Ogawa Kazumasa and the Halftone Photograph: Japanese War Albums at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

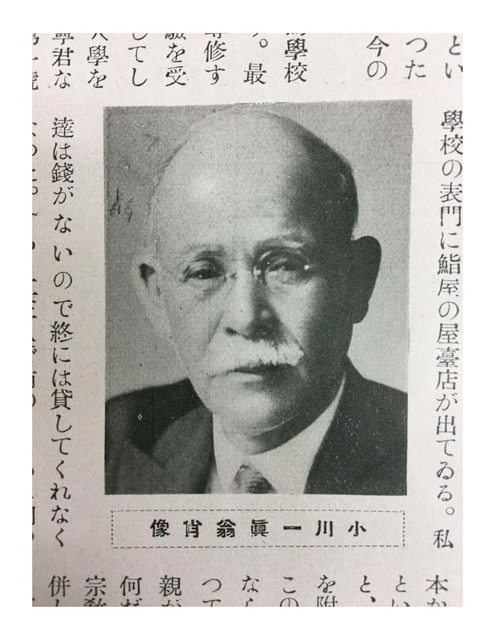

Fig. 1. “Portrait of Ogawa Kazumasa,” in “Ogawa Kazumasa ō: keirekidan. Shashin-shi” (The Venerable Ogawa Kazumasa: A Personal History. History of Photography) Asahi Camera. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, October, 1927: 435.

Fig. 1. “Portrait of Ogawa Kazumasa,” in “Ogawa Kazumasa ō: keirekidan. Shashin-shi” (The Venerable Ogawa Kazumasa: A Personal History. History of Photography) Asahi Camera. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, October, 1927: 435.From October 1927 to July 1928, the magazine Asahi Camera published a series of autobiographical essays on Ogawa Kazumasa (1860-1929), a photographer, publisher, and pioneer of photomechanical reproduction in the mass press. Each essay described Ogawa’s life-long project of introducing and expanding photographic technologies in Japan and showed how, indeed, Ogawa’s story of many “firsts” illustrates the history of Japanese photography at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1889 he became a founding member of the Japan Photographic Society (Nihon Shashinkai), the first photography association in Japan, and in that same year the publishing company he founded, the Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Copperplate Engraving Studio, printed Essence of the Nation (Kokka 国華), which is often described as the first mass produced art magazine in Japan. In 1894 he assisted the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun in using the halftone process to reproduce photographs in a newspaper for the first time, and in that same year, his publishing firm printed the first albums of photographic images of the Sino-Japanese War. In 1895 he was the first Japanese photographer to be named a fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of England. In 1906 he became the first photographer to be honored by the imperial household with the Order of the Rising Sun, and in 1910 he became the first photographer to join the Japanese Imperial Art Academy.[1]

The recognition Ogawa gained amongst exclusive art circles in Japan is an implicit indicator of the gradual acceptance of photography as an artistic practice. In addition, his efforts to expand the use of photography in a range of media – from newspapers to magazines and from albums to popular public exhibitions – transformed the way that people thought of the practical applications of taking pictures as a visual technology. The photographer and engineer, W. K. Burton, whose 1890 account was the first English-language introduction of Ogawa’s life history offered to the international photographic community, described how as a fifteen-year-old, Ogawa wanted to find a way to illustrate books using photographs.[2] From this early interest in the applications of photomechanical printing on a mass scale, to his experiments with photography as a documentary tool, from images of Buddhist sculptures in Nara, solar eclipses, and famous tourist attractions, to his widely circulated reproductions of photographs of two successive wars, Ogawa’s work argued in favor of photography as the most suitable medium through which to record and consume information about the world. His specific contributions to the history of photography and publishing in the late Meiji period (1869-1912) are recognized by Japanese art historians and curators as foundational, but because of the heterogeneous subjects he photographed and the variety of photographic projects he helped to publish, there has been little attempt to consider the importance of Ogawa’s overall oeuvre, both to the history of photography and to the history of photographic technology.

In this article, I argue against the inclination to categorize his photographic works as either “artistic,” “scientific,” “commercial” or otherwise. Instead, I combine the scholarly perspective of the history of technology, publishing, and art to consider the ways in which Ogawa’s many photographic activities in combination create a picture of contemporary attitudes toward the manifold possibilities of photography as an imaging technique. What mattered most to Ogawa was not whether photography was an art or a technology, but, rather, that it was a malleable medium that should be used in as many contexts as possible. Through a focus on the role he played in making it possible to cheaply mass reproduce photographs through the halftone process, I argue for Ogawa’s historical significance to our understanding of the many functions that photographs played in the press and the historical development of their increasing value as eyewitness documents during wartime.

![Fig. 2. Photographic Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. 31 x 45 cm., Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 2. Photographic Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. 31 x 45 cm., Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000002-ic.jpg) Fig. 2. Photographic Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. 31 x 45 cm., Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 2. Photographic Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. 31 x 45 cm., Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.At the turn of the twentieth century, Ogawa’s publishing company printed two key volumes in collaboration with the publishing house Hakubunkan: A Photographic Album of the Japan-China War (Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖), a single album that was printed in collotype from 1894-1895; and the Russo-Japanese War Album (Nichiro seneki shashinjō日露戦役写真帖), a series of albums printed in collotype and halftone from 1904—1905. This thirty-two volume series and its accompanying exhibition are compelling examples of the transition in printing technology from collotype to halftone and reveal much about the excitement around photography as a technology to communicate information about war. They are also a record of perceptions of the visual challenges photographic technology posed in the very moment that it was beginning to build momentum in the mass press in Japan. Through his unwavering efforts to profit from the business of selling photographs, it was the mass-produced halftone, not the individual print, and the publisher, rather than the photographer who made photographic history.

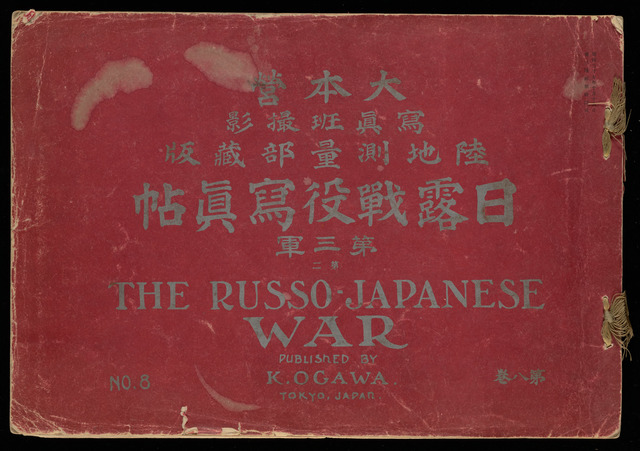

Fig. 3. The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photography Department of the Imperial Headquarters. No. 8. (Nichiro seneki shashinjō 日露戦役写真帖 陸地測量部藏版 第八巻) Tokyo: K. Ogawa, 1904. 27 x 38 cm. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 3. The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photography Department of the Imperial Headquarters. No. 8. (Nichiro seneki shashinjō 日露戦役写真帖 陸地測量部藏版 第八巻) Tokyo: K. Ogawa, 1904. 27 x 38 cm. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.Examining a range of Ogawa’s photographic activities demonstrates that his life’s work was not dedicated solely to establishing a place for photography first and foremost as an art form. Although he certainly had a stake in this discussion, as an entrepreneurial publisher it benefitted him most for viewers to see photography as a form of entertainment and information that consumers of print media could participate in. Similarly, it benefits current-day historians not to categorize his commercial works as somehow inherently different from his photographs of national treasures, which have been elevated to the status of “art” in exhibitions such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Photography Museum’s Image and Essence: A Genealogy of Japanese Photographers’ Views of National Treasures, held in 2000. Okatsuka Akiko, the curator who brought to light many of Ogawa’s unknown and varied works, has also canonized him as the progenitor of Japanese art appreciation and the Meiji period’s leading advocate of photography’s primary use as an art form. Okatsuka proposes the idea that Ogawa’s lighting and framing of Buddhist statuary was “the first time in Japan, that a fixed art object was being visually appreciated as such. To put it more boldly, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that Japanese art history has been visually formed by Ogawa’s photographs.”[3]

