Ali Behdad, Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East

(Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015). 224 p.

ISBN 9780226356402

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Salvaging the Paradigm

The theme of Orientalism, notwithstanding a plethora of critical reflections, continues to provide a framework for critiques of power. Deploying Orientalism to the field of photography, Ali Behdad, in a conceptually stimulating and suitably illustrated book entitled Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East, builds a multi-textured argument about the relationship between photography, the Middle East, and Orientalism. The study shows how and why “Orientalism matters” in thinking about photography in/of the region. The early “science” (and later, contemporary art) of photography is linked, by way of a range of examples from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-2000s, to the politics and industry of exoticism. The author’s task, as he explains in his introduction, is to “insist” that Orientalism “remains a crucial perspective from which to comprehend the meaning and significance of photographic representations of the Middle East.” Behdad achieves this in presenting a well-researched and contextualized series of photographs, coupled with, throughout the book, a self-aware critical reflexivity about the concept’s shortcoming. But how — and how persuasively — does the book carry through its arguments that “Orientalism (still) matters”?

Camera Orientalis is divided into five chapters, each addressing a distinct (but related) aspect of Orientalism with refreshing arguments that emphasize hybrid practices and multidirectional gazes. Behdad places the Middle East at the center of early photographic history; a region, he explains, filled with “optimum light” for photographic exposure and development. This is a welcome scholarly foregrounding, particularly given the challenges of conducting research on early photography from the region, such as lack of access, destroyed and/or incomplete collections, and generally limited sources. Without promising to prove a comprehensive history of photography in/of the region (the early history of photography focuses on the nineteenth, as well as the early twentieth century; the contemporary art photography is drawn from the 1990s and early- to mid-2000s), the book offers a series of compelling insights into the social lives of various sets of photographs and their rooting in ideologies and aesthetics of power.

The book’s title makes a conscious theoretical double nod: to the famed treatise on photography by Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (1980), and, more closely in its conception, to Christopher Pinney’s Camera Indica (1998) — a book that itself alludes to Barthes’s work in its title. Both of these earlier works examine the ontology of photography, respectively setting out to dispel various assumptions about what photography is/was. As an anthropologist studying photography in India, Pinney supersedes Barthes’s emphasis on the private realm of photographic meaning(s), illustrating how social and political context matters in the production and consumption of photography. Pursuing this line of inquiry in Camera Orientalis, Behdad develops his argument that Orientalism matters in photography in/of the Middle East. What is distinctive about Behdad’s work, as a literature and postcolonialism scholar, is his decidedly conceptual and transcultural approach to studying photography beyond the nation-state.

In a theoretically punchy introduction, Behdad defines his version of Orientalism: neither a pristine concept, nor in strict accordance with Edward Said, but rather a “network of aesthetic, economic, and political relationships that cross national and historical boundaries” (p. 19). This notion complements the author’s equally network-focused definition of photography as a “phenomenon of contact and travel.” Early in the book, bringing photography and Orientalism together, the author cites both phenomena in constructing “the idea” of the Middle East as an exotic entity and a (tourist) imaginary. For Behdad, the Orient as imaginary is constructed and fuelled by images. Although some of this imagining is attributed to other semantic forms, such as European painting and travel writing, Behdad’s analogy attends specifically to photography. He details, along with several other findings, how photographs of the Middle East held particular currency in the tourist markets of Europe. The photograph, he suggests, and its scientific claim to realism, came to heighten the traveller’s imaginary desires for “the Orient,” which in turn helped to grow “the idea” of the Middle East throughout the West. These arguments, put forward in chapters 1 and 2, are adeptly deployed via a range of photographic examples from across the region, drawn from archival research undertaken by the author. This early emphasis on imaginaries makes for a captivating opening to the book, and speaks to the ensuing chapters’ closer examination of image sets.

In chapter 3, the phenomenon of resident foreign photographers in the Middle East during the nineteenth century is examined through the case study of the renowned Georgian photographer Antoin Sevruguin. Behdad acknowledges that Sevruguin’s photographs indicate a sympathetic reflexivity and cultural insight indicative of one who has lived in a country (Iran) for sustained periods (as Sevruguin did). At the same time, the author concludes that Sevruguin ultimately “could not occupy a position outside of Orientalism and colonial relations of power to produce a nonexoticist vision of Iran” (p. 98). The analogy here drives forward the theoretical argument of the book, even as it raises many relevant points about this controversial body of work.

Chapter 4 draws on photographic material from private collections, among them the author’s own family archives. One of the sets of photographs discussed is a striking series of images from Parisa Damandan’s collection of vernacular photographs from Isfahan, such as Iranian prostitutes from the 1920s–’30s, appearing dressed in Western clothes and posing in front of European backdrops. In the examples discussed in this chapter, Behdad focuses on what he terms “(Self-)Exoticism.” Briefly, the idea is that images from the region during this period demonstrate local forms of photo-exoticism that were simultaneously in visual dialogue with European, Orientalist perceptions of it.

