More Than a Collection: Photography in the Asia Art Archive

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

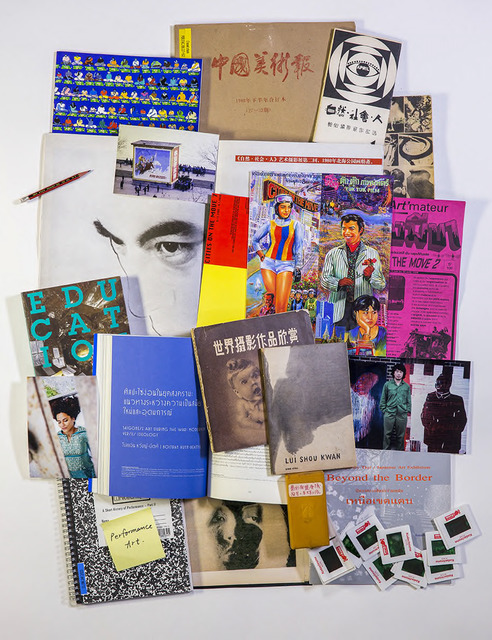

Fig. 1. Exhibition view of Excessive Enthusiasm: The Ha Bik Chuen and the Archive as Practice, March 11 – July 3, 2015, Courtesy of Asia Art Archive.

Fig. 1. Exhibition view of Excessive Enthusiasm: The Ha Bik Chuen and the Archive as Practice, March 11 – July 3, 2015, Courtesy of Asia Art Archive.Although the Asia Art Archive fosters one of the most prominent collections of primary and secondary source material on contemporary art in Asia, it is no mere storehouse. Rather, the archive is a live site and catalyst for active critical inquiry. Through its various research activities and public programs — such as symposia, artist talks, screenings, and lectures — AAA has become a platform for dialogue and critical thinking, thereby facilitating significant reevaluations of art historical narratives of the region. Starting with a single bookshelf in Hong Kong in 2000, the Asia Art Archive now houses more than fifty thousand records comprising hundreds of thousands of physical and digital items and is still growing. This extensive collection ranges from books, artist’s sketches, exhibition ephemera, and rare periodicals to individual personal archives. That single bookshelf is now AAA’s enterprising headquarters in Hong Kong, a research center and library where you can view physical records as well as digital material restricted to on-site access due to copyright concerns. Outfitted with large sunny windows, a self-help photocopier, computers, and free Wi-Fi, it provides a welcoming and relaxed environment conducive to leisurely browsing and study. Open to the public year-round and free of charge, it forms the nucleus of the organization with satellite centers in New York City and New Delhi.

The organization plays a vital role in restoring and preserving the collective memory of contemporary art practice in the region. Because of a lack of proper infrastructure and preservation sensibilities, a lot of primary source materials are either lost or irretrievably damaged. With diligence and urgency, through research teams working steadily — in Beijing, Hong Kong/PRD, Manila, New Delhi, Seoul, Taipei, and Tokyo, to name a few — the archive salvages, preserves, and strings together the scattered documentation of recent art activity in the region. Moreover, many of these records have never been made public before. It is only by AAA’s active pursuit that they will now be freely accessible or, as Elaine Lin, the collections manager, puts it, “AAA makes the invisible, visible.”

Although 85 percent of its content is built from material donations, the archive firmly upholds a policy of “preservation through sharing” and thereby gladly accepts digital copies of material held elsewhere. Says Lin: “[D]igitization also means you don’t have to colonize everything — uproot it from [its] place of origin.” In fact, to promote shared knowledge as well as to avoid duplication, it proactively maps complementary resources from other organizations. A major digitization initiative started in 2010 further realizes AAA’s goal of shared information by providing a wider audience with multiple points of entry into the collection. Much of the result can be viewed through its Collections Online platform and is only one of the many ways in which the archive demonstrates its commitment to broaden the critical discourse on contemporary art in Asia.

The Asia Art Archive’s posture of critical enquiry is remarkable in that it is not simply projected outward but is also introspective. One of the ways in which this is manifest is how it navigates its involvement with photography. Out of the seventy thousand records existing online, some five thousand relate to photography: in books, periodicals, exhibition catalogues, and primary source materials related to photography events and exhibitions. Moreover, because large parts of its collection are preserved through digitization, the archive deals heavily in images. For example, it is almost impossible to retrospectively view a record of performance and site-specific installation art without the lens of photography. In addition to such documentary material, AAA houses huge caches of photographs from personal archives captured by art practitioners whose work falls either partly or fully into photographic practices. Of these, the archive asks: “At what point does a photograph become visual art?”