Although I agree that Ogawa left a mark on Japanese art history, I put forth a different explanation of Ogawa’s contributions here. He certainly contributed to the way that bijutsu (art) was defined in relation to Euro-American conceptions of art and exhibition practices, however his most significant contribution was to make photography the primary medium through which people would see the world on the printed page.

Ogawa Kazumasa and the History of Photomechanical Reproduction in Japan

Ogawa, like the practice of photography, constantly changed and folded new technologies into his daily work. If, as Anne Marsh argues in Contemporary Photography Since 1980, photography’s value is in its border crossing, Ogawa’s truly cross-disciplinary approach to employing new forms of photomechanical reproduction is an exemplary case in the history of photography.[4] A brief summary of Ogawa’s education and key professional activities illuminates his efforts to turn his knowledge of photographic technology into a highly decorated career.

Born in 1860 in the Oshi domain (current day Saitama Prefecture), to a samurai family of the Matsudaira daimyo, Ogawa moved to Tokyo in 1873 to study at the Arima School where a missionary teacher introduced him to photography. [5] In 1875, Ogawa became the apprentice to Yoshiwara Hideo, whose image of an erupting Mt. Bandai would become the first photograph to be printed in a Japanese newspaper a little more than ten years later.[6] In 1877, he opened his first photography studio in the silk-factory town of Tomioka, Gunma Prefecture. Ogawa closed shop in 1880 and two years later moved to Yokohama, where he became an English interpreter. Soon after, he boarded the American ship Swatara as one of the crew members in payment for his passage to the United States, and spent the next year and a half conducting a survey of the latest technology in photo-mechanical reproduction.

In Boston, Ogawa studied collotype printing and portraiture with the Ritz & Hastings Company before moving on to study with the Albert Type Company, whose factory he visited daily. Ogawa then moved to Philadelphia and there studied dry-plate manufacturing with John Carbutt, the very person who had pioneered the technology and who in 1888 developed the celluloid film technology that lead to the birth of cinema.

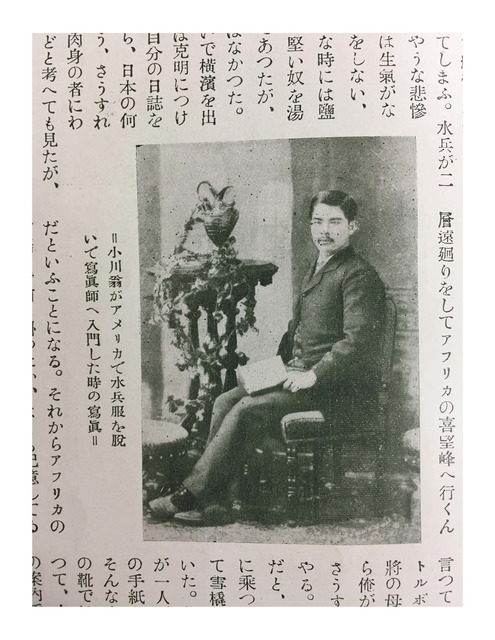

Fig. 4. “A Photograph of the Venerable Ogawa, who having shed his sailor’s clothes became a student of photography in America,” in “Ogawa Kazumasa ō: keirekidan. Shashin-shi” (The Honorable Ogawa Kazumasa: A Personal History of Photography) Asahi Camera. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, November 1927: 529.

Fig. 4. “A Photograph of the Venerable Ogawa, who having shed his sailor’s clothes became a student of photography in America,” in “Ogawa Kazumasa ō: keirekidan. Shashin-shi” (The Honorable Ogawa Kazumasa: A Personal History of Photography) Asahi Camera. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, November 1927: 529.Upon Ogawa’s return to Japan in 1885, he established a studio — the Gyokujunkan (玉潤館) — explicitly for portrait photography, and in 1889 he opened the first Japanese facility for mechanically reproducing photographs, the Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Copperplate Engraving Studio (Ogawa Kazumasa Shashin Seihanjō or Ogawa Kazumasa shashin chōkoku dōbanjō). Soon after, the Army General Staff Office appointed him chief photography instructor, a position that would lead to lucrative photographic reproduction deals with the army during the Sino- and Russo-Japanese wars of the next two decades. In 1887, Ogawa was appointed the official photographer for the American Eclipse Expedition led by D.P. Todd, which would study a solar eclipse at Shirakawa, Japan, where he met W.K. Burton. He played a similar role as the official photographer to the 1888 Kinai Survey: two trips led alternatively by Kuki Ryūichi and Ernest Fenollosa to document valuable statues, paintings, and other historic objects held by temples, shrines, and private collections, which later were classified as “national treasures.”[7]

Until this photographic excursion, Ogawa printed photographs taken by himself and other photographers in collotype, a method of mechanical reproduction using gelatin-coated plates that beautifully duplicates the tones of a photograph but is costly to produce and only possible in limited edition.[8] Ogawa advertised the collotype reproductions of photographs as single images or collections sold as albums through newspaper publicity and exhibitions of the original photographs. For example, in 1891, in a move that capitalized on a long history of the commodification of bijinga (pictures of beautiful women, most often geisha) in combination with the recent interest in staged portraits of so-called Japanese customs for the foreign tourism market, he exhibited 100 portraits of geisha from around Tokyo to celebrate the Ryounkaku, a twelve-story tower that was at the time the tallest building in Tokyo.[9] Ogawa invited viewers at the exhibition to vote on their favorite portrait and the winning subject received a prize. In this brilliant publicity move, the game of voting for one’s favorite beauty enticed viewers of the exhibition to buy the collotype album, “Types of Japan, Celebrated Geysha [sic] of Tokyo and From Photographic Negatives Taken by Him,” in which the photographs from the exhibition were reproduced.[10] This is one of the first instances when Ogawa encouraged customers to think of a reproduction of a photograph as having a direct connection not only to the original photograph, but to the very scene of the taking of the photograph itself. By voting for their favorite geisha’s photographic image, viewers participated in giving a real person a prize; by buying the album of a collection of beauties, customers brought themselves closer to the moment when these women posed in Ogawa’s photographic studio for their portraits. For the next fifteen years Ogawa continued to capitalize on the spectacle of public exhibitions and viewers’ desire for closeness to the original scene, though in the mid-1890s he began to concentrate on newspapers as a much more powerful advertising technique.

