Clare Harris, Photography and Tibet

(London: Reaktion Books, 2016). 173 p. References, select bibliography, acknowledgments, photo acknowledgments, index.

ISBN: 978 1 78023 652 0

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Clare Harris’s wonderful Photography and Tibet is part of the Reaktion Books Exposures series, which provides introductions to the history of photography related to specific themes and regions. Photography and Tibet accomplishes this in providing a much-needed introduction to the history of photography in Tibet and surrounding regions of the Himalayas. However, Harris gives us much more, as along with this historical overview, she reveals how the history of photography in Tibet can also be seen as the history of the way Tibet has been imagined beyond its borders by Westerners, Chinese, and others, and how this imagining has directly influenced colonial engagement with Inner Asia and the Himalayas.

The popular representation of Tibet as a mystical, impenetrable Shangri-la was born of Chinese imperial policy during the Qing dynasty, which prevented the British East India Company, on the lookout for trading partners, from political and economic overtures to Tibetan authorities under the rule of the Dalai Lamas. Unable to visit the “roof of the world” directly, British imperial representatives were left curious about the region. The earliest photographs of Tibet, which emerged in the nineteenth century, were all by these representatives, and soon after, explorers joined them in their quest to acquire photographs and stories of this little understood spiritual sanctuary in the high Himalayas.

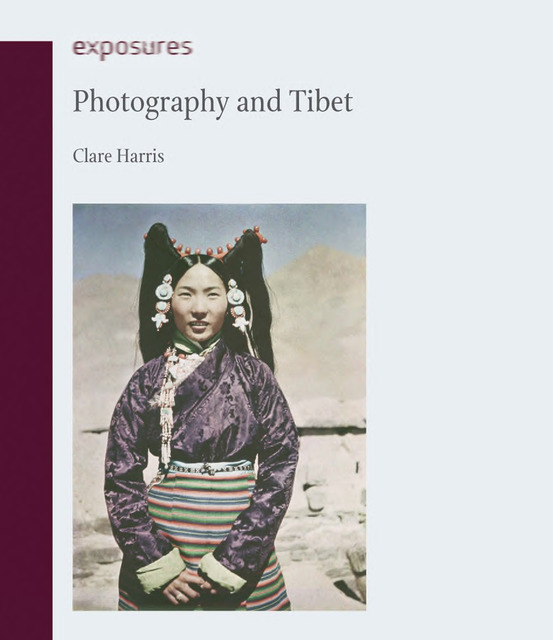

When they couldn’t visit Tibet itself, photographers settled for nearby regions on the borders of British India (especially in Darjeeling) and China, where they sought to photograph individuals who represented “types” and “taxonomies” of religious and ethnic diversity to satisfy the imperial gaze.

Harris’s work introduces us to the different Euro-American colonial officials, explorers, missionaries, spies, and religious aspirants who ventured into the region and returned with remarkable pictures of extraordinary landscapes of mountains, lakes, and grasslands and ornately adorned lamas, aristocrats, traders, and pilgrims, which fueled the public imagination and led to the craze for more pictures. Even today, exhibitions and coffee-table books featuring photographs of Tibetan and Himalayan otherworldly high-altitude landscapes, unique architecture, and monks and nomads do a roaring trade with publishers from places as diverse as New York City, Rome, Shanghai, and Delhi.

Photography and Tibet provides us with a historically contextualized consideration of why Tibet as a photographic subject continues to capture the global popular imagination.

Although this detailed historical overview is much appreciated in itself, what makes Harris’s work even more valuable is her recognition of the fact that the photographic history of Tibet is not a one-sided one of simple exploitative, Orientalist representation of an Other. Harris’s detective work has uncovered the local collaborations behind many of the famous photographs. Rabden Lepcha, for example, was not merely an assistant to the well-known writer and explorer Charles Bell; he and others were the actual photographers of many classic representations of Tibetan culture in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.

The stories of figures within these photographs, too, are not straightforward; images from the photographic studio of Thomas Paar, in Darjeeling, featuring local luminaries such as Sonam Wangfel Laden La, problematize assumptions about the lack of agency in photographs. Evidence shows that locals at times willingly took part in, and were even instrumental to, the staging of these pictures and, by extension, their culture.

The multidirectional histories of photography in Tibet have had enormous influence on global perceptions of the region’s society and politics. In later chapters, Harris turns to consider how Tibetans have responded to photographic legacies by examining the works of Tibetan photographers from the early twentieth century to the present. All of these artists are actively engaged in using photographic mediums to challenge superficial representations of their culture and, in doing so, participate in the creation of new forms of cultural expression. Harris’s careful attention to the multiplicity of agents active in the photographic construction of Tibetan culture is undoubtedly central to the enormous value of this book. As well as exposing audiences to a critical artistic and aesthetic history of how Tibet has been represented through photography, Harris provides crucial historical, cultural, and, perhaps most important, political context to these pictures.

The book is divided into a prologue, three chapters, and an epilogue, all of which correspond to different moments of photographic engagement with Tibet. The prologue begins with the tale of the photograph of two Tibetan warriors in the British soldier and scholar L. A. Waddell’s Lhasa and Its Mysteries (1905) as a starting point for thinking about the contested nature of Tibet as a subject in photography.

The image was intended to demonstrate the warlike, backward nature of Tibetans, thereby legitimating the 1904 British colonial incursion into the region. Actually, however, the picture is of porters wearing their armor (borrowed from a local monastery, where it was used as a ritual symbol) backwards. Harris’s archival work enabled her to discover the original subtitle of the image, found in a book of photos stored in the Royal Geographic Society: “two faked Tibetan soldiers.” The staged nature of this image, and its use for a political purpose in a context far removed from its original creation, represents a key theme in the book: “[T]he archive records a rather different history from that presented in the visual fictions of popular print culture.”