The question is echoed at various points of AAA’s collection and research history. Recently, the archive invited the curator, writer, and artist Zhuang Wubin to explore the malleability of the boundary between the photograph as document and the photograph as art. Another recent invitee of AAA’s residency program, Amelia Jones, presented her perspective on the ways in which performance can be documented and addressed the technical and philosophical complexities that are embedded in the relationship between performance art and photography.

Speaking specifically about AAA’s material from China, Anthony Yung, a senior researcher at the archive, tells us that this question is being asked in the region in general. He reminds us that “photography in China is a special medium. In the art academy system, it was never considered as fine art until the 1990s.” Through its collection of general-survey and special-topic books, exhibition catalogues, and the rich variety of primary source material, AAA does a thorough job of tracing the evolution of photography as an autonomous art form. This narrative arc is further illustrated by the curatorial project directed by its 2014 research grant recipient, Chen Shuxia. By focusing on the April Photo Society, a seminal group of photographers that emerged in the late 1970s, Chen maps the transition in Chinese photography from the Mao era’s Socialist Realism to an experimental approach fueled by the desire to depict social reality. Yung points out that the group also plays a crucial role in constructing the collective memory of the region, as it is through its extensive documentation at a time when the camera wasn’t a common household commodity that one gets rare glimpses of the city.

Another collection of material situated at this juncture of mapping histories and expanding discourse in the region of China is the Ha Bik Chuen Archive. Upon his death, Ha Bik Chuen’s family opened the doors of his studio to AAA, revealing full walls of photographs and studies. Known for his sculpture and printmaking, Ha Bik Chuen’s vast collection of exhibition catalogues, magazine and newspaper cuttings, collage books, and photographic records of the Hong Kong art scene betray parallel practices in photography, collage, and archiving. In assessing the high photographic content of this archive, AAA once again finds itself contemplating the intersection of photography as documentation and photography as art. The collage books expand the dialogue about print media, specifically the printed photograph and its recontextualization. This conversation is further amplified by Collage Party, an experimental project directed by recent artist-in-residence Paul Butler, who responds to Ha Bik Chuen’s collage books by inviting people to navigate large volumes of found printed material and create art together in a social setting.

Equally potent caches of photographs can be found in AAA’s collection of material on India, specifically Vivan Sundaram’s Re-Take of Amrita and Jyoti Bhatt’s Living Traditions. Profoundly significant in its art historical value, Re-Take of Amrita is a series of haunting photomontages in which Sundaram renegotiates his personal history by digitally manipulating family photographs from the Sher-Gil archive. Simultaneously, he provokes the world’s reimagination of the two iconic figures who appear repeatedly in the work and serve as indexical references to the historic confluence of modernism, nationalism, and multiculturalism in India, all pioneers in their fields: his aunt, the legendary painter Amrita Sher-Gil, and his grandfather, the photographer Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, whose photographs form the bulk of the original archive. Located in Another Life: The Digitized Personal Archive of Geeta Kapur and Vivan Sundaram, one may viewed it in the wider framework of his long-term preoccupation with the Sher Gil archive as well as his other involvement with photography.

Living Traditions, on the other hand, is a comprehensive photographic record of traditional art and craft forms of India. Starting in 1967, the renowned painter, printmaker, and photographer Jyoti Bhat, traveled extensively across the country, meticulously recording the various creative processes. These ranged from floor to wall practices, methods, techniques, and even the daily unfolding of life around them. Indispensable as records of the history of Indian art, the “decisive moments” within these photographs charge them with such narrative potential that they’re immediately granted dual status as document and art. These have been digitized and arranged on the AAA site in a manner that is identical to Bhatt’s own organization of storage boxes and contact sheets. A collection of almost thirty thousand photographs accompanied by copious notes, Living Traditions is only one small part of the Jyoti Bhatt archive. In it also are photographs he took over the years of the faculty and development of the Baroda School of Arts. In addition, Bhatt’s diaries, sketchbooks, designs, and writings have been made accessible online for the very first time on AAA’s website. The challenge then lies in the curatorial demands of such a huge collection of material: How do you present such a large body of work? What might be the most conducive entry points and how do you design them? To address these concerns, and as part of its broader interest in investigating the very concept and possibilities of the archive, AAA recently facilitated an Archival Fellowship in collaboration with the India Foundation for Arts. The winning project, by Vinod Velayudhan, aka Chinnan, explores various configurations of Bhatt’s archive through a process of “data-visualization.” Velayudhan’s prototype will be available on the archive’s website and all the programming codes will be kept open-source.