The real turning point of Ogawa’s career was his introduction of the halftone printing process to Japan. In 1893, Ogawa traveled as the Japanese representative to the Congress of Photographers at the Chicago World’s Fair. It was during this five-month trip that he learned about the latest developments in halftone reproduction, a technique that the Getty Conservation Institute describes as “not a single, well-defined photomechanical printings process” but two processes: “The first translates continuous tonalities of photographic prints of negatives into a series of dots. The second uses different methods of mechanical printing to produce a print that simulates the continuous tonality of reproduced photographs.”[11]

This new method of printing made it possible to reproduce photographs on lower quality paper in much higher print numbers than ever before, thus making it possible to fill newspapers and cheaply produced magazines with photographs. The Tokyo Asahi Shinbun reported on February 15, 1894, that Ogawa purchased the necessary equipment to produce halftone images in the United States and brought them back with him to Tokyo.[12] Over the next decade, Ogawa skillfully aligned his name with the halftone process to the extent that if it was a halftone, it was likely that Ogawa was behind it.

The Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) Through the Halftone Photograph

Two wars at the turn of the twentieth century defined the way that new visual technologies could be used to visualize combat. Just a decade apart, the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5) were often described by contemporary journalists in terms of superlatives: the most recorded wars in history depicted through the widest variety of imaging techniques, the largest land battle, the greatest amount of international commentary in the foreign press.[13] These accounts of the media frenzy around these wars illustrates how quickly visual media were changing and the importance of spectacle to modern viewers.

Both wars were depicted through photographs, woodblock prints, and lithographs. They were also reproduced on clothing, in albums, newspapers and commemorative postcards. This wide variety of images gave viewers around the world access to information, entertained them, and also produced what art historian Gennifer Weisenfeld calls an “intermedia dialogue” between different formats of images printed in a variety of mediums and periodicals.[14] In addition, within the conversations that were formed between hand drawn lithographs and photographs, for example, the increasing interest in the photographic image’s capacity to document events slowly turned it into the source around which all new visual information revolved. In newspapers, magazines, and photographic albums, the “purported verisimilitude of the photodocumentary” was the reference point for building a narrative of the event, “but it revealed the inadequacy of any one medium, including the ‘realistic’ mode of photography, to express the totality” of the war.[15] As I will discuss later in this paper, Ogawa succeeded in finding ways to market photographs as the most immediate means of accessing information about the wars – from battle scenes depicting triumphant Japanese soldiers to the banality of waiting in between battles – at the same time conceding the technical limitation of the medium by providing hand drawn or engraved supplements to the photographs that filled in missing information.

Despite the many challenges that the contemporary state of photographic technology posed to mass reproduction in the late twentieth century, newspapers around the world seized the opportunity to use the halftone process to bring photographic images to readers who had grown an insatiable appetite for more expedient access to the world.[16] The first photographic image in a newspaper was printed on December 2, 1873 in the New York Daily Graphic; on April 4th, 1880, the same paper printed the first halftone photograph. “A Scene in Shantytown, New York: Reproduction Direct from Nature,” taken by Stephen Henry Horgan was described in its accompanying article as the “first reproduction of a photograph with full tonal range in a newspaper.” The immediate excitement over the halftone process and belief that it provided a better version of photographs to newspaper readers reflects historians Gerry Beegan and Jason E. Hill’s discussions of how the halftone process fed the simultaneous desires for direct copies of a photograph unmarred by the hand of the engraver and the demand for immediacy in news reporting.[17]

At this time the newspaper industry in Japan had gone through a major transition: it moved from close ties to the newly established government to focusing more on the needs of a growing reading public.[18] In the 1870s, there were primarily two types of newspapers: the ōshinbun (literally, “large newspapers”), which were written in a complex prose style and aimed at a highly educated audience, and the koshinbun (“small newspapers”), which beginning in the 1880s targeted women and children by including pictures and utilizing a more accessible writing style. If, as historian James L. Huffman contends, the newspaper played a large role in transforming its readers from subjects into citizens in late-nineteenth century Japan, then the photographs that they printed played a large part in this shift as readers of the illustrated press were connected through a new kind of photographic literacy.[19]

The first photograph to be mechanically reproduced in a Japanese newspaper was an image of the volcano Mt. Bandai, in Fukushima Prefecture, as it erupted. The Yomiuri Shinbun dispatched the photographer Yoshihara Hideo, with whom Ogawa had apprenticed, and his scene of the volcanic explosion was printed using asphalt copperplate on August 5 and 7 of 1888.[20] Over the following two months, this photograph was reproduced over thirty times in the Yomiuri, but the poor quality of the photogravure method used to print it meant that the fine tones of the original photograph were lost. To make up for its illegibility it was often accompanied by a woodblock print in which the eruption was much more vibrantly rendered. This illustrates that from the debut of photographic images in the mass press they existed in conversation and translation with other forms of visual media.

It was with Ogawa’s assistance that on June 16, 1894, the Asahi Shinbun published its first photographs using the halftone printing process in four images (a landscape of the Korean capital, a photograph of a Korean warship, and two of Korean military officials) to acknowledge the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War.[21] Up to that point, photographs in Japanese newspapers were few and far between, but the halftone process made possible for the first time multiple-image, full-page photographic layouts as well as the inclusion of text with a photographic image on the same plate. What is also significant about these photographs is that starting with the single-page insert of scenes of the Japanese military and the Great Wall field headquarters published in the July 24th issue of the Asahi Shinbun, the name of Ogawa’s press was printed next to the image on the newspaper page. In this way, both the newspaper and Ogawa benefitted from the advent of photographs in its pages: while feeding the public demand for photographic images, Ogawa was able to place free advertising for his services in the hands of thousands of readers. It was thus through the halftone that Ogawa reached wider audiences than ever before and left a mark on the way that photography was used in the mass press.

The explicit promotion of his work would have enticed readers who wanted to see or own more than the handful of photographs printed in the newspaper to buy the Nisshin Sensō Shashin-zu (A Photographic Album of the Japan-China War) which was sold beginning in October 1894 and could be purchased as a full album or as individual collotype or halftone sheets.[22]

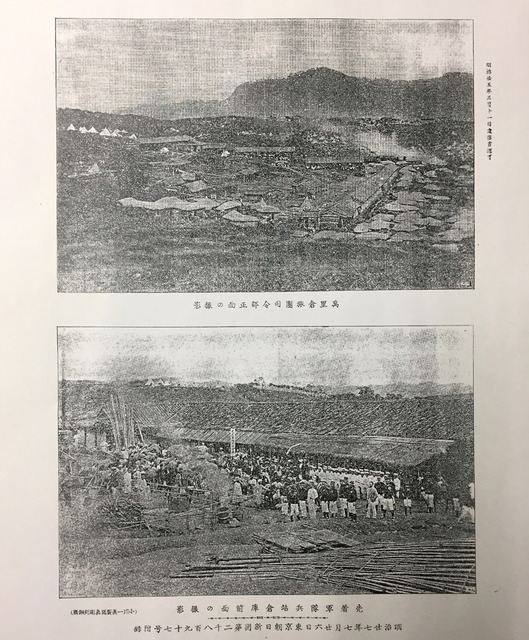

Fig. 5. “Report by the Permission of the Ministry: In Front of the Great Wall Field Headquarters Warehouse” and “In Front of the Military Warehouse” (Tsūshin shōninka). Tokyo Asahi Shinbun Supplement July 24, 1894.