This theme continues in chapter 1, “Picturing Tibet from the Periphery,” in which Harris explores early attempts by British soldiers and officials, such as Philip Egerton and Melville Clarke, to photograph Tibet’s mysterious landscape. When they could not reach Tibet, photographers turned to peripheral areas within the purview of British control to capture representations of the Other. Among these are images taken near Ladakh (by Alexander Melville and Henry Godwin-Austen) and beyond Shimla (by Samuel Bourne). Perhaps the most important “proxy” for Tibet was Darjeeling, in the eastern Himalayas, where photography helped to create colonial taxonomies and also provided exotica for imperial consumption. This section of the book is fascinating, and a vital contribution to the study of colonialism in the Himalayas in its own right. Harris has traced how widely distributed, popular photographs of local culture that have been crucial to the creation of Tibet under the imperial gaze were staged by local photographic studios, owned by practitioners such as Thomas Paar, as well as by scholars and officials such as Sarat Chandra Das.

Chapter 2, “The Opening of Tibet to Photography,” continues the chronology by focusing on British officers, Nazi ethnographers, and Euro-American explorers, among others, who traveled to Tibet. The photographs they took, especially in the ethnographic register, were created with a wide variety of motivations and purposes that contributed to the creation of certain “tropes” in the photographic representation of Tibet. Among the photographers featured in this chapter are the French prince and explorer Henri of Orléans; members of the Younghusband military expedition of 1904, such as John Claude White; the British officer Charles Bell; the Austro-American plant hunter Joseph Rock; the American missionary Albert Shelton; and the American yoga enthusiast Theos Bernard. Harris also discusses female photographers, such as the self-styled mystics Alexandra David-Néel and Li Gotami Govinda. The chapter ends, chronologically, with a new moment of imperialism in Tibet: the inclusion of Tibet within the new People’s Republic of China. This time period led to a trend in the photographic corpus of Tibet: Han Chinese photographers depicted the region “as a Maoist utopia rather than a Buddhist one.”

Chapter 3, “Tibetan Encounters with the Camera,” briefly covers some of these photographers but concentrates on those from Tibet. Despite the very real challenges of putting together an overview of an archive that has been dispersed through exile and partly destroyed through political turmoil, Harris provides an unprecedented introduction to a variety of Tibetan artists and the ways they have gained “control of the camera and representation of their country.” Photographers include the fourteenth Dalai Lama himself and Tseten Tashi, a Sikkimese-Tibetan photographer, based in Gangtok, whose access to the elite in Sikkim and Tibet led him to take amazing and unique photographs of key figures in twentieth-century Himalayan politics and society. The chapter also discusses more recent practitioners, such as Tenzing Rigdol, Tsewang Tashi, Tsewang Dakpa, Nyema Droma, and Jigme Namdol, who are involved in creating contemporary photography that challenges romanticized, essentialized visions of the Tibetan present by depicting the complex realities of Tibetan culture in global settings.

Especially noteworthy in this chapter is Harris’s thoughtful consideration of an indigenous Tibetan philosophy of photography in her discussion of par (Tibetan for photograph, print, reproduction, or copy). In this section, she demonstrates how photographic technology has been embraced as a way to mass-produce images of spiritually powerful figures — reincarnate lamas, for example — as such figures “live beyond the physical and temporal parameters of the moment at which they were recorded by the camera.” The mass reproduction of their images thereby overturns “ruptures created by the passage of time, exile and death,” and therefore has a unique significance in Tibetan Buddhist culture.

In the epilogue, Harris discusses the recent viral wedding pictures of a Tibetan couple in China that represented them in various traditional Tibetan and contemporary clothing, places, and spaces as a way to consider popular Tibetan agency in the present moment of mass Internet distribution and as a way of “mak[ing] Tibet anew photographically.” This conclusion to the book points to the possibilities that photography as a technology allows by the representation of multiple perspectives, thereby overthrowing historically limiting gazes of authority.

Harris’s prose throughout is lively, engaging, and accessible, filled with anecdotes to illustrate her theoretical arguments. As well as being a pleasure to read, Photography and Tibet is a pleasure to look at. Carefully curated examples of the photographers, periods, and themes under study have been beautifully printed in glossy black-and-white and color reproductions. Especially delightful are the postcards from Darjeeling and the selection of more recent photography by Tibetans, which show the spectrum of the complex histories of Tibetan-subject photography.

The book’s portable size as part of the Exposures series means it is ideal for use in undergraduate and graduate classes related to a variety of topics: regional courses on Tibet, the Himalayas, and East, Inner, and South Asia more generally; the history of photography; visual and material culture; and comparative empires and the history of Orientalism. Harris’s book should also find a much greater audience for anyone interested in the region and the intertwined histories of photography and empire. It would also be wonderful to see her amazing discoveries in larger format.

As the recent case of the viral wedding photographs featured in the epilogue demonstrates, the themes of photography and the politics of representation in Tibet and the Himalayas remain vitally relevant. Let us hope that Harris continues her work, providing us with new insights to challenge assumptions about the question of agency in cultural representation.

Amy Holmes-Tagchungdarpa is an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Grinnell College and the author of The Social Life of Tibetan Biography: Textuality, Community and Authority in the Lineage of Tokden Shakya Shri (Modern Tibetan Studies Series, Lexington, 2014). Her research explores the cosmological and material interactions that have shaped the cultures and histories of the Himalayas on a regional and global level.