To further explore the curatorial possibilities in approaching the archive, AAA invited the artist Shilpa Gupta to explore and interact with its India collection. By mapping connections between documents on art institutions, artist-run spaces, exhibitions, and publications from the 1960s through the ’80s, Gupta wove stories around the various protagonists of this history. Titled That Photo We Never Got, the resulting installation extended these narrative trajectories beyond the archive by way of photographs, documents, and snippets of conversations that Gupta brought in from outside. Suggesting histories of love, friendship, associations, and incongruities, some imagined and others real, it is a poetic rendition that also examines the relationships between photography, narrative, and archive. The project has been exhibited at the India Art Fair, the AAA library in Hong Kong, and an exhibit in Mumbai, where it was shown alongside two other photography projects.

Naturally, the spatial demands each location made on the presentation differed greatly. Moreover, to create the exhibition, Gupta made prints of material the archive had previously digitized. An interesting feedback loop is generated as AAA contemplates the best ways to transfer these reimagined pieces, along with the context of each exhibition location, back into the digital archive. The archive also participated in a panel discussion around the Mumbai exhibit, which was called Access T:me, to explore the various ways in which art, photography, and archives intersect. According to senior researcher Sabih Ahmed, this initiative reflected questions the archive was already asking: “What is the relationship between memory and forgetting? What is the relationship between art and photography? What is the role of the gallerist who has to deal with the photograph and the archive?”

These are only a few examples of AAA’s collections and activities centering on photography in China and India; the scope of the archive is much wider. To explore and activate this vast collection, AAA offers several research grants and fellowships in addition to hosting a residency program. The grants provide resources to conduct focused research projects in the region while simultaneously introducing new materials that address gaps in the archive. The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Research Program, for example, awards up to three individuals yearlong grants for researching contemporary Chinese art using the archive. The top grantee is awarded $15,000 and is expected to spend two months on site at the AAA headquarters in Hong Kong in addition to any fieldwork that might be relevant. Up to two runners-up are awarded $5,000 for their projects. The London, Asia Research Award encourages inquiry into the institutional histories and cultural connections between London and Asia across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. There is also the inaugural SSAF-AAA Research Grant, resulting from a recent partnership with the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation, which focuses on cultural periodicals from one or more languages or regions. And AAA’s Residency Programme invites artists, researchers, curators, and creative practitioners to engage with its collection, philosophies, and sites. The residencies have flexible timeframes and promote multidisciplinary interaction, thereby producing diverse outcomes. All of this information as well as open calls are announced on the archive’s website, on social-media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WeChat), and in their eNewsletter. A list of its current and upcoming programs, calls for papers and participation, talks and workshops can also be found more specifically on the website’s program page.

Never resting in its spirit of critical investigation, the archive also generated an online publication called Field Notes. From 2002 to 2012, this publication was produced under the title Diaaalogue. From 2012 to 2015, Field Notes invited the art community to contribute articles on select themes. For its anniversary program, 15 Invitations, AAA employed Field Notes as a blog to trace the developments of the fifteen participating artists and cultural practitioners. In AAA’s revamped website, Field Notes and Diaaalogue are now incorporated into the new online publication, Ideas. Each Monday, Ideas publishes new essays, interviews, and curated journeys through AAA’s research collections.

In reimagining this new website, the archive has been mindful of creating multiple entry points that might be conducive for the navigation of such a vast collection spanning an equally wide geographic range. It is also sensitive to the multiple hats twentieth-century artists wore — those of teacher, social documentarian, organizer, trailblazer — and their artistic journeys as they challenged barriers between disciplines and around traditions. Speaking of the exceptional collection of photographs documenting the artist-run workshops at the Kasauli Art Centre, in India, AAA researcher Sneha Raghavan says, “The archive wants to ensure that these narratives are captured when this material is presented.” Referring also to Kasauli, this time in relation to the artist-run spaces that are currently emerging, Ahmed asks: “How do you create a field rather than enter one? Kasauli is testament to that and these photographs are bringing it back into our imagination . . . let’s not forget. The archive has nostalgia value, but it also has propositional value.”

Given how the Asia Art Archive strives to initiate critical consideration in all its work, this view can be easily extended to the entirety of the organization.

Born and educated in India, Procheta Mukherjee Olson is an artist, writer, and curator currently completing her MFA at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. As the 2015-16 Annual Curatorial Fellow at the University Museum of Contemporary Art she co-curated the exhibit Eyes Are For Asking: Narratives in Photography. She is the 2016-2017 Five College Intern at the Trans Asia Photography Review.