Fig. 5. “Report by the Permission of the Ministry: In Front of the Great Wall Field Headquarters Warehouse” and “In Front of the Military Warehouse” (Tsūshin shōninka). Tokyo Asahi Shinbun Supplement July 24, 1894.  Fig. 5a. Detail of credit given to Ogawa’s press for providing halftone printing services to the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, from bottom left of the insert. “The Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Copperplate Engraving Studio” (Ogawa Kazumasa sei shashin chōkoku dōban), Tokyo Asahi Shinbun Supplement July 24, 1894.

Fig. 5a. Detail of credit given to Ogawa’s press for providing halftone printing services to the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, from bottom left of the insert. “The Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Copperplate Engraving Studio” (Ogawa Kazumasa sei shashin chōkoku dōban), Tokyo Asahi Shinbun Supplement July 24, 1894.The lavishly illustrated album was printed in eight different volumes and contained a mixture of black and white collotypes, lithographs, and maps. From December 1894 to January 1896, Ogawa’s press published the photographic album, Chronicle of the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin Sensō Jikki), three times a month in partnership with the publisher Hakubunkan. This cheaply produced periodical, printed mostly in black and white, combined woodblock prints with halftone photographs and short vignettes from the battlefront. Advertisements for it, such as the one pictured below, enticed readers with long lists of scenes of battle, portraits of politicians and military men, and color photographs included in each new volume. At a time when photographs were just beginning to be printed in newspapers, special periodicals such as this were in high demand. In the context of war, reproducing photographs became very profitable for Ogawa.

Fig. 6. Advertisement for the Chronicle of the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin Sensō Jikki): “Portraits of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean Politicians Against Portraits of Naval Officers and Warships. Insert Color Photographic Engravings of China and Korea. The Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Studio.” Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, August 31, 1894.

Fig. 6. Advertisement for the Chronicle of the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin Sensō Jikki): “Portraits of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean Politicians Against Portraits of Naval Officers and Warships. Insert Color Photographic Engravings of China and Korea. The Ogawa Kazumasa Photographic Studio.” Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, August 31, 1894.At the very moment when newspapers were beginning to use photographic images as a draw for their readers, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters signaled interest in the importance of photography as a documentary practice by establishing the Imperial Photography Unit in 1894.[23] On September 21 of that year, the unit was dispatched to the Korean peninsula; it returned in May 1895. Ogawa had served occasionally as the official photography instructor to the Imperial Army since his return from the United States, in 1884, and was perfectly positioned to facilitate the reproduction and publication of the Imperial Photography Unit’s photographs in the Photographic Album of the Japan-China War (Nisshin Sensō Shashin-zu) albums.

From August 5 to 7, 1895, the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, reporting on the events of a reception held by the Japan Photography Association, described what an immense challenge it was for the Imperial Photography Unit to take photographs on the battle field.[24] The chief of the unit recounted to those present that commanding officers had no understanding of the mechanism or importance of photography and therefore did not allow the photographers to accompany the main troops. Instead, they were left to follow in the wake of a battle, and because most military operations took place before dawn, the lighting conditions made it almost impossible to take a picture. What is more, the difficulty of transporting heavy equipment and challenges to photographing any sort of motion made the idea of capturing a battle in action close to impossible.

Picturing Conflict: Filling in for Photographic Absence

The challenges described by the chief of the Imperial Photography Unit help explain the composition and lack of clarity in many of the Photographic Album of the Japan-China War album’s photographs: in them one can see a captivating example of how still landscape images were in great need of translation or illumination by an album’s accompanying action-packed lithographs, which together became the sites of dynamic action.[25]

The Sino-Japanese War began as a Japanese attempt to assert dominance in Asia as well as gain international recognition as an imperial power, and to that end set many international records for modern warfare: the Battle for Port Arthur, Manchuria, was the largest battle in world history to date, in which as many as sixty thousand people may have been killed, and the war ended in what the historian John Dower characterizes as China’s “shattering defeat.”[26] As the historian Frederic A. Sharf writes, the siege of Port Arthur itself “required six months of slow, bloody, and tedious effort that was costly not only in monetary terms but even more so in the loss of human lives on both sides . . .[and] the entire process took place in a relatively confined geographic area.”[27]

![Fig. 7. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Explosion and Burning of the Powder-Magazine on the Sungshoo Forts, Port Arthur”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894–95. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 7. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Explosion and Burning of the Powder-Magazine on the Sungshoo Forts, Port Arthur”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894–95. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000008-ic.jpg) Fig. 7. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Explosion and Burning of the Powder-Magazine on the Sungshoo Forts, Port Arthur”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894–95. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 7. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Explosion and Burning of the Powder-Magazine on the Sungshoo Forts, Port Arthur”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894–95. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.Figures 7—11 are part of a ten-photograph series and all bear the title, “The Fall of Port Arthur.” Though there are other photographs in this album that depict staged group gatherings and fortresses, these images demand the highest amount of imagination from the viewer and stand in greatest contrast to the scenes that they are chosen to describe. In their plain, empty, and almost deserted content, they clearly communicate the tedious process of the siege and bear more resemblance to the visual tropes of geographical and geological survey photographs than what one might expect from the documentation of a battle.[28] Some, such as figure 7, are accompanied by more detailed subtitles that add a narrative description to the image. This photograph in particular relies on its accompanying text to convey information; without it, the viewer would be lost in a creative reading of what may or may not be taking place in the seemingly empty black hills. The full text reads:

“The black smoke on the mountain on the left shows the fire in the forts. The fort on the summit to its right is also one of the Sungshoo forts. The two peaks on the right of the same range are the Urlung forts. The figures on the summit at the centre of the range are troops, and the buildings over which a mast stands are the left barracks of the van on the E-tse troops. The high peak above it is the watch-tower of the Urlung Mountain. Taken on the 21st November, 1894.”

With this description, the viewer can begin to pick out small specks of detail in the hills, but without a magnifying glass one could not be too sure where the supposed figures in the center or on the summit are.

Figure 8 is a display of similar poetic mystery, or perhaps the caption describes what was once there but is no longer: Chinese troops and flags that the caption refers to are nowhere to be seen, leading one to wonder if this image is perhaps a memorial of the event rather than an actual depiction of it. Alternatively, the smoke muddying the photograph could also be lingering from the battle long ended. It is possible that figure 9, “The Fall of Port Arthur: The First Infantry Regiment Fighting Near Fongheatun, W. of Port Arthur. Taken on the 21st November, 1894,” could be a photograph taken mid-battle, but the smoke that shrouds the far valley obscures the conflict.