Of the many examples the author cites to flesh out this idea is a series of photographs of nude Iranian women, ca. 1900s, obtained from the private collection of a prominent (anonymous) Iranian art historian based in Tehran. Behdad claims these images, as local pornographic photography produced by and for Iranians, represented a distinctly male Muslim Iranian fantasy of androgyny that spoke to indigenous standards of beauty, in addition to forbidden eroticism (p. 112). At the same time, such images, Behdad suggests, were also in dialogue with European aesthetic conventions of exoticism, materially and formalistically. Unlike Ottoman-era photographic studio practices however — which the author claims followed more closely the European conventions of harem representation in catering mostly to European tourist markets — indigenous Iranian photography is hereby shown to entail local “transculturation”: a process of translation by which photographs were simultaneously in “close dialogue with Orientalism as a style of representation” and “made desirable legible and useful for a local audience” (p.111). Photographs, after all, as commodities, were produced for local consumption as well as for European tourist markets.

The notion of “Orientalist Transculturation” Behdad introduces in this chapter moves away from simplistic understandings of local photographic practices in the Middle East mimicking European artistic convention. Instead, what is suggested here, and in the book as a whole, is a process of “grafting” — that is, an intertextual and intervisual blending of European and, in this case, Iranian-Qajar conventions, through which middle- and upper middle-class individuals fashioned an indigenous form of modernity rooted in local traditions. The concept moves beyond established postcolonial binaries of center/periphery and power/resistance toward a more nuanced exegesis of photography in/of the Middle East as a “contact zone.”

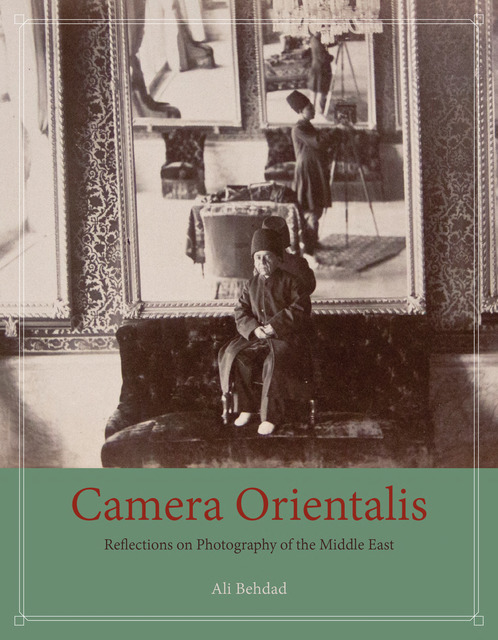

Chapter 5 turns a critical eye on local representations of power in Royal Portrait Photography in Iran. Here an emphasis on the materiality of portraiture — an anthropological regard for the portrait as a social object — is foregrounded in explaining local dynamics of power and inequality. The emphasis in this chapter on sociopolitical context extends beyond a certain art-historical tendency, identified by the author, to treat photographs as “aesthetic objects.” Concurrently, the in-depth regard for what the images show (and do not show) renders these photographs — and their social lives — significant from multiple angles. In particular, the widespread absence of women in these photographs, as is also the case in the author’s family collection, discussed in chapter 4, marks an important indicator for Behdad of social inequalities and mores that photographs are able to expose.

The afterword, titled On Photography and (Neo-)Orientalism Today, doubles as the book’s conclusion and strikes a refreshing contemporary tone. Behdad builds on his earlier historical examples to a carefully extrapolated set of images and practices that bring the Orientalis of his Camera into the twenty-first century. Here, in a theoretical finale, Behdad introduces the notion of “neo-Orientalism” — a modern-day mutation of the various Orientalist logics exhumed throughout the book, as seen in the work of contemporary artists — and the significance of photography in global geopolitics. Behdad illustrates how socially engaged art works by Middle Eastern artists (both from the region and in diaspora), particularly concerning social and political inequalities faced by women, are deemed by many a Western art curator and audience to be “authentic” beacons of “light” against the backdrop of the “dark,” oppressive, backward, and undemocratic societies from which they are considered to have sprung.

In turn, and in tune with post-9/11, “War on Terror,” “Western” neoliberal discourse, these societies, and especially their women, appear to be “in need of saving.” As such, in the reclining nudes, harems, “Chador” art, and other visual tropes addressed and replicated, albeit critically, by many Middle Eastern artists, the subtle nuances of these works are, according to Behdad, routinely misinterpreted by Western viewers in ways that are diametrically opposed to the intentions of the artists. The resulting argument from this afterword confirms the author’s conviction outlined in the book’s introduction, namely, that the paradigm has ensued: Neo-Orientalism remains a pervasive ideology of the day. In speaking to the contemporary political “moment,” characterized by contentious ways of envisioning “others,” this closing section of the book appears timely and essential.

Overall, Camera Orientalis presents a marked scholarly contribution to research on, and broader understandings of, the Middle East. The book is a laudable attempt to salvage the paradigm of Orientalism from the threat of epistemological extinction by overuse and/or scholarly abandon. The picture is a rich and complicated exposure of photography, carefully crafted by the author with a cross-disciplinary approach that hints at the multimodalities of power, vision, and framing that accompany the cultural and political history of the region. Reading the book in the contemporary political moment, when (digital) technologies and visualizations continue to be deployed to stake “truth”-claims about “others”, Camera Orientalis, and its author’s insistence that every iota of power be accounted for in unearthing the architectonics of visual knowledge, makes for an important benchmark of understanding.

Shireen Walton is a Teaching Fellow in Material and Visual Culture in the Department of Anthropology, University College London. Among her interests are popular photography, visual and digital culture, and social media/imaginaries in/of Iran, the Middle East and Islamic World.