on machines. Recently he organized an exhibition entitled “Space Life: Images from the NASA Archives” at the Ilmin Museum of Art in Seoul.

References

- Hong Seong Tae, “The Yusin Dictatorship and the Resident Registration System in Korea,” in Critical Review of History, May 2012.

- Kim Young Mi, “Changes in the Resident Registration System and the Characteristics Thereof — Historical Origins of the Resident Registration Card,” in Journal of Korean History (136), March 2007.

- Kim Young Soo, Human 2 (Sigag: Seoul, 1987).

- Sekula, Allan, “The Body and the Archive,” in October, vol. 39 (Winter 1986).

Notes

In 1879, the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon developed an anthropometric system of measuring and recording body parts, especially faces. Since then, police in many countries have employed the Bertillonage system to build archives of the records of criminals. The core of this system is the combination of portrait photography and text. Because a photograph provides only mute testimony, it needs the assistance of textual information — name, date of birth, sexuality, and address, for example, in order to function as a regulatory tool.

Recently, after the resident registration number worked like a key to leak the personal data of a staggering amount of the South Korean population, leading to all kinds of crime, the general public became alert to its uses. As a result, it has been replaced by a different identification number system.

Kim Young Mi, “Changes in the Resident Registration System and the Characteristics Thereof — Historical Origins of the Resident Registration Card,” in Journal of Korean History (no. 136), March 2007, 297.

See Kim Young Mi, “Why Has the Resident Registration Card Come About?” in The History Open to Tomorrow, September 2006, 143; and Hong Seong Tae, “The Yusin Dictatorship and the Resident Registration System in Korea,” in Critical Review of History, May 2012.

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” in October , vol. 39, Winter 1986, 6.

John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1993), 127.