![Fig. 8. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Rally of the Chinese Troops who had been routed by the Frist Infantry Regiment Near Fongheatun, W. of Fort Arthur. The character on the fourth and fifth flags from the right is (Li). Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 8. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Rally of the Chinese Troops who had been routed by the Frist Infantry Regiment Near Fongheatun, W. of Fort Arthur. The character on the fourth and fifth flags from the right is (Li). Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000009-ic.jpg) Fig. 8. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Rally of the Chinese Troops who had been routed by the Frist Infantry Regiment Near Fongheatun, W. of Fort Arthur. The character on the fourth and fifth flags from the right is (Li). Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 8. “The Fall of Port Arthur: Rally of the Chinese Troops who had been routed by the Frist Infantry Regiment Near Fongheatun, W. of Fort Arthur. The character on the fourth and fifth flags from the right is (Li). Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.![Fig. 9. “The Fall of Port Arthur: The First Infantry Regiment Fighting Near Fongheatun, W. of Port Arthur. Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 9. “The Fall of Port Arthur: The First Infantry Regiment Fighting Near Fongheatun, W. of Port Arthur. Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000010-ic.jpg) Fig. 9. “The Fall of Port Arthur: The First Infantry Regiment Fighting Near Fongheatun, W. of Port Arthur. Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 9. “The Fall of Port Arthur: The First Infantry Regiment Fighting Near Fongheatun, W. of Port Arthur. Taken on the 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894—1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.More akin to aerial surveys of the aftermath of recent battles, these photographs are mysterious, almost surreal images of an invisible war. Though they are practically nonsensical in the lack of information they provide, as the first photographs that a wide Japanese audience saw of the step-by-step process of modern warfare, these images would have stimulated the curiosity and imagination of their viewers. The “Supplement” section of the album rescues the viewer from the tedium of the photographs and provides a Japanese audience familiar with nishiki-e woodblock-print dramatizations of battle scenes with more spectacular action.

The final twenty pages or so of the album is comprised of a collection of lithographs (they could also be paintings that have been photographically reproduced) that show the battles at their height.[29] Each of the lithographs, like the photographs in the albums, bears the name, “Ogawa Kazumasa Shashinban” (The Ogawa Kazumasa Photogravure Studio) printed vertically next to it. In the supplement section, there is a drawn illustration for almost every major battle photographed in the album, suggesting that they were meant to be read together as a full illustration of the war. The hazy, cloudy background and hilly terrain of the battle in figure 10, “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Japanese Infantry Storming the Etse Hill Forts. 21st November, 1894,” hints at the faint smoky hills in the photograph of figure 8. Uniformed men storm the hills, sabers and guns raised into the air, and even the fallen seem as though they are struggling forward to join the battle. Figure 11, titled “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Infantry of General Hasegawa combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1884” draws attention to the brutality of the war. In the foreground, men are locked in hand-to-hand combat, and on the upper left-hand side of the image a Japanese solider stabs a Chinese man in the back. In this image and others, the Chinese combatants can be identified through their stereotypical rendering as disorganized figures in loose clothing, bare foreheads, and long queues hanging down their backs, whereas the Japanese are consistently shown in military uniforms, marching in formation.

![Fig. 10. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Japanese Infantry Storming the Etse Hill Forts. 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 10. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Japanese Infantry Storming the Etse Hill Forts. 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000011-ic.jpg) Fig. 10. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Japanese Infantry Storming the Etse Hill Forts. 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 10. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Japanese Infantry Storming the Etse Hill Forts. 21st November, 1894”, A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.![Fig. 11. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Infantry of General Hasegawa combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984.” A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. Fig. 11. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Infantry of General Hasegawa combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984.” A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0007.201-00000012-ic.jpg) Fig. 11. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Infantry of General Hasegawa combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984.” A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 11. “Supplement. The Fall of Port Arthur. The Infantry of General Hasegawa combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984.” A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894-1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.Like the nishiki-e, woodblock prints that were made available for mass audiences during the same period, these lithographs expressed sentiments of “nationalism, militarism, imperialism, [and] a new sense of cultural and even racial identity.”[30] Even still, their drama and emotion hinge upon their relationship to the photographs in the album. It is as if the photographs say, “We were there and this really happened on a particular day,” and the lithographs follow up with an anecdotal flourish to embellish how events came to pass. In this way, the different pictorial strategies of the two highlight this moment of transition in the Japanese mass press from the engraver or lithographer’s hand to the eye of the on-site photographer.

In addition, the pairing of photograph and lithograph or lithograph and text provides a historical understanding of the visual response to the spectacle of war, and the relationship of one medium to the other troubles the notion of veracity. Both mediums are utilized to illustrate different versions of the “truth” that Ogawa seeks to communicate to the reader, be it the photograph’s testimony to the physical presence of the photographer on site or the lithograph’s communication of the drama of war. Yet this album puts forth the idea that seeing, or experiencing, an event photographically was of primary importance. Interestingly, whereas the English titles state only the location and name of the actors involved in the image, such as “The Infantry of General Hasegawa Combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984,” the Japanese title inserts the word shinkei (true view) to read “True view of the Infantry of General Hasegawa Combined Brigade Storming the Urlung Hill Forts. 21st November, 1984.”

The use of the term shinkei to describe these lithographs places them within a history of landscape painting that began in the late eighteenth century with works by the painter Ike Taiga (1723-1776). As the art historian Melinda Takeuchi shows, the word shinkeizu (true-view picture) was first used to describe Taiga’s landscape painting Mount Asama. In relationship to his works, it was argued that in order for “a picture (zu 図) of a given scene (kei 景) to be profound . . . the artist must experience the vista at first hand and absorb and transmit its essential reality (shin 真).”[31] Ewa Machotka emphasizes the interpretive role of the artist in rendering shin in this context: “The picture in this format was not supposed to give a realistic description of a certain locality, but rather to be based on the personal feeling and understanding of the place by a particular artist.”[32]

Maki Fukuoka’s compelling research on the origin and evolution of the term shashin, which literally means “representation of the real” (and carries within it the same character, shin) but later comes to mean “photograph,” adds another layer of meaning to the interaction between the photograph and hand-drawn image.[33] In its early uses up to the nineteenth century, the term shashin came to represent the process by which the producer of an image had come into physical contact with the object depicted. From rubbings of plants used by natural scientists, to copper etchings and texts, and eventually to photographs, the term shashin delineated the technologies of visualization that were the most capable of conveying verifiable information. Thus, the act of creating both a shashin and a shinkei was based on the empirical interpretation of the author. The art historian Satō Dōshin contends that by the mid—late nineteenth century, each was used in such a variety of ways its signification constantly wavered between the “double meanings of visual verisimilitude and the representation of inner truth.”[34] Although it is unknown whether the artists who drew the lithographs were present at these battle scenes, it is noteworthy that their captions seek to place them within the same associations of experiential interpretation, arguing that both photograph and lithograph in the Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War are representations of the real. Therefore this album is a record of the last moment before photographic representations of eyewitness presence won out over hand drawn representations of eyewitness events and details.

Photographs of the Russo-Japanese War in Albums and Exhibitions

The popularity of the Sino-Japanese War albums and the partnership that Ogawa had with the Imperial Photography Unit set a precedent for the ways in which photographs of war on the Asian continent were swiftly produced to transmit images of Japanese military prowess to domestic audiences. A decade later, at the start of the Russo-Japanese War, officials in the military may have had an increased appreciation for the practical uses of photography during wartime, and they appointed Ogawa as the head of the Imperial Photography Unit.[35] Little is known about whether he indeed saw the battlefield. However, in comparison with his work printing images of the Sino-Japanese War, the albums that Ogawa’s press produced of the Russo-Japanese War shed light on the way that halftone technology and the mass press ushered in a photographic way of seeing and reporting on current events.

From 1904 to 1906, the Ogawa Shashin Seihanjō printed thirty-two volumes of the Russo-Japanese War Album (Nichiro Sensō Shashinjō).[36] These volumes became available for purchase eight months after the war started, which, considering the time it took to travel by sea between the Korean peninsula and Tokyo and then print the images, is a relatively quick turn-around. Their print run continued until after the end of the war: the final albums included images of the triumphant return of the military marching through celebratory arches in the streets of Tokyo. The different volumes printed under this name have a variety of attributions: some specify copyright held by the Military Survey Department or the Imperial Photography Unit, others record the photographer Ichioka Tajiro as the copyright holder.[37] Except in the case of the albums that bear Ichioka’s name, the authors of the majority of the photographs reproduced in the albums are unknown members of the Imperial Photography Unit. Okatsuka Akiko postulates that the smaller portion of albums that were printed in the expensive collotype process might have been done so on commission by the Imperial Headquarters, and would have been intended for members of the military.[38]

In the preface to the first volume, released in October 1904, Ogawa put forth a statement lauding the value of photographs as testimonial documents of visual precision. He wrote:

“Our Imperial Headquarters, impelled by the same consideration, resolved to obtain such faithful pictures of all the actions, movements, and for this purpose, as is doubtless well known to the public, attached photographic corps to the various armies in the field. And as these photographers carry on their work under the direction of the Imperial Headquarters, the views taken by them will, needless to say, deserve, on account of their range and accuracy, to be treasured as national memorials of permanent value.”[39]

Ogawa writes that the significance of these photographs derived in large part from the importance of the photographers as eyewitnesses to the incident. Later in the preface, he uses the term eyewitness reporting (mokugeki hōkōku) to describe the value of the images, revealing the assumption that these news images held what Vanessa Schwartz and Jason Hill call the illusive “promise to render a transparent account of the reported event.”[40]

Despite Ogawa’s praise for photography’s capacity to record events, the Russo-Japanese War album series is also testimony to the challenges that photographic technology still posed at the time. The assertive application of photographs in places where a diagram such as a map might have provided clearer information makes their use most interesting: the visual allure of the photograph was perceived as so important as to outweigh its visual shortcomings. For example, in volume 8, tracing paper has been glued to the top edge of the photograph “View of a Battle in the Direction of the First Division From a Hill South of Fenghuang Hill, 19th September, 1904, 4:20 pm.”[41] On the tracing paper, someone has carefully outlined the silhouette of the mountain ridges, labeled their names, and marked the names of encampments and battles that occurred in those mountains. Through the thin, transparent layer of paper lying on top of the photograph, the viewer can see the dark shadows and contours of the photographic image as it is modified by the hand drawn lines. By lifting the tissue paper, the viewer sees the bare photograph in which the far-flung hills are just barely discernable.

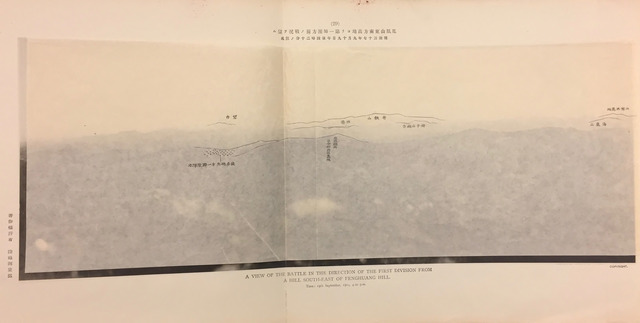

Fig. 12. “A View of the Battle in the Direction of the First Division From A Hill South-East of Fenghuang Hill, 19th September, 1904, 4:20 p.m.,” Photograph 29, from The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, photo by the author.

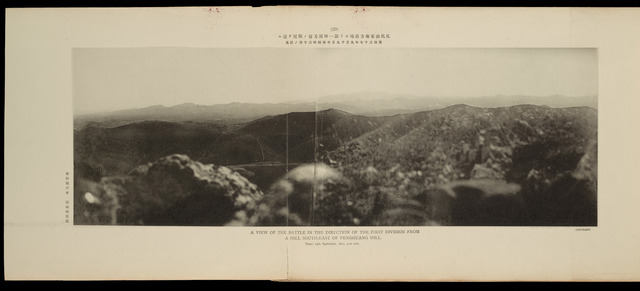

Fig. 12. “A View of the Battle in the Direction of the First Division From A Hill South-East of Fenghuang Hill, 19th September, 1904, 4:20 p.m.,” Photograph 29, from The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, photo by the author.  Fig. 13. “A View of the Battle in the Direction of the First Division From A Hill South-East of Fenghuang Hill, 19th September, 1904, 4:20 p.m.,” Photograph 29, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 13. “A View of the Battle in the Direction of the First Division From A Hill South-East of Fenghuang Hill, 19th September, 1904, 4:20 p.m.,” Photograph 29, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. The rocks and mounds in the foreground take up almost a quarter of the image but are out of focus as the camera lens’ focal point is set in the distance. There is a sharp contrast between the blurred foreground and clear mountains: without the tracing paper as a guide to the important details of the photograph, the viewer might struggle to pick out the encampment in the distance or understand what exactly he or she is looking at.

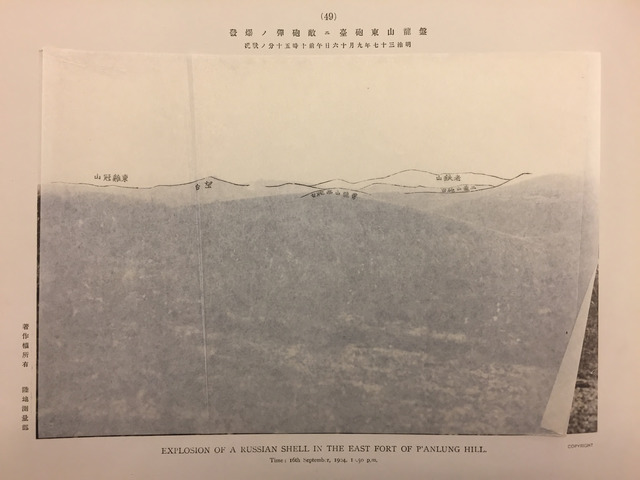

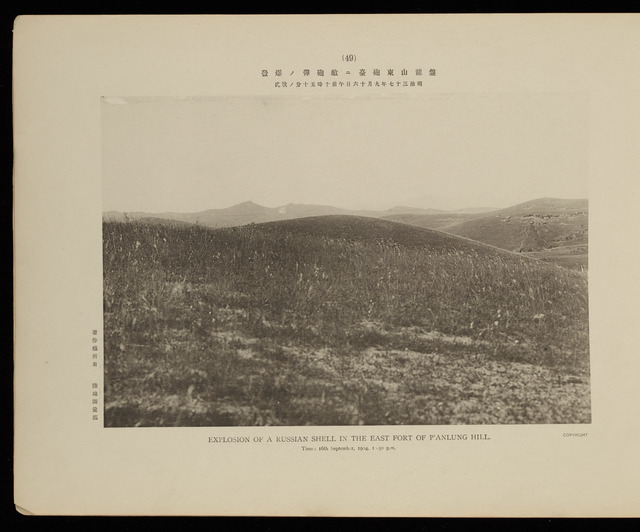

A second photograph, number forty-nine in the album, also relies on a transparent paper supplement as an information overlay. “Explosion of a Russian Shell in the East Fort of P’anlung Hill, Time: 16th September, 1904, 10:50 p.m.” shows an out-of-focus trodden, grassy hillside in the foreground. In the very far distance, to the left of the center of the horizon, one can just barely make out what might be the puff of smoke from an exploding shell. The tracing paper details of this image also outline encampments and mountain names, adding information to the photograph that must be read interactively by moving between tracing-paper and photograph. In an attempt to claim scientific precision, the carefully written tissue-paper labels paired with the assertive exactitude of the title connect the making of the image with a specific time as well as the location.

Fig. 14. “Explosion of a Russian Shell in the East Fort of P’anlung Hill, Time: 16th September, 1904, 10:50 p.m.” Photograph 49, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Photo by the author.

Fig. 14. “Explosion of a Russian Shell in the East Fort of P’anlung Hill, Time: 16th September, 1904, 10:50 p.m.” Photograph 49, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Photo by the author.  Fig. 15. “Explosion of a Russian Shell in the East Fort of P’anlung Hill, Time: 16th September, 1904, 10:50 p.m.” Photograph 49, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive.

Fig. 15. “Explosion of a Russian Shell in the East Fort of P’anlung Hill, Time: 16th September, 1904, 10:50 p.m.” Photograph 49, The Russo-Japanese War: Taken by the Photographic Department of the Imperial Headquarters. 『日露戦争写真帖』No. 8. K. Ogawa, 1904. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. The association that turn-of-the century photographs had with the accuracy of an eyewitness presence was not always mediated by supplements such as lithographs or hand-drawn overlays to add more information. In several intriguing cases, paper was used to cover the photographs of the Russo-Japan War albums to remove their eye-witness testimony. The historian Inoue Yuko points out two cases in which surviving copies of the first volume of the album bear the evidence of how, rather than remove a photograph of dead Japanese soldiers, the entire photograph and caption were pasted over with a piece of thick, green paper by government censors.[42] Kyoto University’s copy of the album bears the traces of a curious viewer who has torn away the censor’s paper to reveal the scene of at least nine dead soldiers lying in disarray on a hill. This photograph is evidence of more than just the occurrence of battle; it also demonstrates the descriptions by the historians Tom Allbeson and Pippa Oldfield of how photographs themselves and “their circulation are part of the tools and practices of warfare.”[43]

As he did in the case of the exhibition of geisha portraits in 1891, in April 1905 Ogawa returned to the popular exhibition format to advertise his photographic albums. The Great Exhibition of Color Photographs of the Russo-Japanese Battle (Nichiro sen’eki saishiki dai shashin tenrankai) was held in an exhibition hall in Ueno Park and put on display one hundred photographs from the Imperial Army and twenty photographs from the Imperial Navy, many printed at the enormous dimensions of about three by five feet.[44] Displayed on this scale, the photographs dramatically delivered information about modern warfare to crowded audiences. The title of the exhibition and Ogawa’s name were painted in large lettering at the entrance to the hall, visible to all who passed by. Although these photographs were a means to advertise the exploits of Japanese imperialization — in color and on a grand scale — they were also endorsements for the many ways in which photography could be used to depict an event. In addition to their relevance to the history of photographic technology, these images, and the process by which thousands of viewers saw them, speak to the level of access and intimacy that audiences were able have with scenes of war, and are an important part of historical inquiry into the visual culture of war.

Fig. 16. “The Great Exhibition of Colored Photographs of the Russo-Japanese Battle” (Nichiro sen’eki saishiki dai shashin tenrankai), 1907. Hakodate Central City Library.

Fig. 16. “The Great Exhibition of Colored Photographs of the Russo-Japanese Battle” (Nichiro sen’eki saishiki dai shashin tenrankai), 1907. Hakodate Central City Library.Conclusion

By the 1928 printing of Asahi Camera’s final essay on Ogawa’s life history, the world in which photographs on the printed page had been so hard won was a distant memory. Established magazines such as The Sun (Taiyo, 1895—1928), Art News (Bijutsu Shinpō, 1902—1920), and The Photographic News (Shashin Shinpō, 1882—1940), along with a multitude of more recent photography magazines such as Kamera (1921—1956), Art Photography (Geijutsu Shashin, 1922—1940), and Photo Times (Fototaimusu, 1924—1941), extensively featured photographs as one of their main attractions.[45] By the 1930s, many of these magazines utilized the new rotogravure technique to create creative and eye-catching layouts with an ease that had not been possible using halftone plates. During World War II, the lavishly produced propaganda magazine NIPPON (1934—1944), made use of intertwined photographic collages and bold graphic design to advertise Japan’s colonial empire.[46] With each new method of photographic reproduction, magazines and newspapers grew increasingly visual and, as Andrés Mario Zervigón writes, created the modern aesthetic of the news wherein “the picture, or a number of them stacked in interesting ways, almost always provided the pole around which the larger assembly spun.”[47]

Newspapers and magazines were irresistible cultural producers, and in his vital role in bringing photographs to their pages, Ogawa initiated the soon commonplace act of consuming news through photographs. As printing techniques improved, advancements to film and camera equipment as embodied by the popularization of the 35mm camera, in the 1920s, also made it possible to capture scenes that turn-of-the-century photographers on the battlefront could only have dreamed of.[48] Through Ogawa’s story as told by the Asahi Camera, burgeoning photographers connected with the history of the rise of the Japanese photographic press and the meanings of depicting imperialism at a corresponding time of Japanese aggression in Asia.

Kelly Midori McCormick is a Fulbright Graduate Research Fellow at Tokyo University and Ph.D. Candidate in the History Department at the University of California Los Angeles where she is currently completing her dissertation on the construction of photographic culture in Japan from the 1930s to 1960s.

NOTES

I would like to express my deep thanks to Grace Ballor, Carrie Cushman, William Marotti, Nick Risteen, Maia Woolner and the anonymous readers for their invaluable comments on this work. I am also indebted to the Getty Special Collections, the Hakodate Central Library, and the Asahi Shinbun for permission to reproduce these images. Research for this article was supported by the U.S. Fulbright I.I.E. Program.

1 See Ozawa Kiyoshi, Shashinkai no senkaku — Ogawa Kazumasa no Shōgai. Tokyo: Nihon Kokusho Kankōkai, 1994; Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa ga tegaketa amimehan insatsu ni tsuite “Tokyo asahi shinbun o chūshin ni,” Tsukuba: Tsukuba University Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences. Isebu Publishing, November, 2011: 9199; Anne Wilkes Tucker, et al., The History of Japanese Photography, New Haven: Yale University Press in Association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003: 314–18; Karen Fraser, “Ogawa Kazumasa (1860–1929) — Japanese Photographer,” in Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, ed., John Hannavy. New York & London: Routledge, 2008: 1021–1022.

W. K. Burton, “The Difficulties that had to be Overcome in Former Times in the Land of the Rising Sun,” Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, Vol. 21, New York: E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., 1890: 181–85.

“Utsusareta Kokuhō — Nihon ni okeru bunkazai shashin no keifu,” (Image and Essence: A Genealogy of Japanese Photographers’ Views of National Treasures), Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2000: 151.

Anne Marsh. Look: Contemporary Photography Since 1980. Melbourne: MacMillan Art Publishing, 2011: 379.

Terry Bennett has written the most thorough biography of Ogawa’s life available in English. Terry Bennett, Photography in Japan 1853—1912. Tokyo and Rutland, Vt.: Tuttle Publishing, 2006. In Japanese, see: Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa insatsu ・hakkō ni yoru 『Nichiro sensō shashinjō 』『Nichiro seneki kaigun shashinjō 』ni tsuite,” Tokyo, Edo-Tokyo Museum Bulletin, Vol. 2, 2012: 86.

Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa ga tegaketa amimehan insatsu ni tsuite・Tokyo Asahi Shinbun o chūshin ni,” Tsukuba: Tsukuba University Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences Isebu Publishing, November, 2011: 91—99.

For further information on the position photography held in these surveys and subsequent definitions of “art,” see Murakado Noriko, “Meiji-ki no kobijutsu shashin: Kinai hōmotsu chōsa torishirabe o chūshin ni,” Bijustushi 153 (2002): 146–65. See also Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa no ‘Kinki hōmotsu chōsa shashin’ ni tsuite,” Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Kiyo. No. 2 (2000): 37–55; Oliver Krischer, “Ogawa Kazumasa no bunkazai shashin ni tsuite.” Tsukuba: Tsukuba University Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences Isebu Publishing, March, 2010: 11–20.

See Dusan C. Stulik and Art Kaplan, “Collotype,” in The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2013.

Ibid., Terry Bennett, Photography in Japan 1853–1912: 210–17. See also W. K. Burton, “The Difficulties that had to be Overcome in Former Times in the Land of the Rising Sun,” Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin. Vol. 21, New York: E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., 1890: 181–185.

Ogawa Kazumasa, “Types of Japan, Celebrated Geysha of Tokyo and From Photographic Negatives Taken by Him.” Tokyo: 1892. 11 ¾ x 16 in.

Dusan C. Stulik and Art Kaplan, Halftone: The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institution, 2013: 5.

Frederic A. Sharf, Anne Nishimura Morse, and Sebastian Dobson. A Much Recorded War, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2005: 2. Commentary on the escalating scale, impact, and production of twentieth-century wars too invoked these superlatives. The first war in which a large amount of amateur and semiprofessional photographers “freely photographed for a mass audience,” the Spanish Civil War has also been called “the most photogenic war anyone has ever seen.” See Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986: 1.

Gennifer Weisenfeld, Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012: 36.

For histories of photomechanical reproduction, see Gerry Beegan, The Mass Image: A Social History of Photomechanical Reproduction in Victorian London. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2008; Rachel A. Mustalish, “The Development of Photomechanical Printing Processes in the Late 19th Century,” Topics in Photographic Preservation, Vol. 7. 1997: 73–87; for a history of the medium of visual journalism, see Jason E. Hill and Vanessa R. Schwartz, Getting the Picture: The Visual Culture of the News. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Jason E. Hill, “Snap-Shot: After Bullet Hit Gaynor,” in Getting the Picture: The Visual Culture of the News. Jason E. Hill and Vanessa R. Schwartz, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015: 190–196.

On the history of the modern newspaper in Japan, see James L. Huffman, Creating a Public: People and Press in Meiji Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1997; Inoue Yuko, Nisshin Nichiro sensō to shashin hōdō—senba o kakeru shashinshitachi. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Bunkan, 2012.

For further information on the changing format of Japanese magazines in the late nineteenth century, and especially those also printed by Hakubunkan, see Mori, Kei, “Meijiki zasshi no insatsu hyōgen — hakubunkan no zasshigun tasū wo kakutoku suru tame no shin gijutsu no ōyō — 1,” Joshi Daigaku Bijutsu Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō No. 32, 2002: 3–14; Mori, Kei, “Meijiki zasshi no insatsu hyōgen — hakubunkan no zasshigun tasū wo kakutoku suru tame no shin gijutsu no ōyō — 2,” Joshi Daigaku Bijutsu Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō No. 33, 2003: 31–42.

Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa ga tegaketa amimehan insatsu ni tsuite”: 94.

On Ogawa’s relationship with the Asahi Shinbun, see Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa ga tegaketa amimehan insatsu ni tsuite,” Tokyo Asahi Shinbun o chūshin ni,” Tsukuba: Tsukuba University Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences Isebu Publishing, November 2011: 91–99.

A Photographic-Album of the Japan-China War [Nisshin Sensō shashin-zu日清 戰爭 寫眞圖], Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1894–1895. Getty Special Collections, Internet Archive. 31 x 45 cm.

This is not to say that the albums did not include more-detailed photographs, such as groups of soldiers or military encampments. However, I chose to focus on a selection of the many sparse images to illustrate the visual challenges that photographic technology faced during this time.

John Dower, “Throwing Off Asia II: Woodblock Prints of the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95),” MIT Visualizing Cultures. Accessed November 10, 2016. http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/throwing_off_asia_02/index.html

See Robin Kelsey, Archive Style: Photographs and Illustrations for U.S. Surveys, 1850–1890. University of California Press, 2007.

It is unclear what medium they are, and their authors are unknown. However, regardless of whether they are lithographs or paintings, in the form they are presented they are photographs of the originals.

Takeuchi Melinda, “‘True’ Views: Taiga’s Shinkeizu and the Evolution of Literati Painting Theory in Japan,” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1, 1989: 3.

Ewa Mchotka, Visual Genesis of Japanese National Identity: Hokusai’s Hyakunin Isshu. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2009: 194.

Maki Fukuoka, The Premise of Fidelity: Science, Visuality, and Representing the Real in Nineteenth-century Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012.

Satō Dōshin, Modern Japanese Art and the Meiji State: The Politics of Beauty. Trans., Hiroshi Nara. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2011: 238.

The number of copies of each volume that was printed is not known, but likely was in the thousands.

Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa insatsu・ hakkō ni yoru 『Nichiro sensō shashinjō 』『Nichiro seneki kaigun shashinjō 』ni tsuite,” Tokyo, Edo-Tokyo Museum Bulletin, Vol. 2, 2012.

Images with the tissue paper included are by the author. Interestingly, the photographs with accompanying tissue paper amendments were not considered significant enough to be photographed for inclusion in the Internet Archive.

Tom Allbeson and Pippa Oldfield, “War, Photography, Business: New Critical Histories,” Journal of War & Cultural Studies 9:2 (2016): 97.

Okatsuka Akiko, “Ogawa Kazumasa insatsu ・hakkō ni yoru 『Nichiro sensō shashinjō 』『Nichiro seneki kaigun shashinjō 』ni tsuite,” Tokyo, Edo-Tokyo Museum Bulletin, Vol. 2, 2012: 93.

“Ogawa Kazumasa ō: keirekidan. Shashin-shi” Asahi Kamera. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, July, 1928: 100.

See Shirayama Mari and Yoshio Hori, eds., Natori Yōnosuke to Nippon kōbō 1931–1945 [Natori Yōnosuke and Japan Studio 1931–1945], Tokyo: Iwanami Shōten, 2006.

Andrés Mario Zervigón, “Rotogravure and the Modern Aesthetic of News Reporting,” in Getting the Picture: The Visual Culture of the News. Jason E. Hill and Vanessa R. Schwartz, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015: 197–205.

On the rise of photojournalism in Japan, see Ishikawa Yasumasa, Hōdō Shashin no seishun jidai [The early years of photojournalism], Tokyo: Kodansha, 1991.